Introduction

Cannabis is the most commonly used illicit drug globally. It is estimated that approximately 3.8% of the global population (188 million people) aged 15–64 used cannabis in the last year (UNODC, 2019). Cannabis use is especially prevalent in adolescents and young adults, with 18% of European 15–24 year olds, compared to 7.4% of 25–64 year olds having tried cannabis in the past year (European Monitoring Centre for Drugs & Drug Addiction, 2019). Many people who use cannabis do so infrequently, and without major problems. However, epidemiological studies suggest that approximately 3 in 10 users go on to develop a problematic pattern of use characterised by continued use despite persistent adverse consequences (Hasin et al., Reference Hasin, Saha, Kerridge, Goldstein, Chou, Zhang and Grant2015; Marel et al., Reference Marel, Sunderland, Mills, Slade, Teesson and Chapman2019). Cannabis use disorder (CUD) refers to recurrent use of cannabis despite negative impact on the individual's life, causing clinically significant impairment or distress (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). CUD replaced earlier diagnostic criteria of problematic use represented in DSM-IV-TR as separate diagnoses for ‘cannabis abuse’ and ‘cannabis dependence’ which remain widely used in the literature at present.

New medical and recreational cannabis laws, as well as increased discourse about cannabis and cannabinoids as medical products, have the potential to influence public perceptions of cannabis including the risks associated with its use. This could influence access to cannabis, as well as acceptability of treatment. However, despite public perception of the harmfulness of using cannabis decreasing over recent years (Hasin, Reference Hasin2018), the role of changing cannabis laws in this trend is unclear (Keyes et al., Reference Keyes, Wall, Cerdá, Schulenberg, O'Malley, Galea and Hasin2016), and the impact this may have on demand of treatment is also uncertain (Budney, Sofis, & Borodovsky, Reference Budney, Sofis and Borodovsky2019).

Accumulating evidence suggests that CUDs are common and they often go untreated (Hasin et al., Reference Hasin, Kerridge, Saha, Huang, Pickering, Smith and Grant2016; Kerridge et al., Reference Kerridge, Mauro, Chou, Saha, Pickering, Fan and Hasin2017; Khan et al., Reference Khan, Secades-Villa, Okuda, Wang, Pérez-Fuentes, Kerridge and Blanco2013). It is estimated that there are 22 million people worldwide with a CUD, comparable to an estimated 27 million for opioid use disorders (Degenhardt et al., Reference Degenhardt, Charlson, Ferrari, Santomauro, Erskine, Mantilla-Herrara and Vos2018), highlighting a clear clinical need for effective treatments. Regular cannabis use is associated with various negative mental health outcomes such as psychosis, anxiety and depression (Leadbeater, Ames, & Linden-Carmichael, Reference Leadbeater, Ames and Linden-Carmichael2019; Patton et al., Reference Patton, Coffey, Carlin, Degenhardt, Lynskey and Hall2002). Comorbidity between problematic cannabis use and other mental health disorders can create significant challenges for patients and treatment providers.

In this narrative review, we discuss state-of-the-art clinical evidence on the treatment of CUDs. We begin by reviewing the latest evidence for psychosocial and pharmacological treatments. Next, we discuss treatments targeting CUDs comorbid with psychosis. This is a particularly important treatment need, given cannabis is used by an estimated 33.7% of people with first-episode psychosis (Myles, Myles, & Large, Reference Myles, Myles and Large2016) and continued cannabis use is consistently associated with poorer clinical outcomes including longer hospital admissions, more severe positive symptoms (Schoeler et al., Reference Schoeler, Monk, Sami, Klamerus, Foglia, Brown and Bhattacharyya2016) and poor medication adherence leading to relapse (Schoeler et al., Reference Schoeler, Petros, Di Forti, Klamerus, Foglia, Murray and Bhattacharyya2017). Finally, we focus on treatments targeting CUD when comorbid with anxiety and depression. Anxiety and depression are common mental disorders, are highly comorbid with CUD (Hasin et al., Reference Hasin, Kerridge, Saha, Huang, Pickering, Smith and Grant2016) and can influence treatment outcomes. For example, anxiety is associated with greater withdrawal symptom severity from cannabis use (Buckner, Walukevich, Zvolensky, & Gallagher, Reference Buckner, Walukevich, Zvolensky and Gallagher2017) and depression is associated with lower likelihood of cannabis abstinence during a cessation attempt (Tomko et al., Reference Tomko, Baker, Hood, Gilmore, McClure, Squeglia and Gray2020).

Search strategy and selection criteria

Articles for this review were obtained by searching PubMed, PsychInfo, Google Scholar, Embase and Medline databases and the Cochrane Review database for key terms ‘Cannabis’, ‘THC’, ‘CUD’, ‘Cannabis use disorder’, ‘Psychosis’, ‘Anxiety’, ‘Depression’, ‘Treatment’ and ‘Dual Diagnosis’ from inception up to 24 February 2020. Additional articles were obtained from reference lists of existing papers and reviews. We searched the relevant grey literature (UNODC and EMCDDA) for the most up to date information on CUD internationally. RL ran the literature searches and consulted all authors on the inclusion of studies. We included studies that investigated psychosocial or pharmacological treatment options for CUD, including samples with and without comorbidities. Most of the included studies were randomised control trials (RCTs), although other experimental designs were included where RCTs had not been conducted or were inconclusive. Studies with both inpatient and outpatient designs were eligible. Trials were prioritised for inclusion based on methodology (such as large multisite RCTs) and novelty to the field. Where several trials of the same intervention had been conducted with converging results, we discuss the key trials. Studies predominantly used DSM-IV criteria, although studies that measured CUD in other ways (ICD, CUDIT and DSM-5) were included.

Treatment of cannabis use disorders

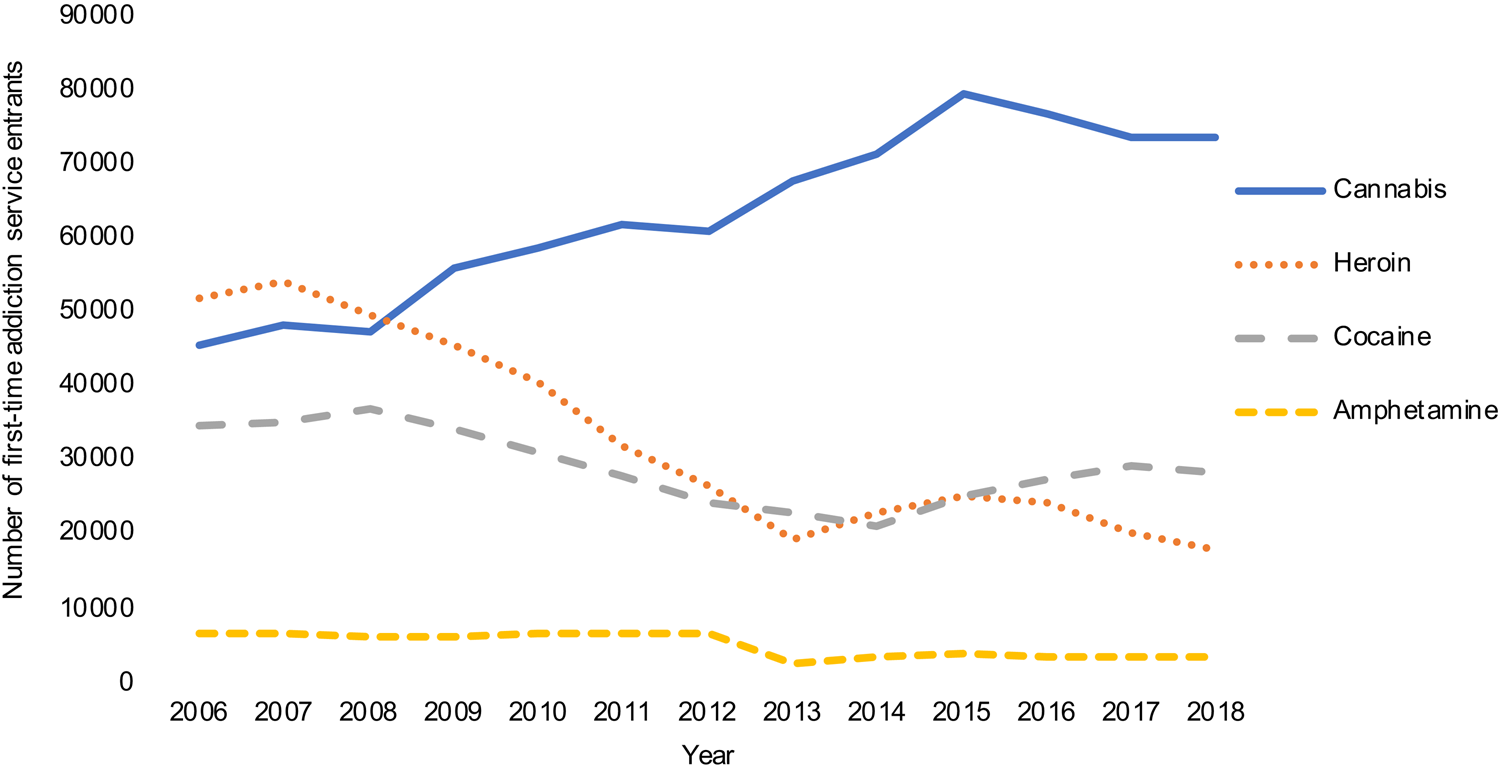

Treatment demand for cannabis use is increasing globally in every region except for Africa (UNODC, 2019). In Europe, 155 000 individuals entered treatment for problems related to cannabis in 2017, with over half entering treatment for the first time (European Monitoring Centre for Drugs & Drug Addiction, 2019; Montanari, Guarita, Mounteney, Zipfel, & Simon, Reference Montanari, Guarita, Mounteney, Zipfel and Simon2017). A possible contributor to these changes is the increase in cannabis potency in recent decades (Freeman et al., Reference Freeman, Craft, Wilson, Stylianou, ElSohly, Di Forti and Lynskey2020a) which has been associated with elevated treatment admissions for CUDs (Freeman et al., Reference Freeman, van der Pol, Kuijpers, Wisselink, Das, Rigter and Niesink2018). In fact, cannabis is now responsible for more first time admissions than any other drug in Europe (Fig. 1; European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, 2019). A typical client entering drug treatment for cannabis initiates use at age 17, enters treatment at 25 and uses cannabis 5.3 days per week at treatment entry.

Fig. 1. Number of first time entrants to addiction services in Europe by primary drug. Data from the EMCDDA.

Although these treatment data are indicative of the extent of problematic use in the population, prevalence of CUD is much greater and it is estimated that over 85% of individuals with lifetime CUD do not seek treatment (Hasin et al., Reference Hasin, Kerridge, Saha, Huang, Pickering, Smith and Grant2016). In Europe, there is considerable variation by country in the estimates of unmet cannabis treatment needs. Although treatment provision is high in some countries (e.g. Germany and Norway) where one in 10 daily users receive treatment, it is low in others (including Italy, Spain and France) where one to three of every 100 daily users receive treatment (Schettino, Leuschner, Kasten, Tossmann, & Hoch, Reference Schettino, Leuschner, Kasten, Tossmann and Hoch2015). In a large survey of adults with CUD in the USA, 10.28% had received drug treatment of any kind in the past year, with only 7.81% having received cannabis-specific treatment (Wu, Zhu, Mannelli, & Swartz, Reference Wu, Zhu, Mannelli and Swartz2017).

Psychosocial treatments

There is good evidence that psychosocial treatments can be effective for the treatment of CUDs (Table 1). Treatment options are often not developed specifically for use in CUD and many have been adapted from existing substance use treatments (Schettino et al., Reference Schettino, Leuschner, Kasten, Tossmann and Hoch2015). Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and motivational enhancement therapy (MET) can reduce frequency and intensity of cannabis use as well as symptoms of dependence, in comparison with inactive control, and can be delivered in combination (Gates, Sabioni, Copeland, Le Foll, & Gowing, Reference Gates, Sabioni, Copeland, Le Foll and Gowing2016). For example, an RCT of 10-week combined CBT, MET and problem solving training treatment (n = 149) compared to delayed treatment control (n = 130) was conducted at 11 outpatient treatment centres in Germany (Hoch et al., Reference Hoch, Bühringer, Pixa, Dittmer, Henker, Seifert and Wittchen2014). Compared to control, treatment improved rates of self-reported abstinence and urinary-verified abstinence at post-treatment, although reported abstinence rates decreased at 6-month follow-up in the treatment group. Treatment also impacted the number of ICD-10 cannabis dependence criteria met at post-treatment, however rates of dependence or abuse were low in the sample at baseline (56.3% and 8.6%, respectively).

Table 1. Study design and primary endpoint data for psychosocial interventions for CUD

Psychotherapies are appropriate in adolescent samples, and inclusion of the patient's family in treatment may be particularly effective. For example, an international multi-site RCT (Rigter et al., Reference Rigter, Henderson, Pelc, Tossmann, Phan, Hendriks and Rowe2013) found that a 6 month programme of multidimensional family therapy (n = 212) reduced cannabis dependence in adolescents better than individual psychotherapy (n = 238) over the same time period, with a significantly greater shift from dependence to abuse or no CUD in the family therapy group.

Brief versions of MET have also been investigated, primarily in school based settings, to ascertain whether psychosocial treatment can be employed without lengthy and intensive treatment intervention (Walker et al., Reference Walker, Stephens, Roffman, DeMarce, Lozano, Towe and Berg2011). In one such RCT from the USA, adolescents received two sessions of MET, and were then randomly assigned to a motivational check in (n = 128) or assessment-only check in (n = 124), with extra CBT sessions offered but not enforced (Walker et al., Reference Walker, Stephens, Blevins, Banes, Matthews and Roffman2016). The two sessions of MET reduced cannabis use under both conditions, with the motivation check-in group showing a larger reduction in days of use and fewer symptoms at 6-months, however this was not sustained at 9- or 12-month follow-up.

Evidence suggests that adding contingency management (CM) of monetary incentives for abstinence outcomes to combined CBT + MET can increase the likelihood of reducing cannabis frequency and achieving abstinence into longer term follow-ups (Kadden, Litt, Kabela-Cormier, & Petry, Reference Kadden, Litt, Kabela-Cormier and Petry2007). In fact, evidence from RCTs in the USA suggests that CM alone can reduce cannabis use more effectively than CBT during the treatment period. For example, Budney, Moore, Rocha, and Higgins (Reference Budney, Moore, Rocha and Higgins2006) found the average number of weeks of continuous abstinence during treatment were significantly superior in a CM-only condition (n = 30) than CBT (n = 30), and adding CBT to CM did not offer any additional benefit (n = 30). However, the analysis of continuous abstinence was underpowered and therefore potentially important differences between groups may not have been detected. This was mirrored in findings by Kadden et al. (Reference Kadden, Litt, Kabela-Cormier and Petry2007) who found a CM-only condition to have superior rates of abstinence at post-treatment to MET–CBT in a large (n = 240), 9-week RCT from the USA, although abstinence rates then declined after 5 months. Combined MET–CBT and CM yielded the longest periods of continuous abstinence during the follow-up year and resulted in the greatest proportion of individuals abstinent at 11- and 14-month follow-up.

Finally, there is evidence of small treatment effects for digital interventions on reducing cannabis use (Hoch, Preuss, Ferri, & Simon, Reference Hoch, Preuss, Ferri and Simon2016). The most promising results come from an RCT conducted in Germany (Tossmann, Jonas, Tensil, Lang, & Strüber, Reference Tossmann, Jonas, Tensil, Lang and Strüber2011) that employed online discussion with a trained psychotherapist, including weekly personalised feedback based on CBT (n = 863), compared to waiting list (n = 429). The treatment group showed a greater reduction in days of use over the last 30 days compared to waiting list as well as reduced quantity of cannabis used at follow-up conducted 3-months after enrolment on the programme. However, these analyses were not sufficiently powered due to low engagement and high dropout rates. Preliminary evidence from an RCT conducted in the USA showed that a 4-week text-delivered treatment reduced the proportion of the sample reporting cannabis-related relationship problems (n = 51) significantly more than an assessment-only control (n = 50). However, there was no reduction in frequency of cannabis use (Mason et al., Reference Mason, Zaharakis, Moore, Brown, Garcia, Seibers and Stephens2018). Furthermore, retention was high with 96% of participants completing 3-month follow-up. Digital interventions so far have produced mixed findings, but given their potential for tackling barriers to treatment engagement, larger trials assessing their reduction in cannabis use as well as diversity of population they can reach are warranted. Further digital interventions such as smartphone apps show promise in this area (Albertella, Gibson, Rooke, Norberg, & Copeland, Reference Albertella, Gibson, Rooke, Norberg and Copeland2019) and have the potential to reach the substantial number of people who do not seek in person treatment for CUDs at present.

Pharmacological treatments

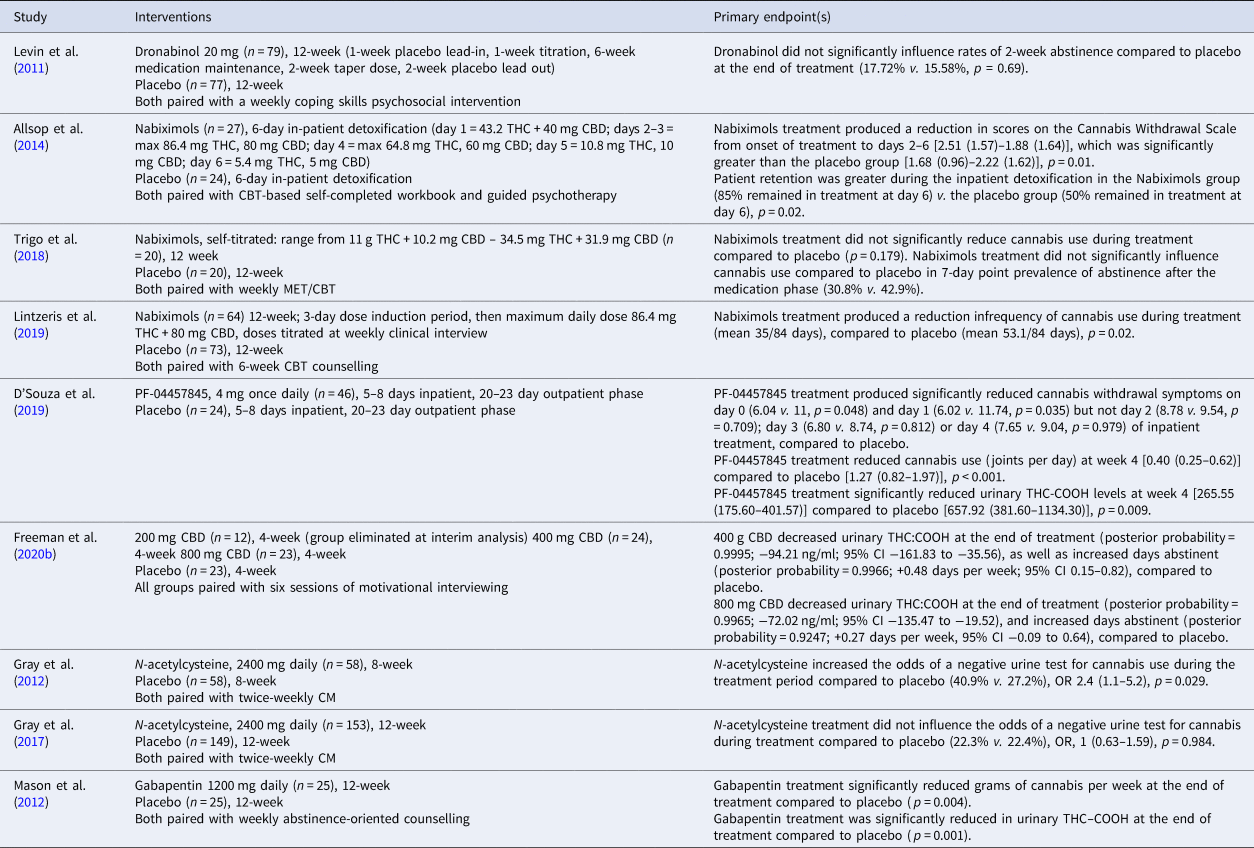

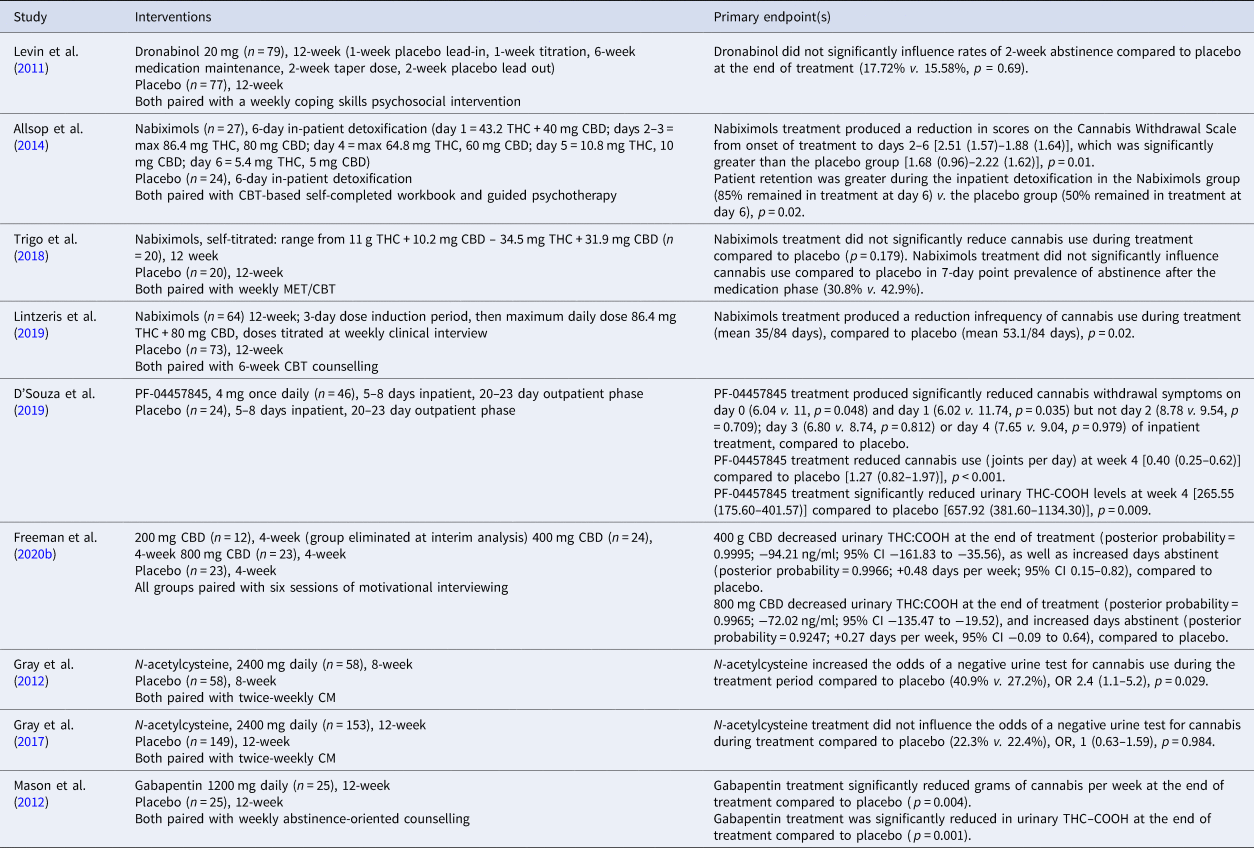

A 2019 Cochrane review concluded that there were no high-quality indications of an effective pharmacological treatment for CUD based on available evidence (Nielsen, Gowing, Sabioni, & Le Foll, Reference Nielsen, Gowing, Sabioni and Le Foll2019) (Table 2). Since the publication of this review there have been several new trials of pharmacological treatment of CUDs (D'Souza et al., Reference D'Souza, Cortes-Briones, Creatura, Bluez, Thurnauer, Deaso and Skosnik2019; Freeman et al., Reference Freeman, Hindocha, Baio, Shaban, Thomas, Astbury and Curran2020b; Lintzeris et al., Reference Lintzeris, Bhardwaj, Mills, Dunlop, Copeland and McGregor2019). Moreover, the Cochrane review based its recommendations on abstinence achieved at the end of treatment. However, expert consensus recommends that sustained abstinence should not be considered the primary outcome for all clinical trials of CUD (Loflin et al., Reference Loflin, Kiluk, Huestis, Aklin, Budney, Carroll and Strain2020).

Table 2. Study design and primary endpoint data for pharmacological interventions for CUD

Substitution cannabinoid treatments

Several studies have investigated the effects of Dronabinol [synthetic delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) THC] or Nabiximols (THC and CBD at 1:1 ratio) for the treatment of CUD and/or cannabis withdrawal. An RCT conducted in the USA (Levin et al., Reference Levin, Mariani, Brooks, Pavlicova, Cheng and Nunes2011) found that 40 mg daily Dronabinol (treatment n = 70, placebo n = 77) in combination with MET was superior to placebo at reducing severity of withdrawal symptoms but not rates of 2-week abstinence. Days of cannabis use measured via an extensive TLFB method was also not significantly different between Dronabinol and placebo. Additionally, a two-site inpatient detoxification trial in Australia (Allsop et al., Reference Allsop, Copeland, Lintzeris, Dunlop, Montebello, Sadler and McGregor2014; treatment n = 27, placebo n = 24) of 6 days Nabiximols combined with MET/CBT was found to reduce withdrawal, and improve treatment retention, but was not associated with greater reduction in cannabis use. Furthermore, a pilot, outpatient RCT in Canada (Trigo et al., Reference Trigo, Soliman, Quilty, Fischer, Rehm, Selby and Le Foll2018) found no significant difference in frequency of cannabis use or withdrawal symptoms for 12-week treatment of flexible Nabiximols use combined with weekly MET/CBT (n = 20) compared to placebo and MET/CBT (n = 20). The Nabiximols group reduced their tobacco use over the trial. A multi-site, outpatient RCT conducted in Australia (Lintzeris et al., Reference Lintzeris, Bhardwaj, Mills, Dunlop, Copeland and McGregor2019) tested 12-week flexible Nabiximols treatment with six sessions of CBT (n = 64) compared to placebo and six sessions of CBT (n = 73). Contrasting with previous findings, Nabiximols reduced frequency of cannabis use during the trial compared to placebo but did not significantly reduce cannabis withdrawal over placebo. These results were sustained at 12-week follow-up (Lintzeris et al., Reference Lintzeris, Mills, Dunlop, Copeland, Mcgregor, Bruno and Bhardwaj2020). This study monitored nicotine and alcohol dependence over the treatment period and found no change over time or any group differences. Overall, evidence suggests that substitution treatments containing THC typically reduce withdrawal symptoms but evidence for their effectiveness at reducing cannabis use is mixed and may depend on the setting and duration of treatment.

Non-substitution cannabinoid treatments

Trials have also tested alternative pharmacological treatments acting on the endocannabinoid system (Parsons & Hurd, Reference Parsons and Hurd2015). A phase II RCT involving 5 day enforced-abstinence followed by 4-week treatment with the FAAH inhibitor PF-04457845 (n = 46; D'Souza et al. Reference D'Souza, Cortes-Briones, Creatura, Bluez, Thurnauer, Deaso and Skosnik2019) compared to placebo (n = 24) found reductions in self-reported use of cannabis at the end of treatment, and THC:COOH concentrations, as well as reduced cannabis withdrawal symptoms on the first and second day of enforced abstinence. As PF-04457845 did not have sufficient safety data in females at the time of this study, only male participants were included. These safety data are now available, and a subsequent phase III trial (n = 273) including males and females is currently underway. Finally, a phase IIa adaptive Bayesian RCT conducted in the UK (Freeman et al., Reference Freeman, Hindocha, Baio, Shaban, Thomas, Astbury and Curran2020b) tested CBD at daily doses of 200, 400, 800 mg v. placebo for four weeks alongside six sessions of motivational interviewing. CBD was more efficacious than placebo at reducing cannabis at daily doses of 400 or 800 mg (posterior probabilities >0.9) but not 200 mg (posterior probability <0.1). Cannabis use measured via self-report and urinary THC:COOH was reduced compared to placebo (n = 23) following 400 mg (n = 24) and 800 mg (n = 23) CBD. Reductions in cannabis use were maintained up to 24-week follow-up with 400 mg CBD but not 800 mg CBD. These results suggest a possible inverted-U dose–response curve effect of CBD on cannabis use, consistent with CBD effects on anxiety (Zuardi et al., Reference Zuardi, Rodrigues, Silva, Bernardo, Hallak, Guimarães and Crippa2017). Longer follow-ups and RCTs specifically designed to determine efficacy are required to extend these results. Both FAAH inhibitors and CBD can increase concentrations of the endocannabinoid anandamide (D'Souza et al., Reference D'Souza, Cortes-Briones, Creatura, Bluez, Thurnauer, Deaso and Skosnik2019; Leweke et al., Reference Leweke, Piomelli, Pahlisch, Muhl, Gerth, Hoyer and Koethe2012). These non-substitution cannabinoid treatments offer possible strategies to treat CUDs through endocannabinoid system mechanisms, without risk of harm from THC administration.

Other pharmacological treatments

An RCT from the USA investigating N-acetylcysteine added on to CM treatment has shown effectiveness at treating CUD in adolescents (Gray et al., Reference Gray, Carpenter, Baker, DeSantis, Kryway, Hartwell and Brady2012). Those receiving N-acetylcysteine treatment (n = 58) were 2.4 times more likely to submit a negative urinary screen for cannabis use compared to placebo (n = 58). There was no significant difference in change of days with self-reported cannabis use across the trial between groups. Contrasting results were found in a subsequent multi-site RCT of adults with CUD (Gray et al., Reference Gray, Sonne, McClure, Ghitza, Matthews, McRae-Clark and Levin2017) where negative urinary screens were not statistically different between N-acetylcysteine (n = 153) and placebo (n = 149). These treatment effects were not moderated by sex, ethnicity or tobacco smoking status. However, baseline tobacco use was a significant predictor of negative cannabis outcomes in general, with tobacco smokers half as likely to achieve abstinence from cannabis in both groups. These findings illustrate the importance of considering tobacco use in the treatment of CUD.

There is some evidence for the effectiveness of gabapentin in the treatment of CUD from an RCT in the USA (Mason et al., Reference Mason, Crean, Goodell, Light, Quello, Shadan and Rao2012). Gabapentin together with abstinence-oriented counselling demonstrated superiority at 1200 mg/day for 12 weeks (n = 25) over placebo (n = 25), at reducing cannabis use as verified through reduced self-reported grams of cannabis, fewer self-reported days of cannabis use and reduced urinary THC–COOH concentrations as well as lower cannabis withdrawal severity. However, a limitation was high levels of drop out in the trial (n = 18 for Gabapentin; n = 14 for placebo). Moreover, a larger trial (Mason, Reference Mason2017) of Gabapentin 1200 mg/day for 12 weeks (n = 75) did not demonstrate efficacy compared to placebo (n = 75).

In summary, substitution cannabinoid treatments containing THC appear effective at reducing cannabis withdrawal but evidence has been mixed for changes in cannabis use. Other treatments targeting the endocannabinoid system (FAAH inhibition and CBD) and N-acetylcysteine (in adolescents, but not adults) show proof of concept evidence for reducing cannabis use, but require replication in larger trials.

Psychosis

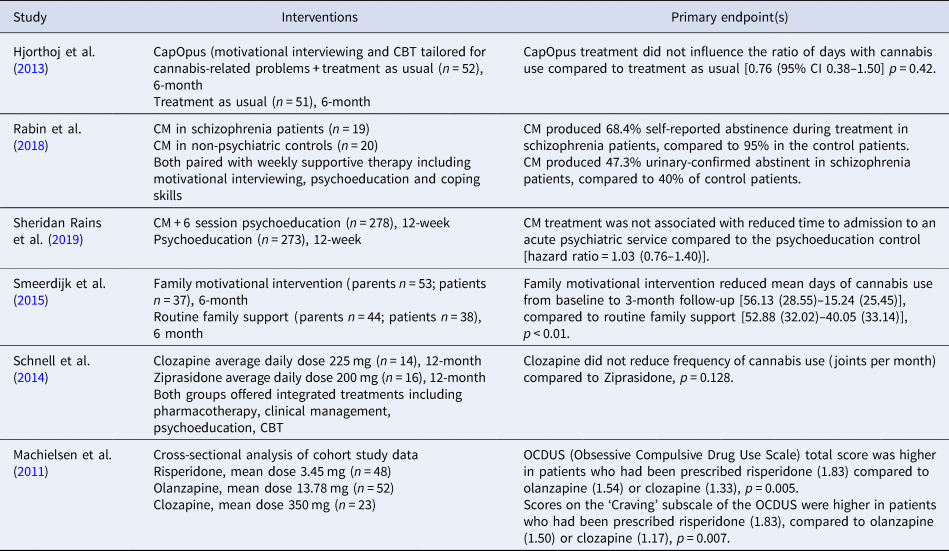

A Cochrane review published in 2014 concluded that there is a lack of good quality evidence for the efficacy of any psychosocial or pharmacological treatment at reducing cannabis use in psychosis (McLoughlin et al., Reference McLoughlin, Pushpa-Rajah, Gillies, Rathbone, Variend, Kalakouti and Kyprianou2014) (Table 3). Studies conducted since the publication of that review have had mixed findings (Rabin et al., Reference Rabin, Kozak, Zakzanis, Remington, Stefan, Budney and George2018; Sheridan Rains et al., Reference Sheridan Rains, Marston, Hinton, Marwaha, Craig, Fowler and Johnson2019; Smeerdijk et a., Reference Smeerdijk, Keet, Van Raaij, Koeter, Linszen, De Haan and Schippers2015). Tailored and time-intensive cannabis-focused treatment plans have not provided better outcomes than treatment as usual (Wisdom, Manuel, & Drake, Reference Wisdom, Manuel and Drake2011). For example, a superiority trial conducted in Denmark using weekly motivational interviewing and CBT targeted specifically at patients with psychosis who continued to use cannabis (n = 52), found similar reductions in cannabis use at the end of treatment and follow-up as treatment as usual (n = 51), targeted only towards psychotic disorder (Hjorthoj et al., Reference Hjorthoj, Fohlmann, Larsen, Gluud, Arendt and Nordentoft2013).

Table 3. Study design and primary endpoint data for targeted interventions for comorbid CUD and psychosis

A small feasibility study of Canadian males found that supportive therapy alongside a $300 payment for 28 day abstinence was associated with 68.4% of patients with CUD and schizophrenia (n = 19), reporting abstinence, compared to 95% of patients with CUD-only (n = 20) reporting abstinence. However, negative urinary screens were only present in 47.3% of patients with schizophrenia, and 40% in CUD-only (Rabin et al., Reference Rabin, Kozak, Zakzanis, Remington, Stefan, Budney and George2018). Replication of these findings has not been achieved in subsequent RCTs to date. A large (n = 551, treatment n = 278), multi-centre RCT from the UK (Sheridan Rains et al., Reference Sheridan Rains, Marston, Hinton, Marwaha, Craig, Fowler and Johnson2019) investigating the addition of a voucher-incentive programme to early intervention psychosis treatment did not find a difference in the primary outcome of time to admission to an acute mental health service, and no difference on self-reported cannabis use at the end of treatment.

Finally, a trial conducted in the Netherlands demonstrated that a family motivational intervention (parents n = 53, patients n = 37) which focuses on establishing a supportive family environment, compared to routine family support (parents n = 44, patients n = 38) was effective at reducing frequency and quantity of cannabis use in adolescent and young adult patients with schizophrenia at 3 month follow-up (Smeerdijk et al., Reference Smeerdijk, Keet, Dekker, van Raaij, Krikke, Koeter and Linszen2012). This was sustained at 15-month follow-up (Smeerdijk et al., Reference Smeerdijk, Keet, Van Raaij, Koeter, Linszen, De Haan and Schippers2015). There were no significant changes from baseline in use of alcohol or any other drugs other than cannabis during this trial.

Overall, RCT data suggest that psychosocial treatments that appear effective in CUD-only patients (including CM) do not appear effective for patients with comorbid psychosis. However, involvement of the family in treatment appears successful in some patients and is a possible strategy for future research. In addition to psychosocial treatments, the effects of digital interventions are currently unclear, but a targeted, self-guided web-based programme is currently being trialled for young people with psychotic experiences and cannabis use in Australia (Hides et al., Reference Hides, Baker, Norberg, Copeland, Quinn, Walter and Kavanagh2020).

Evidence for the role of pharmacological treatments for CUDs in people with psychosis is lacking at present. A systematic review found preliminary evidence that some antipsychotic medications might be effective at reducing both cannabis use and psychotic symptoms (Wilson & Bhattacharyya, Reference Wilson and Bhattacharyya2015). Both clozapine (n = 14) and ziprasidone (n = 16) were associated with significant reduction in cannabis use and psychotic symptoms (PANSS positive), in a pilot study conducted in Germany (Schnell et al., Reference Schnell, Koethe, Krasnianski, Gairing, Schnell, Daumann and Gouzoulis-Mayfrank2014). Further evidence from Machielsen et al. (Reference Machielsen, Beduin, Dekker, Kahn, Linszen, van Os and Myin-Germeys2011) suggests that olanzapine treatment (n = 52) is associated with lower cannabis craving in comparison with risperidone (n = 48) in patients with psychotic disorder and cannabis dependence as measured using the craving subscale of the Obsessive Compulsive Drug Use Scale. However, this comparison used cross-sectional data from a larger study conducted in the Netherlands rather than an RCT design. Altogether, evidence suggests that standard antipsychotic treatment for psychosis may have additional benefits for patients with comorbid CUD. Future research should consider whether any additional treatment options are efficacious to further support these patients. Furthermore, other pharmacological treatments that have been investigated in CUD have not been explored in comorbid psychosis, so their efficacy in these patients is unknown at present.

Pharmacological management of CUD and psychosis should consider interactions between cannabis and prescribed antipsychotic medication (Brzozowska et al., Reference Brzozowska, de Tonnerre, Li, Wang, Boucher, Callaghan and Arnold2017). Such drug–drug interactions may account for poor antipsychotic medication adherence, which mediated the effects of cannabis use on relapse to psychosis in a 2-year prospective observational study (Schoeler et al., Reference Schoeler, Petros, Di Forti, Klamerus, Foglia, Murray and Bhattacharyya2017). Emerging evidence strongly implicates the endocannabinoid system in psychosis (Minichino et al., Reference Minichino, Senior, Brondino, Zhang, Godwlewska, Burnet and Lennox2019) as well as addiction (Curran et al., Reference Curran, Freeman, Mokrysz, Lewis, Morgan and Parsons2016) which presents a promising target for future treatments. Antipsychotic treatments which act on the endocannabinoid system (CBD) have produced favourable outcomes (Leweke et al., Reference Leweke, Piomelli, Pahlisch, Muhl, Gerth, Hoyer and Koethe2012; McGuire et al., Reference McGuire, Robson, Cubala, Vasile, Morrison, Barron and Wright2017). One possible strategy is CBD for the treatment of comorbid CUD and psychosis (Batalla, Janssen, Gangadin, & Bossong, Reference Batalla, Janssen, Gangadin and Bossong2019). Due to the poor efficacy of psychosocial interventions for comorbid CUD and psychosis, and the poor clinical outcomes associated with continued cannabis use in this population, the development of effective pharmacological treatments is an urgent priority.

Anxiety and depression

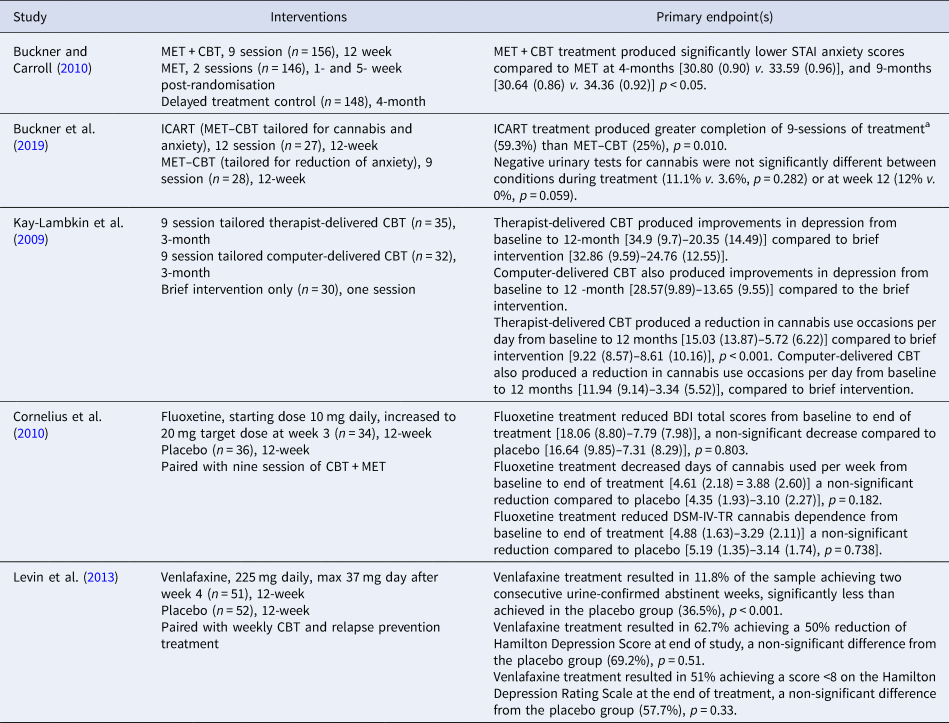

A large multisite RCT in the USA (Buckner & Carroll, Reference Buckner and Carroll2010) reported that nine sessions of CBT tailored to CUD (n = 156) compared to two-session MET alone (n = 146) reduced anxiety and that reduction was correlated with successful reduction in CUD (Table 4). Furthermore, a small pilot trial conducted in the USA combining cannabis-tailored MET–CBT with transdiagnostic anxiety treatment (ICART, n = 27) showed preliminary evidence of increased rates of abstinence at the end of treatment over MET–CBT alone as confirmed using urinalysis (Buckner et al., Reference Buckner, Zvolensky, Ecker, Schmidt, Lewis, Paulus and Bakhshaie2019). Targeted treatments for depression have also been investigated. For example, a study from Australia (Kay-Lambkin, Baker, Lewin, & Carr, Reference Kay-Lambkin, Baker, Lewin and Carr2009) found that motivational interviewing plus CBT treatment tailored for both depressive symptoms and comorbid cannabis use (SHADE, n = 67) resulted in significant overall reductions in cannabis use over 12 months, and reductions in depressive symptoms compared to a brief intervention (n = 97). There is no current evidence for an effective pharmacological treatment for both depression and CUD. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors have been investigated as a treatment for CUD, and have not proven efficacious (McRae-Clark et al., Reference McRae-Clark, Baker, Gray, Killeen, Hartwell and Simonian2016; Weinstein et al., Reference Weinstein, Miller, Bluvstein, Rapoport, Schreiber, Bar-Hamburger and Bloch2014). Moreover, trials investigating fluoxetine and venlafaxine specifically for comorbid depression and CUD, have not found improvement in CUD or depression in comparison with placebo (Cornelius et al., Reference Cornelius, Bukstein, Douaihy, Clark, Chung, Daley and Brown2010; Levin et al., Reference Levin, Mariani, Brooks, Pavlicova, Nunes, Agosti and Carpenter2013).

Table 4. Study design and primary endpoint data for targeted interventions for comorbid CUD and anxiety or depression

a Endpoint chosen as the greatest number of weeks that could be compared due to MET–CBT treatment having fewer sessions than ICART.

Taken together, it appears feasible to target comorbid CUD with anxiety or depression effectively with psychosocial treatment and this should be encouraged. To date, pharmacological treatments specifically targeting CUD comorbid with anxiety or depression have not been successful.

Summary of findings and critical appraisal

Current evidence suggests that psychosocial treatments including CBT, MET and CM can increase duration of abstinence from cannabis, reduce frequency of cannabis use, and reduce symptoms of CUD, and their combination may yield most effective results over the long-term. Trials of psychosocial interventions benefit from large sample sizes and multi-site designs, which increase power and generalisability. Of note, clinical trials of psychosocial interventions typically employ waiting list or low-intensity treatments as a control intervention. This could artificially inflate the effect sizes observed in such trials (Furukawa et al., Reference Furukawa, Noma, Caldwell, Honyashiki, Shinohara, Imai and Churchill2014) due to a lack of expectancy from a matched placebo, alongside negative effects of psychosocial control conditions (‘nocebo’ effects), and this should be considered when interpreting findings across different trial designs.

Psychosocial treatment interventions are generally associated with positive during-treatment effects, although these attenuate at follow-up and long-term clinical efficacy needs to be assessed with longer follow-up periods. Most interventions encourage complete abstinence from cannabis use, but are flexible towards individual goals. Sustained abstinence does not occur for the majority of patients. Further evidence is required to compare the efficacy of emerging digital interventions to in-person treatment, and to address the high dropout level observed in online interventions. Research is required to assess whether digital interventions could tackle some of the key barriers to treatment seeking in CUD including stigma and desire for more informal treatment options.

Several trials have investigated substitution treatments (medications containing THC) to treat CUD or aid in detoxification from cannabis. Generally, these trials observe high rates of reduction of cannabis in both treatment and placebo groups, likely due to a beneficial effect of the paired psychotherapies typically employed in experimental and control conditions in these trials. This should be considered when comparing the efficacy of pharmacological treatments with psychosocial treatments, as pharmacological treatments are tested as adjunctive therapies which may limit their potential to provide additional benefits to an effective psychosocial intervention. Additionally, based on the current evidence it is not clear whether psychosocial treatments are necessary in order to promote retention in CUD trials or to facilitate the efficacy of pharmacotherapies. Future trials should aim to investigate the additive or synergistic effects of psychosocial and pharmacological treatments in order to maximise efficacy and cost-effectiveness. Moreover, pharmacological trials are often based on small sample sizes with shorter follow-up periods, a reflection of their currently early phase of assessment.

Despite this, treatments are associated with increased retention as well as reduction in withdrawal symptoms, although a lack of longer-term follow-ups creates difficulty in assessing whether the beneficial impact on reducing withdrawal symptoms translates to meaningful clinical outcome in the long-term. Other pharmacological treatment strategies targeting the endocannabinoid system including CBD and FAAH inhibition show promise, but require replication in larger RCTs with longer follow-up durations.

An important consideration when evaluating findings across trials is that treatment outcome is defined in many different ways. Typically, likelihood or duration of abstinence is included as a primary indicator of treatment success. However, reductions in frequency and quantity of use also mark a positive treatment response, especially when biological measures such as urinalysis are employed to quantify use (Loflin et al., Reference Loflin, Kiluk, Huestis, Aklin, Budney, Carroll and Strain2020). For shorter-term interventions, reduction in cannabis craving or withdrawal may represent positive treatment response in the absence of reduction in cannabis use.

Furthermore, the majority of trials discussed in this review were conducted in samples of >70% male participants. Consequently, the impact of sex on treatment outcomes in CUD is unclear. This is important as women experience more rapid escalation of problems from first use to CUD than men, even when matched for age at first or heavy use (Crocker & Tibbo, Reference Crocker and Tibbo2018; Khan et al., Reference Khan, Secades-Villa, Okuda, Wang, Pérez-Fuentes, Kerridge and Blanco2013). Women also experience more withdrawal symptoms and greater withdrawal severity than men (Herrmann, Weerts, & Vandrey, Reference Herrmann, Weerts and Vandrey2015). Increasing female participants in RCTs for CUD treatment, as well as investigating sex as an a priori moderator of treatment efficacy and safety is needed to establish sex-specific treatment recommendations for clinical practice. Additionally, mental health comorbidities are frequently used as exclusion criteria, which means these samples are likely not representative of the wider population of people with CUD who might respond differently to treatment. Similarly, most trials exclude participants with another substance use disorder (SUD), other than nicotine and caffeine. Where such comorbidities are not an exclusion criterion, they are often not assessed throughout the treatment period and subsequently their impact on treatment outcome is not explored. SUDs commonly overlap with CUD, and also with other mental health disorders (Hasin et al., Reference Hasin, Kerridge, Saha, Huang, Pickering, Smith and Grant2016). Comorbid SUDs can also impact on treatment need and efficacy. For example co-occurring cannabis and tobacco use is associated with increased likelihood of developing CUD, as well as poorer cessation treatment outcomes including relapse to cannabis use (McClure, Rabin, Lee, & Hindocha, Reference McClure, Rabin, Lee and Hindocha2020). Ascertaining the impact of comorbidities on efficacy of treatment for CUD is vital to be able to personalise treatment options depending on the patient's mental health and substance use profile.

Taken together, our recommendations for future interventions for CUD are to ensure that studies are sufficiently powered, in particular by considering recruiting sufficiently large sample sizes to deal with dropout observed in interventions for CUD. Furthermore, researchers should consider whether findings replicate in populations with CUD and mental health comorbidities. Trials should ensure that follow-ups have been planned with sufficient duration to assess whether treatment effects persist following treatment completion. Finally, primary endpoints assessing sustained reduction in cannabis use should be employed alongside, or instead of, measuring sustained abstinence.

Another consideration for future research is the large proportion of individuals not seeking out or accessing treatment who may benefit from it. Among non-treatment seeking users with cannabis dependence, a lack of motivation (not believing anyone could help the problem, wanting to handle the problem alone) has been found to be a major contributor to not seeking treatment (Khan et al., Reference Khan, Secades-Villa, Okuda, Wang, Pérez-Fuentes, Kerridge and Blanco2013). Stigma also appears as a common barrier to treatment, with individuals reporting feeling embarrassed about seeking treatment. Desire to be self-reliant as well as preference for informal treatment options has also been identified in non-treatment seeking users with cannabis dependence (van der Pol et al., Reference van der Pol, Liebregts, de Graaf, Korf, van den Brink and van Laar2013) which may indicate advantages of digital interventions compared to more intensive treatment programmes. Furthermore, improving the information available about treatment services as well as simplifying treatment admission processes have been identified as perceived facilitators of treatment (Gates, Copeland, Swift, & Martin, Reference Gates, Copeland, Swift and Martin2012). Finally, access and affordability of drug treatment options could create a significant barrier to treatment engagement, particularly in countries such as the USA. Therefore, increasing access, acceptability and perhaps variety of treatments is an important goal for alleviating the adverse effects of untreated CUDs. These factors may also relate to individuals' willingness to take part in clinical trials of interventions for CUD, and may partially explain high rates of dropout suffered in such trials (e.g. Mason et al., Reference Mason, Crean, Goodell, Light, Quello, Shadan and Rao2012). Future research should work directly with individuals seeking treatment for CUD, to expand our understanding of the acceptability of current treatment options as well as exploring which factors facilitate treatment seeking.

Finally, this review highlights the particular challenges of treating CUD in people with mental health comorbidities. For example, CM appears effective in those with CUD, however trials have not replicated this effect in those with comorbid psychosis. Most pharmacological interventions have not been explored in people with mental health comorbidities. The lack of efficacious treatments in this population highlights a major unmet clinical need at present. Antipsychotic medication could play an important role in the management of comorbid CUD and psychosis, with some medications such as clozapine and olanzapine associated with a reduction in cannabis craving. Psychosocial treatments targeting dual diagnosis appear beneficial for management of CUD with anxiety and depression. Although mental health comorbidities are common in people with CUD, evidence on the efficacy of treatments in this population is extremely limited and should be addressed as a research priority.

Financial support

RL is funded by an MRC DTP studentship. DCD receives research funding administered through Yale University from the National Institute of Drug Abuse, National Institute of Mental Health, National Center for Advancement of Translational Sciences, Brain and Behavior Foundation, Takeda, Roche, the Heffter Research Institute and the Wallace Foundation. EH reports grants from the Federal Ministry of Health, Federal Ministry of Education and Research, European Monitoring Centre of Drugs and Drug Addiction, during the conduct of the study. TPF was funded by a Senior Academic Fellowship from the Society for the Study of Addiction. LAH is funded by the Wellcome Trust (209158/Z/17/Z). The funders had no role in the development or writing of this manuscript or in the decision to submit it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.