Introduction

Deficits in working memory and executive functions are currently considered among the major features of schizophrenia. They are also a major determinant of community functioning and rehabilitation abilities, which are important to take into account in the development of cognitive enhancement therapies (Lysaker & Bell, Reference Lysaker and Bell1995; Corrigan, Reference Corrigan2006). Executive function is a multifaceted construct involving various subprocesses such as cognitive inhibition, set shifting or flexibility and monitoring (Baddeley & Della Sala, Reference Baddeley, Della Sala, Roberts, Robbins and Weiskrantz1998). Schizophrenia is also a heterogeneous construct involving a variety of symptoms traditionally grouped into negative and positive symptoms (Crow, Reference Crow1980).

Although relationships between negative, or psychomotor poverty symptoms (poverty of speech, decreased spontaneous movements and blunting of affect), and executive functions have been consistently described (Norman et al. Reference Norman, Malla, Morisson-Stewart, Helmes, Williamson, Thomas and Cortese1997; Cameron et al. Reference Cameron, Oram, Geffen, Kavanagh, McGrath and Geffen2002; Pantelis et al. Reference Pantelis, Harvey, Plant, Fossey, Maruff, Stuart, Brewer, Nelson, Robbins and Barnes2004; Guillem et al. Reference Guillem, Ganeva, Pampoulova and Stip2005a; Donohoe et al. Reference Donohoe, Corvin and Robertson2006), the links with positive symptoms are far less clear. Most likely, the latter observation can be attributed to the heterogeneity of positive symptoms. In effect, when dissociating positive symptoms into disorganization (thought disorders, inappropriate affect, poverty of content of speech and disorganized behavior) and reality distortion (delusions and hallucinations) dimensions, studies have consistently reported correlations between disorganization and executive dysfunction, particularly inhibition (e.g. Stroop test) (Baxter & Liddle, Reference Baxter and Liddle1998; Cameron et al. Reference Cameron, Oram, Geffen, Kavanagh, McGrath and Geffen2002; Lucas et al. Reference Lucas, Fitzgerald, Redoblado-Hodge, Anderson, Sanbrook, Harris and Brennan2004; Pantelis et al. Reference Pantelis, Harvey, Plant, Fossey, Maruff, Stuart, Brewer, Nelson, Robbins and Barnes2004; Guillem et al. Reference Guillem, Ganeva, Pampoulova and Stip2005a; Leeson et al. Reference Leeson, Simpson, McKenna and Laws2005; Takahashi et al. Reference Takahashi, Iwase, Nakahachi, Sekiyama, Tabushi, Kajimoto, Shimizu and Takeda2005). On the other hand, reality distortion has often been reported not to be associated with executive dysfunction (Malla et al. Reference Malla, Norman, Morrison-Stewart, Williamson, Helmes and Cortese2001; Cameron et al. Reference Cameron, Oram, Geffen, Kavanagh, McGrath and Geffen2002; Lucas et al. Reference Lucas, Fitzgerald, Redoblado-Hodge, Anderson, Sanbrook, Harris and Brennan2004), but a few studies showed associations with classical measures of executive functions (e.g. set shifting test or Wisconsin Card Sorting Test; WCST) (Guillem et al. Reference Guillem, Ganeva, Pampoulova and Stip2005a; Rocca et al. Reference Rocca, Castagna, Marchiaro, Rasetti, Rivoira and Bogetto2006) or interactions between positive symptoms, mostly delusions, and a lack of cognitive flexibility in relation to negative symptoms or dysphoria (Donohoe et al. Reference Donohoe, Corvin and Robertson2006; Lysaker & Hemmersley, Reference Lysaker and Hemmersley2006).

These inconsistencies are somewhat puzzling, particularly since the cognitive constructs developed to account for hallucinations and delusions appear closely related to executive dysfunctions. For instance, delusions have been associated with an attentional bias toward threatening information (Blackwood et al. Reference Blackwood, Howard, Bentall and Murray2001), to a tendency to attribute meaning according to rigid conceptual expectations (Magaro, Reference Magaro1980). Delusional patients are overconfident in their response and request less information before reaching a decision (i.e. ‘jump to conclusions’) (Garety et al. Reference Garety, Hemley and Wessely1991). All these processes point towards a lack of cognitive flexibility (Garety et al. Reference Garety, Fowler, Kuipers, Freeman, Dunn, Bebbington, Hadley and Jones1997, Reference Garety, Kuipers, Fowler, Freeman and Bebbington2001). On the other hand, hallucinations have been associated with an abnormal influence of memories of previous input on current perception, which leads to intrusion of unintended information into consciousness (Frith, Reference Frith1979, Reference Frith1992; Hemsley, Reference Hemsley1993). In the same line, other authors proposed that hallucinations arise from a cognitive ‘dissonance’, or conflict, caused by the incompatibility between intrusive thoughts and beliefs (Morrison et al. Reference Morrison, Haddock and Tarrier1995; Baker & Morrison, Reference Baker and Morrison1998). Both views clearly emphasize monitoring difficulties and exaggerated sensitivity to interfering information characteristic of executive dysfunctions. So, the question arises as to why most studies using classical executive tests failed to demonstrate consistent correlations between executive dysfunctions and positive symptoms. A first possibility, as suggested above, is that the heterogeneity and interactions between disorganization, delusion and hallucination symptoms may have precluded the finding of specific associations with discrete cognitive processes involved in executive functions. For instance, in schizophrenia delusions and hallucinations are generally related by their content, but the fact that they can occur independently in other psychiatric or neurological diseases implies that they reflect distinct mechanisms. These symptoms have been also considered as secondary to the core pathological process expressed as disorganization in early descriptions of the illness (Bleuler, Reference Bleuler1911). Positive symptoms, mostly delusions, are also correlated with low self-esteem and depression (Norman & Malla, Reference Norman and Malla1994; Freeman et al. Reference Freeman, Garety, Fowler, Kuipers, Dunn, Bebbington and Hadley1998; Norman et al. Reference Norman, Malla, Cortese and Diaz1998; Garety & Freeman, Reference Garety and Freeman1999; Birchwood et al. Reference Birchwood, Meaden, Trower, Gilbert and Plaistow2000; Garety et al. Reference Garety, Kuipers, Fowler, Freeman and Bebbington2001; Guillem et al. Reference Guillem, Pampoulova, Stip, Lalonde and Todorov2005b). The fact that these negative emotional states overlap with negative symptom measures may have thus biased the findings toward correlations of executive function with negative symptoms. Finally, it is possible that that the assessment of executive functions using rather global measures such as the Stroop test or WCST do not distinguish adequately the contribution of specific processes such as inhibition and flexibility. This is not to mention the potentially confounding effects of factors such as antipsychotic medication (acting mostly on positive symptoms), age or duration of illness (positive symptoms decrease with chronicity).

In this study, we chose to use an older, though reliable, paradigm developed by Wickens (Wickens et al. Reference Wickens, Born and Allen1963; Wickens, Reference Wickens1970) to demonstrate, in healthy subjects, the role of proactive interference build-up and release in working memory. The typical procedure in this paradigm is as follows: in the first three or four trials, subjects are required to memorize lists of items drawn from a single semantic category (e.g. animals). These trials comprise the proactive interference build-up phase. Recall performance declines as a function of increasing interference from earlier trials. On trial five, subjects are presented with a list of items drawn from a different category (e.g. vegetables). The performance gets a dramatic boost, due to the ‘release’ from proactive interference. Therefore, performance on the build-up phase provides a measure of interference sensitivity, which according to the above could be related to hallucinations. The number of intrusions during this phase provides an additional measure of inhibition failure that could be related to disorganization. Finally, performance in the release condition provides a measure of flexibility, i.e. the capacity to shift from a category to another that seems more associated with delusions. The potential confounding effects of the interrelationships between symptoms or with other variables (age, illness duration, depression and medication dose) were also taken into account in the analysis of the association between symptoms and executive function measures.

Method

Subjects

Ninety-six patients meeting DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia, confirmed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (First et al. Reference First, Spitzer, Gibbon and Williams1996), signed an informed consent to participate in this study. The patients were in the stable phase of the illness and were receiving out-patient treatment in the urban community of Montreal. Clinical stability was defined as no change in medication in the last month (Lysaker et al. Reference Lysaker, Bell, Kaplan and Bryson1998). General exclusion criteria included age <18 years or >59 years, past or present neurological disorder and non-compliance with testing procedures. Table 1 describes the demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients.

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics

s.d., Standard deviation; CPZ, chlorpromazine; BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; DISORG, disorganization; BIZ-DEL, bizarre delusions; AUD-HAL, auditory hallucinations; DIM-EX, diminished expression; CDSS, Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia; W-IB, interference sensitivity; W-IR, flexibility; W-IN, inhibition.

n=96. Values are given as mean (s.d.).

a Percentage correct recall on the first four lists.

b Percentage correct recall on the fifth list.

c Number on the first four lists.

Symptom and dimensional ratings

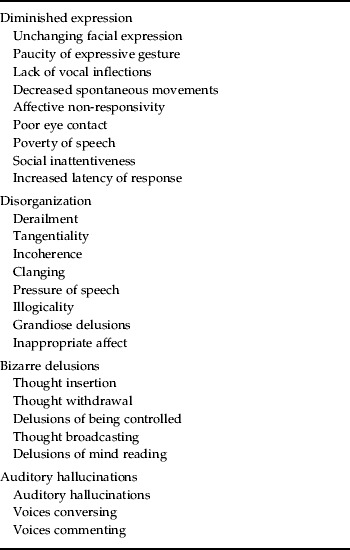

A research assistant trained with videotapes assessed patients' symptomatology using the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale to assess patients' global illness severity. The Scale for Assessment of Positive Symptoms and the Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms (Andreasen, Reference Andreasen1984a, Reference Andreasen b ) were used to assess specific symptoms. These scales were chosen as the most often used in analyses of the dimensional structure of schizophrenia symptomatology and its relationship with cognitive functions (Liddle & Morris, Reference Liddle and Morris1991; Cuesta & Peralta, Reference Cuesta and Peralta1995; Norman et al. Reference Norman, Malla, Morisson-Stewart, Helmes, Williamson, Thomas and Cortese1997; Baxter & Liddle, Reference Baxter and Liddle1998; Guillem et al. Reference Guillem, Bicu, Bloom, Wolf, Desautels, Lalinec, Kraus and Debruille2001, Reference Guillem, Ganeva, Pampoulova and Stip2005a). For each patient, scores were then calculated for ‘disorganization’ (DISORG), ‘bizarre delusions’ (BIZ-DEL), ‘auditory hallucinations’ (AUD-HAL) and ‘diminished expression’ (DIM-EX), i.e. negative symptoms, as the sum of items selected based on the dimension model proposed by Toomey et al. (Reference Toomey, Kremen, Simpson, Samson, Seidman, Lyons, Faraone and Tsuang1997). This model has been chosen, because it proposes a finer description of the symptomatology than the usual three-dimensional model. Particularly relevant in this study, it distinguishes delusions and hallucinations. It also proved to be more accurate for distinguishing the cognitive correlates of dimensional scores (Guillem et al. Reference Guillem, Bicu, Bloom, Wolf, Desautels, Lalinec, Kraus and Debruille2001, Reference Guillem, Ganeva, Pampoulova and Stip2005a). The scores are presented in Table 1 and the item composition of the dimensions is in Appendix 1.

A subsample of 41 patients was also evaluated for depression using the Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia (Addington et al. Reference Addington, Addington and Maticka-Tyndale1993). This scale, derived from the Present State Examination and Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, has been specifically developed for assessing depressive symptoms in schizophrenia patients. It has been shown to be reliable and valid, as well as congruent with self-report scales (e.g. Beck Depression Inventory) in distinguishing depression from negative and extra-pyramidal symptoms. The scores are presented in Table 1.

Wickens' test for proactive interference and release

Five lists of eight one- or two-syllables common words were constructed. Items of four lists used for interference build-up were drawn from the same category: animals (e.g. tiger, cow). Items of the fifth list used for interference release were drawn from another category: body parts (e.g. foot, finger). The patients were asked to listen attentively while the experimenter read the list aloud (rate: one word/s). They were instructed to count backward (delay of 15 s) by three starting from a random number given by the experimenter after the end of the list, before trying to recall every word they could remember.

The variables used in the analyses were the mean proportion (%) of correct responses (interference build-up; W-IB), the number of intrusions for the first four lists (W-IN) and the proportion (%) of correct responses for the fifth list (interference release; W-IR).

Data analysis

A first analysis was carried out through two-tailed Pearson's correlation to assess the relationships between symptom dimension scores as well as the associations between these score and other potentially confounding variables, i.e. depression, age, education, illness duration and antipsychotic dose.

The relationships between symptom scores and executive function measures were analyzed in two consecutive steps using stepwise regression analyses. In Step 1, the three cognitive measures were entered as explanatory variables to determine their associations with each symptom score separately. Step 2 was carried out using partial regressions to control for the potentially confounding effects of the symptom interrelationships and of other related variables as determined in the first correlation analysis. The analysis of variance results are provided in the text; the standardized regression coefficient (β) and significance levels are presented in the results Tables.

Results

The results from the correlation analysis showed that the three dimensions of the positive symptomatology, i.e. DISORG, BIZ-DEL and AUD-HAL, are strongly inter-correlated (Table 2). There was, however, no significant correlation between positive symptom dimensions and negative symptoms (DIM-EX), but a significant positive correlation was observed between BIZ-DEL and depression scores.

Table 2. Correlations between symptom dimensions

DIM-EX, Diminished expression; DISORG, disorganization; BIZ-DEL, bizarre delusions; AUD-HAL, Auditory hallucinations; n.s., not significant; CDSS, Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia.

* p=0.009, ** p<0.0005. All other correlations are non-significant.

The correlations with the other potentially confounding variables only revealed a positive relationship between antipsychotic dose and both BIZ-DEL (R0=0.27, p=0.008) and AUD-HAL scores (R0=0.31, p=0.003).

The mean recall performances of the patients on the five lists are presented in Fig. 1. The shape follows the classical curves obtained in healthy subjects (Wickens et al. Reference Wickens, Born and Allen1963; Wickens, Reference Wickens1970). The performance declines progressively, with interference build-up, across the first four lists (L1 to L4) and almost returns to initial level due to interference release on the fifth list (L5). This demonstrates that the patients correctly perform the task, although at a lower level than that expected from healthy subjects (maximum, around 90%; minimum, around 30%; from Wickens et al. Reference Wickens, Born and Allen1963; Wickens, Reference Wickens1970).

Fig. 1. Percentage correct recall as a function of list trials L1 to L5.

The results of the stepwise regression are presented on Table 3. The analysis showed that DISORG is predicted by flexibility [W-IR: F(1, 94)=4.61, p=0.03). This predictor is no longer present in the consecutive partial regression controlling for BIZ-DEL, which uncovered an association between DISORG and inhibition [W-IN: F(1, 52)=14.6; p<0.0005]. Similarly, the association between flexibility and DISORG was not present in the analysis controlling for AUD-HAL, which uncovered two predictors [F(2, 53)=9.94, p<0.0005]: inhibition (W-IN) and a marginally significant contribution of interference sensitivity (W-IB).

Table 3. Results of the regression analyses

DISORG, Disorganization; BIZ-DEL, bizarre delusions; AUD-HAL, auditory hallucinations; DIM-EX, diminished expression; CDSS, Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia; W-IB, interference sensitivity; W-IR, flexibility; W-IN, inhibition.

Analysis of BIZ-DEL revealed no significant predictors. This result was not modified in partial regressions controlling for AUD-HAL, antipsychotic dose and depression, but a marginal contribution of inhibition (W-IN) emerged when controlling for DISORG [F(1, 65)=6.04, p=0.02].

The regression on AUD-HAL showed a negative relationship with interference sensitivity [W-IB: F(1, 94)=6.16, p=0.02]. This association remains present in the partial regressions and is even stronger when controlling for DISORG [F(1, 65)=18.02, p<0.0005] and antipsychotic dose [chlorpromazine (CPZ): F(1, 65)=7.96, p=0.006].

Finally, a regression was performed to assess whether the DIM-EX symptoms were related to executive dysfunction. The result showed a negative association between this dimension and interference sensitivity [W-IB: F(1, 94)=4.77, p=0.03].

Discussion

The results first showed a strong relationship between AUD-HAL and interference sensitivity (W-IB). Indeed, this association was consistently observed, it persisted on partial regressions and was even stronger when controlling for DISORG. This relationship between an exaggerated sensitivity to interfering information and hallucinations emphasizes the monitoring difficulties thought to underlie the expression of these symptoms (Frith, Reference Frith1979, Reference Frith1992; Hemsley, Reference Hemsley1993). It is also reminiscent of the view that hallucinations reflect the cognitive ‘dissonance’ that arises when intrusive thoughts (i.e. DISORG) are incompatible or interfere with the individual's beliefs (i.e. delusions) (Morrison et al. Reference Morrison, Haddock and Tarrier1995).

Interference sensitivity was also significantly associated with DISORG, but this relationship was relatively weak compared with that with AUD-HAL. DISORG was also associated with decreased cognitive flexibility (W-IR). However, the partial regression indicated that this association is accounted for by BIZ-DEL, thus suggesting that these symptoms are somehow involved in the relationship between flexibility and DISORG. In fact, in another study, a direct correlation was found between delusions and measures of flexibility (i.e. color-word score of the Stroop test) (Guillem Reference Guillem, Ganeva, Pampoulova and Stip2005a), and as mentioned in the Introduction, recent cognitive accounts of delusions involve a lack of flexibility (Magaro, Reference Magaro1980; Garety et al. Reference Garety, Fowler, Kuipers, Freeman, Dunn, Bebbington, Hadley and Jones1997, Reference Garety, Kuipers, Fowler, Freeman and Bebbington2001). Nevertheless, as in several studies (Malla et al. Reference Malla, Norman, Morrison-Stewart, Williamson, Helmes and Cortese2001; Cameron, Reference Cameron, Oram, Geffen, Kavanagh, McGrath and Geffen2002; Lucas et al. Reference Lucas, Fitzgerald, Redoblado-Hodge, Anderson, Sanbrook, Harris and Brennan2004), no direct correlation was observed between delusions and executive functions. The actual relationships certainly need further exploration and likely other factors such as dysphoria (i.e. anxiety and depression) may play a role in these inconsistencies.

In fact, decreased flexibility has been identified as a main characteristic of depression (Fossatti et al. Reference Fossatti, Ergis and Allilaire2001) and, as in other studies, the present results showed a positive relationship between delusions, and dysphoria, i.e. depression and/or anxiety symptoms (Norman & Malla, Reference Norman and Malla1994; Lysaker et al. Reference Lysaker and Bell1995; Guillem et al. Reference Guillem, Pampoulova, Stip, Lalonde and Todorov2005b). Further, delusions have been considered as a ‘defense’ or ‘self-enhancing’ mechanism to counterbalance low self-esteem associated with depression (Bentall, Reference Bentall, David and Cutting1994). This also appears consistent with the recent report of interactions between delusions and a lack of cognitive flexibility (e.g. set shifting or WCST) in relation with dysphoria (i.e. social anxiety) (Lysaker & Hemmersley, Reference Lysaker and Hemmersley2006).

BIZ-DEL were also associated with a lack of inhibition (W-IN) when controlling for DISORG. This relationship, however, is relatively weak and, as reported in numerous studies, the lack of inhibition seems to be more strongly related to DISORG (Baxter & Liddle, Reference Baxter and Liddle1998; Cameron et al. Reference Cameron, Oram, Geffen, Kavanagh, McGrath and Geffen2002; Guillem et al. Reference Guillem, Ganeva, Pampoulova and Stip2005a; Leeson et al. Reference Leeson, Simpson, McKenna and Laws2005). The present results showed a similar association, but only when controlling for BIZ-DEL and AUD-HAL. The fact that the association was masked by the other positive symptoms is in keeping with early conceptions of schizophrenia in which delusions and hallucinations were considered as compensatory mechanisms against the decreased control of thought that leads to intrusions and disorganization symptoms (Bleuler, Reference Bleuler1911; Ey, Reference Ey1996).

Finally, an association was demonstrated between interference sensitivity and DIM-EX. It was, however, relatively weak and since there was no correlation between this dimension and the positive symptom dimensions, it is likely that the relationship is indirect or, at least, that it had no effect on those described above. There was also a positive association between the dose of antipsychotic medication (CPZ) and both BIZ-DEL and AUD-HAL. This relationship can be easily understood as reflecting the usual therapeutic strategy that consists of prescribing higher doses in patients with higher levels of positive symptoms. In any event, this association did not appear to have a significant effect on the results.

In summary, the results of this study generally fitted our hypotheses concerning the relationships between specific aspects of positive symptomatology and discrete processes involved in executive functions. However, as illustrated in Fig. 2, it appears that the relationships are more complex than expected. This further points to the fact (i) that the global measures usually employed are not appropriate to reveal such relationships and (ii) that it is necessary to take the interactions between symptoms, and possibly with other factors (e.g. dysphoria), into account. This type of multi-dimensional approach will certainly help better understand how cognitive mechanisms are involved in symptom expression and their impact on the patients' functional outcome.

Fig. 2. Schematic representation of the results of the regression analyses. W-IR, Wickens flexibility; W-IN, Wickens inhibition; CPZ, chlorpromazine; W-IB, Wickens interference build-up; –––, correlation; –●–, masking effect.

Appendix 1. Item composition of the symptom dimensions (Toomey et al. Reference Toomey, Kremen, Simpson, Samson, Seidman, Lyons, Faraone and Tsuang1997)

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR-MOP-49530) and the Fonds de Recherche en Santé du Québec (FRSQ-Chercheur boursier-3353). We are particularly grateful to the personnel of the out-patient clinics associated with L-H Lafontaine for helpful assistance in patient's approach and recruitment.

Declaration of Interest

None.