Introduction

There is common concern over the use during pregnancy of antidepressant drugs, notably selective serotonin receptor inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors or selective noradrenergic reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs). Comparatively little has been published on the use of tri- or tetracyclic antidepressants (TCAs or TeCAs) and monoamine oxidase A inhibitors (MOAIs).

Many reviews have been published on pregnancy outcome after maternal use of antidepressants (e.g. Hines et al. Reference Hines, Adams, Buck, Faber, Holson, Jacobson, Keszler, McMartin, Segraves, Singer, Sipes and Williams2004; Einarson & Einarson, Reference Einarson and Einarson2005; Hallberg & Sjöblom, Reference Hallberg and Sjöblom2005; Källén, Reference Källén2007, Reference Källén, Hansson and Olsson2008). Exposure to antidepressants during pregnancy has been linked to various adverse outcomes. In most studies, first-trimester exposure to any antidepressant has not been associated with an increased risk for congenital malformations, but an association between paroxetine use and cardiac defects has been suggested by some authors (Diav-Citrin et al. Reference Diav-Citrin, Shechtman, Weinbaum, Arnon, Di Gianantonio, Clementi and Ornoy2005; Bar-Oz et al. Reference Bar-Oz, Einarson, Einarson, Boskovic, O'Brien, Malm, Berard and Koren2007; Bérard et al. Reference Bérard, Ramos, Rey, Blais, St-Andre and Oraichi2007; Cole et al. Reference Cole, Ephross, Cosmatos and Walker2007; Källén & Otterblad Olausson, Reference Källén2007) but not others (e.g. Davis et al. Reference Davis, Rubanowice, McPhillips, Raebel, Andrade, Smith, Yood and Platt2007). A similar association with fluoxetine has also been found in some studies (Diav-Citrin et al. Reference Diav-Citrin, Shechtman, Weinbaum, Wajnberg, Avgil, Di Gianantonio, Clementi, Weber-Schoendorfer, Schaefer and Ornoy2008; Oberlander et al. Reference Oberlander, Warburton, Misri, Riggs, Aghajanian and Hertzman2008b) but not in others (e.g. Källén & Otterblad Olausson, Reference Källén2007). A recent study (Pedersen et al. Reference Lund, Pedersen and Henriksen2009) found an increased risk for septal defects after sertraline and citalopram but not after fluoxetine or paroxetine, but confidence intervals were large and based on only a few cases and the difference between drugs was uncertain. The finding may have been biased by the way that malformations were identified. Clomipramine has also been linked to an increased risk of cardiovascular defects (Källén & Otterblad Olausson, Reference Källén and Otterblad Olausson2003) but there is little evidence for an association with other antidepressants.

Other than the association with cardiovascular malformations, no clear evidence exists for an association with maternal antidepressant use. One study found a generally increased risk for congenital malformations after the use of SSRIs (Wogelius et al. Reference Wogelius, Norgaard, Gislum, Pedersen, Munk, Mortensen, Lipworth and Sorensen2006) but this finding may have been biased by the data source used (Källén, Reference Källén2007). In two retrospective case–control studies, tentative associations between maternal use of SSRIs and specific malformations (anencephaly, craniosynostosis and omphalocele) were suggested (Alwan et al. Reference Alwan, Reefhuis, Rasmussen, Olney and Friedman2007), observations that were not confirmed in a further study (Louik et al. Reference Louik, Lin, Werler, Hernandez-Diaz and Mitchell2007), where an association with clubfoot was seen.

Most authors agree that women using antidepressants have a tendency to preterm delivery (McElhatton et al. Reference McElhatton, Garbis, Elefant, Vial, Bellemin, Mastroiacovo, Arnon, Rodriguez-Pinilla, Schaefer, Pexieder, Merlob and Dal Verme1996; Ericson et al. Reference Ericson, Källén and Wiholm1999; Simon et al. Reference Simon, Cunningham and Davis2002; Malm et al. Reference Malm, Klaukka and Neuvonen2005; Suri et al. Reference Suri, Altshuler, Hellemann, Burt, Aquino and Mintz2007; Lund et al. Reference Lund, Pedersen and Henriksen2009). However, in some studies of preterm delivery in depressed women (Chung et al. Reference Chung, Lau, Yip, Chiu and Lee2001; Dayan et al. Reference Dayan, Creveuil, Herlicoviez, Herbel, Baranger, Savoye and Thouin2002, Reference Dayan, Creveuil, Marks, Conroy, Herlicoviez, Dreyfus and Tordjman2006; Orr et al. Reference Orr, James and Blackmore Prince2002), the possible confounding from antidepressant drug use was not always clarified. Li et al. (Reference Li, Liu and Odouli2009) studied a population of depressed women with a low use of antidepressants, and exclusion of women who used these drugs did not change the increased risk estimate. Wisner et al. (Reference Wisner, Sit, Hanusa, Moses-Kolko, Bogen, Hunker, Perel, Jones-Ivy, Bodnar and Singer2009), in a small study, found 20% preterm delivery rates at both continued SSRI exposure and continued untreated depression. In a large population-based linked health data study, lower birthweight was found in infants whose mothers had used SSRIs than in infants whose mothers had a similar degree of depression but were not treated with medication (Oberlander et al. Reference Oberlander, Warburton, Misri, Aghajanian and Hertzman2006). The same research group (Oberlander et al. Reference Oberlander, Warburton, Misri, Riggs, Aghajanian and Hertzman2008b) found that length of gestational SSRI exposure rather than timing increased the risk for low birthweight and reduced gestational age, even when controlling for maternal illness and medication dose.

Numerous studies have described neonatal symptoms associated with maternal use of antidepressants, notably SSRIs; for example, respiratory difficulties, low Apgar score, hypoglycaemia, jaundice, cyanosis at feeding, and cerebral excitation (Costei et al. Reference Costei, Kozer, Ho, Ito and Koren2002; Källén, Reference Källén2004; Sanz et al. Reference Sanz, De-las-Cuevas, Kiuru, Bate and Edwards2005; Oberlander et al. Reference Oberlander, Warburton, Misri, Aghajanian and Hertzman2006, Reference Oberlander, Warburton, Misri, Aghajanian and Hertzman2008a; Lund et al. Reference Lund, Pedersen and Henriksen2009). These diagnoses resulted in an increased rate of admissions to neonatal units. Again, some of these effects were also seen in infants of untreated depressed women. Such mild events may be common (Levinson-Castiel et al. Reference Levinson-Castiel, Merlob, Linder, Sirota and Klinger2006). Rare, severe neonatal complications have also been described. Persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN) was found to occur more often than expected after SSRI use (Chambers et al. Reference Chambers, Hernandez-Diaz, Van Marter, Werler, Louik, Jones and Mitchell2006; Källén & Otterblad Olausson, Reference Källén, Hansson and Olsson2008) but in other studies no such association was found, although the number of cases was low (Andrade et al. Reference Andrade, McPhillips, Loren, Raebel, Lane, Livingston, Boudreau, Smith, Davis, Willy and Platt2009; Wichman et al. Reference Wichman, Moore, Lang, St Sauver, Heise and Watson2009). One study suggested that antenatal use of SSRIs could prolong the QT interval in the newborn (Dubnov-Raz et al. Reference Dubnov-Raz, Juurlink, Fogelman, Merlob, Ito, Koren and Finkelstein2008). Case reports suggested an association between exposure to paroxetine (Stiskal et al. Reference Stiskal, Kulin, Koren, Ho and Ito2001), escitalopram (Potts et al. Reference Potts, Young, Carter and Shenai2007) or venlafaxine (Treichel et al. Reference Treichel, Schwendener Scholl, Kessler, Joeris and Nelle2009) and necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC).

In the current study we present data on different aspects of delivery outcome after maternal use of antidepressants. Data were obtained from Swedish national health registers with a prospective registration of drug use. This work expands the data shown in previous publications from this data base (Ericson et al. Reference Ericson, Källén and Wiholm1999; Källén & Otterblad Olausson, Reference Källén and Otterblad Olausson2003, Reference Källén and Otterblad Olausson2006, Reference Källén and Otterblad Olausson2007; Källén, Reference Källén2004). In addition to the main text tables, Appendices 1–9 are presented as Supplementary material (available online) to provide a deeper understanding of the reported data.

Method

The study is based on data from the Swedish Medical Birth Register (MBR; National Board of Health and Welfare, 2003) from 1 July 1995 up to 2007. This register contains information on almost all deliveries in Sweden (1–2% missing), with data collected during prenatal care (nearly every pregnant woman attends the free prenatal care system), delivery, and the paediatric examination of the newborn infant. Information on drug use is based partly on an interview conducted by the midwife at the first antenatal visit (in 90% of cases before the end of the first trimester, with the majority being between weeks 10 and 12) (‘early use’) and partly on information from the antenatal care with respect to drugs prescribed later during the pregnancy by the attending doctor (‘later use’). The drug names are transferred to Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) codes for data storage. Information on the exact timing and amount of drugs used is often incomplete. Information on intrauterine growth was obtained by using growth charts from the Swedish MBR (Källén, Reference Källén1995). The information used from the MBR is shown in Appendix 1 (available online).

With regard to studies of congenital malformations, data were also obtained from the Register of Birth Defects (previously known as the Register of Congenital Malformations) and the Patient Register (previous the Hospital Discharge Register). The various registers were linked with the aid of the personal identification number that is assigned to everyone living in Sweden and a common file was formed (National Board of Health and Welfare, 2004). Malformed infants were identified from ICD codes: ICD-9 codes 740–759 or later ICD-10 codes beginning with Q. First, the presence of any type of malformation, irrespective of severity, was noted. Then a restriction was made, excluding malformed infants who had one or more of the following conditions: pre-auricular appendix, tongue tie, patent ductus in a preterm infant, single umbilical artery, undescended testicle, hip (sub)luxation, and nevus. These conditions are common, variable in recording, and of lower clinical significance. The remaining infants were said to have ‘relatively severe malformations’, even though some mild conditions are still included in the group. Specific types of malformations were then analysed separately, each type irrespective of whether other malformations were present but with exclusion of infants with known chromosome anomalies.

From the MBR we identified all women who had reported the use of an antidepressant since she became pregnant (‘early use’) or had had such drugs prescribed by antenatal care (‘later use’). These women were compared with all other women in the register using Mantel–Haenszel analysis after adjustment for pertinent variables, always including year of delivery, maternal age, parity, smoking, and body mass index (BMI). Odds ratios (ORs) were calculated with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). When the expected number of outcomes was <10, risk ratios (RRs) were calculated instead, as observed numbers divided by expected numbers with 95% CI based on exact Poisson distributions (SABER software; CDC, USA).

Results

Overview of material

We identified 14 821 women who were exposed to antidepressants: 12 914 had early exposure, 5987 later exposure and 4080 had both. The total number of infants born was 15 017, 13 080 after early, 6066 after later, and 4127 after both early and later exposure. These were compared with 1 062 190 women with 1 236 053 infants in the population.

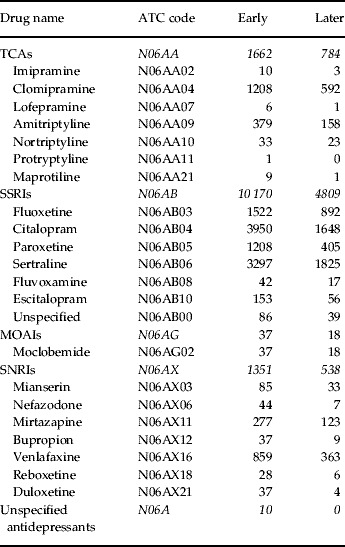

Table 1 lists the number of women according to antidepressant drug used, divided into four groups: TCAs, SSRIs, MOAIs, and other antidepressants, which we call SNRIs. There were also 10 women who did not specify the drug used and 86 early and 39 later who stated unspecified SSRIs. The table shows that, in the TCA group, clomipramine dominated. Among SSRIs, citalopram was the most common drug in early pregnancy followed by sertraline, fluoxetine and paroxetine. In later pregnancy, sertraline was used most often, followed by citalopram, fluoxetine and paroxetine. Other SSRIs were represented by only a few women. Among SNRIs, venlafaxine dominated, followed by mirtazapine both early and later.

Table 1. Number of women using specific antidepressant drugs either before the first antenatal visit (‘Early’) or prescribed the drugs during pregnancy (‘Later’)

TCA, Tricyclic antidepressant; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; SNRI, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; MOAI, monoamine oxidase A inhibitor; ATC, Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical.

A total of 311 women reported in early pregnancy the use of two or three drugs belonging to different groups and 162 women received combinations of two groups later in pregnancy (Appendix 2).

Maternal characteristics

Women using antidepressant are characterized by higher age and lower parity than other women, they are more often smokers and of high BMI. They are less often born outside Sweden, are more often non-cohabiting and work less often full-time outside the home. A comparison of some of the characteristics of women reporting antidepressant use in early pregnancy and all women who gave birth is given in Appendix 3.

These women also used other drugs in early pregnancy in a different pattern than other women. This may indicate co-morbidity (e.g. drugs for stomach ulcer and reflux, insulin, drugs for hypertension, systemic corticosteroids, tyroxine, anti-asthmatics) but the most important use of co-medication refers to other psycho-active drugs with a very high usage of sedatives and hypnotics but also neuroleptics, drugs for migraine, and anticonvulsants (Appendix 4).

Maternal delivery diagnoses

Pre-existing diabetes and chronic hypertension seem to be risk factors for any antidepressant drug use during pregnancy. Several other maternal diagnoses given at delivery were analysed (Table 2). Most of them occur in excess and in most the difference between the effect of early and later exposure is not very marked. Placental abruption seems to occur more often after early exposure than after later exposure but the difference may be random.

Table 2. Some maternal delivery diagnoses after use of antidepressants (ADs) early in pregnancy, later in pregnancy, and both early and later in pregnancy. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) after adjustment for year of birth, maternal age, parity, smoking and body mass index (BMI)

a Analysed only for deliveries that did not start with a caesarean section: 984 394 in the population, 11 407 after early use, 5233 after later use, and 3550 after both early and later use.

Infant characteristics: gestational duration and birthweight

Pregnancy duration and birthweight was analysed for singletons after maternal use of antidepressants either ‘early’, ‘later’ or ‘both early and later’. There is an excess of preterm births (<37 weeks) and a slight increase in low birthweight (<2500 g) but no increase in small for gestational age (SGA). On the contrary, large for gestational age (LGA) occurs in excess but with no great differences between outcomes after early or later exposures. However, for preterm birth and low birthweight there is a tendency of high ORs after later exposure and notably after both early and later exposure (Appendix 5).

To detect differences in gestational duration and birthweight after later exposure of either TCAs, SSRIs or SNRIs, the same characteristics as those described above were compared (Table 3). There is a tendency for a higher risk for preterm birth and low birthweight after TCA exposure than after SSRI. SNRI exposure is intermediate with respect to risk for preterm birth but shows a higher risk for low birthweight than SSRI and also shows a significant SGA effect, which is not seen for the other two groups.

Table 3. Effect of preterm birth and birthweight in singletons according to antidepressant (AD) use later in pregnancy. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence interval (CIs) adjusted for year of birth, maternal age, parity, smoking and body mass index (BMI)

SGA, Small for gestational age; LGA, large for gestational age; AD, antidepressant; TCA, tricyclic antidepressant; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; SNRI, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; s.d., standard deviation.

Infant characteristics: neonatal diagnoses

Seven neonatal conditions were selected for analysis, but PPHN could be studied only after the introduction in 1997 of ICD-10. In the Swedish version of the ICD-10 code list, a specific code has been given to PPHN (P293B). Table 4 summarizes data for the six other diagnoses after maternal use (‘early’, ‘later’ and ‘both early and later’) of any antidepressant. All conditions occur in excess and the risk estimates are higher after later exposure than after early exposure. For some conditions, the highest estimates were seen after exposure both early and later. However, none of the differences are very marked. The same six neonatal diagnoses were evaluated with regard to later exposure of TCA, SSRI or SNRI. The OR is significantly increased for hypoglycaemia, respiratory diagnoses and low Apgar score primarily after the use of TCAs but also of SNRIs and SSRIs. Additionally, an increased risk for jaundice was seen after the use of TCAs and SNRIs (Appendix 6).

Table 4. Six neonatal diagnoses in infants born after maternal antidepressant (AD) use. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) adjusted for year of birth, maternal age, parity, smoking and body mass index (BMI)

CNS, Central nervous system; AD, antidepressant.

The seventh neonatal diagnose analysed was PPHN after maternal use of SSRIs (no PPHN with other antidepressants). Analysis was restricted to infants with a gestational duration of at least 34 completed weeks; at shorter gestation the basic risk for PPHN is strongly increased. The figures are low for this rather unusual condition but a significantly increased risk is seen: RR for exposure in early pregnancy was 2.30 (95% CI 1.29–3.80), for later exposure 2.56 (95% CI 1.17–4.85), and for both early and later exposure 3.44 (95% CI 1.49–6.79). In the total Swedish population during 1997–2007 there were 1 019 514 infants born, and 572 cases of PPHN were diagnosed, a rate of 0.56 per 1000 (Appendix 7).

Infant characteristics: congenital malformations

The total rate of any congenital malformation in the population is 4.3% and in 2.9% there was at least one ‘relatively severe malformation’. Among the 25 groups of malformations, two showed a statistically significant excess (‘relatively severe malformations’ and ‘hypospadias’) after exposure to antidepressants. Appendix 8 presents the complete list on the presence of congenital malformations after maternal use of any antidepressants.

When the three main groups of antidepressants were studied separately, risk differences were seen (Table 5). The risks for a relatively severe malformation, for any cardiovascular defect, and for a ventricular (VSD) or atrial septal defect (ASD) were significantly increased only for TCAs (primarily clomipramine, see Table 1). The risk estimates for hypospadias was increased for all three groups but did not reach statistical significance. None of the women with a hypospadic infant reported the use of an anticonvulsant. The risk for cystic kidney was elevated for SSRI use but was based on only nine cases. Three of these cases were infantile polycystic kidney and one adult-type polycystic kidney, both usually regarded as genetic, one had an unspecified polycystic kidney, three had cystic dysplasia, and one had a fibrocystic kidney disease.

Table 5. Five groups of congenital malformations where risks seemed to differ with the group of antidepressant used. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence interval (CIs) adjusted for year of birth, maternal age, parity, smoking and body mass index (BMI)

TCA, Tricyclic antidepressant; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; SNRI, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; VSD, ventricular septal defect; ASD, atrial septal defect.

a Risk ratio (observed/expected number) with exact 95% CI based on Poisson distributions.

There was no significantly increased risk for abdominal wall defects after maternal use of antidepressants (Appendix 8). Among the seven abdominal wall defects recorded, four had gastroschisis. One was exposed to clomipramine, one to citalopram, and two to fluoxetine. The expected number of infants with gastroschisis is 1.77, with an RR of 2.26 (95% CI 0.62–5.79).

Most women who reported SSRI use had taken one of four specific drugs: fluoxetine, citalopram, paroxetine or sertraline. In Table 6 the malformation risks after use of each of these drugs are compared. There is a significantly increased risk for a relatively severe malformation after fluoxetine but a comparison of the rates between the drugs showed that this may be random. Appendix 9 specifies the 60 cases, 10 of which were mild anomalies.

Table 6. Three groups of congenital malformations where risks seemed to differ with the SSRI used. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) adjusted for year of birth, maternal age, parity, smoking and body mass index (BMI)

SSRI, Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; df, degrees of freedom.

a Risk ratio (observed/expected number) with exact 95% CI based on Poisson distributions.

For any cardiovascular defect, a significantly increased risk was seen after paroxetine and the estimates for the four SSRI drugs differed significantly. The increased risk for cardiovascular defects after paroxetine was based on 24 cases, 12 of which had VSDs or ASDs (seven with VSDs, four with ASDs, and one with both VSDs and ASDs). The risk increase for VSD and/or ASD is similar to that for all cardiovascular defects but is not statistically significant (RR 1.61, 95% CI 0.83–2.82). No increased risk was seen for VSD and/or ASD with any of the three other SSRIs. Finally, a significantly increased risk for hypospadias after exposure to paroxetine was seen.

To eliminate possible confounding factors from concomitant use of drugs with potential teratogenic properties or use of drugs given for conditions that may harm the embryo, infants were removed from the analysis if the mother had also reported taking any one of the following: insulin, antihypertensive drugs, drugs for asthma, systemic corticoids, drugs for thyroid disease. This left 88–90% of the cases for analysis. There were only minor changes in OR estimates but the OR for relatively severe malformations after exposure to fluoxetine decreased slightly (to 1.26) and lost statistical significance (95% CI 0.96–1.65) whereas the OR after exposure to paroxetine increased slightly to 1.31 and approached statistical significance (95% CI 0.98–1.76). For any cardiovascular defect, the OR after exposure to paroxetine increased to 1.81 (95% CI 1.19–2.76) whereas the OR did not change at all after exposure to fluoxetine (1.31, 95% CI 0.83–2.06). The OR for VSD or ASD after exposure to paroxetine (based on 12 cases) increased somewhat and became close to significant (1.79, 95% CI 0.99–3.22).

Discussion

Studies on the impact of antidepressant use during pregnancy have been made with different methodologies. Some rely on detailed information on drug use in a small number of patients, notably studies performed in teratology information centres. Others have used retrospective case–control studies, with the risk for recall bias and often relatively large non-response rates. A third set of studies have identified exposure from registers of prescribed drugs; these have provided data from a large number of studies but also carry the risk of exposure misclassification as it is not certain that a woman who had bought a drug did in fact use it during the organogenetic period. We have used the Swedish MBR, which contains exposure data based on interviews in early pregnancy and therefore prospectively related to delivery outcome. However, information on the amount of drugs taken and exact timing is lacking, which probably results in some dilution of the data. This should, however, only little affect risk estimates. Another advantage is that the data base is growing continuously and the results from early studies can be checked in follow-up studies. The principles of epidemiological studies of drug effects when used during pregnancy have been discussed previously in some detail (Källén, Reference Källén2005).

As in all similar studies, the problems encountered in multiple testing are important and every conclusion should be looked upon as a signal of further study on independent material. We therefore compared our findings with results from the published literature.

We found marked differences in the characteristics of women using antidepressants in early pregnancy when compared with other women who gave birth. This may confound the analysis, notably for variables such as preterm birth that are sensitive to such factors. Even if efforts were made to adjust for these confounders, the adjustments may have been incomplete. Thus, for instance, women using antidepressants smoke more than other women and the classification of smoking is relatively crude and may leave a residual confounding. Other confounders that could not be studied may interfere with the analysis, such as alcohol use. The most difficult confounder, much discussed in the literature, is the underlying pathology, notably maternal depression. We cannot distinguish between the effects of depression and drug treatment of depression. Women who used antidepressants also used some other drugs in excess, some of which could have a teratogenic effect. However, exclusion of their infants from analysis did not markedly affect the risk estimates for congenital malformations.

Relatively little is published about delivery diagnoses after antidepressant use. An increased risk for gestational hypertension and pre-eclampsia has been described by Toh et al. (Reference Toh, Mitchell, Louik, Werler, Chambers and Hernandez-Diaz2009), which is supported by our findings (Table 2), but other complications of pregnancy and delivery were also found after both early and later exposure, which indicates that many of the women who reported early use but did not got prescriptions during pregnancy from the antenatal care also used antidepressants later in pregnancy. Another possibility is that underlying psychiatric morbidity was of importance, as suggested by Toh et al. (Reference Toh, Mitchell, Louik, Werler, Chambers and Hernandez-Diaz2009).

The effects we found of antidepressant use on gestational duration agree with most results in the literature. We cannot tell whether this is a drug effect or an effect of underlying psychiatric pathology. After use later in pregnancy, the effect on preterm birth of TCAs and perhaps of SNRIs seems to be larger than that of SSRIs. This could be the result of different indications for drug use, or a specific drug effect. The same can be said about neonatal pathology, which basically agrees with what has been described in the literature. Similar differences, with a higher risk estimate after TCA than SSRI use, are seen for hypoglycaemia, respiratory diagnoses, low Apgar score, and jaundice. Our data support the association between SSRI use and PPHN.

The most clear-cut result concerning teratogenic properties of antidepressant drugs is the higher risk after clomipramine exposure than after SSRI or SNRI exposure. This risk seems to be restricted mainly to cardiovascular defects and was reported in previous studies of the same data set (Källén & Otterblad Olausson, Reference Källén and Otterblad Olausson2003). One explanation for this finding could be an inhibitory effect on a specific cardiac potassium current channel, expressed by the human ether-a-go-go-related gene (Källén, Reference Källén2007). There were some differences between the four main SSRI drugs. With respect to general teratogenicity, the data indicated a significantly high risk after fluoxetine but this effect may be spurious as the differences between the four drugs could be random. Scrutiny of malformation diagnoses after fluoxetine exposure (Appendix 9) shows no clustering of any specific condition. However, an excess of cardiovascular defects was seen after paroxetine exposure and the difference in risk between the four drugs was significant. Nevertheless, the excess may be random as many different drug–outcome combinations were studied, but this result agrees with some but not all data in the literature. The risk increase seems to be due to VSDs and/or ASDs but the numbers of each type are so low that no firm conclusion can be drawn. A new observation is an increased risk for hypospadias after SSRI exposure, again significantly stronger after paroxetine than after other SSRIs. It should be pointed out that even if a difference exists between the four SSRIs in teratogenicity, this could be due to confounding by indication as the drugs may be used under different conditions (Bar-Oz et al. Reference Bar-Oz, Einarson, Einarson, Boskovic, O'Brien, Malm, Berard and Koren2007).

One important aspect of the possible hazards associated with antidepressant use during pregnancy refers to possible long-term effects on child development. This aspect was not studied in the present investigation.

In summary, our analysis, which uses the largest data set available based on prospective exposure information, supports the idea that the use of antidepressants during pregnancy increases the risk for several pregnancy, delivery and neonatal complications. It is not possible to dissociate these effects from possible effects of the underlying psychiatric pathology. The teratogenic potential is low but probably stronger for TCA than for SSRI and SNRI exposure. A specific association between paroxetine use and infant cardiovascular defects is supported. A previously unknown association between SSRIs and hypospadias was found, which is particularly strong with the use of paroxetine.

Declaration of Interest

None.

Note

Supplementary material accompanies this paper on the Journal's website (http://journals.cambridge.org/psm).