Introduction

Bipolar disorder (BD) causes significant disability in personal and social domains, and with a prevalence of 1–2% (Merikangas et al. Reference Merikangas, Akiskal, Angst, Greenberg, Hirschfeld, Petukhova and Kessler2007), it imposes a huge burden on society. According to a recent meta-analysis, patients with BD spend more than 40% of their time ill (Forte et al. Reference Forte, Baldessarini, Tondo, Vazquez, Pompili and Girardi2015). Despite the fact that it is possible to control the symptoms of BD using medication, low levels of adherence is a substantial problem and have been reported in up to 50% of cases (Lacro et al. Reference Lacro, Dunn, Dolder, Leckband and Jeste2002; Lingam & Scott, Reference Lingam and Scott2002; Scott & Pope, Reference Scott and Pope2002a , Reference Scott and Pope b ; Geddes & Miklowitz, Reference Geddes and Miklowitz2013). Patients with BD show a much lower rate of routinely and consciously taking prescribed medicines (35%) than patients with, for example, schizophrenia (50–60%). Consequently, patients with BD tend to have poorer health outcomes, including lower levels of daily functioning, psychological health, and quality of life (QoL) (Dean et al. Reference Dean, Gerner and Gerner2004; IsHak et al. Reference IsHak, Brown, Aye, Kahloon, Mobaraki and Hanna2012). Therefore, it is important to develop interventions that can promote medication adherence (MA).

Effective interventions are likely to be those that target modifiable determinants of non-adherence (Berk et al. Reference Berk, Berk and Castle2004), such as beliefs and attitudes (Lingam & Scott, Reference Lingam and Scott2002; Scott & Pope, Reference Scott and Pope2002a ; Berk et al. Reference Berk, Berk and Castle2004). As a result, a few studies (Bauer et al. Reference Bauer, McBride, Williford, Glick, Kinosian, Altshuler, Beresford, Kilbourne and Sajatovic2006a , Reference Bauer, McBride, Williford, Glick, Kinosian, Altshuler, Beresford, Kilbourne and Sajatovic b ; Cakir et al. Reference Cakir, Bensusan, Akca and Yazici2009; Javadpour et al. Reference Javadpour, Hedayati, Dehbozorgi and Azizi2013) have designed behavioral interventions (e.g. behavioral therapy, family reliant treatments, psychosocial education, and interpersonal therapies) in an effort to promote MA. For example, Parsons et al. used behavioral therapy to improve MA in HIV-positive people and found reductions in substance abuse (although no significant change in MA, perhaps due to the relatively small sample (Folco et al. Reference Folco, Lee, Dufu, Yamazaki and Reed2012). In another study on BD patients, eight sessions of psychoeducation yielded better MA and also QoL among participants in the intervention group when followed up 2 years later (Javadpour et al. Reference Javadpour, Hedayati, Dehbozorgi and Azizi2013). Other interventions designed to promote MA have focused on increasing communication and support provided by family members to patients, and this strategy is popular for the treatment of mental disorders such as schizophrenia (Rollnick et al. Reference Rollnick, Miller, Butler and Aloia2008).

However, previous studies that have addressed the challenge of MA in patients with BD have been somewhat limited in their methods. To the best of our knowledge, all previous studies have only used one type of intervention (namely, psychoeducation) in addition to usual care (Rouget & Aubry, Reference Rouget and Aubry2007). The beneficial effects of psychoeducation for patients with BD have been demonstrated on a number of different outcomes, including MA, insight improvement, and a reduction in symptoms relief for people with BD (Rouget & Aubry, Reference Rouget and Aubry2007; Bilderbeck et al. Reference Bilderbeck, Atkinson, McMahon, Voysey, Simon, Price, Rendell, Hinds, Geddes, Holmes and Miklowitz2016; Hidalgo-Mazzei et al. Reference Hidalgo-Mazzei, Mateu, Reinares, Murru, del Mar Bonnín, Varo, Valentí, Undurraga, Strejilevich, Sánchez-Moreno and Vieta2016; Kallestad et al. Reference Kallestad, Wullum, Scott, Stiles and Morken2016). Similar interventions have also been shown to reduce the burden of care, as well as distress among family members (Bermúdez-Ampudia et al. Reference Bermúdez-Ampudia, García-Alocén, Martínez-Cengotitabengoa, Alberich, González-Ortega, Resa and González-Pinto2016; Hubbard et al. Reference Hubbard, McEvoy, Smith and Kane2016). Given that patients with BD can differ in their responses to the same intervention (Culpepper, Reference Culpepper2014), it is possible that a multifaceted intervention that targets various reasons for non-adherence might result in even better outcomes.

A second problem with the evidence-base to date is that many (but not all) previous studies (Bauer et al. Reference Bauer, McBride, Williford, Glick, Kinosian, Altshuler, Beresford, Kilbourne and Sajatovic2006b ; Cakir et al. Reference Cakir, Bensusan, Akca and Yazici2009; Javadpour et al. Reference Javadpour, Hedayati, Dehbozorgi and Azizi2013) have primarily used self-reported questionnaires to measure MA. However, self-reported outcomes may be biased by social desirability effects (e.g. patients with BD may feel obligated to report that they have followed the instructions of a health professional) and/or memory problems (e.g. patients with BD may not remember whether they have taken their medication). Using objective measures of adherence, such as serum levels of mood stabilizers, can reduce the possibility of bias and provide a more accurate estimate of the effect of an intervention on MA.

The present research

Given the importance of developing interventions to promote MA among people with BD and the limitations of the current evidence, the present research sought to develop a multifaceted intervention and examine the effects of the intervention on self-report and objective indices of MA, as well as secondary outcomes that include potential mediators of treatment effects. The intervention was centered around motivational interviewing (MI), a client-centered approach that seeks to change attitudes and behavior (Lundahl et al. Reference Lundahl, Moleni, Burke, Butters, Tollefson, Butler and Rollnick2013). Although originally developed for reducing alcohol dependence, the use of MI has been rapidly expanded to other health-related domains. Indeed, a meta-analysis of 48 studies has shown that MI is an effective way to promote changes in behavior across multiple healthcare domains such as diabetes, obesity, smoking, and HIV treatment (Lundahl et al. Reference Lundahl, Moleni, Burke, Butters, Tollefson, Butler and Rollnick2013). In recent years, MI has also been used to improve MA in conditions that require long-term commitment to treatment such as schizophrenia and acute coronary syndrome (Depp et al. Reference Depp, Lebowitz, Patterson, Lacro and Jeste2007). Nevertheless, there is scant evidence on the effect of MI in improving MA in patients with BD.

In addition to MI, we also investigated the idea that interventions might benefit from including family members, because family members are likely to support patients with BD in taking their medications (Williams & Wright, Reference Williams and Wright2014) especially in the East, where culture substantially values the family relationship (Tsai et al. Reference Tsai, Strong and Lin2015).

Despite the importance of MA (or lack thereof) in patients with BD, a systematic review of studies testing the efficacy of interventions designed to improve MA in BD found only five studies whose primary outcome was adherence. A meta-analysis of 18 studies showed an OR of 2.27 (95% CI 1.45–3.56) for improvement in adherence in the intervention group compared with control groups (MacDonald et al. Reference MacDonald, Chapman, Syrett, Bowskill and Horne2016).To the best of our knowledge, our study is the most comprehensive study to date of a multifaceted intervention to improve the adherence in patients with BD.

Methods

Design and study population

A multicenter, randomized, observer-blind, controlled, parallel-group trial was conducted in ten academic centers in Iran: Tehran (three centers), Qazvin, Ahvaz, Semnan, Zanjan, Tabriz, Zahedan, and Mashahd between September 2014 and October 2016. Persian speaking patients were eligible if they: (1) met the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR) criteria for bipolar I or II disorders simultaneously confirmed by the administration of Structured Clinical Interview (SCID); (2) were 18 years or older; (3) were being treated with a mood stabilizer; and (4) were not attending weekly or biweekly psychotherapy. Patients were excluded if they: (1) had a DSM-IV-TR diagnosis of drug or alcohol misuse disorders (five independent researchers administered a semi-structured interview and a structured interview based on DSM-IV-TR criteria for alcohol abuse, alcohol dependence and also substance abuse excluding nicotine); (2) showed evidence of severe DSM-IV-TR borderline personality; (3) needed to change the type and/or the dose of a mood stabilizer; (4) were pregnant or planned to be pregnant in the next year; (5) were unable and/or unwilling to provide a written informed consent; (6) had any organic cerebral cause for BD (e.g. multiple sclerosis or stroke); or (7) had an intellectual disability. Figure 1 shows the flow of participants through the trial, including the number of patients excluded for the various reasons detailed above.

Fig. 1. Flow of participants through the trial.

All patients and their family members provided informed consent before participating in the study. The protocol was prepared in accordance with the Ottawa Statement, the Helsinki Declaration and Good Clinical Practice, and ethical review committees at each of the sites approved the trial. The trial was registered in the clinicaltrials.gov registry (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02241863).

Intervention

A multifaceted intervention was developed in an effort to improve MA and clinical outcomes. The intervention included two components: (a) Psychoeducation for the patients and their family members and (b) Miller & Rollnick (Reference Miller and Rollnick2012). Detailed information on the intervention is provided in the online Supplementary Materials.

MI integrity/fidelity

To assess treatment fidelity, all sessions were recorded and transcribed. Two trained research assistants reviewed each recording in order to determine the proportion of the intervention elements that were covered by the facilitators. The Motivational Interview Treatment Integrity (MITI) scale was used to assess the integrity of the MI in the EXP group. Two separate aspects of treatment fidelity were taken into account: (i) Global variables (i.e. empathy, evocation, collaboration, autonomy/support, and direction) and (ii) behavior counts (i.e. giving information, asking open-ended and closed-ended questions, providing simple and complex reflections, and making other statements categorized as MI adherent or not). Inter-rater reliability was computed using intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) in a two-way mixed model with absolute agreement. The ICCs were found to be adequate for global measures, behavior counts, and summary scores (ICCs ranged from 0.69 to 0.92, as reported in online Supplementary Table S1).

Usual care

Patients in the usual care (UC) group received the usual care that is provided to people with severe mental illnesses in Iran, which is mainly based on pharmacological interventions and follow-up visits to address and deal with adjustments to the dosage and/or nature of medications and management of side effects. There are no national guidelines for the provision of psychosocial services such as occupational rehabilitation, supported employment, social skills education, and family support. However, during last decade, there has been a growing interest in providing these services, such that informal psycho-education about social skills and compliance with treatment may be provided on some occasions.

Outcomes

The primary outcome measure was MA measured using self-report and objective indices. Secondary outcomes included measures of beliefs and psychosocial health. All outcomes were measured three times (at baseline before the intervention, and then 1 and 6 months after the intervention) using the measures described below. Clinical status was assessed using the Clinical Global Impressions-Bipolar-Severity of Illness (CGI-BP-S; (Spearing et al. Reference Spearing, Post, Leverich, Brandt and Nolen1997) and the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS; Young et al. Reference Young, Biggs, Ziegler and Meyer1978) and the Montgomery Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS; Montgomery & Asberg, Reference Montgomery and Asberg1979) were used to assess manic and depressive symptoms, respectively. The clinical measures were administrated by five psychiatrists who were blinded to the treatment allocation.

Medication Adherence Rating Scale (MARS)

The MARS was used to measure the primary outcome in the study; namely, MA. Patients were asked to rate the extent to which five statements describing non-adherent behaviors, such as forgetting to take medicines or missing a dose, apply to them on a 5-point Likert scale (1: Always to 5: Never), e.g. Do you ever forget to take your medication? (O'Carroll et al. Reference O'Carroll, Whittaker, Hamilton, Johnston, Sudlow and Dennis2011). The MARS has been shown to be relatively unaffected by social desirability effects (O'Carroll et al. Reference O'Carroll, Whittaker, Hamilton, Johnston, Sudlow and Dennis2011), and the Persian translation of the MARS (Pakpour et al. Reference Pakpour, Gellert, Asefzadeh, Updegraff, Molloy and Sniehotta2014) demonstrates unidimensionality and high levels of internal consistency (Cronbach's α = 0.84).

Plasma level of mood stabilizer

The primary outcome of MA was also assessed using objective indices. Specifically, plasma levels of mood stabilizers were obtained from biochemistry laboratories at each center, and levels of three mood stabilizers were assayed: Lithium, Carbamazepine, and Sodium valproate.

Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire – Specific (BMQ-specific)

The BMQ-specific (Horne et al. Reference Horne, Weinman and Hankins1999) was used to assess beliefs about medications prescribed for personal use and has been shown to be correlated to adherence (Pakpour et al. Reference Pakpour, Gholami, Esmaeili, Naghibi, Updegraff, Molloy and Dombrowski2015). The measure reflects two domains (necessity and concerns) and each domain is assessed using five items that patients are asked to indicate their agreement with on a 5-point Likert scale (from 1: strongly disagree to 5: strongly agree). The necessity domain assesses patients’ beliefs about the necessity of the medication (e.g. Without my medicines I would be very ill), while the concerns domain examines patients’ beliefs about the possible adverse effects of the medication (e.g. Having to take medicines worries me). Scores can range between 5 and 25, with higher scores indicating stronger beliefs about the necessity of the medication or a higher level of concern about taking the medicine, respectively. The Persian version of the BMQ has promising psychometric properties and has been used to assess beliefs about medications among an Iranian sample with diabetes (Aflakseir, Reference Aflakseir2012).

Intention

Patients’ intention to take their medication was measured using a questionnaire adapted from Pakpour et al. (Reference Pakpour, Gellert, Asefzadeh, Updegraff, Molloy and Sniehotta2014). Patients were asked to indicate their agreement with five statements (e.g. I intend to take regular medication in the future) on a 5-point Likert scale (1: completely disagree to 5: completely agree). Internal consistency of the scale was adequate (Cronbach's α = 0.91).

Self-monitoring

Self-monitoring was measured by three items (e.g. During the last week, I have consistently monitored when to take my medications, on a 5-point Likert scale from not at all true (1) to exactly true (5) (Pakpour et al. Reference Pakpour, Gholami, Esmaeili, Naghibi, Updegraff, Molloy and Dombrowski2015). Cronbach's α for the scale was 0.89.

Self-report Behavioral Automaticity Index (SRBAI)

The SRBAI comprises four items from Self-Report Habit Index (Gardner et al. Reference Gardner, Abraham, Lally and de Bruijn2012), that measure the extent to which relevant behaviors are performed automatically (a key component of habit; Orbell & Verplanken, Reference Orbell and Verplanken2010). Each item starts with the stem Behavior X is something…and is followed by (1) I do automatically; (2) I do without having to consciously remember; (3) I do without thinking; and (4) I start doing before I realize I am doing it (Gardner et al. Reference Gardner, Abraham, Lally and de Bruijn2012). All items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1: disagree to 5: agree).

Action and coping planning

Action planning was measured using four items: I have made a detailed plan regarding when / where / how often / how to take medication. Similarly, coping planning was measured using four items: I have made a detailed plan regarding… (1) what to do if something interferes; (2) what to do if I forget to take my medication; (3) how to motivate myself if I don't feel like taking my medication; and (4) how to prevent myself from being distracted. All items measuring action planning and coping planning were rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1: completely disagree to 5: completely agree) and showed high levels of internal consistency in the present research (Cronbach's α = 0.90).

Perceived behavioral control (PBC)

PBC was measured using four items on a 5-point Likert scale (1: completely disagree to 5: completely agree) that have proved internally consistent in the present research (Cronbach's α = 0.94). Sample items include: For me to take regular medication in the future is… and It is up to me to take regular medication…

Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS)

The YMRS contains 11 items each describing a specific mania syndrome. Clinicians were asked to rate how severely the patients have experienced each syndrome within the past 2 days. The items include elevated mood, increased motor and activity-energy, sexual interest, sleep, irritability, speech rate and amount, language/thought disorder, thought content, disruptive/aggressive behavior, appearance, and insight. All items were rated from 0 (absent) to 4 (the highest level), and four of the items (irritability, speech, thought content, and disruptive/aggressive behavior) were double-weighted (Young et al. Reference Young, Biggs, Ziegler and Meyer1978; McIntyre et al. Reference McIntyre, Mancini, Srinivasan, McCann, Konarski and Kennedy2004) when computing the overall score.

Montgomery Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS)

The MADRS contains 10 items designed to measure indicators of depression (e.g. reduced appetite). The MADRS is designed to be particularly sensitive to the effects of treatment (such as antidepressants) among people with mood disorders. Clinicians were asked to respond to each of the items on a 7-point Likert scale and total scores could range from 0 (no symptoms of depression) to 60 (highest level of depression (Montgomery & Asberg, Reference Montgomery and Asberg1979).

Clinical Global Impressions-Bipolar-Severity of Illness (CGI-BP-S)

The CGI-BP-S is modified from Clinical Global Impressions Scale for specific use with patients with BD. The CGI-BP-S comprised three measures to which clinicians were asked to respond using a 7-point Likert scale. The measures evaluated: (1) The severity of illness (Considering your total clinical experience with this particular population, how mentally ill is the patient at this time?); (2) change from preceding phase (Compared to the phase immediately preceding this trial, how much has the patient changed?); (3) change from worst phase (Compared to the patient's worst phase of illness prior to the current medication trial or during the early titration phase, how much has the patients changed?). A lower score on the CGI-BP-S suggests a better condition (Spearing et al. Reference Spearing, Post, Leverich, Brandt and Nolen1997)

Quality of Life in Bipolar Disorder scale (QoL.BD)

The QoL.BD contains 12 items and is designed to capture patients’ subjective perceptions of BD-specific QoL. Each item asks about a specific experience in the past week (e.g. Felt physically well). Patients are asked to respond on a 5-point Likert scale (1: strongly agree to 5: strongly disagree), and a higher score represents a higher level of QoL (Michalak et al. Reference Michalak and Murray2010).

Adverse drug reaction (ADR)

Adverse reactions to the prescribed medications were assessed using a questionnaire adapted from the clinical monitoring form for mood disorders (Sachs et al. Reference Sachs, Guille and McMurrich2002). Patients were asked to indicate the severity of nine side effects (e.g. tremor, dry mouth, etc.) on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from none (0) to severe (4). A total score was computed as the sum of the severity of each side effect and could range from 0 to 36 with higher scores indicating more severe side effects.

Randomization and masking

In order to prevent contamination between the EXP and UC groups, centers were used as unit of randomization rather than patients. Trained professionals at each center (e.g. physicians and nurses) enrolled participants. Centers were allocated in a 1:1 ratio to either the EXP or UC groups by a computer-generated list of random numbers. Five clusters were assigned to the EXP group and five clusters to the UC group. Figure 1 illustrates the allocation to condition and the flow of participants through the trial.

Across centers, 538 patients were referred to the trial: 43 declined to be screened for eligibility, 217 did not meet screening criteria, and we lost contact with eight. A total of 270 patients underwent baseline assessment and 134 were randomized to the UC group and 136 to the EXP group. As a result, each center recruited an average of 26 patients. Assessors, psychologists, and psychiatrists were blind to the intervention status of the participants.

Sample size

The required sample size was calculated based on the primary outcome measure (the MARS). It was estimated that 132 patients would be needed in each condition to detect an effect size of 1 point in the MARS, with 85% power and a significance level of 5%, assuming an intracluster correlation coefficient of 0.05, a mean cluster size equal to 27, and that 10% of the patients would likely be lost to follow up.

Statistical analysis

Due to the hierarchical nature of the data (i.e. patients were nested within centers), we used multilevel linear mixed modeling to investigate the efficacy of the intervention. Three levels of analysis – time, patients, and centers – were estimated with a restricted iterative generalized least square (RIGLS) estimation. Therefore, for each model, three fixed effects were entered; an intercept term, Time and condition (the UC group served as the reference group).

To decompose the interaction between condition and time, we compared the effects of condition at each time point (i.e. 1 and 6 months after treatment) on each dependent variable. The Benjamini and Hochberg false discovery rate was used to adjust p values for multiple comparisons. In addition, Krull and MacKinnon's three-step recommendations for conducting mediation analyses were performed to identify potential mediators of treatment effects (Krull & MacKinnon, Reference Krull and MacKinnon1999). All tests were two sided with a significance level of <0.05 and analyses were performed on an intent-to-treat basis using MLwiN 2.27 software.

Results

Randomization check

Table 1 summarizes the baseline and clinical characteristics of the two groups. About 51% of the participants in the UC group and 55% of the participants in the EXP group were females and the mean age of the patients was 41.2 (6.4) years in the UC group and 41.8 (8.4) in the EXP group. The mean age of onset of BD was 24 years for both groups.

Table 1. Baseline and clinical characteristics of patients by condition

Note. s.d., standard deviation.

Effects of the intervention on the primary outcome: medication adherence

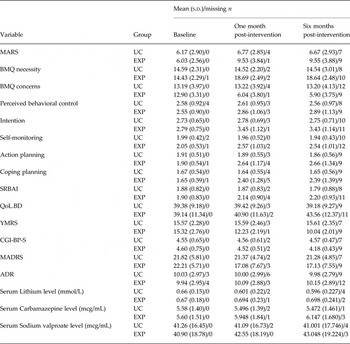

Table 2 provides the descriptive statistics for all outcome measures by condition and time. Tables 3 and 4 show the findings of three-level multiple linear regression models examining the effect of the intervention on outcomes. MA improved over time in both the EXP and UC groups. However, scores on the MARS indicated a greater improvement in MA among patients in the EXP group: M baseline = 6.03 (s.d. = 2.56) and M six months = 9.55 (s.d. = 3.88); than among patients in the UC group: M baseline = 6.17 (s.d. = 2.90) and M six months = 6.67 (s.d. = 2.93). In support of this idea, after taking into account the study center and repeated measurement over time, our multilevel mixed models showed that patients in the EXP group had significantly higher MARS scores than did patients in the UC group both one (B = 3.15; p < 0.001) and 6 months (B = 3.20; p < 0.001) after the intervention (Table 3).

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for all outcome measures by condition and time

Note. s.d., standard deviation; UC, usual care group; EXP, experimental group; BMQ, Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire; SRBAI, Self-report Behavioral Automaticity Index; MARS, Medication Adherence Rating Scale; QoL.BD, Quality of Life in Bipolar Disorder scale; YMRS, Young Mania Rating Scale; CGI-BP-S, Clinical Global Impressions-Bipolar-Severity of Illness; MADRS, Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale; ADR, Adverse drug reaction or adverse drug effect.

Table 3. Three-level multiple linear regression models predicting medication adherence, intention, perceived behavioral control, automaticity of medication taking, self-monitoring, action, and coping planning

Note. UC, usual care group; EXP, experimental group; MARS, Medication Adherence Rating Scale; INT, intention; PBC, Perceived behavioral control; SRBAI, Self-report Behavioral Automaticity Index; SM, Self-monitoring; ACP, Action planning; CP, Coping planning; ADR, Adverse drug reaction.

Table 4. Three-level multiple linear regression models predicting beliefs about medication, Mania symptoms, severity of illness, depression, and quality of life

Note. UC, usual care group; EXP, experimental group; BMQ, Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire; YMRS, Young Mania Rating Scale; CGI-BP-S, Clinical Global Impressions-Bipolar-Severity of Illness; MARDS, Montgomery Åsberg Depression Rating Scale; QoL.BD, Quality of Life in Bipolar Disorder scale; ADR, Adverse drug reaction.

Analysis of the objective measures of MA; namely, plasma level of mood stabilizers, indicated that patients in the UC group had slightly decreased levels of Lithium (baseline: 0.660 mmol/L; 6 month: 0.596 mmol/L), Carbamazepine (baseline: 5.580 mcg/mL; 6 month: 5.472 mcg/mL), and Sodium valproate (baseline: 41.255 mcg/mL, 6 month: 41.001 mcg/mL) at 6 months post-intervention, suggesting that they may not have been adhering to their medication regimen. In contrast, patients in the EXP group had increased levels of Lithium (baseline: 0.665 mmol/L; 6 month: 0.698 mmol/L), Carbamazepine (baseline: 5.596 mcg/mL; 6 month: 6.147 mcg/mL), and Sodium valproate (baseline: 40.094 mcg/mL; 6 month: 43.048 mcg/mL), supporting the beneficial effects of the intervention on MA suggested by the self-report measure of adherence. After controlling for study center and repeated measurement, patients in the EXP group had significantly higher plasma levels of mood stabilizers than did patients in the UC group at 1 month (B = 0.108 for Lithium, 1.53 for Carbamazepine, and 3.62 for Sodium valproate; p < 0.001), and 6 months (B = 0.178 for Lithium, 1.40 for Carbamazepine, and 5.28 for Sodium valproate; p < 0.001) post-intervention (see online Supplementary Table S2).

Effects of the intervention on secondary outcomes

Almost all secondary outcomes improved over time in the EXP group (see Table 2), and the findings of multiple linear regression models (reported in Tables 3 and 4) show that patients in the EXP group had significantly better outcomes on all secondary measures 1 month and 6 months after the intervention, compared with patients in the UC group, except for the measure of QoL at 1 month follow-up. Therefore, patients in the EXP group had stronger intentions to take their medication, believe that they had more control over so doing, that taking their medication was more automatic, and were more likely to form action and coping plans to promote MA.

There was also evidence of a decrease in clinical symptoms among patients in the EXP group, relative to patients in the UC group, as shown by significant effects of group on the YMRS (B = −5.32; p < 0.001), CGI-BP-S (B = −0.528; p < 0.001), and MARDS (B = −4.54; p < 0.001). Furthermore, the QoL of patients in the EXP group improved significantly more than among patients in the UC group (B = 1.17; p = 0.025).

Mediation analyses

Online Supplementary Table S3 in the online Supplementary Materials shows the direct and mediated effects of group on MA and QoL. The effect of the intervention on self-reported MA were mediated by changes in beliefs about medication (i.e. beliefs about the necessity of taking the medication and concern about the possible adverse effects of the medication), intention, self-monitoring, action planning, and coping planning. In turn, MA mediated the effect of the intervention on QoL.

We also examined whether self-reported MA (i.e. scores on the MARS) mediated the effect of the intervention on plasma levels of mood stabilizers. The results of the mediation analysis indicated that self-reported MA mediated the effect of the intervention on improvements in plasma levels of mood stabilizers. Specifically, scores on the MARS mediated the effect of the intervention effect on improvements in Serum Lithium levels at 1 month (B = 0.32; s.e. = 0.10; p < 0.001) and 6 month (B = 0.42; s.e. = 0.07; p < 0.001) follow-ups, improvements in Serum Carbamazepine levels at 1 month (B = 2.46; s.e. = 0.36; p < 0.001) and 6 month (B = 2.59; s.e. = 0.49; p < 0.001) follow-ups, and on improvements in Serum Sodium Valproate levels at 1 month (B = 2.17; s.e. = 0.68; p < 0.001) and 6 month (B = 1.92; s.e. = 0.62; p < 0.001) follow-ups.

Discussion

The aim of the present research was to assess the efficacy of a multifaceted intervention on MA and health outcomes in patients with BD. We found that a combination of brief sessions of MI, together with psychoeducation and efforts to engage family members in promoting adherence led to significant improvements in objective and self-report measures of MA, as well as in various clinical and functional outcomes compared with usual care. As such, we hope that the findings are informative to mental health clinicians seeking to promote MA among patients with BD and provide a rationale for designing and implementing multifaceted interventions to improve MA in such patients.

A few prior studies have investigated whether interventions based on MI can improve MA in patients with BD. In a quasi-experimental pilot study of 21 elderly subjects with BD, Depp et al. showed that a multifaceted intervention, including motivational training improved MA, as well as depressive symptoms and QoL (Depp et al. Reference Depp, Lebowitz, Patterson, Lacro and Jeste2007). However, this was only a preliminary pilot study with a simple training intervention and a limited outcome measure. Another study on patients with BD in Iran, showed the effectiveness of an intervention based on psychoeducation. This study included an 18 month follow-up and measured QoL, medication compliance as well as frequency of hospitalization showing considerable improvements in each outcome (Javadpour et al. Reference Javadpour, Hedayati, Dehbozorgi and Azizi2013). However, the study only involved one center with 108 patients the intervention only used psychoeducation and did not include family members.

In addition to MI, our intervention included other components, namely psychoeducation and engagement of a family member. We found promising effects of the intervention on both self-reported and objective measures of MA. Furthermore, our findings also pointed to improvements in symptoms and QoL, which mediation analyses indicated can be attributed to improved MA.

Strengths and limitations

The present research had several strengths. First, we used both self-report and objective outcome measures to ensure the validity of our findings. Second, using multiple outcome measures targeting different domains allowed us to look at the effect of the intervention on different aspects of health and functioning. Third, we used a multilevel linear mixed model to evaluate the effect of intervention on outcomes.

Our findings should be interpreted in light of some limitations, however. First, family engagement constituted an important component of the intervention in the present research. While we deem this to be a strength of our multifaceted approach, we acknowledge that family likely plays a more significant role in individuals who live in Middle Eastern cultures than in other, more Western societies (Daneshpour, Reference Daneshpour1998). Therefore, the effect of the family component of our intervention might not necessarily be generalizable to other cultures. Second, we did not assess the effect of our intervention beyond 6 months of follow-up. However, a meta-analysis by MacDonald and colleagues showed that the effects of interventions on MA seemed to be durable for up to 2 years (MacDonald et al. Reference MacDonald, Chapman, Syrett, Bowskill and Horne2016). There is no reason to believe that the effects of the present intervention might not also be maintained over this period. Third, it might be argued that a longer intervention might improve adherence rates even further. However, the feasibility of interventions should be considered in term of time and cost as well as efficacy as longer interventions may require greater investment of resources for a relatively small improvement in outcomes. Finally, a natural downside to a multifaceted approach to intervention is that it is difficult to isolate, which part of the intervention was most effective. Future research might usefully adopt factorial designs that systematically manipulate and compare different components of the intervention (e.g. the intervention with and without family support) in an effort to identify the active ingredients.

Conclusion

The present findings provide robust evidence that a multifaceted intervention based on MI, psychoeducation, and attempts to engage family members can improve MA among patients with BD. The implication is that healthcare professionals, especially those who deal with mental health aspects of people with psychiatric disorders such as BD, may use our findings to improve MA and adjust clinical symptoms in their clients.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329171700109X.

Declaration of Interest

None.