Introduction

Bereavement is one of the most common and severe stressors in one's life (Breslau, Kessler, Chilcoat, Schultz, & Andreski, Reference Breslau, Kessler, Chilcoat, Schultz and Andreski1998). Whereas most bereaved individuals experience acute grief, with presenting signs and symptoms that fade away over a relatively short period of time, as many as 10% of the overall bereaved population experience prolonged grief reactions (Bonanno et al., Reference Bonanno, Wortman, Lehman, Tweed, Haring, Sonnega and Nesse2002; Melhem, Porta, Shamseddeen, Walker Payne, & Brent, Reference Melhem, Porta, Shamseddeen, Walker Payne and Brent2011; Prigerson et al., Reference Prigerson, Horowitz, Jacobs, Parkes, Aslan, Goodkin and Maciejewski2009; Shear et al., Reference Shear, Monk, Houck, Melhem, Frank, Reynolds and Sillowash2007), which is characterized by a heightened intensity of grief symptoms that persists over prolonged periods of time and results in functional impairment. Symptoms of prolonged grief include strong yearning for the deceased person, intense sorrow, recurrent distressing thoughts of the deceased, difficulty accepting the death, and a sense of loneliness and hopelessness; and are associated with functional and social impairment, increased risk for depression, suicidality, and mental and physical health problems (Boelen & Prigerson, Reference Boelen and Prigerson2007; Latham & Prigerson, Reference Latham and Prigerson2004; Melhem et al., Reference Melhem, Day, Shear, Day, Reynolds and Brent2004, Reference Melhem, Porta, Shamseddeen, Walker Payne and Brent2011; Melhem, Moritz, Walker, Shear, & Brent, Reference Melhem, Moritz, Walker, Shear and Brent2007; Ott, Lueger, Kelber, & Prigerson, Reference Ott, Lueger, Kelber and Prigerson2007; Prigerson et al., Reference Prigerson, Bierhals, Kasl, Reynolds, Shear, Day and Jacobs1997, Reference Prigerson, Bridge, Maciejewski, Beery, Rosenheck, Jacobs and Brent1999; Shear et al., Reference Shear, Monk, Houck, Melhem, Frank, Reynolds and Sillowash2007; Simon et al., Reference Simon, Shear, Thompson, Zalta, Perlman, Reynolds and Silowash2007; Szanto et al., Reference Szanto, Shear, Houck, Reynolds, Frank, Caroff and Silowash2006). The prevalence of prolonged grief is particularly elevated among those bereaved by sudden death, especially attributable to disasters or violent deaths (Ghaffari-Nejad, Ahmadi-Mousavi, Gandomkar, & Reihani-Kermani, Reference Ghaffari-Nejad, Ahmadi-Mousavi, Gandomkar and Reihani-Kermani2007; Melhem et al., Reference Melhem, Day, Shear, Day, Reynolds and Brent2004; Mitchell, Kim, Prigerson, & Mortimer-Stephens, Reference Mitchell, Kim, Prigerson and Mortimer-Stephens2004; Neria et al., Reference Neria, Gross, Litz, Insel, Seirmarco, Rosenfeld and Marshall2007). Older age, lower level of education, relationship to the deceased (spouse or child), and anxious/avoidant attachment styles are risk factors for developing prolonged grief (Meert et al., Reference Meert, Donaldson, Newth, Harrison, Berger and Zimmerman2010; Newson, Boelen, Hek, Hofman, & Tiemeier, Reference Newson, Boelen, Hek, Hofman and Tiemeier2011). In addition, a previous history of psychiatric illness, particularly depression and childhood history of separation anxiety, predicts the development of prolonged grief following bereavement (Melhem et al., Reference Melhem, Rosales, Karageorge, Reynolds, Frank and Shear2001).

In the literature, different terminologies have been used to refer to this condition and several criteria have been proposed in adults for complicated grief or CG (Shear, Frank, Houck, & Reynolds, Reference Shear, Frank, Houck and Reynolds2005) and prolonged grief or PGD (Prigerson et al., Reference Prigerson, Maciejewski, Reynolds, Bierhals, Newsom, Fasiczka and Miller1995b, Reference Prigerson, Horowitz, Jacobs, Parkes, Aslan, Goodkin and Maciejewski2009) and both require that at least 6 months should have elapsed since the death before a diagnosis can be made. We use prolonged grief thereafter except when we are referring to specific criteria proposed for this condition. In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-fifth edition (DSM-5), a new category for persistent complex bereavement-related disorder (PCBD) was included under the ‘conditions for further study’ section requiring symptoms to persist for at least 12 months. We have previously evaluated the performance of the PCBD criteria in bereaved children and found that the criteria only identified 20–41.7% of children with trajectories of grief that were high and sustained for nearly 3 years after sudden parental death (Melhem, Porta, Walker Payne, & Brent, Reference Melhem, Porta, Walker Payne and Brent2013). Studies in adults evaluating the PCBD criteria found them to correctly identify 47–82% of cases in community and clinical samples of adults and reported that revisions of these criteria to emphasize the core symptoms of yearning/longing and/or preoccupation with the deceased and 1 or 2 of the associated symptoms (Criterion C) improved its performance (Cozza et al., Reference Cozza, Fisher, Mauro, Zhou, Ortiz, Skritskaya and Shear2016, Reference Cozza, Shear, Reynolds, Fisher, Zhou, Maercker and Ursano2019; Mauro et al., Reference Mauro, Shear, Reynolds, Simon, Zisook, Skritskaya and Glickman2017). In the Yale Bereavement Study, PCBD and PGD, and CG criteria performed similarly with high sensitivity ranging between 83.3% and 100% and high specificity ranging between 78.6% and 98.3% (Maciejewski, Maercker, Boelen, & Prigerson, Reference Maciejewski, Maercker, Boelen and Prigerson2016). However, these studies were cross-sectional or used a cross-sectional determination of caseness. In this paper, we examined the performance of the DSM-5 PCBD criteria in adults bereaved by sudden death to identify prolonged grief cases as determined prospectively consistent with our approach in children. We also assess the dimensional approach in identifying adults with prolonged grief.

Methods

Sample

Primary caregivers of offspring who lost a parent (or proband thereafter) to suicide, accident, or sudden natural deaths were recruited (n = 138). The caregivers were either a spouse or significant other to the deceased (65.3%), divorced or separated spouse (18.0%), or other relatives (16.7%, e.g. mother, sibling). Participants were interviewed at baseline, which occurred on average 8 (standard deviation (s.d.) = 3.6) months after the death. The majority of the sample was females (89.1%) with mean age of 44.2 years (s.d. = 8.3, range 27–71). The 138 caregivers came from 135 families who were interviewed at baseline and followed up at 21 (s.d. = 3.8) months; 32 (s.d. = 3.7) months, 67 (s.d. = 11.8), and 90 months (s.d. = 11.8) after the death. The follow-up retention rates were 100% (n = 138), 96.4% (n = 133), 85% (n = 117), 71% (n = 98) at 21, 32, 67, and 90 months, respectively. There were no differences between participants lost to follow-up and those retained in their rates of lifetime history of psychiatric disorders prior to the death, new-onset psychiatric disorders following the death, and functional impairment. However, those lost to follow-up were more likely to be males [37.5% v. 11.2%, Fisher's exact test (FET) p = 0.01].

Recruitment

Details regarding the recruitment and representativeness of the sample have been previously published (Brent, Melhem, Donohoe, & Walker, Reference Brent, Melhem, Donohoe and Walker2009; Melhem et al., Reference Melhem, Moritz, Walker, Shear and Brent2007; Melhem, Walker, Moritz, & Brent, Reference Melhem, Walker, Moritz and Brent2008; Melhem et al., Reference Melhem, Porta, Shamseddeen, Walker Payne and Brent2011). In brief, we sought bereaved families in which the deceased probands were between the ages of 30 and 60, had biological children aged 7–18 years old, and had died within 24 h from suicide (n = 47), accident (n = 31), or sudden natural death (n = 57). Accidents in which multiple family members died or were seriously injured were excluded. Methods of recruitment included monthly reports, between July 2002 and December 2006, from the medical examiner (ME) offices of Allegheny County and neighboring counties (41.9%); and newspaper advertisement (54.8%). An approval from the Institutional Review Board at the University of Pittsburgh was obtained. Sudden natural deaths were mostly (70.2%) recruited through advertisement because they were unlikely to come to the attention of the ME and included cases of myocardial infarction (n = 27), other heart conditions (n = 12), infections (n = 4), cancer (n = 5), and other causes (n = 9) (e.g. stroke, gastric bypass surgery). The accidental deaths consisted of 12 drug overdoses, 12 motor vehicle accidents, five blunt force trauma, and two deaths from drowning. Drug overdoses were evaluated to exclude those with likely suicidal intent. Probands who died from drug overdoses had no previous history of suicide attempts as compared to those who died by suicide (0% v. 29.8%, FET, P = 0.05). Probands recruited through the ME's office and those recruited by advertisement were similar except that those recruited through the ME had higher rates of anxiety (31.9% v.14.7%, χ2 = 4.92, df = 1, p = 0.03) and alcohol/substance use disorders (76.8% v. 47.1%, χ2 = 11.35, df = 1, p = 0.001).

Assessment

Interviews were conducted at the participant's homes or in our offices by master's level interviewers with a background in psychology or social work who received extensive training on the interviews. Current and previous history of psychiatric disorders was assessed using the Structured Interview for DSM-IV Axis I and II Disorders (SCID) (First, Spitzer, Gibbon, Williams, & Benjamin, Reference First, Spitzer, Gibbon, Williams and Benjamin1994). At follow-up, the SCID was used in conjunction with the longitudinal interval follow-up evaluation (LIFE) (Keller et al., Reference Keller, Lavori, Friedman, Nielsen, Endicott, McDonald-Scott and Andreasen1987) to assess the longitudinal course of psychiatric disorders. Functional impairment was rated by the clinician based on the psychiatric interview using the global assessment scale (GAS) (Endicott, Spitzer, Fleiss, & Cohen, Reference Endicott, Spitzer, Fleiss and Cohen1976). Lower scores on the GAS correspond to worse impairment. High inter-rater reliability was maintained on psychiatric diagnoses and global impairment (Kappa ranged between 0.61 and 0.88 for SCID; ICC = 0.85 for GAS).

We used the 19-item inventory for complicated grief (ICG) (Prigerson et al., Reference Prigerson, Frank, Kasl, Reynolds, Anderson, Zubenko and Kupfer1995a) to assess grief reactions. A total score of 25 or higher has been previously used as a cut-off to identify participants with prolonged grief reactions (Prigerson et al., Reference Prigerson, Maciejewski, Reynolds, Bierhals, Newsom, Fasiczka and Miller1995b). The circumstances of exposure to death (CED), a semi-structured interview was used to assess the participant's experience surrounding and following the death of the proband (Brent et al., Reference Brent, Perper, Moritz, Allman, Roth, Schweers and Balach1993). A history of physical or sexual abuse was assessed using screens from the post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) section of the psychiatric interview and the Abuse Dimensional Inventory (Chaffin, Wherry, & Newlin, Reference Chaffin, Wherry and Newlin1997).

Self-reported symptoms of depression, anxiety, PTSD, and suicidal ideation were assessed using the beck depression inventory, the beck anxiety inventory, the PTSD symptom scale-interview (PSSI-I), and the suicide ideation questionnaire, respectively (Beck, Ward, Mendelson, Mock, & Erbaugh, Reference Beck, Ward, Mendelson, Mock and Erbaugh1961; Beck, Epstein, Brown, & Steer, Reference Beck, Epstein, Brown and Steer1988; Foa, Johnson, & Feeny, Reference Foa, Johnson and Feeny1993; Reynolds, Reference Reynolds1991). Hopelessness was assessed using the beck hopelessness scale (Beck, Weissman, Lester, & Trexler, Reference Beck, Weissman, Lester and Trexler1974). Socioeconomic status and household income were rated using Hollingshead's scale (Hollingshead, Reference Hollingshead1975). We also assessed intercurrent life events using the social readjustment rating scale (Holmes & Rahe, Reference Holmes and Rahe1967); family cohesion using the family adaptability and cohesion evaluation scales-II (Olsen, Portner, & Lavee, Reference Olsen, Portner and Lavee1985); social support using the multidimensional scale of perceived social support (Zimet, Dahlem, & Zimet, Reference Zimet, Dahlem and Zimet1988); aggression using the Aggression Questionnaire (Buss & Perry, Reference Buss and Perry1992); self-esteem using the Weinberger Adjustment Inventory self-esteem subscale (Weinberger, Feldman, Ford, & Chastain, Reference Weinberger, Feldman, Ford and Chastain1987); coping style using the Ways of Coping Questionnaire (Lazarus, Reference Lazarus1993); guilt using the self-blame scale (Foa, Ehlers, & Clark, Reference Foa, Ehlers and Clark1999); the nature of the relationship with the deceased using the Psychosocial Schedule (Puig-Antich et al., Reference Puig-Antich, Kaufman, Ryan, Williamson, Dahl, Lukens and Nelson1993); and locus of control using the Lumpkin Scale (Lumpkin, Reference Lumpkin1985). A questionnaire about physical health was also administered using the adapted Krause Health History Questionnaire (Krause, Reference Krause1998), which included questions about history of chronic illness and medications use, and a subjective rating of their overall health prior and after the death with 1 to 4 score corresponding to poor, fair, good, and excellent, respectively.

Assessment of PCBD criteria

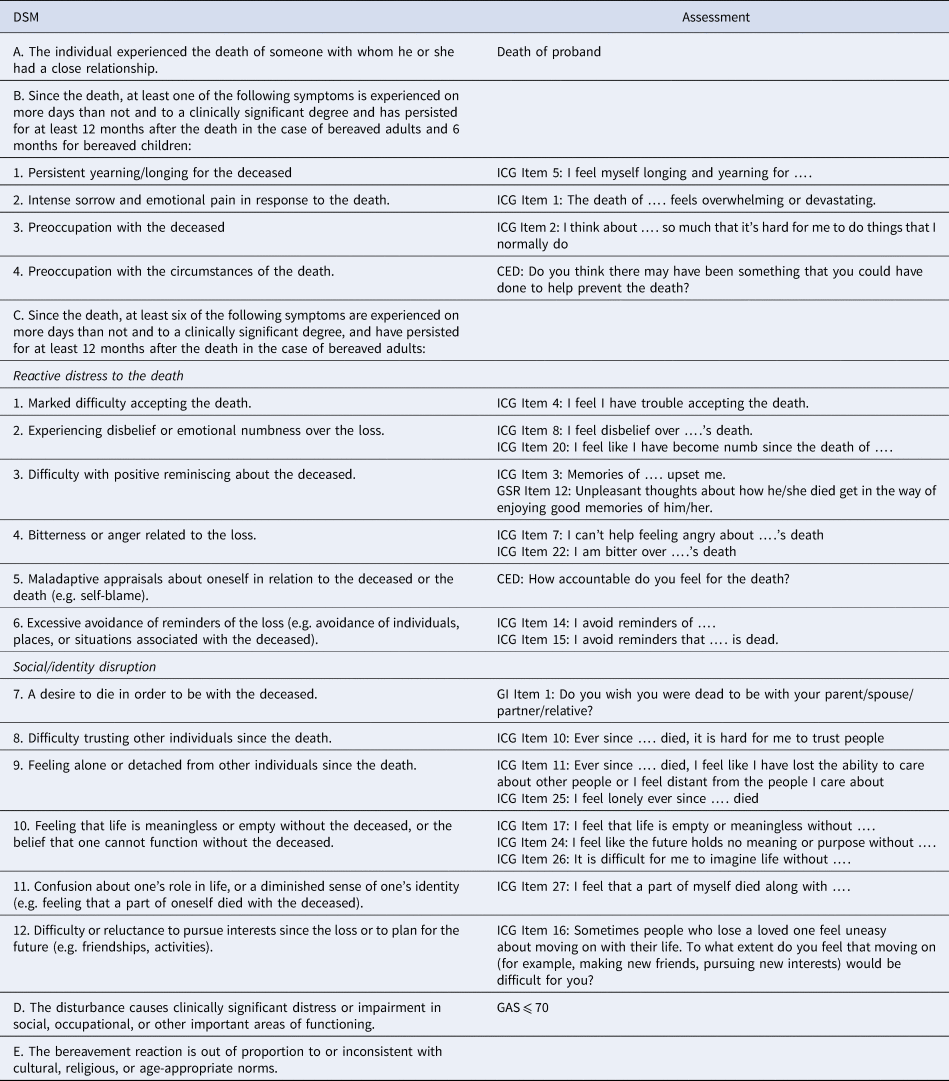

Table 1 presents the proposed DSM-5 criteria for PCBD and the corresponding assessment items that we evaluated using the following five sources: ICG; CED; grief interview (GI); grief self-report (GSR) and GAS. The GI and GSR included questions that were not assessed in the ICG, such as having unpleasant thoughts about the death preventing positive memories or a desire to die to be with the deceased. Criterion A of the proposed DSM-5 PCBD criteria stipulates that at least 12 months must have elapsed since the bereavement. Participants were assessed at baseline 8 months following bereavement on average, and as such, we limit our examination of the proposed criteria to subsequent interviews at 21, 32, 67, and 90 months. Criteria B and C require that the participant experiences on more days than not at least 1 and 6 of the proposed symptoms, respectively. Using the ICG, CED, GI, and GSR, we used a cut-off of ⩾4 (endorsing the given symptom often or always) on individual items to determine positive responses on the corresponding suggested PCBD item. We used a GAS cut-off score of 70 to determine whether participants met criterion D, corresponding to significant functional impairment.

Table 1. Proposed DSM-5 criteria for persistent complex bereavement-related disorder

ICG, inventory for complicated grief; GSR, grief self-report; CED, circumstances of exposure to death; GI, grief interview.

Statistical analysis

In order to examine the sensitivity and specificity of the proposed DSM-5 criteria in identifying cases of CG, we first conducted latent class growth analysis (LCGA) on the ICG to identify trajectories. We started with a one-class model, and then increased the number of classes until we reached the best fitting model using goodness of fit statistics, Bayesian information criteria, and the Lo-Mendell-Rubin adjusted likelihood ratio test. The best-fitting model resulted in three classes (Fig. 1). We used paired t tests to examine differences in ICG scores between 8 and 21 months, 21 and 32 months, 32 and 67 months, and between 97 and 90 months. We used analysis of variance (ANOVA) to compare ICG scores between the resulting trajectories or classes at 8, 21, 32 67, and 90 months.

Fig. 1. Grief trajectories using latent class growth curve analysis.

To validate the trajectory that corresponded to prolonged grief, we examined the baseline predictors of these trajectories and the relationship of the resulting trajectories with functional impairment, as measured by the GAS, over time. We compared the resulting grief trajectories on baseline demographic, clinical, and psychosocial characteristics using χ2 test, Fisher's exact test, and ANOVA. All tests were two-tailed. To correct for multiple comparisons, we used the false discovery rate (FDR) with the Yekutieli multiple test procedure, which takes into account the correlation between covariates (Benjamini & Yekutieli, Reference Benjamini and Yekutieli2001). We used a significance level of <0.05 for FDR q value. Post-hoc pairwise analyses between the three classes were conducted only after a statistically significant q value and corrected for multiple comparisons with Bonferroni correction (α = 0.05/3 = 0.017). Variables significantly associated with ICG trajectories were introduced in a multinomial logistic regression to identify the most parsimonious set of predictors. We used the hierarchical method with blocks introduced in the order in which they are listed: (1) characteristics antecedent to the death including circumstances of exposure to death (e.g. type of death), (2) new-onset diagnoses following the death, (3) self-reported symptoms and psychosocial characteristics, and (4) physical health profile. We controlled for time between death and baseline interview. We removed variables from the final model if they were not significant at p < 0.05. We also tested for two-way interactions between variables with significant main effects. We applied multiple imputation by chained equations (MICE) technique in STATA (ice) for missing data with an inclusive strategy as recommended by Collins and Colleagues (Collins, Schafer and, & Kam, Reference Collins, Schafer and and Kam2001). In all, 23% of participants had missing data on 2 variables and 36.2% on 3 or more variables. Multinomial logistic regression was conducted on the original and an imputed dataset. Similar results were obtained and hence, we report here results from the imputed dataset.

To examine the relationship of the resulting trajectories with functional over time, we used mixed effects regression analysis including main effects for time, class, and a class × time interaction. We also controlled for covariates that were significantly associated with functional impairment.

To examine the PCBD criteria, we used receiver operator characteristics (ROC) analyses with the number of criteria B and C items that met the ⩾4 cut-off criterion to discriminate the prolonged grief trajectory. We also used ROC analyses to identify the sensitivity and specificity for the dimensional approach using the ICG at each timepoint in discriminating the prolonged grief trajectory. Data analysis was performed using STATA 11.2 (StataCorp, 2009).

Results

Grief trajectories

Using LCGA, we identified three distinct classes or trajectories for grief reactions (Fig. 1). Participants in Class 1 (n = 73, 53%) had an average ICG score of 10.2 (s.d. = 6.2) at baseline (Table 2). ICG scores for participants in Class 1 were low at 21 months and remained low afterwards. Class 2 (n = 46, 33%) showed an average ICG score of 24.9 (s.d. = 8.9) at baseline and showed a significant decrease starting at 32 months (q = 0.04) following the death. Class 3 (n = 19, 14%) showed an average baseline ICG score of 41.8 (s.d. = 12.3), which did not significantly decrease over time, consistent with prolonged grief reactions. Significant differences were found in ICG scores in pairwise comparisons among the three trajectories at each timepoint with q < 0.001 (Table 2).

Table 2. ICG scores at baseline and follow-up by grief trajectories 2

a, b, and c superscripts refer to significant post-hoc comparisons.

*KW: Kruskal–Wallis non-parametric test.

We next examined the baseline demographic, clinical, and psychosocial characteristics as predictors of the grief trajectories to further validate the prolonged grief trajectory. There were no statistically significant differences between the three classes on demographic characteristics, type of death, relationship to the deceased, history of psychiatric disorders, and health and psychosocial profile prior to the death (see online Supplementary Table S1). Class 2 and 3 were similar on their rates of new-onset depression and PTSD developed within 8 months of the death and higher compared to rates in Class 1. However, participants in Class 3 showed higher scores on self-reported symptoms of depression, anxiety, PTSD, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation compared to those in Classes 1 and 2. They also showed more functional impairment, lower family adaptability and cohesion, lower self-esteem, and higher aggression compared to those in Classes 1 and 2. To identify the most parsimonious set of predictors, we introduced variables significantly differentiating grief trajectories in a hierarchical multinomial logistic regression. Controlling for months since the death, higher self-reported depression symptoms at baseline or 8 months following the death significantly differentiated Class 3 from Class 1 (RRR = 1.21, 95% CI 1.09–1.36, p = 0.001) and Class 2 from Class 1 (RRR = 1.13, 95% CI 1.04–1.22, p = 0.003) (Table 3). New-onset PTSD within 8 months of the death significantly differentiated Class 2 only from Class 1 (RRR = 7.33, 95% CI 1.87–28.67, p = 0.004) and functional impairment significantly differentiated Class 3 only from Class 1 (RRR = 0.82, 95% CI 0.70–0.97, p = 0.02).

Table 3. Multinomial logistic regression with the final parsimonious model predicting ICG class

a Relative risk ratio.

b Confidence Interval.

c Class 1 is the reference group.

d Lower scores correspond to worse functional impairment.

We then examined the relationship of grief trajectories with functional impairment longitudinally using mixed effects regression, we found participants in Class 3 (β = −12.85, 95% CI −18.71 to −6.99; p < 0.001) to show worse impairment at each follow-up followed by those in Class 2 (β = −6.02, 95% CI −9.74 to −2.29, p = 0.002). There was no significant main effect for time nor a significant Class × time interaction. Although Class 2 was associated with functional impairment, we defined prolonged grief cases as those belonging to Class 3 because they showed on average a score ⩾25 at each timepoint that did not decrease over time and showed higher functional impairment at baseline and each timepoint.

Evaluation of DSM-5 PCBD criteria

PCBD criteria correctly identified 94.7%, 84.2%, 63.2%, and 57.9% of cases at 21, 32, 67, and 90 months, respectively. The criteria showed perfect specificity (100%) at all timepoints; however, its sensitivity was low except for the 32 months timepoint with 5.6% at 21 months, 81.3% at 32 months, 25% at 67 months, and 27.3% at 90 months. We then tested different thresholds for the number of symptoms required for Criterion C and found meeting 3 or more as opposed to at least 6 of the 12 proposed symptoms to improve the PCBD's overall sensitivity to 89.5%, 94.1%, 75%, and 45.5% at 21, 32, 67, and 90 months, respectively. The specificity continued to be high ranging between 98% and 100% at all timepoints. At 90 months, the sensitivity of the PCBD criteria improved to 63.6% using 2 or more symptoms as the threshold for meeting criterion C.

Evaluation of the dimensional approach

Using ROC analysis, the ICG with a cut-off score of 25 or more discriminated Class 3 from Classes 1 and 2, combined, with high sensitivity (sens) and specificity (spec) at 8 (sens = 0.944, spec = 0.787), 21 (sens = 1, spec = 0.873), 32 (sens = 1, spec = 0.927), 67 (sens = 0.769, spec = 0.97), and 90 (sens = 0.50, spec = 0.989) months following the death. (Table 4) As the ICG scores in Classes 1 and 2 declined and those in Class 3 remained high, the specificity in discriminating Class 3 from Classes 1 and 2 improved significantly from 0.787 at 8 months to 0.872 at 21 months (p = 0.03), 0.927 at 32 months (p < 0.001), 0.97 at 67 months (p < 0.001), and 0.99 at 90 months (p < 0.001).

Table 4. Cut-off of the inventory of complicated grief

Discussion

We found that the proposed DSM-5 criteria for PCBD correctly identified 57.9–94.7% of cases with prolonged grief determined prospectively in our sample of adult caregivers bereaved by sudden deaths, with perfect specificity and low to high sensitivity ranging from 5.6% to 81.3%. In contrast, the dimensional approach resulted in higher sensitivity and specificity. Using three or more symptoms as the threshold to meet criterion C improved the PCBD overall's sensitivity at all timepoints.

We discuss the results of this study in the context of its strengths and limitations. This is the first study to evaluate the proposed DSM-5 PCBD criteria in adults using a case definition based on the longitudinal course of grief using data extending up to 7.5 years after the death. However, there were several limitations. It is difficult to determine the representativeness of the sample with potential referral biases from advertisement sources where participants experiencing more discomfort following bereavement could be more likely to participate in the study. We found probands whose families were recruited from advertisement and ME's records to be similar except for lower rates of lifetime alcohol and substance use disorders in the advertisement group, which argues against such a referral bias. Participants lost to follow-up and those retained in the study were not significantly different on grief scores. Our results are limited to those bereaved by sudden deaths and may not be generalizable to those bereaved by homicide or anticipated causes of deaths. Finally, the lack of ethnic diversity in our sample limits the generalizability of these results to non-Caucasians.

In this study, we applied LCGA to determine cases of prolonged grief. The trajectory of prolonged grief consisted of 13% of adults bereaved by sudden death, consistent with prevalence rates reported in prior studies of adult and child samples (Bonanno et al., Reference Bonanno, Wortman, Lehman, Tweed, Haring, Sonnega and Nesse2002; Melhem et al., Reference Melhem, Porta, Shamseddeen, Walker Payne and Brent2011; Middleton, Raphael, Burnett, & Martinek, Reference Middleton, Raphael, Burnett and Martinek1998; Prigerson et al., Reference Prigerson, Maciejewski, Reynolds, Bierhals, Newsom, Fasiczka and Miller1995b, Reference Prigerson, Horowitz, Jacobs, Parkes, Aslan, Goodkin and Maciejewski2009). Our findings are also consistent with those from a sample of bereaved Swedish tourists who survived the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunamis where a similar statistical approach identified three similar trajectories (Sveen, Bergh Johannesson, Cernvall, & Arnberg, Reference Sveen, Bergh Johannesson, Cernvall and Arnberg2018). Similar to our model, 11% of the participants in the Swedish sample were found to have prolonged grief. We further validated the prolonged grief trajectory by examining its predictors and relationship with functional impairment compared to other trajectories. Functional impairment within 8 months of the death predicted the prolonged grief trajectory; conversely, participants in the prolonged grief consistently showed worse functional impairment throughout follow-up compared to the other trajectories. These results are consistent with prior studies showing prolonged grief reactions to be associated with functional impairment even after controlling for comorbid diagnoses, including depression, anxiety, and PTSD (Melhem et al., Reference Melhem, Rosales, Karageorge, Reynolds, Frank and Shear2001, Reference Melhem, Moritz, Walker, Shear and Brent2007, Reference Melhem, Porta, Shamseddeen, Walker Payne and Brent2011). In other studies, ICG scores 3–6 months after the death were also found to predict enduring impairment in global functioning (Prigerson et al., Reference Prigerson, Frank, Kasl, Reynolds, Anderson, Zubenko and Kupfer1995a).

We found the DSM-5 PCBD criteria to be highly specific for the identification of prolonged grief, however, they are not sensitive enough and could lead to false negatives. Our results also show that revising criterion C to a less stringent threshold of ⩾3 symptoms rather than the proposed ‘at least 6 symptoms’ greatly improved the sensitivity of the proposed PCBD criteria. As such, we note that the proposed PCBD criteria might be overly restrictive and may exclude cases with clinically significant grief-related distress and impairment. These results are consistent with Cozza et al. (Reference Cozza, Fisher, Mauro, Zhou, Ortiz, Skritskaya and Shear2016) findings where they similarly reported the PCBD criteria to have high specificity (99.9%) and low sensitivity (53.3%). Similar conclusions were also reached by Mauro et al. (Reference Mauro, Shear, Reynolds, Simon, Zisook, Skritskaya and Glickman2017) and Cozza et al. (Reference Cozza, Shear, Reynolds, Fisher, Zhou, Maercker and Ursano2019) where endorsing 1 or 2 symptoms improved the performance of the PCBD criteria. These results are not consistent with Maciejewski et al.'s findings showing high sensitivity and specificity for PCBD criteria in a longitudinal community-based study of bereaved individuals. Our study is unique in evaluating the proposed criteria prospectively, which should result in increased specificity as grief reactions subside over time in non-cases and continue to be increased in cases. In this study, we found the dimensional approach using the ICG to identify individuals at risk for prolonged grief early on following bereavement, similar to our results in children (Melhem et al., Reference Melhem, Porta, Walker Payne and Brent2013). While the clinical utility of the categorical and dimensional approaches is debated in other psychiatric disorders (Bornstein, Reference Bornstein2019; McCabe & Widiger, Reference McCabe and Widiger2019; Widiger, Reference Widiger2019), we consider both approaches to be complimentary. Clinicians and researchers need to keep in mind that whatever criteria for prolonged grief will be adopted or adapted in the DSM system, there will be heterogeneity in symptom presentation and prognosis between individuals (Melhem & Brent, Reference Melhem and Brent2019). Our results and those by Mauro et al. (Reference Mauro, Shear, Reynolds, Simon, Zisook, Skritskaya and Glickman2017) and Cozza et al. (Reference Cozza, Shear, Reynolds, Fisher, Zhou, Maercker and Ursano2019) propose revisions to the PCBD criteria that emphasize the core symptoms of prolonged grief and will probably reduce the heterogeneity between individuals meeting criteria for the same condition.

While there are tools for the identification and treatment of prolonged grief in adults (Shear et al., Reference Shear, Frank, Houck and Reynolds2005); efforts should be made to make these tools available to the practicing clinician for the relief of grief in bereaved individuals. There is accumulating evidence that prolonged grief responds to specific treatments such as complicated grief treatment, and not to treatments for depression such as antidepressants or interpersonal therapy (Shear et al., Reference Shear, Frank, Houck and Reynolds2005, Reference Shear, Wang, Skritskaya, Duan, Mauro and Ghesquiere2014, Reference Shear, Reynolds, Simon, Zisook, Wang, Mauro and Skritskaya2016). These results highlight the importance for clinicians to be aware of prolonged grief as an impairing condition separate from, though frequently comorbid with depression and the importance for researchers to widely disseminate specific treatment approaches to reduce the burden of prolonged grief.

In conclusion, we recommend the revision of the proposed PCBD criteria in order to improve the identification of individuals with prolonged grief and hopefully, help them to seek and receive evidence-based treatment. Clinicians also need to monitor grief symptoms over time using already available dimensional approaches.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291719003829

Acknowledgements

We want to thank all families who have participated in the study. This study work was supported by an R01 grant (MH65368, Brent DA) and a K01 grant (MH077930, Melhem NM) from the National Institute of Mental Health; and a Young Investigator Award from the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (Melhem NM). The National Institute of Mental Health and the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention did not participate in the design and conduct of the study; in the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

Elie G. Aoun and Giovanna Porta report no competing interests. Dr Melhem receives support from NIMH and AFSP. Dr Brent receives research support from NIMH, AFSP, the Once Upon a Time Foundation, and the Beckwith Foundation, receives royalties from Guilford Press, from the electronic self-rated version of the C-SSRS from eRT, Inc., and from performing duties as an UptoDate Psychiatry Section Editor, receives consulting fees from Healthwise, and receives Honoraria from the Klingenstein Third Generation Foundation for scientific board membership and grant review.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the Institutional Review Board for human subject protection at the University of Pittsburgh.