Introduction

Both bipolar disorder and borderline personality disorder (BPD) are significant public health problems. Both disorders are associated with impaired functioning (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Akiskal, Ames, Birnbaum, Greenberg, Hirschfeld and Wang2006; Morgan, Mitchell, & Jablensky, Reference Morgan, Mitchell and Jablensky2005; Skodol et al., Reference Skodol, Gunderson, McGlashan, Dyck, Stout, Bender and Oldham2002; Zanarini, Jacoby, Frankenburg, Reich, & Fitzmaurice, Reference Zanarini, Jacoby, Frankenburg, Reich and Fitzmaurice2009), increased use of health care services (Bender et al., Reference Bender, Dolan, Skodol, Sanislow, Dyck, McGlashan and Gunderson2001; Bryant-Comstock, Stender, & Devercelli, Reference Bryant-Comstock, Stender and Devercelli2002; Zanarini, Frankenburg, Hennen, & Silk, Reference Zanarini, Frankenburg, Hennen and Silk2004), increased rates of substance use disorders (Di Florio, Craddock, & van den Bree, Reference Di Florio, Craddock and van den Bree2014; Farren, Hill, & Weiss, Reference Farren, Hill and Weiss2012; Trull, Sher, Minks-Brown, Durbin, & Burr, Reference Trull, Sher, Minks-Brown, Durbin and Burr2000), and suicidality (Baldessarini, Pompili, & Tondo, Reference Baldessarini, Pompili and Tondo2006; Joyce, Light, Rowe, Cloninger, & Kennedy, Reference Joyce, Light, Rowe, Cloninger and Kennedy2010; Novick, Swartz, & Frank, Reference Novick, Swartz and Frank2010; Oldham, Reference Oldham2006; Pompili, Girardi, Ruberto, & Tatarelli, Reference Pompili, Girardi, Ruberto and Tatarelli2005). Patients with bipolar disorder or BPD most commonly present for the treatment of depression (Zimmerman, Chelminski, Dalrymple, & Rosenstein, Reference Zimmerman, Chelminski, Dalrymple and Rosenstein2017), therefore, it is not surprising that both disorders are frequently underdiagnosed (Ghaemi, Sachs, Chiou, Pandurangi, & Goodwin, Reference Ghaemi, Sachs, Chiou, Pandurangi and Goodwin1999; Zimmerman & Mattia, Reference Zimmerman and Mattia1999a, Reference Zimmerman and Mattia1999b). Calls for improved recognition have been voiced for both disorders (Dunner, Reference Dunner2003; Zimmerman, Reference Zimmerman2015).

For years there has been controversy as how to conceptualize the relationship between bipolar disorder and BPD. Some authors suggested that BPD is part of the bipolar spectrum (Agius, Lee, Gardner, & Wotherspoon, Reference Agius, Lee, Gardner and Wotherspoon2012; Akiskal, Reference Akiskal2004; Deltito et al., Reference Deltito, Martin, Riefkohl, Austria, Kissilenko, Corless and Morse2001; Perugi, Toni, Travierso, & Akiskal, Reference Perugi, Toni, Travierso and Akiskal2003). Several review articles summarized evidence in support of and opposition to the hypothesis that BPD belongs to the bipolar spectrum, with most of the recent reviews having concluded that BPD and bipolar disorder are valid and distinct diagnostic entities (Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Mulder, Outhred, Hamilton, Morris, Das and Malhi2017; Bayes, Parker, & Fletcher, Reference Bayes, Parker and Fletcher2014; Ghaemi, Dalley, Catania, & Barroilhet, Reference Ghaemi, Dalley, Catania and Barroilhet2014; Magill, Reference Magill2004; Paris, Reference Paris2004; Paris & Black, Reference Paris and Black2015; Paris, Gunderson, & Weinberg, Reference Paris, Gunderson and Weinberg2007; Parker, Reference Parker2014, Reference Parker2015; Smith, Muir, & Blackwood, Reference Smith, Muir and Blackwood2004). A growing body of research that directly compares patients with BPD and bipolar disorder has demonstrated that patients with the two disorders differ in clinical characteristics (Mneimne, Fleeson, Arnold, & Furr, Reference Mneimne, Fleeson, Arnold and Furr2018; Richard-Lepouriel et al., Reference Richard-Lepouriel, Kung, Hasler, Bellivier, Prada, Gard and Etain2019), frequency of suicide attempts (Bayes, Graham, Parker, & McCraw, Reference Bayes, Graham, Parker and McCraw2018; Perroud et al., Reference Perroud, Zewdie, Stenz, Adouan, Bavamian, Prada and Dayer2016; Richard-Lepouriel et al., Reference Richard-Lepouriel, Kung, Hasler, Bellivier, Prada, Gard and Etain2019), neurobiological substrates (Boen et al., Reference Boen, Hjornevik, Hummelen, Elvsashagen, Moberget, Holtedahl and Malt2019; Das, Calhoun, & Malhi, Reference Das, Calhoun and Malhi2014; Malhi et al., Reference Malhi, Tanious, Fritz, Coulston, Bargh, Phan and Das2013; Radaelli et al., Reference Radaelli, Poletti, Dallaspezia, Colombo, Smeraldi and Benedetti2012; Rossi et al., Reference Rossi, Lanfredi, Pievani, Boccardi, Beneduce, Rillosi and Frisoni2012), neuropsychological profiles (Feliu-Soler et al., Reference Feliu-Soler, Soler, Elices, Pascual, Perez, Martin-Blanco and Portella2013; Gvirts et al., Reference Gvirts, Braw, Harari, Lozin, Bloch, Fefer and Levkovitz2015), maladaptive self-schemas (Nilsson, Jorgensen, Straarup, & Licht, Reference Nilsson, Jorgensen, Straarup and Licht2010), temperament (Eich et al., Reference Eich, Gamma, Malti, Vogt Wehrli, Liebrenz, Seifritz and Modestin2014), and history of childhood abuse and neglect (Bayes et al., Reference Bayes, Graham, Parker and McCraw2018; Bayes et al., Reference Bayes, McClure, Fletcher, Roman Ruiz Del Moral, Hadzi-Pavlovic, Stevenson and Parker2016b; Fletcher, Parker, Bayes, Paterson, & McClure, Reference Fletcher, Parker, Bayes, Paterson and McClure2014; Mazer, Cleare, Young, & Juruena, Reference Mazer, Cleare, Young and Juruena2019; Perroud et al., Reference Perroud, Zewdie, Stenz, Adouan, Bavamian, Prada and Dayer2016; Richard-Lepouriel et al., Reference Richard-Lepouriel, Kung, Hasler, Bellivier, Prada, Gard and Etain2019).

The most frequently studied aspect of the interface between BPD and bipolar disorder has been the frequency of their co-occurrence. Several reviews of this literature have estimated a 20% overlap in diagnostic frequency. That is, approximately 20% of patients with bipolar disorder have comorbid BPD, and approximately 20% of patients with BPD have bipolar disorder (Fornaro et al., Reference Fornaro, Orsolini, Marini, De Berardis, Perna, Valchera and Stubbs2016; Frias, Baltasar, & Birmaher, Reference Frias, Baltasar and Birmaher2016; Zimmerman & Morgan, Reference Zimmerman and Morgan2013). Thus, there is a meaningful number of patients who are diagnosed with both disorders though the majority of patients diagnosed with one disorder are not diagnosed with the other.

It has been frequently noted that distinguishing BPD from bipolar disorder is challenging and difficult (Bayes et al., Reference Bayes, Parker and Fletcher2014; Bayes & Parker, Reference Bayes and Parker2016; Coulston, Tanious, Mulder, Porter, & Malhi, Reference Coulston, Tanious, Mulder, Porter and Malhi2012; Ghaemi et al., Reference Ghaemi, Dalley, Catania and Barroilhet2014; McDermid & McDermid, Reference McDermid and McDermid2016; Parker, Reference Parker2014). Consequently, reviews and commentaries have focused attention on differential diagnosis and identifying clinical features to distinguish the two (Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Mulder, Outhred, Hamilton, Morris, Das and Malhi2017; Bayes et al., Reference Bayes, Parker and Fletcher2014; Ghaemi et al., Reference Ghaemi, Dalley, Catania and Barroilhet2014). However, the emphasis on distinguishing between the two disorders suggests that this is an either/or state of affairs. Focusing on differential diagnosis might discourage clinicians from making both diagnoses in a patient, when appropriate, and could result in overlooking an important comorbidity in patients with the greatest need.

While there is a burgeoning literature comparing patients with BPD and bipolar disorder, much less research has characterized patients with both disorders (Parker, Bayes, McClure, Del Moral, & Stevenson, Reference Parker, Bayes, McClure, Del Moral and Stevenson2016). Frias et al. (Reference Frias, Baltasar and Birmaher2016) recently reviewed the literature on the clinical impact of one disorder on the other. Frias et al. (Reference Frias, Baltasar and Birmaher2016) found that among patients with bipolar disorder those with comorbid BPD reported more mood episodes, an earlier age of onset of bipolar disorder, greater suicidality, greater hostility, and a higher prevalence of substance abuse. Little or no data existed on differences in treatment response, functioning, time unemployed, receiving disability payments, or prospectively observed longitudinal course. Likewise, little research has compared patients with BPD who do and do not have bipolar disorder.

It has been our clinical experience that patients with both bipolar disorder and BPD are a group at high risk for suicide, marked impairment, and are high utilizers of care. In the current report from the Rhode Island Methods to Improve Diagnostic Assessment and Services (MIDAS) project, we compare psychiatric outpatients with BPD and bipolar disorder to patients with BPD without bipolar disorder and patients with bipolar disorder without BPD. We hypothesized that the patients with BPD/bipolar disorder would exhibit significantly more psychosocial morbidity than patients with only one of these disorders.

Method

The Rhode Island MIDAS project represents an integration of research methodology into a community-based outpatient practice affiliated with an academic medical center and has been described previously (Zimmerman, Reference Zimmerman and First2003). The Rhode Island Hospital institutional review committee approved the research protocol, and all patients provided informed, written consent.

The sample examined in the current report is derived from the 3800 psychiatric outpatients evaluated with semi-structured diagnostic interviews, 59 of whom were diagnosed with current bipolar I (n = 26) or bipolar II (n = 33) disorder with BPD, 128 with bipolar disorder I (n = 50) or bipolar II (n = 78) disorder without BPD, and 330 with BPD without bipolar disorder. We excluded patients with bipolar disorder not otherwise specified and bipolar disorder in partial or full remission.

Patients were interviewed by a diagnostic rater who administered a modified version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, Reference First, Spitzer, Gibbon and Williams1995) supplemented with questions from the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (SADS) (Endicott & Spitzer, Reference Endicott and Spitzer1978) and the BPD section of the Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality (SIDP-IV) (Pfohl, Blum, & Zimmerman, Reference Pfohl, Blum and Zimmerman1997). The assessment of all DSM-IV personality disorders was not introduced until the study was well underway and the procedural details of incorporating research interviews into our clinical practice had been well established, though we had introduced the assessment of borderline and antisocial personality disorder near the beginning of the study. In the middle of the study we stopped administering the full SIDP-IV and continued to only administer the BPD module. The assessment of personality disorders always followed the assessment of Axis I disorders. Information on BPD was missing for four patients with bipolar II disorder, and these patients were excluded from the analysis.

The interview included items from the SADS (Endicott & Spitzer, Reference Endicott and Spitzer1978) assessing episode duration, symptom severity, suicidal ideation, psychosocial functioning, and lifetime history of suicide attempts and psychiatric hospitalizations. One item assessed the amount of time missed from work due to psychiatric reasons during the past 5 years. Consistent with a prior report, we defined persistent unemployment as not working due to psychiatric illness for at least 2 years in the past 5 years, and chronic unemployment as working none, or practically none, of the time because of reasons related to psychopathology during the past 5 years (Zimmerman et al., Reference Zimmerman, Galione, Chelminski, Young, Dalrymple and Ruggero2010). Patients who did not work at all because they were not expected to work (e.g. retired, student, housewife, physically ill, or some other reason not related to psychopathology) were excluded from this analysis. Approximately midway through the project we began to inquire whether patients had received disability payments due to psychiatric illness during the 5 years prior to the evaluation. The questions about time missed from work and disability were included at the beginning of the interview, preceding the inquiry about the presence of specific disorders.

Following the SCID interview patients completed a booklet of questionnaires that included the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (Bernstein et al., Reference Bernstein, Fink, Handelsman, Foote, Lovejoy, Wenzel and Ruggiero1994). We compared the groups on the five subscales of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire – emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, physical neglect, and emotional neglect.

The clinical global index of depression severity (Guy, Reference Guy1976) and global assessment of functioning (GAF) were rated by the interviewers on all patients. Family history diagnoses were based on information provided by the patient. The interview followed the guide provided in the Family History Research Diagnostic Criteria (FH-RDC) (Endicott, Andreasen, & Spitzer, Reference Endicott, Andreasen and Spitzer1978) and assessed the presence or absence of problems with anxiety, mood, substance use, and other psychiatric disorders for all first-degree family members. Morbid risks were calculated using age-corrected denominators or bezugsiffers based on Weinberg's shorter method (Stromgren, Reference Stromgren1950). Thus, relatives over the age of risk for the particular illness were given a value of 1; those within the age for risk were given a value of 0.5, and those below it were given a value of 0. These ages of risk were based on the distribution of ages of onset in our probands (Zimmerman & Chelminski, Reference Zimmerman and Chelminski2003b). Morbid risks were compared using the χ2 statistic.

The diagnostic raters were highly trained and monitored throughout the project to minimize rater drift as has been described in prior reports from the MIDAS project. Reliability was examined in 65 patients using an observer-rater design. Of relevance to the current report, the reliabilities for diagnosing bipolar disorder (k = 0.75) and BPD (k = 1.0) were good.

Data analysis

We compared three nonoverlapping groups of patients: bipolar/BPD, bipolar disorder without BPD (bipolar disorder), and BPD without bipolar disorder (BPD). We focused on two 2-group comparisons: bipolar/BPD v. bipolar and bipolar/BPD v. BPD because we had previously compared patients with bipolar disorder and BPD (Zimmerman et al., Reference Zimmerman, Ellison, Morgan, Young, Chelminski and Dalrymple2015). The t tests were used to compare the groups on continuously distributed variables. Categorical variables were compared by the χ2 statistic, or by Fisher's exact test if the expected value in any cell of a 2 × 2 table was less than 5.

Hedge's g was calculated for effect size estimates of all t tests. Hedge's g was preferred to the more common Cohen's d because the comparison groups were dissimilar in size. Hedge's g accounts for unequal sample sizes by weighing each group's standard deviation by its sample size and pooling the weighted standard deviations for the divisor. The Phi coefficient was calculated for effect size estimates of all 2 × 2 χ2 comparisons, and Cramer's V was determined for all other χ2 comparisons involving a variable with more than two levels. Confidence intervals were generated for all t tests.

Results

The 517 patients included 164 (31.7%) men and 353 (68.3%) women who ranged in age from 18 to 74 years (mean = 33.8, s.d. = 11.1). About two-fifths of the subjects were single (43.1%, n = 223); the remainder were married (26.6%, n = 138), divorced (14.9%, n = 77), living with someone as if in a marital relationship (8.9%, n = 46), separated (5.8%, n = 30), or widowed (0.6%, n = 3). Approximately three-quarters of the patients graduated high school (72.0%, n = 372), though only a minority graduated a 4-year college (19.1%, n = 99). The racial composition of the sample was 88.6% (n = 458) white, 5.6% (n = 29) black, 2.9% (n = 15) Hispanic, 1.0% (n = 5) Asian, and 1.9% (n = 10) from another or a combination of the above racial backgrounds. The data in Table 1 shows there are no significant differences in demographic characteristics between the patients with bipolar/BPD and the two comparison groups other than the patients with bipolar/BPD being younger than the patients with bipolar disorder. Consistent with the difference in ages, the bipolar/BPD patients also had an earlier age of onset of bipolar disorder compared to the patients with bipolar disorder (13.2 ± 6.9 v. 19.0 ± 11.2, t = 4.30, p < 0.001, g = 0.57).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of psychiatric outpatients with borderline personality disorder and bipolar disorder (bipolar/BPD), patients with borderline personality without bipolar disorder (BPD) and patients with bipolar disorder without borderline personality disorder

a Phi coefficient is reported for 2 × 2 comparisons, Cramer's V is reported for all others.

Comorbidity was more frequent in the bipolar/BPD patients (Table 2). Compared to patients with bipolar disorder, significantly more bipolar/BPD patients were diagnosed with three or more current Axis I disorders. Compared to the patients with bipolar disorder, the bipolar/BPD patients reported significantly more posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), obsessive-compulsive disorder, drug use disorder, and somatoform disorder. Compared to the patients with BPD, the patients with bipolar/BPD reported significantly more PTSD and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Table 2. Frequency of current DSM-IV Axis I disorders in psychiatric outpatients with borderline personality disorder and bipolar disorder (bipolar/BPD), patients with borderline personality without bipolar disorder (BPD) and patients with bipolar disorder without borderline personality disorder

a Not counting bipolar disorder.

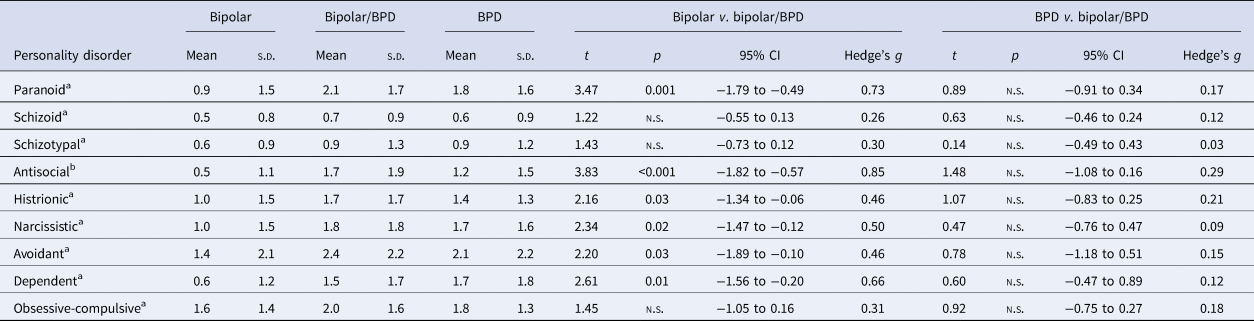

Bipolar/BPD patients were significantly more often diagnosed with a personality disorder (other than BPD) than the patients with bipolar disorder (59.4% v. 37.0%, χ2 = 4.66, p < 0.05, Phi = 0.16). There was no difference in the frequency of a personality disorder between patients with bipolar/BPD and BPD (59.4% v. 52.0%, χ2 = 0.60, n.s., Phi = 0.04). Too few patients were diagnosed with specific personality disorders; therefore, we examined personality disorder dimensional scores (Table 3). We computed a dimensional score for each DSM-IV personality disorder based on the number of criteria that were present. Compared to the patients with bipolar disorder, the patients with bipolar/BPD reported significantly more paranoid, antisocial, histrionic, narcissistic, avoidant, and dependent features. There were no differences between the bipolar/BPD and BPD patients.

Table 3. DSM-IV personality disorder dimensional scores in psychiatric outpatients with borderline personality disorder and bipolar disorder (bipolar/BPD), patients with borderline personality without bipolar disorder (BPD) and patients with bipolar disorder without borderline personality disorder

a Bipolar (n = 80–81), bipolar/BPD (n = 31–32), and BPD (n = 173–175).

b Bipolar (n = 96), bipolar/BPD (n = 44), and BPD (n = 231).

The bipolar/BPD patients had the most psychopathology in their first-degree relatives (Table 4). Compared to patients with bipolar disorder, the morbid risk for depression, bipolar disorder, PTSD, specific phobia and drug and alcohol use disorders was significantly higher in the bipolar/BPD patients. Compared to the patients with BPD, the bipolar/BPD patients had significantly higher morbid risks for bipolar disorder, PTSD and drug and alcohol use disorder.

Table 4. Morbid risks for psychiatric disorders in first-degree relatives of psychiatric outpatients with psychiatric outpatients with borderline personality disorder and bipolar disorder (bipolar/BPD), patients with borderline personality without bipolar disorder (BPD) and patients with bipolar disorder without borderline personality disorder

Psychosocial morbidity was greatest in the bipolar/BPD patients (Tables 5 and 6). Compared to patients with bipolar disorder, the bipolar/BPD patients reported more episodes of depression, more anger, suicidal ideation, history of suicide attempts, childhood trauma, chronic and persistent unemployment, impaired social functioning, psychiatric hospitalizations, and were more likely to receive disability payments. The bipolar/BPD patients received significantly lower ratings on the GAF than the patients with bipolar disorder, and they were significantly more likely to be rated 50 or lower on the GAF. The bipolar/BPD patients also exhibited significantly more psychosocial morbidity than the patients with BPD, though the differences between the groups were not as robust. The bipolar/BPD patients reported more episodes of depression, childhood trauma, chronic and persistent unemployment, history of suicide attempts, and psychiatric hospitalizations.

Table 5. Clinical characteristics psychiatric outpatients with borderline personality disorder and bipolar disorder (bipolar/BPD), patients with borderline personality without bipolar disorder (BPD) and patients with bipolar disorder without borderline personality disorder

a Ratings based on the SADS.

b Bipolar (n = 80), bipolar/BPD (n = 33), and BPD (n = 206).

Table 6. Psychosocial morbidity in psychiatric outpatients with borderline personality disorder and bipolar disorder (bipolar/BPD), patients with borderline personality without bipolar disorder (BPD) and patients with bipolar disorder without borderline personality disorder

a Ratings from Schedule of Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia.

b Higher value indicates poorer social functioning.

Discussion

The distinction between BPD and bipolar disorder is important because the two disorders suggest different treatment emphases – a focus on pharmacotherapy with possible adjunctive psychotherapy for patients with bipolar disorder v. a focus on psychotherapy with possible adjunctive medication for patients with BPD (Ghaemi et al., Reference Ghaemi, Dalley, Catania and Barroilhet2014; Paris, Reference Paris2018; Paris & Black, Reference Paris and Black2015). Because of the treatment implications, much has been written about the importance of making the differential diagnosis, and several experts have identified nondiagnostic factors that could be used to assist in arriving at the correct diagnosis (Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Mulder, Outhred, Hamilton, Morris, Das and Malhi2017; Bayes et al., Reference Bayes, Parker and Fletcher2014; Ghaemi et al., Reference Ghaemi, Dalley, Catania and Barroilhet2014; Paris & Black, Reference Paris and Black2015). However, the evaluation of patients for possible bipolar disorder or BPD should not be viewed as a dichotomous either/or decision because a number of patients have both disorders (Parker et al., Reference Parker, Bayes, McClure, Del Moral and Stevenson2016).

Comorbid conditions, in general, are underrecognized (Miller, Dasher, Collins, Griffiths, & Brown, Reference Miller, Dasher, Collins, Griffiths and Brown2001; Shear et al., Reference Shear, Greeno, Kang, Ludewig, Frank, Swartz and Hanekamp2000; Zimmerman & Mattia, Reference Zimmerman and Mattia1999b). For example, although it is well recognized that anxiety disorders are common in patients with major depressive disorder (MDD), anxiety disorders are often overlooked in patients with a principal diagnosis of MDD (Zimmerman & Chelminski, Reference Zimmerman and Chelminski2003a). However, while the treatments for depression and anxiety disorders overlap, evidence-based treatments for bipolar disorder and BPD differ. Thus, while clinicians might seek diagnostic parsimony and diagnose only one disorder (Bayes & Parker, Reference Bayes and Parker2016; Parker, Reference Parker2015), in patients with bipolar disorder or BPD it is important for clinicians to not overlook the presence of the other disorder.

The results of the current study indicate that patients with both bipolar disorder and BPD are a group with severe psychosocial morbidity. Compared to patients with bipolar disorder, the bipolar/BPD patients had more comorbid disorders that cut across anxiety, substance use, somatoform, and personality disorders, more psychopathology in their first-degree relatives, more childhood trauma, more suicidality, more hospitalizations, poorer social functioning, more time unemployed, and were more likely to be receiving disability payments. While the differences between bipolar/BPD patients and patients with bipolar disorder were more robust than the differences between patients with bipolar/BPD and BPD, the added presence of bipolar disorder in patients with BPD was also associated with more PTSD in the patients as well as their family, more bipolar disorder and substance use disorders in the their first-degree relatives, more childhood trauma, more unemployment, more disability, more suicide attempts, and more hospitalizations.

Our results are consistent with prior studies which have found that bipolar/BPD patients, compared to patients with bipolar disorder without BPD, make more suicide attempts (Carpiniello, Lai, Pirarba, Sardu, & Pinna, Reference Carpiniello, Lai, Pirarba, Sardu and Pinna2011; Galfalvy et al., Reference Galfalvy, Oquendo, Carballo, Sher, Grunebaum, Burke and Mann2006; Joyce et al., Reference Joyce, Light, Rowe, Cloninger and Kennedy2010; Neves, Malloy-Diniz, & Correa, Reference Neves, Malloy-Diniz and Correa2009; Parker et al., Reference Parker, Bayes, McClure, Del Moral and Stevenson2016; Perugi et al., Reference Perugi, Angst, Azorin, Bowden, Vieta and Young2013; Richard-Lepouriel et al., Reference Richard-Lepouriel, Kung, Hasler, Bellivier, Prada, Gard and Etain2019; Zeng et al., Reference Zeng, Cohen, Tanis, Qizilbash, Lopatyuk, Yaseen and Galynker2015), are more frequently hospitalized (Neves et al., Reference Neves, Malloy-Diniz and Correa2009; Parker et al., Reference Parker, Bayes, McClure, Del Moral and Stevenson2016), have more comorbid anxiety and substance use disorders (McDermid et al., Reference McDermid, Sareen, El-Gabalawy, Pagura, Spiwak and Enns2015; Neves et al., Reference Neves, Malloy-Diniz and Correa2009; Perugi et al., Reference Perugi, Angst, Azorin, Bowden, Vieta and Young2013; Richard-Lepouriel et al., Reference Richard-Lepouriel, Kung, Hasler, Bellivier, Prada, Gard and Etain2019), lower ratings on the GAF (Carpiniello et al., Reference Carpiniello, Lai, Pirarba, Sardu and Pinna2011), greater childhood adversity (Goldberg & Garno, Reference Goldberg and Garno2009; McDermid et al., Reference McDermid, Sareen, El-Gabalawy, Pagura, Spiwak and Enns2015; Parker et al., Reference Parker, Bayes, McClure, Del Moral and Stevenson2016; Richard-Lepouriel et al., Reference Richard-Lepouriel, Kung, Hasler, Bellivier, Prada, Gard and Etain2019), and more mood disorder episodes (McDermid et al., Reference McDermid, Sareen, El-Gabalawy, Pagura, Spiwak and Enns2015; Neves et al., Reference Neves, Malloy-Diniz and Correa2009; Perugi et al., Reference Perugi, Angst, Azorin, Bowden, Vieta and Young2013).

Fewer studies have compared patients with BPD who have and have not been diagnosed with comorbid bipolar disorder. Parker and colleagues found that these two groups did not differ in childhood abuse, parental rearing style, suicide attempts or hospitalization, though bipolar/BPD patients had greater impairment in emotion regulation (Bayes, Parker & McClure, Reference Bayes, Parker and McClure2016a; Parker et al., Reference Parker, Bayes, McClure, Del Moral and Stevenson2016). Similarly, Richard-Lepouriel et al. (Reference Richard-Lepouriel, Kung, Hasler, Bellivier, Prada, Gard and Etain2019) reported that bipolar/BPD patients did not differ from patients with BPD in their history of suicide attempts, comorbid substance, anxiety or eating disorders, or number of mood disorder episodes. In the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study, the presence of bipolar disorder did not negatively impact the course of BPD over 4 years of prospectively observed follow-up (Gunderson et al., Reference Gunderson, Weinberg, Daversa, Kueppenbender, Zanarini, Shea and Dyck2006). Similar negative findings were found in a small study of inpatients with BPD treated on a unit specializing in the treatment of personality disorders (Goodman, Hull, Clarkin, & Yeomans, Reference Goodman, Hull, Clarkin and Yeomans1998).

While we found that the differences between bipolar/BPD patients and BPD were less robust than the differences between bipolar/BPD and bipolar patients, there were nonetheless several significant and meaningful differences between the two groups. What might account for the difference in the positive results of this study and negative results of other studies? We hypothesize that the methods of recruiting patients into the studies might have an influence. We evaluated patients upon presentation for treatment at a community-based, albeit hospital affiliated, outpatient clinical practice. Other studies recruited patients who were treated in programs specializing in the treatment of personality disorders or who had been referred to a study of BPD. Because of clinicians' reluctance to diagnose BPD (Zimmerman et al., Reference Zimmerman, McGonigal, Moon, Mehring, LaHaye, Berges and Schmidhofer2018), it is possible that primarily patients with more severe forms of BPD are diagnosed with BPD by their clinicians and thus referred to studies or treatment facilities focusing on BPD. The severity of BPD thus may have overshadowed the morbidity associated with bipolar disorder.

During the past decade significant effort has been put forth to improve the recognition of bipolar disorder in depressed patients. Several screening scales for bipolar disorder have been developed, and they have been extensively researched (Carvalho et al., Reference Carvalho, Takwoingi, Sales, Soczynska, Kohler, Freitas and Vieta2015). Several review articles and commentaries about the importance of recognizing bipolar disorder in patients presenting for the treatment of depression have been published in peer reviewed journals (Bowden, Reference Bowden2001; Hirschfeld & Vornik, Reference Hirschfeld and Vornik2004; Ketter, Reference Ketter2011; McIntyre, Reference McIntyre2014; Yatham, Reference Yatham2005). Much less has been written about the importance of improving the recognition of BPD (Zimmerman, Reference Zimmerman2016). Just as it is important for clinicians to include questions to screen for a history of manic or hypomanic episodes in their evaluation of depressed patients, it is important to screen for the presence of BPD in patients with mood disorders (Zimmerman, Balling, Dalrymple, & Chelminski, Reference Zimmerman, Balling, Dalrymple and Chelminski2019).

Most of the literature on bipolar disorder and BPD has focused on their differentiation. Because of some early papers suggesting that BPD belongs to the bipolar spectrum (Akiskal, Reference Akiskal2004; Angst et al., Reference Angst, Azorin, Bowden, Perugi, Vieta, Gamma and Young2011; Perugi et al., Reference Perugi, Toni, Travierso and Akiskal2003), a literature has emerged to test this hypothesis and numerous studies have directly compared patients with each diagnosis on demographic, clinical, life history, and biological variables, and indirectly compared them with regard to which treatments are most effective. While this literature has clearly demonstrated that these are distinct disorders, lost in the dialog is the importance of diagnosing both disorders when both are present. To date, limited research has examined what treatments might be helpful in patients with both diagnoses. There are only a small number of open-label trials of medication (Aguglia, Mineo, Rodolico, Signorelli, & Aguglia, Reference Aguglia, Mineo, Rodolico, Signorelli and Aguglia2018; Preston, Marchant, Reimherr, Strong, & Hedges, Reference Preston, Marchant, Reimherr, Strong and Hedges2004), one controlled medication trial (Frankenburg & Zanarini, Reference Frankenburg and Zanarini2002), and no controlled psychotherapy trials of patients with both disorders (Riemann et al., Reference Riemann, Weisscher, Goossens, Draijer, Apenhorst-Hol and Kupka2014).

We have noted elsewhere that the variables used to validate the bipolar spectrum overlap with the variables used to validate BPD (Galione & Zimmerman, Reference Galione and Zimmerman2010). There are relatively few disorder specific validators. We previously proposed five disorder specific validators: type of affective lability, temperament, childhood trauma history, comorbid PTSD, and family history of bipolar disorder. Prior studies have found that compared to patients with bipolar disorder, patients with BPD experience more affective lability characterized by irritability (Henry et al., Reference Henry, Mitropoulou, New, Koenigsberg, Silverman and Siever2001; Nilsson et al., Reference Nilsson, Jorgensen, Straarup and Licht2010; Reich, Zanarini, & Fitzmaurice, Reference Reich, Zanarini and Fitzmaurice2012; Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Stanley, Oquendo, Goldberg, Zalsman and Mann2007). While we did not include a measure of affective switches in the current study, we found that during the week before the evaluation the bipolar/BPD patients reported higher levels of subjective and overtly expressed anger. We did not include a measure of temperament, though we found that the patients with bipolar/BPD differed from patients with bipolar disorder on most DSM-IV personality disorder dimensions. We found that compared to patients with bipolar disorder only and BPD only, PTSD was significantly more often diagnosed in the bipolar/BPD patients. Likewise, childhood abuse and neglect were significantly greater in the bipolar/BPD patients than in patients with bipolar disorder or BPD. A family history of bipolar disorder was also greater in the first-degree family members of the bipolar/BPD probands than the bipolar and BPD probands. Thus, the diagnostic specific indicators of both BPD and bipolar distinguished the bipolar/BPD patients from patients with either diagnosis alone. This would argue against suggestions that bipolar/BPD is simply a more severe variant of either bipolar disorder or BPD.

In the current study we used the DSM-IV definition of bipolar II disorder which requires a minimum duration of 4 days to diagnose a hypomanic episode. Some researchers advocate a broader definition of bipolar disorder that requires only a 1- or 2-day duration to define hypomania (Angst et al., Reference Angst, Gamma, Benazzi, Ajdacic, Eich and Rossler2003; Benazzi, Reference Benazzi2007). The breadth of the DSM-IV definition will impact the prevalence of bipolar disorder and bipolar/BPD. We decided a priori not to include patients with bipolar disorder not otherwise specified because of the potential for greater diagnostic confusion and diagnostic error if a broader definition of bipolar II disorder was used. It is likely that the transient periods of affective instability characterized by anger and irritability that are typical of BPD would be more often misinterpreted as indicative of a hypomanic episode. Consequently, broadening the definition of bipolar II disorder would result in more false positive bipolar II diagnoses, and the diagnostic groups would not be as clearly distinguished.

A limitation of the study was that it was conducted in a single outpatient practice in which the majority of patients were white, female, and had health insurance. While the generalizability of any single-site study is limited, a strength of the study was that the patients were unselected with regard to meeting any inclusion or exclusion criteria. The MIDAS project includes patients with a variety of diagnoses and does not select cases that are prototypic, and thus more severe variants, of the diagnostic construct. Moreover, a strength of the study was the use of highly trained interviewers who diagnosed BPD and mood disorders with high reliability. Nonetheless, replication of the results in samples with different demographic characteristics is warranted. While the study was of psychiatric outpatients, approximately half of the patients had been previously hospitalized.

We focused on patients who were symptomatic at the time of the evaluation. This could have biased the sample toward individuals who were more chronically and persistently symptomatic. Semi-structured interviews such as the SIDP assess the features of personality disorders for recent time frames such as the past 2 years or the past 5 years, and thus do not identify personality disorders that have improved or resolved over time. In contrast, interviews such as the SCID assess a lifetime history of manic and depressive episodes. Had we included individuals whose bipolar disorder was in remission or partial remission, it would have biased the findings toward finding greater symptom severity and functional impairment in the patients with BPD compared to bipolar disorder. We therefore decided to focus on patients who met the criteria for either or both disorders at the time of presentation for their intake evaluation.

Current psychiatric state could have biased the assessment of some variables such as personality disorders. However, this bias should have been similar across diagnostic groups. We focused on patients who were presenting for treatment because if diagnosis predicts outcome and retention in treatment, it would have been more difficult to interpret findings based on symptom differences, level of psychosocial functioning, and personality variables if we included patients who were in ongoing treatment and in various stages of symptom remission. Moreover, there is research in support of the validity of personality disorder assessment in currently depressed patients (Morey et al., Reference Morey, Shea, Markowitz, Stout, Hopwood, Gunderson and Skodol2010). The assessment of episode duration and number of prior episodes were based on retrospective recall. A longitudinal prospective follow-up study with repeated assessments would better clarify the persistence of symptoms and syndromes in the groups.

We compared the groups on more than 60 variables, and because we made two 2-group comparisons, we conducted more than 120 statistical tests. Many of the group differences were predicted and this could justify a one-tailed test, but instead we used a more conservative two-tailed test and kept the p level at 0.05. With 120 comparisons six statistically significant group differences would be expected by chance and this would represent type-I error. However, we found 60 significant group differences thereby enhancing confidence that the group differences were not spurious.

Finally, we did not directly compare the patients with BPD and bipolar disorder as we have conducted this analysis previously and supported the validity of the distinction between these two diagnoses (Zimmerman et al., Reference Zimmerman, Ellison, Morgan, Young, Chelminski and Dalrymple2015).

In conclusion, the ongoing debate as to whether BPD does or does not belong to the bipolar spectrum, which has generated a robust empirical database establishing that these are distinct diagnostic entities, has sidetracked researchers and clinicians from recognizing the importance of diagnosing both disorders when both are present. Patients with both bipolar disorder and BPD represent a group with severe psychosocial morbidity who are often unemployed, suicidal, and utilize more costly forms of health care services. Efforts to identify effective approaches toward treating these patients have been minimal and are needed.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.