Previous studies have provided evidence for the efficacy of two types of mentalization-based treatment (MBT) for borderline personality disorder (BPD): day hospital MBT (MBT-DH), a treatment involving day hospitalization of patients 5 days per week, and intensive outpatient MBT (MBT-IOP), an outpatient treatment program conducted 2 days per week (Bales et al., Reference Bales, van Beek, Smits, Willemsen, Busschbach, Verheul and Andrea2012, Reference Bales, Timman, Andrea, Busschbach, Verheul and Kamphuis2014; Barnicot & Crawford, Reference Barnicot and Crawford2019; Bateman & Fonagy, Reference Bateman and Fonagy1999, Reference Bateman and Fonagy2001, Reference Bateman and Fonagy2008, Reference Bateman and Fonagy2009; Jørgensen et al., Reference Jørgensen, Bøye, Boye, Jordet, Andersen and Kjolbye2013, Reference Jørgensen, Bøye, Andersen, Døssing Blaabjerg, Freund, Jordet and Kjølbye2014; Kvarstein et al., Reference Kvarstein, Pedersen, Urnes, Hummelen, Wilberg and Karterud2015; Laurenssen et al., Reference Laurenssen, Luyten, Kikkert, Westra, Peen, Soons and Dekker2018). However, only one trial has directly compared the two treatment programs. Smits et al. (Reference Smits, Feenstra, Eeren, Bales, Laurenssen, Blankers and Luyten2019) found that both MBT-DH and MBT-IOP were associated with substantial improvements on both primary and secondary outcome measures, representing moderate-to-large effect sizes 18 months after the start of treatment. Although MBT-DH was not superior to MBT-IOP in terms of changes on the primary outcome measure (symptom severity), MBT-DH showed a trend towards superiority on secondary outcome measures, particularly on measures of relational functioning. Longer-term follow-up data are thus needed to further determine the relative efficacy of MBT-DH and MBT-IOP.

As MBT aims to improve mentalizing, and improvements in mentalizing are thought to underlie ‘broaden-and-build’ cycles leading to improved emotion regulation, feelings of autonomy and agency, and improved capacity for relatedness (Fredrickson, Reference Fredrickson2001; Luyten & Fonagy, Reference Luyten, Fonagy, Holmes and Farnfield2014), patients in MBT are expected to show ongoing improvement after treatment termination. Consistent with this hypothesis, previous follow-up studies have shown that the gains made during the intensive treatment phase of MBT-DH were maintained and that patients continued to improve over 18-month and 5-year follow-up periods for the MBT-DH program (Bales et al., Reference Bales, Timman, Andrea, Busschbach, Verheul and Kamphuis2014; Bateman & Fonagy, Reference Bateman and Fonagy2001, Reference Bateman and Fonagy2008), although for MBT-IOP, ongoing improvement was not found in one 18-month follow-up study (Jørgensen et al., Reference Jørgensen, Bøye, Andersen, Døssing Blaabjerg, Freund, Jordet and Kjølbye2014).

Several studies have focused on the impact of treatment modality or intensity on treatment outcome in BPD. For instance, a non-randomized study by Bartak et al. (Reference Bartak, Andrea, Spreeuwenberg, Ziegler, Dekker, Rossum and Emmelkamp2011) investigated the differential effectiveness of three treatment modalities (inpatient, day hospital and outpatient treatment) and consequent varying degrees of treatment intensity for cluster B personality disorders, yielding somewhat inconclusive results. Although patients improved in all treatment modalities, at 18-month follow-up, inpatient treatment was associated with marginally significant better outcomes in terms of psychiatric symptoms, compared with outpatient treatment. There were no differences in terms of quality of life and interpersonal functioning (Bartak et al., Reference Bartak, Andrea, Spreeuwenberg, Ziegler, Dekker, Rossum and Emmelkamp2011). At 60-month follow-up, inpatient treatment was associated with slightly better outcomes compared with outpatient treatment in terms of quality of life, but not on other outcome measures (Horn et al., Reference Horn, Bartak, Meerman, Rossum, Ziegler and Busschbach2016). Another non-randomized study, by Chiesa, Fonagy, Holmes, and Drahorad (Reference Chiesa, Fonagy, Holmes and Drahorad2004), showed significantly better outcomes in a heterogeneous sample of patients with personality disorder in a step-down program compared with longer-term inpatient treatment and general psychiatric services. At 1- and 2-year follow-up, patients in the step-down group showed a greater improvement in symptom severity, social functioning and self-harming behaviours and reported less use of outpatient treatment and readmissions to psychiatric services after discharge. These findings were maintained at 6-year follow-up (Chiesa, Fonagy, & Holmes, Reference Chiesa, Fonagy and Holmes2006). Nevertheless, a more recent meta-analysis of psychotherapy for BPD by Cristea et al. (Reference Cristea, Gentili, Cotet, Palomba, Barbui and Cuijpers2017) found that neither treatment duration nor treatment intensity was related to treatment outcome. A number of recent randomized controlled trials are addressing the issue of treatment intensity (Juul et al., Reference Juul, Lunn, Poulsen, Sørensen, Salimi, Jakobsen and Simonsen2019; McMain et al., Reference McMain, Chapman, Kuo, Guimond, Streiner, Dixon-Gordon and Hoch2018), but these studies are still ongoing. Clearly, more research in this area is needed.

The current paper reports on the findings at 3-year follow-up from the abovementioned randomized clinical trial comparing MBT-DH and MBT-IOP for patients with BPD (Smits et al., Reference Smits, Feenstra, Eeren, Bales, Laurenssen, Blankers and Luyten2019). Because MBT-DH and MBT-IOP differ markedly in terms of treatment intensity, we expected that the tendency for MBT-DH to be superior to MBT-IOP would be more pronounced at 36-month follow-up, given the substantially higher dose of treatment.

Method

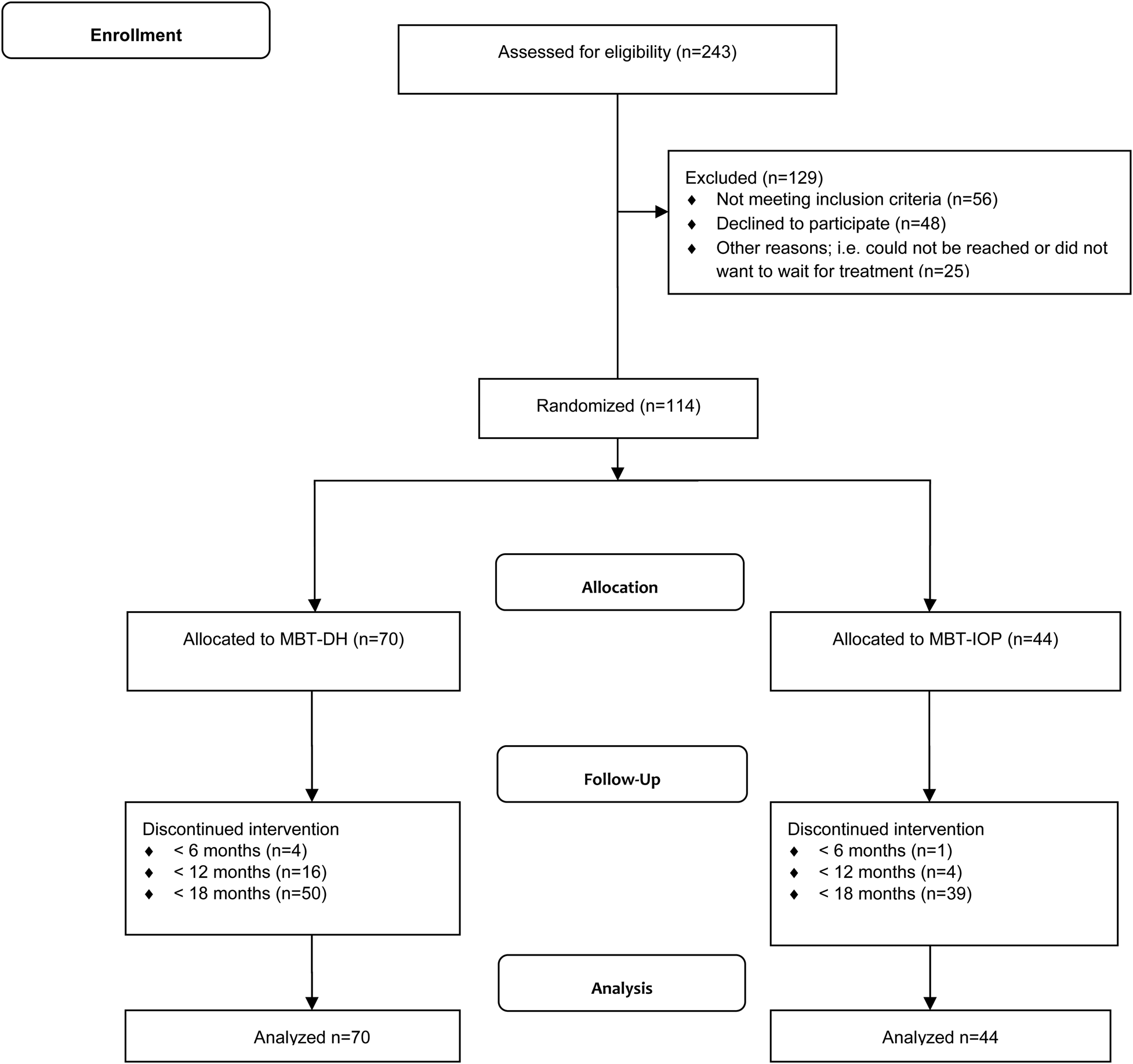

This study was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands (NL38571.078.12). A total of 114 patients from three sites in the Netherlands were randomized to MBT-DH (n = 70) or MBT-IOP (n = 44) and received treatment as allocated for a maximum duration of 18 months. Inclusion and exclusion criteria, patient characteristics and randomization procedures have been described in detail by Laurenssen et al. (Reference Laurenssen, Smits, Bales, Feenstra, Eeren, Noom and Verheul2014). All 114 patients included in the 18-month treatment outcome study (Fig. 1) were approached again for long-term follow-up assessments at 24, 30 and 36 months after the start of treatment. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Fig. 1. CONSORT flow diagram. MBT-DH, day hospital mentalization-based treatment; MBT-IOP, intensive outpatient mentalization-based treatment.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was symptom severity as assessed by the Global Severity Index of the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI; De Beurs, Reference De Beurs2011; Derogatis, Reference Derogatis1975). Secondary outcomes included severity of borderline symptoms as measured with the Personality Assessment Inventory (PAI-BOR; Distel, De Moor, & Boomsma, Reference Distel, De Moor and Boomsma2009); personality functioning as assessed by the Severity Indices of Personality Problems-Short Form (SIPP; Verheul, Reference Verheul2006; Verheul et al. Reference Verheul, Andrea, Berghout, Dolan, Busschbach, van der Kroft and Fonagy2008); interpersonal problems as assessed by the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems (IIP; Horowitz, Alden, Wiggins, & Pincus, Reference Horowitz, Alden, Wiggins and Pincus2000; Zevalkink et al. Reference Zevalkink, de Geus, Hoek, Berghout, Brouwer, Riksen-Walraven and Katzko2012); quality of life as assessed by the EQ-5D-3L (Brooks, Rabin, & de Charro, Reference Brooks, Rabin and de Charro2003); and frequency of suicide attempts and self-harm as assessed by the Suicide and Self-Harm Inventory (SSHI; Bateman and Fonagy, Reference Bateman and Fonagy2004). The intensity of care consumption during the follow-up period was based on the registered number of minutes of treatment at the research sites. To exclude terminative or administrative visits related to the previous intensive treatment phase from counting towards additional care consumption, a minimum of 180 registered treatment minutes after termination of the intensive treatment was assumed to be relevant care consumption.

Treatment interventions

A detailed description of MBT-DH and MBT-IOP is provided elsewhere (Smits et al., Reference Smits, Feenstra, Eeren, Bales, Laurenssen, Blankers and Luyten2019). Briefly, treatment components and features in MBT-DH and MBT-IOP are very similar, with weekly individual sessions in both programs, but the intensity of group therapy differs markedly. MBT-IOP involves two group therapy sessions per week, while MBT-DH entails a day hospital program 5 days per week, with nine group therapy sessions per week. Treatment adherence to the MBT model in the intensive treatment phase was rated as adequate by three independent raters and did not differ between MBT-DH and MBT-IOP. Overall dropout rate during the intensive treatment phase was 12%, n = 14, comprising one-sided termination of treatment by the patient (n = 12) or push-out by staff (n = 2), with no differences between the groups [n = 5, 11% for MBT-IOP and n = 9, 13% for MBT-DH; χ2(1) = 0.056, p = 0.813]. The duration of the main treatment phase was somewhat shorter in MBT-DH (mean = 14.3 months, s.d. = 4.2) compared with MBT-IOP [mean = 15.9 months, s.d. = 3.1; t(109) = 2.223, p = 0.028]. There were no differences between the groups in the proportion of patients using medication at baseline [χ2(1) = 0.001, p = 0.972], at 18-month follow-up [χ2(1) = 2.276, p = 0.131] or 36-month follow-up [χ2(1) = 0.185, p = 0.667].

After termination of the intensive treatment phase, patients were offered individually tailored follow-up care generally consisting of individual booster sessions of mentalizing therapy, crisis management or psychiatric consultation, as detailed in the MBT manual (Bateman, Bales, & Hutsebaut, Reference Bateman, Bales and Hutsebaut2014). Overall, 76.3% (n = 87) of patients received such care at their initial treatment site after ending the intensive treatment phase, with a trend for patients in MBT-DH to more often receive follow-up care (n = 58, 82.9%) than patients in MBT-IOP [n = 29, 65.9%; χ2(1) = 3.41, p = 0.065]. Additionally, for patients who received follow-up care, the intensity of this care was significantly higher in the MBT-DH group (median = 82 h) than in the MBT-IOP group (median = 51 h; Mann–Whitney U = 1049.00, z = –2.04, p = 0.041), with large individual variability in both groups (range 3–350 h).

Statistical analyses

Differences in demographic and clinical features at baseline were investigated using two-tailed χ2 tests and independent sample t tests, as appropriate. Mann–Whitney U tests were used to examine differences in follow-up care consumption.

Multilevel modelling was used to examine treatment outcomes over time to best accommodate the missing data that are an inevitable feature of longitudinal follow-up and to deal with the dependency of repeated measures within subjects over time; this was conducted using the XTMIXED procedure of Stata Statistical Software Release 12. All outcome analyses were based on the intention-to-treat principle. Time points were coded −6, −5, −4, −3, −2, −1 and 0, implying that regression coefficients involving time measured the rate of change from baseline to 36-month follow-up and regression intercepts referenced group differences at the last time point. SSHI scores were log-transformed because they were positively skewed. Maximum likelihood was used to assess whether random or fixed slopes should be assumed in models for each outcome variable. Subsequently, quadratic and cubic time variables were added to the model if likelihood ratio tests showed a significant improvement in fit.

In interpreting the multilevel models, a significant main effect of time(polynomials) represents significant differences over the course of time independent of group; intercepts reference potential significant group differences at 36 months after the start of treatment. Finally, significant interaction effects between group and (any polynomial of) time represent significant differences in the slopes of MBT-DH compared with MBT-IOP, and hence significant differences in the trajectories of change over time.

Reported estimates and Cohen's d effect sizes (Cohen, Reference Cohen1988) were based on predicted values. The a priori set superiority margin was d ⩾ 0.50, as this represents a clinically meaningful difference in the treatment of BPD (Laurenssen et al., Reference Laurenssen, Luyten, Kikkert, Westra, Peen, Soons and Dekker2018; Smits et al., Reference Smits, Feenstra, Eeren, Bales, Laurenssen, Blankers and Luyten2019). Furthermore, clinically significant change was calculated for symptom severity and borderline symptomatology. Patients were classified into the following categories: (1) recovered (i.e. statistically reliable change and movement from a dysfunctional range to a functional range), (2) improved (i.e. statistically reliable change in the direction indicative of improvement without crossing the cut-off); (3) unchanged (i.e. no statistically reliable change), (4) deteriorated (i.e. statistically reliable change in the opposite direction to that indicative of improvement) and (5) relapsed (i.e. statistically reliable change in the opposite direction to that indicative of improvement and movement from a functional to a dysfunctional range). To deal with missing data, recovery scores were based on predicted estimates of multilevel modelling. Following Jacobson and Truax (Reference Jacobson and Truax1991), reliable change (RC) from baseline to 18 months, baseline to 36 months and 18–36 months after the start of treatment was computed based on the formula RC = 1.96 × √2(s.e.)2. To calculate the standard error of measurement (s.e.), Cronbach's α of 0.97 was used for the BSI (De Beurs, Reference De Beurs2011) and 0.81 for the PAI-BOR (Distel et al., Reference Distel, De Moor and Boomsma2009) based on the following formula: s.e. = √(1-α). The cut-off score for movement from a dysfunctional to a normative range was based on the following formula: [(s.d.normal × M clinical) + (s.d.clinical × M normal)]/(s.d.normal × s.d.clinical). Means and standard deviations for the clinical and non-clinical populations were based on values reported in the manual of the Dutch version of the BSI (De Beurs, Reference De Beurs2011). For the PAI-BOR, means and standard deviations for the non-clinical population were based on norms of Distel et al. (Reference Distel, De Moor and Boomsma2009), and respective values for the clinical population were based on our own sample. Owing to missing data, clinically significant change could not be computed for all participants: it was computed for n = 112 participants on the BSI and n = 111 on the PAI-BOR (Table 1). The χ2 tests were used to determine whether MBT-DH and MBT-IOP differed in terms of recovery as calculated from baseline to 36 months after the start of treatment and from 18 to 36 months.

Table 1. Predicted means, results from multilevel models and effect sizes 36 months after the start of treatment on primary and secondary outcome measures for patients randomly assigned to intensive outpatient mentalization-based treatment (MBT-IOP) (n = 44) or day hospital mentalization-based treatment (MBT-DH) (n = 70)

MBT-IOP, intensive outpatient mentalization-based treatment; MBT-DH, day hospital mentalization-based treatment; GSI, Global Severity Index of the Brief Symptom Inventory; SIPP, Severity Indices of Personality Problems; PAI-BOR, Personality Assessment Inventory – Borderline Personality Disorder section; EQ-5D-3L, EuroQol-5D-3L; IIP, Inventory of Interpersonal Problems; SSHI, Suicide and Self-Harm Inventory. Linear/quadratic/cubic change represent main effects of (polynomials of) time and indicate changes over time independent of group; Δ linear/quadratic/cubic change, interaction term of time (polynomial) with group indicating differential change of MBT-DH compared to MBT-IOP over time; Δ group 36 months, difference of MBT-DH compared to MBT-IOP at 36 months; ES, effect size by means of Cohen's d.

*p < 0.05 ** p < 0.01 *** p < 0.001.

Randomization, missing data and sensitivity analyses

There were no significant differences between the two treatment groups at baseline, except for a higher percentage of patients who reported self-harm at baseline in MBT-IOP (63%) compared with MBT-DH (42%), χ2(1) = 3.96, p < 0.001. The proportion of missing data increased somewhat with each follow-up assessment owing to difficulties in contacting patients who were no longer in treatment, and ranged from 53% to 58% depending on the outcome measure and follow-up time point. Overall, 61% of patients completed at least one of the three follow-up assessments on the primary outcome measure. There was no difference between MBT-IOP and MBT-DH in terms of the number of patients who completed at least one follow-up assessment: n = 27 (61%) for MBT-IOP and n = 42 (60%) for MBT-DH [χ2(1) = 0.021, p = 0.885]. There were also no significant baseline differences between patients who completed a follow-up assessment and those who did not. This suggests that there was no selective study drop-out as a function of baseline severity.

Although multilevel modelling is quite robust in dealing with missing data, we re-ran all analyses using state-of-the-art data imputation procedures as described in Smits et al. (Reference Smits, Feenstra, Eeren, Bales, Laurenssen, Blankers and Luyten2019). These analyses yielded similar results, hence only results on the non-imputed data set are reported. Results on the imputed data are available upon request from the first author.

We also performed completer analyses, excluding treatment drop-outs using the pre-defined criterion of one-sided termination of treatment by the patient or push-out by staff (n = 14). These analyses yielded similar results as the intention-to-treat analyses for all outcome measures (see online Supplemental Table S1).

Results

Primary outcome

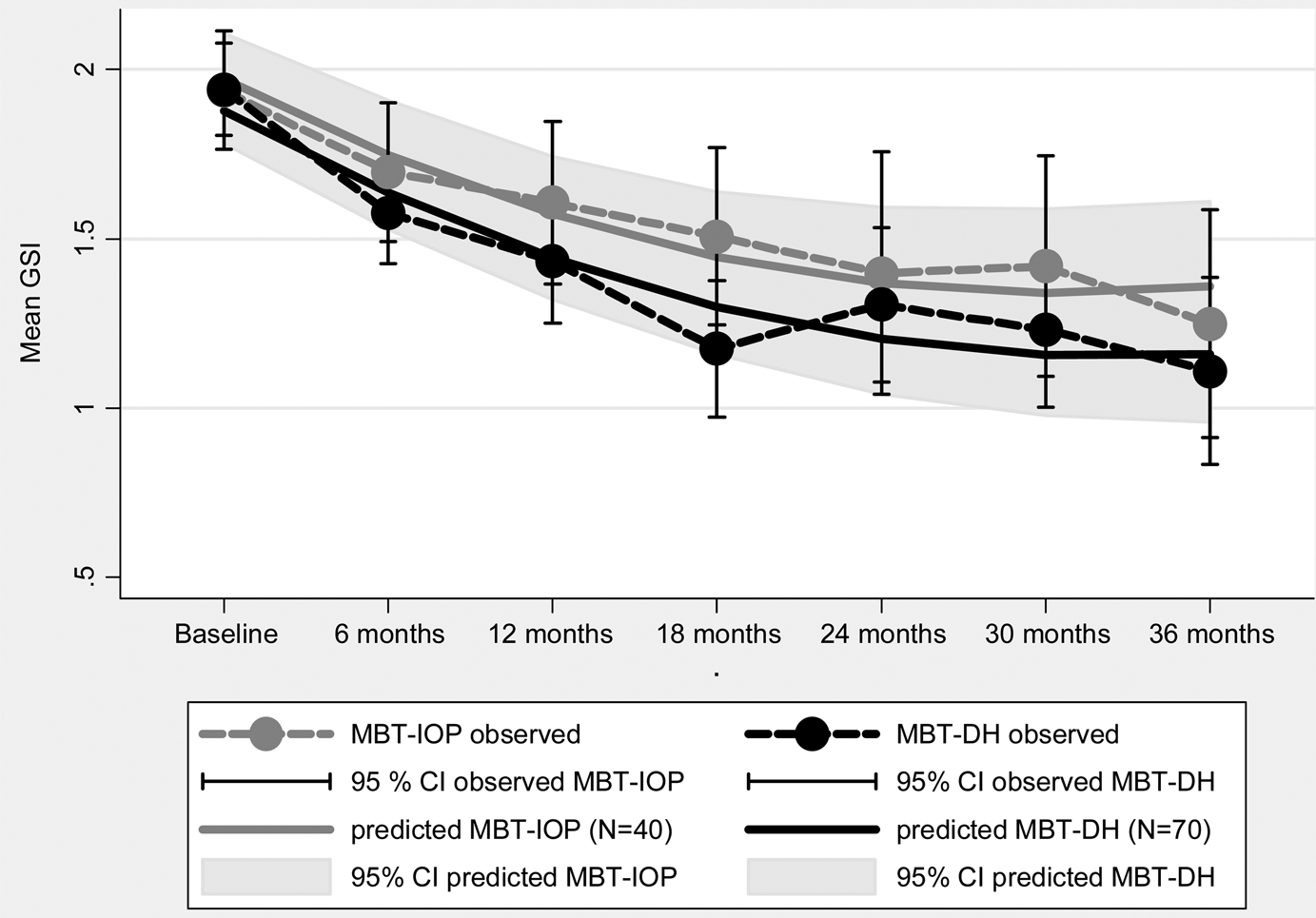

Improvement over time in terms of symptom severity between baseline and 36-month follow-up was statistically significant, representing large effect sizes in both MBT-IOP (d = 1.00) and MBT-DH (d = 1.12). There was no significant difference between the two groups at 36 months after the start of treatment [β = –0.20, 95% CI (–0.62 to 0.22), z = –0.93, p = 0.350], nor did the rate of change differ between the two groups [β = –0.02, 95% CI (–0.09 to 0.05), z = –0.51, p = 0.610]. The between-group effect size of d = 0.26 also indicated that MBT-DH was not superior to MBT-IOP in terms of improvement in symptom severity based on the a priori specified clinically meaningful Cohen's d ⩾ 0.5 margin at 36 months after the start of treatment (Table 1) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Observed and predicted Global Severity Index scores from baseline to 36 months after the start of treatment for intensive outpatient mentalization-based treatment (MBT-IOP) (n = 44) and day hospital mentalization-based treatment (MBT-DH) (n = 70) with 95% confidence intervals.

Secondary outcomes

Likewise, no significant differences were observed for any of the secondary outcome measures between the two groups at 36 months after the start of treatment (Table 1). Between-group effect sizes were small, with the exception of quality of life as measured with the EQ-5D-3L. Patients in MBT-DH showed higher scores than patients in MBT-IOP on this measure (d = 0.55), although this difference did not reach significance in the multilevel model. Yet, significant interaction effects between time(polynomials) and group indicated significant differences in terms of a differential rate of change between patients in MBT-DH and MBT-IOP on several other secondary outcome variables, suggesting differences in trajectories of improvement between the treatment groups. This was the case for several domains of personality functioning as assessed by the SIPP (identity integration, self-control, and relational capacities), borderline symptomatology as assessed by the PAI-BOR, and interpersonal problems as assessed by the IIP (Table 1). For all these secondary outcome measures, patients in MBT-DH maintained treatment gains made in the first 18 months of treatment or showed small additional gains, as represented by small within-group effect sizes from 18- to 36-month follow-up (range d = –0.08 to 0.24). Patients in MBT-IOP, by contrast, showed clear continued improvement on these outcome measures during the follow-up period, as is also shown by medium within-group effect sizes between 18 and 36 months (range d = 0.29–0.56). For relational functioning (SIPP relational capacities and IIP interpersonal problems), patients in MBT-IOP even showed a larger improvement during the follow-up period compared with the active treatment phase, whereas patients in MBT-DH did not show continued improvement from 18 to 36 months after the start of treatment, in terms of effect sizes.

Clinically significant change

In terms of symptom severity as assessed by the BSI, for the two treatment groups combined, 83% of patients (n = 93) were categorized as improved at 36-month follow-up, over a quarter of whom (n = 25, 26.9%) were classified as recovered. A small proportion of patients (n = 16, 14.3%) did not show reliable change and three patients (2.7%) deteriorated over the course of the 36-month follow-up period. There were no differences between MBT-IOP and MBT-DH at 18 months [χ2(2, n = 112) = 1.75, p = 0.418] or 36 months [χ2(3, n = 112) = 5.43, p = 0.143] after the start of treatment in terms of clinically significant change. Looking specifically at the follow-up period from 18 to 36 months, 95 patients maintained their initial improvement (84.8% unchanged), 12 patients continued to improve with additional reliable change (10.7%) and four patients deteriorated (3.6%). There were no significant differences in clinically significant change from 18 to 36 months between MBT-DH and MBT-IOP [χ2(3, n = 112) = 1.6816, p = 0.641] (Table 2).

In terms of borderline symptomatology (PAI-BOR), nearly all patients (n = 108, 97.3%) improved at 36-month follow-up, more than 50% of whom (n = 60, 55.6%) could be classified as recovered. Three patients who had shown improvement at 18 months after the start of treatment showed deterioration at 36-month follow-up. There were no differences between MBT-IOP and MBT-DH at 18 months [χ2(1, n = 111) = 1.33, p = 0.248] or 36 months [χ2(3, n = 111) = 3.18, p = 0.204] after the start of treatment in terms of clinically significant change on the PAI-BOR. Looking specifically at the follow-up period from 18 to 36 months, 89 patients showed additional reliable change (80.1% improved or recovered), 11 patients (9.9% unchanged) maintained their initial improvement and 11 patients (9.9%) showed deterioration, among whom one patient relapsed. Over the follow-up period from 18 to 36 months, MBT-DH and MBT-IOP differed significantly in terms of clinically significant change on borderline symptomatology [χ2(4, n = 111) = 15.70, p = 0.003], with more patients in MBT-IOP showing continued improvement or recovery during follow-up [n = 39, 92.9% improved or recovered in MBT-IOP v. n = 50, 72.4% in MBT-DH; χ2 (1) = 7.7021, p = 0.006]. This observation is consistent with findings from the multilevel models indicating that patients in MBT-IOP showed greater continued improvement during the follow-up period than patients in MBT-DH (Table 2).

Table 2. Distribution over categories of recovery based on symptom severity (GSI) and borderline symptomatology (PAI-BOR) for patients randomly assigned to intensive outpatient mentalization-based treatment (MBT-IOP) or day hospital mentalization-based treatment (MBT-DH)

MBT-IOP, intensive outpatient mentalization-based treatment; MBT-DH, day hospital mentalization-based treatment; GSI, Global Severity Index of the Brief Symptom Inventory; PAI-BOR, Personality Assessment Inventory – Borderline Personality Disorder section.

Recovery scores are calculated between baseline and 18 months, between baseline and 36 months, and between 18 and 36 months after the start of treatment. Recovered, statistically reliable change and movement from a dysfunctional range to a functional range. Improved, statistically reliable change in the direction indicative of improvement without crossing cut-off. Unchanged, no statistically reliable change. Deteriorated, statistically reliable change in the opposite direction of that indicative of improvement. Relapsed, statistically reliable change in the opposite direction of that indicative of improvement and movement from a functional to a dysfunctional range.

Discussion

Patients in both MBT-DH and MBT-IOP maintained the substantial improvements made during the intensive treatment phase, and continued to improve during long-term follow-up from 18 to 36 months after the start of treatment. In terms of clinically significant change on the primary outcome measure of symptom severity, 83% of patients improved over this period, over a quarter of whom (26.9%) met criteria for recovery – that is, they moved from a dysfunctional to a functional range on symptom severity. For borderline symptomatology specifically, 97% of patients improved, and over half of these patients could be classified as recovered. Contrary to our hypothesis, but consistent with the outcome results at 18 months, MBT-DH did not show superiority in terms of reduction of symptom severity at 36 months after the start of treatment. Similarly, there were no apparent differences between the two groups in terms of clinically significant change over the course of 36 months for both symptom severity and borderline symptomatology. The trend towards superiority of MBT-DH on several secondary outcome measures, specifically those in the domain of relational functioning, observed at 18 months after the start of treatment, was no longer evident at 36 months.

Furthermore, trajectories of change during follow-up were notably different for patients in MBT-DH and MBT-IOP. Patients in MBT-DH tended to show the largest improvement during the intensive treatment phase, and these gains were largely maintained or slightly increased during the follow-up period. By contrast, whereas the rate of improvement in MBT-IOP was smaller than that in MBT-DH during the first 18 months, patients in MBT-IOP showed larger additional gains during follow-up. In other words, patients in MBT-IOP caught up with patients in MBT-DH during follow-up. This differential trajectory of change was most apparent in the domain of relational functioning, with MBT-DH patients showing faster improvement initially that seemed to level off during follow-up, whereas MBT-IOP patients showed a larger improvement during follow-up. This finding is consistent with our earlier hypothesis (Smits et al., Reference Smits, Feenstra, Eeren, Bales, Laurenssen, Blankers and Luyten2019), based upon work by Fonagy, Luyten, and Allison (Reference Fonagy, Luyten and Allison2015), that the ‘safety net’ and scaffolding provided by the day hospital setting may result in earlier improvements in mentalizing and social learning because it may provide patients with greater opportunity to generalize therapeutic gains within a relatively safe social context. In contrast, patients in MBT-IOP are less likely to have access to a supportive environment, and they may have to face everyday problems related to relationships, work and social activities sooner than patients in a day hospital program. Consequently, it may take more time for ‘virtuous cycles’ associated with increasing mentalizing and social learning to emerge for these patients. However, once these cycles are established, these patients seem to be able to catch up with patients in MBT-DH.

Importantly, the greater improvements in MBT-IOP during the follow-up period were not related to a higher intensity of follow-up care. In fact, patients in MBT-DH received follow-up care more often and at a higher intensity than those in MBT-IOP. Taken together, from a developmental psychopathology perspective, these results suggest that recovery in patients in MBT-IOP may follow a more ‘natural’ course, with patients being challenged from the start of treatment to generalize the capacities they acquire in terms of mentalizing, attachment and social learning to their everyday life. Patients in MBT-DH, by contrast, may show faster improvement in these capacities because they mainly function within a relatively protected environment, but then may face the same problem when they are no longer in the day hospital setting – that is, how to generalize what they have learned in treatment to dealing with the everyday challenges of life. Further research is needed to investigate these hypotheses.

There are important limitations that should be kept in mind when interpreting the current results. First, the proportions of missing data at the 24-, 30- and 36-month follow-up points were substantial, although this limitation is somewhat mitigated by the fact that imputation analysis showed comparable results. Moreover, there were no differences in the percentages of missing data between the two treatment groups, and completer analyses showed similar results. Yet, it cannot be ruled out that missingness might be related to factors related to treatment outcome. Second, the superiority margin set in this trial corresponded to a medium effect size. It could be argued that smaller between-group differences may be clinically relevant; further research in larger samples is needed to address this issue. Third, there was some evidence for differential care consumption between MBT-IOP and MBT-DH after the end of the main treatment phase. However, we do not have systematic data on the exact nature of the care that was provided at the treatment sites during follow-up, or on in-session adherence to the MBT model outside the main treatment phase, although the same therapists were involved in providing care during follow-up as in the main treatment phase. In addition, we did not use data on treatment-seeking outside the treatment site for this study. This issue will be addressed in more detail in future cost-effectiveness analyses. Finally, use of medication may have influenced treatment outcomes, although there were no differences between the two treatment arms in the proportion of patients using medication at baseline or 18 or 36 months after the start of treatment.

Despite these limitations, the results of this study suggest that MBT-IOP and MBT-DH are both valuable treatment options for patients with BPD. However, cost-effectiveness analyses are needed, given the large differences in intensity and cost of the two treatments, to further investigate whether MBT-IOP is more cost-effective than MBT-DH. As observations from an organizational perspective have shown that MBT-DH is more difficult to implement (Bales, Verheul, & Hutsebaut, Reference Bales, Verheul and Hutsebaut2017), without support for its cost-effectiveness, it will be hard to maintain MBT-DH as a viable treatment option. In terms of the optimization of use of health care resources, the implementation of less intensive treatment programs might enable more patients to be treated with similar resources, reducing the iatrogenic harm related to the choice of less ideal treatment options or long waiting lists. Still, however, MBT-DH may be more (cost-)effective in specific subgroups of BPD patients (e.g. those with more severe and chronic psychosocial problems), including those for whom MBT-IOP might even be contraindicated. Therefore, more research is needed to identify potential factors that might predict differential treatment outcomes. For example, for patients who are highly chaotic and fragmented, the stronger holding environment and structure provided by an intensive day hospital setting may be more effective than an outpatient setting. On the basis of the current results, we also hypothesize that an assessment of the social environment and opportunities for creating a sufficiently benign context in which treatment gains can be generalized might be important to consider when determining which treatment is likely to work best for individual patients.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720002123.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the research assistants for collecting the data. We are also very grateful to the patients who participated in this study.

Author contributions

PL, RV, JJMD, JJVB, JHK, DLB and DJF designed the study and directed the trial. DLB and PL were responsible for MBT quality aspects within the trial. DJF and MLS coordinated the trial and data collection. MLS, ZL and JJMD were responsible for trial implementation and data collection at the treatment sites. MLS, MB and PL performed the data analysis. MLS, DJF, JJVB, RV and PL interpreted the data and drafted the article. JHK, DLB, MB, JJMD, ZL and JHK revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final version to be submitted for publication.

Financial support

This research was supported in part by a grant from ZonMw (grant no. 171202012).

Conflict of interest

PL and DLB have been involved in the development, training and dissemination of mentalization-based treatment. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. This study was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands (NL38571.078.12).