Introduction

The most common symptom in medicine is pain. More than half of complaints to physicians are reports of pain – commonly headache or back pain, on a chronic or acute basis. Up to 40% of the general population complains of chronic pain, with nearly 15% complaining of pain on a daily basis. Commonly, the basis for pain is not clearly identified (Marple et al. Reference Marple, Kroenke, Lucey, Wilder and Lucas1997).

The relationship between pain and depression is complex. Depression may be both a cause and a consequence of painful physical symptoms (PPS) (Axford et al. Reference Axford, Heron, Ross and Victor2008; Kroenke et al. Reference Kroenke, Shen, Oxman, Williams and Dietrich2008), with similar brain areas regulating both mood and the affective components of pain (Giesecke et al. Reference Giesecke, Gracely, Williams, Geisser, Petzke and Clauw2005). From 15% to 100% of patients complain of PPS at some point during an episode of major depressive disorder (MDD) (Bair et al. Reference Bair, Robinson, Katon and Kroenke2003). One large study of depressed patients concluded that, on average, 43.4% of patients had at least one pain complaint, with PPS present in 28.5% of patients with two and 61.9% of those with at least five depressive symptoms (Ohayon & Schatzberg, Reference Ohayon and Schatzberg2003).

The reported prevalence of pain complaints may be influenced in part by treatment setting. Primary care patients may be more likely to present with pain complaints (Garcia-Cebrian et al. Reference Garcia-Cebrian, Gandhi, Demyttenaere and Peveler2006). Others have reported, however, that rates of PPS are similar in primary care and psychiatric settings (Mathew et al. Reference Mathew, Weinman and Mirabi1981; Parmelee et al. Reference Parmelee, Katz and Lawton1991). The high prevalence of PPS has led some investigators to propose that pain symptoms may be a core feature of depressive illness (Simon et al. Reference Simon, VonKorff, Piccinelli, Fullerton and Ormel1999; Bair et al. Reference Bair, Robinson, Katon and Kroenke2003).

Outcomes of treatment for MDD may be poorer in the presence of PPS. Pain complaints may be characteristic of depression that is more serious, as evidenced by decreased productivity, increased absenteeism from work, more doctors' office visits and greater health care costs (Gameroff & Olfson, Reference Gameroff and Olfson2006). In a study of 512 patients treated with either duloxetine or placebo (Fava et al. Reference Fava, Mallinckrodt, Detke, Watkin and Wohlreich2004b), those with PPS were less likely to achieve remission over 9 weeks of treatment than those without. Physical symptoms, including pain, were less likely to resolve during treatment of MDD than emotional symptoms, and residual physical symptoms were associated with failure to achieve remission and greater likelihood of recurrence within 12 months.

Data indicating that patients with PPS have poorer outcome are based primarily upon studies of selected patient populations in psychiatric settings. Whether poorer outcomes would be seen among ‘real-world’ patients from both primary care and psychiatric settings remains unclear, as do contributions of other factors such as age, race, gender, chronicity or severity of depression, or the presence of chronic physical illness, to the possible association between PPS and poorer treatment outcome.

The ‘Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression’ (STAR*D) trial provides an excellent opportunity to help clarify the relationship between PPS and treatment outcome in out-patients with MDD who presented naturalistically for treatment. We previously reported that 77% of the complete sample (n=3702) that met criteria for MDD had PPS (Husain et al. Reference Husain, Rush, Trivedi, McClintock, Wisniewski, Davis, Luther, Zisook and Fava2007), that PPS were not associated with a history of chronic depression, and that there was no difference in the rates of PPS between those in primary or specialty care settings. In this report, we focus on the treatment response of the 2876 patients with MDD who completed their assessment and entered the first treatment step in STAR*D with the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) citalopram. We compare the outcome of patients with and without PPS treated in both primary and specialty (psychiatric) care settings, and examine the additional contributions of demographic and physical illness factors to treatment outcomes.

Method

Study overview and organization

The rationale and design of STAR*D have been described previously (Fava et al. Reference Fava, Rush, Trivedi, Nierenberg, Thase, Sackeim, Quitkin, Wisniewski, Lavori, Rosenbaum and Kupfer2003; Rush et al. Reference Rush, Fava, Wisniewski, Lavori, Trivedi, Sackeim, Thase, Nierenberg, Quitkin, Kashner, Kupfer, Rosenbaum, Alpert, Stewart, McGrath, Biggs, Shores-Wilson, Lebowitz, Ritz and Niederehe2004). Briefly, STAR*D aimed to define prospectively which of several treatments were most effective for out-patients with non-psychotic MDD who had an unsatisfactory clinical outcome to an initial and, if necessary, subsequent treatment(s). In this paper, we report on outcome data from the first step (level 1) treatment with the SSRI citalopram.

Study population

STAR*D enrolled out-patients aged 18–75 years who met DSM-IV criteria for non-psychotic MDD and had a score of ⩾14 (moderate severity) on the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAMD17; Hamilton, Reference Hamilton1960; Fava et al. Reference Fava, Rush, Trivedi, Nierenberg, Thase, Sackeim, Quitkin, Wisniewski, Lavori, Rosenbaum and Kupfer2003; Rush et al. Reference Rush, Fava, Wisniewski, Lavori, Trivedi, Sackeim, Thase, Nierenberg, Quitkin, Kashner, Kupfer, Rosenbaum, Alpert, Stewart, McGrath, Biggs, Shores-Wilson, Lebowitz, Ritz and Niederehe2004). Only self-declared out-patients seeking treatment and identified by their clinicians as having MDD were enrolled; to enhance generalizability of findings, no subjects were recruited with advertising and broadly inclusive selection criteria were used (Fava et al. Reference Fava, Rush, Trivedi, Nierenberg, Thase, Sackeim, Quitkin, Wisniewski, Lavori, Rosenbaum and Kupfer2003; Rush et al. Reference Rush, Fava, Wisniewski, Lavori, Trivedi, Sackeim, Thase, Nierenberg, Quitkin, Kashner, Kupfer, Rosenbaum, Alpert, Stewart, McGrath, Biggs, Shores-Wilson, Lebowitz, Ritz and Niederehe2004). The main exclusion criteria were resistance to an adequate antidepressant treatment trial during the current episode, pregnancy or intent to become pregnant in the near future, active breastfeeding and a primary psychiatric disorder requiring a different treatment (bipolar, psychotic, obsessive compulsive, or eating disorder). Subjects also were excluded if they had substance abuse/dependence that required in-patient treatment, or a general medical condition (GMC) that contraindicated medications used in the first two protocol treatment steps.

All subjects presented for treatment at one of 18 primary care or 23 specialty care settings across the USA. Three-quarters of the facilities were privately owned, and approximately two-thirds were freestanding (i.e. not hospital-based). Clinical research coordinators (CRCs) at each clinical site assisted participants and clinicians in subject screening and enrollment, protocol implementation and collection of clinical measures. A central group of research outcome assessors (ROAs) conducted telephone interviews to obtain primary outcomes.

All risks, benefits and adverse events associated with STAR*D participation were explained to participants, who provided written informed consent prior to study entry. The institutional review boards at the national coordinating center (Dallas, TX, USA), the data coordinating center (Pittsburgh, PA, USA), each clinical site and regional center, and the Data Safety and Monitoring Board of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH; Bethesda, MD, USA) approved and monitored the protocol.

Of the 3702 subjects meeting criteria for MDD who were the subject of the earlier report on PPS in MDD (Husain et al. Reference Husain, Rush, Trivedi, McClintock, Wisniewski, Davis, Luther, Zisook and Fava2007), 826 either did not complete the assessment or did not have a treatment visit following their enrollment. The remaining 2876 constitute the evaluable sample for this and previous reports (Trivedi et al. Reference Trivedi, Rush, Wisniewski, Nierenberg, Warden, Ritz, Norquist, Howland, Lebowitz, McGrath, Shores-Wilson, Biggs, Balasubramani and Fava2006b).

Baseline measures

At baseline, CRCs collected standard demographic information, self-reported psychiatric history and current GMCs as evaluated by the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (CIRS; Linn et al. Reference Linn, Linn and Gurel1968). CRCs administered the initial HAMD17 as well as the clinician-rated 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS-C16) and the patient completed the QIDS self-report (QIDS-SR16) (Rush et al. Reference Rush, Carmody and Reimitz2000, Reference Rush, Trivedi, Ibrahim, Carmody, Arnow, Klein, Markowitz, Ninan, Kornstein, Manber, Thase, Kocsis and Keller2003, 2006 a; Trivedi et al. Reference Trivedi, Rush, Ibrahim, Carmody, Biggs, Suppes, Crismon, Shores-Wilson, Toprac, Dennehy, Witte and Kashner2004).

Participants completed the Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire (PDSQ) (Zimmerman & Mattia, Reference Zimmerman and Mattia2001a, Reference Zimmerman and Mattiab), to estimate the presence of 11 potential concurrent DSM-IV disorders. Based on prior reports, we used thresholds with a 90% specificity in relation to the ‘gold standard’ diagnosis rendered by a structured interview to define the presence of concomitant Axis I disorders.

Treatment-masked ROAs, located remotely from all sites, used telephone interviews to complete the HAMD17 and the 30-item Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (IDS-C30) (Rush et al. Reference Rush, Gullion, Basco, Jarrett and Trivedi1996; Trivedi et al. Reference Trivedi, Rush, Ibrahim, Carmody, Biggs, Suppes, Crismon, Shores-Wilson, Toprac, Dennehy, Witte and Kashner2004), a validated instrument that uses unconfounded items (e.g. irritability and anxiety are separately rated) to measure both core diagnostic and associated symptoms during a telephone interview. Responses to items on these measures were used to determine the presence of atypical (Novick et al. Reference Novick, Stewart, Wisniewski, Cook, Manev, Nierenberg, Rosenbaum, Shores-Wilson, Balasubramani, Biggs, Zisook and Rush2005), melancholic (Khan et al. Reference Khan, Carrithers, Preskorn, Lear, Wisniewski, Rush, Stegman, Kelley, Kreiner, Nierenberg and Fava2006) and anxious (Fava et al. Reference Fava, Alpert, Carmin, Wisniewski, Trivedi, Biggs, Shores-Wilson, Morgan, Schwartz, Balasubramani and Rush2004a) symptom categories of MDD.

Definition of PPS

The presence of pain was determined using the IDS-C30 item no. 26, ‘somatic complaints’, from the baseline visit. This item is rated from 0 to 3, with 0 indicating no pain (‘no feeling of limb heaviness or pain’), 1 indicating mild symptoms (‘complains of headaches, abdominal, back, or joint pains that are intermittent and not disabling’), 2 indicating moderate symptoms (‘complains that the above pains are present most of the time’) and 3 indicating severe symptoms (‘functional impairment results from the above pains’).

Course of treatment measures

At each clinic visit, the QIDS-C16 and QIDS-SR16 ratings were obtained, and side-effects were assessed using three 7-point scales that evaluated frequency, intensity and global burden measures, respectively (Rush et al. Reference Rush, Fava, Wisniewski, Lavori, Trivedi, Sackeim, Thase, Nierenberg, Quitkin, Kashner, Kupfer, Rosenbaum, Alpert, Stewart, McGrath, Biggs, Shores-Wilson, Lebowitz, Ritz and Niederehe2004; Wisniewski et al. Reference Wisniewski, Rush, Balasubramani, Trivedi and Nierenberg2006).

Intervention

Citalopram was selected as the initial treatment for STAR*D based upon its demonstrated safety in elderly and medically fragile patients, once per day dosing, few dose adjustment steps, favorable drug–drug interaction profile and the relative absence of discontinuation symptoms (Rush et al. Reference Rush, Fava, Wisniewski, Lavori, Trivedi, Sackeim, Thase, Nierenberg, Quitkin, Kashner, Kupfer, Rosenbaum, Alpert, Stewart, McGrath, Biggs, Shores-Wilson, Lebowitz, Ritz and Niederehe2004). The goal of treatment was to achieve symptom remission (defined as QIDS-C16 score ⩽5 collected at each treatment visit), and to this end the treatment manual (www.star-d.org) guided clinicians to advance the citalopram dose in a vigorous yet tolerable manner. Citalopram was started at 20 mg/day (or a lower dose as necessary) and raised to 40 mg/day by weeks 2–4 and to 60 mg/day (final dose) by weeks 4–6. Dose adjustments were guided, however, by length of time at a particular dose, symptom changes and side-effect burden, so that patients with concomitant GMCs, substance abuse/dependence, other psychiatric disorders or sensitivity to medication side-effects could be titrated more slowly (Rush et al. Reference Rush, Fava, Wisniewski, Lavori, Trivedi, Sackeim, Thase, Nierenberg, Quitkin, Kashner, Kupfer, Rosenbaum, Alpert, Stewart, McGrath, Biggs, Shores-Wilson, Lebowitz, Ritz and Niederehe2004). Therefore, the final dose of citalopram and duration of treatment in this first step varied based upon clinical necessity.

The protocol recommended treatment visits at 2, 4, 6, 9 and 12 weeks (with an optional week 14 visit if needed). After a trial of optimal dose and duration, remitters and responders could enter 12-month naturalistic follow-up, but all who did not remit were encouraged to enter subsequent randomized trials (level 2 of STAR*D) (Rush et al. Reference Rush, Trivedi, Wisniewski, Stewart, Nierenberg, Thase, Ritz, Biggs, Warden, Luther, Shores-Wilson, Niederehe and Fava2006b; Trivedi et al. Reference Trivedi, Fava, Wisniewski, Thase, Quitkin, Warden, Ritz, Nierenberg, Lebowitz, Biggs, Luther, Shores-Wilson and Rush2006a). Patients could discontinue citalopram before 12 weeks if: (1) intolerable side-effects required a medication change; (2) an optimal dose increase was not possible because of side-effects or participant choice; or (3) significant symptoms (QIDS-C16 score ⩾9) were present after 9 weeks at maximally tolerated doses (Trivedi et al. Reference Trivedi, Rush, Wisniewski, Nierenberg, Warden, Ritz, Norquist, Howland, Lebowitz, McGrath, Shores-Wilson, Biggs, Balasubramani and Fava2006b).

Safety assessments

Side-effects were monitored with a multi-tiered approach (Nierenberg et al. Reference Nierenberg, Trivedi, Ritz, Burroughs, Greist, Sackeim, Kornstein, Schwartz, Stegman, Fava and Wisniewski2004) involving the CRCs, study clinicians, the interactive voice response system, the clinical manager, safety officers, regional center directors and the NIMH Data Safety and Monitoring Board.

Concomitant medications

Concomitant treatments for current GMCs, associated symptoms of depression (e.g. sleep and agitation) and citalopram side-effects (e.g. sexual dysfunction) were permitted based on clinical judgment, at study entry or during the course of treatment. Physicians also had the option of adding certain anxiolytic and/or sedative–hypnotic medications (excluding alprazolam) for brief periods based on clinical necessity. Other classes of central nervous system active medications, including stimulants, anticonvulsants, antipsychotics, other antidepressants (except trazodone ⩽200 mg at bedtime for insomnia), and psychotherapy specifically targeting depressive symptoms were prohibited.

Main outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was HAMD17 collected by ROAs using telephone-based structured interviews at entry and exit from citalopram treatment. The secondary outcomes included the QIDS-SR16 and Frequency, Intensity, and Burden of Side Effects Rating scale at each treatment visit.

Statistical analysis

Remission was defined by an HAMD17 obtained at study exit ⩽7 (or last obtained QIDS-SR16 score ⩽5). A reduction of ⩾50% in baseline QIDS-SR16 at the last assessment was defined as response. Subjects were considered not to have achieved remission if the exit HAMD17 was missing. Intolerance was defined as the subject either leaving treatment before 4 weeks or leaving at or after 4 weeks with intolerance as the reason specified. Statistical significance was ascribed as a two-sided p value <0.05. No adjustments were made for multiple statistical comparisons and the results should be interpreted accordingly.

Summary statistics are presented as means and standard deviations for continuous variables, and percentages for discrete variables. Parametric and non-parametric analysis of variance tests were calculated to compare continuous baseline symptomatic, historical, demographic and treatment features, between MDD patients with various levels of PPS. To compare categorical characteristics between MDD patients with various levels of PPS, χ2 tests were used. To determine if there was an independent effect of pain on outcomes, logistic regression models were used to adjust for confounding effects. In order to determine the set of covariates that may confound the association between outcome and group, the following procedure was employed. First, a bivariate model was estimated with an outcome regressed on pain (treated like an ordinal variable rather than a class variable). Second, a multivariate model was estimated with the same outcome regressed on pain and a potential confounder (a measure on which the pain groups differed, e.g. education). If the percentage difference between the parameter estimates for pain in both models exceeded ±10 then it was retained in the final model as a covariate. Times to first remission (QIDS-SR16 ⩽5) and first response (⩾50% reduction in baseline QIDS-SR16) were defined as the first observed point where subjects met specified criteria based upon clinic visit data. Log-rank tests were used to compare the cumulative proportion of participants with remission or response between MDD patients with various levels of PPS.

Results

Subject characteristics

Demographic and other characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1. The sample was predominantly white, female and had an average age of approximately 40 years. Most subjects suffered from chronic, recurrent, moderately severe MDD, with an average duration of current episode of more than 2 years, six prior episodes and HAMD17 of 21.8 (s.d.=5.2). Over half the participants were currently employed and over 40% were currently married. Over 60% received treatment for depression in psychiatric settings.

Table 1. Sociodemographic and clinical measures stratified by IDS-C30 pain item score

IDS-C30, 30-Item Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology – clinician-rated; s.d., standard deviation; HAMD17, 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; QIDS-SR16, 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology – self-rated.

Values are given as mean and s.d. or as n (% total n); sums may not equal total n due to missing data.

a Derived from the Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire.

b Derived from the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale.

c Less pain item.

Clinical features of subjects with and without pain

Of the subjects in the sample, 80% complained of PPS. More than one-third had mild complaints, but more than 25% reported pain present most of the time and approximately 20% complained of pain that interfered with function. Subjects with PPS were more likely to be female, to self-identify race or ethnicity as African-American or Hispanic, to have fewer years of education, to be unemployed, to be married and to have either no insurance or public insurance. More of those with PPS were treated in primary care than the proportion in the overall sample (Table 1).

Subjects with PPS had significantly greater severity of depressive symptoms at initiation of treatment than did those without PPS. Those with greater levels of pain complaints had more severe depressive symptoms than those with either lesser levels of PPS or no pain complaints, as well as a greater number of Axis I co-morbidities. There also were strong associations between the presence of PPS in those entering treatment and medical illness burden as measured by the CIRS. Those reporting greater severity of PPS had a greater number of categories of GMCs and severity of illness(es) than those without PPS. Subjects with PPS also were significantly more likely to report four or more different categories of illness (p<0.0001) (Table 1). Those categories of illness most likely to be reported as positive by those with PPS included musculoskeletal/integumental, neurological, upper gastrointestinal, genito-urinary, hematopoietic and respiratory.

There were no significant differences in current suicide risk according to level of pain complaints. Subjects who endorsed PPS were more likely, however, to have anxious, atypical or melancholic features of depression. Those reporting higher degrees of pain also were more likely to meet criteria for a greater overall number of co-morbid Axis I conditions (Table 1).

Response to treatment and reports of pain

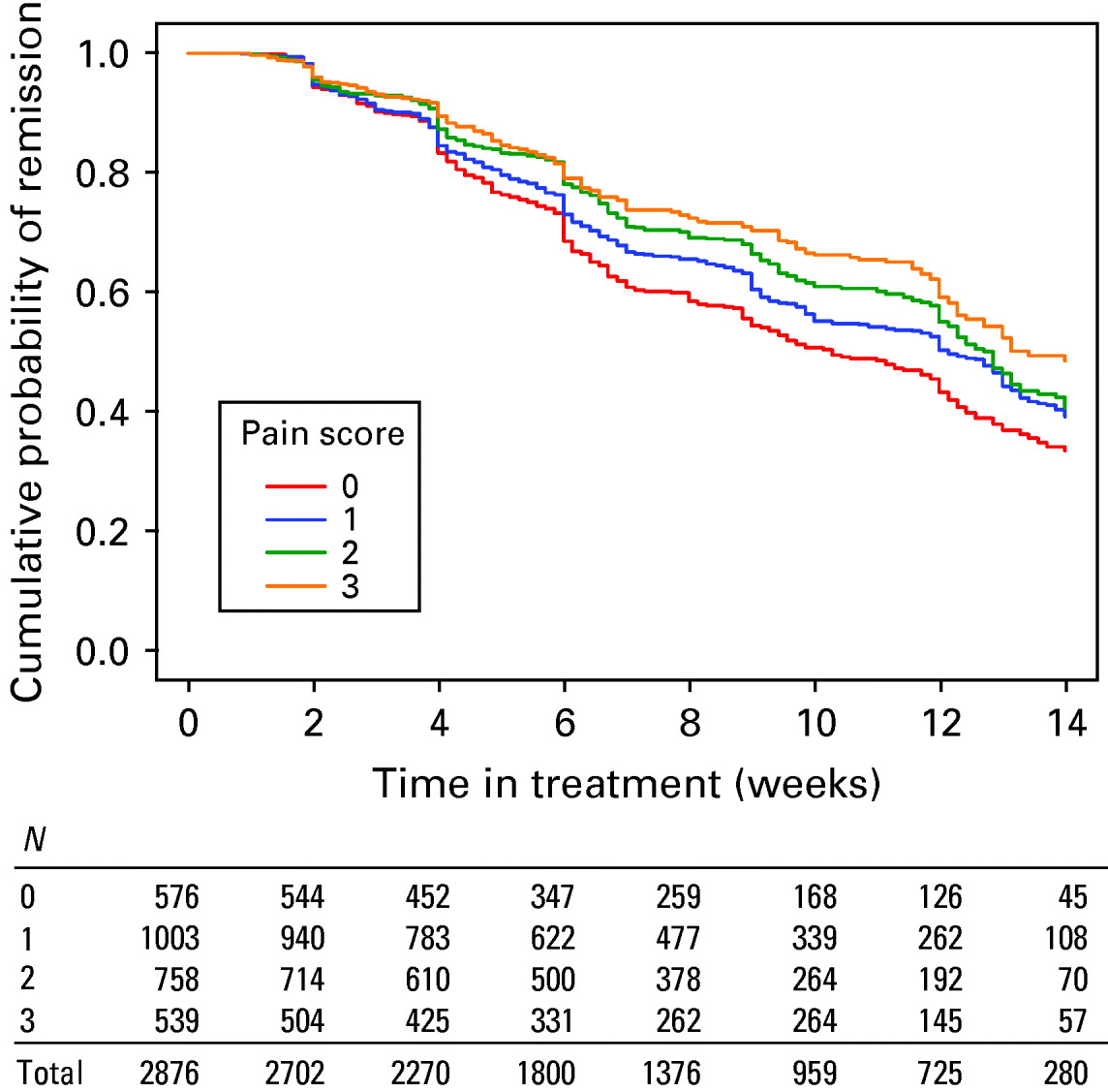

Time to first remission (Fig. 1) and response (Fig. 2) differed significantly according to the level of PPS. Those without reports of pain on average achieved both remission and response sooner than those reporting PPS. Those with higher degrees of pain complaints achieved response and remission more slowly than those with lesser PPS. Differences in outcome could not be accounted for by a difference in treatment intensity: there was no difference in mean citalopram dose or number of weeks in treatment between those reporting and not reporting PPS. Patients with PPS received as intense treatment as those without PPS despite the fact that they had significantly more intense, frequent and burdensome side-effects from citalopram (Table 2). They were much more likely to report that side-effects interfered moderately or severely with their ability to function, but were only slightly more likely to exit the study due to medication intolerance.

Fig. 1. Clinical response patterns stratified by 30-item Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology pain item score and time in treatment table. Log rank χ2(3)=20.35 (p=0.0001).

Fig. 2. Clinical remission patterns stratified by 30-item Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology pain item score and time in treatment table. Log rank χ2(3)=27.28 (p<0.0001).

Table 2. Treatment and outcome measures stratified by IDS-C30 pain item score

IDS-C30, 30-Item Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology – clinician-rated; s.d., standard deviation; HAMD17, 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; OR, odds ratio; QIDS-SR16, 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology – self-rated.

Values are given as mean and s.d. or as n (% total n); sums may not equal total n due to missing data.

a Frequency, Intensity, and Burden of Side Effects Rating Scale.

b Terminated study up to week 4 for any reason or after week 4 citing intolerable side-effects.

c Adjusted only for baseline IDS-C30 less pain item.

d Adjusted for all variables below except baseline IDS-C30 less pain item.

e All models adjust for education, insurance, number of Axis I and III co-morbidities, baseline IDS-C30 less pain item, and anxious features. All models except QIDS-SR16 exit score adjust for race. All models except QIDS-SR16 remission adjust for employment. Additional adjustments: HAMD17 remission, gender; QIDS-SR16 percentage change and QIDS-SR16 response, gender and recurrent depression.

Patients reporting PPS were less likely to experience remission or response, and more likely to experience more severe depressive symptoms at the end of citalopram treatment (Table 2).

Logistic regression showed that subjects with higher degrees of PPS had significantly lower likelihood of response or remission than either those without pain complaints, or those with lower levels of PPS. This difference was not simply a function of severity of depression; the difference in outcome persisted even after adjustment for baseline severity of depression as indicated by the response rate using the QIDS-SR or the QIDS-SR exit score or percentage change. Logistic regression also showed that the baseline symptomatic, historical and demographic characteristics independently associated with PPS were race, gender, ethnicity, CIRS count and baseline severity as measured by HAMD17. Specifically, Caucasians and men had lower odds of more severe PPS than others, while African-Americans and Hispanics had higher odds, as did those with more GMCs and greater severity of depression. After adjusting for these potentially confounding factors, patients with PPS continued to suffer worse outcomes than those without PPS, although the differences no longer were statistically significant (Table 2).

Discussion

This report represents the largest prospective examination of the association between complaints of PPS and treatment outcomes in MDD. The current results confirm findings from previous studies and indicate that patients who present with PPS are less likely to respond or remit after treatment, and that increasing levels of pain severity were associated with progressively decreasing likelihood of improvement. The associations between treatment outcome and PPS were not solely a function of severity of depression because they persisted even after controlling for baseline level of depression. The magnitude of this difference in outcome attributable to PPS was relatively large when comparing those with no PPS to those with the most severe complaints (11.1% difference in remission rates). Poor outcomes in this population, however, are complex; presence and severity of PPS were associated with African-American or Hispanic race or ethnicity, female gender, greater physical illness burden and greater baseline severity of depression. After adjustment for these factors, patients with PPS still suffered numerically worse treatment outcome, although the difference was no longer statistically significant. This indicates that presence and severity of PPS are not, but are associated with factors that are, predictors of poor outcome.

The presence of these symptoms clearly indicates the presence of a depressive illness that is likely to be more resistant to an adequate course of treatment with an SSRI. What is less clear is why this is the case. While there may be neurobiological mechanisms underlying the poorer treatment outcomes of MDD patients with PPS, the present results also indicate that psychosocial factors may play a prominent role.

The poorer outcomes among patients with PPS do not reflect less intensive SSRI treatment because the medication dosages did not differ significantly between those with and without PPS; those who complained of pain prior to treatment simply were less likely to improve significantly or get well. The finding that most patients with PPS continued with treatment is noteworthy because patients with PPS were significantly more likely to report high side-effect frequency, intensity and burden than those without pain complaints. Interestingly, these patients were only slightly more likely to exit due to medical intolerance and had the same average duration of treatment. There was no direct measure of medication compliance in this study (such as pill counts), so we cannot be certain that the patients reporting PPS took the prescribed doses of medication. The fact that so many remained in active treatment, however, suggests that they were adherent with many aspects of the treatment plan. This finding suggests that patients with PPS may be more willing or motivated to continue with antidepressant medication than those without PPS even in the presence of side-effects.

Subjects with PPS had a number of characteristics of MDD that are associated with poorer outcome from antidepressant treatment (Fava et al. Reference Fava, Alpert, Carmin, Wisniewski, Trivedi, Biggs, Shores-Wilson, Morgan, Schwartz, Balasubramani and Rush2004a, Reference Fava, Rush, Alpert, Balasubramani, Wisniewski, Carmin, Biggs, Zisook, Leuchter, Howland, Warden and Trivedi2008; Novick et al. Reference Novick, Stewart, Wisniewski, Cook, Manev, Nierenberg, Rosenbaum, Shores-Wilson, Balasubramani, Biggs, Zisook and Rush2005; Khan et al. Reference Khan, Carrithers, Preskorn, Lear, Wisniewski, Rush, Stegman, Kelley, Kreiner, Nierenberg and Fava2006). They were significantly more likely to have features of anxious depression and to meet criteria for a co-morbid anxiety disorder. They also were significantly more likely to have atypical or melancholic features of depression than those without pain complaints. The STAR*D sample contained a high proportion of patients suffering from chronic and recurrent MDD, but the patients with PPS were no more likely than the overall sample to have chronic or recurrent depressive illness.

Patients with PPS had a greater average number and severity of physical illnesses and, not surprisingly, the three categories of illness that were highly represented among those with PPS were musculoskeletal/integumental, neurological and upper gastrointestinal illnesses. These would be consistent with illnesses such as arthritis, neuropathy and ulcers or gastric reflux. Patients with PPS also had a higher proportion and severity of illnesses affecting the genito-urinary and respiratory systems, which could be associated with the higher rate of somatic anxiety features among these patients (Husain et al. Reference Husain, Rush, Trivedi, McClintock, Wisniewski, Davis, Luther, Zisook and Fava2007; Fava et al. Reference Fava, Rush, Alpert, Balasubramani, Wisniewski, Carmin, Biggs, Zisook, Leuchter, Howland, Warden and Trivedi2008). The reports of higher medication side-effects in patients with PPS could be consistent both with their higher physical illness burden and the presence of greater levels of anxiety. Because the CIRS does not yield more specific data on particular medical illnesses, it is not possible to examine this finding in greater detail in this trial.

Few previous studies have examined the relationship between patients' overall treatment outcome and complaints of PPS. Bair et al. (Reference Bair, Robinson, Eckert, Stang, Croghan and Kroenke2004) studied 573 patients with MDD treated with one of three SSRIs (fluoxetine, paroxetine or sertraline). They found that those patients with PPS at baseline were significantly less likely to respond to SSRI treatment at 3 months than those without pain complaints. Geerlings et al. (Reference Geerlings, Twisk, Beekman, Deeg and van Tilburg2002) compared recovery from depression of 119 patients with and 102 patients without pain complaints, all between the ages of 55 and 85 years and drawn from the Longitudinal Aging Study of Amsterdam. They reported that those without pain complaints were significantly more likely to recover over the course of 3-year follow-up than those complaining of pain.

One question is whether this apparent association between pain complaints and outcome is specific for pain, or whether it might be a more general association between the presence of somatic symptoms and outcome. This question was addressed in part by Karp et al. (Reference Karp, Scott, Houck, Reynolds, Kupfer and Frank2005), who examined 141 patients with recurrent MDD and studied the effects of both complaints of pain and somatization [as defined by Hopkins Symptom Checklist (SCL-90) items] on likelihood of and time to remission (as defined by final HAMD17 ⩽7). They found that patients with pain complaints were 10% less likely, and on average took 5 weeks longer, to achieve remission than those without pain complaints. There was not a similar association for somatization, suggesting that this association may be specific to PPS.

Although pain complaints are associated with poorer outcome from treatment for depression, controlled studies and case reports have shown that antidepressant medications may help decrease pain, both in patients with depression and in those with pain alone (Krell et al. Reference Krell, Leuchter, Cook and Abrams2005). There is evidence, however, that either noradrenergic or mixed reuptake inhibitor antidepressants may be more effective for the relief of PPS than SSRIs (Krell et al. Reference Krell, Leuchter, Cook and Abrams2005; Sindrup et al. Reference Sindrup, Otto, Finnerup and Jensen2005; Atkinson et al. Reference Atkinson, Slater, Capparelli, Wallace, Zisook, Abramson, Matthews and Garfin2007; Jann & Slade, Reference Jann and Slade2007). It may in fact be the case that patients treated with SSRIs are more likely to be left with residual symptoms of pain. Greco et al. (Reference Greco, Eckert and Kroenke2004) examined a variety of somatic complaints among patients with MDD treated with an SSRI; these complaints included limb and back pain, as well as headache, sleep problems and fatigue. Pain complaints were the least likely symptoms to resolve during SSRI treatment.

Painful symptoms themselves are not a prominent feature of the diagnostic criteria for any depressive disorder in DSM-IV. It is possible, however, that painful symptoms may be associated with the overall likelihood of significant symptom reduction in depression. This is consistent with the findings of Fava et al. (Reference Fava, Mallinckrodt, Detke, Watkin and Wohlreich2004b), who reported that those MDD subjects who had a greater than 50% reduction in pain complaints were twice as likely to achieve remission than those with less than a 50% reduction. Some findings indicate that it is only the most severe PPS that are likely to interfere with recovery from depression. Mavandadi et al. (Reference Mavandadi, Ten Have, Katz, Durai, Krahn, Llorente, Kirchner, Olsen, Van Stone, Cooley and Oslin2007) studied 524 adults aged 60 years and older treated for depression, and examined the relationship between the severity of pain symptoms and recovery from depression. They found that only when pain interfered with function at work and home did it also interfere with recovery from depression. This is related to the findings of Lin et al. (Reference Lin, Tang, Katon, Hegel, Sullivan and Unutzer2006), who studied 1001 patients aged 60 years or older suffering from MDD and/or dysthymia along with arthritis. They reported that systematic depression management demonstrated an advantage in reducing pain symptoms only among those patients with lower initial pain severity. Thus, it appears that higher levels of pain may be more resistant to amelioration by antidepressant treatment, and that those patients with higher levels of pain may be less likely to experience remission from antidepressant treatment.

There are two primary limitations of the current study to be noted. First, patients with PPS were identified based solely on a single item with one of four possible responses (pain was absent, or present with three grades of severity). The reliability of this item for detecting pain complaints has not been studied, and its sensitivity and specificity is not established. It would be useful in future studies to examine pain with more detailed instruments that would more completely characterize the nature of the complaints, including the duration, etiology and location of pain as well as treatment history. Second, treatment consisted of a single SSRI, citalopram. It is unknown whether remission or response rates would have been higher if the patients had been treated with a medication with another mechanism of action.

Future studies should specifically examine a biopsychosocial model to explain poorer outcome in these patients. Patients who reported PPS also complained of greater medication side-effect burden, greater functional impairment due to physical illness and were more likely to meet PDSQ criteria for somatoform disorder or hypochondriasis. It is possible that these reports of higher physical distress among patients complaining of pain may reflect augmented central nervous system pain processing. Recent findings indicate that patients with MDD have increased cerebral blood flow in response to noxious stimuli in brain regions that process the affective and cognitive components of pain (Graff-Guerrero et al. Reference Graff-Guerrero, Pellicer, Mendoza-Espinosa, Martinez-Medina, Romero-Romo and de la Fuente-Sandoval2008). On the other hand, in the present study, several demographic and socio-economic factors were independently associated with the presence of PPS and, after adjusting for these factors, patients with PPS no longer had significantly worse outcomes. Poorer outcomes therefore may reflect the cumulative effect of psychosocial and neurobiological factors. In the final analysis, elucidation of the linkages between the presence and intensity of PPS and poorer outcome could help direct selection of the most effective treatments for patients with these symptoms in MDD.

Acknowledgements

This project has been funded with Federal funds from the NIMH, National Institutes of Health, under contract N01MH90003 to the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas (principal investigator A.J.R.) [ClinicalTrials.gov no. NCT00021528].

The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products or organizations imply endorsement by the US Government.

Declaration of Interest

A.F.L. has provided scientific consultation to or served on advisory boards for Aspect Medical Systems, Eli Lilly & Company, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer Pharmaceuticals and Takeda Pharmaceuticals. He serves on the speakers' bureaus for Eli Lilly & Company and Wyeth Pharmaceuticals. He has received research/grant support from the NIMH, the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, Aspect Medical Systems, Eli Lilly & Company, MedAvante, Merck & Co., Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Inc. and Vivometrics. He owns stock in Aspect Medical Systems. M.M.H. has served on the speakers' bureaus for Astra Zeneca and Bristol–Myers Squibb. He has received research/grant support from Advanced Neuromodulations Systems, Cyberonics Inc., Magstim, NIMH, Neuronetics and Stanley Medical Research Institute. I.A.C. has served as an advisor and consultant for Ascend Media, Bristol–Myers Squibb, Cyberonics Inc. and Janssen. He has served on the speakers' bureaus for Bristol–Myers Squibb, Medical Education Speakers Network, Pfizer Pharmaceuticals Inc. and Wyeth Pharmaceuticals. He receives research support from Aspect Medical Systems, Cyberonics Inc., Eli Lilly & Company, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer Inc. and Sepracor. M.H.T. has received research support from, or served as a consultant to, or has been on the speakers' boards of the following: Abdi Brahim; Abbott Laboratories, Inc.; Akzo (Organon Pharmaceuticals Inc.); AstraZeneca; Bayer; Bristol–Myers Squibb Company; Cephalon, Inc.; Corcept Therapeutics, Inc.; Cyberonics, Inc.; Eli Lilly & Company; Fabre Kramer Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Forest Pharmaceuticals; GlaxoSmithKline; Janssen Pharmaceutica Products, LP; Johnson & Johnson PRD; Meade Johnson; Merck; NIMH; National Alliance for Research in Schizophrenia and Depression; Neuronetics; Novartis; Parke-Davis Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Pfizer Inc.; Pharmacia & Upjohn; Predix Pharmaceuticals; Sepracor; Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; VantagePoint; Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories. S.R.W. has provided scientific consultation to Cyberonics Inc. (2005–6), ImaRx Therapeutics, Inc. (2006) and Bristol–Myers Squibb Company (2007). W.S.G. has served on the speakers' bureaus for GlaxoSmithKline and Pfizer. He has also received honoraria from GlaxoSmithKline and Pfizer Inc. Additionally he has received research support from Abbott, Aspect Medical Systems, Forest Pharmaceuticals, Janssen, Neuronetics, Novartis Pharmaceuticals and Pfizer. M.F. has received research support from Abbott Laboratories, Alkermes, Aspect Medical Systems, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, Cephalon, Eli Lilly & Company, Forest Pharmaceuticals Inc., GlaxoSmithKline, J & J Pharmaceuticals, Lichtwer Pharma GmbH, Lorex Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Organon Inc., PamLab, LLC, Pfizer Inc., Pharmavite, Roche, Sanofi/Synthelabs, Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Inc. and Wyeth–Ayerst Laboratories. He has provided scientific consultation to or served on advisory boards for Aspect Medical Systems, AstraZeneca, Bayer AG, Best Practice Project Management, Inc., Biovail Pharmaceuticals, Inc., BrainCells, Inc., Bristol–Myers Squibb Company, Cephalon, Compellis, Cypress Pharmaceuticals, Dov Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly & Company, EPIX Pharmaceuticals, Fabre-Kramer Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Forest Pharmaceuticals Inc., GlaxoSmithKline, Grunenthal GmBH, Janssen Pharmaceutica, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, J & J Pharmaceuticals, Knoll Pharmaceutical Company, Lundbeck, MedAvante, Inc., Merck, Neuronetics, Novartis, Nutrition 21, Organon Inc., PamLab, LLC, Pfizer Inc., PharmaStar, Pharmavite, Roche, Sanofi/Synthelabo, Sepracor, Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Somaxon, Somerset Pharmaceuticals, Takeda and Wyeth–Ayerst Laboratories. He has been on speakers' bureaus for AstraZeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol–Myers Squibb Company, Cephalon, Eli Lilly & Company, Forest Pharmaceuticals Inc., GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Organon Inc., Pfizer Inc., PharmaStar and Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories. He has equity holdings with Compellis and MedAvante. A.J.R. has received research support from the NIMH and the Stanley Medical Research Institute. He has been on the advisory boards and/or consultant for Advanced Neuromodulation Systems, Inc., AstraZeneca, Best Practice Project Management, Inc., Bristol–Myers Squibb/Otsuka Company, Cyberonics, Inc., Forest Pharmaceuticals, Gerson Lehman Group, GlaxoSmithKline, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Magellan Health Services, Merck & Co., Inc., Neuronetics, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Ono Pharmaceutical, Organon USA Inc., Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, Pamlab, Pfizer Inc., Transcept Pharmaceuticals, Urban Institute and Wyeth–Ayerst Laboratories Inc. He has been on the speakers' bureaus for Cyberonics, Inc., Forest Pharmaceuticals, Inc. and GlaxoSmithKline. He has equity holdings (excluding mutual funds/blinded trusts) in Pfizer Inc., has royalty income affiliations with Guilford Publications and Healthcare Technology Systems, Inc., and has received a stipend for role as treasurer from the Society of Biological Psychiatry.