Introduction

Successful interventions to improve the core cognitive deficits of schizophrenia continue to be a critical research frontier (Green, Reference Green2016; Green & Nuechterlein, Reference Green and Nuechterlein1999; Marder & Fenton, Reference Marder and Fenton2004; Vinogradov & Schulz, Reference Vinogradov and Schulz2016). Meta-analyses have indicated that patients with long-term schizophrenia participating in cognitive remediation (CR) show moderate improvements in cognition, with Cohen's d effect sizes of 0.41 (S. R. McGurk, Twamley, Sitzer, McHugo, and Mueser, Reference McGurk, Twamley, Sitzer, McHugo and Mueser2007) and 0.43 (Wykes, Huddy, Cellard, McGurk, & Czobor, Reference Wykes, Huddy, Cellard, McGurk and Czobor2011).

The impact of CR for recently diagnosed schizophrenia patients has begun to be examined (Revell, Neill, Harte, Khan, & Drake, Reference Revell, Neill, Harte, Khan and Drake2015). The effects of CR might be expected to be even larger in recent-onset schizophrenia patients than in patients with long-term illness, given that gains would occur before further decrements in cognitive functioning, more severe brain anomalies, and chronic disability patterns have been established (Bowie, Grossman, Gupta, Oyewumi, & Harvey, Reference Bowie, Grossman, Gupta, Oyewumi and Harvey2014; Insel, Reference Insel2016). However, a meta-analysis by Revell et al. (Reference Revell, Neill, Harte, Khan and Drake2015) of 11 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of CR with patients in early phases of schizophrenia found that the standardized mean effect sizes for cognition (0.19) and everyday functioning (0.18) were actually smaller than found in chronic schizophrenia patients (Wykes et al., Reference Wykes, Huddy, Cellard, McGurk and Czobor2011). The study with the largest effect on cognition (0.49) showed very promising effects on overall cognition, verbal memory, and problem-solving (Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Loewy, Carter, Lee, Ragland, Niendam and Vinogradov2015). Several additional studies with early course patients showed promising effects on social cognition, verbal memory, processing speed, and working memory (Bowie et al., Reference Bowie, Grossman, Gupta, Oyewumi and Harvey2014; Eack, Hogarty, Greenwald, Hogarty, & Keshavan, Reference Eack, Hogarty, Greenwald, Hogarty and Keshavan2007; Wykes et al., Reference Wykes, Newton, Landau, Rice, Thompson and Frangou2007). However, other RCTs in the early course of schizophrenia found no significant overall cognitive benefit (Holzer et al., Reference Holzer, Urben, Passini, Jaugey, Herzog, Halfon and Pihet2014; Ueland & Rund, Reference Ueland and Rund2004), or found no overall cognitive gain but significant gain in one cognitive domain (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Redoblado-Hodge, Naismith, Hermens, Porter and Hickie2013).

The Revell et al. meta-analysis included RCTs of first-episode psychosis as well as studies of early-onset schizophrenia and studies of relatively early phases of schizophrenia that are not typical first-episode schizophrenia samples. Thus, some studies included patients whose first psychosis onset was as long as 5 years (Bowie et al., Reference Bowie, Grossman, Gupta, Oyewumi and Harvey2014; Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Loewy, Carter, Lee, Ragland, Niendam and Vinogradov2015) or 8 years (Eack et al., Reference Eack, Greenwald, Hogarty, Cooley, DiBarry, Montrose and Keshavan2009) prior to study entry. Other studies indicated that the psychosis had an onset in adolescence but did not restrict their samples to psychotic illnesses of any specific duration (Holzer et al., Reference Holzer, Urben, Passini, Jaugey, Herzog, Halfon and Pihet2014; Puig et al., Reference Puig, Penades, Baeza, De la Serna, Sanchez-Gistau, Bernardo and Castro-Fornieles2014). Some studies included psychoses not schizophrenia-related or had small sample sizes (Bowie et al., Reference Bowie, Grossman, Gupta, Oyewumi and Harvey2014; Ueland & Rund, Reference Ueland and Rund2004). Although one study involved a 2-year period (Eack et al., Reference Eack, Greenwald, Hogarty, Cooley, DiBarry, Montrose and Keshavan2009), most studies used only 2–3 months of cognitive training. Thus, additional studies of substantial duration that focus on the initial period after the first episode in schizophrenia-related psychoses would be very helpful.

Most of these CR studies (Revell et al., Reference Revell, Neill, Harte, Khan and Drake2015) but not all (Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Loewy, Carter, Lee, Ragland, Niendam and Vinogradov2015) found that everyday functioning had improved to some degree. One study found larger improvements in early course patients than in long-term illness patients (Bowie et al., Reference Bowie, Grossman, Gupta, Oyewumi and Harvey2014), and another found that cognitive gains were associated with functional improvement (Wykes et al., Reference Wykes, Newton, Landau, Rice, Thompson and Frangou2007). Revell et al. (Reference Revell, Neill, Harte, Khan and Drake2015) found that CR programs within a context of vocational or educational training tend to improve cognitive and work functioning to a greater extent than CR alone, as is true in longer-term schizophrenia (Wykes et al., Reference Wykes, Huddy, Cellard, McGurk and Czobor2011). Supported education/employment has demonstrated an ability to double the proportion of first-episode psychosis patients who return to work or school (Killackey, Jackson, & McGorry, Reference Killackey, Jackson and McGorry2008; Nuechterlein et al., Reference Nuechterlein, Subotnik, Ventura, Turner, Gitlin, Gretchen-Doorly and Liberman2020). Given the benefits of supported education/employment, early intervention, and the link between cognition and functioning, perhaps adding CR to supported education/employment could boost functional gains, as McGurk and colleagues found with long-term schizophrenia patients (McGurk, Mueser, & Pascaris, Reference McGurk, Mueser and Pascaris2005). No prior published studies have examined the impact of CR in the context of supported education/employment after the first episode of schizophrenia.

Another limitation of prior RCTs of CR in the initial phase of schizophrenia is that the comparison group has usually been treatment-as-usual without an attempt to match treatment intensity (Revell et al., Reference Revell, Neill, Harte, Khan and Drake2015). The exception so far has involved computer games, which equated for computer exposure (Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Loewy, Carter, Lee, Ragland, Niendam and Vinogradov2015; Holzer et al., Reference Holzer, Urben, Passini, Jaugey, Herzog, Halfon and Pihet2014). We chose to develop Healthy Behaviors Training (HBT) as a comparison psychosocial intervention, as we wanted an equally engaging and intensive treatment that did not primarily target cognitive improvement (Gretchen-Doorly, Subotnik, Kite, Alarcon, & Nuechterlein, Reference Gretchen-Doorly, Subotnik, Kite, Alarcon and Nuechterlein2009). Health-focused programs have been implemented successfully for schizophrenia patients (Brar et al., Reference Brar, Ganguli, Pandina, Turkoz, Berry and Mahmoud2005; Evans, Newton, & Higgins, Reference Evans, Newton and Higgins2005; Littrell, Hilligoss, Kirshner, Petty, & Johnson, Reference Littrell, Hilligoss, Kirshner, Petty and Johnson2003; Weber & Wyne, Reference Weber and Wyne2006).

Systematic consideration of antipsychotic medication adherence effects has also been absent from studies of CR in the early course of schizophrenia. While differences among antipsychotic medications in effect on cognition are often small in schizophrenia (Keefe & Harvey, Reference Keefe and Harvey2012) even after the first episode (Davidson et al., Reference Davidson, Galderisi, Weiser, Werbeloff, Fleischhacker, Keefe and Kahn2009; Harvey, Rabinowitz, Eerdekens, & Davidson, Reference Harvey, Rabinowitz, Eerdekens and Davidson2005; Keefe et al., Reference Keefe, Seidman, Christensen, Hamer, Sharma, Sitskoorn and Lieberman2004), the impact of medication adherence on cognition has not been as systematically examined in the period after the first episode, particularly in the context of CR. Periods of medication nonadherence with oral antipsychotics are extremely common in the initial years of schizophrenia and are a major clinical problem (Subotnik et al., Reference Subotnik, Nuechterlein, Ventura, Gitlin, Marder, Mintz and Singh2011; Weiden, Mott, & Curcio, Reference Weiden, Mott, Curcio, Shriqui and Nasrallah1995). Our research (Subotnik et al., Reference Subotnik, Casaus, Ventura, Luo, Hellemann, Gretchen-Doorly and Nuechterlein2015) suggests that the impact of long-acting antipsychotic medication on consistent antipsychotic medication adherence and on psychotic exacerbation or relapse after the first episode of schizophrenia are much greater than typically seen in chronic phases of the illness (Kishimoto et al., Reference Kishimoto, Robenzadeh, Leucht, Leucht, Watanabe, Mimura and Correll2014). Psychotic relapses may disrupt recovery of cognitive functioning in the early course of schizophrenia. In addition, we have found that long-acting antipsychotic medication preserves intracortical myelin in the frontal lobe (Bartzokis et al., Reference Bartzokis, Lu, Raven, Amar, Detore, Couvrette and Nuechterlein2012), which should enhance the speed of processing information. Thus, we hypothesized that the beneficial effects of long-acting antipsychotic medication and consistent antipsychotic medication adherence would extend to cognition and work outcome in first-episode patients. We also sought to examine whether long-acting antipsychotic medication and associated medication adherence would enhance the impact of CR after a first episode. We used random assignment to long-acting v. oral risperidone to enhance medication adherence. We also created a continuous index of medication adherence to further examine the impact of this variable on cognition.

Methods

Research design and Key hypotheses

As described in ClinicalTrials.gov NCT00333177, this RCT employed a 2 × 2 fully crossed design with the assignment to CR v. HBT and to oral v. long-acting injectable (LAI) risperidone. The clinical treatment team was the same for all patients, with an equal amount of treatment time provided within each of the four treatment combinations. The clinical team was not blind to treatment assignment, but each treatment option was viewed as equally desirable by this team. If the study psychiatrist decided that the assigned medication led to intolerable side effects or was clearly ineffective, the patient was switched to another second-generation oral antipsychotic but continued in the assigned CR or HBT treatment. The primary outcome variables were the MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery (MCCB) Overall Composite T score for cognition, the Global Functioning Scale: Role for work/school functioning, the Work section of the Modified Social Adjustment Scale for maintenance of work/school attendance, and a continuous index of medication adherence.

The primary hypotheses were (1) cognitive remediation will lead to larger cognitive gains and better work/school outcomes than healthy behavior training, (2) LAI risperidone will increase medication adherence, cognitive gains, and work/school outcome, (3) medication adherence will enhance the impact of cognitive remediation after the first psychotic episode, and (4) cognitive gain will predict the amount of work/school functioning improvement.

Participants

The sample consisted of 60 participants recruited from Los Angeles psychiatric hospitals and clinics. All participants received outpatient psychiatric treatment at the UCLA Aftercare Research Program and were participants in the fourth phase of the Developmental Processes in Schizophrenic Disorders Project (Nuechterlein et al., Reference Nuechterlein, Ventura, Subotnik, Hayata, Medalia and Bell2014; Subotnik et al., Reference Subotnik, Casaus, Ventura, Luo, Hellemann, Gretchen-Doorly and Nuechterlein2015). This study was approved by the UCLA IRB; all participants gave written informed consent.

Entry criteria were: (1) a recent onset of psychotic illness, with the first psychotic episode beginning within the last 2 years; (2) a DSM-IV diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, depressed type, or schizophreniform disorder; (3) 18–45 years of age; (4) no evidence of known neurological disorder; (5) no evidence of significant and habitual drug abuse or alcoholism in the 6 months prior to study entry and no evidence that the psychosis was substance-induced; (6) premorbid IQ not less than 70; (7) sufficient fluency in English to avoid invalidating research measures; (8) residence within commuting distance of UCLA; and (9) treatment with risperidone was not contraindicated. The diagnosis was established through a Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV plus information from family members and treating professionals.

Treatments provided to all participants

Upon clinic entry, a master's or doctoral level therapist and a psychiatrist were assigned to each patient and typically met with the patient weekly. The therapist provided case management and supportive, skills-focused therapy. Given the success of supported education/employment in aiding return to work or school in our prior study (Nuechterlein et al., Reference Nuechterlein, Subotnik, Ventura, Turner, Gitlin, Gretchen-Doorly and Liberman2020; Nuechterlein, Subotnik, et al., Reference Nuechterlein, Subotnik, Turner, Ventura, Becker and Drake2008), we sought to build on that foundation by having an Individual Placement and Support (IPS) specialist work with all patients to assist them in finding schooling or competitive employment. IPS fidelity was good (101 on IPS-25) (Becker, Swanson, Bond, & Merrens, Reference Becker, Swanson, Bond and Merrens2008).

Randomized medication conditions: oral risperidone v. long-acting injectable risperidone

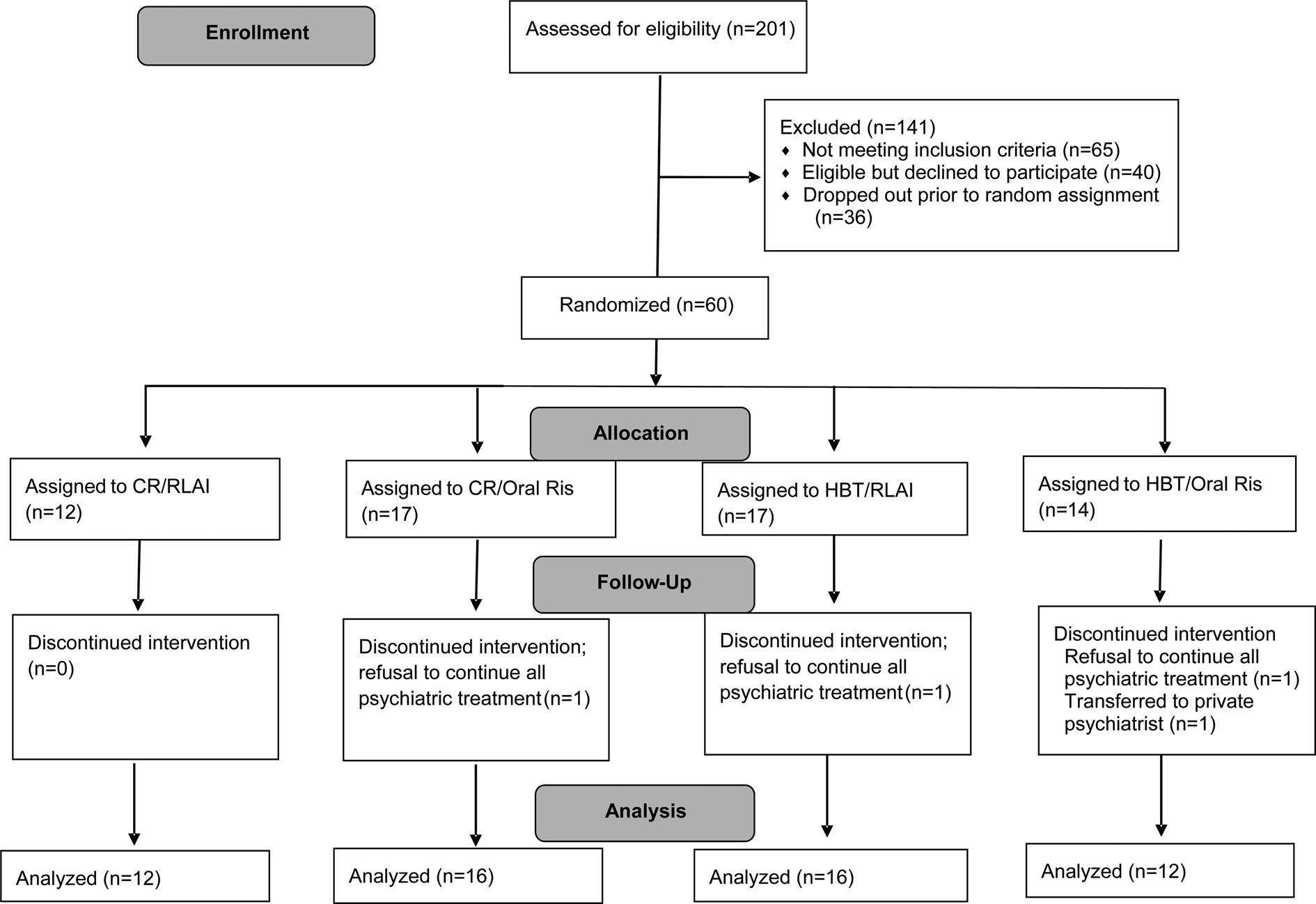

Patients were typically actively psychotic upon project entry. Patients were gradually cross-tapered to oral risperidone if not already on this medication. Then we used a lead-in period of oral risperidone as the sole antipsychotic medication for at least 3 weeks. Patients then completed baseline assessments over 4–6 weeks and were randomly assigned to continued treatment with oral risperidone (Oral) or to LAI risperidone. Dosages were optimized by the psychiatrists with feedback from patients. Initial LAI dosage was 25 mg with adjustments as needed afterward. Although patients had typically achieved clinical stability prior to randomization, symptom severity level was not a criterion for proceeding to randomization. Median duration between clinic enrollment and randomization was 5.0 months (mean = 5.8 months, s.d. = 3.6). See Fig. 1 for the recruitment and enrollment flowchart.

Fig. 1. CONSORT diagram of the progress of patients through the phases of the RCT.

Following randomization, study psychiatrists could prescribe a different second-generation antipsychotic medication if inadequate clinical response to risperidone or intolerable side effects were observed. Introduction of a second, adjunctive antipsychotic medication other than risperidone also concluded an individual's medication trial. Oral risperidone was provided during the first 2-3 weeks of LAI treatment but rarely beyond that point.

Randomized psychosocial treatment: cognitive remediation or healthy behaviors training

Patients were randomized to CR or HBT at the same time as the medication randomization occurred. A randomization table with four digits was used to assign patients to the 2 × 2 treatment design. Patients in CR participated in a computer-assisted cognitive training program for 6 months, 2 hours/week (on separate clinic visits), followed by 1 hour/week for 3 months and then 1 hour every other week for 3 months. A series of 23 cognitive training programs, each with graduated levels of difficulty, were used in a group ‘computer lab’ with cognitive trainers (Nuechterlein et al., Reference Nuechterlein, Ventura, Subotnik, Hayata, Medalia and Bell2014). CR groups had 4–5 patients with one trainer. The CR program combined restorative approaches from Neurocognitive Enhancement Therapy (NET) (Bell, Bryson, Greig, Corcoran, & Wexler, Reference Bell, Bryson, Greig, Corcoran and Wexler2001) and Neuropsychological Educational Approach to Remediation (NEAR) (Medalia, Revheim, & Herlands, Reference Medalia, Revheim and Herlands2009) that targeted cognitive skills ranging from processing speed and attention to memory and problem solving (see online Supplementary Table 1). Programs began with training in lower-level cognitive functions (simple reaction time) and progressed to verbal and visual memory and then to increasingly complex, life-like problem-solving tasks. Programs provided ongoing feedback on performance. The cognitive trainers provided additional positive feedback as program goals were reached, moved patients to the next program, and suggested task strategies as needed, following coaching procedures described in Medalia et al. (Reference Medalia, Revheim and Herlands2009). Patients also attended a 1-hour Bridging Group weekly in the first 9 months and every other week for the next 3 months. The Bridging Group facilitated connections between training and work/school performance (Bell et al., Reference Bell, Bryson, Greig, Corcoran and Wexler2001; Medalia et al., Reference Medalia, Revheim and Herlands2009) by helping patients apply cognitive skills learned in the computerized tasks to real-world situations. CR training was provided by Alice Medalia and Joanna Fizdon; regular phone supervision with Alice Medalia enhanced fidelity. Further CR details are reported separately (Nuechterlein et al., Reference Nuechterlein, Ventura, Subotnik, Hayata, Medalia and Bell2014).

The HBT was designed to improve lifestyle habits and well-being. We followed the US National Consensus Statement on Mental Health Recovery (SAMHSA, 2006) that emphasizes the development of holistic well-being through strength-based interventions that build resilience and increase self-determination. Our HBT program (a) educated patients about important concepts in nutrition, physical exercise and stress management, (b) taught essential skills for implementing concepts learned, and (c) engaged patients in periodic, low-intensity exercise to improve physical health. The 12-month HBT program was a manual-driven program rotating through the three topics (i.e. nutrition, stress management, and fitness) every 3 weeks. We designed the HBT program to provide an equal amount of group treatment time as the CR program, again based on group sessions with 4–5 patients (Gretchen-Doorly et al., Reference Gretchen-Doorly, Subotnik, Kite, Alarcon and Nuechterlein2009; Gretchen-Doorly, Subotnik, Ventura, & Nuechterlein, Reference Gretchen-Doorly, Subotnik, Ventura and Nuechterlein2012; Ventura et al., Reference Ventura, Subotnik, Gretchen-Doorly, Casaus, Boucher, Medalia and Nuechterlein2019). HBT involved 3 h/week for 6 months, followed by 2 h/week for 3 months and then 2 h every other week for the last 3 months. Each unit included didactic instruction and a group activity to create mastery-building experiences. Nutrition units included instruction in portion control, healthy snacking, managing hunger, overcoming barriers to a healthy lifestyle, and live demonstrations on cooking healthy meals. Stress management units included identifying personal stress triggers, learning effective problem-solving skills, and practice with stress-relieving techniques. Fitness units included 1 hour of didactic instruction plus 30 min of on-site, supervised physical exercise every 3 weeks.

Measurement of medication nonadherence

A dimensional index of medication nonadherence was created as a rating on a 1–5 scale (1 = excellent adherence, 5 = very poor adherence) based on the timeliness of injections for injectable medication, and on pill counts, patient reports, plasma levels, Medication Event Monitoring System (MEMS™) data, and psychiatrist judgments for the oral medication (Subotnik et al., Reference Subotnik, Casaus, Ventura, Luo, Hellemann, Gretchen-Doorly and Nuechterlein2015). Pill counts, patient self-report, and clinician judgments were completed every 1–2 weeks. Plasma risperidone and 9-hydroxyrisperidone levels were obtained every 4 weeks in the Oral condition, and typically at weeks 8 and 12 for LAI. All information sources were combined by research assistants to yield the nonadherence rating every 2 weeks. The mean level of nonadherence was computed for the entire time that Oral or LAI risperidone treatment was provided (until a medication change occurred or the 12-month point was reached).

Measurement of cognition and work/school functioning

The MCCB (Nuechterlein, Green, et al., Reference Nuechterlein, Green, Kern, Baade, Barch, Cohen and Marder2008) was administered at baseline, 6 months, and 12 months to provide a standardized assessment of cognitive functioning. Testers were trained by didactic instruction, observing MCCB administration, and then being observed by experts for three administrations. The Global Functioning Scale: Role (Cornblatt et al., Reference Cornblatt, Auther, Niendam, Smith, Zinberg, Bearden and Cannon2007; Niendam, Bearden, Johnson, & Cannon, Reference Niendam, Bearden, Johnson and Cannon2006), a 10-point scale measuring a combination of quantity and quality of work/school functioning, was completed by the individual therapists every 3 months based on their ongoing interactions with the patients, family members, and employers or teachers. Mean interrater reliability was r = 0.91. A modified interview-based version of the work section of the Social Adjustment Scale (Weissman & Bothwell, Reference Weissman and Bothwell1976) was used to assess employment or enrollment in school (Subotnik et al., Reference Subotnik, Nuechterlein, Kelly, Kupic, Brosemer and Turner2008), completed by the individual therapists every 3 months. Mean interrater reliability for judging presence at competitive work or regular schooling was Kappa = .84.

Data analyses

All analyses were completed using SPSS Statistics v25 GLM and Correlation modules. Medication effects were examined through dichotomous (LAI-Oral) as well as dimensional (medication adherence index) approaches. For dichotomous analyses, 2 (LAI v. Oral) × 2 (CR v. HBT) × Time repeated measures ANCOVAs were employed for cognitive and work/school outcomes. The baseline value of the dependent variable was covaried to control for any impact of initial value on outcome. As planned for this RCT, outcomes after the initial 6 months of more intensive psychosocial treatment were examined separately from 12-month outcomes. Because almost all LAI patients but also some Oral risperidone patients showed high medication adherence, the dimensional index offers a supplementary, sensitive way to examine antipsychotic adherence effects across medication groups. Dimensional analyses included correlations between the adherence index and cognitive gain as well as examination of CT v. HBT impact with the medication adherence index covaried.

For 10 MCCB administrations, one of the 10 individual tests could not be completed. To allow Overall Composite Scores to be computed by the MCCB Computer Scoring Program, multiple imputation of the missing individual test score was conducted using age, gender, and MCCB test scores as recommended for the MCCB (Nuechterlein & Green, Reference Nuechterlein and Green2016).

Results

Sample characteristics and treatment participation

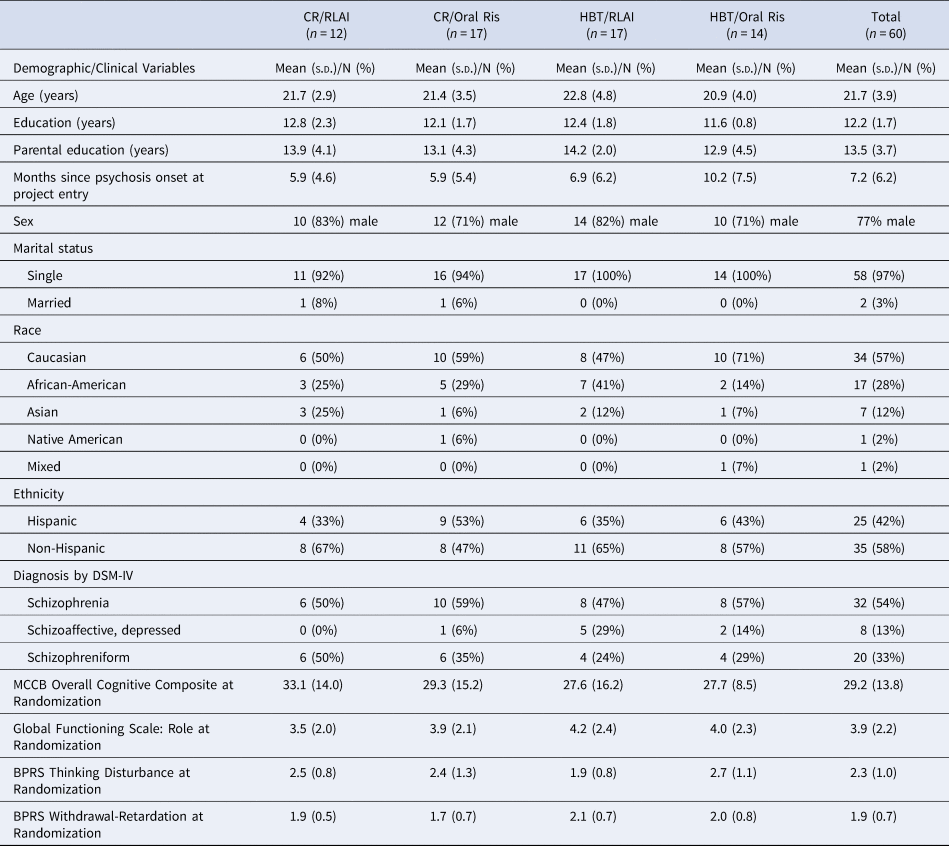

As shown in Table 1, the patients were typical of first-episode psychosis samples in age, education, and sex distribution. Their DSM-IV diagnostic distribution was 54% schizophrenia, 33% schizophreniform, and 13% schizoaffective, depressed. This sample is very early in the course of their psychotic disorder, with mean lifetime duration of psychosis of only 7.2 months at project entry and 13.0 months at randomization. None of the differences in demographic or clinical characteristics in Table 1 was significant across the four treatment groups. Cognitive and work/school functioning at baseline did not differ significantly across the groups.

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients in each of four treatment conditions

Note. MCCB = MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery. BPRS = Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. BPRS factor scores used the Overall, Hollister, and Pichot (Reference Overall, Hollister and Pichot1967) factor structure (Overall et al. Reference Overall, Hollister and Pichot1967).

Only four patients were lost to follow-up after randomization (see Fig. 1). Three refused all psychiatric treatment and one transferred to a private psychiatrist. All available follow-up data were used in each analysis with no minimum number of completed treatment sessions. Outcome data were included even if patients were switched from the randomized medication to a different second-generation oral antipsychotic before the end of 12 months (2 CR-LAI, 2 CR-Oral, 4 HBT-LAI, 8 HBT-Oral). Number of group sessions attended did not differ between CR and HBT sessions (in 12 months, patients attended 52.9 (s.d. = 12.5) CR sessions v. 55.7 (s.d. = 12.7) HBT sessions, t 58 = −0.88, p = .39). Adverse effects of the medication conditions are summarized in online Supplementary Table 2.

Cognition

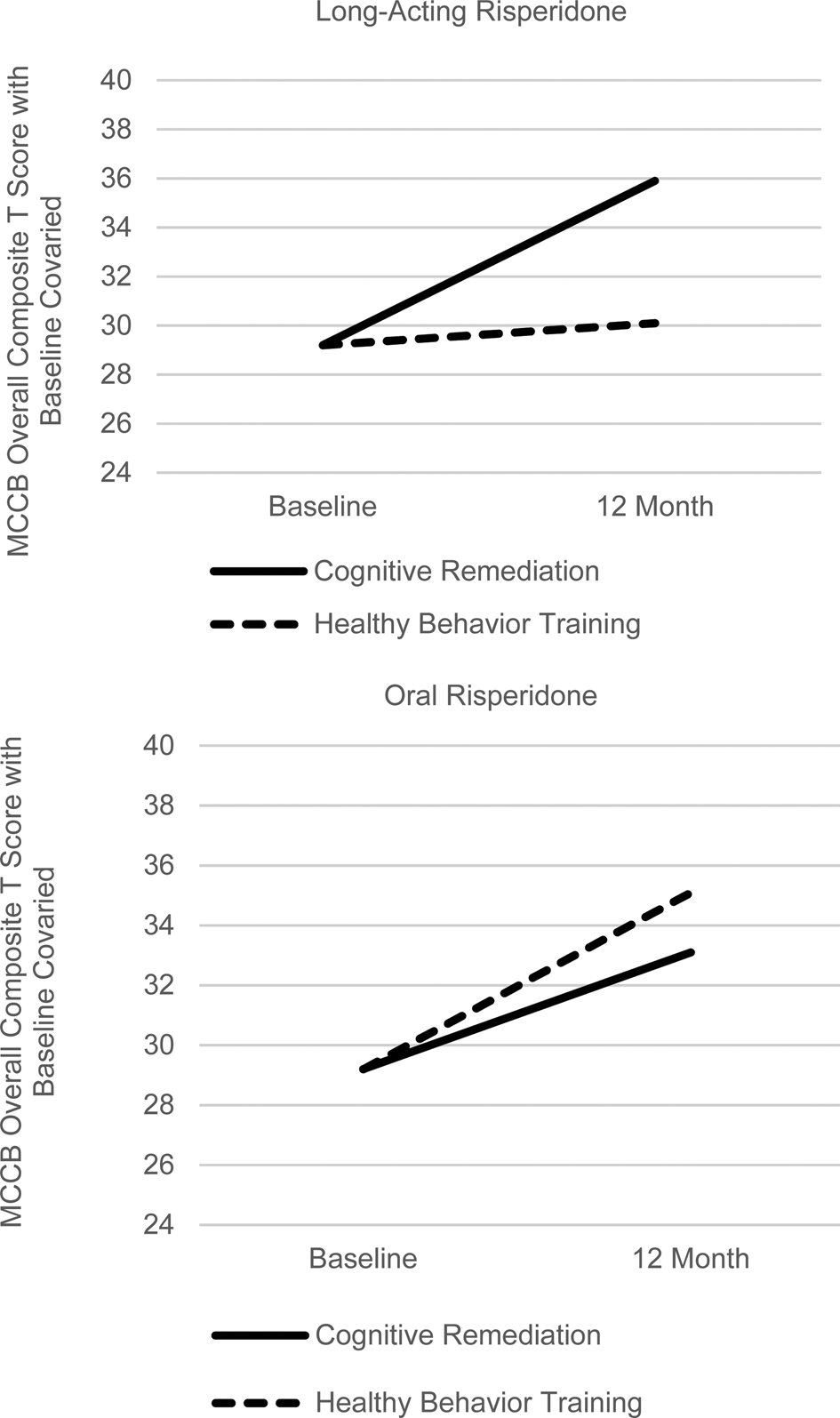

For the MCCB Overall Composite T score, a 2 (LAI-Oral) × 2 (CR-HBT) × Time repeated measures ANCOVA with baseline covaried for the initial 6 months of treatment indicated that the LAI-Oral × Time effect approached a medium effect size but was not significant (F 1,51 = 2.22, p = 0.14, Cohen's f = 0.21, 95% CI for difference in gain −0.45 to 3.07 T scores). (Cohen's d = twice Cohen's f for comparison of two treatments (Cohen, Reference Cohen1988).) The 2 (LAI-Oral) × 2 (CR-HBT) repeated measures ANCOVA from baseline to the 12-month end of treatment yielded a significant LAI-Oral × CR-HBT × Time interaction (F 1,51 = 4.78, p = 0.03, Cohen's f = 0.31). As shown in Fig. 2 (and online Supplementary Figure 1 for raw data), this interaction of medium effect size is due to the presence of a substantially larger cognitive gain with CR than for HBT for patients in the LAI risperidone condition (6.7 v. 0.9 T scores), but no differential gain for CR v. HBT in the oral risperidone condition (3.9 v. 5.9 T scores). Thus, the use of LAI antipsychotic medication facilitated the differential impact of cognitive training. To determine whether psychotic relapses were influencing the impact of LAI medication on cognition, we added relapse as a covariate to the primary 12-month analyses. Despite the fact that psychotic relapses were significantly reduced by LAI v. oral risperidone (2 of 28 v. 10 of 28, χ2 = 6.79, df = 1, p = 0.009), covarying their impact did not alter the significant LAI-Oral × CR-HBT × Time interaction (F 1,50 = 5.51, p = 0.02, Cohen's f = 0.33). Thus, decreasing relapses does not appear to be the path for LAI facilitation of the cognitive training effect.

Fig. 2. Differential 12-month Cognitive Gains in Cognitive Training v. Healthy Behavior Training as a Function of Long-Acting Injectable v. Oral Risperidone (Significant 3-Way Interaction with baseline cognition covaried, F 1,51 = 4.78, p = 0.03, Cohen's f = 0.31).

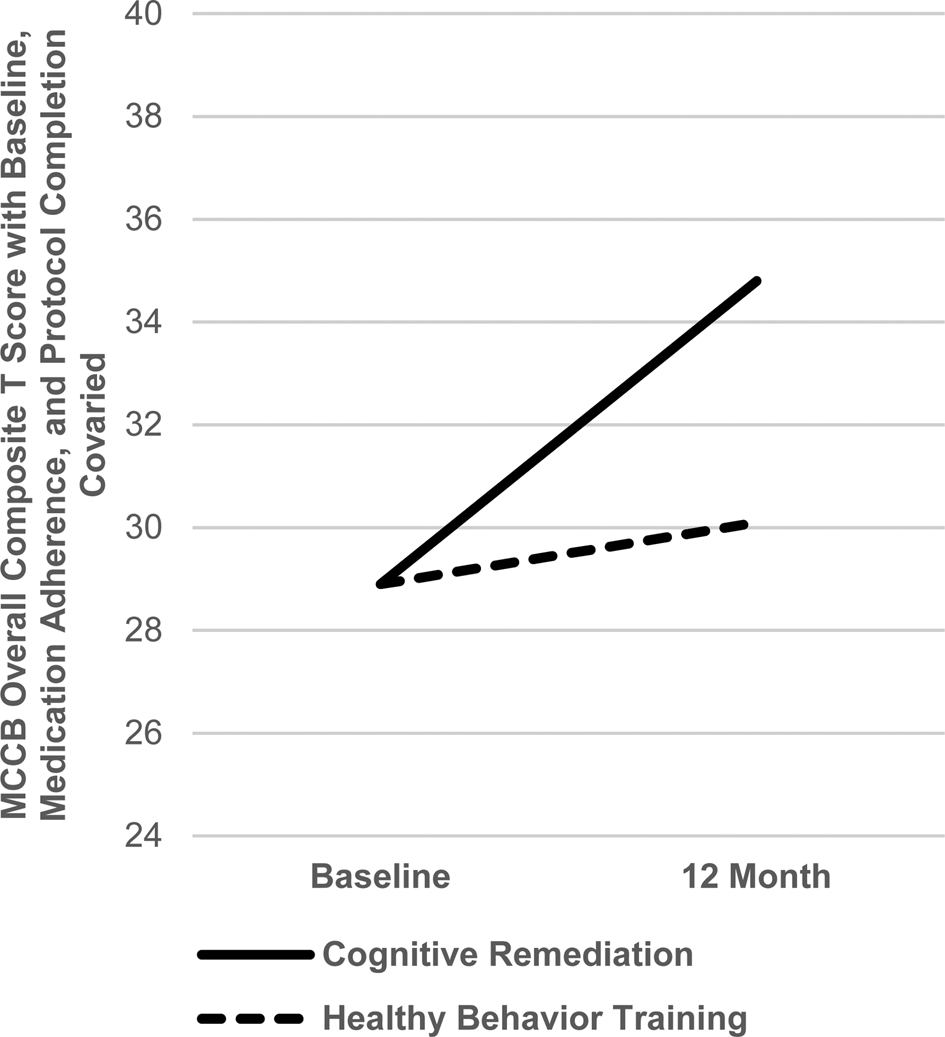

LAI risperidone led to substantially better medication adherence than oral risperidone (mean nonadherence of 1.03 v. 2.00, t 19.2 unequal variance = 6.03, p < 0.001). A wide range of nonadherence (1.1–4.1) was present in the oral condition. The dimensional measure of medication adherence showed that better risperidone medication adherence, across medication groups, was significantly related to larger gains in the MCCB Overall Composite score in the first 6 months (r = .35, p < 0.03). To further examine the effect of cognitive training after medication adherence is accounted for, the CR v. HBT impact over the full 12-month period was evaluated in a repeated measures ANCOVA covarying for the dimensional medication adherence index, finishing 12 months in the medication protocol, and baseline cognitive score. The CR-HBT × Time effect on MCCB Overall Composite T score was significant (F 1,40 = 5.28, p = 0.03, f = 0.36), with CR leading to a 5.8 T score gain compared to 1.2 for HBT, a medium to large effect size (see Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Differential 12-month Cognitive Gains in Cognitive Training v. Healthy Behavior Training after Covarying for Medication Adherence, Completion of the Medication Protocol and Baseline Cognition (F 1,40 = 5.28, p = 0.03, Cohen's f = .36).

Baseline MCCB Overall Composite score was not significantly predictive of the amount of cognitive gain at 6 months (r = 0.21, p = 0.12) or 12 months (r = −0.04, p = 0.78) for the entire sample or within treatment groups.

Means and SEs for the MCCB Overall Composite Score T scores for all four treatment groups are shown in Table 2. For completeness, the individual domain T scores are also provided.

Table 2. MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery (MCCB) T Scores for each of four treatment groups

a F for 3-way interaction between LAI v. Oral Risperidone, CR v. HBT, and Baseline v. 12 months with baseline covaried.

Work/school global functioning

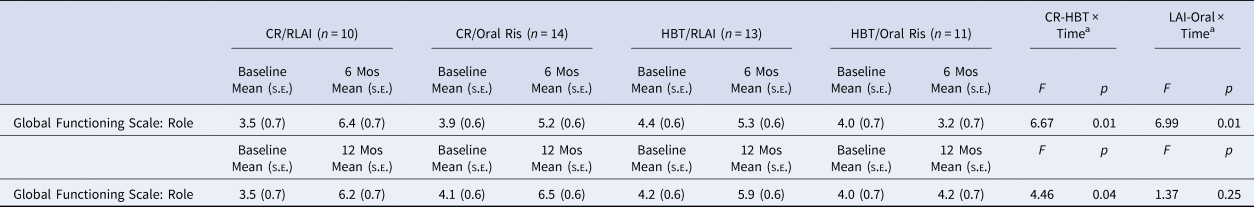

Table 3 provides means and SEs for ratings on the Global Functioning Scale: Role, the primary work/school outcome measure. A repeated measures ANCOVA for the Global Functioning Scale: Role rating with baseline covaried for the first 6 months of more intensive intervention yielded significant LAI-Oral × Time (F1,43 = 6.99, p = 0.01, f = 0.40) and CR-HBT × Time (F 1,43 = 6.67, p = 0.01, f = 0.39) interactions, large effect sizes. LAI led to an improvement of 1.9 compared to 0.2 for Oral risperidone. CR led to a gain of 1.9 v. 0.2 for HBT.

Table 3. Work/School Functioning (Global Functioning Scale: Role) at 6 and 12 months for each of the four treatment groups

a With baseline rating of functioning covaried.

For the full 12-month repeated measures ANCOVA for the Global Functioning Scale: Role with baseline covaried, the CR-HBT × Time interaction was again significant (F 1,43 = 4.46, p = 0.04, f = .32) but the LAI-Oral × Time interaction was not. CR led to the improvement of 2.4 compared to 1.0 for HBT.

The 12-month MCCB Overall Composite Score gain was found to be significantly correlated with the 12-month improvement in the Global Functioning Scale: Role (r = 0.28, p < 0.05). Baseline ratings on the Global Functioning Scale: Role were predictive of the work/school functioning gain over 6 months (r = −0.57, p = 0.001) and 12 months (r = −0.53, p = 0.001) across groups and similarly within treatment groups. Thus, the largest improvements in work/school functioning occurred in those patients with the lowest initial levels.

Duration of work or school

The modified work section of the Social Adjustment Scale was used to measure the total number of weeks in school or competitive work for 12 months. Repeated measures ANOVA revealed significant effects for LAI-Oral (F 1,52 = 4.25, p < 0.05, f = 0.29) and CR-HBT (F 1,52 = 6.31, p < 0.02, f = .35). The mean number of weeks in school or competitive work was 29.9 for LAI compared to 19.3 for Oral risperidone. CR led to 31.1 weeks v. 18.1 weeks for HBT.

Discussion

In this RCT, we examined the impact of antipsychotic medication adherence and of cognitive remediation, in the context of a psychosocial rehabilitation program, with schizophrenia patients whose mean time since the first onset of psychosis was only 7 months at project entry and 13 months at randomization. Both medication adherence and cognitive remediation were found to significantly improve cognitive performance and work/school functioning. The impact of medication adherence on cognition was clearest in the first 6 months after randomization when a continuous index of medication adherence was used. For work/school functioning, LAI risperidone was superior to oral risperidone for 6-month global functioning (large effect of f = .40), and the total number of weeks in work or school over 12 months (f = .29) Thus, LAI antipsychotic effects and their associated higher medication adherence levels appear to have a clearer advantage for cognition and for work/school functioning after a first psychotic episode than in later phases of schizophrenia (Keefe & Harvey, Reference Keefe and Harvey2012; Woodward, Purdon, Meltzer, & Zald, Reference Woodward, Purdon, Meltzer and Zald2005).

The synergistic impact of LAI antipsychotic medication and cognitive training was evident in a significant interaction in which the advantage of CR over HBT was evident only in the LAI medication condition. When medication adherence was covaried, CR was again found to lead to significantly greater cognitive gains by 12 months than HBT. The cognitive gain was substantially greater for CR than for HBT (5.8 v. 1.2 T scores on the MCCB Overall Composite score), yielding a medium to large effect size (f = 0.36). This effect size, equivalent to Cohen's d = 0.72, is larger than in most studies of the early phase of schizophrenia (Revell et al., Reference Revell, Neill, Harte, Khan and Drake2015), but prior studies did not control for medication adherence effects that might partially obscure the cognitive training effect.

CR also was superior to HBT in improving work/school functioning. Significant differential improvements were evident at 6 and 12 months for the Global Functioning Scale: Role rating and for the total number of weeks in work or school over 12 months, all with medium to large effect sizes (f = 0.39, 0.32, and 0.35, respectively, or d = 0.78, 0.64, and 0.70). These effect sizes are substantially larger than the standardized mean difference (similar to Cohen's d) of 0.18 that the Revell et al. (Reference Revell, Neill, Harte, Khan and Drake2015) meta-analysis determined was typical in prior studies of early schizophrenia. The current study used CR over 12 months rather than the 2–3 months typical of prior studies and included a Bridging Group to facilitate generalization to everyday life. All patients were provided Individual Placement and Support, which provides an active rehabilitative context that has been associated with larger CR effects (Wykes et al., Reference Wykes, Huddy, Cellard, McGurk and Czobor2011). The CR focused on cognitive domains ranging from basic attentional and processing speed tasks to complex life-like problem-solving tasks, which might enhance transfer to everyday situations (Nuechterlein et al., Reference Nuechterlein, Ventura, Subotnik, Hayata, Medalia and Bell2014). The significant correlation between cognitive improvement and work/school functional improvement is consistent with the view that at least part of the impact on functional outcome was related to cognitive gains.

Limitations of the current study include moderate sample size, the lack of blind outcome raters, some missing medication adherence data, and the controlled academic setting. The sample size was limited by the restriction to the initial period of schizophrenia, which was critical to study goals; a multi-site study would be needed to substantially increase the sample size and would be an important replication of these initial findings. The therapists who rated work/school functioning were not blind to treatment condition but did have the advantage of interacting regularly with patients, family members, and employers/teachers to obtain relevant information. Ratings of medication adherence were missing for patients who discontinued randomized medication early, so supplemental analyses using that dimensional rating included somewhat fewer subjects. The academic setting of the clinic allowed a rigorous 12-month RCT with a 2 × 2 design to be conducted, but generalization of the demonstrated effects to a typical community clinic cannot be guaranteed without further research. The low dropout rate is likely due to the dedicated staff of this setting, so the extension to a community clinic setting is an important step. This study shows the potential for larger effects of medication adherence and cognitive remediation on cognition and work/school functioning after a first psychotic episode than in prior studies of the early phase of schizophrenia, but transfer to other settings needs to be tested. When a consensus on criteria for functional recovery in schizophrenia is reached (Harvey & Bellack, Reference Harvey and Bellack2009), it would be useful for future research to evaluate the impact of this combination of treatments on functional recovery.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720003335

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of the dedicated UCLA Aftercare Research Program case managers Kimberly Baldwin, M.F.T., Rosemary Collier, M.A., Nicole R. DeTore, M.A., and Yurika Sturdevant, Psy.D. This research was supported by the NIMH (K.H.N., R01 MH037705 and K.H.N., P50 MH066286) (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00333177) and supplementary funding and medication by Janssen Scientific Affairs, L.L.C. (K.H.N., investigator-initiated study RIS-NAP-4009). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institutes of Health, or Janssen Scientific Affairs, L.L.C.

Conflicts of interest

Dr Nuechterlein reports medication and supplemental research grant support from Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC., and has served as a consultant to Astellas, Genentech, Janssen, Medincell, Otsuka, Takeda, and Teva. He is an officer in the nonprofit company, MATRICS Assessment, Inc., which publishes the MCCB, but receives no financial compensation. Dr Ventura has received funding from Brain Plasticity, Inc., Genentech, Inc., and Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, and has served as a consultant to Boehringer-Ingelheim, GmbH, and Brain Plasticity, Inc. Dr Subotnik has received lecture honoraria from Janssen. Other authors report no potential conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.