Introduction

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a pervasive mental disorder characterized by disturbed identity, impaired emotion regulation, and marked impulsivity (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Impulsivity in BPD patients manifests in a range of dangerous and (self-) destructive behaviors such as drug abuse, self-harm, and suicidal behavior and, as such, can lead to serious consequences. However, impulsivity is a heterogeneous concept with several different subtypes associated with different measures that are rarely examined in a complex manner. Comprehensive analysis of impulsivity dimensions can lead to the specification of self-control impairment in a given patient group and, consequently, to tailoring individually suitable forms of psychotherapeutic (Stoffers-Winterling et al., Reference Stoffers-Winterling, Völlm, Rücker, Timmer, Huband and Lieb2012) or biological treatment (Lieb et al., Reference Lieb, Völlm, Rücker, Timmer and Stoffers2010; Svěrák et al., Reference Svěrák, Linhartová, Fiala, Kašpárek and Ustohal2018).

Impulsivity is considered either a consequence of some personality traits or a dysfunction of a neurobiological or cognitive function (Linhartová et al., Reference Linhartová, Širůček, Ejova, Barteček, Theiner and Kašpárek2019). The most up-to-date complex personality model of impulsivity is the UPPS-P questionnaire (Whiteside and Lynam, Reference Whiteside and Lynam2001; Cyders and Smith, Reference Cyders and Smith2007). BPD patients have been found to have increased impulsivity in all UPPS-P dimensions except sensation seeking, i.e. in lack of premeditation, lack of perseverance, negative urgency, and positive urgency (Bøen et al., Reference Bøen, Hummelen, Elvsåshagen, Boye, Andersson, Karterud and Malt2015; Paret et al., Reference Paret, Hoesterey, Kleindienst and Schmahl2016). Two broad subtypes of behavioral dimensions of impulsivity were defined in the literature: impulsive action and impulsive choice (Winstanley et al., Reference Winstanley, Eagle and Robbins2006). Impulsive action can be further divided into waiting impulsivity (difficulties inhibiting premature actions) and stopping impulsivity (difficulties interrupting ongoing actions) (Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Eagle, Economidou, Theobald, Mar, Murphy, Robbins and Dalley2009). In most previous studies, BPD patients have been found to have increased impulsive choice, but intact waiting and stopping impulsivity (Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Eagle, Economidou, Theobald, Mar, Murphy, Robbins and Dalley2009; Jacob et al., Reference Jacob, Gutz, Bader, Lieb, Tüscher and Stahl2010; Hagenhoff et al., Reference Hagenhoff, Franzen, Koppe, Baer, Scheibel, Sammer, Gallhofer and Lis2013; Legris et al., Reference LeGris, Toplak and Links2014; Barker et al., Reference Barker, Romaniuk, Cardinal, Pope, Nicol and Hall2015; van Eijk et al., Reference van Eijk, Sebastian, Krause-Utz, Cackowski, Demirakca, Biedermann, Lieb, Bohus, Schmahl, Ende and Tüscher2015; Berenson et al., Reference Berenson, Gregory, Glaser, Romirowsky, Rafaeli, Yang and Downey2016; Paret et al., Reference Paret, Jennen-Steinmetz and Schmahl2017).

Impulsivity manifested in behavioral tests, alongside increased impulsivity itself, may be associated with impaired cognitive functions necessary for task performance such as attention, working memory, and executive functioning (Bazanis et al., Reference Bazanis, Rogers, Dowson, Taylor, Meux, Staley, Nevinson-Andrews, Taylor, Robbins and Sahakian2002; Lampe et al., Reference Lampe, Konrad, Kroener, Fast, Kunert and Herpertz2007; Nigg, Reference Nigg2017). Research on cognitive functions in BPD patients has generally produced mixed results (e.g. Feliu-Soler et al., Reference Feliu-Soler, Soler, Elices, Pascual, Pérez, Martín-Blanco, Santos, Crespo, Pérez and Portella2013; Hagenhoff et al., Reference Hagenhoff, Franzen, Koppe, Baer, Scheibel, Sammer, Gallhofer and Lis2013). According to a recent meta-analysis, most studies found worse performance in some cognitive domains, but they do not indicate a specific cognitive function in which BPD patients fail consistently (Mcclure et al., Reference McClure, Hawes and Dadds2016).

The diverse results of studies on cognitive functioning in BPD could be related to comorbidities in BPD samples. Some comorbidities, such as major depression, bipolar disorder, and psychotic disorders, are usually excluded from research samples. However, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in BPD patients is often neglected. ADHD is associated with substantial deficits in cognitive functioning. Results of existing meta-analyses suggest that patients with ADHD, in comparison to healthy controls, have worse performance in attention, working memory, planning, and organization (Alderson et al., Reference Alderson, Kasper, Hudec and Patros2013; Mowinckel et al., Reference Mowinckel, Pedersen, Eilertsen and Biele2015; Pievsky and McGrath, Reference Pievsky and Mcgrath2018). Hence, not controlling for ADHD comorbidity in BPD samples could lead to biased results in tests of cognitive functioning. BPD patients with comorbid ADHD were found to have worse cognitive performance than healthy people and worse than BPD patients without ADHD comorbidity (Lampe et al., Reference Lampe, Konrad, Kroener, Fast, Kunert and Herpertz2007). Studies that excluded ADHD comorbidity suggest that BPD patients show deficits in working memory (Stevens et al., Reference Stevens, Burkhardt, Hautzinger, Schwarz and Unckel2004; Hagenhoff et al., Reference Hagenhoff, Franzen, Koppe, Baer, Scheibel, Sammer, Gallhofer and Lis2013).

ADHD comorbidity in BPD patients could also lead to distorted impulsivity test results. ADHD patients, as opposed to BPD patients, have been found to have increased waiting and stopping impulsivity (Lampe et al., Reference Lampe, Konrad, Kroener, Fast, Kunert and Herpertz2007; Pani et al., Reference Pani, Menghini, Napolitano, Calcagni, Armando, Sergeant and Vicari2013). Patients with ADHD and patients with BPD have been found to have increased impulsive choice and UPPS-P dimensions, with the exception of sensation seeking (Toplak et al., Reference Toplak, Jain and Tannock2005; Lopez et al., Reference Lopez, Dauvilliers, Jaussent, Billieux and Bayard2015; Patros et al., Reference Patros, Alderson, Kasper, Tarle, Lea and Hudec2016; Pedersen et al., Reference Pedersen, Walther, Harty, Gnagy, Pelham and Molin2016), with one study showing higher lack of premeditation and higher lack of perseverance in ADHD patients as compared to BPD patients (Krause-Utz et al., Reference Krause-Utz, Cackowski, Daffner, Sobanski, Plichta, Bohus, Ende and Schmahl2016).

Aims and hypotheses

The current study provides a comprehensive evaluation of essential self-reported and behavioral impulsivity dimensions as well as cognitive functions in a sample of patients with BPD who are not affected by ADHD, major depression, bipolar disorder, psychotic disorder, or addiction. The impulsivity profile is compared with a sample of healthy controls and patients with ADHD (without BPD comorbidity). Based on previous research described in the Introduction, we hypothesize that BPD patients, as well as ADHD patients, show increased impulsivity in all UPPS-P subscales except sensation seeking and increased impulsive choice as compared to healthy controls. Further, we hypothesize that BPD patients, unlike ADHD patients, have intact impulsive action as compared to healthy controls. No specific hypotheses were made about cognitive function domains in BPD due to conflicting literature, but we test the hypothesis that only ADHD patients, but not BPD patients, have worse cognitive performance than healthy controls.

Methods

The study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of University Hospital Brno. Before the research procedure was carried out, the study was explained thoroughly to the subjects who then signed informed consent forms. The research was carried out in accordance with APA ethical standards.

Participants

The study included 39 patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD), 25 patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and 55 healthy controls (HC). The HC group was a pooled sample of healthy controls matched to BPD and ADHD patients by age, sex, and education level. HC were recruited through internet advertisement. The Mini international neuropsychiatric interview (MINI; Sheehan et al., Reference Sheehan, Lecrubier, Sheehan, Amorim, Janavs, Weiller, Hergueta, Baker and Dunbar1998) was conducted with the HC to confirm the absence of any mental disorder. The BPD and ADHD patients were recruited at the Department of Psychiatry of the University Hospital Brno and through outpatient psychiatrists in the Czech Republic. The data included available patient documentation, patient charts, mental status examinations, and comprehensive interviews similar in structure to the comprehensive assessment of symptoms and history (Andreasen, Flaum, and Arndt, Reference Andreasen, Flaum and Arndt1992) focused on patient history, pharmacological history, past symptoms, and the course of the disorder.

The BPD diagnosis was confirmed by two board-certified psychiatrists according to DSM-5 criteria and by a trained psychologist using the Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines – Revised (DIB-R; Zanarini et al., Reference Zanarini, Gunderson, Frankenburg and Chauncey1989). According to DIB-R, a patient is assessed with BPD if they score at least 8 out of 10 points, with higher scores indicating more severe BPD. In the present sample, 12 patients (31%) scored in DIB-R 8 points, 9 patients (23%) scored 9 points, and 18 patients (46%) scored 10 points. If comorbid ADHD was suspected in the BPD patients, the Diagnostic Interview for ADHD in Adults 2.0 (DIVA 2.0; Kooij and Francken, Reference Kooij2010) was performed to exclude the ADHD comorbidity. For the ADHD sample, the ADHD diagnosis was confirmed by two board-certified psychiatrists according to DIVA 2.0 (Kooij and Francken, Reference Kooij2010). If comorbid BPD was suspected in ADHD patients, the DIB-R (Zanarini et al., Reference Zanarini, Gunderson, Frankenburg and Chauncey1989) was conducted by a clinical psychologist to assess the comorbidity.

The following comorbidities were excluded from both BPD and ADHD groups according to DSM-5 criteria: major psychiatric disorders with possible influence on impulsive behavior and cognitive functioning, specifically bipolar disorder, major depression, psychotic disorder, addiction; any personality disorder other than BPD in the BPD group; and any personality disorder in ADHD group. The exclusion process was carried out by two board-certified psychiatrists and a clinical psychologist after the interviews and reviewing all aforementioned sources of information about patients.

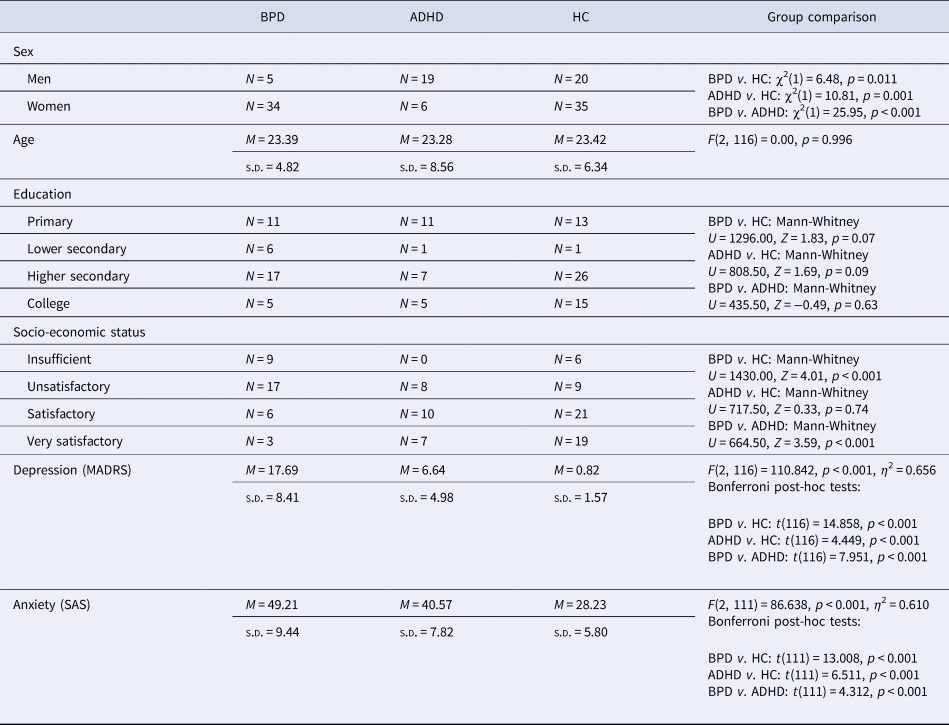

Characteristics of the samples are presented in Table 1. Details on patient status and medications are presented in online Supplementary Material. The groups did not differ in age or level of education. BPD and ADHD groups differed in sex, and both groups also differed in sex in comparison with HC as a result of pooling HC matched to BPD patients and HC matched to ADHD patient into one control sample. BPD patients had lower socioeconomic status than both HC and ADHD patients with no difference between the latter two groups. Large differences between the groups were observed in anxiety and depression symptoms, with BPD patients having the highest scores in both variables and ADHD patients having lower scores in both variables than BPD patients, but higher scores than HC.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of the samples

BPD, borderline personality disorder; ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; HC, healthy controls; MADRS, Montgomery Åsberg Depression Rating Scale; SAS, Zung self-report anxiety scale.

Procedure

All participants completed clinical and behavioral testing carried out by a trained psychologist within one session lasting approximately two hours.

Clinical and behavioral measures

The subjects underwent a test battery consisting of self-reporting and behavioral tests of impulsivity and cognitive function screening consisting of standardized measures in a fixed order (see online Supplementary Material for details). A validated Czech translation of the UPPS-P scale was used (Linhartová et al., Reference Linhartová, Širůček, Barteček, Theiner, Jeřábková, Rudišinová and Kašpárek2017). The UPPS-P has five subscales: lack of premeditation, lack of perseverance, sensation seeking, negative urgency, and positive urgency, with higher scores indicating higher impulsivity. Waiting impulsivity was measured by a Go/NoGo task (GNG), stopping impulsivity by a stop signal task (SST), and impulsive choice by a delay discounting task (DDT) and the Iowa gambling task (IGT). The behavioral tasks were delivered in computerized form, developed in E-Prime 2.0.

Three outcome measures were derived from GNG: NoGo commissions (percentage of NoGo trials erroneously followed by a key press), Go omissions (percentage of Go trials erroneously followed by no key press), and Go reaction time (Go RT; average reaction time on correct Go trials). Stop signal reaction time (SSRT) was derived as the outcome measure from SST by subtracting the average stop signal delay from the average Go RT. The SSRT provides an indication of the average time required for successful stopping; longer SSRTs indicate greater difficulty interrupting actions. Two delayed rewards (DR) were used in DDT: low (approx. 40 EUR) and high (approx. 980 EUR and approx. median salary in the Czech Republic at the time of data collection). Two DRs were chosen so that the influence of DR magnitude could be tested, since discounting becomes steeper in low DRs; in other words, people are less willing to wait if the DR is small (Estle et al., Reference Estle, Green, Myerson and Holt2006; Stanger et al., Reference Stanger, Ryan, Fu, Landes, Jones, Bickel and Budney2012). Area under the curve (AUC; Myerson et al., Reference Myerson, Green and Warusawitharana2001) was used as the main result from DDT (AUC low for the low DR and AUC high for the high DR). The lower the AUC, the steeper the discounting, and the higher the impulsive choice. A computerized version of IGT was used (Odum, Reference Odum2011). The task ended after 200 cards. To track the progress of advantageous decision making, we computed the net score, i.e. the difference between the number of cards drawn from advantageous decks (C + D) and the number of cards drawn from disadvantageous decks (A + B), separately for the first and the second half of the task (1st half net score and 2nd half net score).

Working memory was assessed by the Digit Span subtest from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-III (Wechsler, Reference Wechsler1997) with total score used as the outcome measure. Executive functioning was measured by the Tower of London (ToL), Drexel University, Second Edition (Culbertson and Zillmer, Reference Culbertson and Zillmer2005). Three outcome measures were derived from ToL: move score represents the overall efficiency of the participant's problem solving, initiation time represents the time spent planning before acting, and execution time represents the time needed to solve the task. Attention was assessed by a paper-and-pencil cancellation test d2-R (Brickenkamp et al., Reference Brickenkamp, Schmidt-Atzert, Liepmann, Hoskovcová and Černochová2014). Speed (total number of items worked through) and accuracy (percentage of errors) scores were derived. Unstandardized scores were used in the analyses to preserve the score variability. Further details on the behavioral and cognitive tests are provided in the online Supplementary Material.

Statistical analysis

Differences in UPPS-P (lack of premeditation, lack of perseverance, sensation seeking, negative urgency, and positive urgency), GNG (Go omissions, Go reaction time, and NoGo commissions), SST (stop signal reaction time), digit span (total score), d2 (speed, accuracy), and ToL (move score, initiation time, and execution time) were compared between BPD, ADHD, and HC groups in ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc tests. DDT was analyzed by repeated-measures ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc tests with DR magnitude as a within-subject factor (AUC low, AUC high) and group as a between-subject factor. IGT was analyzed by repeated-measures ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc tests with time as a within-subject factor (net score 1st half, net score 2nd half) and group as a between-subject factor. Moreover, correlations between impulsivity and cognitive and clinical (DIB-R, MADRS, SAS) variables in the three groups were computed. Due to the relatively small sample sizes and the large number of variables, the correlations were not statistically compared between the groups, but significant correlation patterns were examined and commented on.

Results

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics and the results of ANOVAs comparing UPPS-P, GNG, SST, and cognitive tests between the BPD, ADHD, and HC groups. We found that both patient groups as compared to HC have higher lack of premeditation, lack of perseverance, negative urgency, and positive urgency. No group differences were found in sensation seeking. The only significant difference between BPD and ADHD patients was found in negative urgency, with higher scores in BPD patients. In GNG, the ADHD group had significantly more NoGo commissions (i.e. increased waiting impulsivity) than both HC and BPD. The ADHD group also had increased SSRT (i.e. increased stopping impulsivity) as compared to HC and on a trend level as compared to BPD. Regarding the cognitive variables, we found significantly worse performance in working memory in ADHD group as compared to HC and a borderline-significant difference in speed during the attention test, with ADHD having lower speeds than HC. The ADHD group also showed worse performance as compared to HC in executive functions, manifested as higher moves score in ToL.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of dependent variables and results of ANOVAs comparing BPD, ADHD, and HC groups

BPD, borderline personality disorder; ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; HC, healthy controls; PRE, lack of premeditation; PER, lack of perseverance; SS, sensation seeking; NU, negative urgency; PU, positive urgency; Go RT, Go reaction time; SSRT, stop signal reaction time; ToL, Tower of London; init. Time, initiation time; exec. time, execution time; MADRS, Montgomery Åsberg Depression Rating Scale; SAS, Zung self-reported anxiety scale.

Descriptive statistics and results of repeated-measures ANOVA of DDT and IGT are displayed in Table 3 and Fig. 1. In DDT, significant effects of DR magnitude, group, and DR*group interaction were observed. Bonferroni post-hoc tests revealed that in the high DR as compared to low DR condition, all groups exhibited a significant increase in AUC (p < 0.001 for all the three groups). At the same time, HC showed higher AUC in both low DR and high DR conditions (i.e. lower impulsive choice) than either BPD patients (p < 0.001 for both low DR and high DR) or ADHD patients (p = 0.007 for low DR, p < 0.001 for high DR); there was no difference between the patient groups (p = 1.000 for both low and high DR). In IGT, significant effects of time, group, and time*group interaction were observed. Bonferroni post-hoc tests revealed that there were no significant group differences in the net score after the first half of the task (p = 1.000 for all intergroup contrasts). Only HC improved significantly from the first to the second half of the task (p < 0.001); neither of the patient groups did (BPD: p = 0.762; ADHD: p = 0.570). HC had higher net scores in the second half of the task than either BPD patients (p < 0.001) or ADHD patients (p = 0.024) and the two patient groups did not differ (p = 1.000).

Fig. 1. (a) Results of delay discounting for low delayed reward, (b) Results of delay discounting for high delayed reward, (c) Results of Iowa gambling task. Note. (a) Median indifference points from delay discounting with low delayed reward in Czech koruna (CZK; y axis) with delay on x axis per group. (b) Median indifference points from delay discounting with high delayed reward in Czech koruna (y axis) with delay on x axis per group. (c) Boxplots of net scores per groups split for the first and the second half of the task. Net score was computed by counting frequency of cards drawn from the four decks according to the following equation: (C + D) – (A + B). Higher scores indicate more advantageous decision making.*p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics and results of ANOVA for delay discounting and Iowa gambling task

BPD, borderline personality disorder; ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; DDT, delay discounting task; HC, healthy controls; IGT, Iowa gambling task; AUC, area under the curve.

Note. In DDT: delayed reward magnitude is a within-subject factor, group is a between-subject factor. In IGT: time is a within-subject factor (1st half v. 2nd half of the task), group is a between-subject factor.

Relationships between impulsivity and cognitive and clinical variables

Correlation matrices of impulsivity and cognitive and clinical variables are provided in the online Supplementary Materials for the BPD, ADHD, and HC groups separately. The UPPS-P dimensions were generally positively intercorrelated in all the three groups, except sensation seeking (and positive urgency in ADHD), while the behavioral dimensions were generally independent.

In the relationships between impulsivity and cognitive variables, two significant moderate (over r = 0.4) correlations were observed in BPD: a negative correlation between NoGo commissions and initiation time (ToL) and a negative correlation between Go omissions and speed (d2 attention test). A number of significant moderate associations were found in ADHD: a positive correlation between digit span and lack of perseverance and IGT, a positive correlation between initiation time (ToL) and Go omissions and IGT, a positive correlation between move score (ToL) and SSRT, and a positive correlation between accuracy (d2 attention test) and Go RT and DDT. In the relationships between impulsivity and clinical variables, the most prominent pattern was that UPPS-P dimensions (except sensation seeking) were positively correlated with DIB-R in BPD. Moreover, negative and positive urgency showed low to moderate positive associations with MADRS and SAS in ADHD and HC.

Discussion

Self-reported impulsivity

Our results confirm previous research in that both the BPD patients and the ADHD patients, in comparison with HC, manifested increased lack of premeditation, lack of perseverance, and positive and negative urgency. Neither patient group manifested elevated sensation seeking. We found that BPD patients had higher negative urgency than the HC and ADHD groups, with the highest effect size of the intergroup contrast from all impulsivity variables.

The concept of negative urgency combines affective instability and impulsivity, and the importance of this combination for BPD was stressed in previous studies (Tragesser and Robinson, Reference Tragesser and Robinson2009; Sebastian et al., Reference Sebastian, Jacob, Lieb and Tüscher2013; Barteček et al., Reference Barteček, Hořínková, Linhartová and Kašpárek2019). Negative urgency was found to be associated with BPD features in non-clinical samples (Tragesser and Robinson, Reference Tragesser and Robinson2009; DeShong and Kurtz, Reference DeShong and Kurtz2013; Peters et al., Reference Peters, Upton and Baer2013, Reference Peters, Derefinko and Lynam2017), and increased in BPD patients as compared to patients with antisocial personality disorder (Taherifard et al., Reference Taherifard, Abolghasemi and Hajloo2015) and to patients with bipolar disorder (Bøen et al., Reference Bøen, Hummelen, Elvsåshagen, Boye, Andersson, Karterud and Malt2015). Thus, markedly increased negative urgency seems to be specific for BPD patients even in comparison with other impulsive patient groups and constitutes a possible marker for BPD. Comparisons of negative urgency between BPD patients and patients with other impulsive disorders, such as patients with addiction or eating disorders, would be beneficial in future studies.

Negative urgency was found to be associated with self-harm or partner violence (Peters et al., Reference Peters, Upton and Baer2013, Reference Peters, Derefinko and Lynam2017) in non-clinical samples and with suicidal attempts and healthcare utilization in BPD patients (Barteček et al., Reference Barteček, Hořínková, Linhartová and Kašpárek2019). BPD patients show elevated not only negative, but also positive urgency (Bøen et al., Reference Bøen, Hummelen, Elvsåshagen, Boye, Andersson, Karterud and Malt2015; Paret et al., Reference Paret, Hoesterey, Kleindienst and Schmahl2016). Positive urgency was found to be associated with several types of risky behavior in other than BPD samples, such as with substance abuse, compulsive buying, or risky sexual behavior in non-clinical samples (Zapolski et al., Reference Zapolski, Cyders and Smith2009; Rose and Segrist, Reference Rose and Segrist2014; Dinc and Cooper, Reference Dinc and Cooper2015) and with risky behavior in patients with PTSD (Weiss et al., Reference Weiss, Tull, Sullivan, Dixon-Gordon and Gratz2015). In general, positive urgency received less attention than negative urgency in the literature on BPD. This might relate to the fact that negative affect states, but not positive, are related to self-harming and suicidal behavior in BPD. However, BPD patients also experience negative emotions more often than healthy people (Nica and Links, Reference Nica and Links2009; Steenkamp et al., Reference Steenkamp, Suvak, Dickstein, Shea and Litz2015; Law et al., Reference Law, Fleeson, Arnold and Furr2016). In other words, patients with BPD not only tend to act impulsively in intense emotional states, but they also have a higher chance of experiencing intense negative emotional states, in which they are prone to self-harming and life-threatening behavior. This typical pattern seems to be captured by highly elevated negative urgency in BPD patients.

In contrast to the study by Krause-Utz et al. (Reference Krause-Utz, Cackowski, Daffner, Sobanski, Plichta, Bohus, Ende and Schmahl2016), we found no differences in lack of perseverance or lack of premeditation between the patient groups. A possible confounding variable might be sex, which was not equally distributed in the patient groups in our study. Future studies could explore the role of sex in UPPS-P dimensions in BPD and ADHD patients.

Behavioral impulsivity

Our results showed that impulsive action, i.e. both the ability to withhold premature actions (waiting impulsivity) and to stop ongoing actions (stopping impulsivity), is intact in BPD patients; these results are similar to previous studies (under emotionally neutral circumstances; Jacob et al., Reference Jacob, Gutz, Bader, Lieb, Tüscher and Stahl2010; Cackowski et al., Reference Cackowski, Reitz, Ende, Kleindienst, Bohus, Schmahl and Krause-Utz2014; Barker et al., Reference Barker, Romaniuk, Cardinal, Pope, Nicol and Hall2015; Krause-Utz et al., Reference Krause-Utz, Cackowski, Daffner, Sobanski, Plichta, Bohus, Ende and Schmahl2016). Impulsive action was elevated in ADHD patients as compared to HC, similarly as in previous studies (Lampe et al., Reference Lampe, Konrad, Kroener, Fast, Kunert and Herpertz2007; Pani et al., Reference Pani, Menghini, Napolitano, Calcagni, Armando, Sergeant and Vicari2013). We also found close-to-significant differences in both waiting (NoGo commissions) and stopping (SSRT) impulsivity between patients with BPD and ADHD. Thus, the elevation in impulsive action seems to be specific for the ADHD group; and it is not present in patients with BPD.

On the other hand, BPD patients and ADHD patients showed increased impulsive choice in both relevant tasks. As expected, all the three groups showed less steep delay discounting in the high DR condition as compared to low DR condition. In other words, all the participants were willing to wait longer for the delayed reward that had a high value. Both patient groups had steeper delay discounting in both low and high DR conditions than HC did, as in previous studies (Patros et al., Reference Patros, Alderson, Kasper, Tarle, Lea and Hudec2016; Paret et al., Reference Paret, Jennen-Steinmetz and Schmahl2017). In sum, BPD patients, as well as ADHD patients, exhibit a higher preference for immediate rewards than HC regardless of delayed reward magnitude.

In the Iowa gambling task, both patient groups showed less advantageous decision-making than HC, as in previous studies (Toplak et al., Reference Toplak, Jain and Tannock2005; Paret et al., Reference Paret, Jennen-Steinmetz and Schmahl2017), but only after the second half of the task, i.e. after 200 cards. This result was due to the fact that HC improved during the task; the patient groups did not. We administered the prolonged IGT version containing 200 cards since it was previously shown that the standard 100 cards might not be sufficient to learn advantageous decision-making, even in healthy people (Fernie and Tunney, Reference Fernie and Tunney2006). Our data support this hypothesis by showing that a longer time (i.e. 200 cards) was needed to detect group differences between HC and impulsive patients. To sum, both BPD patients and ADHD patients manifested impairment in IGT, indicating a reduced ability to learn from consequences and increased impulsive decision making, but this difference was not shown earlier than after the second half of the prolonged task.

Cognitive functions

The results of cognitive tests in our study are clear: as compared to HC, BPD patients did not show any deficit in cognitive functioning; ADHD patients manifested deficits in attention, working memory, and executive functioning. However, there were no significant differences in the cognitive tests between the two patient groups. This pattern of results is due to the fact that in all the variables with significant differences between the ADHD group and HC, the BPD patients scored on average between the ADHD patients and HC. Our results support studies that excluded ADHD comorbidity and found no attention deficit in BPD patients as compared to HC (Lampe et al., Reference Lampe, Konrad, Kroener, Fast, Kunert and Herpertz2007; Hagenhoff et al., Reference Hagenhoff, Franzen, Koppe, Baer, Scheibel, Sammer, Gallhofer and Lis2013) and lend further support to the hypothesis that the attention deficits in BPD patients observed in some studies might have been driven by ADHD comorbidity. Evidence about deficits of BPD patients in executive functioning remains limited, and our study supports the hypothesis that executive functioning of patients with BPD is usually intact.

However, impaired working memory in BPD patients was previously found in studies that excluded ADHD comorbidity (Stevens et al., Reference Stevens, Burkhardt, Hautzinger, Schwarz and Unckel2004; Hagenhoff et al., Reference Hagenhoff, Franzen, Koppe, Baer, Scheibel, Sammer, Gallhofer and Lis2013). Differences in the literature could be also influenced by the heterogeneity of working memory measures used in the studies. For example, in our study we used a relatively straightforward and short working memory test; both previously mentioned studies used more complex and possibly more demanding tests, like computerized n-back tasks (Stevens et al., Reference Stevens, Burkhardt, Hautzinger, Schwarz and Unckel2004; Hagenhoff et al., Reference Hagenhoff, Franzen, Koppe, Baer, Scheibel, Sammer, Gallhofer and Lis2013). It is possible that BPD patients without ADHD comorbidity could show some cognitive impairment only in highly demanding situations. It is also possible that highly demanding tasks could induce stress levels that influence the cognitive performance of BPD patients, similarly as high stress levels were found to increase impulsive action in BPD (Krause-Utz et al., Reference Krause-Utz, Cackowski, Daffner, Sobanski, Plichta, Bohus, Ende and Schmahl2016). Future studies should explore the question of whether BPD patients fail in highly demanding working memory tasks as compared to less demanding tasks and, if such impairment was found, whether it could have been caused by higher stress levels during demanding tasks as opposed to insufficient cognitive function capacity.

More support for the importance of emotions in cognitive functioning in BPD can be drawn from the perspective of comparison between performances in ToL and IGT. ToL can be considered a measure of ‘cool’, i.e. emotionally neutral, executive functioning requiring predominantly cognitive planning and correct execution of the plan (Chan et al., Reference Chan, Shum, Toulopoulou and Chen2008). On the other hand, IGT can be considered a measure of ‘hot’ executive functions that include an emotional aspect by providing a rewards and punishments (gains and losses) environment (Chan et al., Reference Chan, Shum, Toulopoulou and Chen2008). Importantly, BPD patients showed impairment only in IGT, but their decision-making was intact in ToL.

Relationships between impulsivity and cognitive and clinical variables

Our study confirms the results of the previous studies (MacKillop et al., Reference MacKillop, Weafer, Gray, Oshri, Palmer and de Wit2016; Linhartová et al., Reference Linhartová, Širůček, Ejova, Barteček, Theiner and Kašpárek2019) in that dimensions of self-reported impulsivity are related, while low to very low correlations are present between behavioral tests of impulsivity. Worse performance in attention and working memory was associated with higher impulsive choice, and worse performance in executive functioning was associated with higher stopping impulsivity and higher impulsive choice in patients with ADHD. Similar associations were not present in patients with BPD or in HC. The results indicate that impulsivity in ADHD is more closely linked with cognitive functions than in BPD.

Importantly, we found moderate positive correlations of BPD severity with all the UPPS-P subscales except sensation seeking. BPD severity was not correlated with any other variable including depression and anxiety symptoms. This result puts more emphasis on the importance of impulsivity for BPD patients.

Limitations

The differences in sex and inpatient/outpatient status between the BPD and ADHD samples can be considered as a limitation of our study. However, our sample has high ecological validity, since there is a prevalence of women among BPD patients and a prevalence of men among ADHD patients in clinical samples (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Both sex and inpatient/outpatient status influence could not have been tested, since the vast majority of the BPD patients were women and inpatients, and the majority of the ADHD patients were men and all the ADHD patients were outpatients. However, we acknowledged the state severity of the patients by measuring depression and anxiety symptom levels. It can be viewed as a possible limitation that a single pooled sample of healthy controls was used for comparison with the patient groups. However, this approach was chosen to strengthen the statistical power of the analyses and to enable direct comparison of the two patient groups within ANOVA. Further, the influence of several possible confounding variables on impulsivity, specifically depression and anxiety symptoms, could not have been tested directly in the linear models due to small sample sizes for such a complex analysis. However, we included depression and anxiety in the correlation analysis to track a possible interrelatedness with impulsivity or cognitive measures. The differences between the groups in correlations were not statistically tested due to the high number of variables included in this analysis. Thus, the results should be interpreted carefully and should serve as hypotheses-generating rather than definite results.

Conclusion

Comprehensive analysis of impulsivity measures showed that the major diagnostically specific contributor to impulsive behavior in patients with BPD is negative urgency. BPD patients, unlike ADHD patients, do not show impairments in impulsive action and their cognitive functions seem to be intact. Thus, it is crucial to distinguish the ADHD comorbidity in BPD samples.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291719001892.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Anne Johnson for English-language editing.

Financial support

This work was funded by the Ministry of Health of the Czech Republic grant no. 15-30062A, by the Ministry of Health of the Czech Republic – Conceptual Development of Research Organization (‘FNBr, 65269705’), and by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic – Specific University Research project no. MUNI/A/1469/2018.

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.