Introduction

Despite efforts to characterize posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) pathophysiology, neurobiological markers to aid in diagnosis and treatment development are yet to be agreed upon. In an attempt to establish such markers, extant research has employed Pavlovian fear conditioning paradigms, specifically differential cue-conditioning paradigms (Rauch et al., Reference Rauch, Shin and Phelps2006; Liberzon and Sripada, Reference Liberzon and Sripada2008; Shvil et al., Reference Shvil, Rusch, Sullivan and Neria2013; Maren and Holmes, Reference Maren and Holmes2016), which in humans typically include a conditioning phase, where an association between a neutral stimulus (i.e. picture) and an aversive stimulus (unconditioned stimulus, US; i.e. electric shock) is formed (CS+) while a second neutral stimulus is presented without the US (CS−). This association is often followed by an extinction learning phase, where the CS+ is presented without the US until the expression of the response diminishes. In some cases, after some time has elapsed, the return of fear is assessed in a subsequent extinction recall phase.

Neurobiological research has shown that during differential cue-conditioning the association learning between a single CS (e.g. tone), and US (e.g. electric shock), is associated with increased amygdala activation in both animals (Blanchard and Blanchard, Reference Blanchard and Blanchard1972; Kalin et al., Reference Kalin, Shelton and Davidson2004; Chudasama et al., Reference Chudasama, Izquierdo and Murray2009) and humans (Bechara et al., Reference Bechara, Tranel, Damasio and Adolphs1995; LaBar et al., Reference LaBar, LeDoux, Spencer and Phelps1995; Alvarez et al., Reference Alvarez, Biggs, Chen, Pine and Grillon2008; Britton et al., Reference Britton, Lissek, Grillon, Norcross and Pine2011). However, other differential cue-conditioning studies in humans found null amygdala results (Sehlmeyer et al., Reference Sehlmeyer, Schöning, Zwitserlood, Pfleiderer, Kircher, Arolt and Konrad2009). In an attempt to clarify the neural signatures of differential cue-conditioning in humans, several meta-analyses have been performed (Etkin and Wager, Reference Etkin and Wager2007; Mechias et al., Reference Mechias, Etkin and Kalisch2010; Fullana et al., Reference Fullana, Harrison, Soriano-Mas, Vervliet, Cardoner, Àvila-Parcet and Radua2016), with findings implicating additional brain regions. When comparing brain activation to a CS+ v. CS− during conditioning, dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC) and anterior insular cortex (AIC) were found to be most consistently activated (Etkin and Wager, Reference Etkin and Wager2007; Mechias et al., Reference Mechias, Etkin and Kalisch2010; Fullana et al., Reference Fullana, Harrison, Soriano-Mas, Vervliet, Cardoner, Àvila-Parcet and Radua2016). Conversely, activation in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) and anterior hippocampus has been characterized as more responsive to CS− v. CS+, suggesting a role in safety – as opposed to threat – signal processing (Fullana et al., Reference Fullana, Harrison, Soriano-Mas, Vervliet, Cardoner, Àvila-Parcet and Radua2016; Harrison et al., Reference Harrison, Fullana, Via, Soriano-Mas, Vervliet, Martínez-Zalacaín, Pujol, Davey, Kircher, Straube and Cardoner2017). Subsequent meta-analyses for the related processes of extinction learning and extinction recall confirmed higher activation in the mPFC/vmPFC during extinction learning (Diekhof et al., Reference Diekhof, Geier, Falkai and Gruber2011; Fullana et al., Reference Fullana, Albajes-Eizagirre, Soriano-Mas, Vervliet, Cardoner, Benet, Radua and Harrison2018) and extinction recall (Diekhof et al., Reference Diekhof, Geier, Falkai and Gruber2011), which is interpreted as reflecting inhibitory processing within the ‘extended fear network’(Gottfried and Dolan, Reference Gottfried and Dolan2004; Delgado et al., Reference Delgado, Nearing, LeDoux and Phelps2008). Furthermore, insular cortex and dACC was also found activated during extinction learning and extinction recall (Fullana et al., Reference Fullana, Albajes-Eizagirre, Soriano-Mas, Vervliet, Cardoner, Benet, Radua and Harrison2018). Taken together, the dorsal and ventral medial prefrontal, including anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) subregions, insula, hippocampus, and amygdala have all been suggested as key components of a network responsible for learning and remembering emotion-stimulus associations (emotional learning) during conditioning in healthy adults.

Patients with PTSD are characterized by persistent and exaggerated threat responses, even in the presence of safety cues (Shvil et al., Reference Shvil, Rusch, Sullivan and Neria2013). However, it is debated whether such threat responses are due to emotional enhancement during conditioning, impaired extinction/inhibitory control (i.e. an inability to modulate emotional expression), or both. Functional MRI studies in PTSD have reported reduced mPFC, ACC, amygdala, and hippocampus activation during conditioning and extinction learning (Rauch et al., Reference Rauch, Shin and Phelps2006; Liberzon and Sripada, Reference Liberzon and Sripada2008; Shin et al., Reference Shin, Lasko, Macklin, Karpf, Milad, Orr, Goetz, Fischman, Rauch and Pitman2009; Shvil et al., Reference Shvil, Rusch, Sullivan and Neria2013; Reznikov et al., Reference Reznikov, Binko, Nobrega and Hamani2016; Wicking et al., Reference Wicking, Steiger, Nees, Diener, Grimm, Ruttorf, Schad, Winkelmann, Wirtz and Flor2016). Furthermore, a meta-analysis focusing on emotional processing, including differential cue-conditioning paradigms, reported that patients with PTSD showed amygdala, vmPFC, dmPFC, ACC, and anterior hippocampus hypoactivation when compared to patient-comparison subjects, during a variety of emotional processing tasks (Etkin and Wager, Reference Etkin and Wager2007). However, fMRI differential cue-conditioning studies in PTSD have yielded more mixed results. During conditioning, some have reported reduced amygdala activation (Diener et al., Reference Diener, Nees, Wessa, Wirtz, Frommberger, Penga, Ruttorf, Ruf, Schmahl and Flor2016), whereas others reported no alterations in amygdala activation (Milad et al., Reference Milad, Pitman, Ellis, Gold, Shin, Lasko, Zeidan, Handwerger, Orr and Rauch2009; Garfinkel et al., Reference Garfinkel, Abelson, King, Sripada, Wang, Gaines and Liberzon2014; Shvil et al., Reference Shvil, Sullivan, Schafer, Markowitz, Campeas, Wager, Milad and Neria2014). Still, a PET scan study did show increased amygdala activity in PTSD (Bremner et al., Reference Bremner, Vermetten, Schmahl, Vaccarino, Vythilingam, Afzal, Grillon and Charney2005). Moreover, increased amygdala activation during extinction learning (Milad et al., Reference Milad, Pitman, Ellis, Gold, Shin, Lasko, Zeidan, Handwerger, Orr and Rauch2009) and extinction recall (Garfinkel et al., Reference Garfinkel, Abelson, King, Sripada, Wang, Gaines and Liberzon2014) in PTSD have also been reported in some but not all fMRI studies (Shvil et al., Reference Shvil, Sullivan, Schafer, Markowitz, Campeas, Wager, Milad and Neria2014). Results are also mixed for other regions: heightened dACC activation during extinction recall has been reported in some studies (Milad et al., Reference Milad, Pitman, Ellis, Gold, Shin, Lasko, Zeidan, Handwerger, Orr and Rauch2009; Shvil et al., Reference Shvil, Sullivan, Schafer, Markowitz, Campeas, Wager, Milad and Neria2014), whereas others have implicated middle cingulate alterations (Garfinkel et al., Reference Garfinkel, Abelson, King, Sripada, Wang, Gaines and Liberzon2014). Finally, although lower vmPFC and hippocampus activation were found during extinction recall in patients with PTSD (Milad et al., Reference Milad, Pitman, Ellis, Gold, Shin, Lasko, Zeidan, Handwerger, Orr and Rauch2009), this finding was not replicated in a subsequent study (Shvil et al., Reference Shvil, Sullivan, Schafer, Markowitz, Campeas, Wager, Milad and Neria2014).

To provide a description of the neural signatures of experimental phases (conditioning, extinction learning, and extinction recall) in PTSD, and examine the differences compared with trauma-exposed healthy controls (TEHC), we conducted three separate meta-analyses of fMRI fear processing studies, focusing on conditioning, extinction learning, and extinction recall processes. We only included PTSD v. TEHC comparisons to determine the neural signatures of PTSD psychopathology rather than trauma-exposure per-se. We only included PTSD v. TEHC comparisons to determine the neural signatures of PTSD psychopathology rather than trauma-exposure per-se, as trauma-exposure does not always lead to PTSD. Trauma-history is important in elucidating differences between exposure to trauma per se and PTSD. Additionally, we did not include non-trauma exposed healthy controls as a comparison group as most previous fMRI studies examining this population rarely assessed trauma history, therefore overlap between trauma-exposed and trauma-naïve participants may exist, and therefore we preferred to exclude such studies to avoid any confound of potential trauma-naïve participants. Following recent suggestions for conducting neuroimaging meta-analyses (Müller et al., Reference Müller, Cieslik, Laird, Fox, Radua, Mataix-Cols, Tench, Yarkoni, Nichols, Turkeltaub, Wager and Eickhoff2018), we included published and unpublished studies datasets and, where feasible, we included original statistical brain maps. Moreover, we conducted additional robustness analyses of the primary results to appropriately evaluate the reliability of the results.

Methods and materials

Protocol details for this meta-analysis were registered on PROSPERO and can be accessed at https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42017057844

Literature search and study selection

A comprehensive literature search using PubMed, Web of Knowledge, and Scopus was conducted for English-language peer-reviewed studies of threat (or fear) learning (conditioning, extinction learning, or extinction recall) in human adults (age>18 years) with PTSD or trauma exposure published between January 1998 and September 2018 (online Supplementary Fig. S1; For a list of the ten full-articles reviewed excluded and reasoning see online Supplementary Table S1) paper The search terms were: ‘fMRI,' magnetic resonance imaging,' ‘aversive,' ‘threat,' ‘fear,' ‘Pavlovian,' conditioning,' ‘extinction,' ‘Posttraumatic stress disorder,' PTSD,' and their combinations. Returned articles were inspected for additional studies. Researchers in the field were contacted about the potential inclusion of unpublished data. For studies containing participant group overlap, the most recent study was included. Corresponding authors were contacted and asked to share statistical brain maps or provide whole-brain analysis peak results if these maps were not available. For this purpose, we contacted eight researchers in the field; received a response from six researchers; and received statistical brain maps from five researchers.

We included studies using a differential cue-conditioning paradigm, reporting direct CS+ and CS− comparisons (during conditioning and extinction learning) and between an extinguished (CS + E) v. unextinguished (CS + NE) or CS + E and CS− (during extinction recall) between patients with PTSD and TEHCs. Studies were excluded if they used masked CSs or a US with ambiguous meaning; if the CS-US contingencies changed during conditioning; or if the US was not delivered following the CS+ during conditioning (e.g. trace conditioning). We also excluded studies from which peak information or statistical brain maps could not be retrieved or did not report whole-brain statistical results. Statistical brain maps took the form of un-thresholded Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM) or Analysis of Functional NeuroImages (AFNI) t contrast images. We obtained statistical brain maps of the primary contrast of interest from five independent studies, including unpublished results from a current co-author YN (Morey et al., Reference Morey, Dunsmoor, Haswell, Brown, Vora, Weiner, Stjepanovic, Wagner and LaBar2015; Diener et al., Reference Diener, Nees, Wessa, Wirtz, Frommberger, Penga, Ruttorf, Ruf, Schmahl and Flor2016; Kaczkurkin et al., Reference Kaczkurkin, Burton, Chazin, Manbeck, Espensen-Sturges, Cooper, Sponheim and Lissek2016; Wicking et al., Reference Wicking, Steiger, Nees, Diener, Grimm, Ruttorf, Schad, Winkelmann, Wirtz and Flor2016). For the remaining studies (Milad et al., Reference Milad, Pitman, Ellis, Gold, Shin, Lasko, Zeidan, Handwerger, Orr and Rauch2009; Garfinkel et al., Reference Garfinkel, Abelson, King, Sripada, Wang, Gaines and Liberzon2014), peak regional coordinates and statistics were extracted and coded from the original publications. The inclusion of original maps is a distinguishing feature of the seed-based d mapping (SDM) approach compared to other meta-analytic tools based solely on the inclusion of peak co-ordinate information (Radua et al., Reference Radua, Mataix-Cols, Phillips, El-Hage, Kronhaus, Cardoner and Surguladze2012). The literature search, decisions on inclusion, and data extraction were all performed independently by two authors (BSJ and MF). Our final analyses included 156 patients with PTSD and 148 TEHCs from seven different studies. For each study, key demographic variables were extracted (Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of the studies included in the three meta-analyses

PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; TEHC, trauma-exposed healthy controls; NI, not included; NR, not reported. CS, conditioned stimulus; ITI, inter-trial interval; CS+, CS followed by unconditioned stimulus; CS−, CS not followed by unconditioned stimulus; CS + E, CS + which was extinguished during extinction learning; CS + NE, CS + to not be extinguished during extinction learning; US, unconditioned stimulus; SCR, skin conductance response.

Table illustrates the characteristics of each study included in the meta-analysis per the three experimental phases (conditioning, extinction learning, and extinction recall).

Conditioning studies

For conditioning, when more than one contrast was available (e.g. early and late conditioning), we opted to include the contrast involving all trials. If this contrast was not available, we focused on early conditioning trials (the first half of the trials presented in an experiment) since activation in some regions may be more pronounced during early conditioning phases (Sehlmeyer et al., Reference Sehlmeyer, Schöning, Zwitserlood, Pfleiderer, Kircher, Arolt and Konrad2009; Fullana et al., Reference Fullana, Harrison, Soriano-Mas, Vervliet, Cardoner, Àvila-Parcet and Radua2016). Seven studies were included, with five providing statistical brain maps. All studies had a pre-conditioning (i.e. familiarization) phase, used images as CS and either an electric shock or trauma-related pictures as US (Table 1).

Extinction learning studies

For extinction learning, when more than one contrast was available, we focused on late extinction learning trials (the second half of the trials) since early trials may reflect the persistence of conditioning rather than extinction learning (Milad et al., Reference Milad, Wright, Orr, Pitman, Quirk and Rauch2007). Five studies were included, with three providing statistical brain maps (Table 1).

Extinction recall studies

Four studies (two statistical brain maps) were included in the extinction recall meta-analysis (Table 1). We used early extinction recall phases (the first half of the trials) as late trials are considered to involve re-extinction processes (Lonsdorf et al., Reference Lonsdorf, Menz, Andreatta, Fullana, Golkar, Haaker, Heitland, Hermann, Kuhn, Kruse, Meir Drexler, Meulders, Nees, Pittig, Richter, Römer, Shiban, Schmitz, Straube, Vervliet, Wendt, Baas and Merz2017). In three studies, extinction recall was assessed in the same context and one day after extinction learning. In the fourth,21 extinction recall was assessed in a novel context 1 week later.

Meta-analytic approach

Our primary focus was on CS+ > CS− comparison (conditioning; extinction learning) and CS + E > CS + NE trials or CS + E > CS− (extinction recall) in PTSD v. TEHC. The anisotropic effect-size version of seed-based d mapping software (AES-SDM software, version 5.141; https://www.sdmproject.com; Radua et al., Reference Radua, Mataix-Cols, Phillips, El-Hage, Kronhaus, Cardoner and Surguladze2012, Reference Radua, Rubia, Canales-Rodríguez, Pomarol-Clotet, Fusar-Poli and Mataix-Cols2014) was used to generate voxel-wise hyper/hypoactivation effect size maps corresponding to the analyses and contrasts of interest. AES-SDM is a neuroimaging meta-analytic approach capable of combining tabulated brain hyper/hypoactivation results (i.e. regional peak statistic and coordinate information) with actual hyperactivation and hypoactivation empirical voxel-wise brain maps (e.g. SPM, AFNI) and which improves upon the positive features of existing peak probability methods for meta-analysis, such as Activation Likelihood Estimation (ALE; Eickhoff et al., Reference Eickhoff, Laird, Grefkes, Wang, Zilles and Fox2009; Laird et al., Reference Laird, Eickhoff, Kurth, Fox, Uecker, Turner, Robinson, Lancaster and Fox2009) or Multilevel Kernel Density Analysis (MKDA; Wager et al., Reference Wager, Lindquist and Kaplan2007, Reference Wager, Lindquist, Nichols, Kober and Van Snellenberg2009). This method, which has been validated and used in several structural and functional fMRI studies, first creates a brain map of the effect size of the difference between the two groups (patients with PTSD and TEHC) in the BOLD response to CS+ (v. CS−) for each study (either from SPMs or from peak information). Afterward, it conducts a voxel-wise standard random-effects meta-analysis (weighting the studies for sample size, variance, and between-study heterogeneity). The method comprised three major steps. Firstly, whole brain maps of the effect size of the difference between the two groups (PTSD > TEHC and TEHC > PTSD in the same map) were recreated separately for each study, either from statistical brain maps or the reported peak regional coordinate statistics. Secondly, these individual maps were meta-analyzed using random-effects techniques of standard meta-analyses; these models were independently fitted in each voxel, but the statistical significance was derived from a whole-brain permutation test. We used ES-SDM default thresholds (voxel-level p < 0.005 uncorrected, minimum cluster extent ten contiguous voxels, peak SDM-Z > 1.00), as previous simulations indicate they provide an optimal balance between sensitivity and false-positive rate (Radua et al., Reference Radua, Rubia, Canales-Rodríguez, Pomarol-Clotet, Fusar-Poli and Mataix-Cols2014; Fullana et al., Reference Fullana, Harrison, Soriano-Mas, Vervliet, Cardoner, Àvila-Parcet and Radua2016). All areas were identified using the peak activation of the cluster using the Automated Anatomical Labeling Atlas (AAL; Maldjian et al., Reference Maldjian, Laurienti, Kraft and Burdette2003, Reference Maldjian, Laurienti and Burdette2004). Thirdly, standard complementary analyses were conducted to assess the robustness of the main findings, therefore properly evaluating and validating the results of the main findings. This analysis included jackknife sensitivity (to check for replicability), I 2 index, Cochran's Q, and Egger's test (Egger et al., Reference Egger, Davey Smith, Schneider and Minder1997) calculations to assess the heterogeneity of effect sizes and publication biases, respectively. We report both the p values and a description of the tests (I 2 values and the visual inspection of funnel plots), because p values alone may have a limited sensitivity when the meta-analysis includes few studies. We conducted robustness analyses for the brain areas of interest discussed in the text, mainly the medial frontal cortices, hippocampus, amygdala, and insula. Finally, we should note that when PTSD hyper-activate, the effect is PTSD > TEHC, but when they fail to deactivate, the effect is also PTSD > TEHC. For example, if TEHC has activation of ‘1’ and PTSD has activation of ‘2’, the latter hyper-activate and PTSD > TEHC (2 > 1). Similarly, if TEHC deactivates ‘–1’ and PTSD do not respond, the latter fails to deactivate and PTSD > TEHC (0 > –1). To establish the results directionality (e.g. to know whether PTSD > TEHC means that PTSD hyper-activate or fail to deactivate), we meta-analyzed the within-group contrasts (CS+ > CS− and CS− > CS+ per group) for those studies where group or individual subject maps were available (Table 2; online Supplementary Methods).

Table 2. Studies included in the directionality meta-analyses phases

Table illustrating the studies included in each phase of the directionality analysis of the meta-analysis.

Results

Conditioning

Patients with PTSD, compared to TEHCs, demonstrated greater activation of the medial prefrontal cortex including orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), subgenual ACC (sgACC), and vmPFC, posterior insula and superior temporal gyrus, posterior hippocampus, and anterior hippocampus extending to the amygdala during conditioning (Fig. 1; Peak information in online Supplementary Table S1). To disentangle results directionality, we ran separate analyses for each group (online Supplementary Methods), which further elucidated that the PTSD group was characterized by sgACC, insula, and amygdala hyperactivation during the CS+ presentation. Furthermore, there was OFC and vmPFC hypoactivation during CS− presentation (online Supplementary Fig. S2). The reverse contrast revealed greater ventrolateral prefrontal cortex and the anterior thalamus activation in TEHC compared to PTSD (Fig. 1; Peak information in online Supplementary Table S2), which were driven by a failure to activate these areas in the PTSD group during the CS+ presentation (online Supplementary Fig. S2). Robustness analyses showed an overall results replicability, and no heterogeneity or publication bias evidence (all results were found in more than 3/6 jack-knife folds; all I 2 < 13% with all Q p > 0.32; and all funnel plots were symmetric with all Egger p > 0.12; online Supplementary Table S2).

Fig. 1. Brain regions with consistently significantly higher brain functional activation in PTSD compared to TEHC (red) and TEHC compared to PTSD (green) for CS+ > CS− contrast during conditioning. Results are displayed at p < 0.005 (Cluster size ⩾10 voxels) on the MNI 152 T1 0.05mm template. AMG, amygdala; HIP, Hippocampus; OFC, Orbitofrontal Cortex; sgACC, subgenual Anterior Cingulate Cortex; STG, Superior Temporal Gyrus; THA, Thalamus; vmPFC, ventromedial Prefrontal Cortex.

Extinction learning

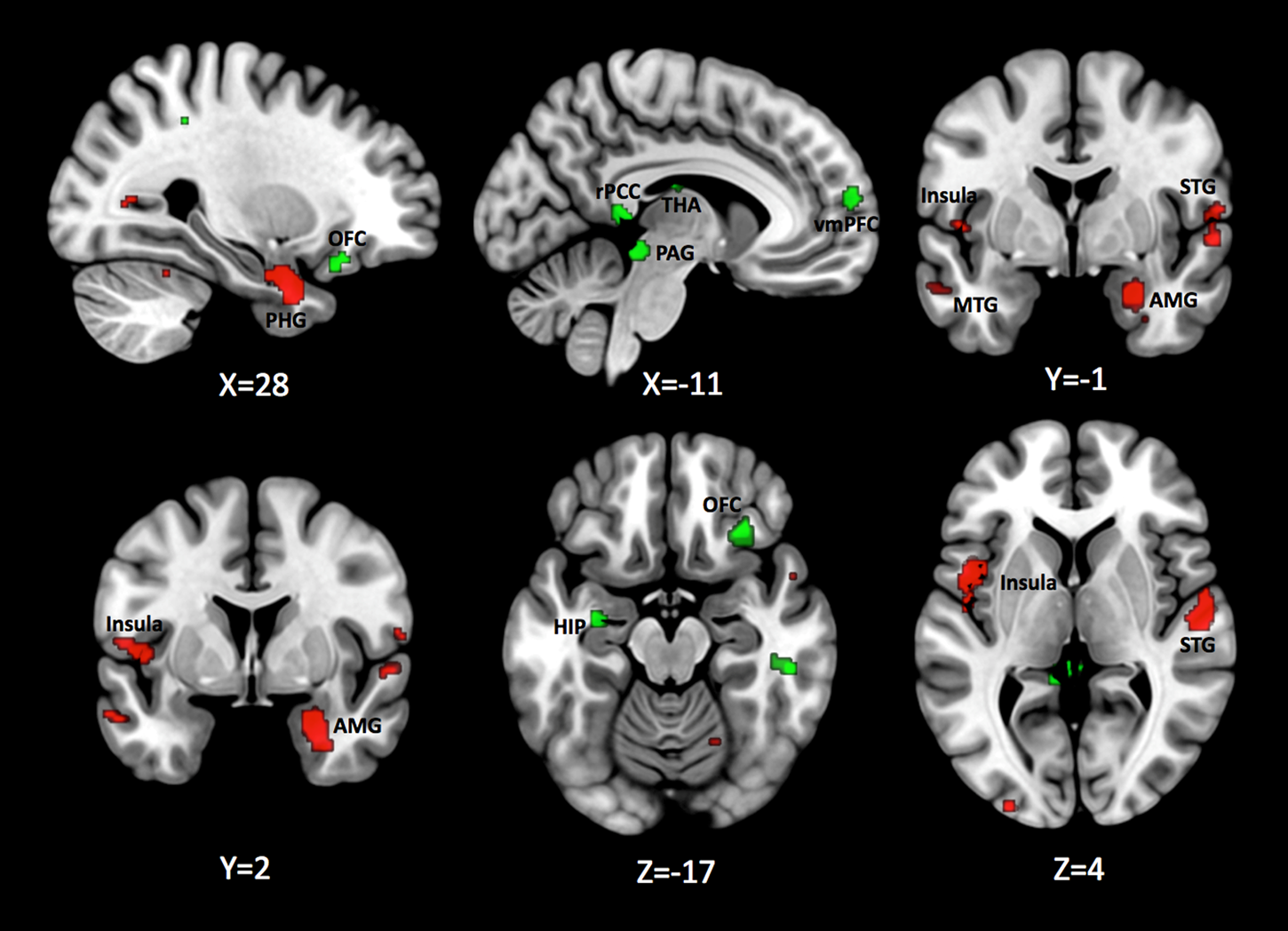

Patients with PTSD, compared to TEHCs, demonstrated greater parahippocampal gyrus activation extending to amygdala and anterior hippocampus, middle occipital cortex, as well as bilateral mid-posterior insular cortex activation during extinction learning (Fig. 2; Peak information in online Supplementary Table S3). Directionality analyses confirmed differences observed in the amygdala, parahippocampal gyrus, and insular cortex were driven by a failure to deactivate these regions in the PTSD group during CS+ presentation (online Supplementary Fig. S3). The opposite contrast (TEHC>PTSD) identified greater inferior parietal cortex, posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), inferior temporal gyrus, thalamus, periaqueductal gray, vmPFC, and OFC, and anterior hippocampus activation (Fig. 2; Peak information in online Supplementary Table S3). Directionality analyses confirmed a failure to activate the PCC, vmPFC, OFC, and hippocampus and a periaqueductal gray hypoactivation in the PTSD group during the CS+ presentation (online Supplementary Fig. S3). Robustness analyses showed that these results were overall replicable and there was no heterogeneity evidence (all results were found in more than 3/5 jack-knife folds; all I 2 < 0% with all Q p > 0.43; and all funnel plots were symmetric with all Egger p > 0.07). Although the Egger test p value was significant for the insula, indicating publication bias, funnel plots showed that asymmetry was in the opposite direction to that expected if there was publication bias, suggesting the result was not driven by a particular study (online Supplementary Table S3).

Fig. 2. Brain regions with consistently significantly higher brain functional activation in PTSD compared to TEHC (red) and TEHC compared to PTSD (green) for CS+ > CS− contrast during extinction learning. Results are displayed at p < 0.005 (Cluster size ⩾ 10 voxels) on the MNI 152 T1 0.05mm template. AMG, Amygdala; HIP, Hippocampus; MTG, Middle Temporal Gyrus; OFC, Orbitofrontal Cortex; PAG, Periaqueductal gray; PHG, Parahippocampal Gyrus; rPCC, retrosplenial Posterior Cingulate Cortex; STG, Superior Temporal Gyrus; THA, Thalamus; vmPFC, ventromedial Prefrontal Cortex.

Extinction recall

Patients with PTSD, compared to TEHCs, showed greater amygdala activation extending to the anterior hippocampus, dorsal ACC, vmPFC, and OFC during extinction recall (Fig. 3; Peak information in online Supplementary Table S4). Directionality analyses demonstrated higher OFC and amygdala activation was led by a failure to deactivate these areas in the PTSD group during the CS+ presentation (online Supplementary Fig. S4). The opposite contrast (TEHC > PTSD), revealed greater posterior thalamus activation (Fig. 3; Peak information in online Supplementary Table S4), which was led by a failure to activate in the PTSD group during CS+ presentation (online Supplementary Fig. S4). Robustness analyses showed that these results were replicable, with no evidence of heterogeneity or publication bias in any of them (all results were found in more than 2/4 jack-knife folds; all I 2 < 2% with all Q p > 0.37; and all funnel plots were symmetric with all Egger p > 0.35; online Supplementary Table S4).

Fig. 3. Brain regions with consistently significantly higher brain functional activation in PTSD compared to TEHC (red) and TEHC compared to PTSD (green) for CS+ > CS− contrast during extinction recall. Results are displayed at p < 0.005 (Cluster size ⩾ 10 voxels) on the MNI 152 T1 0.05mm template. AMG, Amygdala; ACC, Anterior Cingulate Cortex; OFC, Orbitofrontal Cortex; THA, Thalamus.

Discussion

The present meta-analysis aimed to provide a description of the neural signatures of fear processing in PTSD. Our findings indicate that patients with PTSD show increased activation in areas such as the amygdala, insula, and ACC during conditioning, extinction learning, and extinction recall. In conjunction, our data show higher activation in areas such as the hippocampus and mPFC hypoactivation. Particularly, our data showed lower vmPFC activation during extinction learning. Finally, an overall lack of thalamus activation during all phases was found for patients with PTSD compared to TEHCs.

Overall, patients with PTSD demonstrated increased fear circuit activation, including the amygdala, regardless of experimental phase studied: conditioning, extinction learning, or extinction recall. Specifically, in the PTSD group, there was amygdala hyperactivation during conditioning followed by an inability to reduce its activation during extinction learning and extinction recall. In conjunction, there was a failure to activate the hippocampus and deactivate the parahippocampal gyrus during extinction learning. This activation pattern is in line with several PTSD neurocircuitry-based hypotheses, implicating deficient amygdala and hippocampus function across a variety of experimental paradigms (Liberzon and Sripada, Reference Liberzon and Sripada2008; Pitman et al., Reference Pitman, Rasmusson, Koenen, Shin, Orr, Gilbertson, Milad and Liberzon2012; Liberzon and Abelson, Reference Liberzon and Abelson2016). The amygdala, implicated in conditioning (LeDoux et al., Reference LeDoux, Iwata, Cicchetti and Reis1988; Phillips and LeDoux, Reference Phillips and LeDoux1992), and the hippocampus, implicated in successful extinction recall (Corcoran and Quirk, Reference Corcoran and Quirk2007; Quirk and Mueller, Reference Quirk and Mueller2008), are areas central to the ‘abnormal fear model’ (Liberzon and Sripada, Reference Liberzon and Sripada2008), with previous studies finding higher activation in the amygdala during extinction learning (Milad et al., Reference Milad, Pitman, Ellis, Gold, Shin, Lasko, Zeidan, Handwerger, Orr and Rauch2009) or extinction recall (Garfinkel et al., Reference Garfinkel, Abelson, King, Sripada, Wang, Gaines and Liberzon2014) in PTSD. Our results support and extend these findings to conditioning. An overactive amygdala, along with failure in hippocampus engagement, might be responsible for the prolonged and exaggerated threat response found in patients with PTSD (Liberzon and Sripada, Reference Liberzon and Sripada2008; Grillon et al., Reference Grillon, Pine, Lissek, Rabin, Bonne and Vythilingam2009; Liberzon and Abelson, Reference Liberzon and Abelson2016). This exaggerated threat response is further supported by studies reporting increased arousal (e.g. skin conductance responses) in patients with PTSD, compared to TEHC during conditioning (Diener et al., Reference Diener, Nees, Wessa, Wirtz, Frommberger, Penga, Ruttorf, Ruf, Schmahl and Flor2016), extinction learning (Wicking et al., Reference Wicking, Steiger, Nees, Diener, Grimm, Ruttorf, Schad, Winkelmann, Wirtz and Flor2016), and extinction recall (Milad et al., Reference Milad, Pitman, Ellis, Gold, Shin, Lasko, Zeidan, Handwerger, Orr and Rauch2009; Garfinkel et al., Reference Garfinkel, Abelson, King, Sripada, Wang, Gaines and Liberzon2014; Shvil et al., Reference Shvil, Sullivan, Schafer, Markowitz, Campeas, Wager, Milad and Neria2014; Wicking et al., Reference Wicking, Steiger, Nees, Diener, Grimm, Ruttorf, Schad, Winkelmann, Wirtz and Flor2016). These results suggest that patients with PTSD exhibit higher threat arousal through all experimental phases.

We observed consistent group differences in insula and ACC activation, which are part of the salience network (i.e. brain regions that select which stimuli deserve attentional resources deployment; Seeley et al., Reference Seeley, Menon, Schatzberg, Keller, Glover, Kenna, Reiss and Greicius2007). These regions have been implicated in threat detection (Critchley et al., Reference Critchley, Wiens, Rotshtein, Öhman and Dolan2004; Simmons et al., Reference Simmons, Matthews, Stein and Paulus2004; Ohman, Reference Ohman2005), as described in the ‘exaggerated threat detection model’ (Liberzon and Sripada, Reference Liberzon and Sripada2008; Grillon et al., Reference Grillon, Pine, Lissek, Rabin, Bonne and Vythilingam2009; Liberzon and Abelson, Reference Liberzon and Abelson2016). Recently, a conjoint insula-ACC activation has been proposed as the primary cortical correlate of increased sympathetic autonomic arousal and interoceptive awareness-appraisal (Harrison et al., Reference Harrison, Fullana, Soriano-Mas, Via, Pujol, Martínez-Zalacaín, Tinoco-Gonzalez, Davey, López-Solà, Pérez Sola, Menchón and Cardoner2015; Fullana et al., Reference Fullana, Harrison, Soriano-Mas, Vervliet, Cardoner, Àvila-Parcet and Radua2016). Accordingly, we show consistent higher insula activation during both conditioning and extinction learning. Like the amygdala, we found an initial insula and ACC hyperactivation during conditioning followed by a failure in insula to deactivate during extinction learning. Exaggerated threat attention and anticipation are common symptoms in PTSD. In a threat generalization task examining attention processes, where participants must discriminate between a CS+ and similar stimulus variants, insula activation was found to rise with increased stimulus resemblance to the CS+. Importantly, this increase was greater in PTSD compared to TEHC (Kaczkurkin et al., Reference Kaczkurkin, Burton, Chazin, Manbeck, Espensen-Sturges, Cooper, Sponheim and Lissek2016). It is likely that insula and amygdala hyperactivation during conditioning, coupled with a failure to deactivate it during extinction learning, leads to threat response overgeneralization, contributing to exaggerated emotional arousal. Like the insula, we also found consistent higher activation in the ACC during extinction recall. These results support previous findings of greater dACC (Milad et al., Reference Milad, Pitman, Ellis, Gold, Shin, Lasko, Zeidan, Handwerger, Orr and Rauch2009; Shvil et al., Reference Shvil, Sullivan, Schafer, Markowitz, Campeas, Wager, Milad and Neria2014) and ventral ACC involvement (Garfinkel et al., Reference Garfinkel, Abelson, King, Sripada, Wang, Gaines and Liberzon2014) during extinction recall in PTSD. Previous research has also implicated the dACC in threat appraisal and conditioned response expression (Etkin et al., Reference Etkin, Egner and Kalisch2011; Linnman et al., Reference Linnman, Zeidan, Furtak, Pitman, Quirk and Milad2012; Suarez-Jimenez et al., Reference Suarez-Jimenez, Bisby, Horner, King, Pine and Burgess2018). Our results support this ACC involvement during extinction recall suggesting that an overactive salience network might lead to poorer extinction recall through alertness to threat which is typical in PTSD. This exaggerated anticipation, or preparedness to threat, is further supported by higher threat subjective ratings during extinction recall (Diener et al., Reference Diener, Nees, Wessa, Wirtz, Frommberger, Penga, Ruttorf, Ruf, Schmahl and Flor2016).

In this meta-analysis, patients with PTSD exhibited higher hippocampal activation during all three learning phases. A detailed hippocampal sub-cluster inspection, however, reveals some major differences between phases. First, during conditioning, we found higher peak activation in both the posterior and anterior hippocampus in PTSD compared to TEHC. Second, during extinction learning, we found a cluster in the right parahippocampal gyrus that extended to the anterior hippocampus in PTSD compared to TEHC, whereas a left anterior hippocampal peak activation was found for TEHC compared to PTSD. Finally, during extinction recall, we found higher activation in the right anterior hippocampus originating from the amygdala in PTSD compared to TEHC. Interestingly, during extinction learning and extinction recall anterior hippocampus clusters in PTSD were more lateralized to the right side. These results diverge from some previous studies comparing patients with PTSD to TEHCs that found impaired hippocampal activation during extinction learning (Wicking et al., Reference Wicking, Steiger, Nees, Diener, Grimm, Ruttorf, Schad, Winkelmann, Wirtz and Flor2016), extinction recall (Garfinkel et al., Reference Garfinkel, Abelson, King, Sripada, Wang, Gaines and Liberzon2014), or found no group differences (Shvil et al., Reference Shvil, Sullivan, Schafer, Markowitz, Campeas, Wager, Milad and Neria2014). However, our meta-analysis focused on differential cue-conditioning paradigms, not on hippocampal-dependent context conditioning paradigms, in which different contexts are used to understand the context-CS representation relationship i.e. ‘deficient context processing model’ (Liberzon and Sripada, Reference Liberzon and Sripada2008), which could explain the lack of hippocampal specificity between the phases investigated in this paper.

The extinction learning and extinction recall processes also require cortical regulatory capacity over emotional-output areas in the hippocampus and amygdala. Our results show consistent higher vmPFC activation in patients with PTSD during conditioning and extinction recall. Higher vmPFC activation in PTSD was led by a hypoactivation when presented with a CS− during conditioning and a failure to deactivate when presented with CS+ during extinction recall. Furthermore, patients with PTSD showed a failure to engage the mPFC, particularly vmPFC and OFC, during extinction learning. Deficiencies in cortical areas regulatory capacities, including the vmPFC, over other emotional brain areas, such as the amygdala (Phan et al., Reference Phan, Fitzgerald, Nathan, Moore, Uhde and Tancer2005; Niendam et al., Reference Niendam, Laird, Ray, Dean, Glahn and Carter2012; Buhle et al., Reference Buhle, Silvers, Wager, Lopez, Onyemekwu, Kober, Weber and Ochsner2014), are implicated in the ‘diminished executive function and emotional regulation model’ (Liberzon and Sripada, Reference Liberzon and Sripada2008; Etkin et al., Reference Etkin, Egner and Kalisch2011). Accordingly, our results show a failure to activate the vmPFC activation during extinction learning in PTSD. In rodent models, the vmPFC has been implicated in extinction learning (Morgan and LeDoux, Reference Morgan and LeDoux1995; Milad and Quirk, Reference Milad and Quirk2002). In humans, the vmPFC engagement has also been associated with learning flexibility (Schiller et al., Reference Schiller, Levy, Niv, LeDoux and Phelps2008). Studies in PTSD have also found deficient vmPFC activation during extinction learning (Milad et al., Reference Milad, Pitman, Ellis, Gold, Shin, Lasko, Zeidan, Handwerger, Orr and Rauch2009) and greater activation during extinction recall (Garfinkel et al., Reference Garfinkel, Abelson, King, Sripada, Wang, Gaines and Liberzon2014) when compared to TEHC. Furthermore, a recent study in discrimination learning, using conditioning in healthy adults, found that vmPFC is particularly engaged for the process of cue discrimination rather than specific valence signaling (Suarez-Jimenez et al., Reference Suarez-Jimenez, Bisby, Horner, King, Pine and Burgess2018). Taken together, it is likely that dysregulation in the vmPFC, particularly during extinction learning, together with amygdala hyperactivation, may alter patients with PTSD ability to discriminate cues to regulate their emotional output and form novel safety cue memories and later recall them.

Finally, TEHC consistently exhibited higher thalamus activation across phases, driven by a failure to activate the thalamus in the PTSD group. The models mentioned above have all implicated functional deficits in the amygdala, PFC, and hippocampus in PTSD, underscoring the importance of intact communication between these brain regions in learning, memory, and emotion regulation. An important relay hub between different subcortical areas is the thalamus. Put differently, patients with PTSD may have a deficiency in network communication via the thalamus. The thalamus plays a significant role also in regulating arousal and awareness (Saalmann and Kastner, Reference Saalmann and Kastner2011; Venkatraman et al., Reference Venkatraman, Edlow and Immordino-Yang2017), and as part of the extended memory network has important implications in episodic and spatial memory (Cassel and Pereira de Vasconcelos, Reference Cassel and Pereira de Vasconcelos2015; Cholvin et al., Reference Cholvin, Hok, Giorgi, Chaillan and Poucet2018). Therefore, thalamus deficits could explain deficiencies in the memory formation network which could, in turn, explain patients with PTSD inability to use spatial cues to regulate arousal, leading to exaggerated emotional arousal and vigilance. These are preliminary conclusions as to our knowledge no differential cue-conditioning study to date has reported differences in thalamus activation between TEHC and PTSD. Some studies in patients with PTSD have reported thalamic activation without (Garfinkel et al., Reference Garfinkel, Abelson, King, Sripada, Wang, Gaines and Liberzon2014; Wicking et al., Reference Wicking, Steiger, Nees, Diener, Grimm, Ruttorf, Schad, Winkelmann, Wirtz and Flor2016) direct comparison to TEHC or across both TEHC and PTSD combined (Sripada et al., Reference Sripada, Garfinkel and Liberzon2013; Garfinkel et al., Reference Garfinkel, Abelson, King, Sripada, Wang, Gaines and Liberzon2014), while others found no differences in thalamus activation (Milad et al., Reference Milad, Pitman, Ellis, Gold, Shin, Lasko, Zeidan, Handwerger, Orr and Rauch2009; Steiger et al., Reference Steiger, Nees, Wicking, Lang and Flor2015; Diener et al., Reference Diener, Nees, Wessa, Wirtz, Frommberger, Penga, Ruttorf, Ruf, Schmahl and Flor2016). Nonetheless, a threat generalization tasks found higher thalamic activation associated with higher generalization in PTSD (Morey et al., Reference Morey, Dunsmoor, Haswell, Brown, Vora, Weiner, Stjepanovic, Wagner and LaBar2015), though others did not (Kaczkurkin et al., Reference Kaczkurkin, Burton, Chazin, Manbeck, Espensen-Sturges, Cooper, Sponheim and Lissek2016). Importantly, a recent meta-analysis found that the thalamus was activated during extinction learning in healthy adults (Fullana et al., Reference Fullana, Albajes-Eizagirre, Soriano-Mas, Vervliet, Cardoner, Benet, Radua and Harrison2018). Future studies should clarify PTSD/TEHC thalamus activation differences during conditioning.

Interestingly, peak activation in the cerebellum consistently emerged across all phases (i.e. conditioning, extinction learning, and extinction recall). Previous meta-analyses in healthy adults also found consistent activation of the cerebellum during conditioning (Fullana et al., Reference Fullana, Harrison, Soriano-Mas, Vervliet, Cardoner, Àvila-Parcet and Radua2016), and extinction learning (Fullana et al., Reference Fullana, Albajes-Eizagirre, Soriano-Mas, Vervliet, Cardoner, Benet, Radua and Harrison2018), highlighting the role of the cerebellum in fear learning processes. Our results suggest that the cerebellum could therefore also play an important role in fear learning in PTSD, which warrants further research.

Several limitations should be noted. First, the present meta-analysis included a relatively small number of studies, with only four studies that examined all three experimental phases (i.e. conditioning, extinction learning, extinction recall). Additionally, there were some differences in the results, such as for the amygdala, when including and excluding YN unpublished dataset, as this was the largest dataset we acquired. Nonetheless, the inclusion of original brain maps, comprising large sample size, confers it greater statistical power than would have achieved based on peak coordinates alone (Radua et al., Reference Radua, Mataix-Cols, Phillips, El-Hage, Kronhaus, Cardoner and Surguladze2012), thus increasing sensitivity in identifying the most robust brain activation effects across studies. Moreover, strong robustness analyses, showing results were replicable, with no evidence of heterogeneity or publication bias, supported the main findings, reinforcing our evaluation of the main findings. We acknowledge that the number of studies included does not provide the funnel plots with a strong representativity and should be noted while interpreting the funnel plot results. However, the combination of robustness analysis enhances the funnel plot results strength. This effect size and meta-analysis goes in line with recent ALE recommendations (Müller et al., Reference Müller, Cieslik, Laird, Fox, Radua, Mataix-Cols, Tench, Yarkoni, Nichols, Turkeltaub, Wager and Eickhoff2018), where the recommended number of studies for a meta-analysis is strongly dependent on the expected effect size. Still, as mentioned above AES-SDM as a neuroimaging meta-analytic approach improves upon the positive features of existing peak probability methods for meta-analysis, such ALE (Eickhoff et al., Reference Eickhoff, Laird, Grefkes, Wang, Zilles and Fox2009; Laird et al., Reference Laird, Eickhoff, Kurth, Fox, Uecker, Turner, Robinson, Lancaster and Fox2009) or MKDA (Wager et al., Reference Wager, Lindquist and Kaplan2007, Reference Wager, Lindquist, Nichols, Kober and Van Snellenberg2009). Second, due to insufficient data variability, we were unable to test for important regressors in PTSD research (e.g. sex, age, and symptom clusters). Future meta-analyses should include complete participant information, which would aid in characterizing vulnerable populations and PTSD sub-clusters. Additionally, task variability is a factor that could add heterogeneity to our data, although the I 2 statistic did not indicate so. Finally, we did not include ‘pure’ healthy controls as a comparison group. Finally, we did not include ‘pure’ healthy controls as a comparison group. Although several previous fMRI studies examining this population rarely assess trauma history and therefore we preferred to exclude such studies. Trauma-history is important in elucidating differences between exposure to trauma per se and PTSD.

Studying neural circuitry and mechanism is essential to understand the pathophysiology of PTSD. Elucidating the different neurobiological markers could help understand their specific role in PTSD symptomatology. In so, these markers could become targets for accurate diagnostic tools, which can also be used to identify vulnerable populations if they experienced a traumatic event. Moreover, brain activation and connections could aid in the development of targeted personalized treatments protocols, including pharmacological treatments and brain stimulation interventions, which is a much-needed shift in the clinical neuroscience field [for a review see Zuj and Norrholm (Reference Zuj and Norrholm2018)]. Future studies should also explore context integration during fear processes along with fMRI resting-state functional connectivity analysis, to further clarify PTSD neurobiological markers as the context is thought to play an important role in learning, predicting, and discriminating threat. Additionally, future studies should investigate the causality of the alteration found in the neural circuitry of PTSD to further elucidate whether these reflect a pre-existing vulnerability towards developing PTSD or if this is caused by the exposure to trauma and subsequent development of PTSD.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291719001387.

Author ORCIDs

Benjamin Suarez-Jimenez, 0000-0002-4765-2458.

Acknowledgments

We thank the following authors for providing additional data or information in support of the meta-analyses: Slawomira J. Diener, Herta Flor, Antonia N. Kaczkurkin, Kevin S. LaBar, Shmuel Lissek, Rajendra A. Morey, Frauke Nees, and Manon Wicking. Dr Suarez-Jimenez's role in this project is supported by grant T32MH015144 and K01 MH118428-01 from the National Institute of Mental Health. Dr Lazarov's role in this project is supported by grant T32MH020004 from the National Institutes of Mental Health. A/Prof. Harrison is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (NHMRC) Clinical Career Development Award (1124472). Dr Radua's role in this project is supported by a ‘Miguel Servet' contract from the Carlos III Health Institute, and FEDER grant (Spain; CP14/00041). Dr Neria's role in this project is supported by grants R01MH105355 and R01MH072833 from the National Institute of Mental Health. Also, he is supported by the New York State Psychiatric Institute. Dr Fullana's role in this project was supported by Carlos III Health Institute and FEDER grant (Spain; PI16/00144).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.