All psychiatric and substance use disorders are familial (McGuffin et al. Reference McGuffin, Owen, O'Donovan, Thapar and Gottesman1994; Kendler & Eaves, Reference Kendler and Eaves2005). An old yet central question for the field is the degree to which this aggregation results from genetic v. environmental factors. Because these questions cannot be addressed by controlled experiments, psychiatric genetics has had to rely on ‘experiments of nature’ to address this problem, of which two – twin and adoption studies – have been predominant. Because of the increasing availability of twin registries (Hur & Craig, Reference Hur and Craig2013) and the declining rates of and the strict legal protections surrounding adoption, twin studies have become the dominant method.

The validity of the twin method has long been questioned, with critics charging that the resulting heritability estimates are substantially inflated (Jackson, Reference Jackson and Jackson1960; Lewontin et al. Reference Lewontin, Rose and Kamin1985; Pam et al. Reference Pam, Kemker, Ross and Golden1996; Joseph, Reference Joseph2002). Twins also have a distinct intra-uterine experience and form, it is claimed, a unique psychological relationship so that results derived from them cannot be extrapolated to more typical human populations. Many efforts have been made to empirically address these criticisms (Kendler, Reference Kendler1983; Kendler & Prescott, Reference Kendler and Prescott2006; Barnes et al. Reference Barnes, Wright, Boutwell, Schwartz, Connolly, Nedelec and Beaver2014; LoParo & Waldman, Reference LoParo and Waldman2014) but the debate continues as witnessed by a recent review in a prominent criminology journal, which argued that twin studies were so flawed that their further use should be banned (Burt & Simons, Reference Burt and Simons2014). The problem of the accuracy of twin heritability estimates has recently taken on a new urgency given increasing efforts to understand the origins of the ‘missing heritability’ problem – the differences in heritability estimates derived from twin studies v. from statistical tools applied to genome-wide molecular variants [Manolio et al. Reference Manolio, Collins, Cox, Goldstein, Hindorff, Hunter, McCarthy, Ramos, Cardon, Chakravarti, Cho, Guttmacher, Kong, Kruglyak, Mardis, Rotimi, Slatkin, Valle, Whittemore, Boehnke, Clark, Eichler, Gibson, Haines, Mackay, McCarroll and Visscher2009; Lee et al. Reference Lee, Wray, Goddard and Visscher2011; Cross-Disorder Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (PGC-CDG) 2013; Golan et al. Reference Golan, Lander and Rosset2014; Goldman, Reference Goldman2014; Wray & Maier, Reference Wray and Maier2014].

In this report, we present a new design for addressing the sources of familial aggregation relying on typical sibling relationships: full-, half- and step-siblings. We apply this design to drug abuse (DA), alcohol use disorder (AUD) and criminal behavior (CB). Three aspects of our design are novel. First, because of the records available in Sweden, we know the siblings’ cohabitation history and so can directly assess their household-level shared environmental exposure during childhood.

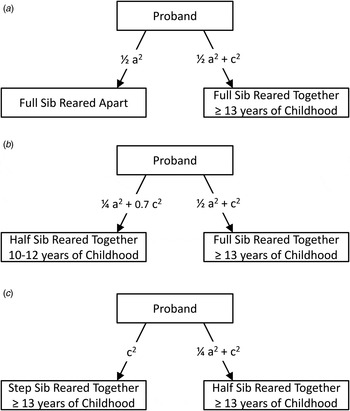

Second, rates of drug, criminal and alcohol problems vary in different family constellations, being substantially lower in intact full-siblings than in ‘broken’ half- or step-sib families. Therefore, instead of comparing aggregate correlations for different types of relationships, we identify informative sibling trios consisting of one proband and two siblings who differ in the degree of their genetic resemblance and/or environmental sharing with the proband (Fig. 1). In each trio, we can predict the expected correlations in liability from which we estimate genetic and environmental effects. Such sibships each represent a natural experiment. Because our comparisons are all within sibships, we control for background familial factors that can differ across family constellations.

Fig. 1. Examples of (a) a proband with a full-sibling with whom he had been reared with for ⩾13 years of his childhood (up to the age of 16 years) and a full-sibling with whom he never cohabitated; (b) a proband with a full-sibling with whom he had been reared with for ⩾13 years of his childhood and a half-sibling with whom he had been reared for 10–12 years of his childhood; and (c) a proband with a half-sibling and a step-sibling, both of whom he had lived with for ⩾13 years of his childhood.

Third, we examine a range of such informative sibling trios, and focus in particular on those that include a proband and either one full-sibling or one half-sibling reared together with the proband. By exploring the stability of our estimates of genetic and environmental effects across trio types, we can evaluate the validity of our assumptions. Finally, we fit structural equation models jointly in a multi-group model to our different sibling trios. This permits us to obtain both an aggregate estimate to compare with estimates derived from twins in the same population and to test formally whether our estimates from the different kinds of sibling trios differ significantly from one another.

Method

We used linked data from multiple Swedish nationwide registries and healthcare data. For details and for definitions of CB, DA and AUD, see online Supplementary material. We secured ethical approval for this study from the Regional Ethical Review Board of Lund University (no. 2008/409).

Sample

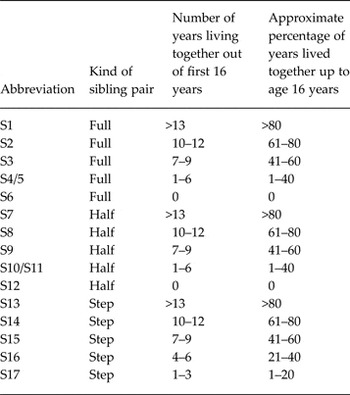

The source population consisted of all individuals born in Sweden between 1960 and 1990, and who had not emigrated or died before the age of 16 years, which we define as childhood. We started with a putative proband from this population and selected all his/her same-sex full-, half- and step-siblings with a maximum of 10 years age difference. A step-sibling was defined as an individual residing in the same household as the proband during childhood who was not genetically related up to first cousins. As outlined in Table 1, we then considered 17 types of sibling pairs as a function of the genetic relationship (full-, half- or step-sib) and six levels of cohabitation (defined as residing in the same household) during childhood: ⩾13 years (termed ‘reared together’), 10–12 years, 7–9 years, 4–6 years, 1–3 years and 0 years (for full- and half-sibs only). We ended up with 15 functional categories, as, because of small numbers, we combined full- and half-siblings who cohabitated 1–3 and 4–6 years (Table 1).

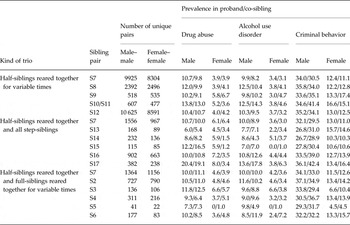

Table 1. Types of sibling pairs that make up the sibling trios

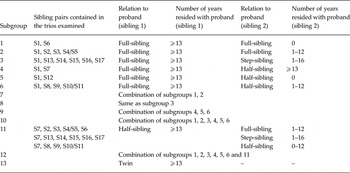

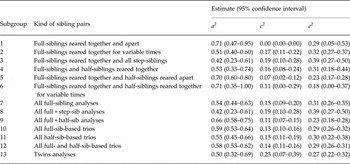

Trios were then selected where the proband had a different type of relationship with each of the two co-siblings (Fig. 1). Our analyses examined the two proband–sibling relationships in each trio and we did not consider the relationship of the two non-proband siblings. As outlined in Table 2, we examined two major groups of trios in which the first proband–sibling relationship was that of: (i) a reared-together full-sibling pair; and (ii) a reared-together half-sibling pair. We call these, respectively, full-sibling and half-sibling-based trios. In the larger sample of full-sibling-based trios (66 480 unique male and 67 101 unique female probands), we formed six subgroups of pairs, listed in subgroups 1–6 in Table 2. Subgroups 7–9 then represented all full-sibling-based trios where the second proband–sibling pair was, respectively, a full-, step- and half-sibling. Subgroup 10 included all the full-sibling-based trios analysed together. Because of the smaller sample size of half-sibling-based trios (13 322 unique male and 11 232 unique female probands), subgroup 11 included all the half-sibling-based trios analysed together and group 12 all trios examined together. All the analyses were stratified based on sex. We required that all three individuals within the trio were of the same sex.

Table 2. Subgroups of sibling trios

Statistical analyses

As in classical twin modeling, we assume a liability threshold model with three sources of liability: additive genetic (A), shared environment (C) and unique environment (E). We assumed that full-siblings share on average half and half-siblings a quarter of their genes identical by descent and step-siblings were genetically uncorrelated with each other. Additionally we assumed that shared environment was a function of the number of years residing together in the same household during childhood. We assume C to equal 1 for all individuals residing ⩾13 years in the same household, 0.7 for 10–12 years; 0.5 for 7–9 years; 0.3 for 4–6 years; 0.1 for 1–3 years and finally 0 for 0 years. A sibling pair could be included in several trios. However, as we do not estimate the correlation between siblings no. 1 and no. 2 in the trio, the pair will be included only once in each model.

Our estimation procedures for each pair of sibling types were straightforward. In each case, we had two equations (the correlations for the given phenotype in two different kinds of sibling pairs predicted by different proportions of A and C) and two unknowns: A and C. Thus, in a saturated model, we could always derive estimates of A and C from these results with E as a residual term defined as e 2 =1 − (a 2 + c 2). We only included pairs of relationships in our analyses that provided unique solutions.

To facilitate comparisons across models, we present only results from the full model, that is, containing estimates of A, C and E. Prior simulations have suggested that parameter estimates from a full model are typically more accurate than those from submodels (Sullivan & Eaves, Reference Sullivan and Eaves2002). Model fitting was done using Mplus version 7.2 with the delta parameterization and the weighted least squares means and variance (WLSMV) as the fit function (Muthén & Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén2007).

We utilized fit indices, i.e. the Tucker–Lewis index (Tucker & Lewis, Reference Tucker and Lewis1973), the comparative fit index (Bentler, Reference Bentler1990) and the root mean square error of approximation (Steiger, Reference Steiger1990), to assess the model's balance of explanatory power and parsimony.

Results

Sample

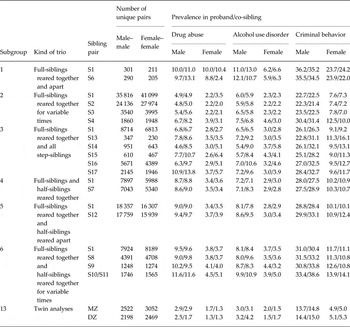

Table 3 shows the number of informative trios containing a full-sibling reared-together pair as well as the prevalence for DA, AUD and CB in each of the siblings. Sample sizes varied widely across trios. The most common informative trios were subgroup 2 where one proband–full-sib pair was reared together (S1) and the other pair cohabitated 60–79% (S2), 40–59% (S3) or 1–39% of their childhood (S4). The second most common was subgroup 5 where the proband–full-sib pair was reared together and the proband–half-sib pair was reared separately. Particularly rare was subgroup 1 where the one proband–full-sib pair was reared together and the other full-sib–sib pair was raised separately. The prevalence of the three syndromes – all of which were more common in males than females – differed widely across family type. For example, the prevalence of AUD in females was about 2% in the largely intact subgroup 2 families, 3–5% in the subgroup 3 families and 6% in the unusual subgroup 1 families. For DA in males, parallel values were 4–5%, 7–11% and 10–13%. Table 4 presents similar information for the half-sib-based trios.

Table 3. Sample sizes for full-sibling reared-together-based sibling trios and twin pairs

MZ, Monozygotic; DZ, dizygotic.

Table 4. Sample sizes for half-sibling reared-together-based sibling trios all making up subgroup 11

Heritability

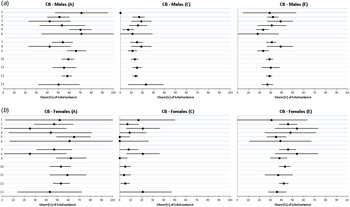

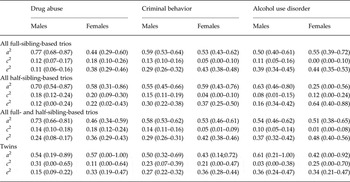

Summary results for all analyses are presented in detail in the forest plots (Figs 2a–4b ) and the summary (Table 5). We present results in detail for CB in males in Table 6 (and Fig. 2a ) as this is our most common phenotype where we have greatest statistical power. We examined the fit of three comparative models: (i) the six full-sib-based trio combinations estimated separately or together; (ii) the three half-sib-based trio combinations estimated separately or together; and (iii) the aggregate estimates obtained from the full-sib- and half-sib-based analyses. In all cases, as seen in the online Supplementary material, the joint estimates had similar or superior fits on at least two of the three fit indices, suggesting that the estimates were statistically homogeneous.

Fig. 2. (a) Parameter estimates for additive genetic effects (A), shared environmental effects (C) and unique environmental effects (E) estimates from various kinds of sibling trios for criminal behavior (CB) in males. The numbers given at the left side of the figure correspond to the model number outlined in Table 2. The first six lines depict results for all the subtypes of full-sibling-based trios. The next three lines reflect the three major subgroups of full-sibling-based trios. The next three separated lines depict, respectively, results for all full-sib-based trios, all half-sib-based trios and the results for all the sibling trios (full-sib + half-sib-based). The final line reflects the results from twin analyses. (b) Parameter estimates for additive genetic effects (A), shared environmental effects (C) and unique environmental effects (E) estimates from various kinds of sibling trios for CB in females. The numbers given at the left side of the figure correspond to the model number outlined in Table 2. Values are estimates, with 95% confidence intervals represented by horizontal bars.

Table 5. Estimates for additive genetic (a 2), shared environmental (c 2) and unique environmental effects (e 2) from sibling trios and twins for drug abuse, criminal behavior and alcohol use disorder

Data are given as estimate (95% confidence interval).

Table 6. Criminal behavior in males

CB

Table 6 provides detailed results for CB in males, summarized in Fig. 2a . We focus here on estimates of heritability (a 2). Our first sample (subgroup 1 in Table 2) is a rare trio type so the resultant estimate for a 2 for CB – 0.71 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.47–0.95] – is known imprecisely. Our second type of trios – (subgroup 3) – is more common and the resultant heritability estimate has narrower CIs (0.51, 95% CI 0.40–0.60). Because of the relative rarity of step-sibs, we considered all the full-sib–step-sib trios together in subgroup 3 and obtained an a 2 estimate of 0.42 (95% CI 0.23–0.61). For subgroups 4, 5 and 6 (full-sibling/half-sibling trios), we obtain estimates of the heritability of CB of 0.53 (95% CI 0.33–0.74), 0.70 (95% CI 0.60–0.80) and 0.71 (95% CI 0.35–1.00), respectively.

For subgroups 7 (full-sibling trios, combined across all cohabitation periods), 8 (full-/step-sibling trios) and 9 (full-/half-sibling trios across all cohabitation periods), heritability estimates for CB were similar with overlapping CIs: 0.54 (95% CI 0.44–0.63), 0.42 (95% CI 0.23–0.61) and 0.66 (95% CI 0.58–0.75), respectively. Subgroup 10 involved fitting a model across all the individual estimates from subgroups 1 to 6, constraining to equality estimates of a 2, c 2 and e 2 which performed well with our fit indices (online Supplementary material). The resulting estimated heritability of CB in males was 0.59 (95% CI 0.53–0.64).

Subgroup 11 presents the results from all half-sibling reared-together-based trios which estimated a 2 for CB in males at 0.55 (95% CI 0.45–0.66). Fit indices indicated that the full- and half-sibling-based trios could be combined and produced a heritability estimate, for subgroup 12, of 0.58 (95% CI 0.53–0.62). The final row of Table 6 presents the results from monozygotic (MZ) and dizygotic (DZ) twins where a 2 for CB in males was estimated at 0.50 (95% CI 0.32–0.69).

Results from all our trio subgroups for CB in females are presented in Fig. 2b and key findings summarized in Table 5. (In Figs 2a and 3b , the number on the lines on the y-axis corresponds to the subgroup number in Table 2.) Heritability estimates from the three subgroups of the full-sib-based trios (7, 8 and 9) were, respectively, 0.47 (95% CI 0.31–0.63), 0.25 (95% CI 0.00–0.58) and 0.62 (95% CI 0.49–0.76). Modeling all the full-sibling-based trios together (subgroup 10) produced an a 2 estimate of 0.53 (95% CI 0.43–0.62). The estimate from the half-sibling-based trios (subgroup 11) was similar (0.59, 95% CI 0.43–0.76) as were the results when we combined the two groups of trios (subgroup 12): 0.53 (95% CI 0.46–0.61). We obtained an a 2 estimate from twins of 0.43 (95% CI 0.14–0.72).

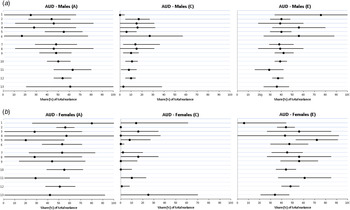

Fig. 3. (a) Parameter estimates for additive genetic effects (A), shared environmental effects (C) and unique environmental effects (E) estimates from various kinds of sibling trios for alcohol use disorder (AUD) in males. The numbers given at the left side of the figure correspond to the model number outlined in Table 2. (b) Parameter estimates for additive genetic effects (A), shared environmental effects (C) and unique environmental effects (E) estimates from various kinds of sibling trios for AUD in females. The numbers given at the left side of the figure correspond to the model number outlined in Table 2. Values are estimates, with 95% confidence intervals represented by horizontal bars.

AUD

Detailed results are summarized in Fig. 3a and b , and key findings are summarized in Table 5. AUD and DA are quite a bit rarer than CB so estimates are known less precisely. In males, heritability estimates for AUD in full-sibling-based trios (0.50, 95% CI 0.40–0.61) were slightly lower than those obtained from half-sibling-based trios (0.63, 95% CI 0.46–0.80) and produced an aggregate estimate of 0.54 (95% CI 0.46–0.62). This was slightly lower than that obtained from twins (0.61, 95% CI 0.21–1.00).

In females, heritability estimates for full-sibling-based trios (0.55, 95% CI 0.39–0.72) were much higher than those obtained from half-sibling-based trios which were known very imprecisely (0.25, 95% CI 0.00–0.56). Joint estimates from both groups of trios (0.51, 95% CI 0.38–0.65) were slightly higher than those obtained from twins (0.42, 95% CI 0.00–0.92).

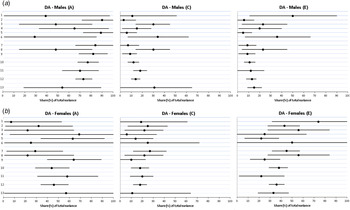

DA

Detailed results are summarized in Fig. 4a and b , and key findings are summarized in Table 5. In males, heritability estimates for full-siblings-based trios (0.77, 95% CI 0.68–0.87) were slightly higher than those obtained from the half-sibling-based trios (0.70, 95% CI 0.54–0.87) and produced the following aggregate estimate: 0.73 (95% CI 0.66–0.81). This was substantially higher than that obtained from twins but this estimate was known quite imprecisely (0.54, 95% CI 0.19–0.89).

Fig. 4. (a) Parameter estimates for additive genetic effects (A), shared environmental effects (C) and unique environmental effects (E) estimates from various kinds of sibling trios for drug abuse (DA) in males. The numbers given at the left side of the figure correspond to the model number outlined in Table 2. (b) Parameter estimates for additive genetic effects (A), shared environmental effects (C) and unique environmental effects (E) estimates from various kinds of sibling trios for DA in females. The numbers given at the left side of the figure correspond to the model number outlined in Table 2. Values are estimates, with 95% confidence intervals represented by horizontal bars.

In females, heritability estimates for full-sibling-based trios (0.44, 95% CI 0.29–0.60) were modestly lower than those obtained from the half-sibling-based trios (0.58, 95% CI 0.31–0.86). Aggregate heritability estimates from the two samples equaled 0.46 (95% CI 0.34–0.59), which was somewhat lower than that found in the twins (0.57, 95% CI 0.00–1.00), although CIs were very large.

Relationship of heritability estimates from sibling trios and twins

An additional way to determine if twin studies might have systematic biases in their heritability estimate is to compare all individual estimates with our sibling trios and compare them in aggregate with those found in the twins. We had a total of 54 heritability estimates from sibling trios: 3 syndromes x 9 sets of trios x 2 sexes. When we compared these trio-based estimates with those obtained from twins, heritability estimates from the siblings were lower, tied and higher than those from twins in 26, one and 27 comparisons, respectively.

Shared environment

As seen in Fig. 2a and b , and Table 5, for CB, aggregate c 2 estimates from both the full- and half-sib-based trios were lower than that found for twins both for males [0.14 (95% CI 0.11–0.16) v. 0.23 (95% CI 0.07–0.39)] and females [0.05 (95% CI 0.01–0.09) v. 0.21 (95% CI 0.00–0.47)]. For AUD (Fig. 3a and b , and Table 5), shared environmental estimates were higher from all the sibling trio data than from the twins in males [0.15 (95% CI 0.05–0.14) v. 0.03 (95% CI 0.00–0.38)] and lower in females [0.01 (95% CI 0.00–0.08) v. 0.25 (95% CI 0.00–0.70)]. As seen in Fig. 4a and b , and Table 5, for DA, c 2 estimates from both the full- and half-sib-based trios were lower than that found from twins for males [0.14 (95% CI 0.10–0.18) v. 0.31 (95% CI 0.00–0.65)] but higher in females [0.18 (95% CI 0.12–0.24) v. 0.11 (95% CI 0.00–0.64)]. Of our 54 c 2 estimates from all the types of sibling trios examined, 33 were lower than those found in twins, one was tied and 20 were higher.

Discussion

This paper had three major aims. First, we sought to introduce a novel design for the estimation of genetic and environmental sources of familial resemblance using common sibling relationships. Our ability to identify such pairs and determine their childhood cohabitation history opens up new ways to address old questions. Like twin studies, these sibling-based methods address sources of within-generation familial resemblance. This design is also novel in its focus on informative sibling trios which reflect independent natural experiments because they contain two different kinds of sibling relationships. This approach thereby controls for family-level differences. We study genetic effects by examining siblings who share approximately 50% of their genes (full-sibs), 25% of their genes (half-sibs) and 0% of their genes (step-sibs). We study shared environmental effects as indexed by their years of living together while growing up.

In the Swedish population born from 1960 to 1990, we identified 158 135 unique probands for these informative same-sex trios compared with 10 241 MZ and DZ same-sex twin pairs with known zygosity. Current human populations contain many non-twin sibling trios who can provide information about the source of familial resemblance.

Our second aim was to evaluate the reliability of the estimates of genetic and shared environmental effects obtained from the wide array of sibling trios we examined. Significant disagreement in estimates across trio types would suggest that factors other than those included in our model are making an impact on familial resemblance. For all three of our independent model-fitting exercises (within our six types of full-sibling-based trios, three types of half-sibling-based trios, and between our full- and half-sibling aggregate estimates), our joint estimates had identical or superior fits on two or more of the three fit indices, suggesting that the estimates were generally statistically homogeneous.

Our third aim was to evaluate whether, as postulated by critics (Jackson, Reference Jackson and Jackson1960; Lewontin et al. Reference Lewontin, Rose and Kamin1985; Pam et al. Reference Pam, Kemker, Ross and Golden1996; Joseph, Reference Joseph2002), twin studies systematically overestimate heritability. Here our results were clear. The heritability estimates for CB, AUD and DA that we obtained from our sibling trios were very similar to those obtained from MZ and DZ twins from the same population using the same diagnostic methods. These results are consistent with two previous analyses of CB in full- and half-sibling pairs from Sweden using typical modeling approaches (rather than informative trios) which closely approximated results obtained from twins (Frisell et al. Reference Frisell, Pawitan, Långström and Lichtenstein2012; Kendler et al. Reference Kendler, Lonn, Maes, Sundquist and Sundquist2015a ).

Of the many methodological concerns about classical twin studies, two have been most prominent: the equal environment assumption (EEA) and the generalizability problem (Kendler et al. Reference Kendler, Neale, Kessler, Heath and Eaves1994; LaBuda et al. Reference LaBuda, Svikis and Pickens1997). Twin studies critically rely on the assumption that the trait-relevant environmental similarity of MZ and DZ twins are the same. If the environments of MZ twins are appreciably more similar than DZ twins, that could result in upward biases on the estimation of heritability. While the EEA has been tested many times and typically supported (Kendler, Reference Kendler1983; Kendler & Prescott, Reference Kendler and Prescott2006; Barnes et al. Reference Barnes, Wright, Boutwell, Schwartz, Connolly, Nedelec and Beaver2014; LoParo & Waldman, Reference LoParo and Waldman2014), it has a psychological plausibility because MZ twins are a unique human relationship – effectively genetic clones who typically look identical and have similar personalities.

Our approach, by contrast, utilizes a diversity of relationships to obtain estimates of genetic effects. These include full- and half-siblings reared apart whose resemblance provides direct estimates for heritability. Comparing full- and half-siblings reared together for differing lengths of time or full- and half-sibs with step-sibs permits estimation of a 2 more indirectly.

The generalizability problem arises from the unique developmental processes involved in twins that are not shared by singletons. Twins have higher rates of obstetric complications and congenital malformations, and lower birth weights (Bryan, Reference Bryan1992; Bush & Pernoll, Reference Bush, Pernoll, Decherney, Nathan, Goodwin and Laufer2007). Twins always share the same intra-uterine environment, are the same age, and are typically emotionally closer than regular siblings (Bakker, Reference Bakker1987; Rutter & Redshaw, Reference Rutter and Redshaw1991; LaBuda et al. Reference LaBuda, Svikis and Pickens1997). Why, this argument goes, should we assume that results from twins should extrapolate to other more common familial relationships? Unlike twin studies, our sibling trios derive estimates from the most common of human sibling relationships that do not share any of these special features of twins.

While critics have charged that twin studies overestimate genetic effects, more plausible claims that twin studies might find stronger shared environmental effects than would be seen for more typical siblings have been less prominent. Not only do twins share the same womb at the same time, but, always being the same age, are more likely to share family, school and especially peer group experiences more than non-twin siblings. This is likely of particular relevance for externalizing and substance use disorders, where contact with deviant peers is likely of particular etiologic importance (Hawkins et al. Reference Hawkins, Herrenkohl, Farrington, Brewer, Catalano, Harachi, Loeber and Farrington1998; Petraitis et al. Reference Petraitis, Flay, Miller, Torpy and Greiner1998; Allen et al. Reference Allen, Donohue, Griffin, Ryan and Turner2003; Kendler et al. Reference Kendler, Ohlsson, Mezuk, Sundquist and Sundquist2015b ). Indeed, as predicted from peer and school group effects, full-siblings in Sweden closer in age are more highly correlated both for DA (Kendler et al. Reference Kendler, Ohlsson, Sundquist and Sundquist2013) and CB (Kendler et al. Reference Kendler, Morris, Lönn, Sundquist and Sundquist2014). Our results provide evidence that shared environmental effects estimated in twin studies may be greater than that found for more typical siblings.

Limitations

These results should be interpreted in the context of four potential methodological limitations. First, we only studied three syndromes and may not obtain similar results with other traits or disorders. Second, we did not examine opposite-sex pairs. Including them would increase substantially the number of informative sibling trios but would increase considerably the complexity of the modeling. Third, our analyses could have been affected by contact between reared-apart siblings. We compared estimates for our standard trios containing full-sibs reared together and half-sibs reared apart, and then eliminated trios where the half-siblings lived in the same municipality. Estimates changed only modestly. Fourth, the validity of our assumption that shared environment is a linear function of the number of years of cohabitation in childhood can be questioned. We examined resemblance in full-sibling pairs for CB, AUD and DA as a function of years residing together. The increase in resemblance was stronger between zero and 6 years than between 7 and 13 years. We therefore fitted a different weighting for years of cohabitation that reflects this non-linearity. The differences in parameter estimates from the original and new weightings were quite small.

Conclusions

We propose and then apply to DA, AUD and CB a novel design to estimate genetic and environmental effects from full-, step- and half-siblings. Unlike prior modeling approaches which utilize all available informative relative pairs for a particular relationship, we examined only informative sibling trios, thereby controlling for familial background effects. For all three externalizing syndromes, heritability estimates obtained from this method closely approximated those found from twins, providing strong evidence to counter extensive prior concerns that twin studies overestimate heritability. Because psychiatric genetics is an observational and not an experimental science, there is no such thing as a definitive study. All studies have methodological limitations. Therefore, one important approach to evaluate the validity of our findings is to study the same question using disparate methods. If, as is the case here, diverse methods, with different potential methodological limitations, yield similar results, we can be increasingly confident of the broad accuracy of our findings. Our results suggest that, first, overestimation of heritability by twin studies is unlikely to be contributing substantially to the missing heritability problem and, second, shared environmental influences are probably somewhat stronger in twin studies than in other sibling designs.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S003329171500224X

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by grants DA030005 and AA0235341 from the US National Institutes of Health, the Ellison Medical Foundation, the Swedish Research Council to K.S. (2014-2517), the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare (in Swedish: FORTE; Reg. no. 2013-1836) to K.S., and FORTE (Reg. no. 2014-0804) and the Swedish Research Council to J.S. (2012-2378 and 2014-10134) as well as ALF funding from Region Skåne awarded to J.S. and K.S.

Declaration of Interest

None.