Introduction

Eating disorders (ED), both at diagnostic and subthreshold levels, are common conditions that are associated with high rates or comorbidity and relapse (Klump, Bulik, Kaye, Treasure, & Tyson, Reference Klump, Bulik, Kaye, Treasure and Tyson2009). EDs show stronger associations to mortality and quality of life impairment than other mental health conditions including schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (Crow & Smiley, Reference Crow and Smiley2010), and have an estimated annual cost of disease burden in Australia that is comparable to depression (Deloitte Access Economics, 2012), highlighting the need for effective interventions.

Although empirically-supported ED treatments exist (Linardon, Fairburn, Fitzsimmons-Craft, Wilfley, & Brennan, Reference Linardon, Fairburn, Fitzsimmons-Craft, Wilfley and Brennan2017), with up to 50% completely abstaining from core behavioral symptoms after established treatments like cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) (Linardon, Reference Linardon2018), the reality remains that fewer than 25% of affected individuals have access to appropriate care (Weissman & Rosselli, Reference Weissman and Rosselli2017). Many factors may contribute to this treatment gap, including limited therapist availability and consequently long waiting lists, cost of treatment, geographical constraints, and stigma associated with help-seeking (Kazdin, Fitzsimmons-Craft, & Wilfley, Reference Kazdin, Fitzsimmons-Craft and Wilfley2017). Solving this treatment gap likely requires multiple innovations in treatment delivery.

Technology-delivered interventions have been touted as a viable solution to the existing treatment gap. Unlike traditional face-to-face therapy, e-mental health interventions require little to no ongoing therapist input, can be delivered to a large number of people at minimal cost, are not bound by geography, and can be completed in private (Andersson, Reference Andersson2016). Recent work also indicates that a significant proportion of people with ED symptoms would prefer an e-mental health intervention over traditional face-to-face treatment (Linardon, Shatte, Tepper, & Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, Reference Linardon, Shatte, Tepper and Fuller-Tyszkiewicz2020), making it an attractive mode of intervention delivery for this population.

The potential for digital technology to reduce the widespread treatment gap has given rise to numerous e-mental health interventions for EDs. These interventions have been evaluated in numerous randomized controlled trials (RCT; de Zwaan et al. Reference de Zwaan, Herpertz, Zipfel, Svaldi, Friederich, Schmidt and Schade-Brittinger2017; Strandskov et al. Reference Strandskov, Ghaderi, Andersson, Parmskog, Hjort, Wärn and Andersson2017), with meta-analyses reporting modest reductions in ED-specific (d's = 0.43 to 0.67) and general psychopathology (d = 0.25) in individuals with diagnostic and subthreshold bulimia nervosa and binge-eating disorder (Loucas et al., Reference Loucas, Fairburn, Whittington, Pennant, Stockton and Kendall2014; Melioli et al., Reference Melioli, Bauer, Franko, Moessner, Ozer, Chabrol and Rodgers2015). Despite these notable symptom-level improvements, concerns have been raised that existing digital interventions for EDs are associated with significant attrition, with several trials reporting drop-out rates to be as high as 50% (e.g. Hotzel et al. Reference Hotzel, von Brachel, Schmidt, Rieger, Kosfelder and Hechler2014; Saekow et al. Reference Saekow, Jones, Gibbs, Jacobi, Fitzsimmons-Craft, Wilfley and Barr Taylor2015). Although better solutions are needed to minimize drop-out, the ease at which digital interventions can be scaled up and disseminated to whole populations at low cost means that a substantial proportion of affected individuals can have access to some form of help.

Most existing e-mental health interventions for EDs have been delivered through desktop computers. Thus, little attention has been devoted towards developing and evaluating smartphone app-based interventions, with the exception of three recent RCTs. In the first, Tregarthen et al. (Reference Tregarthen, Kim, Sadeh-Sharvit, Neri, Welch and Lock2019) compared the outcomes of an unselected sample randomized to either a standard (n = 1665) or tailored (n = 1629) version of a smartphone app (Recover Road) designed to address ED symptoms. The authors found no significant between-group differences in primary and secondary outcomes despite moderate within-group symptom improvement. Hildebrandt and colleagues also conducted two RCTs testing the additive effects of the self-monitoring app, Noom Monitor, to conventional CBT guided self-help for bulimia nervosa or binge-eating disorder (Hildebrandt et al., Reference Hildebrandt, Michaelides, Mackinnon, Greif, DeBar and Sysko2017, Reference Hildebrandt, Michaeledes, Mayhew, Greif, Sysko, Toro-Ramos and DeBar2020). In the earlier trial, participants randomized to CBT guided self-help + Noom Monitor (n = 33) experienced greater reductions in binge eating at post-treatment than those randomized to a guided self-help-only condition (n = 33), although no group differences emerged at follow-up (Hildebrandt et al., Reference Hildebrandt, Michaelides, Mackinnon, Greif, DeBar and Sysko2017). Hildebrandt et al. (Reference Hildebrandt, Michaeledes, Mayhew, Greif, Sysko, Toro-Ramos and DeBar2020) then compared the outcomes of those randomized to eight telemedicine CBT guided self-help sessions + Noom Monitor (n = 114) to those randomized to usual care (n = 111), finding the former group to report significantly greater post-treatment symptom reductions.

Lack of data on the acceptability and efficacy of app-based interventions is an important research gap, as smartphones are now integrated into the personal routines of most people worldwide, making them a highly appropriate mode of intervention delivery. For example, there are more than 2.7 billion smartphone users worldwide and more than 80% of users do not leave their home without their smartphone (Google, 2019). Further, smartphone interventions afford several advantages over desktop computer interventions, including the fact that because smartphones are almost always within arm's reach, users are able to practice exercises, monitor symptoms, and review content on-demand and before and after pivotal events (Heron & Smyth, Reference Heron and Smyth2010). The use of a smartphone intervention may also enable a person to practice therapeutic strategies more frequently in the natural environment, which could have a positive impact on symptom improvement given the well-documented association between skill utilization and treatment outcomes (Kazantzis et al., Reference Kazantzis, Whittington, Zelencich, Kyrios, Norton and Hofmann2016).

Since almost all existing apps for EDs that are freely available on the market do not contain components of evidence-based treatments and have not been rigorously evaluated (Fairburn & Rothwell, Reference Fairburn and Rothwell2015), we recently developed an evidence-informed, transdiagnostic, CBT-based smartphone app (‘Break Binge Eating’) for ED psychopathology and tested its acceptability and efficacy through a RCT. It was hypothesized that participants randomized to Break Binge Eating would achieve significantly greater reductions in global levels of eating disorder psychopathology and key behavioral (i.e. binge eating, compensatory behaviors) and cognitive (i.e. weight/shape concerns, dietary restraint) symptoms, as well as greater reductions in psychosocial impairment and psychological distress than participants randomized to the waitlist control. We also hypothesized that improvements would be maintained at 8-week follow-up.

Method

Design

A two-armed RCT was conducted to compare a stand-alone app with a waitlist control condition. Assessments took place at baseline, 4-weeks post-intervention, and at 8-weeks follow-up. This study received ethics approval from Deakin University and was pre-registered in the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12619001438145).

There were small deviations to the protocol. First, participants were assessed at 4 and 8 weeks rather than 6 weeks from baseline. Four weeks was instead chosen in light of recent findings demonstrating that most therapeutic change occurs just prior to the 4 week mark of treatment (Linardon, Brennan, & de la Piedad Garcia, Reference Linardon, Brennan and de la Piedad Garcia2016), while an 8 week follow-up was employed because we wanted to assess the durability of effects. Second, we removed one wellbeing secondary outcome and assessed psychological distress with the 4-item Patient Health Questionnaire rather than the 21-item Depression Anxiety Stress Scale to minimize participant burden. Third, we introduced compensatory behavior frequency as a secondary outcome due to the high frequency of such behaviors reported.

Study population and recruitment

Participants were recruited (January–May 2020) via the authors' ED-related psychoeducational platform. This platform consists of an open-access website (https://breakbingeeating.com/) and associated social media accounts. Readers may refer to Linardon, Rosato, and Messer (Reference Linardon, Rosato and Messer2020) for a detailed description of this platform. Briefly, the platform attracts more than 25 000 visits per month, with the vast majority of individuals visiting this platform for self-help content. Platform visitors are highly symptomatic, with more than 80% reporting having engaged in at least one ED behavior in the past month and ~50% exhibiting clinically significant symptoms (Linardon, Rosato, and Messer, Reference Linardon, Rosato and Messer2020). The link to this study was advertised through this platform.

Respondents to study advertisements (n = 452) first completed a brief online screening measure to determine their eligibility. Participants were eligible if they: (1) were aged 18 years or over; (2) owned a smartphone; (3) self-reported the presence of at least one objective binge eating episode over the past 4 weeks. Given that our CBT app was transdiagnostic in scope (see below), we used the presence of binge eating as the inclusion criteria because this behavior is a core symptom observed in almost all of the ED subtypes. We also included individuals who reported less than one binge eating episode a week (below the diagnostic threshold) based on prior findings showing that individuals who exhibit such subthreshold symptoms resemble those who meet full diagnostic criteria on ED and impairment measures (Crow, Stewart Agras, Halmi, Mitchell, & Kraemer, Reference Crow, Stewart Agras, Halmi, Mitchell and Kraemer2002). Participants who met the eligibility criteria went on to complete the baseline assessment.

Randomization

Randomization occurred once participants completed the baseline assessment. Randomization took place at a ratio of 1:1 and a block size of 2 using an automated computer-based random number sequence generated through Qualtrics. Upcoming allocations were concealed from the researchers and participants, as the randomization process was completely automated. In total 392 participants were randomized to the intervention (n = 197) or waitlist (n = 195) condition.

Study conditions

Intervention condition

Break Binge Eating content was hosted through schema, an open-sourced platform available on iOS and Android mobile devices (Shatte & Teague, Reference Shatte and Teague2020). Content of the app was based on Fairburn's (Reference Fairburn2008) transdiagnostic cognitive-behavioral maintenance model, with components of dissonance- and acceptance-based approaches also included. According to the cognitive-behavioral model, societal pressures for women and men to look a certain way lead a proportion of people to overvalue weight and shape and consequently engage in inflexible dietary practices. Eventually, control over eating is lost and chaotic dietary habits develop with binge eating and other compensatory behaviors. This model proposes that binge eating is further maintained by an inability to cope with sudden mood shifts. Interventions are thus directed towards normalizing eating behavior, reducing the importance placed on weight and shape, and promoting adaptive emotion regulation strategies (Fairburn, Reference Fairburn2008).

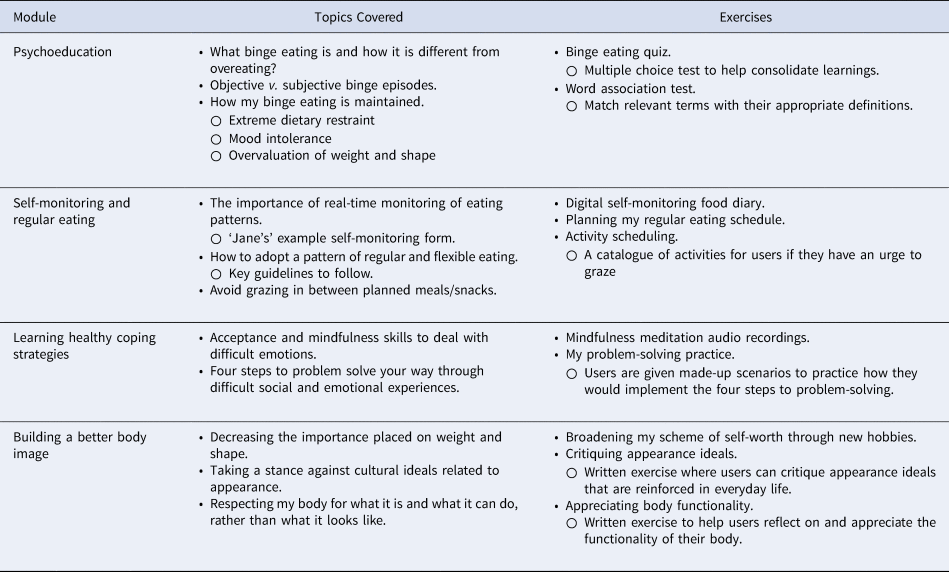

The Break Binge Eating app comprised four modules. Each module took around 30–90 min to complete as participants were presented with up to 10 short audio recordings (~5 min each) per module, were presented with text-based reading material, and were required to complete various short activities to help maintain progress. The first module was psychoeducational in nature, while the remaining modules were designed to target the core symptoms. Participants worked through the modules sequentially and a subsequent module unlocked when the prior module was completed. Self-observation was a key component of this app. A digital diary was introduced in Module 2 for participants to monitor their daily eating patterns. Automated feedback was also presented for participants to observe their reported binge eating frequency and fluctuations in other key symptoms over the preceding 10 days. A description of the modules is presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Description of the modules of the break binge eating app

The app was designed to be self-guided. Participants were instructed to go at a pace that suited them, although they were encouraged to practice the prescribed exercises daily throughout the 8 weeks. Participants were sent weekly reminder emails. The app also prompted participants daily to encourage self-monitoring.

Control condition

Waitlist participants completed the same assessments at baseline, post-test, and follow-up. Waitlist participants were given access to the app 4 weeks post-randomization.

Study assessments

Participant characteristics

At baseline, we asked participants to indicate their age, height and weight, gender, relationship status, ethnic background, the highest level of education, country of residence, whether they had ever been diagnosed with an ED by a mental health professional, whether they have a current ED diagnosis, whether they have previously been or are currently diagnosed with another mental health disorder by a health professional, whether they have previously received or are currently receiving treatment for an ED, and their therapy modality preference (face-to-face therapy or digital therapy with or without support). Motivation and perceived confidence to change were also assessed through a single item.

Primary outcome

The pre-registered primary outcome was the global score derived from the 28-item Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q), which is a measure of core attitudinal and behavioral ED symptoms (Fairburn & Beglin, Reference Fairburn and Beglin1994). A global score is calculated by combining the four EDE-Q subscales, which includes items that are rated along a 7-point scale. Scores are averaged to produce scale scores, with higher scores reflecting more severe ED symptoms. Cronbach's α was 0.90.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes included the shape concern (α = 0.85), weight concern (α = 0.71), eating concern (α = 0.75), and dietary restraint (α = 0.77) subscales of the EDE-Q, and items assessing the frequency of objective and subjective binge eating episodes experienced over the past month. Compensatory behavior frequency was assessed via averaging the frequency of self-induced vomiting, laxative use, and driven exercise episodes. The 16-item Clinical Impairment Assessment (CIA; Bohn et al., Reference Bohn, Doll, Cooper, O'Connor, Palmer and Fairburn2008) was also used to assess psychosocial impairment (α = 0.93), and the Patient Health Questionnaire–4 (Kroenke, Spitzer, Williams, & Löwe, Reference Kroenke, Spitzer, Williams and Löwe2009) was used to assess depressive (α = 0.84) and anxiety (α = 0.84) symptoms.

Intervention acceptability

App acceptability questions included (a) whether the participant would recommend the app; (b) perceived usefulness of the app, (c) ratings of perceived engagement, and (d) satisfaction levels.

Sample size calculation

The required sample size was powered with the following assumptions: (1) a small group difference (d = 0.35) between the intervention and wait-list control groups for the post-test outcomes; (2) power set at 0.80; (3) alpha set at 0.05 (two-tailed); (4) expected attrition rate of 25% based on the most recent meta-analytic estimates observed in digital intervention trials for EDs (Linardon, Shatte, Messer, Firth, & Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, Reference Linardon, Shatte, Messer, Firth and Fuller-Tyszkiewiczin press); and (5) an allocation ratio of 1:1. Under these assumptions, the target sample size at baseline was 173 for each group.

Statistical analyses

Analyses were undertaken using Stata version 16, and conducted on an intention-to-treat basis, with participant data included as per initial group allocation. Linear mixed models were used for all outcome measures, and repeated measures clustered within individuals.

Models are reported in adjusted form, using covariates identified a priori: age, BMI, sex, current ED treatment, confidence and motivation to change, and current depressive and anxiety disorder. These covariates were selected in light of earlier research demonstrating that each of these baseline variables are predictive of treatment outcomes during CBT for EDs (for a review, see Linardon, de la Piedad Garcia, & Brennan, Reference Linardon, de la Piedad Garcia and Brennan2016). Effect sizes are reported as standardized mean differences, with values of ⩽0.20 considered small, 0.50 moderate, and ⩾0.80 considered large (Cohen, Reference Cohen1992).

In these models, missing data were handled using multiple imputations with 50 imputations. However, as this approach makes an untestable assumption that missingness is ignorable, sensitivity analyses were conducted to evaluate the robustness of the observed results to the possible presence of non-ignorable patterns of missingness (not missing at random; NMAR). Pattern mixture models via the mimix package (Cro, Morris, Kenward, & Carpenter, Reference Cro, Morris, Kenward and Carpenter2016) were used to conduct the sensitivity analyses. Several plausible NMAR patterns were tested with mimix:(1) last mean carried forward (LMCR), which imputes the mean at the previous time-point from one's assigned group; (2) jump to reference (J2R), in which an individual's missing data is imputed with the mean value from the control group at that time-point; and (3) copy increments in reference (CIR), in which an individual's missing data is imputed with the mean increment from the previous time-point for the control group regardless of treatment assignment. Fifty imputations were also undertaken per model.

Changes in outcomes from post-intervention to follow-up were evaluated using linear mixed-effects. Multiple imputations (n = 50 imputations) was used to handle missing data.

Results

Participants

A total of 452 people expressed interested in this study (Fig. 1); 14 did not meet inclusion criteria and 46 were no longer interested or did not complete the baseline assessment. The total number of participants randomized was 392.

Fig. 1. Flow of participants throughout the study.

Baseline characteristics

Table 2 presents the baseline characteristics. Most participants were female, Caucasian did not have a current diagnosis of an ED or other mental health conditions, were not currently receiving treatment for an ED, and expressed a preference for a guided digital intervention.

Table 2. Baseline characteristics of randomized participants

Test statistic represents t test (Cohen's d) for continuous variables and chi square (Cramér's V) for categorical variables; none of the test statistics are statistically significant.

The sample was highly symptomatic; 42% exhibited symptoms that resembled bulimia nervosa, 31% exhibited symptoms that resembled binge-eating disorder, and the mean EDE-Q global score for the entire sample was nearly two standard deviations above community norms (Mond, Hay, Rodgers, & Owen, Reference Mond, Hay, Rodgers and Owen2006). Only 18 (4%) participants reported less than four binge eating episodes the past month (below the diagnostic cut-off).

The two groups were compared on baseline variables. No significant baseline differences emerged on any variable, except for EDE-Q eating concern subscale scores. The intervention group reported significantly higher eating concern scores than the control group (p = 0.016), although the effect size was small (d = 0.25).

Attrition

A total of 252 participants (64%) provided post-test data and 132 participants (33%) provided follow-up data. The intervention group was associated with significantly higher post-test attrition rates than the control group (n = 101 v. n = 39; χ2 = 41.73, p < 0.001; Cramér's V = 0.32). However, condition was not associated with attrition rates at follow-up (n = 129 v. n = 131; χ2 = 0.13, p = 0.722; Cramér's V = 0.02).

Dropouts were compared with completers on baseline variables. Post-test dropouts were younger (t = 2.72, p = 0.007; d = 0.29) and were less likely to have a tertiary degree (χ2 = 7.57, p = 0.006; Cramér's V = 0.02) than completers. Dropouts at follow-up were younger than study completers (t = 3.80, p < 0.001; d = 0.42).

App usage

The majority of participants downloaded the app immediately after randomization (n = 167; 85%). The percentage who completed each of the Modules and the total number of Module views were: Module 1 (n = 123 completed; 62%; M views = 7.95, s.d. = 4.80); Module 2 (n = 63 completed; 32%; M views = 18.96, s.d. = 49.91); Module 3 (n = 32 completed; 16%; M views = 3.74, s.d. = 5.27); Module 4 (n = 19 completed; 10%; M views = 1.00, s.d. = 2.60). The mean number of times the app was viewed was 133.78 (s.d. = 176.64) and the mean number of days the app was opened was 13.34 (s.d. = 13.08).

As expected, relative to study completers, those who dropped out were less likely to have downloaded the app (χ2 = 25.06, p < 0.001; Cramér's V = 0.35), were less likely to have logged into the app (t = 5.26, p < 0.001, d = 0.77), had fewer days with which they opened the app (t = 6.54, p < 0.001, d = 0.98), and completed fewer modules (t = 6.33, p < 0.001, d = 0.96).

Intervention efficacy at post-test

Primary outcome

The adjusted mean difference in EDE-Q global scores between the intervention and control condition was statistically significant with a large effect size (d = −0.80). The intervention group reported significantly greater reductions in EDE-Q global scores than the control group (Table 3).

Table 3. Means, standard deviations, and change scores on primary and secondary outcomes for study conditions

CIA, Clinical Impairment Assessment; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire.

Covariates were age, BMI, sex, current ED treatment, confidence, motivation, current depressive and anxiety disorder. M and s.d. values are based on non-imputed data; mean differences and effect sizes are derived from ITT analysis (n = 392) using multiple imputations.

Secondary outcomes

There were significant adjusted mean differences between the intervention and control condition in weight concerns (d = −0.57), shape concerns (d = −0.74), eating concerns (d = −0.71), dietary restraint (d = −0.57), objective binge episodes (d = −0.51), subjective binge episodes (d = −0.30), psychosocial impairment (d = −0.67), and depressive (d = −0.47) and anxiety (d = −0.46) symptoms. A small, non-significant effect was observed for compensatory behavior frequency (d = −0.14).

Sensitivity Analyses. Analyses on post-test outcomes were re-run in a series of sensitivity analyses using different methods to handle data that were potentially NMAR (LMCF; J2R; CIR). Most results were largely unchanged and remained statistically significant with a few exceptions: between-group differences in subjective binge eating became non-significant in the LMCF and CIR models, and objective binge episodes, depressive symptoms, and anxiety symptoms became non-significant in CIR models (see online Supplementary Materials).

Intervention efficacy at follow-up

Eight-week follow-up data are presented in Table 4. EDE-Q global scores significantly reduced further from post-test to follow-up (d = −0.25), while non-significant post-test to follow-up effects were observed for remaining outcomes, indicating that initially achieved changes from baseline to post-intervention were sustained over time. For those allocated to the waiting list, significant improvements from the post-test (at which point they received the app) to follow-up point were observed for all outcomes except subjective binge eating, compensatory behaviors, and depressive symptoms.

Table 4. Change scores from post-test to follow-up

CIA, Clinical Impairment Assessment; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire.

Notes: Covariates were age, BMI, sex, current ED treatment, confidence, motivation, current depressive and anxiety disorder. Note that at the post-test period, control group participants received access to the app, and so the follow-up point represents 4 weeks of app usage for this group.

Acceptability

Online Supplementary Table S2 presents app acceptability data. From 153 participants, 92% would recommend the app to others. Module 2 was perceived to be most helpful (62%) and the daily food diary was the exercise perceived to be most helpful (50%). For further acceptability indices, refer to online Supplementary Materials.

Discussion

This study evaluated the efficacy of a CBT-based app for ED psychopathology through a RCT design. Findings showed that participants were overall satisfied with the app and perceived many of the modules and exercises to be helpful, suggesting that this intervention is well tolerated and accepted among the target population. The intervention outperformed the control group on primary and secondary outcomes (except compensatory behavior frequency), indicating that this app can effectively target the core symptoms of EDs and associated impairment. Crucially, improvements on all outcome measures were sustained over the course of the trial period, highlighting the durability of intervention effects.

The effect sizes observed from our self-guided app were comparable to the effect sizes reported in previous RCTs of therapist-guided computerized interventions for EDs (e.g. Sánchez-Ortiz et al., Reference Sánchez-Ortiz, Munro, Stahl, House, Startup, Treasure and Schmidt2011; Wagner et al., Reference Wagner, Nagl, Dölemeyer, Klinitzke, Steinig, Hilbert and Kersting2016). This was surprising given that digital interventions with added therapist guidance tend to produce larger effects than pure self-guided digital interventions (Linardon, Cuijpers, Carlbring, Messer, & Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, Reference Linardon, Cuijpers, Carlbring, Messer and Fuller-Tyszkiewicz2019). There may be several explanations for this, the first being that the contents of our app were largely based upon the principles, techniques, and assumptions of transdiagnostic CBT-E for EDs (Fairburn, Reference Fairburn2008). The model that underpins CBT-E has been rigorously evaluated (Pennesi & Wade, Reference Pennesi and Wade2016), has been adapted to reflect advances in knowledge, and provides the foundation for a course of treatment that has been shown to produce larger symptom improvements than other treatment approaches (Linardon, Wade, De la Piedad Garcia, & Brennan, Reference Linardon, Wade, De la Piedad Garcia and Brennan2017). A second explanation for the large effect sizes was that, when designing this trial, we ensured to incorporate (where feasible) variables known to bolster the efficacy of app-based interventions highlighted in a recent meta-analysis, including interactive CBT app elements and regular prompts to engage (Linardon et al., Reference Linardon, Cuijpers, Carlbring, Messer and Fuller-Tyszkiewicz2019).

As with all trials of e-mental health interventions, issues with attrition were noted. The attrition rate at post-test was 35%, with this estimate almost doubling at follow-up. Although these attrition estimates were noticeably lower than those reported in several other mental health app trials (Arean et al., Reference Arean, Hallgren, Jordan, Gazzaley, Atkins, Heagerty and Anguera2016; Mak et al., Reference Mak, Tong, Yip, Lui, Chio, Chan and Wong2018), they were still relatively high and warrant comment. There are two possible reasons for the observed attrition rate. First, participants could enrol and complete this trial entirely online, meaning that there was no need to come into contact with the researchers. This is important, as attrition in app trials is substantially higher when participants complete the trial online rather than when they are required to undergo telephone or in-person interviews with the researchers (Linardon & Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, Reference Linardon and Fuller-Tyszkiewicz2020). Enrolment methods that require personal contact with the researchers may maximize retention because it attracts more motivated participants and allows expectations to be clarified between participant and researcher (Linardon & Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, Reference Linardon and Fuller-Tyszkiewicz2020). A second reason for the observed attrition rates was that we did not offer participants reimbursement for remaining in the trial, which has been shown experimentally to enhance retention (Khadjesari et al., Reference Khadjesari, Murray, Kalaitzaki, White, McCambridge, Thompson and Godfrey2011). We should note, however, that the choice of these methodological features enhanced the external validity of our findings, as users of mental health apps in ‘real world’ settings are not required to undergo screening interviews nor are they reimbursed for engagement.

The difficulty in sustained app engagement is well-known (Torous, Nicholas, Larsen, Firth, & Christensen, Reference Torous, Nicholas, Larsen, Firth and Christensen2018). Our observed engagement rates were less than optimal, with a noticeable proportion of participants not completing all required modules. This finding highlights the importance of identifying and applying strategies designed to better engage end-users and enhance app adherence, particularly since there appears to be a dose-response relationship between online intervention engagement and outcomes (Donkin et al., Reference Donkin, Christensen, Naismith, Neal, Hickie and Glozier2011). Although we sought to enhance engagement through regular reminder emails and through the app prompting participants to monitor their daily symptoms and food intake, it is likely that more effective retention strategies are needed to enhance user engagement. One promising strategy may involve gathering detailed qualitative feedback from the target population on the usability of this app, as this would allow us to modify the content, layout, and functionality of the app in a way that ensures we are meeting the preferences of the end-user (Fuller-Tyszkiewicz et al., Reference Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, Richardson, Klein, Skouteris, Christensen, Austin and Arulkadacham2018; Shatte, Hutchinson, & Teague, Reference Shatte, Hutchinson and Teague2019).

The current findings highlight the potential for the many ways through which this smartphone app could be incorporated within existing models of mental health care delivery for EDs. For instance, this app may be well-suited to the stepped-care model, in which an inexpensive and low-intensity intervention like this is offered as a first-step in treatment, with more intensive resources reserved for those who fail to respond after a certain period of time (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Cacioppo, Fettich, Gallop, McCloskey, Olino and Zeffiro2016). Apps, in particular, may be a palatable first step for those who are concerned about seeking help, as they enable people to approach treatment at an individualized pace (Juarascio, Manasse, Goldstein, Forman, & Butryn, Reference Juarascio, Manasse, Goldstein, Forman and Butryn2015). Alternatively, this brief app could be prescribed to people to put on a waiting list for specialized treatment as a way to prevent drop-out, maintain motivation, and alleviate symptoms that warrant immediate attention. Finally, this app could also be used alongside standard treatment, enabling clients to more regularly and efficiently practice certain therapeutic skills in between sessions (Juarascio, Parker, Lagacey, & Godfrey, Reference Juarascio, Parker, Lagacey and Godfrey2018). Although apps like these are not intended to replace routine clinical services, their capacity to be flexibly integrated within current models of mental health care delivery may prove vital for reducing the existing treatment gap and better addressing the unmet needs of people with EDs.

Despite several key strengths to this study, there are limitations to consider. First, the use of a waitlist control is a limitation. A wait-list may be a weak comparator because it does not control for non-specific factors and may thus overestimate the efficacy of an online intervention (Linardon, Reference Linardon2020). Second, outcome assessments are derived from participant self-report. Although self-report scales are widely used in RCTs, it is possible that self-report scales may be associated with an overestimation of symptom improvement. However, the use of online self-report scales enabled us to obtain an adequately powered sample and provide anonymity for those who would otherwise not participate if contact with the researchers was required. Third, we did not gather qualitative feedback on the app. Such feedback would have been useful for better understanding of potential reasons for drop-out or poor engagement from the perspective of the end-user. Fourth, we acknowledge that this trial was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic. As COVID-19 has led to the disruption of face-to-face services and escalation of ED symptoms (Phillipou et al., Reference Phillipou, Meyer, Neill, Tan, Toh, Van Rheenen and Rossell2020), it is possible that the current sample was more symptomatic and motivated to engage in an online intervention than prior samples, thus affecting the generalizability of findings.

In conclusion, this study adds nascent literature regarding the empirical status and clinical utility of smartphone apps for ED psychopathology. A stand-alone, self-guided, CBT-based app lead to significant short- and longer-term improvements in ED psychopathology, impairment and distress. Findings highlight the potential for this smartphone app to serve as a cost-effective and easily accessible intervention for those who cannot – or are waiting to – receive standard treatment.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720003426

Acknowledgements

This research received funding from Deakin University.

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.