Neuroticism is defined as the tendency to respond to various sources of stress with intense negative emotions (Barlow, Reference Barlow2002; Barlow, Ellard, Sauer-Zavala, Bullis, & Carl, Reference Barlow, Ellard, Sauer-Zavala, Bullis and Carl2014a, Barlow, Sauer-Zavala, Carl, Bullis, & Ellard, Reference Barlow, Sauer-Zavala, Carl, Bullis and Ellard2014b; Eysenck, Reference Eysenck1947; Goldberg, Reference Goldberg1993). The emotional experiences included within the neurotic spectrum include a range of negative effects (e.g. fear, irritability, anger, and sadness), with the greatest attention paid to anxious and depressive mood states. There is ample evidence to suggest that neuroticism is strongly associated with the onset of a number of mental and physical health conditions. Moreover, neuroticism is associated with other problematic outcomes (e.g. higher divorce rates, lost productivity, increased treatment seeking; Brickman, Yount, Blaney, Rothberg, & De-Nour, Reference Brickman, Yount, Blaney, Rothberg and De-Nour1996; Clark, Watson, & Mineka, Reference Clark, Watson and Mineka1994; Khan, Jacobson, Gardner, Prescott, & Kendler, Reference Khan, Jacobson, Gardner, Prescott and Kendler2005; Krueger & Markon, Reference Krueger and Markon2006; Lahey, Reference Lahey2009; Sher & Trull, Reference Sher and Trull1994; Smith & MacKenzie, Reference Smith and MacKenzie2006; Suls & Bunde, Reference Suls and Bunde2005; Weinstock & Whisman, Reference Weinstock and Whisman2006) over and above what can be explained by specific symptoms or formal psychiatric diagnoses. Given the public health significance of neuroticism, it is critical that we understand how best to alter it.

Malleability of neuroticism

Discrete conditions, such as the range of anxiety and depressive disorders, have long been the focus of intervention, rather than neuroticism, which has traditionally been considered more stable and inflexible (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). There is, however, increasing evidence that neuroticism may also change over time and in response to treatment. Several naturalistic, population-based studies suggest that neuroticism gradually decreases across the lifespan (Eaton, Krueger, & Oltmanns, Reference Eaton, Krueger and Oltmanns2011; Roberts & Mroczek, Reference Roberts and Mroczek2008; Roberts, Walton, & Viechtbauer, Reference Roberts, Walton and Viechtbauer2006) and may be influenced by life events (e.g. Roberts & Mroczek, Reference Roberts and Mroczek2008; Shiner, Allen, & Masten, Reference Shiner, Allen and Masten2017; Specht, Egloff, & Schmukle, Reference Specht, Egloff and Schmukle2011; Sutin, Costa, Wethington, & Eaton, Reference Sutin, Costa, Wethington and Eaton2010), though there appears to be great variability across individuals (Helson, Jones, & Kwan, Reference Helson, Jones and Kwan2002; Mroczek & Spiro, Reference Mroczek and Spiro2003; Small, Hertzog, Hultsch, & Dixon, Reference Small, Hertzog, Hultsch and Dixon2003).

In addition to naturalistic fluctuations, neuroticism may also change as a direct result of psychiatric treatments. A recent meta-analysis observed moderate between group effects comparing various forms of active treatment, including cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), to a no treatment control (Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Luo, Briley, Chow, Su and Hill2017). The authors of that study contend that greater change in neuroticism in the treatment group suggests the presence of intervention specific effects not attributable to changes in generalized distress or specific symptoms that are apt to fluctuate naturalistically in the control group (Clark, Vittengl, Kraft, & Jarrett, Reference Clark, Vittengl, Kraft and Jarrett2003; Jylhä & Isometsä, Reference Jylhä and Isometsä2006; Widiger, Verheul, & van den Brink, Reference Widiger, Verheul and van den Brink1999a, Reference Widiger, Verheul, van den Brink, Pervin and John1999b). But, the extent to which that is true depends on the degree of similarity between active and control treatments in altering symptomatic distress, and meta-analytic methods generally preclude the use of statistical techniques (e.g. Curran and Bauer, Reference Curran and Bauer2011; Fournier et al., Reference Fournier, Wright, Tackett, Uliaszek, Pilkonis, Manuck and Bagby2019) to directly control for the role of symptoms when measuring change in neuroticism over time.

Additionally, whereas a meta-analysis can provide information about the average effect of a certain type of treatment (e.g. CBT), these methods ignore potentially important differences across studies. For example, when change in neuroticism has also been examined in the context of cognitive-behavioral interventions, results have been quite mixed. For example, some authors have found significant decreases in neuroticism following a course of CBT (e.g. Kring, Persons, and Thomas, Reference Kring, Persons and Thomas2007), whereas others have not observed such improvements (Davenport, Bore, & Campbell, Reference Davenport, Bore and Campbell2010). In a large randomized-controlled trial (Tang et al., Reference Tang, DeRubeis, Hollon, Amsterdam, Shelton and Schalet2009), compared the effects of cognitive therapy (CT), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and placebo on neuroticism in adults with major depressive disorder. Both CT and SSRIs resulted in significantly larger improvements in neuroticism than placebo, an effect that remained after controlling for changes in depressive symptoms for individuals in the SSRI condition, but not for those receiving CT. In contrast, the advantage of SSRIs over placebo on improvement for depressive symptoms was not maintained after controlling for neuroticism. These results suggest that SSRIs produce a specific effect on neuroticism and indicate that temperament and psychopathology can change independently. Additionally, they suggest that whereas depressive symptoms are responsive to placebo, neuroticism is not. Thus, one potential reason for the mixed literature with regard to whether cognitive-behavioral interventions reduce neuroticism is that all of the studies reviewed above featured treatments that were originally designed to target disorder-specific symptoms, rather than neuroticism itself. This raises the possibility that effective treatments for neuroticism may need to be tailored to more directly target this dimension.

Treatment of neuroticism

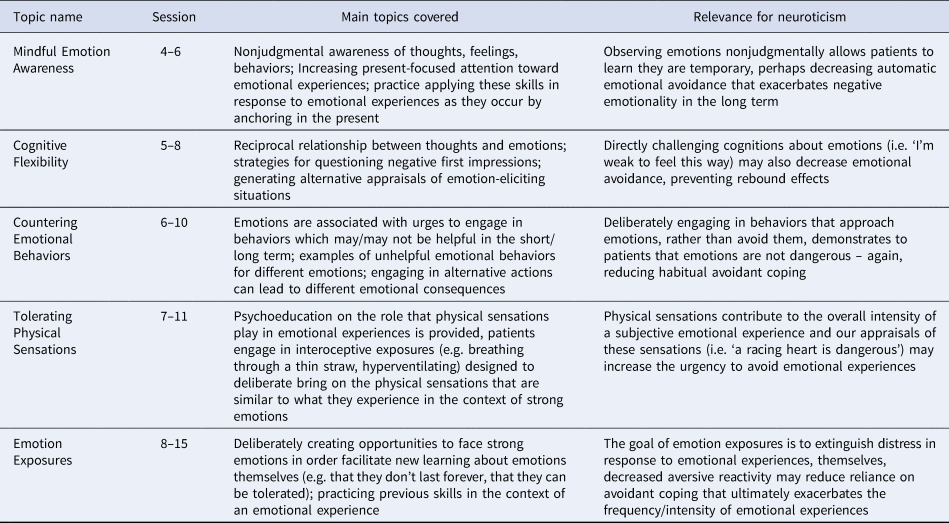

The Unified Protocol (UP) for Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders (Barlow et al. Reference Barlow, Farchione, Sauer-Zavala, Murray Latin, Ellard, Bullis and Cassiello-Robbins2018a, Reference Barlow, Sauer-Zavala, Farchione, Murray Latin, Ellard, Bullis and Cassiello-Robbins2018b) is a recently developed intervention with particular relevance for addressing neuroticism. The UP consists of several core treatment modules, described elsewhere (Payne, Ellard, Farchione, Fairholme, & Barlow, Reference Payne, Ellard, Farchione, Fairholme and Barlow2014) and summarized in Table 1, broadly aimed at extinguishing distress in response to the experience of strong emotions. By targeting aversive reactions to a wide variety of negative emotions when they occur, the UP may reduce reliance on the avoidant emotion regulation strategies that, paradoxically, have been shown to lead to more frequent and intense emotional experiences (Rassin, Muris, Schmidt, & Merckelbach, Reference Rassin, Muris, Schmidt and Merckelbach2000; Wegner, Schneider, Carter, & White, Reference Wegner, Schneider, Carter and White1987). Indeed, when negative emotions become less frequent over time, and when these changes are sustained, this may constitute decreases in neuroticism (for a description of what constitutes trait change, see Magidson, Roberts, Collado-Rodriguez, and Lejuez, Reference Magidson, Roberts, Collado-Rodriguez and Lejuez2014). The UP approach has shown efficacy in reducing symptoms for a range of anxiety and unipolar depressive disorders (Barlow et al., Reference Barlow, Farchione, Bullis, Gallagher, Murray-Latin, Sauer-Zavala and Cassiello-Robbins2017; Boswell, Anderson, & Barlow, Reference Boswell, Anderson and Barlow2014; Ellard, Fairholme, Boisseau, Farchione, & Barlow, Reference Ellard, Fairholme, Boisseau, Farchione and Barlow2010; Farchione et al., Reference Farchione, Fairholme, Ellard, Boisseau, Thompson-Hollands, Carl and Barlow2012), and there is data to suggest that it exerts small to moderate effects on measures of neuroticism compared with a waitlist (WL) condition (Carl, Gallagher, Sauer-Zavala, Bentley, & Barlow, Reference Carl, Gallagher, Sauer-Zavala, Bentley and Barlow2014).

Table 1. UP core modules

Note: The label ‘core modules’ refers to skills included in the UP that are purported to decrease aversive/avoidant reactions to emotional experience. In addition to the five core modules listed here, the UP also includes an introductory session on the nature of emotional disorders/overview of treatment (session 1), a motivational enhancement/goal setting module (session 2), and a psychoeducation module on the adaptive nature of emotions (sessions 3–4), and a relapse prevention module (session 12 for patients with panic disorder and session 16 for patients with all other principal diagnoses). Given that the UP is delivered flexibly at the discretion of patients and clinicians, the core modules were delivered across 1–2 sessions, with the exception of emotion emotions exposures that occurred for at least 4 sessions. Thus, we are unable to definitively link modules to sessions, though we can generally determine when patients were likely to receive specific content.

It is important to note that the UP is a cognitive behavioral intervention and, as described above, the literature is mixed with regard to whether CBT exerts an effect on neuroticism. In contrast to more traditional CBT approaches that focus on coping with discrete symptom constellations, the UP may be more adept at targeting neuroticism by addressing aversive/avoidant reactions to a broader range of strong emotions. For example, gold-standard cognitive-behavioral approaches for panic disorder are aimed at extinguishing anxiety associated with physiological sensations during a panic episode, over time leading to a reduction of the physiological sensations themselves. The UP is also designed to lead to these improvements, but in addition, may help the patient to tolerate a wider range of negative emotions that arise across a variety of life circumstances. This broad potential to change patients' relationship with their emotional experiences may allow for significant reductions in neuroticism. By contrast, standard disorder-focused CBT protocols, while efficacious for disorder symptoms, may not target a wide enough range of emotions to lead to robust changes in neuroticism.

Present study

The purpose of the present study is to add to the growing literature exploring the responsiveness of neuroticism to cognitive behavioral treatment generally, as well as to a transdiagnostic CBT protocol designed to target the broad array of negative emotional responses that characterize neuroticism. The present study utilized data from a large randomized-controlled trial comparing the UP to empirically supported single-diagnosis CBT protocols (SDPs), along with a WL control group, for diverse principal anxiety disorders and comorbid conditions (Barlow et al., Reference Barlow, Farchione, Bullis, Gallagher, Murray-Latin, Sauer-Zavala and Cassiello-Robbins2017). First, with our large sample, we sought to replicate preliminary findings (see Carl et al., Reference Carl, Gallagher, Sauer-Zavala, Bentley and Barlow2014) suggesting that the UP leads to significantly greater reductions in neuroticism compared to a WL control group. Additionally, we sought to explore the notion that changes in temperament, specifically neuroticism, are more robust when they are directly targeted in treatment. As a strict test of this hypothesis, we compared change in neuroticism as a function of active treatment condition and hypothesized that the UP would lead to greater changes in this dimension compared to disorder-specific, symptom-focused CBT protocols (SDP condition), all of which have established efficacy in treating symptoms. Given the evidence that some degree of change on measures of neuroticism reflects fluctuations in mood state, we examined change in neuroticism controlling for simultaneous changes in depression and anxiety symptoms.

Method

Participants

Participants in the present study were drawn from a large, intent-to-treat sample (N = 223) of treatment-seeking individuals who participated in a trial comparing two active treatment conditions and a WL control condition. The study was approved by a university institutional review board and written informed consent was obtained prior to any research activity. Individuals were eligible for the study if they were (1) 18 years or older; (2) fluent in English; and (3) assigned a principal (most interfering and severe) diagnosis of panic disorder, with or without agoraphobia (PD/A), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), or social anxiety disorder (SOC; see Table 2). Most patients met the criteria for at least one comorbid diagnosis [188 (84.3%)] and the mean (s.d.) number of comorbid diagnoses was 2.3 (1.8); there were no differences in clinical severity or prevalence of comorbid disorders as a function of study condition (Barlow et al., Reference Barlow, Farchione, Bullis, Gallagher, Murray-Latin, Sauer-Zavala and Cassiello-Robbins2017; Sauer-Zavala et al., Reference Sauer-Zavala, Bentley, Steele, Tirpak, Ametaj, Nauphal and Barlow2020; Steele et al., Reference Steele, Farchione, Cassiello-Robbins, Ametaj, Sbi, Sauer-Zavala and Barlow2018). Individuals taking psychotropic medications were required to have been stable on the same dose for at least 6 weeks prior to enrollment, and to maintain these medications and dosages throughout the treatment. Exclusion criteria consisted primarily of conditions that required immediate or simultaneous treatments that might interact with the study treatment in unknown ways (see Barlow et al., Reference Barlow, Farchione, Bullis, Gallagher, Murray-Latin, Sauer-Zavala and Cassiello-Robbins2017).

Table 2. Demographic and clinical characteristics

UP, unified protocol; SDP, single-diagnosis protocols; WL, waitlist.

Measures

Diagnostic

The Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule (ADIS; Brown & Barlow, Reference Brown and Barlow2014; Brown, Barlow, & DiNardo, Reference Brown, Barlow and DiNardo1994) is a semi-structured clinical interview that focuses on DSM diagnoses of anxiety, mood, somatic symptom, and substance use disorders, with screening questions for several additional disorders. Patients were assessed for current DSM diagnoses by individual evaluators who were blinded to condition allocation.

Neuroticism

The Eysenck Personality Questionnaire Revised-Short-Form (EPQR-S; Eysenck and Eysenck, Reference Eysenck and Eysenck1975) is a commonly used 48-item inventory consisting of the following subscales: Extraversion, Neuroticism, Psychoticism, and a Lie Scale. This scale has been shown to have good reliability and excellent validity (Brown, Reference Brown2007). The present study utilized the neuroticism subscale (12 items) and internal consistency at each assessment point was adequate (α ranged from 0.63 to 0.77). Example items include ‘are your feelings easily hurt’ and ‘would you call yourself a nervous person’ and respondents are prompted to select from either ‘yes’ or ‘no’.

Anxiety and depressive symptoms

The Hamilton Anxiety Ratings Scale (HARS; Hamilton, Reference Hamilton1959) and Hamilton Depression Ratings Scale (HDRS; Hamilton, Reference Hamilton1960) were used to provide clinician-rated assessment of anxiety and depressive symptoms, respectively. Both measures were administered in accordance with the Structured Interview Guide for the Hamilton Anxiety and Depression [SIGH-A (Shear et al., Reference Shear, Vander Bilt, Rucci, Endicott, Lydiard and Otto2001), SIGH-D (Williams, Reference Williams1988)]. These commonly used measures have demonstrated good levels of interrater and test–retest reliability, as well as convergent validity with similar clinician rated and self-report measures of psychiatric symptoms (Shear et al., Reference Shear, Vander Bilt, Rucci, Endicott, Lydiard and Otto2001). Independent clinical evaluators received extensive training on the SIGH-A and SIGH-D and had to demonstrate acceptable levels of reliability prior to their participation in the trial.

Procedure

A detailed description of the procedures, including randomization and participant flow, can be found in Barlow et al. (Reference Barlow, Farchione, Bullis, Gallagher, Murray-Latin, Sauer-Zavala and Cassiello-Robbins2017). In short, patients were randomized by their principal diagnosis (PD/A, GAD, OCD, or SOC), following a 2:2:1 allocation ratio, to UP, SDP, and WL control study conditions, respectively. After a baseline diagnostic assessment and randomization, patients in the UP and SDP conditions received between 12 and 16, 50–90 min (see below) weekly individual treatment sessions. They completed assessment batteries that included clinician-rated and self-report measures at baseline, following sessions 4, 8, and 12, and 16.

Treatment

The Unified Protocol (UP; Barlow et al. Reference Barlow, Farchione, Sauer-Zavala, Murray Latin, Ellard, Bullis and Cassiello-Robbins2018a, Reference Barlow, Sauer-Zavala, Farchione, Murray Latin, Ellard, Bullis and Cassiello-Robbins2018b) is a transdiagnostic cognitive-behavioral intervention designed to address the range of anxiety, depressive, and related disorders. The UP consists of eight treatment modules that are described in more detail elsewhere (e.g. Payne et al., Reference Payne, Ellard, Farchione, Fairholme and Barlow2014). Treatment session length of the UP was matched to the SDPs for each principal diagnosis (in accordance with the guidelines described below). The SDPs adopted in the present study included: Mastery of Anxiety and Panic – 4th edition (MAP-IV; Craske and Barlow, Reference Craske and Barlow2006); Treating Your OCD with Exposure and Response (Ritual) Prevention Therapy – 2nd edition (Foa, Yadin, & Lichner, Reference Foa, Yadin and Lichner2012); Mastery of Anxiety and Worry – 2nd edition (MAW-II; Zinbarg, Craske, and Barlow, Reference Zinbarg, Craske and Barlow2006); and Managing Social Anxiety: A Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Approach – 2nd edition (MSA-II; Hope, Heimberg, and Turk, Reference Hope, Heimberg and Turk2010). As recommended by the treatment developers, the OCD, MSA, and MAW protocols were conducted over the course of 16 sessions, whereas the MAP-IV was conducted over 12 sessions. All treatments were administered independently, with treatment sessions lasting for approximately 50–60 min. An exception was the OCD treatment protocols, which lasted 80–90 min for both UP and SDP conditions.

Waitlist

Individuals in the WL control condition were asked to complete study assessments during a 16-week period, without receipt of study interventions. Following completion of their WL participation, patients in this condition were offered 16 sessions of treatment with the UP.

Therapists and treatment integrity

Therapists for the study consisted of doctoral students in clinical psychology, postdoctoral fellows, and licensed psychologists. Initial training and certification in the treatment protocols followed the procedures that had been employed in clinical trials at our center over the last 30 years (Barlow, Gorman, Shear, & Woods, Reference Barlow, Gorman, Shear and Woods2000). The therapists were responsible for administering both UP and SDPs. Twenty percent of treatment sessions were randomly selected and sent to raters who were associated with the development of the specific treatments; these individuals rated study therapists for adherence and competence. Treatment fidelity scores were good to excellent (M, UP = 4.44 out of 5; SDPs = 4.09 out of 5).

Data analytic strategy

Our primary statistical analyses examined whether change in total neuroticism scores across the 16 weeks of active treatment differed among the treatment groups. Continuous data from the EPQ neuroticism scale were analyzed using multilevel models (MLMs, also known as hierarchical linear models or growth curve models) that adjusted for the repeated measures with nested random effects. Using this approach, each subject's symptom trajectory and EPQ neuroticism score at week-16 was estimated from a collection of patient-specific parameters. To optimally model the pattern of change over time, we examined linear, log-transformed, square-root transformed, and quadratic change trajectories. The best fitting model, determined by sample size adjusted Akaike information criterion (AICc), was the quadratic representation of time (AICc = 3594.1, for all other models, AICc > 3605.7). As such, we focus our primary hypotheses on model-estimated neuroticism scores at the intercept, centered to represent scores at week-16 or the end of treatment. Intercepts and instantaneous slopes were included as random effects, and an unstructured covariance matrix estimated the correlation among them. Because the inclusion of a random quadratic term did not significantly improve model fit (χ2(3) = 6.90, p = 0.08), it was modeled as a fixed effect. All independent variables, including terms representing the effect of treatment and the covariates, were entered simultaneously at the appropriate model level (Raudenbush and Byrk). Full maximum likelihood estimation was used, and the degrees of freedom were estimated with the Kenward–Roger approximation. All analyses were performed using SAS Version 9.4 Proc Mixed (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

To identify potential confounds to our primary hypotheses, we examined whether the treatment groups differed on clinical and demographic characteristics using a liberal p value (p < 0.10) to identify potentially important covariates. Likewise, we examined each clinical and demographic characteristic in separate MLMs (one model for each) to determine whether it was associated with the week-16 neuroticism scores, instantaneous slopes, or quadratic change trajectories at p < 0.10. Any variable on which the groups differed or any variable associated with any of these model parameters was included as a covariate in all of the models described below.

The test of our primary hypothesis was conducted in two steps. First, across all three groups, we examined differences in model-estimated neuroticism scores at week-16, controlling for the covariates identified using the procedures above. We included the WL control group in this analysis to provide an estimate of neuroticism change over time in the absence of treatment. Next, in order to examine whether any observed differences in neuroticism scores at week-16 remained after controlling for changes over time in anxiety and depression, we repeated the models above, adding measures of anxiety and depression as time varying covariates. In these models, we controlled for both mean levels of depression and anxiety over the acute phase of treatment, as well as assessment-to-assessment fluctuations in depression and anxiety levels over the treatment period (Curran & Bauer, Reference Curran and Bauer2011). Given the complexity of these latter models and given the smaller sample size in the WL condition, only the two active treatments, UP and SDP, were compared in this second step.

Results

Demographic and clinical measures

Table 2 displays demographic and clinical measures at baseline for the UP, SDP, and WL groups. The three groups differed with respect to the proportion of patients who were married, with the WL group containing the highest percentage, and in the proportion of participants who had received at least some college education, with the UP group containing the lowest percentage. The groups did not differ regarding any of the remaining variables at baseline.

Separate MLMs were used to screen the relationship between the baseline demographic and clinical variables and parameters representing change in neuroticism scores across treatment. Participant age was associated with instantaneous slopes at week-16 (F (1,665) = 4.38, p = 0.04) and with the quadratic term representing the curvature of the trajectory (F (1,538) = 4.62, p = 0.03); unemployment was associated with the quadratic term at the level of a non-significant trend (F (1,507) = 2.99, p = 0.08, see full model results in online Supplementary Table S1). As such, these four variables (marital status, education level, age, and unemployment) were included as covariates in models testing our primary hypotheses.

Change in neuroticism in the three treatment groups

Table 3 presents the parameters from the MLM of change in EPQ neuroticism scores over time and Fig. 1 displays the raw means at each assessment point for EPQ neuroticism, HARS, and HDRS, separately for each treatment. We observed no differences among the treatments at baseline on neuroticism (F (2,216) = 0.81, p = 0.45), HARS (F (2,220) = 0.02, p = 0.98), or HDRS (F (2,220) = 0.04, all p = 0.96). The primary statistic of interest in the MLM was the effect of treatment on estimated neuroticism scores at the week-16, controlling for the above covariates. We observed a significant main effect of treatment (F (2,213) = 3.57, p = 0.03, Table 3, Fig. 2) such that the UP group evidenced lower week-16 neuroticism scores than either the SDP [t (218) = −2.17, p = 0.03, d = −0.32, 95% confidence interval (CI) −0.62 to −0.03] or the WL (t (207) = −2.33, p = 0.02, d = −0.43, 95% CI −0.80 to −0.07) groups. We observed no difference in week-16 neuroticism scores between the SDP and WL groups (t (212) = −0.55, p = 0.58, d = −0.10, 95% CI −0.46 to 0.26).

Fig. 1. Raw mean (a) neuroticism, (b) anxiety, and (c) depression scores in each treatment at each assessment week.

Fig. 2. Estimated neuroticism scores at week-16. Error bars represent ±1 s.e. UP, unified protocol; SDP, single-disorder protocols; WL, waitlist. *p < 0.05.

Table 3. MLM of changes in neuroticism over 16 weeks

UP, unified protocol; SDP, single-disorder protocols; WL, waitlist.

Change in neuroticism in the two active treatment arms, controlling for symptoms

In a separate model, we examined differences in week-16 neuroticism scores between the UP and SDP conditions controlling for mean level and fluctuations in depression and anxiety over the trial. First, we observed a significant between-subjects effect of average depression on estimated neuroticism levels at week-16 such that individuals with higher mean levels of depression had higher post-treatment neuroticism scores (F (1,191) = 9.35, p = 0.003). We observed no effect of fluctuations in depression scores over the trial on neuroticism scores (F (1,487) = 0.78, p = 0.38). By contrast, we observed a significant association between fluctuations in anxiety levels and neuroticism scores whereby increased levels of anxiety, relative to an individual's mean, were associated with increases in neuroticism scores (F (1,516) = 50.47, p < 0.001). The effect of between-participant differences in mean anxiety on week-16 neuroticism scores was not significant (F (1,197) = 0.69, p = 0.41). Critically, the main effect of treatment on week-16 neuroticism remained significant when controlling for all of these effects and for the covariates identified above,Footnote †Footnote 1 such that week-16 neuroticism scores were lower in the UP than the SDP groups (F (1,176) = 7.72, p = 0.006, d = −0.42, 95% CI −0.71 to −0.12; full model results are presented in online Supplementary Table S2).Footnote 2

Discussion

The current study is the first of its kind to compare different, active behavioral treatments with respect to their effect on neuroticism. Results suggest that the UP, a transdiagnostic intervention designed to target the broad array of negative emotional reactions, was associated with significant reductions in this dimension in a treatment-seeking sample of individuals with heterogeneous anxiety disorders and comorbid conditions. Notably, patients in the UP condition evidenced lower levels of neuroticism at week-16 (post-treatment) than did those in the SDP and WL conditions. Further, no differences were seen between the SDP and WL conditions on neuroticism scores at week-16, indicating that gold-standard, symptom-focused approaches may not provide an advantage over no treatment (i.e. WL) in targeting this dimension, despite the advantage of these approaches over WL in targeting symptoms (Barlow et al., Reference Barlow, Farchione, Bullis, Gallagher, Murray-Latin, Sauer-Zavala and Cassiello-Robbins2017). Of note, the greatest divergence among UP and SDP treatments in the trajectories of change in neuroticism occurred during the final four sessions. At this point in the study, all patients were engaging in exposures, but the focus of these exercises differed across conditions. The goal of exposure in the SDPs is to extinguish distress in response to specific fear-eliciting situations (e.g. public speaking and contamination), whereas in the UP condition, the focus is on facilitating new learning about emotions themselves (e.g. emotions are temporary and tolerable) regardless of situation. The UP may reduce neuroticism to a greater extent due to its focus on exposure to a broad array of negative emotions across situations, as opposed to the situation specific focus of SDPs. But, future research would be necessary to clarify the mechanisms underlying the unique effect of specific UP treatment components on neuroticism.

Additionally, despite significant symptom improvement observed across both active treatment conditions, fluctuations in depression and anxiety do not appear to account for changes in neuroticism in this sample. Specifically, we simultaneously controlled for average levels of depression and anxiety across treatment, as well fluctuations in these symptoms, and the UP condition continued to show significantly lower neuroticism scores at week-16 compared to the SDP condition. Together, these findings provide evidence that neuroticism may be most apt to change in treatment when it is directly targeted. Given that symptoms improved in both active treatment conditions, yet reductions in neuroticism were only observed for the UP condition, it is worth considering the clinical significance of a treatment that can address both acute disorder symptoms and temperamental vulnerabilities. Future research should explore whether change in neuroticism leads to functional improvements related a wide range emotional experience (i.e. tolerating anger in a romantic relationship), beyond the circumscribed emotional/situational impairments that abate in disorder-specific CBT in the short term. Additional work can examine whether reductions in neuroticism prevent the emergence of future emotional disorders that are also characterized by aversive, avoidant responses to strong emotions.

The current findings add to the existing body of literature aimed at addressing whether temperamental variables, such as neuroticism, are responsive to treatment efforts. First, consistent with Tang et al.'s (Reference Tang, DeRubeis, Hollon, Amsterdam, Shelton and Schalet2009) results, we found that neuroticism and psychopathology (i.e. depression and anxiety) are not isomorphic and can change independently. Additionally, though evidence of neuroticism's sensitivity to change in the context of previous treatment outcome trials has been mixed (Eaton et al., Reference Eaton, Krueger and Oltmanns2011; Kring et al., Reference Kring, Persons and Thomas2007; Tang et al., Reference Tang, DeRubeis, Hollon, Amsterdam, Shelton and Schalet2009), by comparing emotion-focused (UP) and traditional CBT (SDP) approaches, the present study suggests that more robust effects are demonstrated when neuroticism is targeted more directly. Moreover, the present study extends the meta-analytic work of Roberts et al. (Reference Roberts, Luo, Briley, Chow, Su and Hill2017). Our between condition effects comparing the UP to WLC were similar to Roberts' estimates exploring differences in the magnitude of neuroticism change between treatment in general (any orientation) and a no-treatment condition; however, the present study provides an even more stringent evaluation by explicitly controlling for fluctuations in depression and anxiety, along with directly comparing the UP to other effective CBT approaches. Regarding these comparisons, we observed an advantage of the UP over the other CBT approaches for the reduction of neuroticism that is similar to the effect-size differences reported between active medications and placebo in the treatment of depressive symptoms (Turner et al., 2008). Given that emerging dimensional models of psychopathology include additional broad domains, beyond neuroticism, that can account for the full range of mental disorders (e.g. Kotov et al., Reference Kotov, Krueger, Watson, Achenbach, Althoff, Bagby and Zimmerman2017), it is important for future research to explore whether additional personality dimensions are also amenable to change in response to targeted treatments.

Limitations of the current study warrant mention. First, the treatments evaluated in the current study were developed at our center (three of the four SDPs and the UP) and were delivered by providers with strong CBT training. This limitation may impact generalizability of study results to other locations and patient populations. Additionally, the majority of the work addressing neuroticism's responsiveness to treatment has been conducted in the context of major depressive disorder (Tang et al., Reference Tang, DeRubeis, Hollon, Amsterdam, Shelton and Schalet2009); the present sample consisted of individuals with principal anxiety disorders and, although a subset were also diagnosed with a comorbid depressive disorder, it is unclear whether results will generalize to individuals with primary depression (n = 31, see Sauer-Zavala et al., Reference Sauer-Zavala, Bentley, Steele, Tirpak, Ametaj, Nauphal and Barlow2020). Additionally, it would also be useful for future research to include more frequent assessment of neuroticism and symptom levels to elucidate the relative timing of changes in these features during treatment, along with larger samples and longer follow-up periods in which return to treatment was carefully controlled. These features would allow for the kinds of measurement models that can better disentangle state/trait effects over time (Fournier et al., Reference Fournier, Wright, Tackett, Uliaszek, Pilkonis, Manuck and Bagby2019), and they would allow for the determination of the relative durability of neuroticism changes with treatment.

Conclusions

Given that neuroticism is associated with a wide range of public health problems, interventions that target this dimension in treatment may have far reaching effects. The current study demonstrates that the UP has a specific effect on change in neuroticism relative to other active CBT treatments. These findings shed light on the mixed literature with regard to neuroticism's treatment responsiveness; by directly comparing neuroticism-focused CBT (i.e. UP) to more traditional approaches, results suggest that improvements in neuroticism are more robust when it is directly targeted in treatment.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720000975.

Financial support

This study was funded by grant R01 MH090053 from the National Institute of Mental Health awarded to Dr David H. Barlow.

Conflict of interest

Dr Barlow receives royalties from Oxford University Press (which includes royalties for all five treatment manuals included in this study), Guilford Publications Inc., Cengage Learning, and Pearson Publishing. Dr Fournier receives royalties from Guilford Publications Inc. There are no disclosures for the remaining authors.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.