Introduction

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by a dysfunctional pattern of inattention, hyperactivity, or impulsivity, leading to negative outcomes in social, academic and occupational contexts throughout an individual's life (APA, 2013; Barbaresi et al. Reference Barbaresi, Colligan, Weaver, Voigt, Killian and Katusic2013; Dalsgaard et al. Reference Dalsgaard, Østergaard, Leckman, Mortensen and Pedersen2015). Although the persistence of ADHD into adulthood has been well documented (Faraone et al. Reference Faraone, Asherson, Banaschewski, Biederman, Buitelaar, Ramos-Quiroga, Rohde, Sonuga-Barke, Tannock and Franke2015; Asherson et al. Reference Asherson, Buitelaar, Faraone and Rohde2016; Thapar & Cooper, Reference Thapar and Cooper2016), uncertainties remain regarding how well current diagnostic criteria capture the complexity of the adult form of the disorder (WHO, 1992; Matte et al. Reference Matte, Rohde and Grevet2012; APA, 2013; Hartung et al. Reference Hartung, Lefler, Canu, Stevens, Jaconis, LaCount, Shelton, Leopold and Willcutt2016). Due to ADHD's broad definition, the most widely used set of criteria, in clinical and research settings, is that from the American Psychiatric Association's (APA) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) (APA, 2013; Thapar & Cooper, Reference Thapar and Cooper2016). Studies testing the performance of different versions of DSM have shown that their psychometric and diagnostic properties may vary depending on the set of criteria used and on the socio-demographic characteristics of the assessed population (Polanczyk et al. Reference Polanczyk, de Lima, Horta, Biederman and Rohde2007; Bauermeister et al. Reference Bauermeister, Canino, Polanczyk and Rohde2010). Based on data demonstrating that ADHD can have its onset after the age of 7 years (Kieling et al. Reference Kieling, Kieling, Rohde, Frick, Moffitt, Nigg, Tannock and Castellanos2010), and also on the age-dependent decline of symptoms (Faraone et al. Reference Faraone, Biederman and Mick2006), as well as the appropriateness of a lower threshold for adult diagnosis (Kooij et al. Reference Kooij, Buitelaar, van den Oord, Furer, Rijnders and Hodiamont2005), DSM-5 brought a modified set of criteria presenting a lower five-symptom threshold for adults and an extended limit for the age of onset to 12 years (APA, 2013). Despite evident advances in terms of phenomenological description, concerns have been raised regarding how well these modifications reflect adult ADHD phenotype and what would be its effects on prevalence (Batstra & Frances, Reference Batstra and Frances2012).

In terms of symptom structure, the versions of DSM ADHD criteria have oscillated from single-dimensional structures to tri-dimensional structures comprised of inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity symptoms (APA, 1980, 1987, 1994, 2000). In adults, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) of DSM-IV symptoms revealed a latent structure consisting of a general factor with two or three specific factors, with older individuals being prone to demonstrate separate hyperactivity and impulsivity (Gomez et al. Reference Gomez, Vance and Gomez2013; Morin et al. Reference Morin, Tran and Caci2016). For DSM-5, a latent structure with one general and two specific factors was observed (Matte et al. Reference Matte, Anselmi, Salum, Kieling, Gonçalves, Menezes, Grevet and Rohde2015a ). Regarding symptoms and impairment, studies in adults using DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria demonstrated that symptoms from the inattentive dimension were the symptoms most associated with impairment in the adult population (Barkley et al. Reference Barkley, Murphy and Fischer2008; Das et al. Reference Das, Cherbuin, Butterworth, Anstey and Easteal2012; Matte et al. Reference Matte, Rohde and Grevet2012, Reference Matte, Anselmi, Salum, Kieling, Gonçalves, Menezes, Grevet and Rohde2015a ), with ‘difficulty sustaining attention’, ‘easily distracted’ and ‘difficulty in organizing tasks’ presenting the strongest association with impairment (Matte et al. Reference Matte, Anselmi, Salum, Kieling, Gonçalves, Menezes, Grevet and Rohde2015a ). Furthermore, there is scarce and conflicting information regarding the relationship between ADHD symptoms and co-morbidities, most likely as a result of differences in populations evaluated. In one population sample, DSM-IV ADHD symptoms demonstrated good discriminant validity, except for ‘difficulty to sustain attention’ that was also associated with anxiety disorders (Kessler et al. Reference Kessler, Green, Adler, Barkley, Chatterji, Faraone, Finkelman, Greenhill, Gruber, Jewell, Russo, Sampson and Van Brunt2010). On the other hand, sixteen out of the eighteen symptoms from DSM-5 ADHD criteria were associated with both ADHD diagnosis and several co-morbidities in a clinical sample (Matte et al. Reference Matte, Rohde, Turner, Fisher, Shen, Bau, Nigg and Grevet2015b ).

Regarding prevalence, studies applying the DSM-IV criteria observed rates ranging from 1.0% to 4.4% (Kooij et al. Reference Kooij, Buitelaar, van den Oord, Furer, Rijnders and Hodiamont2005; Medina et al. Reference Medina-Mora, Borges, Lara, Benjet, Blanco, Fleiz, Villatoro, Rojas and Zambrano2005; Kessler et al. Reference Kessler, Adler, Barkley, Biederman, Conners, Demler, Faraone, Greenhill, Howes, Secnik, Spencer, Ustun, Walters and Zaslavsky2006; Fayyad et al. Reference Fayyad, De Graaf, Kessler, Alonso, Angermeyer, Demyttenaere, De Girolamo, Haro, Karam, Lara, Lépine, Ormel, Posada-Villa, Zaslavsky and Jin2007; Bitter et al. Reference Bitter, Simon, Bálint, Mészáros and Czobor2010; Michielsen et al. Reference Michielsen, Semeijn, Comijs, van de Ven, Beekman, Deeg and Kooij2012; Tuithof et al. Reference Tuithof, Ten Have, van Dorsselaer and de Graaf2014), and two meta-analyses estimated the DSM-IV adult prevalence as 2.5% and 5.0% (Simon et al. Reference Simon, Czobor, Bálint, Mészáros and Bitter2009; Willcutt, Reference Willcutt2012). Recently, Matte et al. (Reference Matte, Anselmi, Salum, Kieling, Gonçalves, Menezes, Grevet and Rohde2015a ) evaluated the impact in ADHD prevalence due to use of DSM-IV v. DSM-5 criteria in a cross-sectional evaluation of a population-based sample of young adults, demonstrating that when applying the DSM-5 criteria there was a 30% increase in prevalence from 2.8% to 3.5%. However, three recent follow-up studies have demonstrated that around 90% of adults with a current pervasive and impairing ADHD syndrome did not have childhood ADHD or childhood ADHD symptoms (Moffitt et al. Reference Moffitt, Houts, Asherson, Belsky, Corcoran, Hammerle, Harrington, Hogan, Meier, Polanczyk, Poulton, Ramrakha, Sugden, Williams, Rohde and Caspi2015; Agnew-Blais et al. Reference Agnew-Blais, Polanczyk, Danese, Wertz, Moffitt and Arseneault2016; Caye et al. Reference Caye, Rocha, Anselmi, Murray, Menezes, Barros, Gonçalves, Wehrmeister, Jensen, Steinhausen, Swanson, Kieling and Rohde2016). Thus, the need for estimating the prevalence for adult ADHD without childhood onset criterion has gained clinical and epidemiological relevance, since the adult ADHD prevalence would increase considering those individuals. For example, there is an enormous discrepancy between the 3.5% rate for the full DSM-5 ADHD and the 12.5% rate for the DSM-5 ADHD when disregarding the age-of-onset (AoO) criterion, both estimated in the same sample by Caye et al. (Reference Caye, Rocha, Anselmi, Murray, Menezes, Barros, Gonçalves, Wehrmeister, Jensen, Steinhausen, Swanson, Kieling and Rohde2016). These results have challenged the classical neurodevelopmental definition of ADHD, as well as the validity of the AoO criterion. Thus, there is a need for further information on the prevalence of ADHD considering these two different ADHD definitions (Faraone & Biederman, Reference Faraone and Biederman2016), in populations beyond late adolescence and early adulthood.

Taking into account this scenario, our study aims to extend the characterization of DSM-5 ADHD in a representative population-based sample of 30-year-old individuals, in which the foremost changes in brain structure and functioning have occurred (Tau & Peterson, Reference Tau and Peterson2010; Cao et al. Reference Cao, Huang, Peng, Dong and He2016). Our specific objectives are to assess: (a) the best structural model for ADHD symptoms in this population (construct validity); (b) the performance of specific ADHD symptoms and the best symptomatic cut-off in predicting impairment (construct and discriminant validity respectively); (c) the specificity of DSM-5 ADHD symptoms to the disorder (discriminant validity); (d) the prevalence rate of ADHD according to the DSM-5 criteria; (e) variations in the ADHD prevalence rates, exploring modifications and deletions of some DSM-5 criteria with special attention to the age of onset during childhood criterion.

Method

Study design and sample

This is a cross-sectional study assessing 30-year-old adults from the 1982 Pelotas Birth Cohort Study. The cohort is comprised of all live born infants from the year 1982 (n = 5914) in Pelotas, a city of 333 000 inhabitants in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. From the original sample, 3701 individuals were reassessed in 2012. These 3701 individuals plus the 325 who died before 2012 represent a 68.1% retention rate (n = 4026). The present study was carried out with the 3574 subjects screened for ADHD. The Institutional Review Board of the Federal University of Pelotas approved the study, and written informed consent was obtained from all subjects. For more information about the 1982 Pelotas Cohort Study, see Horta et al. (Reference Horta, Gigante, Gonçalves, dos Santos Motta, Loret de Mola, Oliveira, Barros and Victora2015).

Psychiatric assessment

In face-to-face interviews, trained psychologists applied a diagnostic evaluation including ADHD screening to 3574 individuals. This initial screening was based on the World Health Organization Adult ADHD Self-report Scale (ASRS; Kessler et al. Reference Kessler, Adler, Ames, Demler, Faraone, Hiripi, Howes, Jin, Secnik, Spencer, Ustun and Walters2005) comprising four inattention items (‘does not follow through’, ‘difficulty organizing tasks’, ‘forgetful’, and ‘reluctant to engage in mental tasks’), and two hyperactivity items (‘fidgets’ and ‘always on the go’). We adapted the wording of the instrument to reflect adult DSM-5 symptoms. The proposed ASRS cut-off of four symptoms demonstrated 68.7% sensitivity, 99.5% specificity and 97.9% accuracy to detect ADHD cases in an adult population (Kessler et al. Reference Kessler, Adler, Ames, Demler, Faraone, Hiripi, Howes, Jin, Secnik, Spencer, Ustun and Walters2005). In order to achieve higher sensitivity, a cut-off of two symptoms was applied and those with less than two symptoms were considered negative for ADHD diagnosis.

Individuals positively screened (n = 724, 20.3% of total sample) responded to the questions for the remaining DSM-5 ADHD symptoms and criteria (APA, 2013) through a structured interview (see Matte et al. Reference Matte, Anselmi, Salum, Kieling, Gonçalves, Menezes, Grevet and Rohde2015a ). The interviews addressed the twelve lasting inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms not addressed by the initial screener (criterion A), and questions on the age of onset before the age of 12 years (criterion B), symptom pervasiveness (criterion C), and impairment (criterion D).

The presence of a persistent pattern of inattention and/or hyperactivity/impulsivity in the last 6 months was investigated. To assess age of onset, interviewers asked about the presence of several ADHD symptoms before the age of 12 (in previous waves, the 1982 Pelotas Birth Cohort did not collect information on ADHD). To assess symptom pervasiveness, subjects responded whether they had several symptoms interfering in at least two of three different settings – home, social and work/academic – in the last 6 months. To assess impairment, the following question was asked: ‘How much trouble have symptoms of inattention or hyperactivity/impulsivity caused in your life?’. Four possible answers were available for this question: ‘none’, ‘some’, ‘a lot’ or ‘very much’. Criterion D was considered positive when individuals answered ‘a lot’ or ‘very much’.

To assess frequently associated ADHD co-morbidities, we applied modified modules for general anxiety disorder (GAD), social phobia, major depression (MD) and bipolar disorder (BD) based on the Portuguese version of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI; Amorim, Reference Amorim2003). The MINI presents kappa values of 0.65–0.85 (sensitivity 0.75–0.92, specificity 0.90–0.99) for the Brazilian population at primary-care settings (Marques & Zuardi, Reference Marques and Zuardi2008). From the 724 positively screened individuals, 519 individuals had the complete information for all the assessed variables.

Determining symptom factor structure

To determine the symptom factor structure, we performed a CFA on the 18 DSM-5 ADHD symptoms to identify the underlying model that best fits the latent-factor structure, testing for the following: (1) one-factor model (ADHD); (2) correlated two-factor model (inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity); (3) correlated three-factor model (inattention, hyperactivity, impulsivity); (4) bifactor model with one general and two specific factors (inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity); and (5) bifactor model with one general and three specific factors (inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity – a non-orthogonal model in which hyperactivity and impulsivity factors are allowed to correlate). Information obtained from 519 individuals was used to determine the factor structure.

Evaluating the association between ADHD symptoms and clinical impairment

A three-step analysis was utilized to determine the individual ADHD symptoms most associated with moderate or severe impairment. The analysis was based on the methods used in studies by Kessler et al. (Reference Kessler, Green, Adler, Barkley, Chatterji, Faraone, Finkelman, Greenhill, Gruber, Jewell, Russo, Sampson and Van Brunt2010) and Matte et al. (Reference Matte, Anselmi, Salum, Kieling, Gonçalves, Menezes, Grevet and Rohde2015a ).

In the first step, we performed a bivariate association analysis using χ2 tests to assess the relationship between symptoms and clinical impairment. The eighteen DSM-5 symptoms were ranked using their respective unadjusted odds ratios. In the second step, a binary stepwise logistic regression model was performed, with impairment as the dependent variable and the eighteen ADHD symptoms as the independent variables, in order to identify symptoms independently associated with impairment after controlling for all other ADHD symptoms. Since conventional stepwise regression analysis might select a suboptimal subset of symptoms associated with impairment due to minor differences in bivariate associations, we performed further analyses. In the third step, all possible subsets (APS) logistic regression analysis indicated the best set of symptoms predicting clinical impairment. APS analysis establishes all possible sets of symptoms associated with impairment when taking into account a pre-established maximum number of symptoms to be included per set (i.e. symptom or group of symptoms associated with impairment, with a maximum number of symptoms per set pre-established by binary stepwise logistic regression). APS also ranks subsets according to their association with the outcome using χ2 values as the ranking criterion. Information gathered from individuals with complete data was used in this analysis.

Evaluating the association between ADHD symptoms and co-morbidities

To assess whether DSM-5 ADHD symptoms are specific to ADHD or relate to other psychiatric disorders, we used a binary stepwise logistic regression model to identify which symptoms were independently associated with each of the co-morbidities assessed after controlling for ADHD status and all other ADHD symptoms. Significant odds ratios for the associations between symptom and co-morbidities would suggest that the symptom is not specific for ADHD. Non-missing data sample was used in the analysis.

Evaluating the best symptom cut-off for diagnosis

In order to evaluate the best symptom cut-off, we tested for the minimum number of symptoms that allowed for the separation of those subjects with moderate or severe impairment from those with mild or no impairment due to ADHD symptoms using receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) analysis. This analysis determines the best cut-off for inattention or hyperactivity/impulsivity dimensions taking into account the best balance between sensitivity and specificity. We also calculated Youden's J index using the formula J = sensitivity + specificity – 1 (Ruopp et al. Reference Ruopp, Perkins, Whitcomb and Schisterman2008). Youden's J index provides a score ranging from 0 to 1 summarizing the performance of a diagnostic test. A value of zero indicates the test gives the same proportion of positive diagnosis in groups with and without disease. A value of one indicates a perfect diagnostic property without false-positive or false-negative results.

ADHD prevalence estimations

DSM-5 ADHD prevalence was estimated for the entire screened sample (n = 3574), including 205 individuals with some missing data. From these 205 individuals, it was possible to determine ADHD status for 118 individuals who had the presence of at least five symptoms in at least one of the ADHD dimensions despite missing data for one or more symptoms. For 87 individuals, it was still possible to impute ADHD status based on their six-symptom ASRS-based screener's profile.

We also calculated ADHD prevalence rates based on six different scenarios: (1) depending solely on different symptomatic thresholds for inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms (criterion A); (2) different symptomatic thresholds plus the presence of ADHD symptoms before the age of 12 (criterion B); (3) different symptomatic thresholds plus the presence of symptoms in at least two contexts (criterion C); (4) different symptomatic thresholds plus moderate or severe impairment due to ADHD symptoms (criterion D); (5) for adult ADHD without considering childhood onset, applying criterion A + C + D, but without applying criterion B (age of onset); and (6) for full DSM-5 adult ADHD. We also calculated DSM-5 current presentation rates for inattentive, hyperactive/impulsive and combined subtypes. For this analysis, we used information from 3369 individuals without missing data.

Performing and setting the statistical analyses

A significance level of 5% and two-tailed tests were used when appropriate. APS analysis was performed with R-project (‘leaps’ package) (R Core Team, 2013), ROC analysis with Stata (StataCorp., 2013), CFA with Mplus version 7.0 (Muthén & Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén2012) and all others using SPSS version 18 (SPSS Inc. 2009).

Results

Description of the sample

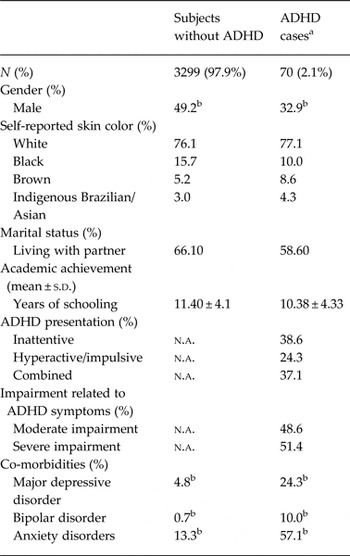

ADHD and non-ADHD groups did not differ in terms of skin color, years of schooling, or marital status. Women represented 67.1% of ADHD cases. This predominance of the female gender remained the same even when applying different symptom cut-offs (p = 0.95). Subjects with ADHD presented significantly higher rates of all co-morbid disorders evaluated (Table 1).

Table 1. Sociodemographic profile and co-morbidity data on DSM-5 attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) cases and subjects without ADHD (n = 3369)

n.a., Not applicable.

a ADHD cases = subjects with at least 5/9 inattention and/or 5/9 hyperactivity symptoms + symptom onset before age 12 + symptoms in more than one setting + moderate or severe impairment related to ADHD symptoms.

b Statistical difference between ADHD and non-ADHD groups (p < 0.05).

Assessing the factor structure of ADHD symptoms

The latent structure underlying the eighteen ADHD symptoms was best captured by the bifactor model with one general and three specific factors, showing marginally acceptable fit indexes [RMSEA = 0.050, 90% confidence interval (CI) 0.042–0.058, CFI = 0.891, TLI = 0.856, WRMR = 1.164]. A closer inspection of factor loadings and reliability indexes revealed that the general factor is mostly related to inattention symptoms. The specific hyperactivity and impulsivity factors are also reliable for adults, but with lower impact on the general latent trait (Supplementary Table S1).

Association between ADHD symptoms and clinical impairment

According to an unadjusted odds ratio rank, the five highest ranked symptoms associated with impairment were from the inattentive dimension. Of the eighteen ADHD symptoms, seven were independent predictors of impairment. Of these seven symptoms, five were from the inattentive dimension (‘difficulty sustaining attention’, ‘does not seem to listen’, ‘does not follow through’, ‘reluctant to engage in mental tasks’ and ‘loses things’), one was from the hyperactive dimension (‘leaves seat’) and one was from the impulsivity dimension (‘blurts out answers’). The APS analysis using a maximum of seven symptoms per subset revealed that five inattention symptoms (‘does not seem to listen’, ‘does not follow through’, ‘loses things’, ‘easily distracted’ and ‘forgetful’) and one hyperactivity/impulsivity symptom (‘difficulty waiting his/her turn’) were present in all ten of the highest ranked subsets of symptoms that best predicted impairment (Table 2).

Table 2. Association of individual DSM-5 attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms with impairment from ADHD and with co-morbidities (n = 519)

OR, Odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; APS, all possible subsets; n.s., non-significant association between ADHD symptom and clinical impairment.

These analyses were performed only for the 519 subjects who screened positive for ADHD (at least two positive screening questions) and provided information on all 18 ADHD symptoms.

a Unadjusted ORs from χ2 test.

b Adjusted ORs from conventional binary regression.

Association between ADHD symptoms and co-morbidities

Five symptoms were independently associated with ADHD-related impairment but not with co-morbidities: ‘difficulty sustaining attention’, ‘does not seem to listen’, ‘loses objects’, ‘leaves seat’ and ‘blurts out answers’. Two symptoms were associated with both ADHD and co-morbidities: ‘Does not follow through’ with social phobia and GAD; ‘reluctant to engage in mental task’ with BD and GAD. Still, two symptoms were independently associated with co-morbidities but not with ADHD: ‘forgetful’ with BD and ‘difficulty waiting his/her turn’ with social phobia. Among the symptoms specifically associated only with ADHD, ‘does not seem to listen’ and ‘loses objects’ were present also in the ten highest ranked sets of APS. In Table 2, we presented the OR for the association between ADHD symptoms and co-morbidities.

Best symptom cut-off predicting ADHD

Four symptoms of inattention or hyperactivity/impulsivity constituted the best symptom cut-off predicting moderate or severe ADHD-related impairment. When considering individuals presenting at least moderate impairment, the cut-off of four inattention symptoms presented a sensitivity of 71% and specificity of 59%, an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.72 (95% CI 0.70–0.74) and a Youden's J index of 0.30. When considering those with severe impairment, the four inattention symptoms cut-off presented a Youden's J index of 0.40. For the four hyperactive/impulsive symptom cut-off considering individuals with at least moderate impairment, sensitivity was 49% and specificity was 60%, with an AUC of 0.56 (95% CI 0.53–0.59), and a Youden's J index of 0.09. When considering severe impairment, the Youden's J index increased to 0.12.

Prevalence estimates

DSM-5 adult ADHD prevalence was 2.1% (95% CI 1.6–2.5) considering subjects with complete data (n = 3369) and 2.4% (95% CI 1.9–2.9) when imputation for missing data was used (n = 3574). Prevalence rate for ADHD without AoO criterion was 5.8% (n = 3369) (95% CI 5.03–6.60). Prevalence rates for DSM-5 adult ADHD subtypes were 38.6% for inattentive, 24.3% for hyperactive-impulsive, and 37.1% for their combination (Tables 1 and 3).

Table 3. Prevalence (95% CI) of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) across several symptom cut-offs and differential application of ADHD criteria (n = 3369)

Inat, Inattention; hyper, hyperactivity; imp, impulsivity.

Patients included in the first row were counted again in the subsequent rows, if they continue reaching the progressively higher cut-offs.

Each row is less inclusive than the others below.

aImpairment related to ADHD symptoms.

Discussion

This is study is the first to assess psychometric properties and population prevalence considering DSM-5 ADHD criteria in individuals beyond the transition from adolescence to adulthood. Our results demonstrated that the best model fitting with DSM-5 symptom latent structure is the bifactor model with one general and three specific factors. Inattention symptoms were more associated with impairment than hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms. The best symptomatic threshold for adult ADHD diagnosis was four, but the performance of this threshold in predicting impairment was far from being optimal. Applying the DSM-5 adult ADHD criteria, prevalence was 2.1%. However, if considering only adult ADHD independently of childhood onset of symptoms (i.e. counting individuals with a pervasive persistent pattern of current symptoms causing impairment), prevalence rate increases to 5.8%.

Regarding symptoms structure, our results are in accordance with previous studies for DSM-IV and DSM-5 latent structure in adults showing that the adult ADHD phenotype is constituted mainly by inattentive symptoms, but poorly by hyperactive/impulsive symptoms (Gibbins et al. Reference Gibbins, Toplak, Flora, Weiss and Tannock2012; Gomez et al. Reference Gomez, Vance and Gomez2013; Matte et al. Reference Matte, Anselmi, Salum, Kieling, Gonçalves, Menezes, Grevet and Rohde2015a ; Morin et al. Reference Morin, Tran and Caci2016). Considering the specific factors, our results are in line with Morin et al. (Reference Morin, Tran and Caci2016) as they show a three specific factor structure (separating inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity) and differing from three other studies that demonstrated a better fit with two specific factors (Gibbins et al. Reference Gibbins, Toplak, Flora, Weiss and Tannock2012; Gomez et al. Reference Gomez, Vance and Gomez2013; Matte et al. Reference Matte, Anselmi, Salum, Kieling, Gonçalves, Menezes, Grevet and Rohde2015a ). According to Morin et al. (Reference Morin, Tran and Caci2016), the age of population accounts for differences observed on symptom factorial structure as ADHD phenotype evolves over time. Moreover, the separation of hyperactivity and impulsivity factors could be the consequence of a more reliable measurement of impulsivity symptoms in older adults than in younger populations (Wagner et al. Reference Wagner, Martel, Cogo-Moreira, Maia, Pan, Rohde and Salum2016). Reinforcing these two hypotheses, our results showed a difference between the three specific factors found in the 30-year-old sample (1982 Pelotas Cohort) and the two specific factors observed in the 18- to 19-year-old sample (1993 Pelotas Cohort) (Matte et al. Reference Matte, Anselmi, Salum, Kieling, Gonçalves, Menezes, Grevet and Rohde2015a ).

Furthermore, the regression analyses demonstrated that the symptoms from the inattentive dimension were more associated with impairment than hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms, in line with previous reports for DSM-IV (Barkley et al. Reference Barkley, Murphy and Fischer2008; Das et al. Reference Das, Cherbuin, Butterworth, Anstey and Easteal2012). We observed similar findings in comparison to Matte et al. (Reference Matte, Anselmi, Salum, Kieling, Gonçalves, Menezes, Grevet and Rohde2015a ) results on DSM-5 criteria regarding the importance of DSM-5 inattention symptoms determining impairment. However, unlike the Matte et al. (Reference Matte, Anselmi, Salum, Kieling, Gonçalves, Menezes, Grevet and Rohde2015a ) findings showing that symptoms most strongly associated with impairment in the younger cohort were those related to executive dysfunctions (‘difficulty sustaining attention’, ‘easily distracted’ and ‘difficulty in organizing task’), in our sample were those symptoms related to the consequences of inattention (‘does not seem to listen’, ‘does not follow through’ and ‘loses things’). Taken together, these results challenge the construct validity for the hyperactive/impulsive symptoms in adults. Regarding the nosological specificity of each symptom for ADHD, four out of eighteen symptoms were associated with co-morbidities: ‘does not follow through’ was associated with social phobia and GAD, ‘reluctant to engage in mental tasks’ was associated with bipolar disorder and GAD, ‘forgetful’ was associated with bipolar disorder, and ‘difficulty waiting your turn’ was associated with social phobia. Surprisingly, two symptoms were associated with co-morbidities but not with ADHD (‘forgetful’ with BD and ‘difficulty waiting his/her turn’ with social phobia). These results on the discriminant validity for individual symptoms are more in accordance with DSM-5 data derived from clinical samples (Matte et al. Reference Matte, Rohde, Turner, Fisher, Shen, Bau, Nigg and Grevet2015b ) than with DSM-IV population findings (Kessler et al. Reference Kessler, Green, Adler, Barkley, Chatterji, Faraone, Finkelman, Greenhill, Gruber, Jewell, Russo, Sampson and Van Brunt2010). Thus, our CFA and regressions findings showed that each ADHD symptoms present a potential differential construct and discriminant properties (Supplementary material; Table S1).

In terms of the minimum number of symptoms necessary for diagnosis, our results demonstrated that a cutoff of four symptoms was more appropriate than the five symptom cutoff proposed by the DSM-5 criteria (APA, 2013). This result is in accordance with Kooij et al. (Reference Kooij, Buitelaar, van den Oord, Furer, Rijnders and Hodiamont2005) for DSM-IV criteria in adults and different from the Matte et al. (Reference Matte, Anselmi, Salum, Kieling, Gonçalves, Menezes, Grevet and Rohde2015a ) findings on DSM-5 criteria showing that the best cut-off was five. Still, inattention symptoms best performed discriminating cases from non-ADHD subjects, but with a poor to moderate capacity in detecting cases (sensitivity 71%, specificity 59%, Youden's J index = 0.30). In addition, hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms showed very poor discriminant validity (sensitivity 49%, specificity 60%, Youden's J index = 0.09). These results demonstrated that a dimensional approach based in symptoms counting could not be reliable. In addition, gathering the results from the ROC analysis and those demonstrating the weak role of hyperactivity on determining ADHD-related impairment may suggest discriminant validity caveats in current diagnostic criteria.

Regarding DSM-5 ADHD prevalence, the 2.1% rate is similar to rates found by previous studies in adult populations for both DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria and it does not represent an explosion in prevalence as predicted by some authors (Batstra & Frances, Reference Batstra and Frances2012). In spite of this, the 2.1% represents a 31% increase in prevalence when compared to the 1.2% rate that would have been obtained if the six symptoms cut-off proposed by DSM-IV had been used. Furthermore, the marked difference of 1.4% in prevalence observed between our rate (2.1%) and the 3.5% rate detected by Matte et al. (Reference Matte, Anselmi, Salum, Kieling, Gonçalves, Menezes, Grevet and Rohde2015a ) (both data derived from the assessment of individuals from the same city, but at different ages) may reflect the age-dependent decline on the ADHD trait in population (Faraone et al. Reference Faraone, Biederman and Mick2006). Still, prevalence rises almost threefold (5.8%) if counting individuals presenting a pervasive and persistent ADHD syndrome, but without endorsing the AoO criterion. The detection of this group of individuals and its phenotypic characterization represent a new challenge in epidemiologic terms, since recent findings showed that ADHD could have its onset in late adolescence or even during young adulthood in a substantial number of individuals from population (Moffitt et al. Reference Moffitt, Houts, Asherson, Belsky, Corcoran, Hammerle, Harrington, Hogan, Meier, Polanczyk, Poulton, Ramrakha, Sugden, Williams, Rohde and Caspi2015; Agnew-Blais et al. Reference Agnew-Blais, Polanczyk, Danese, Wertz, Moffitt and Arseneault2016; Caye et al. Reference Caye, Rocha, Anselmi, Murray, Menezes, Barros, Gonçalves, Wehrmeister, Jensen, Steinhausen, Swanson, Kieling and Rohde2016).

Interestingly, adult ADHD individuals were predominantly female in a 2:1 ratio. This finding is in accordance with previous population studies (Kooij et al. Reference Kooij, Buitelaar, van den Oord, Furer, Rijnders and Hodiamont2005; Matte et al. Reference Matte, Anselmi, Salum, Kieling, Gonçalves, Menezes, Grevet and Rohde2015a ), but different from Kessler et al. (Reference Kessler, Adler, Barkley, Biederman, Conners, Demler, Faraone, Greenhill, Howes, Secnik, Spencer, Ustun, Walters and Zaslavsky2006); Fayyad et al. (Reference Fayyad, De Graaf, Kessler, Alonso, Angermeyer, Demyttenaere, De Girolamo, Haro, Karam, Lara, Lépine, Ormel, Posada-Villa, Zaslavsky and Jin2007) and Moffitt et al. (Reference Moffitt, Houts, Asherson, Belsky, Corcoran, Hammerle, Harrington, Hogan, Meier, Polanczyk, Poulton, Ramrakha, Sugden, Williams, Rohde and Caspi2015). According to Kooij et al. (Reference Kooij, Buitelaar, van den Oord, Furer, Rijnders and Hodiamont2005), the preponderance of females in their study could be the consequence of applying a lower symptom cut-off which is suggested to be more sensitive for the female ADHD phenotype. However, when we tested different symptom cut-offs, female:male ratios did not change, suggesting a preponderance of women in adult ADHD cases (data available upon request).

Some limitations must be taken into account while interpreting the results of this study. The 1982 Pelotas Birth Cohort Study presented a 32% rate of attrition in the 2012 wave, with a higher proportion of retained women than men (71% v. 65%). Thus, the results obtained may represent biased estimations. However, the retention rate in our study was similar to that observed in cohorts from high-income countries at the same age and was higher than rates observed in cohorts from low-income countries (Horta et al. Reference Horta, Gigante, Gonçalves, dos Santos Motta, Loret de Mola, Oliveira, Barros and Victora2015). In addition, data from a 30-year-old cohort retaining more than 68% of the original sample can still be considered representative of the original sample (see Horta et al. Reference Horta, Gigante, Gonçalves, dos Santos Motta, Loret de Mola, Oliveira, Barros and Victora2015). The preponderance of females with ADHD could be accounted for by differences in the female:male retention rates at follow-up. However, this factor could not be pivotal, since the female:male ratio for the whole reassessed sample was 1.03 and similar to ratios observed in the general population. Another limitation to take into account is the use of mathematical imputation methods for prevalence calculation in the presence of missing data for 87 individuals with positive ADHD screening. However, the prevalence rate obtained by imputation was similar to the rate obtained from individuals with complete data (both rates were inside confidence interval of each other). In addition, results from CFA and regression analyses may have suffered the impact of the exclusion of 205 individuals. In order to evaluate the impact of these losses, we performed supplementary analyses showing that the only variable differing between groups with complete and incomplete data was gender, for which there was a female preponderance in the excluded group (no differences were found regarding schooling, marital status, ADHD scores, and categorical ADHD diagnosis based on screening). As gender distribution in the groups included in the analyses (n = 519) was similar to the one observed in the totality of the positively screened sample (n = 724), significant impact would not be expected in the CFA nor in the regressions results due to differential gender proportions (data available upon request).

Furthermore, since our diagnostic process was based only on self-report instead of a more reliable retrospective data, and since the 1982 Pelotas Cohort did not assess ADHD status previous to the 2012 wave and collateral information was not available, the ADHD diagnostic status could be questionable. However, our results are completely valid for clinical and research scenarios where only cross-sectional data are available. Finally, our testing for discriminant validity conveyed by ADHD symptoms might be limited since a restricted number of co-morbidities were assessed due to logistical restrictions. To mitigate this effect, we assessed the co-morbidities commonly associated with ADHD (Faraone et al. Reference Faraone, Asherson, Banaschewski, Biederman, Buitelaar, Ramos-Quiroga, Rohde, Sonuga-Barke, Tannock and Franke2015).

Clinical and research implications

The findings in this study impact the field through the many implications they have for clinicians and researchers: (a) DSM-5 criteria increases prevalence rates of ADHD during middle adulthood when comparing to rates derived from the DSM-IV; (b) in the same population, rates of DSM-5 ADHD are lower for subjects aged 30 years than for individuals aged 18-19 years; (c) as already demonstrated for the transition from adolescence to adulthood, a bi-dimensional list of symptoms as proposed by DSM-IV and DSM-5 does not reflect the latent construct of ADHD symptoms in adult population at 30 years of age; (d) as proposed by others, our findings confirm that inattentive symptoms seem to be more relevant for ADHD in adults in terms of predicting impairment and specific associations with the disorder construct; (e) findings from the CFA and regression analyses taken jointly suggest that future iterations of the classificatory system might consider exploring a smaller number of symptoms for defining the adult ADHD construct if categorical diagnosis would be retained; (f) as documented here and in other investigations, symptomatic cut-offs, trying to predict impairment, does not perform well in population studies, reinforcing that a dimensional perspective should be explored for defining ADHD; (g) adult ADHD prevalence rates would increase substantially if AoO criterion is not considered. In this context, as proposed by others (Faraone & Biederman, Reference Faraone and Biederman2016), a careful assessment of current symptoms and relevant impairments might be key for the clinical assessment of adult ADHD.

Summarizing, our results on the psychometric properties of DSM-5 ADHD criteria suggest, pending adequate replication, the need for further refinement of the criteria at least for its use in adult populations.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291716002853.

Acknowledgements

This article is based on data from the ‘Pelotas Birth Cohort, 1982’ study conducted by the Post-Graduate Program in Epidemiology at the Federal University of Pelotas, and was supported by the Welcome Trust foundation from 2004 to 2013. The International Development Research Center, World Health Organization, Overseas Development Administration, European Union, National Support Program for Centers of Excellence (PRONEX), the Brazilian National Research Council (CNPq), and the Brazilian Ministry of Health supported previous phases of the study.

Declaration of Interest

E.H.G. has been on the speakers’ bureaux on the Brazilian and International consultant board of Shire and received travel awards from Shire and Novartis to take part in scientific meetings over the last 3 years. L.A.R. has received grant or research support from, served as a consultant to, and served on the speakers’ bureaux of Eli Lilly and Co., Janssen, Novartis and Shire. The ADHD and Juvenile Bipolar Disorder Outpatient Programs chaired by Dr Rohde have received unrestricted educational and research support from the following pharmaceutical companies: Eli Lilly and Co., Janssen, Novartis, and Shire. Dr Rohde has received travel grants from Shire to take part in the 2014 APA and 2015 WFADHD congresses. He has received royalties from Artmed Editora and Oxford University Press. G.A.S. received a postdoctoral scholarship from the Brazilian Federal Agency for Support and Evaluation of Postgraduate Education (CAPES) and a Research Support Foundation from the State of Rio Grande do Sul (FAPERGS). C.K. is a Brazilian National Research Council (CNPq) level 2 researcher and receives research support from Brazilian public agencies CNPq, CAPES and FAPERGS, and authorship royalties from publishers ArtMed and Manole. All other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.