Introduction

Exposure to stressful experiences is an important risk factor for major depressive disorder (MDD) (Kendler et al., Reference Kendler, Karkowski and Prescott1999) – however, not all individuals exposed to stressful experiences develop MDD. This observation is of high relevance for the US Army, whose soldiers routinely encounter stressful events over the course of combat deployment (Adler et al., Reference Adler, McGurk, Stetz and Bliese2004) and show a correspondingly high burden of MDD following deployment (Wells et al., Reference Wells, LeardMann, Fortuna, Smith, Smith, Ryan, Boyko and Blazer2010; Shen et al., Reference Shen, Arkes and Williams2012; Bonde et al., Reference Bonde, Utzon-Frank, Bertelsen, Borritz, Eller, Nordentoft, Olesen, Rod and Rugulies2016). Preventing MDD and its associated disability and comorbidities can improve individual/family wellbeing and troop readiness (Kline et al., Reference Kline, Falca-Dodson, Sussner, Ciccone, Chandler, Callahan and Losonczy2010), and requires attention to risk and protective factors that influence depression.

The diathesis-stress model of depression (Hammen, Reference Hammen2005) posits that some individuals have latent or pre-existing vulnerabilities, or diatheses, that are activated in the presence of stress to produce MDD. One such diathesis is genetic susceptibility, which has been found to substantially increase the risk for MDD episodes in the presence of stressful life events (Kendler et al., Reference Kendler, Kessler, Walters, MacLean, Neale, Heath and Eaves1995). Genetic susceptibility for a complex trait like MDD is thought to be polygenic – influenced by many common variants across the genome, each with relatively small effect sizes (Wray et al., Reference Wray, Lee, Mehta, Vinkhuyzen, Dudbridge and Middeldorp2014). This influence can be indexed by polygenic risk scores (PRS) that combine effects across common variants using results from a discovery genome-wide association study (GWAS). For MDD, a well-powered GWAS with 461 134 individuals (Wray and Sullivan, Reference Wray, Ripke, Mattheisen, Trzaskowski, Byrne, Abdellaoui, Adams, Agerbo, Air, Andlauer, Bacanu, Bækvad-Hansen, Beekman, Bigdeli, Binder, Blackwood, Bryois, Buttenschøn, Bybjerg-Grauholm, Cai, Castelao, Christensen, Clarke, Coleman, Colodro-Conde, Couvy-Duchesne, Craddock, Crawford, Crowley, Dashti, Davies, Deary, Degenhardt, Derks, Direk, Dolan, Dunn, Eley, Eriksson, Escott-Price, Kiadeh, Finucane, Forstner, Frank, Gaspar, Gill, Giusti-Rodríguez, Goes, Gordon, Grove, Hall, Hannon, Hansen, Hansen, Herms, Hickie, Hoffmann, Homuth, Horn, Hottenga, Hougaard, Hu, Hyde, Ising, Jansen, Jin, Jorgenson, Knowles, Kohane, Kraft, Kretzschmar, Krogh, Kutalik, Lane, Li Yihan Li Yun Lind, Liu, Lu, MacIntyre, MacKinnon, Maier, Maier, Marchini, Mbarek, McGrath, McGuffin, Medland, Mehta, Middeldorp, Mihailov, Milaneschi, Milani, Mill, Mondimore, Montgomery, Mostafavi, Mullins, Nauck, Ng, Nivard, Nyholt, O'Reilly, Oskarsson, Owen, Painter, Pedersen, Pedersen, Peterson, Pettersson, Peyrot, Pistis, Posthuma, Purcell, Quiroz, Qvist, Rice, Riley, Rivera, Saeed Mirza, Saxena, Schoevers, Schulte, Shen, Shi, Shyn, Sigurdsson, Sinnamon, Smit, Smith, Stefansson, Steinberg, Stockmeier, Streit, Strohmaier, Tansey, Teismann, Teumer, Thompson, Thomson, Thorgeirsson, Tian, Traylor, Treutlein, Trubetskoy, Uitterlinden, Umbricht, Van der Auwera, van Hemert, Viktorin, Visscher, Wang, Webb, Weinsheimer, Wellmann, Willemsen, Witt, Wu, Xi, Yang, Zhang, Arolt, Baune, Berger, Boomsma, Cichon, Dannlowski, de Geus, DePaulo, Domenici, Domschke, Esko, Grabe, Hamilton, Hayward, Heath, Hinds, Kendler, Kloiber, Lewis, Li, Lucae, Madden, Magnusson, Martin, McIntosh, Metspalu, Mors, Mortensen, Müller-Myhsok, Nordentoft, Nöthen, O'Donovan, Paciga, Pedersen, Penninx, Perlis, Porteous, Potash, Preisig, Rietschel, Schaefer, Schulze, Smoller, Stefansson, Tiemeier, Uher, Völzke, Weissman, Werge, Winslow, Lewis, Levinson, Breen, Børglum and Sullivan2017) has become available, and its derived PRS was recently validated in a diathesis-stress model for MDD in the context of life stressors (Colodro-Conde et al., Reference Colodro-Conde, Couvy-Duchesne, Zhu, Coventry, Byrne, Gordon, Wright, Montgomery, Madden, Ripke, Eaves, Heath, Wray, Medland and Martin2017). However, to date, this PRS has not been prospectively validated in terms of new MDD onset following stress exposure.

While genetic susceptibility is a risk factor for depression, non-genetic protective factors may offset this risk, illuminating opportunities for prevention. Protective factors can be specific to the individual (intrinsic) or related to the individual's environment (extrinsic) (Werner and Zigler, Reference Werner, Zigler, Shonkoff and Meisels2000). One intrinsic factor that has been studied in Army populations is trait resilience, defined as perceived hardiness to stress and ability to cope adaptively with stressors (Connor and Davidson, Reference Connor and Davidson2003). Unit cohesion – which includes emotional safety, bonding, and support between soldiers and with unit leaders – is an extrinsic factor that has also received substantial attention. Although these factors are well characterized for their protective effects on post-deployment mental health (Dolan and Adler, Reference Dolan and Adler2006; Pietrzak et al., Reference Pietrzak, Johnson, Goldstein, Malley and Southwick2009; Wooten, Reference Wooten2012; Zang et al., Reference Zang, Gallagher, McLean, Tannahill, Yarvis and Foa2017), the extent to which they attenuate risk for MDD in the presence of genetic susceptibility has not been examined.

The Army Study of Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS) has followed a large prospective sample of active duty soldiers with genomic data across one combat deployment cycle (Ursano et al., Reference Ursano, Colpe, Heeringa, Kessler, Schoenbaum and Stein2014). This provides a unique opportunity to test the effects of genetic susceptibility and candidate protective factors assessed shortly before deployment, in relation to the development of MDD following deployment. Specifically, we examine whether two putative protective factors – trait resilience (intrinsic) and unit cohesion (extrinsic) – can reduce the risk for incident post-deployment MDD even among soldiers at high polygenic risk for MDD.

Methods

Participants and procedures

The Pre/Post Deployment Study (PPDS) in Army STARRS is a multi-wave panel survey of US Army soldiers from three brigade combat teams that were deployed to Afghanistan in 2012. Soldiers from these brigade combat teams were eligible for this study if they provided written informed consent for participation. Soldiers completed baseline assessments within approximately 6 weeks before deployment, and follow-up assessments at 3 and 9 months post-deployment. For this analysis, the sample was restricted to those with eligible survey responses and samples for genotyping. Procedures for Army STARRS and PPDS have been reported in detail elsewhere (Ursano et al., Reference Ursano, Colpe, Heeringa, Kessler, Schoenbaum and Stein2014; Stein et al., Reference Stein, Kessler, Heeringa, Jain, Campbell-Sills, Colpe, Fullerton, Nock, Sampson, Schoenbaum, Sun, Thomas and Ursano2015), and were approved by the institutional review boards at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Harvard University, University of Michigan, and University of California, San Diego.

Measures

Major depressive disorder

MDD was ascertained at each assessment using items from the major depressive episode (MDE) scale of the WHO Composite International Diagnostic Interview-Screening Scales (CIDI-SC) (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Santiago, Colpe, Dempsey, First, Heeringa, Stein, Fullerton, Gruber, Naifeh, Nock, Sampson, Schoenbaum, Zaslavsky and Ursano2013). Scale items assessed the frequency of MDD symptoms (e.g. depressed mood, loss of interest) over the past 30 days, and were summed to yield overall symptom scores. Symptom scores were then dichotomized using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis to determine clinical thresholds for past 30-day MDEs, as validated elsewhere (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Santiago, Colpe, Dempsey, First, Heeringa, Stein, Fullerton, Gruber, Naifeh, Nock, Sampson, Schoenbaum, Zaslavsky and Ursano2013). Incident MDD was defined as no MDE at baseline, followed by a MDE at any point through 9 months, while the absence of incident MDD was defined as no MDE across both 3 and 9 months (0 = no incident depression, 1 = incident depression). Soldiers who met criteria for an existing MDE at pre-deployment were excluded since MDD incidence could not be established. We included all remaining participants who had complete follow-up MDE data or otherwise met criteria for at least one MDE.

Trait resilience

Trait resilience was self-reported by soldiers at baseline using a five-item scale derived from a larger pool of 17 items that were pilot-tested in earlier Army STARRS surveys and culled using exploratory factor analysis and item response theory analysis for administration in the PPDS. Information on the development and validation of this scale has been published elsewhere (Campbell-Sills et al., Reference Campbell-Sills, Kessler, Ursano, Sun, Taylor, Heeringa, Nock, Sampson, Jain and Stein2018). Participants reported on their abilities to ‘keep calm and think of the right thing to do in a crisis,’ ‘manage stress,’ or to ‘try new approaches if old ones don't work’ (all items described in online Supplementary Materials S1A). Items were rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from ‘poor’ to ‘excellent,’ and summed to yield continuous scores ranging from 0 and 20. Internal consistency was good (α = 0.89). Scores were standardized to a mean of 0 and variance of 1 for analysis.

Unit cohesion

Unit cohesion was assessed at baseline using a seven-item scale developed for this study and adapted from the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (WRAIR) Military Cohesion Scales (Vaitkus, Reference Vaitkus1994). Soldiers reported on perceived support and cohesion within their unit, including items such as ‘I can rely on members of my unit for help if I need it,’ ‘I can open up and talk to my first line leaders if I need help,’ and ‘My leaders take a personal interest in the well-being of all soldiers in my unit’ (all items described in online Supplementary Materials S1B). Items were rated on five-point Likert scale ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree,’ and were summed to yield continuous scores ranging between 0 and 27. Internal consistency was high (α = 0.89); a factor analysis confirmed that one single factor was sufficient to represent shared variability among these seven-scale items. Scores were standardized to a mean of 0 and variance of 1 for analysis.

Combat stress exposure

Within 1 month of return from deployment, soldiers also completed a 15-item measure of combat stress exposure – including engaging in combat patrol or other dangerous duties, and firing at and/or receiving enemy fire. These items (described in online Supplementary Materials S2) were summed to reflect the overall burden of combat stress exposure, as in previous research (Stein et al., Reference Stein, Kessler, Heeringa, Jain, Campbell-Sills, Colpe, Fullerton, Nock, Sampson, Schoenbaum, Sun, Thomas and Ursano2015).

DNA processing

Detailed information about genotyping, imputation, quality control (QC), and population assignment in Army STARRs is available elsewhere (Stein et al., Reference Stein, Chen, Ursano, Cai, Gelernter, Heeringa, Jain, Jensen, Maihofer, Mitchell, Nievergelt, Nock, Neale, Polimanti, Ripke, Sun, Thomas, Wang, Ware, Borja, Kessler and Smoller2016). Briefly, DNA samples for each participant were genotyped using Illumina OmniExpress and Exome array with additional custom content. Initial QC procedures were conducted to retain only (1) samples with genotype missingness <0.02, no extreme autosomal heterozygosity, and no relatedness (if related pairs of individuals were identified, only one was kept); and (2) single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) with genotype missingness <0.05 (before sample QC) and <0.02 (after sample QC), minor allele frequency (MAF) >0.05, and no violation of the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (p > 1 × 10−6).

Prior to imputation, SNPs were also removed if they were not present or had non-matching alleles in the 1000 Genomes Project reference panel (August 2012 phase 1 integrated release) (Auton et al., Reference Auton, Abecasis, Altshuler, Durbin, Abecasis, Bentley, Chakravarti, Clark, Donnelly, Eichler, Flicek, Gabriel, Gibbs, Green, Hurles, Knoppers, Korbel, Lander, Lee, Lehrach, Mardis, Marth, McVean, Nickerson, Schmidt, Sherry, Wang, Wilson, Gibbs, Boerwinkle, Doddapaneni, Han, Korchina, Kovar, Lee, Muzny, Reid, Zhu, Wang, Chang, Feng, Fang, Guo, Jian, Jiang, Jin, Lan, Li G, Li, Li Yingrui Liu, Liu Xiao Lu, Ma, Tang, Wang, Wang, Wu, Wu, Xu, Yin, Zhang, Zhang, Zhao, Zhao, Zheng, Lander, Altshuler, Gabriel, Gupta, Gharani, Toji, Gerry, Resch, Flicek, Barker, Clarke, Gil, Hunt, Kelman, Kulesha, Leinonen, McLaren, Radhakrishnan, Roa, Smirnov, Smith, Streeter, Thormann, Toneva, Vaughan, Zheng-Bradley, Bentley, Grocock, Humphray, James, Kingsbury, Lehrach, Sudbrak, Albrecht, Amstislavskiy, Borodina, Lienhard, Mertes, Sultan, Timmermann, Yaspo, Mardis, Wilson, Fulton, Fulton, Sherry, Ananiev, Belaia, Beloslyudtsev, Bouk, Chen, Church, Cohen, Cook, Garner, Hefferon, Kimelman, Liu, Lopez, Meric, O'Sullivan, Ostapchuk, Phan, Ponomarov, Schneider, Shekhtman, Sirotkin, Slotta, Zhang, McVean, Durbin, Balasubramaniam, Burton, Danecek, Keane, Kolb-Kokocinski, McCarthy, Stalker, Quail, Schmidt, Davies, Gollub, Webster, Wong, Zhan, Auton, Campbell, Kong, Marcketta, Gibbs, Yu, Antunes, Bainbridge, Muzny, Sabo, Huang, Wang, Coin, Fang, Guo, Jin, Li, Li, Li Yingrui Li, Lin, Liu, Luo, Shao, Xie, Ye, Yu, Zhang, Zheng, Zhu, Alkan, Dal, Kahveci, Marth, Garrison, Kural, Lee, Fung Leong, Stromberg, Ward, Wu, Zhang, Daly, DePristo, Handsaker, Altshuler, Banks, Bhatia, del Angel, Gabriel, Genovese, Gupta, Li, Kashin, Lander, McCarroll, Nemesh, Poplin, Yoon, Lihm, Makarov, Clark, Gottipati, Keinan, Rodriguez-Flores, Korbel, Rausch, Fritz, Stütz, Flicek, Beal, Clarke, Datta, Herrero, McLaren, Ritchie, Smith, Zerbino, Zheng-Bradley, Sabeti, Shlyakhter, Schaffner, Vitti, Cooper, Ball, Stenson, Bentley, Barnes, Bauer, Keira Cheetham, Cox, Eberle, Humphray, Kahn, Murray, Peden, Shaw, Kenny, Batzer, Konkel, Walker, MacArthur, Lek, Sudbrak, Amstislavskiy, Herwig, Mardis, Ding, Koboldt, Larson, Ye Kai Gravel, Swaroop, Chew, Lappalainen, Erlich, Gymrek, Frederick Willems, Simpson, Shriver, Rosenfeld, Bustamante, Montgomery, De La Vega, Byrnes, Carroll, DeGorter, Lacroute, Maples, Martin, Moreno-Estrada, Shringarpure, Zakharia, Halperin, Baran, Lee, Cerveira, Hwang, Malhotra, Plewczynski, Radew, Romanovitch, Zhang, Hyland, Craig, Christoforides, Homer, Izatt, Kurdoglu, Sinari, Squire, Sherry, Xiao, Sebat, Antaki, Gujral, Noor, Ye Kenny Burchard, Hernandez, Gignoux, Haussler, Katzman, James Kent, Howie, Ruiz-Linares, Dermitzakis, Devine, Abecasis, Min Kang, Kidd, Blackwell, Caron, Chen, Emery, Fritsche, Fuchsberger, Jun, Li, Lyons, Scheller, Sidore, Song, Sliwerska, Taliun, Tan, Welch, Kate Wing, Zhan, Awadalla, Hodgkinson, Li Yun Shi, Quitadamo, Lunter, McVean, Marchini, Myers, Churchhouse, Delaneau, Gupta-Hinch, Kretzschmar, Iqbal, Mathieson, Menelaou, Rimmer, Xifara, Oleksyk, Fu Yunxin Liu Xiaoming Xiong, Jorde, Witherspoon, Xing, Eichler, Browning, Browning, Hormozdiari, Sudmant, Khurana, Durbin, Hurles, Tyler-Smith, Albers, Ayub, Balasubramaniam, Chen, Colonna, Danecek, Jostins, Keane, McCarthy, Walter, Xue, Gerstein, Abyzov, Balasubramanian, Chen, Clarke, Fu Yao Harmanci, Jin, Lee, Liu, Jasmine Mu, Zhang, Zhang Yan Li Yingrui Luo, Zhu, Alkan, Dal, Kahveci, Marth, Garrison, Kural, Lee, Ward, Wu, Zhang, McCarroll, Handsaker, Altshuler, Banks, del Angel, Genovese, Hartl, Li, Kashin, Nemesh, Shakir, Yoon, Lihm, Makarov, Degenhardt, Korbel, Fritz, Meiers, Raeder, Rausch, Stütz, Flicek, Paolo Casale, Clarke, Smith, Stegle, Zheng-Bradley, Bentley, Barnes, Keira Cheetham, Eberle, Humphray, Kahn, Murray, Shaw, Lameijer, Batzer, Konkel, Walker, Ding, Hall, Ye Kai Lacroute, Lee, Cerveira, Malhotra, Hwang, Plewczynski, Radew, Romanovitch, Zhang, Craig, Homer, Church, Xiao, Sebat, Antaki, Bafna, Michaelson, Ye Kenny Devine, Gardner, Abecasis, Kidd, Mills, Dayama, Emery, Jun, Shi, Quitadamo, Lunter, McVean, Chen, Fan, Chong, Chen, Witherspoon, Xing, Eichler, Chaisson, Hormozdiari, Huddleston, Malig, Nelson, Sudmant, Parrish, Khurana, Hurles, Blackburne, Lindsay, Ning, Walter, Zhang Yujun Gerstein, Abyzov, Chen, Clarke, Lam, Jasmine Mu, Sisu, Zhang, Zhang Yan Gibbs, Yu, Bainbridge, Challis, Evani, Kovar, Lu, Muzny, Nagaswamy, Reid, Sabo, Yu, Guo, Li, Li Yingrui Wu, Marth, Garrison, Fung Leong, Ward, del Angel, DePristo, Gabriel, Gupta, Hartl, Poplin, Clark, Rodriguez-Flores, Flicek, Clarke, Smith, Zheng-Bradley, MacArthur, Mardis, Fulton, Koboldt, Gravel, Bustamante, Craig, Christoforides, Homer, Izatt, Sherry, Xiao, Dermitzakis, Abecasis, Min Kang, McVean, Gerstein, Balasubramanian, Habegger, Yu, Flicek, Clarke, Cunningham, Dunham, Zerbino, Zheng-Bradley, Lage, Berg Jespersen, Horn, Montgomery, DeGorter, Khurana, Tyler-Smith, Chen, Colonna, Xue, Gerstein, Balasubramanian, Fu Yao Kim, Auton, Marcketta, Desalle, Narechania, Wilson Sayres, Garrison, Handsaker, Kashin, McCarroll, Rodriguez-Flores, Flicek, Clarke, Zheng-Bradley, Erlich, Gymrek, Frederick Willems, Bustamante, Mendez, David Poznik, Underhill, Lee, Cerveira, Malhotra, Romanovitch, Zhang, Abecasis, Coin, Shao, Mittelman, Tyler-Smith, Ayub, Banerjee, Cerezo, Chen, Fitzgerald, Louzada, Massaia, McCarthy, Ritchie, Xue, Yang, Gibbs, Kovar, Kalra, Hale, Muzny, Reid, Wang, Dan, Guo, Li, Li Yingrui Ye, Zheng, Altshuler, Flicek, Clarke, Zheng-Bradley, Bentley, Cox, Humphray, Kahn, Sudbrak, Albrecht, Lienhard, Larson, Craig, Izatt, Kurdoglu, Sherry, Xiao, Haussler, Abecasis, McVean, Durbin, Balasubramaniam, Keane, McCarthy, Stalker, Chakravarti, Knoppers, Abecasis, Barnes, Beiswanger, Burchard, Bustamante, Cai, Cao, Durbin, Gerry, Gharani, Gibbs, Gignoux, Gravel, Henn, Jones, Jorde, Kaye, Keinan, Kent, Kerasidou, Li Yingrui Mathias, McVean, Moreno-Estrada, Ossorio, Parker, Resch, Rotimi, Royal, Sandoval, Su, Sudbrak, Tian, Tishkoff, Toji, Tyler-Smith, Via, Wang, Yang, Yang, Zhu, Bodmer, Bedoya, Ruiz-Linares, Cai, Gao, Chu, Peltonen, Garcia-Montero, Orfao, Dutil, Martinez-Cruzado, Oleksyk, Barnes, Mathias, Hennis, Watson, McKenzie, Qadri, LaRocque, Sabeti, Zhu, Deng, Sabeti, Asogun, Folarin, Happi, Omoniwa, Stremlau, Tariyal, Jallow, Sisay Joof, Corrah, Rockett, Kwiatkowski, Kooner, Tịnh Hiê`n, Dunstan, Thuy Hang, Fonnie, Garry, Kanneh, Moses, Sabeti, Schieffelin, Grant, Gallo, Poletti, Saleheen, Rasheed, Brooks, Felsenfeld, McEwen, Vaydylevich, Green, Duncanson, Dunn, Schloss, Wang, Yang, Auton, Brooks, Durbin, Garrison, Min Kang, Korbel, Marchini, McCarthy, McVean and Abecasis2015) or had ambiguous alleles with MAF>0.10. Following a two-step pre-phasing/imputation process (Howie et al., Reference Howie, Fuchsberger, Stephens, Marchini and Abecasis2012), imputed SNPs were converted to ‘best guess’ genotyped SNPs based on their imputation probability. Where no possible genotype met the threshold of 80% probability, information for that SNP was set as missing. SNPs were filtered again to retain missingness <0.02 and imputation quality (INFO) score >0.80, and duplicate SNPs were identified for exclusion in subsequent analyses.

Ancestry was inferred through principal component (PC) analyses as reported previously (Stein et al., Reference Stein, Chen, Ursano, Cai, Gelernter, Heeringa, Jain, Jensen, Maihofer, Mitchell, Nievergelt, Nock, Neale, Polimanti, Ripke, Sun, Thomas, Wang, Ware, Borja, Kessler and Smoller2016). Given that PRS would be constructed using effect sizes obtained in samples of European ancestry (EA) (Wray and Sullivan, Reference Wray, Ripke, Mattheisen, Trzaskowski, Byrne, Abdellaoui, Adams, Agerbo, Air, Andlauer, Bacanu, Bækvad-Hansen, Beekman, Bigdeli, Binder, Blackwood, Bryois, Buttenschøn, Bybjerg-Grauholm, Cai, Castelao, Christensen, Clarke, Coleman, Colodro-Conde, Couvy-Duchesne, Craddock, Crawford, Crowley, Dashti, Davies, Deary, Degenhardt, Derks, Direk, Dolan, Dunn, Eley, Eriksson, Escott-Price, Kiadeh, Finucane, Forstner, Frank, Gaspar, Gill, Giusti-Rodríguez, Goes, Gordon, Grove, Hall, Hannon, Hansen, Hansen, Herms, Hickie, Hoffmann, Homuth, Horn, Hottenga, Hougaard, Hu, Hyde, Ising, Jansen, Jin, Jorgenson, Knowles, Kohane, Kraft, Kretzschmar, Krogh, Kutalik, Lane, Li Yihan Li Yun Lind, Liu, Lu, MacIntyre, MacKinnon, Maier, Maier, Marchini, Mbarek, McGrath, McGuffin, Medland, Mehta, Middeldorp, Mihailov, Milaneschi, Milani, Mill, Mondimore, Montgomery, Mostafavi, Mullins, Nauck, Ng, Nivard, Nyholt, O'Reilly, Oskarsson, Owen, Painter, Pedersen, Pedersen, Peterson, Pettersson, Peyrot, Pistis, Posthuma, Purcell, Quiroz, Qvist, Rice, Riley, Rivera, Saeed Mirza, Saxena, Schoevers, Schulte, Shen, Shi, Shyn, Sigurdsson, Sinnamon, Smit, Smith, Stefansson, Steinberg, Stockmeier, Streit, Strohmaier, Tansey, Teismann, Teumer, Thompson, Thomson, Thorgeirsson, Tian, Traylor, Treutlein, Trubetskoy, Uitterlinden, Umbricht, Van der Auwera, van Hemert, Viktorin, Visscher, Wang, Webb, Weinsheimer, Wellmann, Willemsen, Witt, Wu, Xi, Yang, Zhang, Arolt, Baune, Berger, Boomsma, Cichon, Dannlowski, de Geus, DePaulo, Domenici, Domschke, Esko, Grabe, Hamilton, Hayward, Heath, Hinds, Kendler, Kloiber, Lewis, Li, Lucae, Madden, Magnusson, Martin, McIntosh, Metspalu, Mors, Mortensen, Müller-Myhsok, Nordentoft, Nöthen, O'Donovan, Paciga, Pedersen, Penninx, Perlis, Porteous, Potash, Preisig, Rietschel, Schaefer, Schulze, Smoller, Stefansson, Tiemeier, Uher, Völzke, Weissman, Werge, Winslow, Lewis, Levinson, Breen, Børglum and Sullivan2017), only PPDS participants assigned to the EA group were retained (N = 4900). By inspecting successive PC plots within the EA group for evidence of population structure, we determined only the first three PCs were likely relevant for inclusion as covariates in subsequent analyses.

Polygenic risk scoring

To construct the PRS, we obtained summary statistics from the latest GWAS of major depression in 461 134 individuals (Wray and Sullivan, Reference Wray, Ripke, Mattheisen, Trzaskowski, Byrne, Abdellaoui, Adams, Agerbo, Air, Andlauer, Bacanu, Bækvad-Hansen, Beekman, Bigdeli, Binder, Blackwood, Bryois, Buttenschøn, Bybjerg-Grauholm, Cai, Castelao, Christensen, Clarke, Coleman, Colodro-Conde, Couvy-Duchesne, Craddock, Crawford, Crowley, Dashti, Davies, Deary, Degenhardt, Derks, Direk, Dolan, Dunn, Eley, Eriksson, Escott-Price, Kiadeh, Finucane, Forstner, Frank, Gaspar, Gill, Giusti-Rodríguez, Goes, Gordon, Grove, Hall, Hannon, Hansen, Hansen, Herms, Hickie, Hoffmann, Homuth, Horn, Hottenga, Hougaard, Hu, Hyde, Ising, Jansen, Jin, Jorgenson, Knowles, Kohane, Kraft, Kretzschmar, Krogh, Kutalik, Lane, Li Yihan Li Yun Lind, Liu, Lu, MacIntyre, MacKinnon, Maier, Maier, Marchini, Mbarek, McGrath, McGuffin, Medland, Mehta, Middeldorp, Mihailov, Milaneschi, Milani, Mill, Mondimore, Montgomery, Mostafavi, Mullins, Nauck, Ng, Nivard, Nyholt, O'Reilly, Oskarsson, Owen, Painter, Pedersen, Pedersen, Peterson, Pettersson, Peyrot, Pistis, Posthuma, Purcell, Quiroz, Qvist, Rice, Riley, Rivera, Saeed Mirza, Saxena, Schoevers, Schulte, Shen, Shi, Shyn, Sigurdsson, Sinnamon, Smit, Smith, Stefansson, Steinberg, Stockmeier, Streit, Strohmaier, Tansey, Teismann, Teumer, Thompson, Thomson, Thorgeirsson, Tian, Traylor, Treutlein, Trubetskoy, Uitterlinden, Umbricht, Van der Auwera, van Hemert, Viktorin, Visscher, Wang, Webb, Weinsheimer, Wellmann, Willemsen, Witt, Wu, Xi, Yang, Zhang, Arolt, Baune, Berger, Boomsma, Cichon, Dannlowski, de Geus, DePaulo, Domenici, Domschke, Esko, Grabe, Hamilton, Hayward, Heath, Hinds, Kendler, Kloiber, Lewis, Li, Lucae, Madden, Magnusson, Martin, McIntosh, Metspalu, Mors, Mortensen, Müller-Myhsok, Nordentoft, Nöthen, O'Donovan, Paciga, Pedersen, Penninx, Perlis, Porteous, Potash, Preisig, Rietschel, Schaefer, Schulze, Smoller, Stefansson, Tiemeier, Uher, Völzke, Weissman, Werge, Winslow, Lewis, Levinson, Breen, Børglum and Sullivan2017). For the main analyses, we used the set of summary statistics without 23andMe data (N = 173 005) that is now publicly available. After removal of ambiguous SNPs, we clumped the GWAS summary statistics using our EA genomic data to limit the inclusion of highly correlated SNPs, using a r 2 threshold of 0.25 and a 250 kb window. These clumped summary statistics were used to compute PRS from our EA genomic data that included SNPs whose effects met the following p-value thresholds (pT) in decreasing order of stringency: 5 × 10−8, <0.0001, <0.001, 0.01, 0.05, 0.10, 0.50, 1.0. PRS were calculated as the total sum of risk alleles at each eligible SNP weighted by their estimated effect size (log odds ratio), divided by total number of SNPs included for scoring (online Supplementary Table S2A).

Statistical analyses

First, we examined the MDD PRS at varying p-value thresholds in relation to incident MDD (online Supplementary Fig. S3A). The PRS at the p-value threshold with largest Nagelkerke's pseudo-R 2 (pT = 0.01) above and beyond a covariates-only model was selected for subsequent analyses (Ripke et al., Reference Ripke, O'Dushlaine, Chambert, Moran, Kähler, Akterin, Bergen, Collins, Crowley, Fromer, Kim, Lee, Magnusson, Sanchez, Stahl, Williams, Wray, Xia, Bettella, Borglum, Bulik-Sullivan, Cormican, Craddock, de Leeuw, Durmishi, Gill, Golimbet, Hamshere, Holmans, Hougaard, Kendler, Lin, Morris, Mors, Mortensen, Neale, O'Neill, Owen, Milovancevic, Posthuma, Powell, Richards, Riley, Ruderfer, Rujescu, Sigurdsson, Silagadze, Smit, Stefansson, Steinberg, Suvisaari, Tosato, Verhage, Walters, Levinson, Gejman, Kendler, Laurent, Mowry, O'Donovan, Owen, Pulver, Riley, Schwab, Wildenauer, Dudbridge, Holmans, Shi, Albus, Alexander, Campion, Cohen, Dikeos, Duan, Eichhammer, Godard, Hansen, Lerer, Liang, Maier, Mallet, Nertney, Nestadt, Norton, O'Neill, Papadimitriou, Ribble, Sanders, Silverman, Walsh, Williams, Wormley, Arranz, Bakker, Bender and Bramon2013). This PRS was distributed across individuals and divided into three groups of polygenic risk (online Supplementary Table S3B): low (quintile 1), intermediate (quintiles 2–4), and high (quintile 5) (Khera et al., Reference Khera, Emdin, Drake, Natarajan, Bick, Cook, Chasman, Baber, Mehran, Rader, Fuster, Boerwinkle, Melander, Orho-Melander, Ridker and Kathiresan2016). Second, we used logistic regressions to examine the main effects of polygenic risk on incident MDD, using the low-risk group as the reference group. Third, we used logistic regressions to examine the main effects of each protective factor on incident MDD. Fourth, we tested the effects of each protective factor (per standardized unit score) on incident MDD across polygenic risk groups, correcting for testing three separate models with a Bonferroni-corrected p-value of 0.017 (0.05/3). At each step, we adjusted for sex, age, and PCs to account for population stratification when polygenic scores were included. For any protective factor that showed protective effects for incident MDD in the context of polygenic risk, we conducted similar within-group analyses to test whether this factor would also show protective effects in the context of environmental risk (i.e. combat stress exposure). All analyses were conducted in R.

Results

Sample characteristics

Our sample consisted of PPDS participants of EA who provided genome-wide data, excluding soldiers with an existing MDE at pre-deployment (N = 310) and including all participants who had complete follow-up MDE data or otherwise met criteria for at least one MDE (resulting N = 3079). The sample was predominantly (96%) male and younger than 30-years-old (mean = 25.9, s.d. = 5.8). At baseline, soldiers tended to report high trait resilience scores (mean = 15.1, s.d. = 4.0, max = 20) and perceived their units as relatively cohesive (mean = 19.7, s.d. = 5.4, max = 27). During deployment, soldiers reported experiencing an average of 4.1 major combat-related stressors (max = 13.0, s.d. = 2.8). Within 9 months of returning from deployment, 13% (N = 390) met criteria for incident MDD.

Are polygenic risk and protective factors associated with incident MDD?

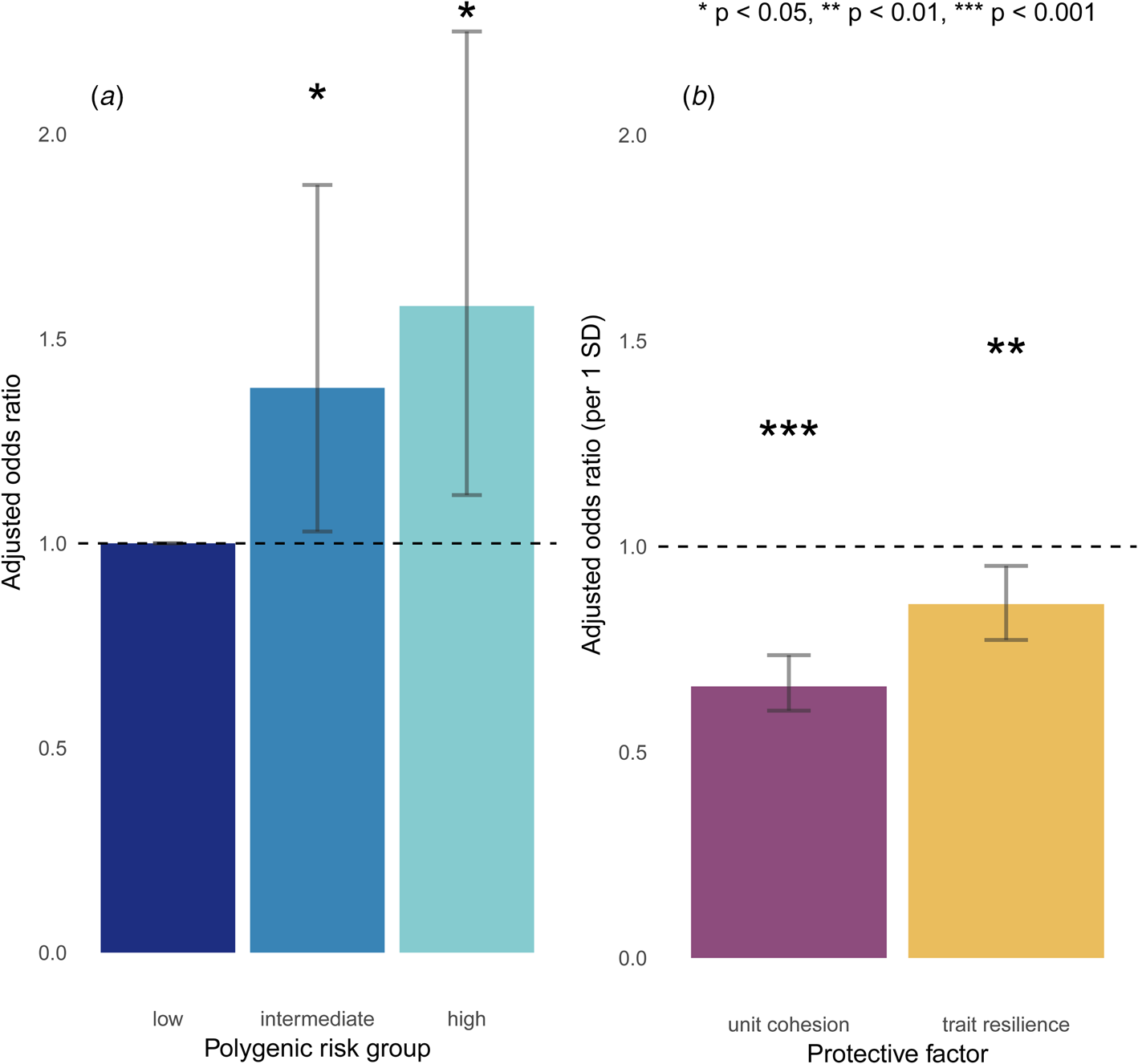

Polygenic risk showed a dose-response relationship with incident MDD. Compared to soldiers at low polygenic risk, odds for incident MDD were highest in soldiers at high polygenic risk [adjusted odds ratio (aOR) = 1.58, 95% profile confidence interval (CI) = 1.12–2.25, p = 0.01] and more modestly increased in those at intermediate polygenic risk (aOR = 1.38, 95% CI = 1.03–1.88, p = 0.04) (Fig. 1a; full model results in online Supplementary Table S3B).

Fig. 1. Main effects of (a) polygenic risk and (b) protective factors on incident MDD.

Soldiers who reported stronger unit cohesion at baseline had reduced odds for incident MDD (aOR = 0.67, 95% CI = 0.60–0.74, p = 3.5 × 10−15), as did those who reported higher trait resilience (aOR = 0.86, 95% CI = 0.77–0.95, p = 3.2 × 10−3 (Fig. 1b). Of note, unit cohesion and trait resilience were not significantly correlated with polygenic risk (r = −0.02, p = 0.30; r = −0.01, p = 0.68, respectively), suggesting that the PRS for MDD was relatively specific to depression v. other traits in this sample.

Across the spectrum of polygenic risk, what are the effects of trait resilience and unit cohesion on incident MDD?

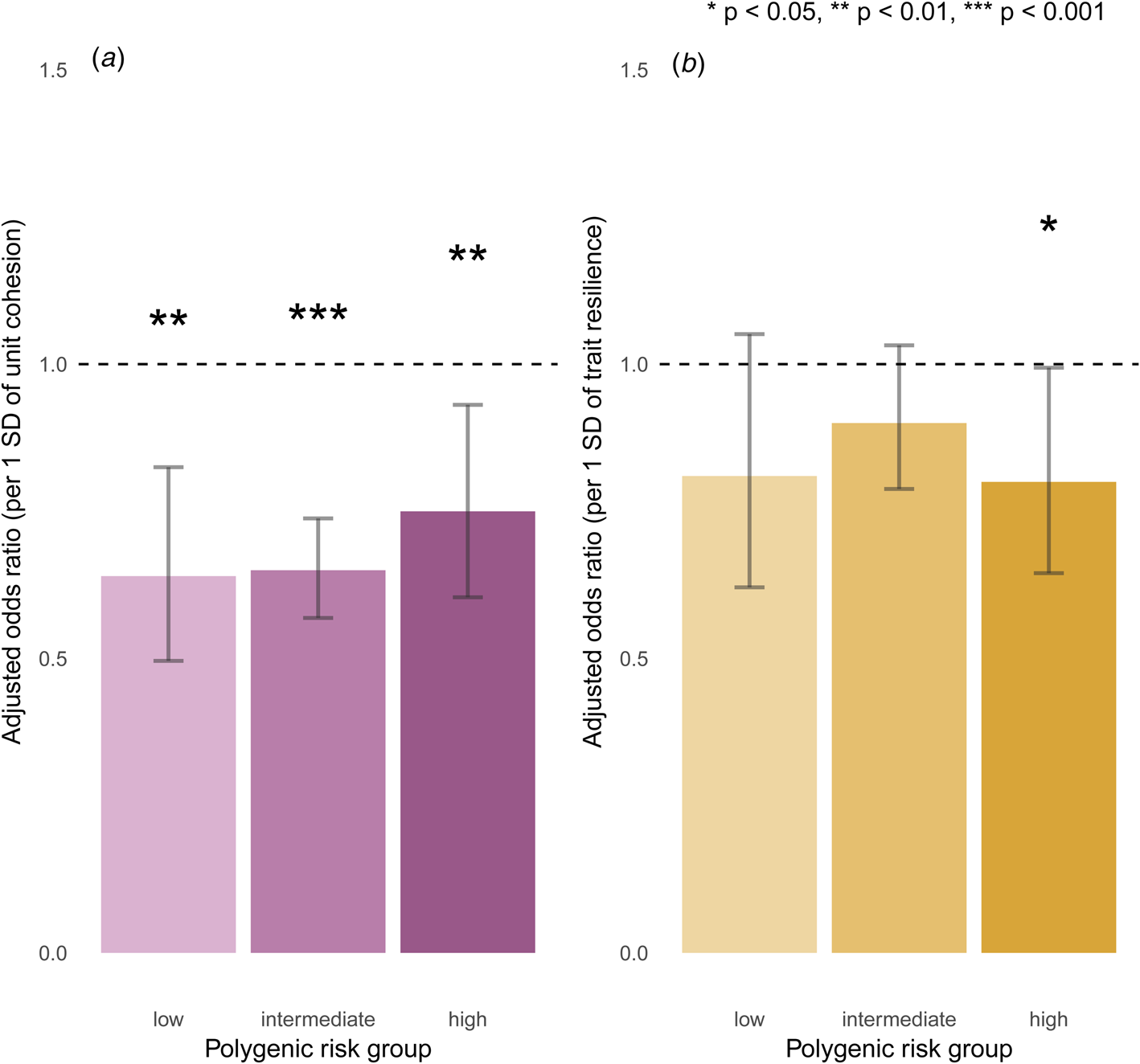

Across all strata of polygenic risk, soldiers who reported stronger unit cohesion had significantly lower odds for incident MDD (low: aOR = 0.64, 95% CI = 0.50–0.83, p = 5.4 × 10−4; intermediate: aOR = 0.65, 95% CI = 0.57–0.74, p = 6.4 × 10−11; high: aOR = 0.75, 95% CI = 0.60–0.93, p = 8.8 × 10−3), after Bonferroni correction. Notably, even among those at highest polygenic risk, unit cohesion was associated with reduced incidence of post-deployment MDD (Fig. 2a). Trait resilience showed similar but only nominally significant effects for incident MDD across strata of polygenic risk (low: aOR = 0.81, 95% CI = 0.62–1.05, p = 0.11; intermediate: aOR = 0.90, 95% CI = 0.79–1.03, p = 0.13; high: aOR = 0.80, 95% CI = 0.65–0.99, p = 0.04), after Bonferroni correction (Fig. 2b). Follow-up regressions confirmed independent and non-interactive effects of polygenic risk – both categorically and continuously defined – as well as unit cohesion, but not trait resilience, on incident MDD (online Supplementary Tables S3C–S3F).

Fig. 2. Effects of (a) unit cohesion and (b) trait resilience on incident MDD, stratified by polygenic risk.

Does unit cohesion also protect against MDD across different levels of environmental risk?

To further explore the protective effect of unit cohesion across different sources of risk, we stratified soldiers by combat stress exposure: low (quintile 1), intermediate (quintiles 2–4), and high (quintile 5). Combat stress exposure was itself a risk factor for incident MDD (aOR = 1.11 per additional exposure, 95% CI = 1.07–1.15, p = 3.1 × 10−8). Unit cohesion remained protective against incident MDD across all levels of combat stress exposure (low: aOR = 0.58, 95% CI = 0.47–0.71, p = 3.7 × 10−7; intermediate: aOR = 0.75, 95% CI = 0.64–0.87, p = 1.7 × 10−4; high: aOR = 0.63, 95% CI = 0.52–0.76, p = 1.7 × 10−6), even for those who reported high levels of combat stress (Fig. 3). Follow-up regression confirmed independent and non-interactive effects of polygenic risk, unit cohesion, and combat stress exposure on incident MDD (online Supplementary Table S3G).

Fig. 3. Effects of unit cohesion on incident MDD across levels of combat stress exposure.

Discussion

Prior research has established that genetic vulnerability and stressful experiences increase the risk for depression – however, two important areas have remained underexplored. First, an emphasis on risk factors has provided little information about the potential for protective factors to promote resilience in the face of genetic or environmental risks. Second, while we know that genetic vulnerability confers risk for depression, implications for actionable or clinically relevant opportunities for prevention are largely unknown. Here, we take advantage of a unique, large-scale, prospectively studied cohort of Army soldiers for whom both genomic data and exposure to a defined class of stressors is available, to answer questions about the nature of risk and protective factors for depression. We find that unit cohesion – an index of social support and morale – is prospectively associated with reduced risk for post-deployment depression, and that this protective effect persists even for soldiers with high genetic or environmental risk.

Our work makes a number of contributions to the literature. First, we demonstrate for the first time that polygenic risk is prospectively associated with new-onset depression following stress exposure. Drawing on large-scale GWAS of major depression (Wray and Sullivan, Reference Wray, Ripke, Mattheisen, Trzaskowski, Byrne, Abdellaoui, Adams, Agerbo, Air, Andlauer, Bacanu, Bækvad-Hansen, Beekman, Bigdeli, Binder, Blackwood, Bryois, Buttenschøn, Bybjerg-Grauholm, Cai, Castelao, Christensen, Clarke, Coleman, Colodro-Conde, Couvy-Duchesne, Craddock, Crawford, Crowley, Dashti, Davies, Deary, Degenhardt, Derks, Direk, Dolan, Dunn, Eley, Eriksson, Escott-Price, Kiadeh, Finucane, Forstner, Frank, Gaspar, Gill, Giusti-Rodríguez, Goes, Gordon, Grove, Hall, Hannon, Hansen, Hansen, Herms, Hickie, Hoffmann, Homuth, Horn, Hottenga, Hougaard, Hu, Hyde, Ising, Jansen, Jin, Jorgenson, Knowles, Kohane, Kraft, Kretzschmar, Krogh, Kutalik, Lane, Li Yihan Li Yun Lind, Liu, Lu, MacIntyre, MacKinnon, Maier, Maier, Marchini, Mbarek, McGrath, McGuffin, Medland, Mehta, Middeldorp, Mihailov, Milaneschi, Milani, Mill, Mondimore, Montgomery, Mostafavi, Mullins, Nauck, Ng, Nivard, Nyholt, O'Reilly, Oskarsson, Owen, Painter, Pedersen, Pedersen, Peterson, Pettersson, Peyrot, Pistis, Posthuma, Purcell, Quiroz, Qvist, Rice, Riley, Rivera, Saeed Mirza, Saxena, Schoevers, Schulte, Shen, Shi, Shyn, Sigurdsson, Sinnamon, Smit, Smith, Stefansson, Steinberg, Stockmeier, Streit, Strohmaier, Tansey, Teismann, Teumer, Thompson, Thomson, Thorgeirsson, Tian, Traylor, Treutlein, Trubetskoy, Uitterlinden, Umbricht, Van der Auwera, van Hemert, Viktorin, Visscher, Wang, Webb, Weinsheimer, Wellmann, Willemsen, Witt, Wu, Xi, Yang, Zhang, Arolt, Baune, Berger, Boomsma, Cichon, Dannlowski, de Geus, DePaulo, Domenici, Domschke, Esko, Grabe, Hamilton, Hayward, Heath, Hinds, Kendler, Kloiber, Lewis, Li, Lucae, Madden, Magnusson, Martin, McIntosh, Metspalu, Mors, Mortensen, Müller-Myhsok, Nordentoft, Nöthen, O'Donovan, Paciga, Pedersen, Penninx, Perlis, Porteous, Potash, Preisig, Rietschel, Schaefer, Schulze, Smoller, Stefansson, Tiemeier, Uher, Völzke, Weissman, Werge, Winslow, Lewis, Levinson, Breen, Børglum and Sullivan2017), we observe a dose–response relationship between polygenic risk and incident MDD following combat deployment, with a 52% increase in relative odds between soldiers in the top and bottom quintiles of polygenic risk. Such differences suggest that PRS meaningfully explained the increased risk for depression in our sample. Although PRS have known limitations (Wray et al., Reference Wray, Yang, Hayes, Price, Goddard and Visscher2013; Bogdan et al., Reference Bogdan, Baranger and Agrawal2018) – notably the fact that they still explain limited variance in psychiatric outcomes, in addition to being constrained to the scope and size of existing GWAS, which limit current predictive utility in clinical settings – they may prove informative in their ability to stratify risk for epidemiological investigation.

Second, we provide novel evidence that strong unit cohesion prior to deployment may offset psychiatric risk despite underlying genetic susceptibility. Protective effects in the presence of high polygenic risk have been shown in cardiology (Khera et al., Reference Khera, Emdin, Drake, Natarajan, Bick, Cook, Chasman, Baber, Mehran, Rader, Fuster, Boerwinkle, Melander, Orho-Melander, Ridker and Kathiresan2016) and we now apply this framework in psychiatry. While previous research has identified unit cohesion as a protective factor for mental health following deployment, most studies have been cross-sectional (Pietrzak et al., Reference Pietrzak, Johnson, Goldstein, Malley and Southwick2009; Armistead-Jehle et al., Reference Armistead-Jehle, Johnston, Wade and Ecklund2011; Du Preez et al., Reference Du Preez, Sundin, Wessely and Fear2012; Goldmann et al., Reference Goldmann, Calabrese, Prescott, Tamburrino, Liberzon, Slembarski, Shirley, Fine, Goto, Wilson, Ganocy, Chan, Serrano, Sizemore and Galea2012; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Seddon, Fear, McAllister, Wessely and Greenberg2012; Kanesarajah et al., Reference Kanesarajah, Waller, Zheng and Dobson2016; Zang et al., Reference Zang, Gallagher, McLean, Tannahill, Yarvis and Foa2017) and ours represents at least a four-fold increase in scale compared to existing prospective studies of unit cohesion and mental health (Polusny et al., Reference Polusny, Erbes, Murdoch, Arbisi, Thuras and Rath2011; Han et al., Reference Han, Castro, Lee, Charney, Marx, Brailey, Proctor and Vasterling2014), in addition to being the first to integrate genetic data.

Third, we corroborate prior evidence that unit cohesion is associated with reduced risk for incident MDD despite high levels of combat stress exposure (Armistead-Jehle et al., Reference Armistead-Jehle, Johnston, Wade and Ecklund2011; Polusny et al., Reference Polusny, Erbes, Murdoch, Arbisi, Thuras and Rath2011; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Seddon, Fear, McAllister, Wessely and Greenberg2012; Han et al., Reference Han, Castro, Lee, Charney, Marx, Brailey, Proctor and Vasterling2014; Kanesarajah et al., Reference Kanesarajah, Waller, Zheng and Dobson2016) and extend this to show that pre-deployment unit cohesion, combat stress exposure, and genetic susceptibility additively, and to some extent orthogonally, influence risk for incident MDD. Together, this suggests that unit cohesion may be widely beneficial for soldiers despite genetic or environmental risk. Unit cohesion has been conceptualized as a multi-faceted construct (Siebold, Reference Siebold1999), including horizontal cohesion (e.g. perceived support from fellow soldiers, sense of bonding and camaraderie between soldiers, trust and reliance on fellow soldiers) and vertical cohesion (e.g. respect and appreciation from unit leaders; clear communication with unit leaders) (Manning, Reference Manning, Franklin D., Linette R., Victoria L. and Joseph M.1994). Our measure tapped into both aspects of unit cohesion, particularly respect and support between soldiers and with their leaders. Given the inevitable stressors encountered during deployment, feeling comfortable seeking help and/or raising concerns may facilitate better coping than self-directed efforts to regulate stress (Berkman, Reference Berkman2000). Moreover, strengthening such dimensions of unit cohesion is putatively actionable (Greden et al., Reference Greden, Valenstein, Spinner, Blow, Gorman, Dalack, Marcus and Kees2010; Williams et al., Reference Williams, Brown, Bray, Anderson Goodell, Rae Olmsted and Adler2016) – for example, by providing leadership skills training, facilitating regular team-based interactions between soldiers during training, and keeping units operationally intact across training and deployment – though interventions remain to be rigorously tested.

Our study has several limitations. First, our analyses focused on two protective factors as exemplars of intrinsic v. extrinsic pre-deployment features, and have not tested a comprehensive set of protective factors that could reduce the risk for MDD. Notably, even with the inclusion of protective factors, polygenic risk, demographic factors, and combat exposure, and our models still explained a relatively small proportion of variance in risk for MDD (online Supplementary Tables S3B–S3G), which highlights the complexity of predicting MDD even with robust variables and a relatively homogeneous population. Second, our construct of unit cohesion was measured at the individual level and may thus capture both extrinsic factors (e.g. quality of relationships, unit culture) as well as intrinsic factors that influence soldiers’ perceptions of unit cohesion (e.g. agreeableness, current distress). Future studies could use unit-level cohesion scores to further circumvent reporting bias, account for potential clustering within units, and better isolate unit cohesion as an exogenous risk factor. However, individual reports may better capture the soldier's own social experience within the unit, which could be most relevant for psychiatric risk. Third, in order to establish incident MDD, we restricted our sample so that no participant met criteria for a 30-day depressive episode shortly before deployment. However, we did not exclude subthreshold symptoms; lifetime MDD in partial or full remission at the baseline assessment; and/or other comorbid psychopathology; and it is possible that such factors would have contributed to predicting post-deployment MDD. Despite combat exposure, rates of MDD in this Army sample were generally comparable to those observed in the population at large. This may be due to the fact that soldiers with greater mental health vulnerabilities may have not been deployed to combat or previously left Army service. We also chose to examine MDD as a form of clinically significant depression requiring targeted attention, rather than depressive symptoms across a continuum. Notably, we found similar results (not shown) when considering average post-deployment depressive symptoms – in that polygenic risk was not only associated with greater symptom severity, but unit cohesion was also linked to significantly decreased symptom severity even among soldiers at high polygenic risk. While this study focused on MDD given availability of a relevant polygenic score, future work could also examine other manifestations of psychopathology following deployment, including substance use and other stress-related disorders, as genome-wide discovery progresses. Fourth, our MDD PRS was based on a reduced GWAS meta-analytic sample for which results are publicly available, which may limit power to capture all polygenic influences on MDD. Finally, our sample was primarily male and was limited to individuals of EA (to maximize the power of the PRS which was based on GWAS of EA subjects). Thus, our results may not generalize beyond Army populations or to female or non-EA individuals.

In conclusion, our findings support a role for both genetic and environmental factors in influencing psychiatric risk in soldiers across combat deployment. In this prospective inquiry, we showed that soldiers who experienced strong unit cohesion shortly before deployment were at reduced risk for incident MDD following deployment, regardless of their genetic susceptibility. This study illustrates the potential of protective factors to offset psychiatric risk following exposure to stressful events. Importantly, potentially actionable factors such as group cohesion and social support may protect against depression even among those most genetically susceptible, and represent promising targets for promoting resilience in at-risk populations.

Author ORCIDs

Karmel W. Choi, 0000-0002-3914-2431; Murray B. Stein, 0000-0001-9564-2871; Jordan W. Smoller 0000-0002-0381-6334

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291719000527

Acknowledgements

Army STARRS was sponsored by the Department of the Army and funded under cooperative agreement number |U01MH087981 (2009–2015) with the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health (NIH/NIMH). Subsequently, STARRS-LS was sponsored and funded by the Department of Defense (USUHS grant number HU0001–15-2-0004). The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Health and Human Services, NIMH, the Department of the Army, or the Department of Defense. Dr Choi was supported in part by a NIMH T32 Training Fellowship (T32MH017119). Dr Smoller is a Tepper Family MGH Research Scholar and supported in part by the Demarest Lloyd, Jr, Foundation and NIH grant K24MH094614. The Major Depressive Disorder Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium was supported in part by NIH grant U01MH109528.

The STARRS Team:

Co-Principal Investigators: Robert J. Ursano, M.D. (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences) and Murray B. Stein, M.D., MPH (University of California San Diego and VA San Diego Healthcare System)

Site Principal Investigators: Steven Heeringa, Ph.D. (University of Michigan), James Wagner, Ph.D. (University of Michigan) and Ronald C. Kessler, Ph.D. (Harvard Medical School)

Army liaison/consultant: Kenneth Cox, M.D., MPH (USAPHC (Provisional))

Other team members: Pablo A. Aliaga, MS (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); COL David M. Benedek, M.D. (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Susan Borja, Ph.D. (NIMH); Tianxi Cai, ScD (Harvard School of Public Health); Laura Campbell-Sills, Ph.D. (University of California San Diego); Carol S. Fullerton, Ph.D. (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Nancy Gebler, MA (University of Michigan); Robert K. Gifford, Ph.D. (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Paul E. Hurwitz, MPH (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Kevin Jensen, Ph.D. (Yale University); Kristen Jepsen, Ph.D. (University of California San Diego); Tzu-Cheg Kao, Ph.D. (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Lisa Lewandowski-Romps, Ph.D. (University of Michigan); Holly Herberman Mash, Ph.D. (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); James E. McCarroll, Ph.D., MPH (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Colter Mitchell, Ph.D. (University of Michigan); James A. Naifeh, Ph.D. (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Tsz Hin Hinz Ng, MPH (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Caroline Nievergelt, Ph.D. (University of California San Diego); Nancy A. Sampson, BA (Harvard Medical School); CDR Patcho Santiago, M.D., MPH (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Ronen Segman, M.D. (Hadassah University Hospital, Israel); Alan M. Zaslavsky, Ph.D. (Harvard Medical School); and Lei Zhang, M.D. (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences).

Conflicts of interest

Dr Stein has in the past 3 years been a consultant for Actelion, Aptinyx, Dart Neuroscience, Healthcare Management Technologies, Janssen, Neurocrine Biosciences, Oxeia Biopharmaceuticals, Pfizer, and Resilience Therapeutics. Dr Stein owns founders shares and stock options in Resilience Therapeutics and has stock options in Oxeia Biopharmaceticals. Dr Smoller is an unpaid member of the Scientific Advisory Board of Psy Therapeutics, Inc and of the Bipolar/Depression Research Community Advisory Panel of 23andMe. In the past 3 years, Dr Kessler has been a consultant for Hoffman-La Roche, Inc., Johnson & Johnson Wellness and Prevention, and Sanofi-Aventis Groupe. Dr Kessler has served on advisory boards for Mensante Corporation, Plus One Health Management, Lake Nona Institute, and US Preventive Medicine. Dr Kessler owns 25% share in DataStat, Inc. The remaining authors report nothing to disclose.