Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a serious public health problem that affects more than 240 million people worldwide (James et al., Reference James, Abate, Abate, Abay, Abbafati, Abbasi and Murray2018). Being prevalent, debilitating and recurrent, it is associated with significant personal, societal and economic costs (Greenberg, Fournier, Sisitsky, Pike, & Kessler, Reference Greenberg, Fournier, Sisitsky, Pike and Kessler2015; Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Berglund, Demler, Jin, Koretz, Merikangas and Wang2003). Unfortunately, the treatment of MDD continues to be challenging as clinicians typically rely on trial-and-error to find the most effective approach. In the STAR*D study, which provided every patient with up to four open-label treatment steps each 12 weeks in length, it was found that only ~50% of MDD patients benefited (i.e. responded by showing ⩾50% improvement in symptoms) from the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) citalopram (Trivedi et al., Reference Trivedi, Rush, Wisniewski, Nierenberg, Warden and Ritz2006), and over one-third were resistant to two or more antidepressants (Rush et al., Reference Rush, Trivedi, Wisniewski, Nierenberg, Stewart, Warden and Fava2006; Souery, Papakostas, & Trivedi, Reference Souery, Papakostas and Trivedi2006). Within primary care, the response rate to first-line antidepressants is even lower at ~30% (Katon et al., Reference Katon, Robinson, Von Korff, Lin, Bush, Ludman and Walker1996). To worsen these issues, it takes at least 4 weeks to assess whether a particular antidepressant is working. This can result in unnecessarily long trials that can heighten the risk of suicidal behavior, treatment discontinuation and patient morbidity. Identifying variables that can predict response to different antidepressants would help clinicians to decide, as early as possible, whether a particular treatment might be suitable for the patient.

Emerging research suggests that quick and non-invasive behavioral tests, which index specific neurocognitive impairments in MDD, may be predictors or moderators of antidepressant response. Executive function, psychomotor speed and/or memory tests have been found to predict outcome to treatment by fluoxetine for 4 weeks (Gudayol-Ferré et al., Reference Gudayol-Ferré, Herrera-Guzmán, Camarena, Cortés-Penagos, Herrera-Abarca, Martínez-Medina and Guàrdia-Olmos2010), 8 weeks (Dunkin et al., Reference Dunkin, Leuchter, Cook, Kasl-Godley, Abrams and Rosenberg-Thompson2000) and 12 weeks (Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Bruder, Stewart, McGrath, Halperin, Ehrlichman and Quitkin2006); escitalopram for 8 weeks (Etkin et al., Reference Etkin, Patenaude, Song, Usherwood, Rekshan, Schatzberg and Williams2015) and 12 weeks (Alexopoulos et al., Reference Alexopoulos, Manning, Kanellopoulos, McGovern, Seirup, Banerjee and Gunning2015); citalopram for 6 weeks (Kalayam & Alexopoulos, Reference Kalayam and Alexopoulos2003) and 8 weeks (Sneed et al., Reference Sneed, Roose, Keilp, Krishnan, Alexopoulos and Sackeim2007); bupropion for 8 weeks (Herrera-Guzmán et al., Reference Herrera-Guzmán, Gudayol-Ferré, Lira-Mandujano, Herrera-Abarca, Herrera-Guzmán, Montoya-Pérez and Guardia-Olmos2008) and 8–12 weeks (Bruder et al. Reference Bruder, Alvarenga, Alschuler, Abraham, Keilp, Hellerstein and McGrath2014); duloxetine for 6 weeks (Mikoteit et al., Reference Mikoteit, Hemmeter, Eckert, Brand, Bischof, Delini-Stula and Beck2015); agomelatine for 6–8 weeks (Cléry-Melin & Gorwood, Reference Cléry-Melin and Gorwood2017); as well as ketamine after 24 h (Murrough et al., Reference Murrough, Wan, Iacoviello, Collins, Solon, Glicksberg and Burdick2014, Reference Murrough, Burdick, Levitch, Perez, Brallier, Chang and Iosifescu2015) and 12 days (Shiroma, Albott, et al., Reference Shiroma, Albott, Johns, Thuras, Wels and Lim2014). However, some investigators found no evidence of an association between cognitive performance and response/remission to 8 weeks of sertraline (Etkin et al., Reference Etkin, Patenaude, Song, Usherwood, Rekshan, Schatzberg and Williams2015), venlafaxine (Etkin et al., Reference Etkin, Patenaude, Song, Usherwood, Rekshan, Schatzberg and Williams2015), and escitalopram (Alexopoulos et al., Reference Alexopoulos, Murphy, Gunning-Dixon, Kalayam, Katz, Kanellopoulos and Foxe2007), as well as 12 weeks of fluoxetine (Gudayol-Ferré et al., Reference Gudayol-Ferré, Herrera-Guzmán, Camarena, Cortés-Penagos, Herrera-Abarca, Martínez-Medina and Guàrdia-Olmos2012). Although the cause of these discrepancies is unclear, they likely stem partly from differences in specific tasks used (Groves, Douglas, & Porter, Reference Groves, Douglas and Porter2018). All these studies, however, have focused on predicting response to a single antidepressant. Depressed patients who fail to benefit from an adequate trial of SSRI are often switched to a non-SSRI agent (Fredman et al., Reference Fredman, Fava, Kienke, White, Nierenberg and Rosenbaum2000). Yet, it remains unknown whether pretreatment cognitive performance could differentiate between responders to a second antidepressant, which is administered immediately after nonresponse to a pharmacologically distinct class of medication, and non-responders resistant to both arms of treatment.

More recently, several reports have suggested that early improvements in cognitive performance may be associated with antidepressant treatment response. However, they mostly focused on ‘hot’ cognition, which is related to the processing of emotional information. Specifically, greater improvements in early emotional recognition and processing were found to predict treatment outcome with citalopram (Shiroma, Thuras, Johns, & Lim, Reference Shiroma, Thuras, Johns and Lim2014; Tranter et al., Reference Tranter, Bell, Gutting, Harmer, Healy and Anderson2009), escitalopram (Godlewska, Browning, Norbury, Cowen, & Harmer, Reference Godlewska, Browning, Norbury, Cowen and Harmer2016), and reboxetine (Tranter et al., Reference Tranter, Bell, Gutting, Harmer, Healy and Anderson2009). Surprisingly, previous studies investigating changes in ‘cold’, non-emotional cognitive variables in MDD have mostly compared performance before and after treatment (Beblo, Baumann, Bogerts, Wallesch, & Herrmann, Reference Beblo, Baumann, Bogerts, Wallesch and Herrmann1999; Hammar et al., Reference Hammar, Sørensen, Ardal, Oedegaard, Kroken, Roness and Lund2009; Herrera-Guzmán et al., Reference Herrera-Guzmán, Herrera-Abarca, Gudayol-Ferré, Herrera-Guzmán, Gómez-Carbajal, Peña-Olvira and Joan2010; Hinkelmann et al., Reference Hinkelmann, Moritz, Botzenhardt, Muhtz, Wiedemann, Kellner and Otte2012; Reppermund et al., Reference Reppermund, Zihl, Lucae, Horstmann, Kloiber, Holsboer and Ising2007; Reppermund, Ising, Lucae, & Zihl, Reference Reppermund, Ising, Lucae and Zihl2009). Only one study reported that improvements in cognitive speed, psychomotor function, motivation, and sensory perception from baseline to week 2 were predictive of treatment response to agomelatine after 6 weeks – although these were based on a self-report questionnaire rather than objective behavioral tasks (Gorwood et al., Reference Gorwood, Vaiva, Corruble, Llorca, Baylé and Courtet2015). Thus, the utility of early changes in ‘cold’ cognition as predictors of antidepressant response is still not well understood.

The current study sought to explore the two aforementioned gaps in the literature by using data from the two-staged Establishing Moderators and Biosignatures of Antidepressant Response for Clinical Care (EMBARC) trial (Trivedi et al., Reference Trivedi, McGrath, Fava, Parsey, Kurian, Phillips and Weissman2016). Task-based measures of reward processing, cognitive control, verbal fluency, psychomotor, and cognitive processing speed were collected at baseline and 1 week after the onset of an 8-week clinical trial, where outpatients with recurrent and non-psychotic MDD were randomized to receive the SSRI sertraline or placebo (stage 1). Our first goal was to examine whether changes in any behavioral tests within the first week might differentially predict eventual response to antidepressant treatment. Participants who achieved satisfactory response at the end of stage 1 continued on another 8-week course of the same medication, whereas non-responders were crossed-over under double-blinded conditions. Accordingly, sertraline non-responders received bupropion, and placebo non-responders took sertraline in stage 2. This allowed us to pursue our second goal: to identify putative pre-treatment cognitive variables that might distinguish patients who benefit from a non-serotonergic antidepressant (bupropion), after failure to respond to an SSRI (sertraline), from non-responders who are resistant to both classes of medication.

Methods

Participants

Outpatients and healthy volunteers were recruited at four sites in the United States (Columbia University, New York; Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston; University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas; and University of Michigan, Ann Arbor) after approval by the institutional review board of each site. All enrolled participants provided written informed consent and were aged between 18 and 65 years. Patients also met the criteria for MDD based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID), scored ⩾14 on the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology Self-Report (Rush et al., Reference Rush, Trivedi, Ibrahim, Carmody, Arnow, Klein and Keller2003) at both screening and randomization visits, and were free of antidepressant medication for >3 weeks prior to completing any study measures. Exclusion criteria included: history of bipolar disorder or psychosis, substance dependence (except for nicotine) in the past 6 months or substance abuse in past 2 months, active suicidality, or unstable medical conditions. In total, 634 patients were assessed for eligibility; 338 were excluded, leaving 296 individuals who were randomized in stage 1. Forty healthy controls were also enrolled. Data from participants who passed quality control criteria for at least one of the cognitive tasks at baseline and completed at least 4 weeks of treatment in stage 1 were included here.

Clinical measure of depression

17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAMD17) (Hamilton, Reference Hamilton1960)

This is a clinician-administered scale used to assess severity of symptoms of depression experienced over the past week. The HAMD17 was administered at each study visit for baseline, stage 1 (weeks 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, and 8), and stage 2 (weeks 9, 10, 12, and 16). Patients were defined as responders if they completed at least 4 weeks of treatment and showed a decrease in HAMD17 score of ⩾50% at the last observation compared to when the treatment started.

Neurocognitive measures

Probabilistic reward task (PRT)

This is a signal detection test that differentially rewarded correct responses to two difficult-to-discriminate stimuli in a 3:1 ratio, in order to assess the extent to which participants modulated their behavior as a function of reward (Pizzagalli, Jahn, & O'Shea, Reference Pizzagalli, Jahn and O'Shea2005). Performance was analyzed in terms of response bias, which is an objective measure of reward responsiveness (i.e. the tendency to choose the more rewarded stimulus). Details can be found in online Supplementary methods.

Eriksen flanker task (EFT)

On every trial, participants had to indicate, via a button press, whether an arrow in the center of the screen was pointing to the left or right. Crucially, this central arrow was presented with adjacent arrows that either pointed in the same direction (i.e. congruent condition) or opposite direction (i.e. incongruent condition) (Eriksen, Reference Eriksen1995). Inhibitory control was indexed by the interference metric (RTincongruent trials − RTcongruent trials). Details can be found in online Supplementary methods.

Choice reaction time task (CRT)

One of four possible stimuli was presented on each trial and participants had to press the button that corresponded to that stimulus as quickly as they could (Thorne, Genser, Sing, & Hegge, Reference Thorne, Genser, Sing and Hegge1985). There were 60 trials in total. Psychomotor processing speed was assessed by the median reaction time of correct trials, which is demographically-adjusted and z-scored to account for known age, gender, and education effects on scores.

A-not-B reasoning test (ABRT)

Participants were required to determine the accuracy of a statement describing the order of a pair of letters (‘AB’ and ‘BA’). The statements could be: (i) _ comes before _, (ii) _ comes after _, (iii) _ does not come before _, and (iv) _ does not come after _, in all permutations of A and B in the blanks (Baddeley, Reference Baddeley1968). There were 32 trials in total. Cognitive processing speed was assessed by the median reaction time of correct trials, which is demographically-adjusted and z-scored to account for known age, gender, and education effects on scores.

Verbal fluency test (VFT)

Participants had to produce words beginning with a specific letter within a time limit of 1 min (Benton, Hamsher, & Sivan, Reference Benton, Hamsher and Sivan1983). Three different letters (‘F’, ‘A’, and ‘S’) were used and fluency was indexed by the total number of words produced across all three letters, which is demographically-adjusted and z-scored to account for known age, gender, and education effects on scores.

Statistical analysis

Aim 1

For each task, we selected subjects who passed pre-determined quality control criteria at baseline and week 1. Separate logistic regressions were used to evaluate whether early changes from baseline in CRT, ABRT, and VFT – whose outcomes were converted to demographically-adjusted z-scores and are those used in the EMBARC study and prior studies (Gorlyn et al., Reference Gorlyn, Keilp, Grunebaum, Taylor, Oquendo, Bruder and Mann2008; Keilp, Sackeim, & Mann, Reference Keilp, Sackeim and Mann2005) – were associated with a difference in likelihood of response to sertraline v. placebo. The outcome variable was Responder (yes, no), and covariates were Treatment (sertraline, placebo), baseline score, change in score from baseline to week 1, interaction between Treatment and baseline score, interaction between Treatment and change score, and Site (Columbia, Massachusetts, Texas, Michigan). Because CRT, ABRT, and VFT analyses used demographically-adjusted z-scores, we entered age, gender, and education as additional covariates in logistic regressions for the PRT and EFT to harmonize analyses across tasks. For tasks in which early changes in performance differentially predicted response to placebo v. sertraline, additional sets of analyses were conducted. First, we broke the full logistic regression into two simpler analyses that included Treatment, either baseline score or change score as well as its interaction with Treatment, and Site. Second, analysis of covariances (ANCOVAs) were used to examine how placebo responders and non-responders compared to healthy controls. The outcome variable was change score from baseline to week 1, factor was Group (responders, non-responders, and controls) and covariates were Site and baseline score.

Aim 2

For each task, we selected subjects who passed the quality control criteria at baseline, were non-responders to sertraline or placebo in stage 1 and completed at least 4 weeks of stage 2 treatment with bupropion (after switching from sertraline) or sertraline (after switching from placebo). Separate logistic regressions were utilized to evaluate whether baseline performance in CRT, ABRT, and VFT was associated with a difference in likelihood of response to bupropion v. sertraline. The outcome variable was Responder (yes, no), and covariates were Treatment (bupropion, sertraline), baseline score, interaction between Treatment and baseline score, and Site (Columbia, Massachusetts, Texas, Michigan). To harmonize analyses across tasks, we used similar logistic regressions for PRT and EFT but with additional covariates of age, gender, and education. For tasks in which baseline performance differentially predicted response to bupropion v. sertraline, ANCOVAs were conducted to compare bupropion responders and non-responders with healthy controls. The outcome variable was pretreatment task score, factor was Group (responders, non-responders, controls) and covariates were Site, age, gender, and education. Independent samples’ t test also assessed whether responders and non-responders to bupropion and sertraline differed in baseline HAMD, week 8 HAMD, and change in HAMD from baseline to week 8.

The logistic regression analyses were not corrected for multiple comparisons as the tasks were carefully selected based on prior findings suggesting their potential for predicting response for antidepressants (Gorlyn et al., Reference Gorlyn, Keilp, Grunebaum, Taylor, Oquendo, Bruder and Mann2008; Vrieze et al., Reference Vrieze, Pizzagalli, Demyttenaere, Hompes, Sienaert, de Boer and Claes2013) and we wanted to examine the value of each test as a predictor.

Results

Early changes in psychomotor and cognitive processing speeds were associated with better response to placebo

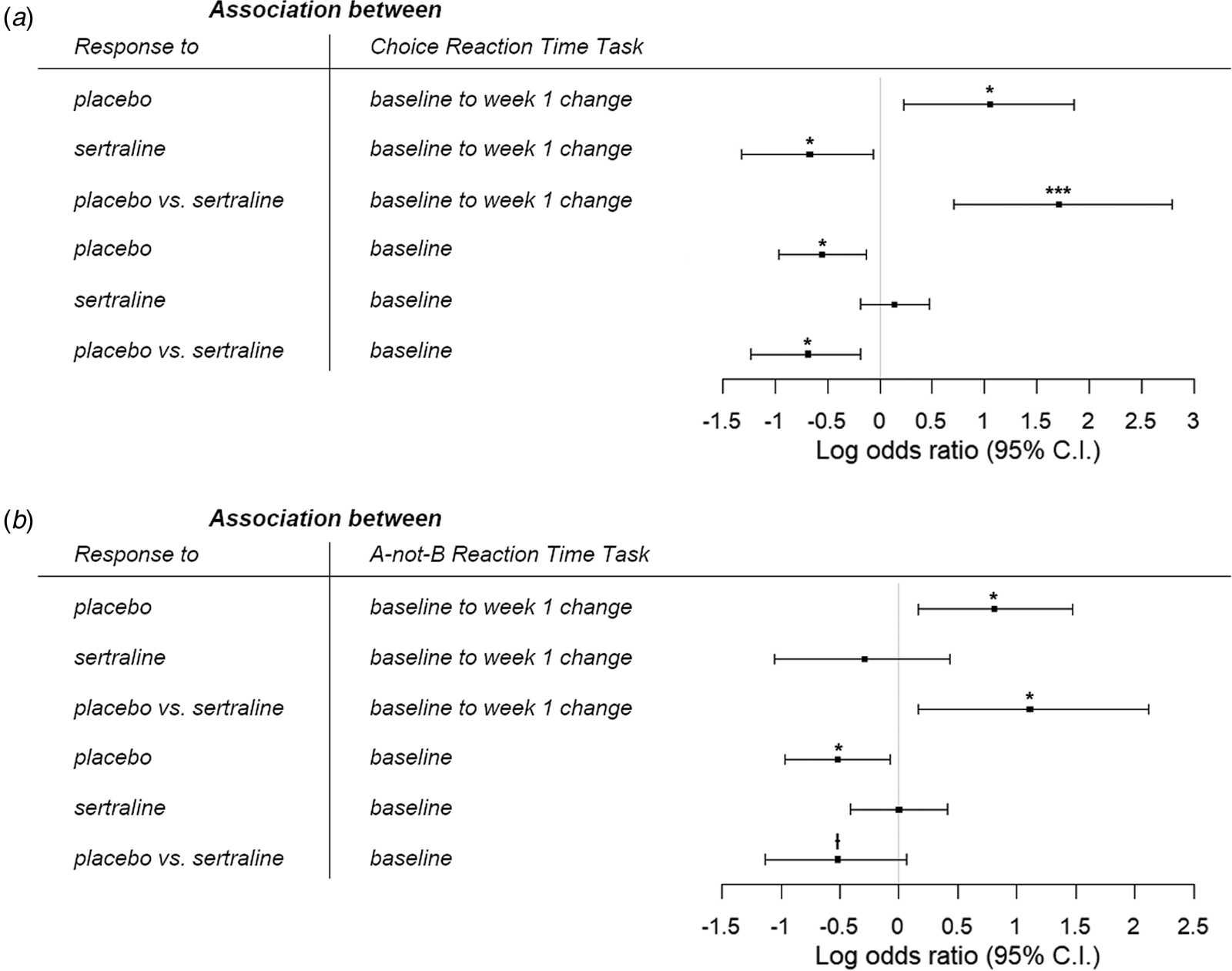

For CRT [sertraline: N = 113, age = 37.1 (13.8) years; placebo: N = 125, age = 38.0 (12.8) years], the full logistic regression revealed that greater improvement in reaction time from baseline to week 1 was associated with increased likelihood of response to placebo [B = 1.05, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.23–1.86, p = 0.012], but lower probability of sertraline response (B = −0.67, 95% CI = −1.32 to −0.06, p = 0.037). Importantly, these relationships were significantly different (B = 1.71, 95% CI = 0.71–2.79, p = 0.001), suggesting that early changes in CRT differentially predicted response to placebo and sertraline (Fig. 1a). There was also a significant difference in associations between baseline reaction time and likelihood of response to placebo v. sertraline (B = −0.69, 95% CI = −1.23 to −0.18, p = 0.010). Slower baseline reaction time was related to reduced odds of placebo response (B = −0.55, 95% CI = −0.97 to −0.13, p = 0.011), but not associated with probability of response to sertraline (B = 0.14, 95% CI = −0.18 to 0.47, p = 0.392). See online Supplementary Table S1 for details.

Fig. 1. Log odds ratio for the associations between likelihood of response to placebo and sertraline with (a) choice reaction time task and (b) A-not-B reaction time task. Greater improvements in psychomotor and cognitive processing speeds within the first week, as well as better pretreatment performance, were specifically associated with higher likelihood of response to placebo. |•ƚp < 0.10, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

In two simpler logistic regressions that separately examined the effects of baseline and change scores, we found that early changes in CRT within the first week still differentially predicted outcome to placebo and sertraline (B = 1.03, 95% CI = 0.19–1.91, p = 0.018, online Supplementary Table S2). However, there was no longer a difference in relationships between baseline CRT and response to placebo v. sertraline (B = −0.25, 95% CI = −0.69 to 0.19, p = 0.270, online Supplementary Table S3).

An ANCOVA comparing early change in CRT performance among placebo responders, non-responders, and healthy volunteers revealed a significant effect of group (F (2,157) = 4.94, p = 0.008, partial η 2 = 0.059). Post-hoc tests found that placebo responders did not differ from controls (t (84) = 0.272, p = 0.79, Cohen's d = 0.05) whereas non-responders had less improvement from baseline to week 1 than healthy individuals (t (117) = −2.38, p = 0.055, Cohen's d = 0.46) and responders (t (124) = −2.77, p = 0.019, Cohen's d = 0.51).

For ABRT [sertraline: N = 102, age = 36.8 (13.4) years; placebo: N = 114, age = 37.7 (12.7) years], we similarly found in the full logistic regression that greater improvement in reaction time from baseline to week 1 was related to higher likelihood of response to placebo (B = 0.81, 95% CI = 0.16–1.47, p = 0.015). However, change in ABRT within the first week was not associated with the odds of sertraline response (B = −0.29, 95% CI = −1.05 to 0.43, p = 0.429); and crucially, these relationships were significantly different (B = 1.11, 95% CI = 0.16–2.12, p = 0.027), suggesting that early change in ABRT differentially predicted response to placebo and sertraline. We also found a trending difference in associations between baseline reaction time and probability of response to sertraline v. placebo (B = −0.52, 95% CI = −1.13 to 0.07, p = 0.088). Slower baseline ABRT led to reduced likelihood of response to placebo (B = −0.52, 95% CI = −0.97 to −0.07, p = 0.025), but was not related to sertraline response (B = −0.002, 95% CI = −0.41 to 0.41, p = 0.994) (Fig. 1b). See online Supplementary Table S4 for details.

Simpler logistic regressions investigating the baseline and change scores separately revealed that early changes in ABRT within the first week still differentially predicted outcome to placebo and sertraline, albeit at a trend level (B = 0.74, 95% CI = 0.018–1.52, p = 0.052, online Supplementary Table S5). In contrast, the difference in relationships between baseline ABRT and response to placebo v. sertraline was no longer significant (B = −0.14, 95% CI = −0.60 to 0.32, p = 0.553, online Supplementary Table S6).

A significant effect of group was found when comparing early change in ABRT performance between placebo responders, non-responders, and healthy individuals (F (2,144) = 3.32, p = 0.039, partial η 2 = 0.044). Post-hoc tests revealed that placebo responders had greater improvement from baseline to week 1 than non-responders (t (113) = 2.49, p = 0.043, Cohen's d = 0.48), but there was no difference between controls v. responders (t (80) = 1.93, p = 0.168, Cohen's d = 0.42) and controls v. non-responders (t (106) = 0.30, p = 0.76, Cohen's d = 0.06).

In contrast, neither baseline nor early change in performance for the VFT, PRT, and EFT differentially predicted response to placebo v. sertraline. Details of all these analyses can be found in online Supplementary Tables S7–S9. At the request of an anonymous reviewer, we also repeated all the analyses by adding an additional covariate of smoking status and found that conclusions from all p value significance tests remained the same.

Pretreatment reward responsiveness, cognitive control, and verbal fluency are associated with bupropion response

We found that greater pretreatment response bias was associated with higher likelihood of response to bupropion [after switching from sertraline; N = 38, age = 38.4 (14.7) years] (B = 9.59, 95% CI = 2.46–16.3, p = 0.008). However, there was no relationship between response bias and probability of response to sertraline [after previous non-response to placebo; N = 49, age = 41.1 (13.1) years] (B = −2.20, 95% CI = −6.27 to 1.35, p = 0.249). Critically, these associations were significantly different from each other (B = 11.8, 95% CI = 4.60–20.6, p = 0.003), suggesting that baseline response bias differentially predicted response to bupropion and sertraline (Fig. 2a). An ANCOVA comparing baseline response bias among bupropion responders, non-responders, and healthy volunteers revealed a significant effect of group (F (2,67) = 6.99, p = 0.002, partial η 2 = 0.173). Post-hoc tests found no difference between responders and controls (t (53) = 0.585, p = 0.56, Cohen's d = 0.16), whereas non-responders had significantly lower response bias than healthy people (t (59) = 3.27, p = 0.005, Cohen's d = 0.86) and responders to bupropion (t (37) = 3.22, p = 0.006, Cohen's d = 1.00).

Fig. 2. Log odds ratio for the associations between likelihood of response to bupropion and sertraline with (a) probabilistic reward task, (b) verbal fluency task, and (c) Eriksen flanker task. Better response bias, greater verbal fluency, and higher response interference were specifically associated with greater likelihood of response to bupropion in patients who previously failed to respond to sertraline. |•ƚp < 0.10, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Results for the VFT [bupropion: N = 42, age = 38.0 (14.4) years; sertraline: N = 52, age = 40.6 (13.4) years] were similar to the PRT. There was a significant difference in associations between baseline verbal fluency and likelihood of response to bupropion v. sertraline (B = 1.01, 95% CI = 0.097–2.00, p = 0.035). Specifically, greater verbal fluency was related to higher probability of bupropion response at a trend level (B = 0.66, 95% CI = −0.046 to 1.37, p = 0.067), but not associated with odds of response to sertraline (B = −0.34, 95% CI = −0.97 to 0.24, p = 0.259) (Fig. 2b). There was a significant effect of group (F (2,76) = 6.20, p = 0.003, partial η 2 = 0.140) when comparing baseline performance among bupropion responders, non-responders, and healthy volunteers. Specifically, bupropion responders and controls did not differ in verbal fluency (t (56) = 0.505, p = 0.62, Cohen's d = 0.15), but non-responders performed worse than healthy individuals (t (64) = −3.45, p = 0.003, Cohen's d = 0.88) and responders (t (41) = −2.29, p = 0.074, Cohen's d = 0.71).

For the EFT [bupropion: N = 36, age = 37.4 (13.5) years; sertraline: N = 50, age = 40.4 (13.5) years], we also found a significant difference in the relationships between baseline interference and odds of response to bupropion v. sertraline (B = 0.081, 95% CI = 0.027–0.15, p = 0.007). Greater baseline interference (i.e. poorer cognitive control) was surprisingly associated with increased likelihood of bupropion response (B = 0.065, 95% CI = 0.016–0.11, p = 0.010), whereas there was no relationship between pretreatment interference and probability of response to sertraline (B = −0.016, 95% CI = −0.049 to 0.015, p = 0.321) (Fig. 2c). There was a trending effect of group (F (2,64) = 2.73, p = 0.073, partial η 2 = 0.079) when comparing pretreatment performance between bupropion responders, non-responders, and controls. Healthy individuals did not differ from responders (t (50) = −2.05, p = 0.134, Cohen's d = 0.65) or non-responders (t (58) = 0.38, p = 0.71, Cohen's d = 0.10), but responders had greater interference than non-responders at a trend level (t (35) = 2.22, p = 0.089, Cohen's d = 0.74).

Importantly, for each treatment, responders and non-responders did not differ in their HAMD17 at baseline, at week 8, and their change in HAMD17 from baseline to week 8 (see online Supplementary Tables S15 and S16). This indicates that even though the tasks were administered at baseline, they can be used to distinguish responders from non-responders in stage 2. Together, these findings suggest that reward processing, verbal fluency and cognitive control are capable of distinguishing bupropion responders who did not previously respond to sertraline from non-responders resistant to both classes of medication.

In contrast, pretreatment performance in CRT and ABRT did not differentially predict response to bupropion and sertraline. See online Supplementary Tables S10–S14 for details of these analyses. We also repeated all analyses by adding an additional covariate of smoking status and found that conclusions from all p value significance tests remained the same.

Discussion

Treatment for MDD is challenging and often proceeds via trial-and-error with limited success. To facilitate optimal treatment selection and inform timely adjustments, we sought to identify cognitive variables that can predict response in a treatment-specific manner by analyzing data from the EMBARC clinical trial. Several key findings emerged.

First, greater improvements in psychomotor and cognitive processing speeds within the first week, as well as better pretreatment performance, were specifically associated with higher likelihood of response to placebo. Moreover, the improvement of placebo responders in CRT was comparable to healthy individuals, which suggests they might possess a resilience factor. In contrast, non-responders had less CRT improvement than controls, suggesting the presence of a deficient factor. High placebo responses are commonly reported in clinical trials of novel antidepressants (Enck, Bingel, Schedlowski, & Rief, Reference Enck, Bingel, Schedlowski and Rief2013; Schatzberg, Reference Schatzberg2015) and treatment with placebo has been found to induce distinct changes in brain functioning of depressed individuals (Enck et al., Reference Enck, Bingel, Schedlowski and Rief2013; Leuchter, Cook, Witte, Morgan, & Abrams, Reference Leuchter, Cook, Witte, Morgan and Abrams2002; Mayberg et al., Reference Mayberg, Silva, Brannan, Tekell, Mahurin, McGinnis and Jerabek2002). Together, these findings suggest that, rather than having no effect, the administration of placebo is actually an active form of treatment. Accordingly, identifying MDD patients likely to respond to placebo in advance might have real-world clinical implications. Instead of a long-term antidepressant prescription, MDD patients identified as placebo responders could be treated with briefer, lower-cost interventions that are associated with fewer side effects (Enck et al., Reference Enck, Bingel, Schedlowski and Rief2013). Previous studies in this area have largely focused on demographic variables and depressive symptom severity (Entsuah & Vinall, Reference Entsuah and Vinall2007; Fournier et al., Reference Fournier, DeRubeis, Hollon, Dimidjian, Amsterdam, Shelton and Fawcett2010; Holmes, Tiwari, & Kennedy, Reference Holmes, Tiwari and Kennedy2016; Kirsch et al., Reference Kirsch, Deacon, Huedo-Medina, Scoboria, Moore and Johnson2008). More recently, Trivedi et al. analyzed 283 baseline variables from the EMBARC study and found that a higher likelihood of placebo response was predicted by baseline theta current density in the rostral anterior cingulate cortex (rACC) and several pretreatment clinical variables, such as anxious arousal, anhedonia, and neuroticism (Trivedi et al., Reference Trivedi, South, Jha, Rush, Cao, Kurian and Fava2018). However, they did not include early changes in cognition. Data from the sertraline arm were also not examined and thus, some of these predictors might not be specific to placebo. For example, Pizzagalli and coworkers demonstrated that increased baseline rACC theta activity represents a nonspecific marker of treatment outcome to both placebo and sertraline (Pizzagalli et al., Reference Pizzagalli, Webb, Dillon, Tenke, Kayser, Goer and Trivedi2018). Thus, our results extend the findings from these previous studies, suggesting the baseline and early changes in CRT and ABRT might be more specific predictors of placebo response.

Second, greater improvement in CRT within the first week was specifically associated with lower likelihood of response to sertraline. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that early changes in objective measures of ‘cold’ cognition have been reported to predict response to SSRIs. Several prior studies have focused on improvements in ‘hot’ cognition instead, consistently finding that early increases in emotional processing are associated with subsequent improvement in depressive symptoms during treatment with SSRIs (Godlewska et al., Reference Godlewska, Browning, Norbury, Cowen and Harmer2016; Shiroma, Thuras, et al., Reference Shiroma, Thuras, Johns and Lim2014; Tranter et al., Reference Tranter, Bell, Gutting, Harmer, Healy and Anderson2009). Gorwood et al. also examined early changes in ‘cold’ cognition and found that improvements in various domains such as psychomotor function, motivation, cognitive speed, and sensory perception within the first 2 weeks all predicted response to the melatonin agonist, agomelatine, after 6 weeks (Gorwood et al., Reference Gorwood, Vaiva, Corruble, Llorca, Baylé and Courtet2015). However, that study utilized a self-report questionnaire of cognition, which is inherently subjective and might be a less accurate measure of cognitive ability than behavioral tasks.

Third, better reward responsiveness, poorer cognitive control, and greater verbal fluency were associated with greater likelihood of response to bupropion in patients who previously failed to respond to sertraline. Furthermore, bupropion responders had comparable response bias and verbal fluency to healthy volunteers, whereas non-responders performed worse than controls. These findings suggest that responders to bupropion possess a resilience factor whereas a deficient factor might be present in non-responders. Prior studies have investigated cognitive predictors of treatment response to various antidepressants, including bupropion (Alexopoulos et al., Reference Alexopoulos, Murphy, Gunning-Dixon, Kalayam, Katz, Kanellopoulos and Foxe2007, Reference Alexopoulos, Manning, Kanellopoulos, McGovern, Seirup, Banerjee and Gunning2015; Bruder et al., Reference Bruder, Alvarenga, Alschuler, Abraham, Keilp, Hellerstein and McGrath2014; Cléry-Melin & Gorwood, Reference Cléry-Melin and Gorwood2017; Dunkin et al., Reference Dunkin, Leuchter, Cook, Kasl-Godley, Abrams and Rosenberg-Thompson2000; Etkin et al., Reference Etkin, Patenaude, Song, Usherwood, Rekshan, Schatzberg and Williams2015; Groves et al., Reference Groves, Douglas and Porter2018; Gudayol-Ferré et al., Reference Gudayol-Ferré, Herrera-Guzmán, Camarena, Cortés-Penagos, Herrera-Abarca, Martínez-Medina and Guàrdia-Olmos2010, Reference Gudayol-Ferré, Herrera-Guzmán, Camarena, Cortés-Penagos, Herrera-Abarca, Martínez-Medina and Guàrdia-Olmos2012; Herrera-Guzmán et al., Reference Herrera-Guzmán, Gudayol-Ferré, Lira-Mandujano, Herrera-Abarca, Herrera-Guzmán, Montoya-Pérez and Guardia-Olmos2008; Kalayam & Alexopoulos, Reference Kalayam and Alexopoulos2003; Mikoteit et al., Reference Mikoteit, Hemmeter, Eckert, Brand, Bischof, Delini-Stula and Beck2015; Murrough et al., Reference Murrough, Wan, Iacoviello, Collins, Solon, Glicksberg and Burdick2014, Reference Murrough, Burdick, Levitch, Perez, Brallier, Chang and Iosifescu2015; Shiroma, Albott, et al., Reference Shiroma, Albott, Johns, Thuras, Wels and Lim2014; Sneed et al., Reference Sneed, Roose, Keilp, Krishnan, Alexopoulos and Sackeim2007; Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Bruder, Stewart, McGrath, Halperin, Ehrlichman and Quitkin2006). For example, Herrera-Guzmán et al. (Reference Herrera-Guzmán, Gudayol-Ferré, Lira-Mandujano, Herrera-Abarca, Herrera-Guzmán, Montoya-Pérez and Guardia-Olmos2008) showed that bupropion responders had lower pretreatment cognitive processing speed (as indexed by the Stockings of Cambridge test) compared to non-responders. Another study reported that baseline cognitive control (based on the Stroop interference effect) and verbal fluency were not significantly different in eventual responders and non-responders to bupropion (Bruder et al., Reference Bruder, Alvarenga, Alschuler, Abraham, Keilp, Hellerstein and McGrath2014). In contrast, we found that lower cognitive control and higher verbal fluency predicted bupropion response, but cognitive processing speed did not. These discrepancies might have occurred due to differences in tasks used and smaller sample sizes in previous studies (N = ~20 v. N = ~40 here). Also, our findings may be specific to patients receiving secondary treatment with bupropion after failure to respond to sertraline. With regard to reward processing, our finding that bupropion responders have greater response bias on the PRT than non-responders has been reported in a recent publication (Ang et al., Reference Ang, Kaiser, Deckersbach, Almeida, Phillips, Chase and Pizzagalli2020), in which greater reward responsiveness and resting state frontostriatal functional connectivity were associated with response to bupropion, and is in line with substantial evidence showing that reward processes are modulated by dopaminergic system in the brain (Berridge, Robinson, & Aldridge, Reference Berridge, Robinson and Aldridge2009). It is also consistent with a recent study showing depressed individuals with enhanced baseline response bias respond more favorably to pramipexole, a selective dopamine agonist (Whitton et al., Reference Whitton, Reinen, Slifstein, Ang, McGrath, Iosifescu and Schneier2020). In sum, our study is the first to address cognitive predictors of response to the noradrenaline/dopamine reuptake inhibitor (NDRI) bupropion following a failure to respond to the SSRI sertraline. This might have significant clinical value in identifying patients who are likely to respond to secondary treatment with bupropion and those who are unlikely to benefit from both SSRIs and NDRIs, so that they can be recommended alternative forms of treatment.

Limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, multiple logistic regressions were conducted, but none of the findings would survive multiple comparisons. Although this might increase the chances of committing a type 1 error, our study is exploratory in nature and we were specifically interested in identifying whether each of the cognitive tasks could be a potential predictor of treatment outcome (Huberty & Morris, Reference Huberty and Morris1989). This liberal approach may not be stringent enough and thus, our findings are tentative and require replication. Second, this study adopted relatively strict inclusion criteria in order to minimize clinical heterogeneity. Thus, it is unclear whether findings will generalize to other depressed samples, such as those with psychosis or substance dependence. Third, this study did not exclude participants who had tobacco use disorder. Although chronic cigarette smoking has been associated with poorer cognitive performance across multiple domains (Durazzo, Meyerhoff, & Nixon, Reference Durazzo, Meyerhoff and Nixon2012; Nooyens, van Gelder, & Verschuren, Reference Nooyens, van Gelder and Verschuren2008), all conclusions remained after accounting for an additional covariate of smoking status in our analyses.

Conclusion

Cognitive tasks that are quick, non-invasive, and easy to administer may have important clinical value as predictors of response to antidepressant treatment. The current study showed that psychomotor and cognitive processing speed after 1 week were associated with enhanced clinical response to placebo. Reward sensitivity, cognitive control, and verbal fluency at baseline also differentiated bupropion responders, who did not respond to sertraline previously, from non-responders resistant to both classes of medication. These initial results warrant further scrutiny for possible implementation in clinical care.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720004286.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Daniel G. Dillon, Ph.D., for his support in the EMBARC study, as well as Boyu Ren, Ph.D., for providing advice on our statistical analyses.

Financial support

The EMBARC study was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health under award numbers U01MH092221 (M.H. Trivedi) and U01MH092250 (P.J. McGrath, R.V. Parsey, and M.M. Weissman). Y.S.A. was supported by a Kaplen Fellowship in Depression from Harvard Medical School, as well as the National Science Scholarship from the Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR) in Singapore. D.A.P. was partially supported by R37 MH068376. This study was supported by the EMBARC National Coordinating Center at UT Southwestern Medical Center, Madhukar H. Trivedi, M.D., Coordinating PI, and the Data Center at Columbia and Stony Brook Universities. The funder has no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of interest

In the last 3 years, the authors report the following financial disclosures, for activities unrelated to the current research: Dr Carmody: owns stock in Vertex Pharmaceuticals and CRISPR Therapeutics. Dr Fava: Dr Fava reports the following lifetime disclosures: http://mghcme.org/faculty/faculty-detail/maurizio_fava. Dr Weissman: funding from NIMH, the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression (NARSAD), the Sackler Foundation, and the Templeton Foundation; royalties from the Oxford University Press, Perseus Press, the American Psychiatric Association Press, and MultiHealth Systems. Dr Oquendo: funding from NIMH; royalties for the commercial use of the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale; equity in Mantra, Inc. Her family owns stock in Bristol Myers Squibb. Dr McInnis: funding from NIMH; consulting fees from Janssen and Otsuka Pharmaceuticals. Dr Trivedi: reports the following lifetime disclosures: research support from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Cyberonics Inc., National Alliance for Research in Schizophrenia and Depression, National Institute of Mental Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Johnson & Johnson, and consulting and speaker fees from Abbott Laboratories Inc., Akzo (Organon Pharmaceuticals Inc.), Allergan Sales LLC, Alkermes, AstraZeneca, Axon Advisors, Brintellix, Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, Cephalon Inc., Cerecor, Eli Lilly & Company, Evotec, Fabre Kramer Pharmaceuticals Inc., Forest Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, Health Research Associates, Johnson & Johnson, Lundbeck, MedAvante Medscape, Medtronic, Merck, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Development America Inc., MSI Methylation Sciences Inc., Nestle Health Science-PamLab Inc., Naurex, Neuronetics, One Carbon Therapeutics Ltd., Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, Pamlab, Parke-Davis Pharmaceuticals Inc., Pfizer Inc., PgxHealth, Phoenix Marketing Solutions, Rexahn Pharmaceuticals, Ridge Diagnostics, Roche Products Ltd., Sepracor, SHIRE Development, Sierra, SK Life and Science, Sunovion, Takeda, Tal Medical/Puretech Venture, Targacept, Transcept, VantagePoint, Vivus, and Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories. Dr Pizzagalli: funding from NIMH, Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, the Dana Foundation, and Millennium Pharmaceuticals; consulting fees from BlackThorn Therapeutics, Boehreinger Ingelheim, Compass Pathway, Engrail Pharmaceuticals, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals; one honorarium from Alkermes; stock options from BlackThorn Therapeutics. Dr Pizzagalli has a financial interest in BlackThorn Therapeutics, which has licensed the copyright to the Probabilistic Reward Task through Harvard University. Dr Pizzagalli's interests were reviewed and are managed by McLean Hospital and Partners HealthCare in accordance with their conflict of interest policies. All other authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.