Introduction

In spite of considerable changes in attitude towards sexual minorities, lesbians, gay men, and bisexual individuals continue to encounter discrimination and obstacles in their social, political, and cultural environments (Pitoňák, Reference Pitoňák2017). Since there is strong evidence that discriminating contexts and policies (such as prohibiting same-sex marriage) stigmatize gay men and predict mental health problems (Hatzenbuehler, Keyes, & Hasin, Reference Hatzenbuehler, Keyes and Hasin2009; Hatzenbuehler, Phelan, & Link, Reference Hatzenbuehler, Phelan and Link2013; LeBlanc, Frost, & Bowen, Reference LeBlanc, Frost and Bowen2018; Meyer, Luo, Wilson, & Stone, Reference Meyer, Luo, Wilson and Stone2019), it is not surprising that several meta-analyses revealed that psychiatric disorders such as anxiety and depression are much more prevalent among sexual minorities than heterosexuals (King et al., Reference King, Semlyen, Tai, Killaspy, Osborn, Popelyuk and Nazareth2008; Plöderl, Sauer, & Fartacek, Reference Plöderl, Sauer and Fartacek2006; Semlyen, King, Varney, & Hagger-Johnson, Reference Semlyen, King, Varney and Hagger-Johnson2016). Compared to heterosexual men, gay and bisexual men are 2.58 times more prone to lifetime depression, 1.88 times more prone to a last-year anxiety disorder, and 1.55 times more prone to last-year alcohol dependence (King et al., Reference King, Semlyen, Tai, Killaspy, Osborn, Popelyuk and Nazareth2008). A study by Gonzales, Przedworski, and Henning-Smith (Reference Gonzales, Przedworski and Henning-Smith2016) indicated that 25.9% of gay men compared to 16.9% of heterosexual men suffered from moderate or severe symptoms of psychological distress. In addition, a national study in Australia found that homosexuality is a potential risk factor for men's mental health (Swannell, Martin, & Page, Reference Swannell, Martin and Page2016).

Another critical health issue among sexual minorities is a suicide, now considered a contemporary social problem (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, 2021), as meta-analytic data suggests that compared to heterosexuals, sexual minorities experience suicidal ideation twice as often, attempt suicide requiring medical attention four times more frequently and commit suicide three times more often (Marshal et al., Reference Marshal, Dietz, Friedman, Stall, Smith, McGinley and Brent2011). Other meta-analyses showed that sexual minorities reported more suicide attempts and ideation than heterosexual individuals (Hottes, Bogaert, Rhodes, Brennan, & Gesink, Reference Hottes, Bogaert, Rhodes, Brennan and Gesink2016; King et al., Reference King, Semlyen, Tai, Killaspy, Osborn, Popelyuk and Nazareth2008; Plöderl et al., Reference Plöderl, Sauer and Fartacek2006).

In a Taiwanese study, 31% of gay and bisexual men reported past-year suicidal ideation or an attempt (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Ko, Hsiao, Chen, Lin and Yen2019). Early coming-out, homophobic bullying, and lack of family support were found to predict suicidal ideation or attempt (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Ko, Hsiao, Chen, Lin and Yen2019). Other studies found that shame triggered by family and cultural pressure, lack of social support, victimization, discrimination, poor-quality relationships, and family rejection predicted suicidal attempts among sexual minorities (Kazan, Calear, & Batterham, Reference Kazan, Calear and Batterham2016; Marshal et al., Reference Marshal, Dietz, Friedman, Stall, Smith, McGinley and Brent2011; Matarazzo et al., Reference Matarazzo, Barnes, Pease, Russell, Hanson, Soberay and Gutierrez2014; McDermott & Roen, Reference McDermott and Roen2016; Ryan, Huebner, Diaz, & Sanchez, Reference Ryan, Huebner, Diaz and Sanchez2009) When considering completed suicides, Swedish men in same-sex registered partnerships or marriages revealed a threefold increased risk of suicide compared to men in different-sex marriages (Björkenstam, Andersson, Dalman, Cochran, & Kosidou, Reference Björkenstam, Andersson, Dalman, Cochran and Kosidou2016) and Danish men in a same-sex registered domestic partnership experienced an eight times higher number of completed suicides than men in same-sex marriages, and twice the suicide mortality than men who have never been married (Mathy, Cochran, Olsen, & Mays, Reference Mathy, Cochran, Olsen and Mays2011). According to a review, mental disorders are the single greatest risk factor for suicidal behavior in sexual minorities (Haas et al., Reference Haas, Eliason, Mays, Mathy, Cochran, D'Augelli and Rosario2010). Nevertheless, after controlling for mental disorders, the rate of suicide attempts remained two to three times higher than in heterosexual individuals (Haas et al., Reference Haas, Eliason, Mays, Mathy, Cochran, D'Augelli and Rosario2010), implying that stigma, prejudice, and discrimination are other potentially relevant factors in explaining suicidality.

Islam and homosexuality

Islamic law (Shariah) and oral teachings of the prophet Muhammad (Ahadith) classify same-sex sexual relationships and homosexuality as ‘unethical’ (Bouhdiba, Reference Bouhdiba2004). Many Muslims, therefore, consider homosexuality a ‘deviation from nature’ and ‘rebellion against God’ (Jaspal, Reference Jaspal and A. Naples2016). Homosexuality is forbidden in the majority of Islamic countries. Worldwide, same-sex sexual behavior is punishable by death in a total of 10 countries and four regions, all of which are Islamic. These countries include Afghanistan, Brunei, Iran, Mauritania, Pakistan, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, United Arab Emirates, and Yemen, while the regions are located in Nigeria, Somalia, Syria, and Iraq (Jaspal, Reference Jaspal and A. Naples2016).

Islamic clergymen (Foghaha) forbid homosexuality by relying on the story of the people of Lot destroyed by God (Quran's 7th Surah, verses 80 and 81) supposedly for their same-sex sexual activities (Bucar & Shirazi, Reference Bucar and Shirazi2012). Islamic thinkers claim that setting such Islamic rules promote the individual's and society's health, and that same-sex sexual activity must be prohibited because of its ‘destructive nature for human health’ (Deuraseh, Reference Deuraseh2008).

According to Pew Research Center (2013), the acceptance of homosexuality in Islamic countries is very low. For instance, its acceptance rate in Egypt and Pakistan is under 5%; the highest rate of homosexuality acceptance in an Islamic country is in Lebanon (18%). In comparison, Western countries like Canada and Great Britain have acceptance rates of 80 and 76%, respectively (Pew Research Center, 2013).

Despite the opposition to the homosexuality of most Islamic thinkers, the Quran contains no reference to same-sex activity, nor is the prohibition of homosexuality specifically mentioned: several pioneering Islamic thinkers claim that the destruction of the people of Lot was not for same-sex sexual activities, but rather – relying on Quranic verses – they state other reasons including disobedience to Allah, murder, and robbery (Bucar & Shirazi, Reference Bucar and Shirazi2012).

Iran and homosexuality

Iran is a country whose citizens follow Islam, harbor negative attitudes towards homosexuality, and support severe punishments for same-sex sexual contacts. According to the Islamic Penal Code, the punishment for having anal intercourse between two men (livat) is execution, while it is 100 lashes for rubbing the penis between the legs of a male sexual partner (tafkhiz) (Jaspal, Reference Jaspal and A. Naples2016; Karimi & Bayatrizi, Reference Karimi and Bayatrizi2019). Homosexuality in Iran is almost always referred to negatively: the most common expression for gay men as ‘kuni’ is synonymous with the English epithet ‘bugger’. Although international health experts claim that homosexuality is not chosen and cannot be changed (Healthy Children, 2021), some experts in Iran try to do so, or recommend and perform sex-reassignment surgery in gay men. Moreover, the first author of this article observed that some Iranian psychotherapists are practicing discredited psychotherapy (American Psychological Association, 2011), such as teaching gay men negative and degrading perceptions of their sexual orientation in an attempt to alter their sexual orientation.

Murray (Reference Murray, Murray and Roscoe1997) states that there is a shared culture in Islamic countries that rejects homosexuality. Iran practices specific forms of rejection such as (1) total denial of homosexuality by the government (e.g. president Ahmadinejad's expression in 2007 ‘In Iran, we don't have homosexuals’) (Whitaker, Reference Whitaker2007), (2) due to its rejection in academia, virtually no research has been carried out on gay men in Iran to date, and (3) another common form is sexual-reassignment surgery for gay men (Najmabadi, Reference Najmabadi2005). These forms of rejection, which are based on Iranian interpretations of Islam, are likely to put gay men under severe stress and endanger their mental health.

The aim of the present study is to investigate the percentage of mental health problems and suicidality in Iranian gay men, thereby enabling the first empirical study of this population. In addition, we wanted to see whether mental health symptoms and suicidality correlate in Iranian gay men. Thirdly, we aimed to descriptively compare the rate of mental health problems and suicidality between Iranian gay men with population-based findings.

Methods

Participants

Study recruitment was done in Tehran, Iran by the first author. Due to the illegality of homosexuality in Iran and the dangers gay men face, the researcher employed snowball sampling with three seeds. Three intermediaries introduced the research to gay men and invited them to participate during 11 waves of gay meetings and celebrations which were attended by a large number of gay men.

Almost all participants were residing in Tehran. Most were long-time residents, while some had migrated to Tehran during recent months or years. The participants could choose whether the data was collected on a paper–pencil questionnaire filled out at the researcher's workplace, on the university campus, or at their homes. Most preferred to complete the questionnaire at home. All participants provided oral informed consent to participate in the study. They were guaranteed the anonymity and confidentiality of their data.

Totally, n = 215 participants took part in the study and n = 2 were excluded from analyses due to incomplete information in the questionnaire. Our final sample thus consisted of N = 213 gay men. Inclusion criteria were: identifying as a gay man, being at least 18 years old, and having enough education and literacy to comprehend the questionnaire items. The participants in the final sample were aged 18–49 years (s.d. = 9.522). Of these, n = 144 participants had an academic degree and n = 69 a diploma. Please note that education up to a diploma, usually obtained at age 18 years, is mandatory in Iran. The preferred sex position of n = 118 (55.40%) participants was versatile, of n = 54 (25.35%)bottom, and of n = 41 (19.25%) top. Many participants refused to answer further sociodemographic variables, mostly out of fear of being identifiable. However, of those who did provide an answer, 8 (3.75%) had previously been married to a woman and divorced, 158 participants (74.18%) were in a relationship, and 38 (17.84%) gay men reported that their families were aware of their sexual identity. The participants who provided answers were coming from five different provinces in Iran, with the majority stemming from one of the areas of Tehran. Furthermore, none reported that they had undergone gender reassignment surgery, although this was often recommended by therapists. Additionally, 29 (13.62%) participants reported having been detained at parties and released due to lack of evidence of a crime. Participants who reported severe psychiatric symptoms or who were at risk of a suicide attempt were referred to a psychiatrist.

Questionnaires

Symptom Checklist-90

To assess mental health problems we relied on the 90-item Symptom Checklist-90 by Derogatis, Lipman, and Covi (Reference Derogatis, Lipman and Covi1973). Its items are based on a five-point Likert scale (0 = not at all, 1 = a little bit, 2 = moderately, 3 = quite a bit, 4 = extremely) and assess mental health issues in the last 7 days. The questionnaire includes nine sub-scales (somatization, obsessive–compulsive, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, and psychoticism). The sub-scales are added up to arrive at the global severity index (GSI) by forming the mean score. The GSI is preferable for analyses (Derogatis et al., Reference Derogatis, Lipman and Covi1973) since the sub-scales did not differentiate well in factor analyses (Cyr, McKenna-Foley, & Peacock, Reference Cyr, McKenna-Foley and Peacock1985; Schmitz et al., Reference Schmitz, Hartkamp, Kiuse, Franke, Reister and Tress2000). A GSI or sub-scale mean score from 0 to 1 indicates no symptoms, a mean score from 1.01 to 2 minor symptoms, a mean score from 2 to 3.1 moderate symptoms, and a mean score from 3.1 to 4 severe symptoms (Mirzaei, Reference Mirzaei1980). According to previous studies, this questionnaire is quite reliable (Derogatis, Reference Derogatis1994) and valid (Derogatis & Cleary, Reference Derogatis and Cleary1977; Fridell, Cesarec, Johansson, & Malling Thorsen, Reference Fridell, Cesarec, Johansson and Malling Thorsen2002; Mirzaei, Reference Mirzaei1980). Its internal consistency was α = 0.71 in the current study.

Beck's scale for suicidal ideation

To assess suicidality we used the 19-item Beck's Scale for Suicidal Ideation (BSSI) by Beck, Kovacs, and Weissman (Reference Beck, Kovacs and Weissman1979). The BSSI measures attitudes towards and planning to commit suicide during the last week. Its items include (1) wish to live, (2) wish to die, (3) reasons for living/dying, (4) desire to make an active suicide attempt, (5) passive suicidal desire, (6) duration of suicide ideation, (7) frequency of ideation, (8) attitude toward ideation, (9) control over suicidal action, (10) deterrents to active attempt, (11) reason for a contemplated attempt, (12) specificity/planning of contemplated attempt, (13) availability/opportunity for a contemplated attempt, (14) capability to carry out attempt, (15) expectancy/anticipation of actual attempt, (16) actual preparation for contemplated attempt, (17) suicide note, (18) final acts in anticipation of death, and (19) deception/concealment of contemplated suicide. Since each item is scored from 0 to 2, the scale's total score varies from 0 to 38. Higher scores are indicative of higher suicidality. If participants score 0 in the first five items, they are revealing no suicidal ideation and they need not answer the remaining items. Scores from 1 to 5 indicate suicidal ideation, scores from 6 to 19 indicate an individual's preparing to commit suicide (suicide threat), and scores from 20 to 38 indicate the ultimate decision to commit suicide (suicide attempt). This questionnaire's internal consistency was α = 0.89 and inter-rater reliability r = 0.83 (Wasserman, Reference Wasserman2016). Its concurrent validity with the Suicidal Risk Assessment Scale was r = 0.69 (Ducher & Daléry, Reference Ducher and Daléry2004). The BSSI's internal consistency was found to be good in an Iranian study (α = 0.84) (Esfahani, Hashemi, & Alavi, Reference Esfahani, Hashemi and Alavi2015), and in this one (α = 0.82).

Statistical analyses

We computed means and standard deviations for SCL-90 and BSSI sub-scales and total scales. We reported how many participants reported no, minor, moderate, and severe symptoms in SCL-90 sub-scales and the total scale (Mirzaei, Reference Mirzaei1980) and how many individuals possessed suicidal ideation, threat, and attempt in the BSSI. We computed correlation coefficients between the GSI and BSSI scores as well as between these scores with age and education as sociodemographic variables. Whenever a correlation was computed for GSI, we applied the Spearman correlation because its total score is skewed, since only those individuals who reported suicidal ideation in the first five items would have continued to answer the remaining ones (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Kovacs and Weissman1979). All other correlations were Pearson ones. For the correlations, we computed the Cohen's d effect size. All analyses were conducted in IBM SPSS Statistics 22.

Results

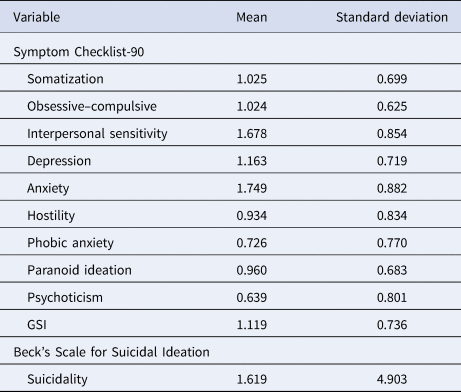

The SCL-90 sub-scale's mean scores varied between M = 0.639 (s.d. = 0.801) in psychoticism and M = 1.749 (s.d. = 0.882) in anxiety (Table 1). The GSI had a mean score of M = 1.119 (s.d. = 0.736). When applying the GSI cut-offs suggested by Mirzaei (Reference Mirzaei1980), we observed that 60.56% (n = 129) of the participants reported no mental health problems, 27.7% (n = 59) minor symptoms, 7.51% (n = 16) reported moderate symptoms, and 4.23% (n = 9) of the participants revealed severe mental health problems in the last week. Information on sub-scales is found in Table 2.

Table 1. Scales' means and standard deviations

Note. GSI, global severity index.

Table 2. Descriptive results in Symptom Checklist-90

Note. n, number; %, percentage of N = 213; GSI, global severity index.

In the BSSI, the gay men reported a mean score of M = 1.619 (s.d. = 4.903). Note that a large s.d. is to be expected in this case (Esfahani et al., Reference Esfahani, Hashemi and Alavi2015), because of the BSSI scale's skewness (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Kovacs and Weissman1979). 80.28% (n = 171) of the participants reported no suicidal ideation, 19.72% (n = 42) possessed suicidal ideation, 7.51% (n = 16) reported suicidal threat, and 1.88% (n = 4) possessed suicidal attempt (Table 3). Note that those with suicidal threat are a subgroup among those with suicidal ideation, and those with suicidal attempt are again a subgroup among those with the suicidal threat.

Table 3. Descriptive results in Beck's scale for suicidal ideation

Note. n, number; %, percentage of N = 213, individuals with suicidal threat are a sub-group among those with suicidal ideation, individuals with suicidal attempt are a sub-group among those with a suicidal threat.

The Spearman correlation coefficient between GSI and the BSSI scores was r = 0.71, p < 0.01, d = 1.62. Stronger mental health symptoms were thus associated with higher suicidality to a large degree (Cohen, Reference Cohen1992).

The Pearson correlation coefficient between age and GSI was r = −0.32, p < 0.01, d = 0.68, while the Pearson correlation between education and GSI was r = −0.28, p < 0.01, d = 0.58. The Spearman correlation coefficient between age and the BSSI score was r = −0.37, p < 0.01, d = 0.80, while the Spearman correlation between education and the BSSI score was r = −0.35, p < 0.01, d = 0.75. Hence, older Iranian gay men revealed fewer mental health problems and suicidality. All effect sizes between these sociodemographic variables, suicidality, and mental health problems were at a medium level, with the exception of the correlation between age and suicidality, which was strong (Cohen, Reference Cohen1992).

Discussion

The current study provides initial evidence of the mental health status and suicidality rate among gay men in Iran. Relying on cut-offs in the SCL-90 (Mirzaei, Reference Mirzaei1980), we found that 27.7% of Iranian gay men have minor mental health symptoms, 7.51% reported moderate symptoms, 4.23% severe symptoms, and 60.56% reported no mental health symptoms. A total of 39.44% of gay men were thus suspected to be suffering minor to serious mental health problems. This percentage is higher than in the general population of Iranian males, as a previous study using random sampling methods found that the risk of mental health problems in Iranian males aged 10 years and older was 19.28% (CI 18.71–19.87) (Noorbala et al., Reference Noorbala, Bagheri Yazdi, Faghihzadeh, Kamali, Faghihzadeh, Hajebi and Ghafarzadeh2017) in the General Health Questionnaire 28 (GHQ-28) (Goldberg & Hillier, Reference Goldberg and Hillier1979), assessing ‘recent’ mental health issues. In an earlier study in Tehran, also applying the GHQ-28, 28.6% of males 15 years and older were affected by mental health problems (Noorbala, Bagheri Yazdi, Asadi Lari, & Vaez Mahdavi, Reference Noorbala, Bagheri Yazdi, Asadi Lari and Vaez Mahdavi2011), a number again lower than that in this study conducted on gay men in Tehran.

Comparing these results descriptively, it seems likely that Iranian gay men suffer from more mental disorders than Iranian heterosexual men. Moreover, as our study's gay men exhibited more mental health problems and suicidality when they reported having less education – a finding in line with an Iranian population-based sample's (Noorbala et al., Reference Noorbala, Bagheri Yazdi, Faghihzadeh, Kamali, Faghihzadeh, Hajebi and Ghafarzadeh2017) – Iran's overall population of gay men may be suffering even more symptoms of mental disorders and suicidality than our snowball sample of highly educated gay men. On the other hand, similar to earlier research (Bybee, Sullivan, Zielonka, & Moes, Reference Bybee, Sullivan, Zielonka and Moes2009) we found that younger gay men have more mental health problems than older ones. This younger-age discrepancy in mental-health pathology may have to do with lessening dependence on parental and societal support with increasing age (Bybee et al., Reference Bybee, Sullivan, Zielonka and Moes2009), and the greater individuation and increased gay community support of gay men. Note that the relationship between age and mental health was reversed in the Iranian general population, as older individuals reported more mental health problems (Noorbala et al., Reference Noorbala, Bagheri Yazdi, Faghihzadeh, Kamali, Faghihzadeh, Hajebi and Ghafarzadeh2017).

Our findings are comparable to those in Western and Eastern cultures (Frost, Lehavot, & Meyer, Reference Frost, Lehavot and Meyer2015; Hottes et al., Reference Hottes, Bogaert, Rhodes, Brennan and Gesink2016; King et al., Reference King, Semlyen, Tai, Killaspy, Osborn, Popelyuk and Nazareth2008; Marshal et al., Reference Marshal, Dietz, Friedman, Stall, Smith, McGinley and Brent2011; Pepping et al., Reference Pepping, Lyons, McNair, Kirby, Petrocchi and Gilbert2017; Pitoňák, Reference Pitoňák2017; Plöderl et al., Reference Plöderl, Sauer and Fartacek2006; Sattler & Lemke, Reference Sattler and Lemke2019; Shenkman & Shmotkin, Reference Shenkman and Shmotkin2010; Silenzio, Pena, Duberstein, Cerel, & Knox, Reference Silenzio, Pena, Duberstein, Cerel and Knox2007; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Ko, Hsiao, Chen, Lin and Yen2019), indicating that gay men carry higher risks for mental health problems. While these findings are in line with the minority stress theory's proposition that sexual minorities have a greater risk for mental disorders because of minority stress (Meyer, Reference Meyer2003), future between-group studies are needed to enable specific mental-health comparisons between Iranian gay and heterosexual men as well as within-group studies testing whether minority stress predicts mental health problems in Iranian gay men.

In the present study, we also found that 19.72% of the participants reported last-week suicidal ideation, 7.51% last-week suicidal threat, and 1.88% last-week suicidal attempt, while 80.28% of the participants reported no suicidal ideation in the last week. Consistently, an international meta-analysis found that 25.78% of men who have sex with men (MSM) and reside in low- and middle-income countries reported a lifetime prevalence of suicidal ideation (Luo, Feng, Fu, & Yang, Reference Luo, Feng, Fu and Yang2017). This number is considerably lower than the lifetime prevalence of suicidal ideation of MSM living in high-income countries of 42.55% (Luo et al., Reference Luo, Feng, Fu and Yang2017). Previous studies on the Iranian general population of 15 years and older found last-year suicidal ideation in 5.7%, last-year suicidal threat in 2.9%, and last-year suicidal attempt in 1% of the subjects (Malakouti et al., Reference Malakouti, Nojomi, Bolhari, Hakimshooshtari, Poshtmashhadi and De Leo2009). Even though ours was a 1-week framework, Iranian gay men in our sample showed more suicidal ideation, threat, and attempt than the general population. Both 1-year and lifetime suicidality of Iranian gay men are apt to be higher than the past-week suicidality assessed in our study. Furthermore, as we hypothesized, mental health problems and suicidality correlated closely in our study. This too matches with findings in previous studies (Haas et al., Reference Haas, Eliason, Mays, Mathy, Cochran, D'Augelli and Rosario2010).

It is likely that the Islamic tradition's strict prohibition of homosexuality causes unique stress for gay men, thereby endangering their mental health. To improve the mental health of gay men, the societal threat and stigma on gay men must be reduced. In accordance with international human rights laws (Hood, Reference Hood2001), the first step should be to decriminalize same-sex sexual contacts – with priority on abolishing capital punishment. Further steps would be to de-stigmatize homosexuality by passing anti-discrimination and hate-crime laws, as well as legalizing same-sex marriage. As it was argued earlier that human as well as LGBT rights struggles should take the local culture into account (Karimi & Bayatrizi, Reference Karimi and Bayatrizi2019), shifting Iranian culture's stance on homosexuality should exploit the fact that there is no explicit prohibition of homosexuality in the Quran (Bucar & Shirazi, Reference Bucar and Shirazi2012) and amplify the voices of modern Islamic thinkers considering homosexuality a natural manifestation of human sexuality (Alipour, Reference Alipour2017). Since taking a positive or neutral stance on homosexuality is nothing new in Iran, a shift toward the positive and affirmative should make use of and reclaim these ideas: prominent poets such as Sa'di, Hafiz, Manoochehri, Farokhi Sistani, Jami, and textbooks including Rasm al Tavarikh and Qaboosnameh mention homosexuality and the expression ‘shahedbazi’ – a neutral equivalent to homosexuality – frequently (Shamisa, Reference Shamisa2002).

Limitations of the current study include that – due to Iranian laws – our recruiting had to be done secretly. We therefore had to rely on snowball sampling, which means many drawbacks, such as little likelihood of identifying gay men with few social contacts (e.g. those who had migrated to Tehran only recently and those who were refraining from contact with the gay community), or lack of trust in the researcher. Biases in our data include most of our participants' high education level, as most have an academic degree. Furthermore, we gathered only oral, not written informed consent to keep our participants out of danger. Despite these drawbacks, our study provides the first valuable documentation of the mental health situation and suicidality of Iranian gay men and therefore an important basis for future research on this population.

To conclude: mental health problems and suicidality correlate highly in Iranian gay men. When descriptively comparing these factors with Iran's general population, gay men in Iran are experiencing more mental health problems and greater suicidality, including suicidal ideation, threat, and attempt.