Introduction

Emotional (or internalizing) disorders form the largest group of mental disorders, consisting of states with increased levels of anxiety, depression, fear and somatic symptoms. They include generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), unipolar depression, panic disorder, phobic disorders, obsessional states, dysthymic disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and somatoform disorders. We have also included neurasthaenia, as this diagnosis is commonly made in many parts of the world, and is in the ICD-10. We have preferred the term ‘emotional’ because we include somatoform disorders in the group. Depressive, anxious and somatoform symptoms occur together in general medical settings, and share many common features. Within this class there are differences in the genetic factors, the early environments and the biological measures, but there are also important similarities that justify bringing the disorders into a single group.

The current classifications are based upon similarities between the clinical manifestations of these disorders. The purpose of the proposed meta-structure, of which this paper is a part, is to determine whether it is feasible to identify disorder groupings based on aetiology (Andrews et al. Reference Andrews, Goldberg, Krueger, Carpenter, Hyman, Sachdev and Pine2009a, b; Carpenter et al. Reference Carpenter, Bustillo, Thaker, van Os, Krueger and Green2009; Krueger & South, Reference Krueger and South2009; Sachdev et al. Reference Sachdev, Andrews, Hobbs, Sunderland and Anderson2009). The focus of this paper is whether the existing anxiety, mood and somatoform disorders could be grouped as aetiologically similar disorders. ‘Similar’ is used here in the sense that the pattern of risk factors implicated in the development of emotional disorders is consistent across the disorders rather than suggesting that these disorders have a single, common cause.

Method

A Study Group of the DSM-V Task Force of the American Psychiatric Association (APA) has recently recommended 11 ‘validating criteria’ that could be used to identify groups of aetiologically related disorders without altering the current diagnostic criteria (Hyman et al., personal communication, 3 December 2007). These are:

(1) genetic factors;

(2) familiality;

(3) early environmental adversity;

(4) temperamental antecedents;

(5) neural substrates;

(6) biomarkers;

(7) cognitive and emotional processing;

(8) differences and similarities in symptomatology;

(9) co-morbidity;

(10) course;

(11) treatment.

Scopus, EMBASE, PsychINFO and Medline searches were conducted to identify English-language literature that considered the risk associated with each validating criterion and the emotional disorders. Large epidemiological data samples using the current classificatory criteria were preferred over small clinical samples. The literature that would support or negate the present thesis is selectively reviewed. If the Committees responsible for the revision of DSM-IV and ICD-10 agree that an aetiologically driven classification is feasible, the final cluster-membership of disorders can be determined by systematic reviews.

Results

Genetic factors

Genetic-epidemiological twin data have been used to identify two broad genetic risks of the common mental disorders: internalizing (emotional) and externalizing liabilities (e.g. Kendler et al. Reference Kendler, Prescott, Myers and Neale2003). The Kendler group report that the internalizing genetic risk factor is composed of discrete but intercorrelated factors: one for anxious-misery with major depressive disorder (MDD) and GAD, and the other a fear risk factor with phobic disorders. Panic loaded moderately on the first genetic risk factor, however, was the only investigated internalizing syndrome to have a significant disorder-specific genetic risk (Kendler et al. Reference Kendler, Prescott, Myers and Neale2003). This internalizing tripartite model is somewhat similar to that advocated initially by Clark & Watson (Reference Clark and Watson1991). Kendler et al. (Reference Kendler, Prescott, Myers and Neale2003) did not include PTSD, neurasthaenia, obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD), somatoform disorders or dysthymia. Nevertheless, co-morbidity studies that have implemented similar statistical analyses to those used by Kendler and colleagues have reported that PTSD (Cox et al. Reference Cox, Clara and Enns2002; Slade & Watson, Reference Slade and Watson2006), neurasthaenia and dysthymia (Slade & Watson, Reference Slade and Watson2006) load on the anxious-misery/distress factor and OCD is more related to the fear risk factor (Slade & Watson, Reference Slade and Watson2006). Twin data have also been used to show that the genetic risk associated with MDD is shared substantially with GAD (Kendler et al. Reference Kendler, Neale, Kessler, Heath and Eaves1992), and both are strongly associated with neuroticism (Hettema et al. Reference Hettema, Prescott and Kendler2004; Kendler et al. Reference Kendler, Gatz, Gardner and Pedersen2006). Neuroticism also explains some, but not all, of the common genetic risk of several of the internalizing/emotional disorders (e.g. Hettema et al. Reference Hettema, Neale, Myers, Prescott and Kendler2006: MDD, GAD, Panic, Agoraphobia, Social Phobia, Animal and Situational Phobias; Kendler et al. Reference Kendler, Gardner, Gatz and Pedersen2007: GAD and MDD).

Studies of the genetic factors of the emotional disorders have often compared probands with a particular disorder with normal controls, or have tended to stay within a particular chapter of the major classifications; so that unipolar depression has been compared with other mood disorders, and various anxiety disorders have been compared with one another. However, there have been notable exceptions to this, and these are shown as Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of studies that have linked genetic factors across the main symptom domains

DD, Dysthymic disorder; GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; MDD, major depressive disorder; N, neuroticism; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

Genomic screens have not yet identified specific genes for the majority of the emotional disorders, notwithstanding recognition of the broad genetic liabilities to mental illness. The only gene identified for an emotional disorder is the 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) transporter gene, first shown to have an important gene–environment interaction in the aetiology of depression by Caspi et al. (Reference Caspi, Sugden, Moffitt, Taylor, Craig, Harrington, McClay, Mill, Martin, Braithwaite and Poulton2003), and since confirmed by several different studies (e.g. Eley et al. Reference Eley, Sugden, Corsico, Gregory, Sham, McGuffin, Plomin and Craig2004; Kendler et al. Reference Kendler, Kuhn, Vittum, Prescott and Riley2005; Wilhelm et al. Reference Wilhelm, Mitchell and Niven2006). This gene has also been implicated in anxious traits including neuroticism and harm avoidance by Lesch et al. (Reference Lesch, Bengel, Heils, Sabol, Greenberg, Petri, Benjamin, Muller, Hamer and Murphy1996), who found that individuals with one or two short forms of the allele had higher rates of neuroticism and its anxious, depressive and angry hostility subfacets. Nevertheless, the role of the 5-HT gene remains inconclusive, as other studies have failed to replicate it (Gillespie et al. Reference Gillespie, Whitfield, Williams, Heath and Martin2005; Willis-Owen et al. Reference Willis-Owen, Turri, Munafo, Surtees, Wainwright, Brixey and Flint2005).

We seem to have two overlapping groups of genes dealing with anxious-misery and fear, but there are also other genes not shared with neuroticism. For example, Kendler et al. (Reference Kendler, Gatz, Gardner and Pedersen2006) show that although the association between neuroticism and MDD results from shared genetic risk factors, a substantial proportion of the genetic vulnerability to MDD is not reflected in neuroticism. There is indirect evidence for common genes for PTSD, somatoform disorders, neurasthaenia, obsessional disorder and dysthymia but the degree of overlap remains to be clarified.

Familiality

The present contention is not that there are no differences between probands with different emotional disorders, it is that there is important common ground between them. This is confirmed by the higher rates of other emotional disorders in the first-degree relatives (FDRs) of affected probands than is expected in the FDRs of normal controls (see Table 2). Eley et al. (Reference Eley, Collier, McGuffin, McGuffin, Owen and Gottesman2002) show that although the rate for GAD (with or without other disorders such as panic or MDD) varies from 9% to 20% in FDRs of GAD probands, the risk for HC ranges from 2% to 4%. There is considerable variation in rates of GAD in FDRs of patients with fear disorders, although they are always raised relative to normal controls. There is also some support for the specific transmission of individual emotional disorders. For example, Mendlewicz et al. (Reference Mendlewicz, Papadimitrou and Wilmotte1993) showed that the morbid risk of panic disorder is significantly higher in panic-affected probands than FDRs of probands with GAD, MDD and HC. It is also noteworthy that, though not reaching significance the risk of GAD, MDD and panic disorder in FDRs of affected probands were greater than in FDRs of HC. Consistent with Mendlewicz et al. and the later findings of Kendler et al. (Reference Kendler, Prescott, Myers and Neale2003), as noted above, Goldstein et al. (Reference Goldstein, Weissman, Adams, Horwath, Lish, Charney, Woods, Sobin and Wickramaratne1994) report that panic disorder has a specific genetic component with a possible increased risk of social phobia. Fyer et al. (Reference Fyer, Mannuzza, Chapman, Martin and Klein1995) also argue that ‘pure’ panic and fear disorders have some disorder-specific genetic risk. In terms of OCD, Hanna et al. (Reference Hanna, Fisher, Chadha, Himle and van Etten2005) report that there are higher rates of anxiety disorders in FDRs of probands with familial OCD in comparison to sporadic forms of OCD.

Table 2. Summary of studies that have linked familial factors across the main symptom domains

AG, Agoraphobia; DD, dysthymic disorder; FDR, first-degree relative; GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; HC, healthy controls; MDD, major depressive disorder; OCD, obsessive–compulsive disorder; Phob, phobic disorders; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

Complementary to the findings of studies where offspring are the affected proband, investigations of depressed parents and grandparents have also found increased risk of anxiety (Lieb et al. Reference Lieb, Isensee, Hofler, Pfister and Wittchen2002a; Weissman et al. Reference Weissman, Wickramaratne, Nomura, Warner, Verdeli, Pilowsky, Grillon and Bruder2005), depression and substance disorders in offspring (e.g. Lieb et al. Reference Lieb, Isensee, Hofler, Pfister and Wittchen2002a). The inter-cluster familiality of some of the emotional disorders and some of the externalizing disorders may be explained by common genetically determined vulnerability or by social learning within families. Family studies are a weaker test of the hypothesis being put forward than genetic-epidemiological twin data because familial aggregation of different emotional disorders reflect not only common genetics but also social learning within families. The various studies of familiality reported in Table 2 do not report rates for neurasthaenia or somatoform disorders, so it cannot be claimed that there is at present complete evidence for the proposed cluster from familiality data. To the extent that familiality data support the present hypothesis, it is in the higher rates of anxiety disorders in FDRs of the diagnoses included in the cluster.

Early environmental adversity

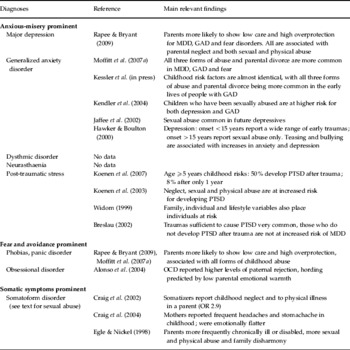

Most adult psychiatric disorders including the ‘stress-related and fear circuitry’ disorders, and a range of other syndromes such as behaviour disorders and substance use disorders, have their roots in early life (Kim-Cohen et al. Reference Kim-Cohen, Caspi, Moffitt, Harrington, Milne and Poulton2003). However, evidence for specificity between adult diagnoses is less impressive than the similarities (see Table 3).

Table 3. Summary of studies that have disadvantages in shared early life across the main symptom domains

GAD, Generalized anxiety disorder; MDD, major depressive disorder; OCD, obsessive–compulsive disorder; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; OR, odds ratio.

For most members of this cluster, early environmental factors that predispose to the disorder have much in common, but co-morbidity may account for some of the reported findings; so that the factors may be related only to anxious and depressive syndromes. However, for obsessional and somatoform disorders, other specific factors may be operating. Findings of early adversity in obsessional disorder have been inconsistent and apparent support for early adversity may be due to accompanying anxious symptoms such as cognitive/perceptual biases (Alonso et al. Reference Alonso, Menchon, Mataix-Cols, Pifarre, Urretavizcaya, Crespo, Jimenez, Vallejo and Vallejo2004). In somatoform disorders, several studies report higher rates of childhood illness in addition to measures of childhood adversity. Sexual abuse in childhood has been found to be associated with a wide range of functional symptoms, such as somatization disorders (Walker et al. Reference Walker, Gelfand, Gelfand, Koss and Katon1995), somatoform symptoms (Hexel & Sonneck, Reference Hexel and Sonneck2002), irritable bowel disorder (Reilly et al. Reference Reilly, Baker, Rhodes and Salmon1999), conversion disorder (Roelofs et al. Reference Roelofs, Keijsers, Hoogduin, Naring and Moene2002) and functional pelvic pain (Reiter et al. Reference Reiter, Shakerin, Gambone and Milburn1991).

Heim and colleagues (Heim et al. Reference Heim, Newport, Heit, Graham, Wilcox, Bonsall, Miller and Nemeroff2000, Heim & Nemeroff, Reference Heim and Nemeroff2001) argue that children exposed to traumatic life experiences develop an increased sensitization of those parts of the nervous system related to stress and emotion, and in consequence develop an increased vulnerability to later stress due to hyper-reactivity of corticotrophin-releasing factor, as well as to other neurotransmitter systems. In summary, early adversity seems to increase the probability of most later disorders, but there is little reason to suggest effects on specific disorders.

Temperament antecedents

Negative affect (neuroticism) makes a strong contribution to all the emotional disorders. All those who have reported multivariate analyses of self-report instruments of these disorders find a large general distress factor running across items, and this has been variously named ‘neuroticism’ (Eysenck, Reference Eysenck1964; and many other authors), ‘negative emotionality’ (Harkness et al. Reference Harkness, McNulty and Ben-Porath1995) and ‘negative affectivity’ (Watson et al. Reference Watson, Clark and Tellegen1984). Jardine et al. (Reference Jardine, Martin and Henderson1984) studied the co-variation between neuroticism and current depressive and anxious symptoms and reported that, in both sexes, there is a genetic correlation between symptom scores and neuroticism of approximately 0.8. Khan et al. (Reference Khan, Jacobson, Gardner, Prescott and Kendler2005) studied emotional disorders using the Virginia Twin Register, and concluded that ‘neuroticism not only contributed to individual diagnoses but also accounted for a significant part of the life-time comorbidity of common psychiatric disorders. The most striking finding was that neuroticism, on average, accounted for 26% of the co-morbidity among the[se] disorders.’ Hettema et al. (Reference Hettema, Neale, Myers, Prescott and Kendler2006) concluded that more than half of the genetic correlations between the internalizing disorders can be explained by the genetic risk of neuroticism (see Table 4). In the case of emotional disorders and, to a much lesser extent, externalizing disorders, high scores for negative emotionality precede the development of these disorders (Kendler et al. Reference Kendler, Neale, Kessler, Heath and Eaves1993; Krueger, Reference Krueger1999b). We are not aware of data showing the same for the other proposed clusters.

Table 4. Summary of studies that have linked temperament across the main symptom domains

DD, Dysthymic disorder; FDR, first-degree relative; GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; MDD, major depressive disorder; N, Neuroticism; OCD, obsessive–compulsive disorder; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

In summary, there is strong support for high neuroticism scores in all the proposed disorders in the cluster. However, on its own this is not a sufficient cause of emotional disorders because neuroticism scores are raised relative to healthy controls in other mental disorders; for example, neuroticism also contributes to the externalizing disorders to a smaller extent (10–12%) and novelty seeking (7–14%) also contributes to the co-morbidity between these disorders (Khan et al. Reference Khan, Jacobson, Gardner, Prescott and Kendler2005).

Neural substrates

Neuroimaging studies

The problem with making definitive statements about this topic is that, although there is a great deal of information about the neural substrate of both depression and the fear disorders, there have been remarkably few imaging studies that have examined functional and structural central nervous system disruptions in GAD (Martin & Nemeroff, Reference Martin, Nemeroff, Goldberg, Kendler, Sirovatka and Regierin press). Nonetheless, and despite differences between anxious and depressed subjects, there are substantial similarities between the majority of the emotional disorders.

The medial prefrontal cortex has a general role in emotional processing, being activated in multiple individual emotions (activated in four of five specific emotions in at least 40% of studies meta-analysed by Phan et al. Reference Phan, Wager, Taylor and Liberzon2002). The medial prefrontal cortex seems to be involved in any situation where there is a relative focus on internal state or self-reference rather than attention to the outside world; thus, inappropriate attention is paid to internal stimuli at the expense of the external world. The insula is a region of limbic sensory cortex responsible for the generation of one's mental image of one's physical state (Rauch & Drevets, Reference Rauch, Drevets, Andrews, Charney, Sirovatka and Regier2009). The anterior insular cortex of the non-dominant (right) hemisphere is thought to more specifically subserve evaluation of self-awareness, the ‘feeling self’. It is reciprocally connected to the right orbitofrontal cortex, a region further implicated in reward evaluation and decision making (Craig, Reference Craig2002). This may account for the close association between the somatoform disorders and the anxious-misery disorders. There is considerable overlap between the clinical syndromes and the neural circuits involved, and it is clear that different circuits are involved across different diagnostic subgroups.

The emotional disorders as currently defined share certain common features, namely activation of visceral brain centres (amygdala, hypothalamus, locus coeruleus, dorsal raphe), and involve interpretation of novel stimuli that may have survival consequences (loss, threat, fear). The amygdala organizes the emotional response to stress; it is thought to be overactive in MDD and fear-disorder patients and may underlie the rumination on aversive or guilt-provoking memories that is common to both the mood and anxiety disorders (for mood disorders: Drevets, Reference Drevets2001, Reference Drevets2003; for anxiety disorders: Charney, Reference Charney2003; Rauch et al. Reference Rauch, Shin and Wright2003; Etkin & Wagner, Reference Etkin and Wager2007). In addition to exaggerated amygdala responses, Rauch et al. (Reference Rauch, Shin and Phelps2006) argue that PTSD is characterized by deficient frontal cortical and hippocampal functioning. Etkin & Wager (Reference Etkin and Wager2007) reported that PTSD, social anxiety disorder and specific phobia all showed greater activity than matched comparison subjects in the amygdala and insula, but PTSD showed hypo-activation in the dorsal and rostral anterior cingulate cortices and the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, structures linked to the experience and regulation of emotion. Rapoport & Shaw (Reference Rapoport, Shaw, Rutter, Bishop, Pine, Scott, Stevenson, Taylor and Thapar2008) implicate the ‘cortico-striato-thalamocortical loop’ in OCD; limbic structures may account for the strong anxiety component. The role of the amygdala in GAD patients is not well established. Nonetheless, a recent functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) study of youth with GAD found that right amygdala activation associated with emotional stimuli was positively correlated with anxiety severity. The right amygdala and the right ventrolateral prefrontal cortex also had strong negative coupling in reaction to the emotional stimuli (Monk et al. Reference Monk, Telzer, Mogg, Bradley, Mai, Louro, Chen, McClure-Tone, Ernst and Pine2008). Although more investigation is required into the neural substrates of GAD, this finding and its similarities to other mood and anxiety neuroimaging studies support the notion of a similar ‘emotional’ neural substrate.

Neurotransmitters

Abnormalities of the 5-HT transporter gene are associated with trait neuroticism as measured by the Neuroticism–Extroversion–Openness (NEO) Personality Inventory (Schinka et al. Reference Schinka, Busch and Robichaux-Keene2004; Sen et al. Reference Sen, Burmeister and Ghosh2004). Individuals with this abnormality may also be at risk for unipolar depression (Lotich & Pollock, Reference Lotich and Pollock2004; also see above in ‘Genetic factors’ section), and have increased amygdala activity in response to fearful stimuli, when compared to those with a normal homozygous long gene (Hariri et al. Reference Hariri, Mattay, Tessitore, Kolachana, Fera, Goldman, Egan and Weinberger2002). There are abnormalities of the norepinephrine and serotonin systems in most of the emotional disorders, although there are also specific differences between anxiety and depression (Charney, Reference Charney2003; Martin & Nemeroff, Reference Martin, Nemeroff, Goldberg, Kendler, Sirovatka and Regierin press).

Biomarkers

We are not aware of a biomarker that features in all the emotional disorders. Individuals reporting elevated levels of negative affect consistently show augmented base startle reactivity (Cook et al. Reference Cook, Hawk, Davis and Stevenson1991; Lang et al. Reference Lang, Bradley, Cuthbert, Patrick, Chapman, Chapman and Fowles1993). Tomarken & Keener (Reference Tomarken and Keener1998) report that depressed patients are characterized by increased activity in the right frontal cortex; however, not all depressed patients show this, so it cannot be thought of as a universal biomarker. Biomarkers for depression include abnormalities of the P300 response (e.g. Kemp et al. Reference Kemp, Hopkinson, Hermens, Rowe, Sumich, Clark, Drinkenburg, Abdi, Penrose, McFarlane, Boyce, Gordon and Williams2009). The problem is that these studies do not include patients with the range of disorders that would be necessary to give a firm view about this validator.

Cognitive and emotional processing

It is not the present contention that there are no differences between the various diagnoses contained in the emotional disorders cluster, and there are indeed major differences between them in terms of cognitive and emotional processes. Nonetheless, there are some common themes. Beck (Reference Beck1976) related anxiety to helplessness and depression to hopelessness. Those who become uncertain about their ability to control outcomes (entrapment, in terms of their life situation) and who are relatively certain about negative outcomes (i.e. hopeless) may be expected to be both depressed and anxious. Thus, those who are both helpless and hopeless may be expected to be ‘co-morbid’.

Anxious and depressed subjects differ in several important respects, but share biased judgements on the likelihood that negative events will occur (Krantz & Hammen, Reference Krantz and Hammen1979; Butler & Mathews, Reference Butler and Mathews1983). MacLeod & Byrne (Reference MacLeod and Byrne1996) reported that those who are both depressed and anxious showed both greater anticipation of negative experiences and reduced anticipation of positive experiences, whereas those who are only anxious showed only the former.

Gilboa-Schechtman et al. (Reference Gilboa-Schechtman, Erhard-Weiss and Jeczemien2002) found that the well-documented memory biases for linguistic material in depressed subjects also apply to visual material. They reported that co-morbid anxious depressives, relative to normal controls, exhibited an enhanced memory for sad and angry versus happy expressions, whereas those who were only anxious did not display this bias.

Mineka et al. (Reference Mineka, Watson and Clark1998) conclude that most evidence suggests that anxiety is associated with automatic attentional biases for emotion-relevant (threatening) material, that depression is associated with memory biases for emotion-relevant (negative) information, and that both anxiety and depression are associated with judgemental or interpretive biases. They conclude that the view that anxious and depressive disorders are two different disorders is replaced by ‘a more nuanced view in which anxiety and depression are posited to have both shared, common components and specific, unique components’.

Differences and similarities in symptomatology

As both the DSM and ICD systems require very different sets of symptoms to achieve diagnostic status within the class of emotional disorders, it is paradoxical that psychiatric screening questionnaires (e.g. the 12-item General Health Questionnaire) are effective in detecting a wide range of emotional disorders. The reason for this is that all the emotional disorders share a common core of symptoms that are of fairly low severity (Grayson et al. Reference Grayson, Bridges, Duncan-Jones and Goldberg1987; Goldberg et al. Reference Goldberg, Gater, Sartorius, Ustun, Piccinelli, Gureje and Rutter1997). Examples of these milder symptoms are sleeping badly, lacking energy, feeling tired, feeling irritable, worrying and feeling gloomy. It is possible for individuals with an externalizing disorder such as drug dependence, a neurocognitive disorder such as mild dementia or a psychosis such as early schizophrenia to have these symptoms as well; but most of them do not. However, by the time a person is diagnosable with an emotional disorder, they will possess these non-specific symptoms.

Latent structure of symptoms

The underlying relationships between individual symptoms can also be established by latent trait analysis and latent class analysis (Goldberg et al. Reference Goldberg, Bridges, Duncan-Jones and Grayson1987). When latent trait analysis is applied to data from research interviews such as the Present State Examination, both from community samples and primary care attenders, this produces three correlated traits: anxious symptoms, depressive symptoms and fear symptoms (Ormel et al. Reference Ormel, Oldehinkel, Goldberg, Hodiamont, Wilimink and Bridges1995). This high correlation is of course due to the large general factor in an unrotated factor analysis of such symptoms.

Factor analysis

Jacob (Reference Jacob, Goldberg, Kendler, Sirovatka and Regierin press) analysed data from confirmatory factor analysis of psychiatric research interviews given to subjects in seven different countries, and reported that a single factor solution provided only a marginally less good solution than one with two, highly correlated factors of anxiety and depression. Krueger et al. (Reference Krueger, Caspi, Moffitt and Silva1998) compared mental disorders at aged 18 and 21 of a prospectively assessed birth cohort, and argued that an internalizing/externalizing model provided a more optimal representation of an individual's course than more complex models. They argued that co-morbidity may result from common mental disorders being reliable, covariant indicators of stable, underlying processes, such as ‘internalization’. Krueger et al. (Reference Krueger, Chentsova-Dutton, Markon, Goldberg and Ormel2003) reported similar findings using exploratory factor analysis using the CIDI (Primary Care Version) followed by confirmatory factor analysis on a large data set collected in general health-care settings in 14 different countries. Here, a two-factor model with depression, anxious symptoms (worry and arousal), neurasthaenia, somatization and hypochondriasis on the first, and alcohol use disorders on the second provided the best fit for the data. With the US and German data, a three-factor model with depression and anxiety symptoms on an ‘anxious misery’ factor, neurasthaenia, somatization and hypochondriasis loading on a ‘somatization factor’, and alcohol use disorders on a third also provided a reasonably good fit, although correlations between the various factors were substantial, at around +0.70.

Co-morbidity

High rates of co-morbidity are encountered in both primary care (Ustun & Sartorius, Reference Ustun and Sartorius1995) and community settings (Kessler et al. Reference Kessler, Nelson, McGonagle, Lui, Swartz and Blazer1996, Reference Kessler, Wai, Chui, Delmer, Merikangas and Walters2005, Reference Kessler, Gruber, Hettema, Hwang, Sampson, Yonkers, Goldberg, Kendler, Sirovatka and Regierin press). This is because emotional disorders reflect common dimensions of symptoms, and the various symptoms that characterize each emotional disorder represent different combinations of phobic, anxious, depressive or somatic components (Krueger et al. Reference Krueger, Chentsova-Dutton, Markon, Goldberg and Ormel2003). As severity of disorder increases, so does the likelihood of an individual satisfying more than one of these disorders. If ‘co-morbid’ cases are merely more severe examples of an underlying distress syndrome, it remains to ask how they differ from cases of uncomplicated disorder, such as depressive episode or GAD. In the Dunedin study, co-morbid cases had lower self-esteem and higher neuroticism in adolescence than either disorder on its own (Moffitt et al. Reference Moffitt, Caspi, Harrington, Milne, Melchior, Goldberg and Poulton2007a). In a prospective study of children with OCD, Swedo et al. (Reference Swedo, Rapoport, Leonard, Leane and Cheslow1989) found these disorders co-morbid with MDD in 35%, overanxious in 18%, phobias in 17% and only occurring on its own in 26% of cases.

Factor analysis of the relationship between diagnoses in this cluster shows that a three-factor model produces the best fit, with the three factors being anxious-misery disorders, fear disorders and externalizing disorders. Somatic symptoms were not assessed in this study (Krueger, Reference Krueger1999a, see Fig. 1). These relationships have now been confirmed by community surveys in The Netherlands (Vollebergh et al. Reference Vollebergh, Iedema, Bijl, de Graaf, Smit and Ormel2001) and Australia (Slade & Watson, Reference Slade and Watson2006). A very similar pattern is reported in two other studies (Cox et al. Reference Cox, Clara and Enns2002; Kendler et al. Reference Kendler, Prescott, Myers and Neale2003). Other data sets have also identified the internalizing/emotional and externalizing disorders factors (Krueger et al. Reference Krueger, Caspi, Moffitt and Silva1998, Reference Krueger, McGrue and Iacono2001, Reference Krueger, Chentsova-Dutton, Markon, Goldberg and Ormel2003; Kessler et al. Reference Kessler, Wai, Chui, Delmer, Merikangas and Walters2005; Lahey et al. Reference Lahey, Rathouz, van Hulle, Urbano, Krueger, Applegate, Garriock, Chapman and Waldman2008). They have led to a call for a revised arrangement of diagnostic constructs in DSM-V (Clark & Watson, Reference Clark and Watson2006).

Fig. 1. Best-fitting model for the entire National Comorbidity Survey, a three-factor variant of the two-factor internalizing/externalizing model. All parameter estimates are standardized and significant at p<0.05 (after Krueger, Reference Krueger1999a).

Course

Anxiety tends to have an earlier onset than depression, often beginning in childhood and being followed by adolescent depression, and adult depression being preceded by adolescent anxiety. When cases are followed into adult life, the diagnostic overlap increases dramatically between them (Pine et al. Reference Pine, Cohen, Gurley, Brook and Ma1998; Regier et al. Reference Regier, Rae, Narrow, Kaelber and Schatzberg1998; Wittchen et al. Reference Wittchen, Kessler, Pfister, Hofler and Lieb2000; Moffitt et al. Reference Moffitt, Harrington, Caspi, Kim-Cohen, Goldberg, Gregory and Poulton2007b). Anxiety and depression seem to be a risk factors for each other; in a subsample who had current co-morbid MDD and GAD in the 32-year follow-up of the Dunedin cohort (n=117), anxiety disorders preceded depression in 42%, depression coming first in 32%, and both occurring simultaneously in 26% (Moffitt et al. Reference Moffitt, Harrington, Caspi, Kim-Cohen, Goldberg, Gregory and Poulton2007b). Bittner et al. (Reference Bittner, Goodwin, Wittchen, Beesdo, Hofler and Lieb2004) show that any anxiety disorder at age 14 is a risk factor for later depression, with severe impairment being the best predictor. Beesdo et al. (Reference Beesdo, Bittner, Pine, Stein, Hofler, Lieb and Wittchen2007) confirm this for social anxiety disorder, with parental anxiety or depression and behavioral inhibition being distal risk factors, and the severity and persistence of earlier symptoms being proximal risk factors. In the Zurich prospective cohort study, co-morbid anxiety and depression is more stable than either disorder on its own, with anxiety on its own being unstable over time. Once co-morbidity develops, the probability of recurrence of either disorder alone, and particularly anxiety, is far lower than that of co-morbidity (Merikangas et al. Reference Merikangas, Zhang, Avenevoli, Acharyya, Neuenschwander and Angst2003).

The course of the emotional disorders is one of episodes of disorder followed by remission, but with high probability of relapse. The mean age of onset of anxiety disorders in the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study was 16, with depression starting on average 5 years later (Regier et al. Reference Regier, Rae, Narrow, Kaelber and Schatzberg1998), and with rates falling after age 55 (Narrow et al. Reference Narrow, Rae, Robins and Regier2002). In the UK the peak age for neurotic disorders was between 40 and 55 years, with rates falling in older age groups (Office of National Statistics, 2000). Thus, rates of recovery exceed new onsets in those above an approximate age of 50. Over a 3-year period, Lieb et al. (Reference Lieb, Zimmerman, Friis, Hofler, Tholen and Wittchen2002b) found that about half the cases of somatoform disorders remitted, but the incidence of new cases was about 26%. Female gender, lower social class, substance use, anxiety and affective disorders and also the experience of traumatic sexual and physical threat events predicted new onsets of somatoform conditions.

These disorders tend to have a relapsing course; in the large UK birth cohort that has been followed to the age of 53, 70% of adolescents who had emotional disorders at both ages 13 and 15 had mental disorders at age 36, 43 or 53, compared with about 25% of the mentally healthy adolescents (Colman et al. Reference Colman, Wadsworth, Croudace and Jones2007). Studies of single disorders tend to have a shorter follow-up period, and depend on the severity of the first episode of disorder; thus, Eaton et al. (Reference Eaton, Shao, Nestadt, Lee, Bienvenu and Zandi2008) followed first episodes of depression in a community sample for at least 13 years and showed that half had only a single episode, whereas 35% had recurrent episodes and 15% were unremitting. Brodaty et al. (Reference Brodaty, Luscombe, Peisah, Anstey and Andrews2001) followed depressives who had been admitted to hospital for 25 years, and showed that only 12% had recovered and were well whereas 84% had had recurrences. Patients attending specialist clinics for anxiety disorders have been followed for shorter periods. In the 12-year follow-up in the Harvard/Brown Anxiety Disorders Research Program (HARP), only panic disorder had a favourable course, with 82% achieving recovery, compared with 58% for GAD, 48% recovery for panic with agoraphobia and only 37% for social phobia patients. The equivalent figures for recurrences during the follow-up period are 45%, 58% and 39% respectively (Bruce et al. Reference Bruce, Yonkers, Otto, Eisen, Weisberg, Pagano, Shea and Keller2005). Major depression is not included in the HARP data set. Fergusson et al. (Reference Fergusson, Horwood and Boden2006) analysed a longitudinal study of 953 New Zealand children at ages 18, 21 and 25 years, considering the diagnoses of MDD, GAD, panic and phobias. Although a factor labelled by them as an ‘internalizing factor’ makes a substantial contribution to the longitudinal component of each disorder, there was only a disorder-specific factor in two of the disorders: MDD and phobias.

Treatment

Once more, our argument is not that there are no differences between various emotional disorders, it is that there are sufficient commonalities to conceptualize these disorders as part of a coherent spectrum. In the short term at least, all emotional disorders respond to some extent to a wide range of psychological interventions, including such simple measures as ‘case management’, with interest and concern, with regular visits and administration of a placebo tablet, as in the control arm of a randomized controlled trial. Cognitive behaviour therapy, with suitable adaptations, can be effective in all of them. Consistent with the data on the neural substrate, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are often effective in all the emotional disorders. However, a thorough meta-analysis by Furukawa et al. (Reference Furukawa, Watanabe, Omori, Goldberg, Kendler, Sirovatka and Regierin press) showed that benzodiazepines and azopirones were also equally effective in both anxious and depressive symptoms, as measured by the Hamilton scales on anxiety and depression. Studies were included if they were on the Cochrane Collaboration Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Group (CCDAN) Registers in December 2006. One possible explanation is that cases of either has some symptoms of both, alternatively it may be that any psychotropic can be shown to be superior to placebo. However, they could also be explained if the two diagnostic entities were very similar to one another.

Limitations to the validity of the cluster

Of the ‘validity criteria’ it is clear that the most important are the first four factors. In the emotional disorders, temperamental characteristics are definitely the strongest of these. However, most mental disorders also show higher negative affect than healthy controls, so even this difference is quantitative rather than qualitative. Nor should it be thought that all disorders within the cluster resemble one another closely; for example, a patient with long-standing anxiety (‘GAD’) will have a different pattern of neural activation and endocrine abnormalities than one with an acute depression (Martin & Nemeroff, Reference Martin, Nemeroff, Goldberg, Kendler, Sirovatka and Regierin press). However, they are both likely to show high negative affect, a higher familial rate of anxiety disorders, and a relatively disadvantaged early life.

Another problem is that a disorder may manifest itself differently at different ages; for example, pre-pubertal anxiety may be followed by an episode of adolescent depression, as the adolescent confronts major problems in peer popularity, educational achievement or sexual choice. Nor is there always a linear relationship between childhood problems and adult disorder; conduct problems at ages 7–9 years may be associated with increased risk for antisocial personality disorder and crime in early adulthood (ages 21–25 years), but also with adverse sexual and partner relationships (including domestic violence), early parenthood, and increased risks of substance use, mood and anxiety disorders and suicidal acts (Fergusson et al. Reference Fergusson, Horwood and Ridder2005). In the Dunedin study, for example, conduct problems at ages 11–15 were associated with increased risk for all psychiatric disorders at age 26, including internalizing problems, schizophreniform disorders and mania, in addition to broadly externalizing phenomena such as substance abuse (Kim-Cohen et al. Reference Kim-Cohen, Caspi, Moffitt, Harrington, Milne and Poulton2003).

Nor, of course, do abnormalities of personality exist on single dimensions; it is quite possible to be high on both negative emotion and low constraint, and this will influence the type of disorder developed (Krueger et al. Reference Krueger, Caspi, Moffitt, Silva and McGee1996; Krueger, Reference Krueger1999b).

It must also be conceded that the evidence presented is stronger in some areas than in others, and the differing strengths of the evidence is shown in Table 5.

Table 5. Availability of evidence over the 11 validators to support the proposed clusters

DD, Dysthymic disorder; GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; MDD, major depressive disorder; OCD, obsessive–compulsive disorder; Pan, panic disorder; Phob, phobic disorders; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; Somat, somatoform disorders.

Strength of evidence: ★, good; ✺, fair; ◆, poor or indirect; ❍, absent.

Although fairly complete arguments have been advanced for depression, GAD, panic and phobias, the evidence is patchy for PTSD and somatoform disorders, and is extremely sketchy for obsessional states and neurasthaenia. The latter two have been included because they have high scores for negative affect, and both contain a common set of non-specific emotional symptoms. There have been few objective studies of neurasthaenia as it is not recognized by the DSM system, but when it is diagnosed using the ICD-10 it falls well within the symptom complexes contained in this cluster (Ustun & Sartorius, Reference Ustun and Sartorius1995). The existing classifications are partly responsible for some of the gaps; the necessary work has often not been done.

Clinical usefulness of the proposed classification

The disorders in this cluster are all closely associated with one another, and frequently occur in combination with one another, and all respond to at least some extent to SSRIs and cognitive behaviour therapy. The most frequent example of this is the association of anxious symptoms with depressive symptoms, and a diagnosis of ‘anxious depression’ would allow clinicians to make a single diagnosis rather than declaring the patient to be ‘co-morbid’. In the National Morbidity Survey of 8580 UK respondents, Das-Munshi et al. (Reference Das-Munshi, Goldberg, Bebbington, Bhugra, Brugha, Dewey, Jenkins, Stewart and Prince2008) showed that the subsyndromal disorder allowed in the ICD-10 had a prevalence of 8.8% and accounted for 20% of all days off work in the country. Taken together with the full syndromes of anxiety and depression, differences in health-related quality of life measures between diagnostic groups were accounted for by overall symptom severity. The finding that half of the anxiety, depression and subsyndromal cases and a third of the co-morbid depression and anxiety cases grouped into a single latent class challenges the notion of these conditions as having distinct phenomenologies. Mixed presentations may be the norm in the population.

For all emotional disorders, an assessment of anxious and depressive symptoms will always be necessary. It should no longer be necessary to diagnose co-morbidity between two very different classes of disorder (e.g. depression and somatoform disorder) when both these disorders occur in the same cluster. Some treatments such as SSRIs may be generally appropriate, but other interventions, such as specific forms of counselling or cognitive behaviour therapy, may be directed at salient symptoms. The proposal would also to decrease the use of NOS (Not Otherwise Specified) categories, which are at present in frequent use.

For internists and general practitioners, the classification will simplify an otherwise confusing system, and encourage clinicians to assess anxious and depressive symptoms whenever they are faced with a patient with other psychological symptoms, or with unexplained somatic symptoms.

Conclusions

There are important differences between individual members of the emotional cluster including the fact that each disorder is defined by some symptoms that do not occur in other disorders, there are differences in cognitive and emotional processing, the neural substrate and the rates for individual disorders in FDRs. These differences should not obscure the similarities between all members of the cluster and should not necessitate putting these disorders into separate chapters of the DSM and ICD classifications.

Acknowledgement

Dr H. Mayberg kindly commented on the ‘Neural substrate’ section.

Declaration of Interest

None.