Introduction

Anxiety disorders are the most common group of mental disorders and are associated with enormous societal costs (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Ruscio, Shear and Wittchen2010; Craske and Stein, Reference Craske and Stein2016). Both ‘genetic’ and ‘non-genetic’ (i.e. environmental) variables (as well as their interaction) have been proposed as potential risk/protective factors for anxiety disorders (Craske et al., Reference Craske, Stein, Eley, Milad, Holmes, Rapee and Wittchen2017), although such a distinction may be somewhat artificial, given that many risk/protective factors include both genetic and non-genetic components. The evidence on risk/protective factors for anxiety disorders has been summarized in several systematic reviews and meta-analyses. However, findings are conflicting and there have been no previous attempts to summarize in a single report the strength of the evidence for the different potential risk/protective factors for each anxiety disorder or to assess possible biases in the literature.

We present the results of an umbrella review of risk/protective factors for the most common anxiety disorders. We will focus on specific phobia, social anxiety disorder (SAD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), panic disorder (PD), and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) – the latter having been classified as an anxiety disorder until the publication of the 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Umbrella reviews systematically collect and assess the existing evidence from individual studies included in systematic reviews and/or meta-analyses and have an increasing role in evidence-based health care and evidence-based assessments (Ioannidis, Reference Ioannidis2009; Fusar-Poli and Radua, Reference Fusar-Poli and Radua2018).

In the current absence of valid biomarkers or clear mechanistic explanations for most mental disorders (Kapur et al., Reference Kapur, Phillips and Insel2012), the identification of putative (and, at least for some, modifiable) risk/protective factors may lead to the development of more efficient risk prediction models, and may offer clues for prevention and treatment (Paulus, Reference Paulus2015; Moreno-Peral et al., Reference Moreno-Peral, Conejo-Cerón, Rubio-Valera, Fernández, Navas-Campaña, Rodríguez-Morejón, Motrico, Rigabert, De Dios Luna, Martín-Pérez, Rodríguez-Bayón, Ballesta-Rodríguez, Luciano and Bellón2017; Fusar-Poli et al., Reference Fusar-Poli, Hijazi, Stahl and Steyerberg2018). Our aim was to systematically assess the amount of evidence and the robustness of associations between potential risk/protective factors and each of the aforementioned disorders.

Methods

We conducted an umbrella review (Ioannidis, Reference Ioannidis2009; Fusar-Poli and Radua, Reference Fusar-Poli and Radua2018) to assess the relation between potential risk/protective factors and anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorders. We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al., Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman2009) and the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines (Stroup et al., Reference Stroup, Berlin, Morton, Olkin, Williamson, Rennie, Moher, Becker, Sipe and Thacker2000) (online Supplementary Tables S1 and S2). The study protocol was pre-registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; CRD42017060090).

Search strategy and eligibility criteria

We searched PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus from inception to April 30 2018 for systematic reviews and meta-analyses of observational studies examining associations between potential risk/protective factors (see below) separately for each disorder. The search strategy used the keywords ‘systematic review’ or ‘meta-analysis’ and each of the disorders of interest. We also hand searched the reference lists of all systematic reviews and meta-analysis reaching full-text review.

Eligibility criteria were: (1) a systematic review or meta-analysis of risk/protective factors for specific phobia, SAD, GAD, PD, or OCD as defined in any edition of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) manual or the DSM; (2) inclusion of a healthy comparison group; and (3) studies reporting sufficient data (or that were retrievable after contacting the authors) to perform the analyses. We did not apply any language restrictions in the selection of systematic reviews or meta-analyses.

Even though we had hoped to include molecular genetic studies in the umbrella review, we found that the literature for the disorders investigated is dominated by candidate gene studies, which are known to have low credibility. Such risk factor assessment should await thus the publication of large genome-wide studies (Ioannidis et al., Reference Ioannidis, Boffetta, Little, O'Brien, Uitterlinden, Vineis, Balding, Chokkalingam, Dolan, Flanders, Higgins, Mccarthy, McDermott, Page, Rebbeck, Seminara and Khoury2008). Moreover, different analytical methods and assessment criteria are required for umbrella reviews of genetic variables (Ioannidis et al., Reference Ioannidis, Boffetta, Little, O'Brien, Uitterlinden, Vineis, Balding, Chokkalingam, Dolan, Flanders, Higgins, Mccarthy, McDermott, Page, Rebbeck, Seminara and Khoury2008).

Although in some DSM classifications previous to DSM-5 ‘panic disorder’ and ‘panic disorder with agoraphobia’ have been classified separately, we included both in our ‘panic disorder’ category. However, we have analyzed them separately where a study reported separate factors for each of these categories. We also considered separation anxiety disorder and selective mutism (‘anxiety disorders’ in the DSM-5), but they were not included due to the lack of systematic reviews and meta-analyses (online Supplementary Figs S6 and S7). Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), grouped as an anxiety disorder until the publication of DSM-5, will be covered in a separate manuscript.

Further information about the search strategy and the eligibility criteria can be found in the online Supplementary material.

Risk/protective factor definition

We used the following definition of risk factor: ‘that characteristic, variable, or hazard preceding the outcome of interest that, if present for a given individual, makes it more likely that this individual, rather than someone selected from the general population, will develop a given disorder’ (Mrazek and Haggerty, Reference Mrazek and Haggerty1994; Kraemer et al., Reference Kraemer, Kazdin, Offord, Kessler, Jensen and Kupfer1997). Similarly, protective factors are those where risk is found to be decreased. We assessed both stable factors (e.g. sex), for which time precedence does not need to be established, and factors that are subject to change within-subject. For the latter, we required that the determination of the factor preceded the diagnosis of the outcome (i.e. the disorder) even if the information on the factor and the outcome was collected at the same time point (as in the case of cross-sectional studies). This rule ensured that there would be time precedence for the assessments of factors and outcomes, although factors may have existed even before their determination, and disorders may have also existed before their diagnosis. Furthermore, when the factor investigated was related to personality dimensions (e.g. neuroticism), we also required that personality was assessed before the disorder was diagnosed in order to avoid state-trait influences (Reich et al., Reference Reich, Noyes, Hirschfeld, Coryell and O'Gorman1987). The definitions for each factor were those given in the corresponding systematic review or meta-analysis.

Following previous work (Radua et al., Reference Radua, Ramella-Cravaro, Ioannidis, Reichenberg, Phiphopthatsanee, Amir, Yenn Thoo, Oliver, Davies, Morgan, McGuire, Murray and Fusar-Poli2018) we grouped factors into several descriptive categories: sociodemographic, psychopathology, parental psychopathology, personality dimensions, substance use, life events, perinatal complications, parental rearing styles/attachment, and others.

Data extraction and selection

We used a systematic approach to extract and select the data. First, we identified the factors assessed in each systematic review or meta-analysis. Second, two investigators independently checked that each individual article included in the systematic review or meta-analysis met the same eligibility criteria applied to the systematic review or meta-analysis. Third, two investigators independently extracted the following data (from the systematic review or meta-analysis or, in most cases, from the individual studies): first author and year of publication; number of cases and controls; measure and size of the risk and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs); specific variables depending on the measure of effect size; and whether the study was a prospective cohort. Specific variables depending on the measure of effect size were: number of cases and person-times in exposed and unexposed for incidence rate ratios (IRR), number of cases and total number of exposed and unexposed for risk ratios (RR), number of exposed and unexposed and cases and controls for odds ratios (OR), and means and standard deviations for cases and controls for standardized mean differences (SMD). Fourth, two investigators independently rated the quality of the systematic review or meta-analysis using the Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR; Shea et al., Reference Shea, Grimshaw, Wells, Boers, Andersson, Hamel, Porter, Tugwell, Moher and Bouter2007) tool, with substantial interrater agreement (both weighted Cohen's kappa and intraclass correlation = 0.71; see online Supplementary material). A third investigator reviewed the extracted data to check for inconsistencies, and disagreements were resolved by consensus. For further details on the data extraction, selection, and quality assessment, see the online Supplementary material.

Statistical analysis

We performed statistical analyses commonly used in standard meta-analyses. However, we did not use the statistics provided in the included systematic review or meta-analyses because there are differences across-studies in the methods employed and because some analyses are often not conducted (e.g. the test for an excess of significant findings).

We conducted a separate random-effects meta-analysis for each factor and disorder. The outcomes of the meta-analyses were the effect sizes with their CIs and p-values, and the statistics required to assess the level of evidence (see below). Depending on the factor, we used IRR, RR, OR, or SMD Hedges' g. For descriptive purposes, we also report OR equivalents (eOR) of IRR, RR, and Hedge's g (see Fusar-Poli and Radua (Reference Fusar-Poli and Radua2018) for additional details).

We assessed between-study heterogeneity by estimating the 95% prediction interval – which evaluates the uncertainty for the effect that would be expected in a new study addressing that same association – and the I 2 metric (Ioannidis et al., Reference Ioannidis, Patsopoulos and Evangelou2007). I 2 > 50% were considered to represent substantial heterogeneity (Higgings and Green, Reference Higgings and Green2009). We also assessed whether there was evidence of small-study effects with Egger tests (Egger et al., Reference Egger, Davey Smith, Schneider and Minder1997), where statistical significance would mean potential reporting or publication bias in the smaller studies. Finally, excess significance (a relative excess of statistically significant findings) was assessed with a binomial test that compared the observed v. the expected number of studies yielding statistically significant results (Radua et al., Reference Radua, Ramella-Cravaro, Ioannidis, Reichenberg, Phiphopthatsanee, Amir, Yenn Thoo, Oliver, Davies, Morgan, McGuire, Murray and Fusar-Poli2018).

The levels of evidence of the associations between each factor and disorder were classified into convincing (class I), highly suggestive (class II), suggestive (class III), or weak (class IV) (Fusar-Poli and Radua, Reference Fusar-Poli and Radua2018). Convincing evidence required a number of cases (n) >1000, a highly significant association (p < 10−6), I 2 < 50%, a statistically significant 95% prediction interval, and the absence of small-study effects and excess significance bias. Highly suggestive evidence also required n > 1000, a highly significant association (p < 10−6), and that the largest study had a statistically significant effect. Suggestive evidence required n > 1000 and p < 10−3. Weak evidence required no specific number of cases and p < 0.05. Furthermore, after collecting all the available evidence, we noticed that, with few exceptions, there were fewer than 1000 cases for most factors. Therefore, we also examined these criteria removing the requirement of n > 1000, so as to obtain a more fine-grained appraisal of the evidence. For associations with significant evidence (classes I–IV), we also conducted a sensitivity analysis by using only prospective cohort studies.

Results

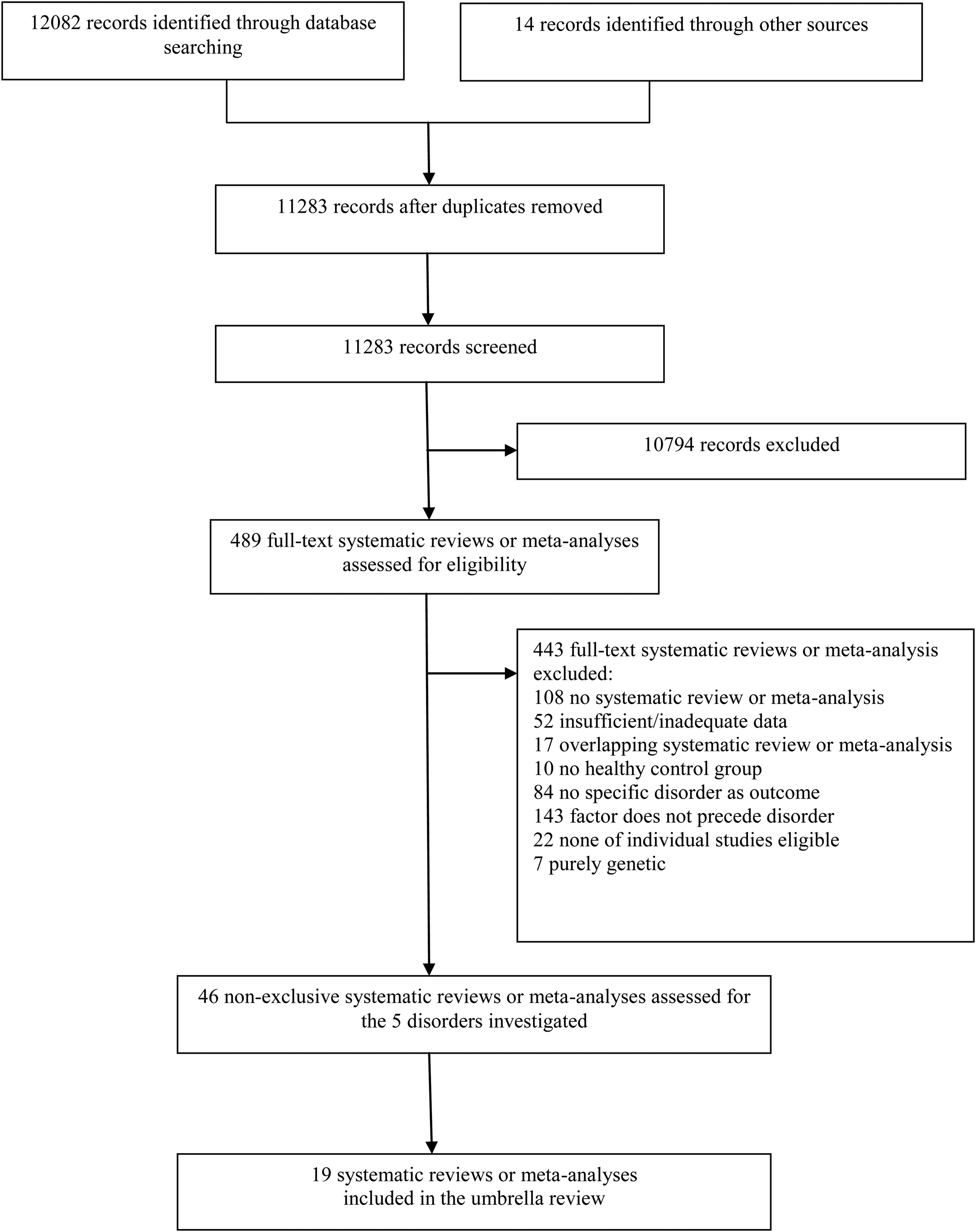

We included 19 systematic reviews and meta-analyses (Fig. 1 and online Supplementary Figs S1–S5). AMSTAR scores are presented in Table 1. All extracted data and results are available at: https://www.umbrellaevidence.com/anxiety/riskfactors/.

Fig. 1. Flow chart of the literature search (see online Supplementary material for the flowcharts for each specific disorder).

Table 1. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses included in the umbrella review, quality scores, and groups of risk/protective factors examined, by disorder

AMSTAR, Measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews; GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; PD, panic disorder; OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder; SAD, social anxiety disorder.

Note: Some risk/protective factors were assessed only for some of the disorders included in the corresponding systematic review/meta-analysis.

The specific risk/protective factors assessed in each systematic review or meta-analysis are reported in online Supplementary Table S4.

a Rounded-up average of two raters.

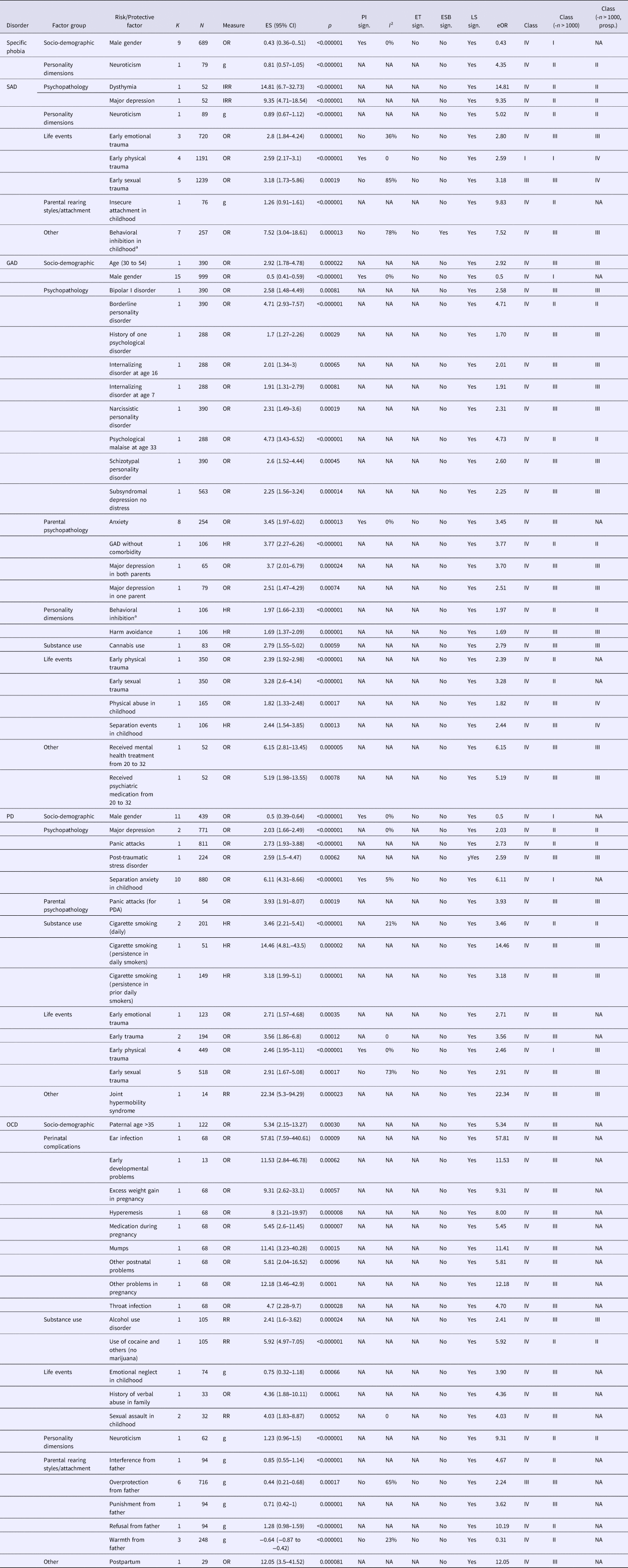

We extracted data for 427 factors from 216 individual studies. The number of systematic reviews and meta-analyses, individual studies assessed and included, and factors included are presented in Table 2. The groups of factors assessed in each systematic review or meta-analysis are reported in Table 1 and the specific factors in online Supplementary Table S3. Factors showing convincing, highly suggestive, or suggestive evidence of association with each disorder are presented in Table 3. All significant factors (including those showing weak evidence of association) are presented in online Supplementary Table S4.

Table 2. Number of systematic reviews and meta-analyses included in the umbrella review, individual studies assessed and included, and potential risk/protective factors included in the umbrella review, by disorder

Table 3. Risk/protective factors showing convincing (class I), highly suggestive (class II), or suggestive (class III) evidence of association with each disorder using the original umbrella review criteria or after removing the n > 1000 cases criterion, by disorder

Class, class of evidence, Class (−n > 1000)- class of evidence after removing the n > 1000 cases criterion, Class (−n > 1000, prosp.)– class of evidence after removing the n > 1000 cases criterion and after sensitivity analyses (including only prospective studies); CI, confidence interval; ES, effect size; ET, Egger test; eOR, equivalent odds ratio; ESB, excess significance bias; g, Hedge's g; GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; HR, hazard ratio; I 2, heterogeneity; IRR, incidence rate ratio; K, number of studies for each factor; LS, largest study with significant effect; N, number of cases; NA, not assessable; ns, not significant; OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder; OR, odds ratio; PD, panic disorder; PDA, panic disorder with agoraphobia; PI, prediction interval; SAD, social anxiety disorder; sign., significant; RR, relative risk.

a ‘Behavioral inhibition’ referred to ‘the chronic tendency to respond to novel persons, places, and objects with wariness or avoidant behaviours’ in one meta-analysis (Clauss and Blackford, Reference Clauss and Blackford2012) and to a personality/character dimension referring to ‘consistent restraint in response to social and non social situations’ in one systematic review (Moreno-Peral et al., Reference Moreno-Peral, Conejo-Cerón, Motrico, Rodríguez-Morejón, Fernández, García-Campayo, Roca, Serrano-Blanco, Rubio-Valera and Bellón2014).

Overall, the number of cases was greater than 1000 for 20 factors (4.68%). One-hundred eighty-three of the 427 factors (42.84%) presented a statistically significant effect (p < 0.05) under the random-effects model, but only 91 (21.31%) had a p < 0.005 and only 27 (6.32%) reached p < 10−6. Twenty-five factors (36.76%) presented a large estimate of heterogeneity (I 2 > 50%), while for 29 factors (78.37%) the 95% prediction interval did not include the null. Additionally, evidence for small-study effects and excess significance bias was noted for 2 (5.40%) and 8 (1.87%) factors, respectively (see online Supplementary Table S4).

Results by disorder

Specific phobia

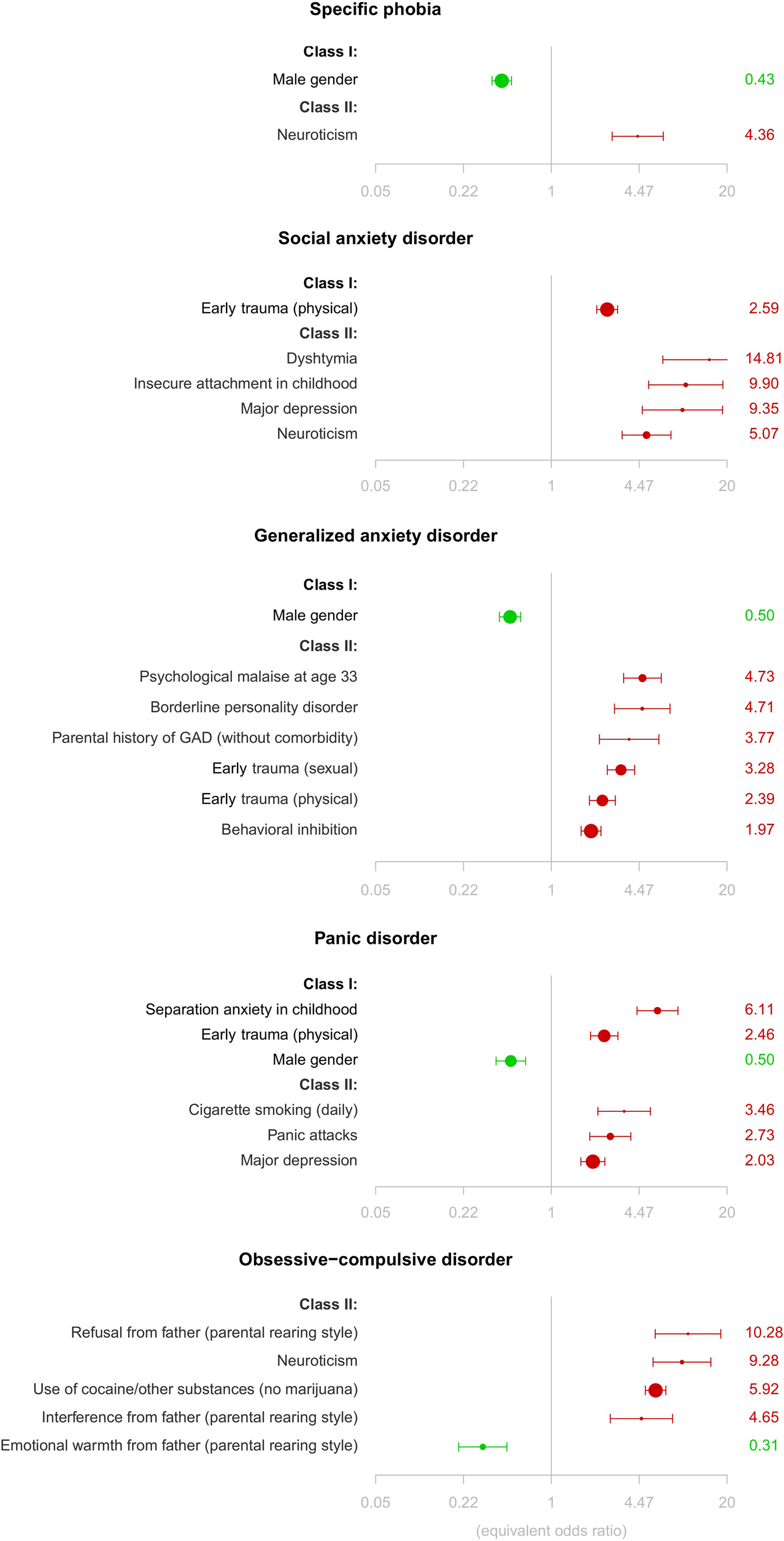

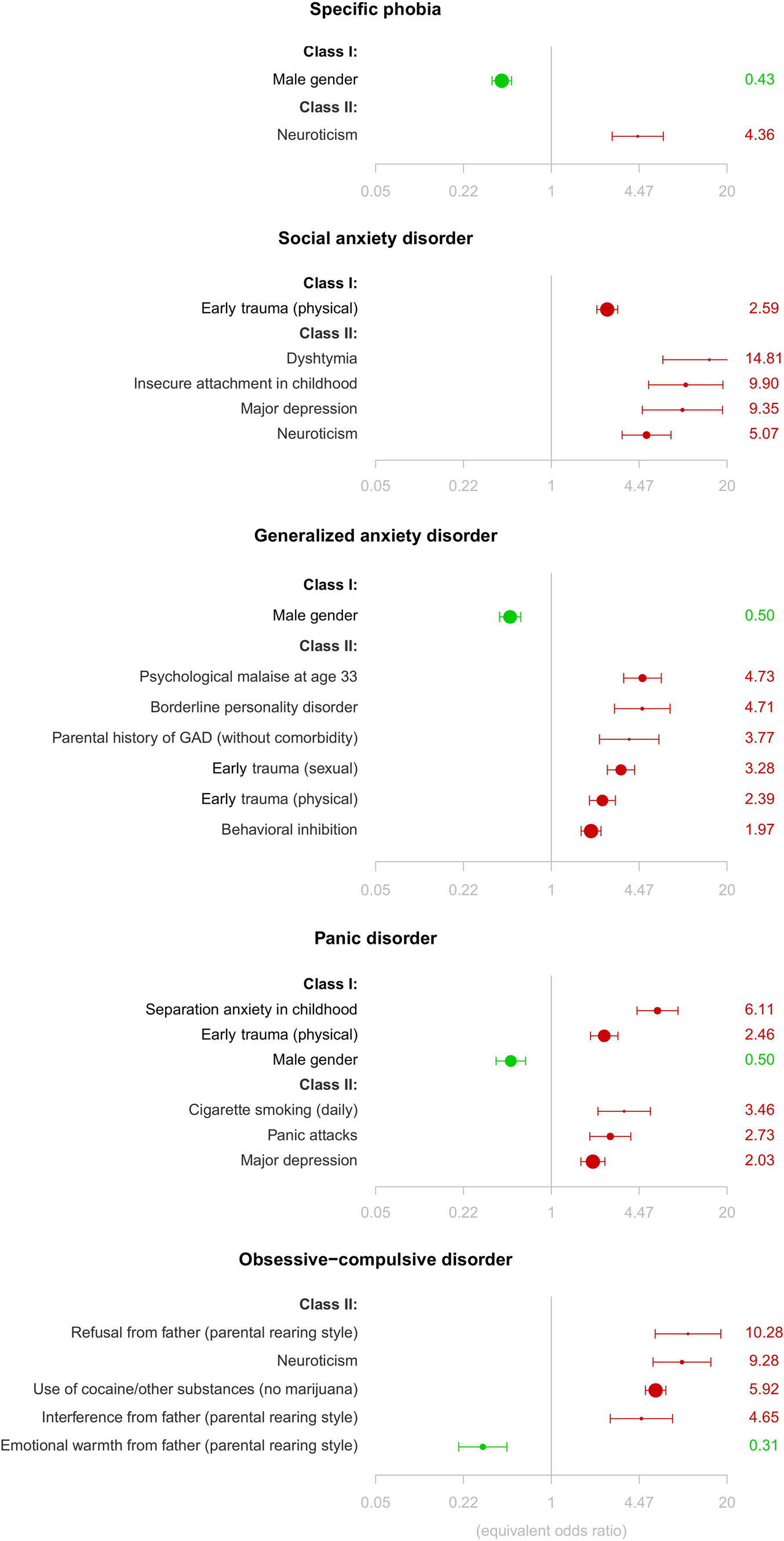

No factor showed convincing or highly suggestive evidence as a risk/protective factor for specific phobia using the original umbrella review criteria. Removing the n > 1000 criterion, being male showed convincing evidence as protective factor. Moreover, neuroticism showed highly suggestive evidence as risk factor for the disorder, which was maintained after the sensitivity analyses (Table 3, Fig. 2, and online Supplementary Table S4).

Fig. 2. Forest plots of risk (in red) and protective (in green) factors showing convincing (class I) or highly suggestive (class II) evidence of association with each disorder, after removing the n > 1000 cases criterion.

Social anxiety disorder

Early physical and sexual trauma showed, respectively, convincing and suggestive evidence as risk factors for SAD. Additionally, when removing the n > 1000 criterion, dysthymia, insecure attachment in childhood, major depression, and neuroticism showed highly suggestive evidence as risk factors for SAD. After sensitivity analyses, evidence for both trauma-related factors became weak, but the rest of factors–except insecure attachment in childhood- maintained the same level of evidence (Table 3, Fig. 2, and online Supplementary Table S4).

Generalized anxiety disorder

No factor showed convincing or highly suggestive evidence as a risk/protective factor for GAD. Removing the n > 1000 criterion, being male showed convincing evidence as protective factor for GAD and the following factors showed highly suggestive evidence as risk factors for the disorder: psychological malaise at age 33, borderline personality disorder, parental GAD without comorbidity, early physical and sexual trauma, and behavioral inhibition (assessed as a personality dimension). After sensitivity analyses, all these factors – except both trauma-related variables – maintained the same level of evidence (Table 3, Fig. 2, and online Supplementary Table S4).

Panic disorder

No factor showed convincing or highly suggestive evidence as risk/protective factor for PD. Removing the n > 1000 criterion, being male, separation anxiety in childhood, and early physical trauma showed convincing evidence as risk/protective factors for PD. The evidence was not maintained, however, after sensitivity analyses. Furthermore, daily cigarette smoking, panic attacks, and major depression showed highly suggestive evidence as risk factors for PD, which was maintained after sensitivity analyses (Table 3, Fig. 2, and online Supplementary Table S4).

Obsessive-compulsive disorder

No factor showed convincing or highly suggestive evidence as risk/protective factor for OCD. Removing the n > 1000 criterion, several parental rearing style variables, neuroticism, and use of cocaine together with another drug (except marijuana) showed highly suggestive evidence as risk/protective factors for OCD. However, the latter was based on a single study reporting one single case in the exposed group. Only neuroticism and use of cocaine together with another drug (except marijuana) maintained the same level of evidence after the sensitivity analyses (Table 3, Fig. 2, and online Supplementary Table S4).

Discussion

This is, to the best of our knowledge, the first umbrella review of risk/protective factors for anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorders. Our study provides a state-of-the-art classification of risk/protective factors based on the robustness of associations between these factors and five separate disorders, while controlling for several biases.

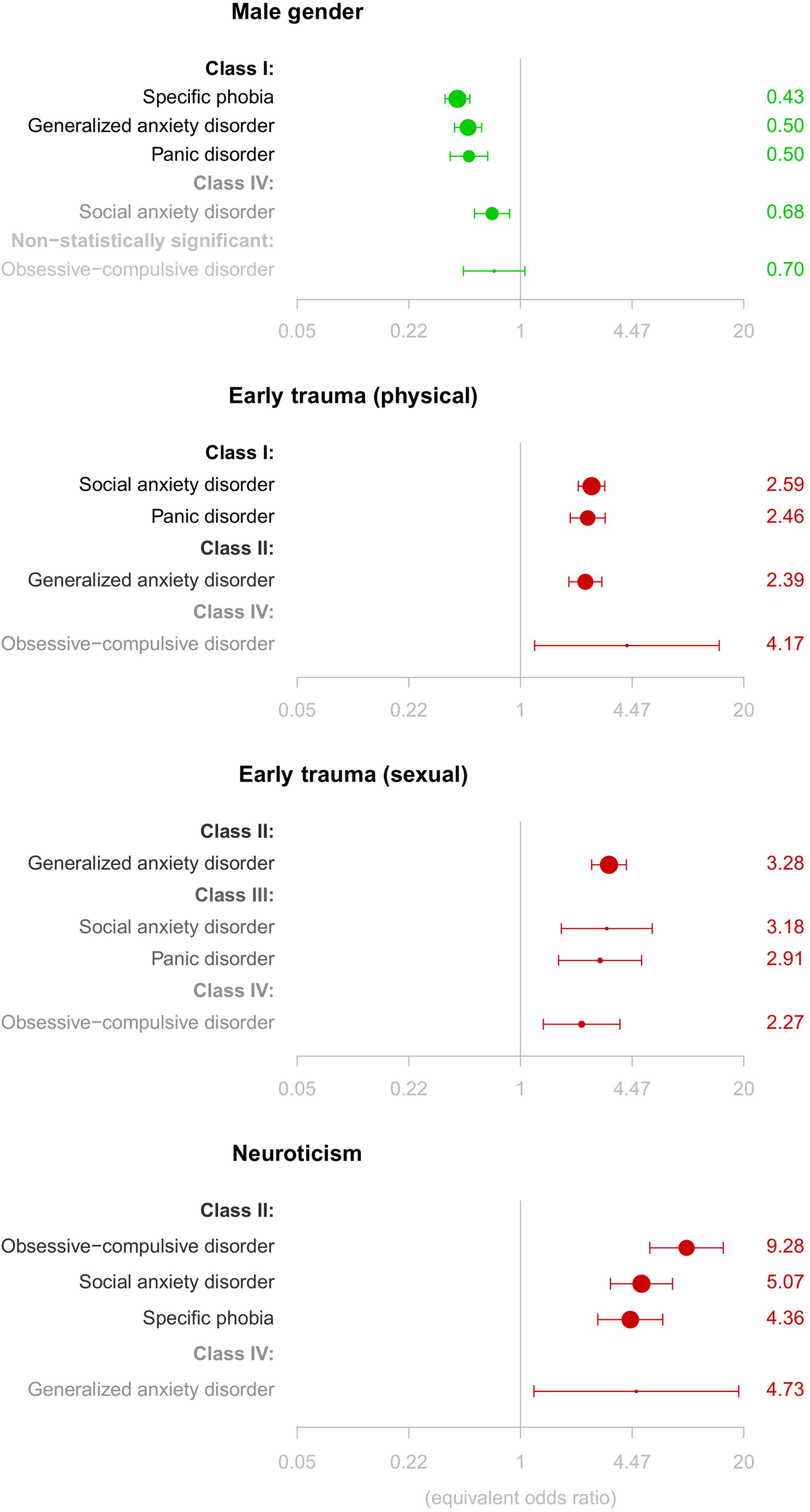

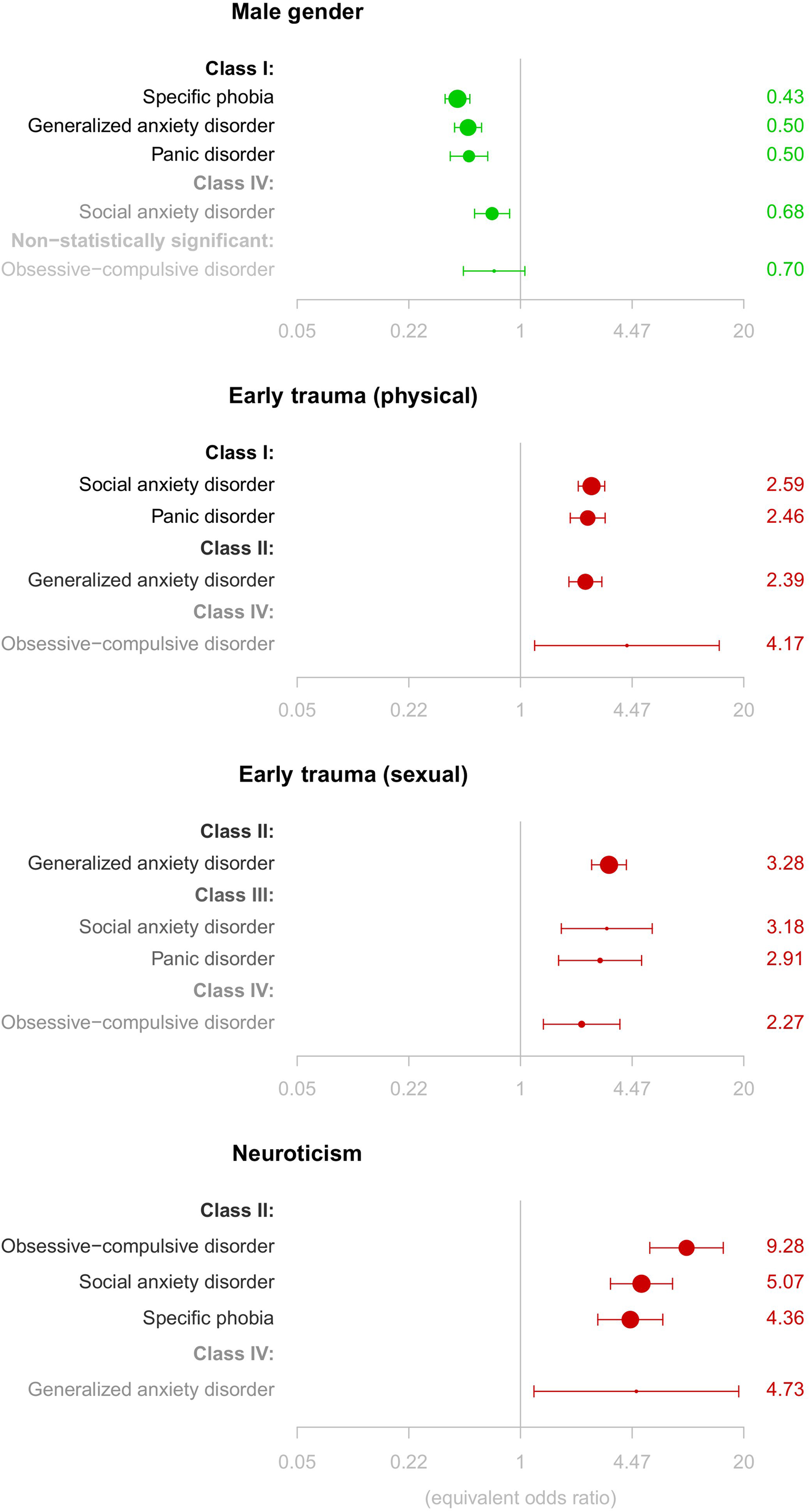

Using the original umbrella review criteria, early physical trauma was the single most consistent risk factor – class I – for SAD. Early sexual trauma was also associated – class III – with SAD. Several ‘traditional’ risk/protective factors for anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorders were among those that had nominally statistically significant results (Beesdo et al., Reference Beesdo, Knappe and Pine2009; Craske and Stein, Reference Craske and Stein2016). Although we could not assess exactly the same factors for all disorders, a number of factors showed a similar association with several of the disorders investigated (Fig. 3). For example, being male was associated with decreased risk for specific phobia, SAD, GAD, and PD; and neuroticism was associated with increased risk for specific phobia, SAD, GAD, and OCD. Moreover, early traumatic experiences increased the risk of all disorders in which they were investigated (SAD, GAD, PD, and OCD). Although the evidence for most of these associations was rated as weak, the consistency of these signals across multiple disorders strengthens the case that they do carry prognostic potential. The fact that the same factors increased the risk for different disorders may indicate a shared liability within anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorders (Blanco et al., Reference Blanco, Rubio, Wall, Wang, Jiu and Kendler2014). Moreover, some factors may be shared across mental disorders (i.e. be ‘transdiagnostic’). For example, early traumatic experiences are a significant risk factor for depressive (Köhler et al., Reference Köhler, Evangelou, Stubbs, Solmi, Veronese, Belbasis, Bortolato, Melo, Coelho, Fernandes, Olfson, Ioannidis and Carvalho2018), psychotic (Belbasis et al., Reference Belbasis, Köhler, Stefanis, Stubbs, van Os, Vieta, Seeman, Arango, Carvalho and Evangelou2018; Radua et al., Reference Radua, Ramella-Cravaro, Ioannidis, Reichenberg, Phiphopthatsanee, Amir, Yenn Thoo, Oliver, Davies, Morgan, McGuire, Murray and Fusar-Poli2018), and bipolar disorders (Bortolato et al., Reference Bortolato, Köhler, Evangelou, León-Caballero, Solmi, Stubbs, Belbasis, Pacchiarotti, Kessing, Berk, Vieta and Carvalho2017). Importantly, the results of our umbrella review provide hints not only on the presence/absence of a particular factor but also on the loading (weight) of that factor, which may be still unique (Uher and Zwicker, Reference Uher and Zwicker2017).

Fig. 3. Forest plots of risk/protective factors assessed in at least four of the disorders under study and showing convincing (class I) or highly suggestive (class II) evidence of association with at least one of the disorders, after removing the n > 1000 cases criterion.

The non-specificity of the findings for most risk factors investigated here (and probably for most risk factors for mental disorders in general) may also be partially explained by the fact that developmental effects (including temporal dynamics and the development of comorbidity over time) are often ignored in current nosological systems. The use of longitudinal ‘staging models’ – that describe the progression from more simple or ‘pure’ disorders to more complex or comorbid disorders – has been proposed to deal with these issues. Such models could offer a better description of the developmental patterns typical to most mental disorders (Beesdo et al., Reference Beesdo, Knappe and Pine2009).

Our data suggest that rather than ‘a few’ risk or protective factors with large effects, large sets of common ‘variants’ of small effects account for the risk for anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorders. This idea, which is well established in psychiatry genetics (Anttila et al., Reference Anttila, Bulik-Sullivan, Finucane, Walters, Bras, Duncan, Escott-Price, Falcone, Gormley, Malik, Patsopoulos, Ripke, Wei, Yu, Lee, Turley, Grenier-Boley, Chouraki, Kamatani, Berr, Letenneur, Hannequin, Amouyel, Boland, Deleuze, Duron, Vardarajan, Reitz, Goate, Huentelman, Kamboh, Larson, Rogaeva, St George-Hyslop, Hakonarson, Kukull, Farrer, Barnes, Beach, Demirci, Head, Hulette, Jicha, Kauwe, Kaye, Leverenz, Levey, Lieberman, Pankratz, Poon, Quinn, Saykin, Schneider, Smith, Sonnen, Stern, Van Deerlin, Van Eldik, Harold, Russo, Rubinsztein, Bayer, Tsolaki, Proitsi, Fox, Hampel, Owen, Mead, Passmore, Morgan, Nöthen, Schott, Rossor, Lupton, Hoffmann, Kornhuber, Lawlor, McQuillin, Al-Chalabi, Bis, Ruiz, Boada, Seshadri, Beiser, Rice, van der Lee, De Jager, Geschwind, Riemenschneider, Riedel-Heller, Rotter, Ransmayr, Hyman, Cruchaga, Alegret, Winsvold, Palta, Farh, Cuenca-Leon, Furlotte, Kurth, Ligthart, Terwindt, Freilinger, Ran, Gordon, Borck, Adams, Lehtimäki, Wedenoja, Buring, Schürks, Hrafnsdottir, Hottenga, Penninx, Artto, Kaunisto, Vepsäläinen, Martin, Montgomery, Kurki, Hämäläinen, Huang, Huang, Sandor, Webber, Muller-Myhsok, Schreiber, Salomaa, Loehrer, Göbel, Macaya, Pozo-Rosich, Hansen, Werge, Kaprio, Metspalu, Kubisch, Ferrari, Belin, van den Maagdenberg, Zwart, Boomsma, Eriksson, Olesen, Chasman, Nyholt, Anney, Avbersek, Baum, Berkovic, Bradfield, Buono, Catarino, Cossette, De Jonghe, Depondt, Dlugos, Ferraro, French, Hjalgrim, Jamnadas-Khoda, Kälviäinen, Kunz, Lerche, Leu, Lindhout, Lo, Lowenstein, McCormack, Møller, Molloy, Ng, Oliver, Privitera, Radtke, Ruppert, Sander, Schachter, Schankin, Scheffer, Schoch, Sisodiya, Smith, Sperling, Striano, Surges, Thomas, Visscher, Whelan, Zara, Heinzen, Marson, Becker, Stroink, Zimprich, Gasser, Gibbs, Heutink, Martinez, Morris, Sharma, Ryten, Mok, Pulit, Bevan, Holliday, Attia, Battey, Boncoraglio, Thijs, Chen, Mitchell, Rothwell, Sharma, Sudlow, Vicente, Markus, Kourkoulis, Pera, Raffeld, Silliman, Boraska Perica, Thornton, Huckins, William Rayner, Lewis, Gratacos, Rybakowski, Keski-Rahkonen, Raevuori, Hudson, Reichborn-Kjennerud, Monteleone, Karwautz, Mannik, Baker, O'Toole, Trace, Davis, Helder, Ehrlich, Herpertz-Dahlmann, Danner, van Elburg, Clementi, Forzan, Docampo, Lissowska, Hauser, Tortorella, Maj, Gonidakis, Tziouvas, Papezova, Yilmaz, Wagner, Cohen-Woods, Herms, Julià, Rabionet, Dick, Ripatti, Andreassen, Espeseth, Lundervold, Steen, Pinto, Scherer, Aschauer, Schosser, Alfredsson, Padyukov, Halmi, Mitchell, Strober, Bergen, Kaye, Szatkiewicz, Cormand, Ramos-Quiroga, Sánchez-Mora, Ribasés, Casas, Hervas, Arranz, Haavik, Zayats, Johansson, Williams, Elia, Dempfle, Rothenberger, Kuntsi, Oades, Banaschewski, Franke, Buitelaar, Arias Vasquez, Doyle, Reif, Lesch, Freitag, Rivero, Palmason, Romanos, Langley, Rietschel, Witt, Dalsgaard, Børglum, Waldman, Wilmot, Molly, Bau, Crosbie, Schachar, Loo, McGough, Grevet, Medland, Robinson, Weiss, Bacchelli, Bailey, Bal, Battaglia, Betancur, Bolton, Cantor, Celestino-Soper, Dawson, De Rubeis, Duque, Green, Klauck, Leboyer, Levitt, Maestrini, Mane, De-Luca, Parr, Regan, Reichenberg, Sandin, Vorstman, Wassink, Wijsman, Cook, Santangelo, Delorme, Rogé, Magalhaes, Arking, Schulze, Thompson, Strohmaier, Matthews, Melle, Morris, Blackwood, McIntosh, Bergen, Schalling, Jamain, Maaser, Fischer, Reinbold, Fullerton, Grigoroiu-Serbanescu, Guzman-Parra, Mayoral, Schofield, Cichon, Mühleisen, Degenhardt, Schumacher, Bauer, Mitchell, Gershon, Rice, Potash, Zandi, Craddock, Ferrier, Alda, Rouleau, Turecki, Ophoff, Pato, Anjorin, Stahl, Leber, Czerski, Edenberg, Cruceanu, Jones, Posthuma, Andlauer, Forstner, Streit, Baune, Air, Sinnamon, Wray, MacIntyre, Porteous, Homuth, Rivera, Grove, Middeldorp, Hickie, Pergadia, Mehta, Smit, Jansen, de Geus, Dunn, Li, Nauck, Schoevers, Beekman, Knowles, Viktorin, Arnold, Barr, Bedoya-Berrio, Joseph Bienvenu, Brentani, Burton, Camarena, Cappi, Cath, Cavallini, Cusi, Darrow, Denys, Derks, Dietrich, Fernandez, Figee, Freimer, Gerber, Grados, Greenberg, Hanna, Hartmann, Hirschtritt, Hoekstra, Huang, Huyser, Illmann, Jenike, Kuperman, Leventhal, Lochner, Lyon, Macciardi, Madruga-Garrido, Malaty, Maras, McGrath, Miguel, Mir, Nestadt, Nicolini, Okun, Pakstis, Paschou, Piacentini, Pittenger, Plessen, Ramensky, Ramos, Reus, Richter, Riddle, Robertson, Roessner, Rosário, Samuels, Sandor, Stein, Tsetsos, Van Nieuwerburgh, Weatherall, Wendland, Wolanczyk, Worbe, Zai, Goes, McLaughlin, Nestadt, Grabe, Depienne, Konkashbaev, Lanzagorta, Valencia-Duarte, Bramon, Buccola, Cahn, Cairns, Chong, Cohen, Crespo-Facorro, Crowley, Davidson, DeLisi, Dinan, Donohoe, Drapeau, Duan, Haan, Hougaard, Karachanak-Yankova, Khrunin, Klovins, Kučinskas, Chee Keong, Limborska, Loughland, Lönnqvist, Maher, Mattheisen, McDonald, Murphy, Murray, Nenadic, van Os, Pantelis, Pato, Petryshen, Quested, Roussos, Sanders, Schall, Schwab, Sim, So, Stögmann, Subramaniam, Toncheva, Waddington, Walters, Weiser, Cheng, Cloninger, Curtis, Gejman, Henskens, Mattingsdal, Oh, Scott, Webb, Breen, Churchhouse, Bulik, Daly, Dichgans, Faraone, Guerreiro, Holmans, Kendler, Koeleman, Mathews, Price, Scharf, Sklar, Williams, Wood, Cotsapas, Palotie, Smoller, Sullivan, Rosand, Corvin and Neale2018; Sullivan et al., Reference Sullivan, Agrawal, Bulik, Andreassen, Børglum, Breen, Cichon, Edenberg, Faraone, Gelernter, Mathews, Nievergelt, Smoller and O'Donovan2018), seems to be also true for ‘non-purely genetic’ factors (Uher and Zwicker, Reference Uher and Zwicker2017). Furthermore, our findings open the door to the potential development of enhanced risk prediction models (Bernardini et al., Reference Bernardini, Attademo, Cleary, Luther, Shim, Quartesan and Compton2017) and individual risk prediction scores (see Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Rose, Koenen, Karam, Stang, Stein, Heeringa, Hill, Liberzon, McLaughlin, McLean, Pennell, Petukhova, Rosellini, Ruscio, Shahly, Shalev, Silove, Zaslavsky, Angermeyer, Bromet, De Almeida, De Girolamo, De Jonge, Demyttenaere, Florescu, Gureje, Haro, Hinkov, Kawakami, Kovess-Masfety, Lee, Medina-Mora, Murphy, Navarro-Mateu, Piazza, Posada-Villa, Scott, Torres and Viana2014, and Shalev et al., Reference Shalev, Gevonden, Ratanatharathorn, Laska, van der Mei, Qi, Lowe, Lai, Bryant, Delahanty, Matsuoka, Olff, Schnyder, Seedat, DeRoon-Cassini, Kessler and Koenen2019 for specific examples in PTSD). In recent years, the use of polygenic risk scores has been validated in disorders such as schizophrenia (International Schizophrenia Consortium et al., Reference Purcell, Wray, Stone, Visscher, O'Donovan, Sullivan and Sklar2009). More recently, the use of ‘poly-environmental scores’ has been proposed (Padmanabhan et al., Reference Padmanabhan, Shah, Tandon and Keshavan2017; Uher and Zwicker, Reference Uher and Zwicker2017). Given that multiple genetic and non-genetic factors have much greater explanatory power than considering them one at a time in most mental disorders (Uher and Zwicker, Reference Uher and Zwicker2017), it is likely that ‘poly-risk’ scores (containing both genetic and non-genetic factors) improve the prediction of mental disorders. Our data may help developing such scores for anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorders, although the time of exposure and the cumulative nature of non-genetic risk will need to be taken into account to improve such prediction abilities (Moffitt et al., Reference Moffitt, Caspi and Rutter2005; Sharma et al., Reference Sharma, Powers, Bradley and Ressler2016). Developmental effects – and their potential interaction with genetic variables- are difficult to study using epidemiological data, but they could be investigated using animal models (Leonardo and Hen, Reference Leonardo and Hen2008).

The majority of factors were only classified as having weak evidence (class IV). This mainly reflects the methodological limitations of the data, where less than 5% of the factors included more than 1000 cases and where the significance of the associations for each individual factor was overall low. The (weak) strength of the associations found, together with limitations inherent to the individual study designs employed to date, precludes firm causal inferences for any of the significant factors identified in our umbrella review (Paulus, Reference Paulus2015). Future work to identify risk/protective factors could focus on large-scale family-based designs, that allow for a more stringent control of unmeasured familial confounders (D'Onofrio et al., Reference D'Onofrio, Lahey, Turkheimer and Lichtenstein2013) and should improve the confidence in the identification of ‘non-purely genetic’ risk/protective factors that are in the causal pathway for anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorders. For example, recent population-based work in OCD has confirmed that a range of perinatal complications are robustly associated with the disorder, even after strict control of unmeasured genetic and environmental confounders, and that the number of perinatal complications cumulatively contribute to risk for the disorder (Brander et al., Reference Brander, Rydell, Kuja-Halkola, Fernández de la Cruz, Lichtenstein, Serlachius, Rk, Almqvist, D'Onofrio, Larsson and Mataix-Cols2016b). Similarly, as the field of psychiatric genetics is clearly shifting away from the candidate gene approach into the less arbitrary genome-wide association studies (GWAS) approach, the identification of genetic variants implicated in these disorders should increase dramatically in the next few years, as exemplified by the recent formation of an anxiety disorders group within the psychiatric genetics consortium (Sullivan et al., Reference Sullivan, Agrawal, Bulik, Andreassen, Børglum, Breen, Cichon, Edenberg, Faraone, Gelernter, Mathews, Nievergelt, Smoller and O'Donovan2018).

We also note that we identified very few protective factors that were not reciprocal to risk factors. This indicates that most research so far has focused on adverse/negative factors, and highlights another important aspect that will need to be addressed in future studies.

Our results may also offer opportunities for prevention. Current prevention programs for anxiety disorders have shown modest benefits (Moreno-Peral et al., Reference Moreno-Peral, Conejo-Cerón, Rubio-Valera, Fernández, Navas-Campaña, Rodríguez-Morejón, Motrico, Rigabert, De Dios Luna, Martín-Pérez, Rodríguez-Bayón, Ballesta-Rodríguez, Luciano and Bellón2017) and there is a need for new strategies. Our findings lend support to identifying those individuals with several risk factors for inclusion in prevention programs (Blanco et al., Reference Blanco, Rubio, Wall, Wang, Jiu and Kendler2014). Large sets of risk factors of small effects seem to account for the risk for anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorders, and therefore interventions that try to modulate several of them concurrently should be devised. For example, parental psychopathology and parental rearing styles were significant risk factors for several of the disorders investigated here and could be a combined target for prevention efforts. Recent data on moderators and mediators of prevention strategies should help optimise such efforts (Ginsburg et al., Reference Ginsburg, Drake, Tein, Teetsel and Riddle2015). Our results also support focusing on those modifiable risk factors with the largest effects (e.g. trauma), and whose reduction would have a greater prospective impact (Li et al., Reference Li, D'Arcy and Meng2016). Claims of success should await the results of randomized trials, since observational associations may not necessarily represent causal effects.

Our study has several strengths. We used systematic search methods and both the study selection and data extraction were conducted by independent raters. Moreover, we assessed that each individual study included in the systematic review or meta-analysis fulfilled our inclusion criteria and used standard approaches to assess the methodological quality of the systematic reviews or meta-analysis (Fusar-Poli and Radua, Reference Fusar-Poli and Radua2018). We offer as online Supplementary material all data collected in our umbrella review. Beyond encouraging open science, this databank may contribute to the creation of a database of risk/protective factors for anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorders that can be updated in the future. We also note several limitations. First, we assessed each of disorders separately and did not use a mixed ‘anxiety disorders’ category as an outcome. There have been changes in the specific disorders included under the ‘anxiety disorders’ category, complicating the interpretation of such analyses. Second, we collected only information about factors assessed in systematic reviews and meta-analyses, and studies not included in this type of publication were not eligible for inclusion. Moreover, not all factors were evaluated for all the disorders. Third, we did not assess the quality of the individual studies included in the systematic reviews and meta-analyses (because this is beyond the scope of an umbrella review). Moreover, there may be differences across-studies in the exact definitions and methods of assessment for each factor. Finally, the almost ubiquitously limited amount of evidence made us explore also what would happen if we removed the need for >1000 cases to have highly suggestive evidence. Nevertheless, great caution is needed in trusting associations, no matter how strong and consistent, where data are sparse.

In summary, we found a number of nominally statistically significant risk and protective factors for anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorders, although very few were supported by robust evidence. The limited amount of evidence was the main restricting factor, and this means that there is plenty of room to improve the standards of evidence in this field. Our findings may help optimize current prediction models and may provide hints for testing prevention strategies.

Author ORCIDs

Miquel A. Fullana, 0000-0003-3863-5223.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291719001247.

Acknowledgements

Dr Fernández de la Cruz is supported by a Junior Researcher grant from the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare (FORTE grant number 2015-00569). Ms. Pérez-Vigil is supported by a grant from the Alicia Koplowitz Foundation. Drs. Vieta, Radua, and Fatjó-Vilas have received support from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness of Spain (PI 12/00912; CP14/00041; CD16/00264), integrated into the Plan Nacional de I+D+I and cofounded by ISCIII- Subdirección General de Evaluación and Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER) and Centro para la Investigación Biomédica en Red de Salud Mental (CIBERSAM). Dr Vieta has also received support from Secretaria d'Universitats i Recerca del Departament d'Economia i Coneixement (2014_SGR_398), Seventh European Framework Programme (ENBREC), and the Stanley Medical Research Institute. Dr Fatjó-Vilas has also received support from Comissionat per a Universitats i Recerca del DIUE, of the Generalitat de Catalunya regional authorities (2017_SGR_1271).

Conflict of interest

Dr Fernández de la Cruz and Prof. Mataix-Cols receive royalties for contributing articles to UpToDate, Wolters Kluwer Health. Dr Vieta has received grants and honoraria from AB-Biotics, Allergan, Angelini, AstraZeneca, Ferrer, Forest Research Institute, Gedeon Richter, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Lundbeck, Medscape, Otsuka, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, Sunovion, and Takeda as well as from the CIBERSAM, Grups Consolidats de Recerca 2014 (SGR 398), the Seventh European Framework Programme (ENBREC), Horizon 2020 (R-LINK) and the Stanley Medical Research Institute. The rest of authors report no competing interests.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.