Prevalence estimates do not exist for all eating disorders published in the fifth revision of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM-5) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Adolescent research of this kind is particularly lacking, despite this being the age during which eating disorders typically emerge (Volpe et al., Reference Volpe, Tortorella, Manchia, Monteleone, Albert and Monteleone2016). Among the changes made to the eating disorders chapter in the DSM-5 is the replacement of the problematically dominant (Le Grange et al., Reference Le Grange, Swanson, Crow and Merikangas2012) ‘not otherwise specified’ (EDNOS) residual diagnosis with two residual categories, ‘other specified’ (OSFED) and ‘unspecified’ (UFED) feeding and eating disorders. Adult prevalence studies suggest that DSM-5 residual diagnoses remain up to 6 times more common than criterial eating disorders (Hay et al., Reference Hay, Mitchison, Collado, González-Chica, Stocks and Touyz2017), however whether this is true in adolescents remains largely unknown.

The five OSFED syndromes include atypical (non-underweight) anorexia nervosa (AN), subthreshold bulimia nervosa (SBN), subthreshold binge eating disorder (BED), purging disorder (PD), and night eating syndrome (NES). Although the DSM-5 put forward these syndromes in order to stimulate further research into their clinical utility, very little research of this kind has been executed. This includes no population prevalence estimates for NES, in adults or adolescents, and no analysis of the prevalence of all five syndromes within the one study, which is needed to facilitate diagnostic comparisons. Especially important will be the elucidation of the burden and distribution of these syndromes during adolescence, a time of intense fluctuation in disordered eating (Patton et al., Reference Patton, Coffey, Carlin, Sanci and Sawyer2008).

Most adolescent prevalence studies have used female samples (e.g. Stice et al., Reference Stice, Marti and Rohde2013; Glazer et al., Reference Glazer, Sonneville, Micali, Swanson, Crosby, Horton, Eddy and Field2019). However, evidence that males constitute a substantial minority of eating disorder cases (Murray et al., Reference Murray, Nagata, Griffiths, Calzo, Brown, Mitchison, Blashill and Mond2017), and are over-represented in residual eating disorder diagnoses (Le Grange et al., Reference Le Grange, Swanson, Crow and Merikangas2012), signals the need to ensure that future studies are representative across gender. Three mixed gender population studies were found that have estimated the point prevalence of individual DSM-5 OSFED syndromes in adolescents (Allen et al., Reference Allen, Byrne, Oddy and Crosby2013; Micali et al., Reference Micali, Solmi, Horton, Crosby, Eddy, Calzo, Sonneville, Swanson and Field2015; Hammerle et al., Reference Hammerle, Huss, Ernst and Bürger2016). In an Australian longitudinal study of >1300 adolescents, atypical anorexia was identified in 0.3 and 0.9% of boys and girls at age 14, and no boys or girls at age 17 (Allen et al., Reference Allen, Byrne, Oddy and Crosby2013). PD was relatively more stable, found in 0.4 and 2.7% of boys and girls at age 14, and 0.6 and 2.1% at age 17, respectively. In a German study of >1600 German early-adolescents, 3.6 and 1.9% of the participants were identified with atypical anorexia nervosa (AAN) and PD, respectively, however no participants were identified with SBN nor subthreshold BED (Hammerle et al., Reference Hammerle, Huss, Ernst and Bürger2016). A larger study, of >6000 14 year-olds and >5000 16 year-olds in the US found estimates of 0.4, 1.3 and 0.03% for PD, SBN and subthreshold BED, respectively, among 14 year-olds, and 1.5, 3.2 and 0.4%, respectively, among 16 year-olds (Micali et al., Reference Micali, Solmi, Horton, Crosby, Eddy, Calzo, Sonneville, Swanson and Field2015). Together these reports demonstrate that OSFED is likely to be more prevalent than any and all of the DSM-5 criterial eating disorders in adolescence, with point prevalence estimates for AN ranging from 0.1–2.5%, for BN 0.3–1.6%, and for BED 0.5–1.2% (Allen et al., Reference Allen, Byrne, Oddy and Crosby2013; Flament et al., Reference Flament, Buchholz, Henderson, Obeid, Maras, Schubert, Paterniti and Goldfield2015; Micali et al., Reference Micali, Solmi, Horton, Crosby, Eddy, Calzo, Sonneville, Swanson and Field2015; Hammerle et al., Reference Hammerle, Huss, Ernst and Bürger2016).

The restriction of the above studies to particular adolescent age cohorts (e.g. ‘early adolescents’, 16 year-olds) may have limited what could be learned regarding the pattern of criterial and residual eating disorder occurrence across the adolescent period. Further, while it is known that adults with eating disorders have a greater likelihood of obesity (Hay et al., Reference Hay, Mitchison, Collado, González-Chica, Stocks and Touyz2017), we know little about the association between weight status and DSM-5 eating disorders during adolescence. Although the study by Micali et al. (Reference Micali, Solmi, Horton, Crosby, Eddy, Calzo, Sonneville, Swanson and Field2015) found an increased risk for being overweight or obese after two years among 14 year-olds with BN and BED, arguably obese status should be separated from overweight status given the lack of a clear association with health impairment found to be associated with the latter in adolescents (Halfon et al., Reference Halfon, Larson and Slusser2013).

There is continuing concern regarding the challenge of overdiagnosis (‘diagnostic inflation’), suggested to be unhelpful or at worst harmful to individuals and the health system (Frances, Reference Frances2013; Moynihan et al., Reference Moynihan, Barratt, Buchbinder, Carter, Dakin, Donovan, Elshaug, Glasziou, Maher, Mccaffery and Scott2018). Although Frances argues that the cause of this within psychiatry is the lack of a ‘bright line separating the worried well from the mildly mentally disordered’ in the DSM-5, it could be countered that the clinical significance criterion is intended to act precisely as this theoretical line. This criterion, requiring symptoms to be associated with distress and/or impairment, has the express purpose of reducing the over-pathologizing of symptomatic yet relatively unimpaired individuals, especially in epidemiological studies (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). However, a minority of disorders do not include this criterion – and eating disorders are a notable exception. Neither AN nor BN includes the clinical significance criterion, whereas BED requires marked distress but not functional impairment. A possible reason for this may relate to ego-syntonicity and favorable regard for eating disorder-related weight loss, particularly in AN, which may impede assessment of distress and impairment (Jenkins et al., Reference Jenkins, Hoste, Meyer and Blissett2011). On the other hand, the omission of a criterion for clinical significance has implications regarding epidemiological and health burden assessment (Beals et al., Reference Beals, Novins, Spicer, Orton, Mitchell, Baron and Manson2004), and may explain the criticism of the DSM-5 inclusion of BED (Frances, Reference Frances2013). This issue may be most problematic in adolescent populations, given the high level of fluctuation in the onset and spontaneous remission of disordered eating at this time (Patton et al., Reference Patton, Coffey, Carlin, Sanci and Sawyer2008). Thus, estimating the extent to which meeting symptomatic criteria for an eating disorder during adolescence is associated with significant distress and/or impairment will be useful to inform the extent of overdiagnosis in eating disorder epidemiology. Further, there is ambiguity as to the role of the clinical significance criterion in the other/unspecified eating disorders. While it appears in the definition of UFED and a general statement suggests its need for the OSFED disorders, only NES explicitly references distress and impairment in its description of symptoms (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Thus, research that evaluates the inclusion of the clinical significance criterion in OSFED will also contribute to the evidence-base aiding decisions about the future status of these syndromes in the DSM and their diagnostic criteria.

Aims

This study aimed to report up-to-date prevalence estimates for the full range of DSM-5 eating disorders in a large general population sample of Australian adolescent boys and girls aged 12–19, including first-time estimates for all five OSFED syndromes. Further, this study aimed to examine, for the first time, the impact of applying the criterion for clinical significance on these prevalence estimates.

Method

Sampling procedure and participants

Data were used from the baseline survey of the EveryBODY Study, a longitudinal investigation of eating disorders among Australian adolescents. Sampling procedures have been detailed elsewhere (Trompeter et al., Reference Trompeter, Bussey, Hay, Mond, Murray, Lonergan, Griffiths, Pike and Mitchison2018). In brief, four independent and nine government schools, from a broad range of socioeconomic advantage, participated. All parents and students received information about the study over a period of 4 weeks using multiple methods of dissemination, and a passive parental consent procedure was used, whereby parents could opt out their child from the study. Students who provided assent were given the online survey to complete at school. Participants were offered the chance to enter a prize draw to win one of 10 gift vouchers, and the schools received a general wellbeing report based on their students' data. The study was approved by the Macquarie University Human Research Ethics Committee and the New South Wales Department of Education.

Measures

Sociodemographic questions

Participants were asked demographic questions including age, school grade, gender, sex, country of birth, and postcode (which was later converted to a socio-economic index for area (SEIFA) score).

Eating disorder diagnoses

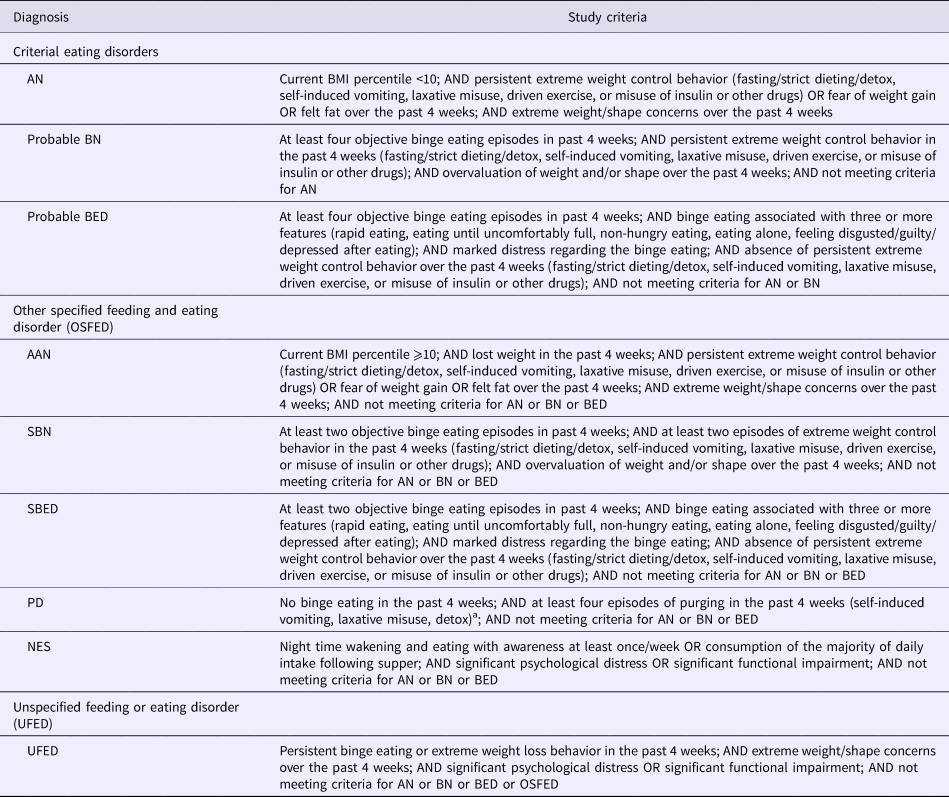

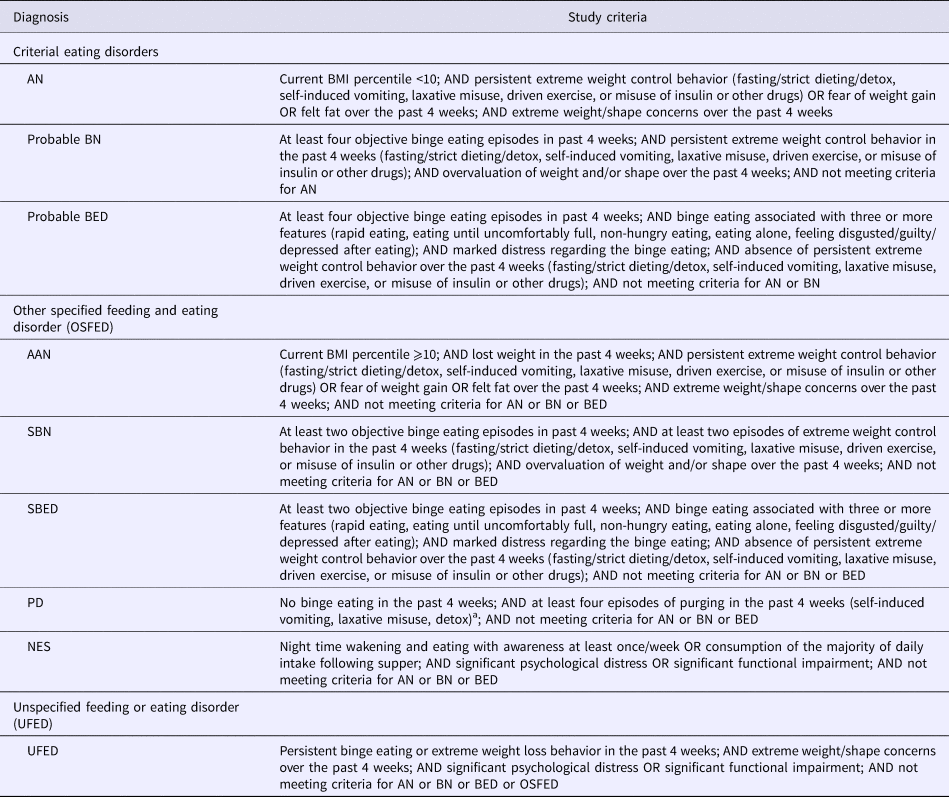

Table 1 provides the operationalization of the diagnostic criteria. Most symptoms were captured by items of the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q), which assesses the presence and severity of cognitive and behavioral eating disorder symptoms and features (Fairburn and Beglin, Reference Fairburn, Beglin and Fairburn2008). This questionnaire has previously been validated in Australian adolescents boys and girls and demonstrates sound reliability (Mond et al., Reference Mond, Hall, Bentley, Harrison, Gratwick-Sarll and Lewis2014). Items used in this study included the behavioral frequency items (self-induced vomiting, laxative misuse, driven exercise, and binge eating), and the Likert-type items that comprise the combined weight and shape concern subscales. As the frequency of behaviors was only assessed over the past one month (not the three months duration required for BN and BED), we use the term ‘probable’ for these diagnoses. McDonald's omega for the combined weight and shape concern subscale in the present study was 0.96 and 0.94 for girls and boys, respectively.

Table 1. Operationalization of DSM-5 eating disorder diagnoses

a Frequency of purging based on the PD criteria suggested by Keel and Striegel-Moore (Reference Keel and Striegel-Moore2009)

Participants self-reported current weight and height, which was converted to age and gender-adjusted body mass index (BMI) percentiles for children and adolescents. A BMI percentile <10 was used for the underweight criterion of AN, as this cut-off has most frequently been used in adolescent epidemiological studies of DSM-5 AN (Allen et al., Reference Allen, Byrne, Oddy and Crosby2013; Rojo-Moreno et al., Reference Rojo-Moreno, Arribas, Plumed, Gimeno, Garcia-Blanco, Vaz-Leal, Luisa Vila and Livianos2015; Hammerle et al., Reference Hammerle, Huss, Ernst and Bürger2016; Nagl et al., Reference Nagl, Jacobi, Paul, Beesdo-Baum, Hofler, Lieb and Wittchen2016). Three items from the Night Eating Questionnaire (NEQ) (Allison et al., Reference Allison, Lundgren, O'reardon, Martino, Sarwer, Wadden, Crosby, Engel and Stunkard2008) were used to assess symptoms of NES, including a proportion of daily food intake consumed following supper, nocturnal eating (eating after going to bed), and awareness during nocturnal eating. The NEQ has been validated in adolescents and is superior to parent report (Gallant et al., Reference Gallant, Lundgren, Allison, Stunkard, Lambert, O'loughlin, Lemieux, Tremblay and Drapeau2012a).

Several additional questions were developed by the researchers to capture frequency of additional extreme weight control behaviors (fasting, strict dieting, detoxes, insulin misuse, other drug use for weight loss), distress associated with binge eating, and additional diagnostic BED features (e.g. eating faster than usual, eating alone due to embarrassment). Participants were also asked about any recent weight loss in the past 4 weeks to assess AAN.

Clinical significance

Scores from the K10 Psychological Distress Scale (K10) (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Andrews, Colpe, Hiripi, Mroczek, Normand, Walters and Zaslavsky2002) and the Pediatric Quality of Life Scale (PedsQL) SF15 (Varni et al., Reference Varni, Seid and Kurtin2001; Varni et al., Reference Varni, Burwinkle, Seid and Skarr2003) were used to measure clinically significant distress and functional impairment, respectively. The K10 measures the frequency of anxiety and depressive symptoms during the past 4 weeks using 10 Likert-type items. Scores range from 10 to 50, with higher scores indicating higher levels of distress. The K-10 has demonstrated high internal consistency and validity in predicting clinically significant levels of distress in general population samples (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Andrews, Colpe, Hiripi, Mroczek, Normand, Walters and Zaslavsky2002). McDonald's omegas for the K-10 in girls and boys in the present study were 0.94 and 0.93, respectively.

The 12 items from the physical functioning, emotional functioning, and social functioning subscales of the PedsQL SF15 (Varni et al., Reference Varni, Seid and Kurtin2001, Reference Varni, Burwinkle, Seid and Skarr2003) were included in the survey. Items ask participants to indicate on a Likert type scale how true a series of statements are of them in the past 4 weeks. Scores are reversed and transformed on a 0–100 scale, such that higher scores indicate higher functioning. Subscale scores are derived as the mean of the items for that scale. For this study we combined the emotional and social functioning scales to create a psychosocial subscale. The PedsQL SF15 has evidence of good reliability and validity in previous studies of adolescents (Varni et al., Reference Varni, Burwinkle, Seid and Skarr2003). McDonald's omegas in the current study sample for the physical functioning subscale was 0.86 and 0.87 for girls and boys respectively, and for the psychosocial functioning subscale was 0.90 and 0.91 for girls and boys respectively.

Since clinical significance as a diagnostic criterion has not been operationalized previously for eating disorders, we tested two definitions: (1) Lenient definition: K-10 score >15 (indicative of moderate to severe distress) and/or PedsQL (physical or psychosocial subscale score) ⩽1 s.d. below the sample mean; (2) Stringent definition: K-10 score ⩾30 (severe distress) and/or PedsQL (physical or psychosocial subscale score) ⩽1 s.d. below the sample mean. These K-10 cut-offs have been used previously in population-based studies (Andrews and Slade, Reference Andrews and Slade2001; Varni et al., Reference Varni, Burwinkle, Seid and Skarr2003), and the PedsQL cut-off is more conservative than cut-offs used previously to identify children with special health care needs and chronic conditions (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Thompson, Chi, Knapp, Revicki, Seid and Shenkman2009).

Statistical analysis

Data were weighted according to the 2016 Census gender distribution information for adolescents in New South Wales, Australia (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2017). Prevalence estimates were calculated, and a series of χ2 tests with Bonferroni-adjusted post-hoc Z-tests were conducted to compare the prevalence by gender. To assess the relationship between diagnosis and odds of falling within the underweight (BMI<5th percentile), overweight (85th percentile⩽BMI<95th percentile) or obese (BMI ⩾95th percentile) weight categories (relative to healthy weight; 5th percentile⩽BMI<85th percentile), a series of binary multivariate logistic regressions were employed, adjusting for age, gender, socioeconomic status and migrant status. Additional binary multivariate logistic regressions were employed to examine the odds of meeting criteria for each eating disorder according to socioeconomic status, school year, and migrant status, adjusted for gender and BMI percentile. Finally, descriptive analyses were conducted to determine the prevalence of eating disorder diagnoses after applying criteria for clinical significance.

Results

Participant characteristics

On average, 70% of students at each school participated in the study, and data were collected from N = 5191 students. Of these, n = 119 were excluded due to completion of <10% of the survey (n = 39), non-serious responses to open-ended questions (n = 79), and withdrawn consent (n = 1), leaving a total sample of N = 5072 students between 11–19 years (mean age = 14 years and 11 months). Data in this study were from the participants who completed the relevant measures for each analysis. Little's MCAR Test demonstrated that data were not missing at random, p < 0.001. Participants with missing data had similar distributions to participants with complete data for gender identity (p = 0.33) and migrant status (p = 0.09), but on average were in a slightly higher grade at school (M = 3.3, s.d. = 1.8 v. M = 3.0, s.d. = 1.5; t (5069) = 4.0, p < 0.001), and had a slightly lower socioeconomic status (M = 977.1, s.d. = 39.6 v. M = 985.5, s.d. = 41.9; t (4955) = −4.4, p < 0.001). Of the included participants, 49.2% identified as male, 48.4% identified as female, and 2.4% identified as ‘other’ (75.2% of participants identifying as ‘other’ gender reported biological sex as male). Lower school grades were over-represented, with 41.7% in grades 7–8, 39.7% in grades 9–10, and 18.6% were in grades 11–12. Most participants were born in Australia (88.2%).

Prevalence of eating disorders by gender

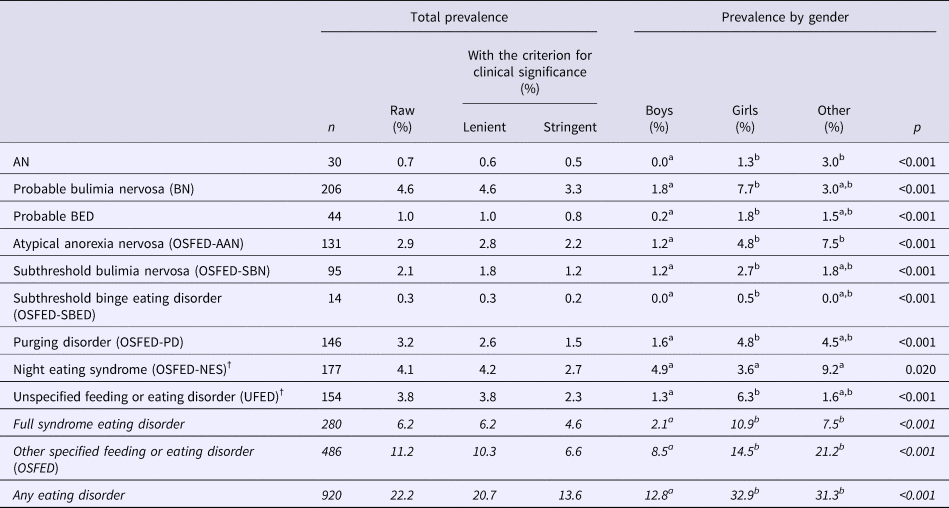

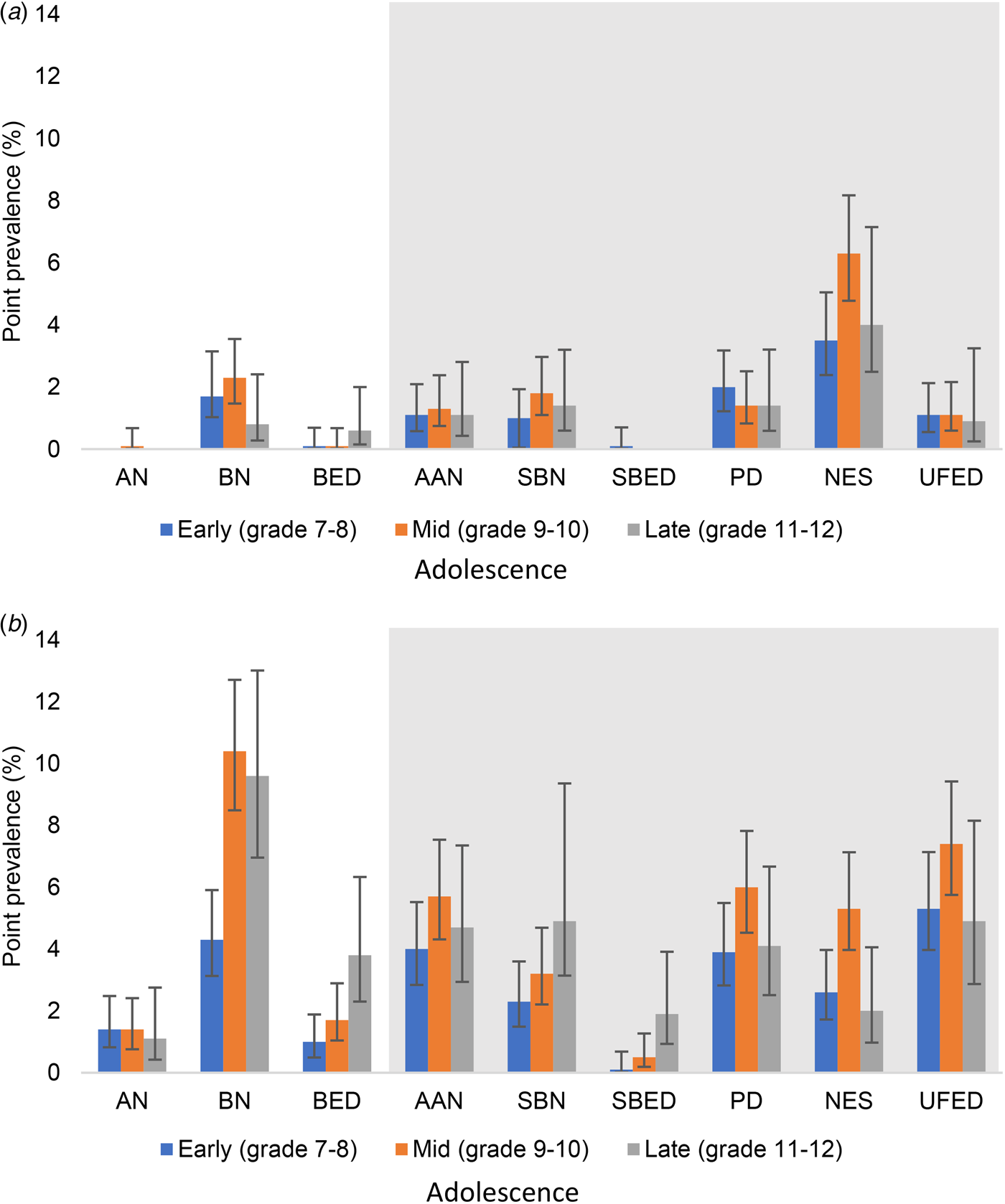

The point prevalence of each eating disorder is presented in Table 2 by gender, and broken down by gender and age group in Fig. 1. As can be seen, almost all eating disorders were more common in females or participants who identified their gender as other, except for NES.

Fig. 1. Point prevalence of DSM-5 eating disorders in adolescent (a) boys and (b) girls. Shaded area indicates other specified and unspecified feeding and eating disorders. AN, anorexia nervosa; BN, probable bulimia nervosa; BED, probable binge eating disorder; AAN, atypical anorexia nervosa; SBN, subthreshold bulimia nervosa; SBED, subthreshold binge eating disorder; PD, purging disorder; NES, night eating syndrome; UFED, unspecified feeding or eating disorder.

Table 2. Point prevalence of eating disorders and OSFED syndromes by gender and with/without a criterion for clinical significance

Lenient = K-10 >15 and/or PedsQL Physical or Psychosocial scale score <1s.d. below the sample mean. Stringent = K-10 ⩾30 and/or PedsQL Physical or Psychosocial scale score <1s.d. below the sample mean. †Diagnosis of NES and unspecified feeding or eating disorder includes the lenient criterion for clinical significance. All effects of gender were significant (p < 0.001 for all diagnoses except OSFED-BED where p = 0.014 and OSFED-NES where p = 0.020). Based on weighted data. Superscript ‘a’ and ‘b’ indicate statistically significant differences in prevalence estimates between gender groups. Total N for prevalence analyses varied for each diagnosis, dependent on the missingness of diagnostic data (AN: N = 4534; BN: N = 4508; BED/SBN/SBED/PD: N = 4505; AAN: N = 4494; NES: N = 4320; UFED: N = 4079; Major ED: N = 4509; OSFED: N = 4330; Any ED: N = 4136). Italicised text indicates estimates for merged diagnostic categories.

BMI correlates

As can be seen in Table 3, eating disorders on the whole were more likely to be experienced by adolescents who had a BMI percentile within the overweight or obese range. In particular, adolescents who met criteria for probable BN, probable BED, AAN, SBN, or UFED had significantly greater odds of being categorized as obese compared to adolescents without these disorders.

Table 3. Adjusted odds ratios for underweight, overweight and obesity relative to healthy weight in adolescents with eating disorders

Significant effects indicated in bold text. AOR, adjusted odds ratio; AN, anorexia nervosa; BN, probable bulimia nervosa; BED, probable binge eating disorder; AAN, atypical anorexia nervosa; SBN, subthreshold bulimia nervosa; SBED, subthreshold binge eating disorder; PD, purging disorder; NES, night eating syndrome; UFED, unspecified feeding or eating disorder.

All AORs are adjusted for gender, school grade and migrant status. Weight definitions are from the Center for Disease Control: <5th % = underweight, 5 to <85th % = healthy weight, 85th to <95th % = overweight, ⩾95% percentile = obese.

a No cases of underweight.

b No cases of overweight or obese. Based on weighted data (findings unchanged with un-weighted data).

Demographic correlates

Holding other demographic variables constant, participants in mid (grades 9–10) and late (grades 11–12) adolescence were equally likely as participants in early (grades 7–8) adolescence to meet criteria for AN, AAN, SBN, PD and UFED. Participants in both mid [OR 2.1, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.5–3.0] and late (OR 1.6, 95% CI 1.1–2.5) adolescence were however significantly more likely to meet criteria for probable BN, and participants in late adolescence were also much more likely to meet criteria for probable BED (OR 3.7, 95% CI 1.6–8.4) and subthreshold BED (OR 7.6, 95% CI 1.6–36.9) than early adolescents. Finally, participants in mid-adolescence but not late adolescence, were more likely than younger adolescents to meet criteria for NES (OR 2.0, 95% CI 1.4–2.8).

No effects of migrant or socioeconomic status were found on the likelihood of meeting criteria for any current eating disorders when controlling for age, gender and BMI percentile.

Criterion for clinical significance-adjusted prevalence estimates

As seen in Table 2, the prevalence of eating disorders when a lenient criterion for clinical significance was applied was reduced by only 1.5% (to 20.7%). However, applying the more stringent criterion reduced eating disorder prevalence by 8.6% (to 13.6%). Within diagnostic groups, adding this stringent criterion for clinical significance reduced prevalence by between 17.1% and 57.7%, with the greatest reductions observed in PD and UFED. Prevalence estimates that remained most robust to the addition of a criterion for clinical significance were probable BED, AN and AAN. Around 75% or more of the cases diagnosed with these disorders using DSM-5 diagnostic criteria met criteria for clinical significance.

Discussion

We found eating disorders to be common, with just over one in five adolescents (22.2%) meeting criteria for any DSM-5 diagnosis. We also found that applying a lenient criterion for clinical significance that allowed for participants who met symptomatic criteria to experience moderate distress and/or functional impairment had a negligible impact on prevalence. On the other hand, the application of a more stringent criterion, which captured participants who experienced severe distress and/or functional impairment, reduced eating disorder prevalence by two fifths to 13.6%. Until now, no study has examined all OSFED and UFED disorders in one sample of adolescents. Our findings align with similar research with adults (Hay et al., Reference Hay, Mitchison, Collado, González-Chica, Stocks and Touyz2017), demonstrating that these residual disorders (16.4%) are (around 2.5 times) more common than criterial eating disorders. The most common disorders were probable BN (4.6%), NES (4.1%), UFED (3.8%) and PD (3.2%). The least prevalent were subthreshold BED (0.3%), AN (0.7%) and probable BED (1.0%).

Our prevalence estimates were similar to previous adolescent studies (Allen et al., Reference Allen, Byrne, Oddy and Crosby2013; Micali et al., Reference Micali, Solmi, Horton, Crosby, Eddy, Calzo, Sonneville, Swanson and Field2015; Hammerle et al., Reference Hammerle, Huss, Ernst and Bürger2016), with a few exceptions. Our global prevalence of 22.2% is almost identical to the 21% reported by Hammerle and colleagues for early adolescents (Hammerle et al., Reference Hammerle, Huss, Ernst and Bürger2016), and sits between the prevalence estimates of 19 and 37% reported by Micali and colleagues for 14 and 16 year-olds, respectively (Micali et al., Reference Micali, Solmi, Horton, Crosby, Eddy, Calzo, Sonneville, Swanson and Field2015). PD was more common in our study; however, a post-hoc analysis suggests this may be explained by our inclusion of detox as a purging behavior. When this behavior was removed, the prevalence of PD reduced by almost two-thirds to 1.2%. Further, when detox was included, fewer than half of the PD cases were identified as clinically significant using the stringent definition. More research is required to determine whether using cleanses and detoxes for weight loss should be classified as a purging behavior, and how best to operationalize this. BN variants were high in prevalence. Their relatively higher rate compared to BED conforms to the known younger age of onset for BN (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Berglund, Chiu, Deitz, Hudson, Shahly, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Alonso, Angermeyer and Benjet2013). Despite high prevalence rates of BED in some population studies (Hudson et al., Reference Hudson, Hiripi, Pope and Kessler2007), the low prevalence observed in our study is on par with research using the full DSM-5 criteria for this disorder (Hay et al., Reference Hay, Mitchison, Collado, González-Chica, Stocks and Touyz2017; Udo and Grilo, Reference Udo and Grilo2018). In particular, the current study applied the criterion of binge eating-related distress, which has not always been included in previous studies, and found that doing so reduced the prevalence of probable BED by two thirds (data not presented). The inclusion of the distress criterion thus may address concerns about the over-pathologizing of binge eating (Frances and Widiger, Reference Frances and Widiger2012), which while being a common behavior, does not always confer distress (Mitchison et al., Reference Mitchison, Touyz, González-Chica, Stocks and Hay2017). OSFED syndromes were much more common than UFED, supporting the clinical utility of ‘other specified’ DSM-5 entities to reduce the rate of unspecified diagnosis. On the other hand, UFED was identified in almost 4% of adolescents, and in this study (unlike most previous studies) required evidence of distress and or impairment, which supports previous findings that UFED may be similarly impairing to full-syndrome eating disorders (Wade and O'Shea, Reference Wade and O'shea2015). Finally, while most previous studies (e.g. Allen et al., Reference Allen, Byrne, Oddy and Crosby2013; Hammerle et al., Reference Hammerle, Huss, Ernst and Bürger2016) have applied the 10th BMI percentile cut-off for AN used in the current study, others have applied different cut-offs. This inconsistency has implications for comparison of prevalence estimates across studies, especially the ratio of AN to BN/AAN. Although there is no definitive cut-off stipulated in the DSM-5, the clinical utility of a lower cut-off has recently been criticized (Andersen et al., Reference Andersen, Lindgreen, Rokkedal and Clausen2018).

All eating disorders except NES were more likely to be found among adolescents who identified their gender as female or other, in line with previous studies findings with these gender groups (Allen et al., Reference Allen, Byrne, Oddy and Crosby2013; Diemer et al., Reference Diemer, Grant, Munn-Chernoff, Patterson and Duncan2015). Yet eating disorders were also detected among 12.8% of boys, which highlights the need to include males in epidemiological studies. Our findings that eating disorders were similarly prevalent across age might reflect a lowering in the average age of onset since mid-late adolescence has typically been thought to be the peak age of onset (Schmidt et al., Reference Schmidt, Adan, Böhm, Campbell, Dingemans, Ehrlich, Elzakkers, Favaro, Giel, Harrison, Himmerich, Hoek, Herpertz-Dahlmann, Kas, Seitz, Smeets, Sternheim, Tenconi, Van Elburg, Van Furth and Zipfel2016; Volpe et al., Reference Volpe, Tortorella, Manchia, Monteleone, Albert and Monteleone2016). A 13-year-old in our study was as likely to meet criteria for AN as an 18-year-old. Probable BN and BED were exceptions, being more likely to be experienced in older adolescents. There was no effect of socioeconomic status or migrant status, confirming that eating disorders do not discriminate on the basis of wealth or origin (Mitchison et al., Reference Mitchison, Hay, Slewa-Younan and Mond2014; Mulders-Jones et al., Reference Mulders-Jones, Mitchison, Girosi and Hay2017).

Similar to recent prevalence studies in adults (Hay et al., Reference Hay, Mitchison, Collado, González-Chica, Stocks and Touyz2017), most adolescents with eating disorders had a greater than two-fold increased likelihood to fall within the obese weight range. As expected, this included eating disorders characterized predominantly by binge eating (e.g. probable BN and BED), but perhaps unexpectedly also included eating disorders characterized by extreme weight control behaviors (e.g. AAN and PD). This latter finding may reflect either the greater preponderance of eating disorder symptoms among those in the population at a higher weight (da Luz et al., Reference Da Luz, Sainsbury, Mannan, Touyz, Mitchison and Hay2017) or the role of unsupervised and maladaptive weight control practices in maintaining binge eating and/or high weight (Fairburn et al., Reference Fairburn, Cooper and Shafran2003). Longitudinal data is required to pin down these mechanisms.

This study provides the first population-based distribution data for NES; well overdue, considering this syndrome was first described by Stunkard in 1955 (Stunkard et al., Reference Stunkard, Grace and Wolff1955). We found NES to be very common, and the most common eating disorder among boys. These findings were similar to a study of undergraduates (Runfola et al., Reference Runfola, Allison, Hardy, Lock and Peebles2014). Contrary to original conceptions (Stunkard et al., Reference Stunkard, Grace and Wolff1955), it was also one of the few disorders not associated with obesity, which may be explained by the small quantity of food typically consumed during night eating episodes (Nolan and Geliebter, Reference Nolan and Geliebter2012). Further, distress and impairment were included in the operationalization of this syndrome in this study. These preliminary findings suggest that, rather than being trivial, confined to women (Striegel-Moore et al., Reference Striegel-Moore, Dohm, Hook, Schreiber, Crawford and Daniels2005) or people in larger bodies (Gallant et al., Reference Gallant, Lundgren and Drapeau2012b), NES among adolescents may be both common and disabling and worthy of further investigation.

Eating disorders are one of the rare cases in the DSM-5 that do not systematically include the clinical significance criterion (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). While there is contention regarding the incorporation of disability into definitions of disorder (Spitzer, Reference Spitzer1998), a core purpose of the clinical significance criterion is to reduce the potential for overdiagnosis in epidemiological studies (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Frances, Reference Frances2013). The current findings, tempered by the self-report nature of the design, suggests that the frequency of clinically significant eating disorders are less prevalent than current ‘raw’ estimates would suggest. This further implies, that in the broader community, the mere meeting of symptomatic criteria for an eating disorder is not uniformly associated with distress and/or impairment. Exceptions to this include full criterial AN and AAN, which were robust to the addition of the clinical significance criteria. It may be argued that the egosyntonicity of some eating disorder symptoms masks distress and impairment (Jenkins et al., Reference Jenkins, Hoste, Meyer and Blissett2011), making the addition of a clinical significance criterion spurious. Yet our findings regarding AN, considered the most ego-syntonic of the eating disorders, suggests that distress and impairment are self-identifiable by individuals with this disorder. Nonetheless, total prevalence of 13.6% for the full spectrum of ‘clinically significant’ eating disorders is demonstrative of a very high level of population health burden, affecting 1 in 7 youth.

Implications

The high rates of ‘raw’ eating disorder prevalence raises questions about overdiagnosis in epidemiological studies of eating disorders. In part, the utility of psychiatric diagnostic criteria is predicated on their ability to accurately identify psychiatric presentations which render clinically significant impairment or distress and thus require intervention. Future research in collaboration with the DSM and ICD Task Forces should consider the merit of including clinical significance as an additional criterion to the eating disorder diagnoses. This may have more impact on epidemiological rather than clinical practice, as it is well-documented that higher levels of distress and impairment are predictive of treatment-seeking among people with eating disorders (e.g. Mond et al., Reference Mond, Hay, Darby, Paxton, Quirk, Buttner, Owen and Rodgers2009). Another course of action might be to sharpen screening procedures to focus on identifying individuals with eating disorder symptoms that are associated with significant distress and/or impairment, as this will serve those in greatest need. Additionally, our findings relating to the greater preponderance of OSFED as opposed to criterial eating disorder presentations suggest that enhanced awareness of the subtleties of these presentations among primary care providers may be crucial.

It should also be noted that spontaneous recovery is not uncommon during adolescence (Patton et al., Reference Patton, Coffey, Carlin, Sanci and Sawyer2008), which is a time where self-regulation skills are still being developed – and in the context of increasing autonomy. Thus while uptake of weight control behaviors as well as difficulties in regulating overeating in our sample was high, it is also possible that for many adolescents these behaviors will manifest only transiently, self-correcting with time. This further underscores the need to parse out clinically significant presentations. A longitudinal study that examines whether distress/impairment during adolescence is a predictor of eating disorder trajectories, in terms of duration and severity, will be valuable and would further support the sharpening of screening procedures to capture ‘clinical significance’.

Limitations and strengths

Several limitations should be noted. First, diagnoses were defined using self-report measures, which may have impacted prevalence estimates. Previous studies have shown that participants report a higher frequency of behaviors on the EDE-Q compared to interview (Fairburn and Beglin, Reference Fairburn and Beglin1994), which may reflect either over-reporting or greater honesty when completing questionnaires. In order to clarify the accuracy of the current estimates, replication (preferably with a two-phase design - screening followed by an interview) is necessary. Second, symptoms over the past 1 month were assessed to reduce the timeframe over which adolescents were expected to recall. This preluded the inclusion of duration criteria in the diagnostic assignment of BN and BED, which require three months duration of behaviors. On the other hand, at least one study has demonstrated very little impact of a 1-month v. 3-month duration of binge eating on the prevalence of BED (Trace et al., Reference Trace, Thornton, Root, Mazzeo, Lichtenstein, Pedersen and Bulik2012). Third, distress and impairment were measured using generic rather than disease-specific instruments, and scores on these measures may have been influenced by comorbid psychiatric conditions not controlled for in this study. Thus while we were able to select out participants with an eating disorder who were not distressed/impaired, doubt remains over whether the distress/impairment in the remaining cases was due to the eating disorder or other comorbidities. Although the parceling out of impairment according to various comorbidities may be fraught (Mitchison et al., Reference Mitchison, Hay, Engel, Crosby, Le Grange, Lacey, Mond, Slewa-Younan and Touyz2013), it is recommended that future studies account for the presence of comorbid psychopathology. Fourth, this study does not include avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder, which is emerging as an associated feeding disorder of interest (Eddy et al., Reference Eddy, Thomas, Hastings, Edkins, Lamont, Nevins, Patterson, Murray, Bryant-Waugh and Becker2015), and which requires future epidemiological investigation. Strengths of this study were the large representative sample and high response rate for this population, as well as the measurement of a broad range of symptoms.

Conclusion

In the absence of a consistently applied clinical significance criterion, DSM-5 eating disorders are very common among adolescents, OSFED disorders particularly so. Most eating disorders are associated with being at a higher weight, which may be associated, in time, with physical health impairment. Including a criterion for clinical significance in the diagnostic formulation of eating disorders may reduce potential overpathologizing of eating disorders, and should be considered in future iterations of classification schemes as well as in screening programs that inform the allocation of treatment resources.

Author ORCIDs

Deborah Mitchison, 0000-0002-6736-7937.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the participants and their families and schools for contributing their time to the EveryBODY Study.

Financial support

This work was supported by a Macquarie University Research Fellowship (DM) and a Society for Mental Health Research Early Career Researcher Project Grant (DM).

Conflict of interest

Dr Mitchison is supported by the National Medical and Health Research Council (GNT 1158276). Professor Hay receives/has received sessional fees and lecture fees from the Australian Medical Council, Therapeutic Guidelines publication, and New South Wales Institute of Psychiatry and royalties/honoraria from Hogrefe and Huber, McGraw Hill Education, and Blackwell Scientific Publications, Biomed Central and PlosMedicine and she has received research grants from the NHMRC and ARC. She is Chair of the National Eating Disorders Collaboration Steering Committee in Australia (2019-) and Member of the ICD-11 Working Group for Eating Disorders (2012-) and was Chair Clinical Practice Guidelines Project Working Group (Eating Disorders) of RANZCP (2012–2015). She has conducted education for psychiatrists and prepared a report under contract for Shire Pharmaceuticals in regards to Binge Eating Disorder (July 2017). All views in this paper are her own.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.