Introduction

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) are distinct neurodevelopmental conditions. ADHD is characterized by age-inappropriate symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity, whereas ASD is characterized by difficulties in social interaction/communication and stereotypical repetitive behavior [American Psychiatric Association (APA), 2013]. The estimated prevalence of ADHD (5–7%) is higher than ASD (1–2%) worldwide (Elsabbagh et al., Reference Elsabbagh, Divan, Koh, Kim, Kauchali, Marcín and Fombonne2012; Polanczyk, Willcutt, Salum, Kieling, & Rohde, Reference Polanczyk, Willcutt, Salum, Kieling and Rohde2014). In both disorders, brain structural abnormalities have been observed in frontal, temporal, parietal and striato-thalamic networks (Ecker, Reference Ecker2017; Norman et al., Reference Norman, Carlisi, Lukito, Hart, Mataix-Cols, Radua and Rubia2016), although the extent of their overlap is poorly understood. Furthermore, both disorders are associated with cognitive control deficits (Craig et al., Reference Craig, Margari, Legrottaglie, Palumbi, de Giambattista and Margari2016), although ASD relative to ADHD seem less severely impaired (see meta-analyses, Lipszyc & Schachar, Reference Lipszyc and Schachar2010; Willcutt, Sonuga-Barke, Nigg, & Sergeant, Reference Willcutt, Sonuga-Barke, Nigg, Sergeant, Banaschewski and Rohde2008) and display more heterogeneous performance (Geurts, van den Bergh, & Ruzzano, Reference Geurts, van den Bergh and Ruzzano2014; Kuiper, Verhoeven, & Geurts, Reference Kuiper, Verhoeven and Geurts2016). Exploring abnormalities in brain structure and cognitive control function could help elucidate the disorder-differentiating and shared difficulties in ASD and ADHD.

In ADHD, brain abnormalities are thought to represent delayed maturation in brain structure and function mediating late-developing cognitive functions such as cognitive control (Hoogman et al., Reference Hoogman, Bralten, Hibar, Mennes, Zwiers, Schweren and Franke2017; Shaw et al., Reference Shaw, Eckstrand, Sharp, Blumenthal, Lerch, Greenstein and Rapoport2007; Sripada, Kessler, & Angstadt, Reference Sripada, Kessler and Angstadt2014). Correspondingly, previous voxel-based morphometry (VBM) meta-analyses have revealed reduced gray matter volume (GMV) in ventromedial orbitofrontal cortex (vmOFC) and basal ganglia (BG) (Frodl & Skokauskas, Reference Frodl and Skokauskas2012; Nakao, Radua, Rubia, & Mataix-Cols, Reference Nakao, Radua, Rubia and Mataix-Cols2011; Norman et al., Reference Norman, Carlisi, Lukito, Hart, Mataix-Cols, Radua and Rubia2016). In addition, mega-analytic studies by the ENIGMA consortium of subcortical and cortical structure involving over 1700 and 2200 individuals with ADHD, respectively, found reduced GMV in BG, amygdala and hippocampus (Hoogman et al., Reference Hoogman, Bralten, Hibar, Mennes, Zwiers, Schweren and Franke2017), as well as reduced cortical surface areas and thickness in several frontal, temporal and parietal regions (Hoogman et al., Reference Hoogman, Muetzel, Guimaraes, Shumskaya, Mennes, Zwiers and Franke2019).

Converging with these findings are meta-analytic reports of underactivation in lateral and medial fronto-striatal networks in ADHD relative to controls during cognitive control such as in right inferior frontal gyrus (IFG)/anterior insula (AI), supplementary motor area (SMA)/anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), and the striatum (Hart, Radua, Nakao, Mataix-Cols, & Rubia, Reference Hart, Radua, Nakao, Mataix-Cols and Rubia2013; McCarthy, Skokauskas, & Frodl, Reference McCarthy, Skokauskas and Frodl2014; Norman et al., Reference Norman, Carlisi, Lukito, Hart, Mataix-Cols, Radua and Rubia2016). The role of right IFG as a potential biomarker of ADHD in particular has been discussed in several studies and a meta-analysis showing disorder-specificity of underactivation in right and/or left IFG during cognitive control in ADHD children relative to pediatric bipolar disorder (Passarotti, Sweeney, & Pavuluri, Reference Passarotti, Sweeney and Pavuluri2010), obsessive-compulsive disorder (Norman et al., Reference Norman, Carlisi, Lukito, Hart, Mataix-Cols, Radua and Rubia2016) and conduct disorder (Rubia, Reference Rubia2018; Rubia et al., Reference Rubia, Halari, Cubillo, Mohammad, Scott and Brammer2010b).

In ASD, findings from neuroimaging, post-mortem and head circumference development studies have led to the ‘early brain overgrowth theory’ (Courchesne, Campbell, & Solso, Reference Courchesne, Campbell and Solso2011; Lange et al., Reference Lange, Travers, Bigler, Prigge, Froehlich, Nielsen and Lainhart2015; Redcay & Courchesne, Reference Redcay and Courchesne2005; Schumann et al., Reference Schumann, Bloss, Barnes, Wideman, Carper, Akshoomoff and Courchesne2010), which, however, has been contested in recent studies (Ecker, Schmeisser, Loth, & Murphy, Reference Ecker, Schmeisser, Loth and Murphy2017; Raznahan et al., Reference Raznahan, Wallace, Antezana, Greenstein, Lenroot, Thurm and Giedd2013). Meta-analytic and mega-analytic findings have varied but GMV reduction in the striatum and amygdala/hippocampus was among the more frequently reported (Cauda et al., Reference Cauda, Geda, Sacco, D'Agata, Duca, Geminiani and Keller2011; DeRamus & Kana, Reference DeRamus and Kana2015; Nickl-Jockschat et al., Reference Nickl-Jockschat, Habel, Michel, Manning, Laird, Fox and Eickhoff2012; van Rooij et al., Reference van Rooij, Anagnostou, Arango, Auzias, Behrmann, Busatto and Buitelaar2018; Via, Radua, Cardoner, Happe, & Mataix-Cols, Reference Via, Radua, Cardoner, Happe and Mataix-Cols2011). Another recent meta-analysis of VBM studies in over 900 ASD patients, however, primarily found cortical abnormalities such as GMV decrease in medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) and posterior insula; and increase in left anterior temporal, right inferior temporo-parietal, left dorsolateral prefrontal (dlPFC) and precentral cortices (Carlisi et al., Reference Carlisi, Norman, Lukito, Radua, Mataix-Cols and Rubia2017). Furthermore, the ENIGMA mega-analysis has found cortical thickness increase in frontal and decrease in temporal areas (van Rooij et al., Reference van Rooij, Anagnostou, Arango, Auzias, Behrmann, Busatto and Buitelaar2018).

The whole-brain meta-analysis of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies of cognitive control in ASD (Carlisi et al., Reference Carlisi, Norman, Lukito, Radua, Mataix-Cols and Rubia2017) has found underactivation in salience and executive network areas such as mPFC, left dorsolateral and right ventrolateral prefrontal cortices (vlPFC)/AI, left cerebellum, inferior parietal lobe (IPL) and right premotor area; and overactivation in right temporo-parietal regions including default mode network (DMN) areas.

While these meta-analytic findings suggest partially overlapping brain abnormalities in ASD and ADHD, only direct comparisons can elucidate their differences and commonalities. Among such studies, a VBM study showed reduced GMV in ADHD relative to ASD in right posterior cerebellum and ASD-differentiating reduced left middle/superior temporal gyri (M/STG) (Lim et al., Reference Lim, Chantiluke, Cubillo, Smith, Simmons, Mehta and Rubia2015). Furthermore, fMRI studies have shown ASD-differentiating mPFC underactivation during reward reversal (Chantiluke et al., Reference Chantiluke, Barrett, Giampietro, Brammer, Simmons, Murphy and Rubia2015a), shared dlPFC underactivation during sustained attention and working memory (Chantiluke et al., Reference Chantiluke, Barrett, Giampietro, Brammer, Simmons and Rubia2015b; Christakou et al., Reference Christakou, Murphy, Chantiluke, Cubillo, Smith, Giampietro and Rubia2013); and shared precuneus abnormalities during sustained attention, reward reversal and the resting state (Chantiluke et al., Reference Chantiluke, Barrett, Giampietro, Brammer, Simmons, Murphy and Rubia2015a; Christakou et al., Reference Christakou, Murphy, Chantiluke, Cubillo, Smith, Giampietro and Rubia2013; Di Martino et al., Reference Di Martino, Zuo, Kelly, Grzadzinski, Mennes, Schvarcz and Milham2013). Importantly, during successful motor inhibition, ADHD-differentiating underactivation was observed in left vlPFC and BG and ASD-differentiating overactivation in bilateral IFG (Chantiluke et al., Reference Chantiluke, Barrett, Giampietro, Santosh, Brammer, Simmons and Rubia2015c). Few imaging studies, however, have directly compared the two disorders and their relatively small sample sizes have limited statistical power.

We therefore conducted meta-analyses of structural and functional abnormalities related to functions that are commonly impaired in ASD and ADHD, i.e. cognitive control. The aim of the study was to establish the most consistently disorder-differentiating and shared structural and functional deficits, which is important for developing disorder-specific or transdiagnostic treatment. Guided by previous comparative studies and meta-analyses in ASD and/or ADHD, we hypothesized that these disorders are characterized by both shared abnormalities in salience, cognitive control and DMNs as well as disorder-differentiating impairments. Structurally, we hypothesized ADHD-differentiating reduced GMV in BG/insula relative to ASD (Lim et al., Reference Lim, Chantiluke, Cubillo, Smith, Simmons, Mehta and Rubia2015; Norman et al., Reference Norman, Carlisi, Lukito, Hart, Mataix-Cols, Radua and Rubia2016), and ASD-differentiating increased GMV in frontal and temporo-parietal regions (Carlisi et al., Reference Carlisi, Norman, Lukito, Radua, Mataix-Cols and Rubia2017; Lim et al., Reference Lim, Chantiluke, Cubillo, Smith, Simmons, Mehta and Rubia2015). During cognitive control, we expected ADHD-differentiating reduced activation in right IFG and BG relative to ASD (Chantiluke et al., Reference Chantiluke, Barrett, Giampietro, Santosh, Brammer, Simmons and Rubia2015c; Norman et al., Reference Norman, Carlisi, Lukito, Hart, Mataix-Cols, Radua and Rubia2016; Passarotti et al., Reference Passarotti, Sweeney and Pavuluri2010; Rubia et al., Reference Rubia, Halari, Smith, Mohammad, Scott and Brammer2009), ASD-differentiating underactivation relative to ADHD in the medial frontal part of the cognitive control network (Carlisi et al., Reference Carlisi, Norman, Lukito, Radua, Mataix-Cols and Rubia2017; Chantiluke et al., Reference Chantiluke, Barrett, Giampietro, Brammer, Simmons, Murphy and Rubia2015a) and shared abnormal overactivation in precuneus in both disorders (Chantiluke et al., Reference Chantiluke, Barrett, Giampietro, Brammer, Simmons, Murphy and Rubia2015a; Christakou et al., Reference Christakou, Murphy, Chantiluke, Cubillo, Smith, Giampietro and Rubia2013; Di Martino et al., Reference Di Martino, Zuo, Kelly, Grzadzinski, Mennes, Schvarcz and Milham2013).

Methods

Publication search and study inclusion

Systematic literature search was conducted for peer-reviewed English language publications in PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science and ScienceDirect until 30th November 2018, for whole-brain fMRI or VBM studies in ASD and ADHD. Manual search was conducted in reference lists of previous meta-analyses. Included studies compared the ASD or ADHD groups against typically developing (TD) controls on GMV or on cognitive-control fMRI blood oxygen level dependent signal from stop-signal, go/no-go, switch, Stroop, Simon and flanker, using predefined inhibitory contrasts (online Supplement 1). Only whole-brain neuroimaging data were included, to prevent bias toward specific neuroanatomy (Friston, Rotshtein, Geng, Sterzer, & Henson, Reference Friston, Rotshtein, Geng, Sterzer and Henson2006). Excluded studies used region of interest (ROI) approaches or involved <10 patients, which were deemed lacking in statistical power (Desmond & Glover, Reference Desmond and Glover2002; Nakao et al., Reference Nakao, Radua, Rubia and Mataix-Cols2011; Thirion et al., Reference Thirion, Pinel, Mériaux, Roche, Dehaene and Poline2007). Studies that potentially report duplicate data from other publications (including mega-analyses), have no TD controls, or have provided no peak coordinates, were excluded. When samples overlapped, the largest sample was included. Mean age, proportion of males, mean IQ, cognitive control tasks, current and lifetime psychostimulant use (i.e. proportion of participants being prescribed the medication) and effect size and coordinate location of peaks for regional GMV and activation differences were extracted from each study and authors were contacted for missing information. Reports of exclusion or inclusion of people with co-occurring ASD or ADHD in the counterpart disorder groups were also extracted from the literature. Data were extracted from all studies by SL, 64% of which were also extracted by LN and CC who achieved 100% agreement. This meta-analysis was not pre-registered in a time-stamped, institutional registry prior to the research being conducted.

Meta-analyses

The anisotropic seed-based d Mapping (AES-SDM) meta-analytic software (www.sdmproject.com; online Supplement 1) employed in previous meta-analyses of ASD and ADHD (Carlisi et al., Reference Carlisi, Norman, Lukito, Radua, Mataix-Cols and Rubia2017; Frodl & Skokauskas, Reference Frodl and Skokauskas2012; McCarthy et al., Reference McCarthy, Skokauskas and Frodl2014; Norman et al., Reference Norman, Carlisi, Lukito, Hart, Mataix-Cols, Radua and Rubia2016) was used for the present voxel-wise meta-analyses. The software can accommodate statistical parametric maps or peak coordinates and effect sizes (t-scores) data. For the latter, AES-SDM computes signed (positive/negative) effect sizes and variance maps of brain regional differences between clinical and control groups by convolving an anisotropic non-normalized Gaussian kernel with Hedges effect size of each peak. Voxels correlated with the peak values are assigned higher effect sizes. Maps are then combined across studies based on random-effect model, accounting for sample size, within-study variability and between-study heterogeneity. Correlated datasets (e.g. when the same group of participants completed several cognitive tasks) were included in the meta-analysis as a single set (Norman et al., Reference Norman, Carlisi, Lukito, Hart, Mataix-Cols, Radua and Rubia2016), adjusted for shared variance of brain activation or structure across datasets. The Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines were followed (Stroup et al., Reference Stroup, Berlin, Morton, Olkin, Williamson, Rennie and Thacker2000).

Age, sex and IQ were compared across patient and control groups prior to meta-analyses in STATA14 (StataCorp, 2015), using sample-size weighted F statistics. First, VBM meta-analyses were conducted in each disorder relative to TD controls and then between the two disorders. Second, equivalent fMRI meta-analyses were conducted to examine the neural impairments observed during cognitive control within and between disorders using all available data. To explore specific cognitive-control subconstructs (e.g. Bari and Robbins, Reference Bari and Robbins2013), we conducted fMRI sub-meta-analyses of prepotent motor response inhibition, including studies employing the go/no-go and stop-signal tasks only. No other cognitive control subconstructs were explored due to insufficient data. To find the most consistent disorder-differentiating neural abnormalities regardless of demographic characteristics, we conducted sensitivity meta-analyses in an age-, sex- and IQ-matched subgroup, instead of covarying group differences in these variables that could result in false positives (Dennis et al., Reference Dennis, Francis, Cirino, Schachar, Barnes and Fletcher2009; Miller & Chapman, Reference Miller and Chapman2001). An iterative algorithm computed group differences in age, sex and IQ for all possible combinations of studies, selecting the largest subgroups with statistically nonsignificant group differences in the three variables (Carlisi et al., Reference Carlisi, Norman, Lukito, Radua, Mataix-Cols and Rubia2017). Findings surviving the sensitivity analyses in the matched subgroups are the only ones reported and discussed.

Furthermore, conjunction analyses were used to asses overlapping fMRI and GMV abnormalities within and across disorders (using threshold p < 0.005). To assess consistency of findings across age groups, supplementary age-stratified sub-meta-analyses were conducted in overall pediatric or adult age groups and in their respective age-, sex- and IQ-matched subgroups, where possible (online Supplements 3 and 4). These were complemented with a series of sample-size weighted correlational analyses between the mean sample age and extracted effect sizes of brain abnormalities averaged over 10-mm radius spheres centered at the peaks of disorder-differentiating or shared abnormalities, applying Bonferroni multiple comparison correction (online Supplement 5). Non-parametric correlations were chosen due to the bimodal distribution of age among studies. Following previous meta-analyses (Hart et al., Reference Hart, Radua, Nakao, Mataix-Cols and Rubia2013; Norman et al., Reference Norman, Carlisi, Lukito, Hart, Mataix-Cols, Radua and Rubia2016), psychostimulant effects were explored in separate meta-regressions between brain structure/function and lifetime psychostimulant exposure, i.e. proportions of samples who have ever been exposed to psychostimulants, or current psychostimulant exposure, in brain regions that are found impaired in ADHD (online Supplement 6). Supplementary meta-analyses covarying for task types (motor response inhibition, cognitive interference, motor switching and combination of tasks) and behavioral task performance (impaired, unimpaired) were also conducted to assess their impacts on disorder-differentiating findings (online Supplement 7).

A statistical threshold p < 0.005 was used for all meta-analyses (Radua & Mataix-Cols, Reference Radua and Mataix-Cols2009; Radua et al., Reference Radua, Mataix-Cols, Phillips, El-Hage, Kronhaus, Cardoner and Surguladze2012b), and a reduced threshold p < 0.0005 and a cluster extent 20 voxels was used in the meta-regressions to control for false positives (Radua et al., Reference Radua, Borgwardt, Crescini, Mataix-Cols, Meyer-Lindenberg, McGuire and Fusar-Poli2012a). Egger's tests assessed potential publication bias in the disorder-differentiating and shared findings. Jack-knife sensitivity analyses examined replicability of findings through iterative whole-brain meta-analyses, leaving one dataset out at a time (online Supplement 8; Radua and Mataix-Cols, Reference Radua and Mataix-Cols2009).

Results

Search results and sample characteristics

The systematic literature search identified 140 VBM and fMRI articles of cognitive control in ASD and ADHD. Accounting for datasets of the same clinical participants and, where possible, separating data from pediatric and adult participants resulted in 86 independent VBM datasets (38 datasets including 1533 ADHD participants and 1295 controls; 48 datasets involving 1445 ASD participants and 1477 controls) and 60 independent cognitive-control fMRI datasets (42 datasets involving 1001 ADHD participants and 1004 controls; 18 datasets involving 335 ASD participants and 353 controls) (Tables 1 and 2). Groups did not differ in age in VBM, F (3,83) = 1.24, p = 0.30, and fMRI datasets, F (3,56) = 0.68, p = 0.57, but did in sex in VBM, F (3,83) = 6.03, p = 0.0009, and fMRI datasets, F (3,56) = 5.93, p = 0.0014; and in IQ in VBM, F (3,67) = 16.2, p < 0.0001) and fMRI datasets F (3,45) = 15.5, p < 0.0001. See Table 3 for demographic characteristics.

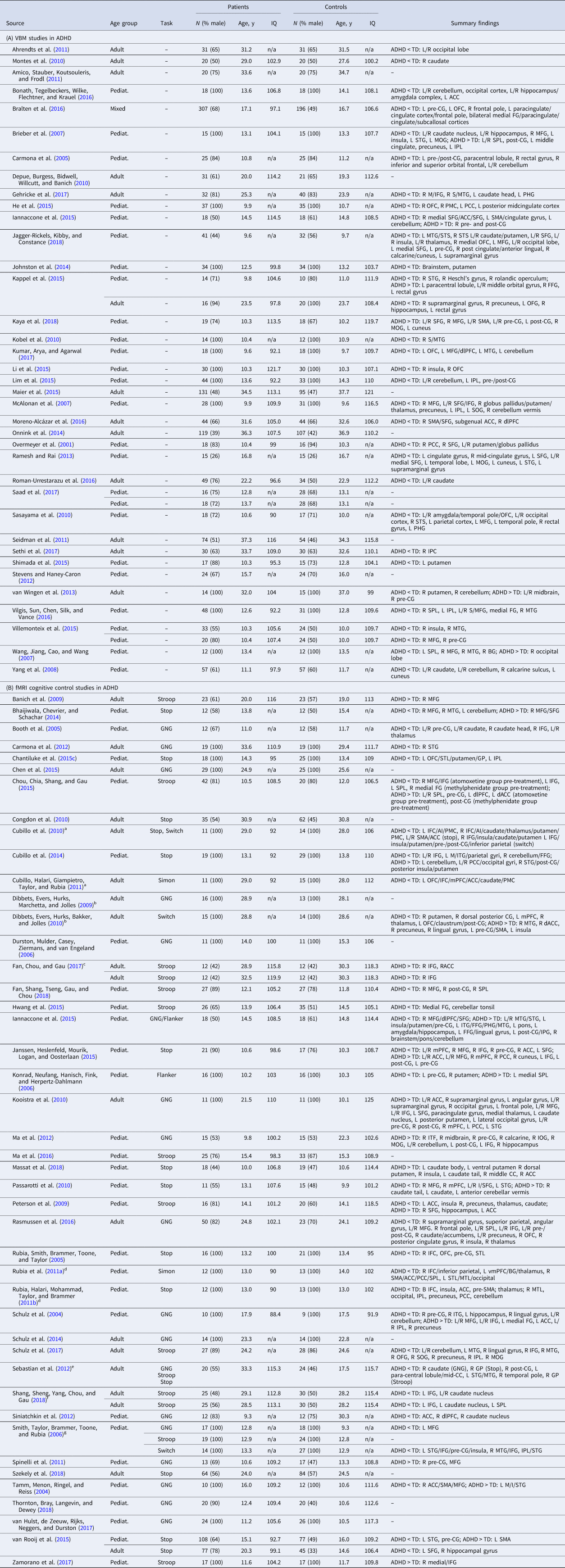

Table 1. Sample characteristics and summary findings of VBM and fMRI cognitive control studies in ADHD

N, sample size; y, years; pediat., pediatric (child/adolescent) sample; ADHD, attentional-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; TD, typically developing controls; L/R, left/right; GNG, go/no-go.

Brain regions (in alphabetical order): ACC, anterior cingulate cortex; AI, anterior insula; BG, basal ganglia; CC, cingulate cortex; dlPFC, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; dACC, dorsal ACC; FFG, fusiform gyrus; GP, globus pallidus; I/M/SFG, inferior/middle/superior frontal gyrus; I/SPL, inferior/superior parietal lobe; medial FG, medial frontal gyrus; mPFC, medial prefrontal cortex; M/STG, middle/superior temporal gyrus; OFC, orbitofrontal cortex; OFG, orbitofrontal gyrus; PCC, posterior cingulate cortex; PHG, parahippocampal gyrus; PMC, premotor cortex; pre-/post-CG, pre-/post-central gyrus; SMA, supplementary motor area; STL, superior temporal lobe; STS, superior temporal sulcus; vmPFC, ventromedial prefrontal cortex.

a–g Datasets were combined, adjusting their variance according to the method outlined in Norman et al. (Reference Norman, Carlisi, Lukito, Hart, Mataix-Cols, Radua and Rubia2016). See online Supplementary Table S2a for further information.

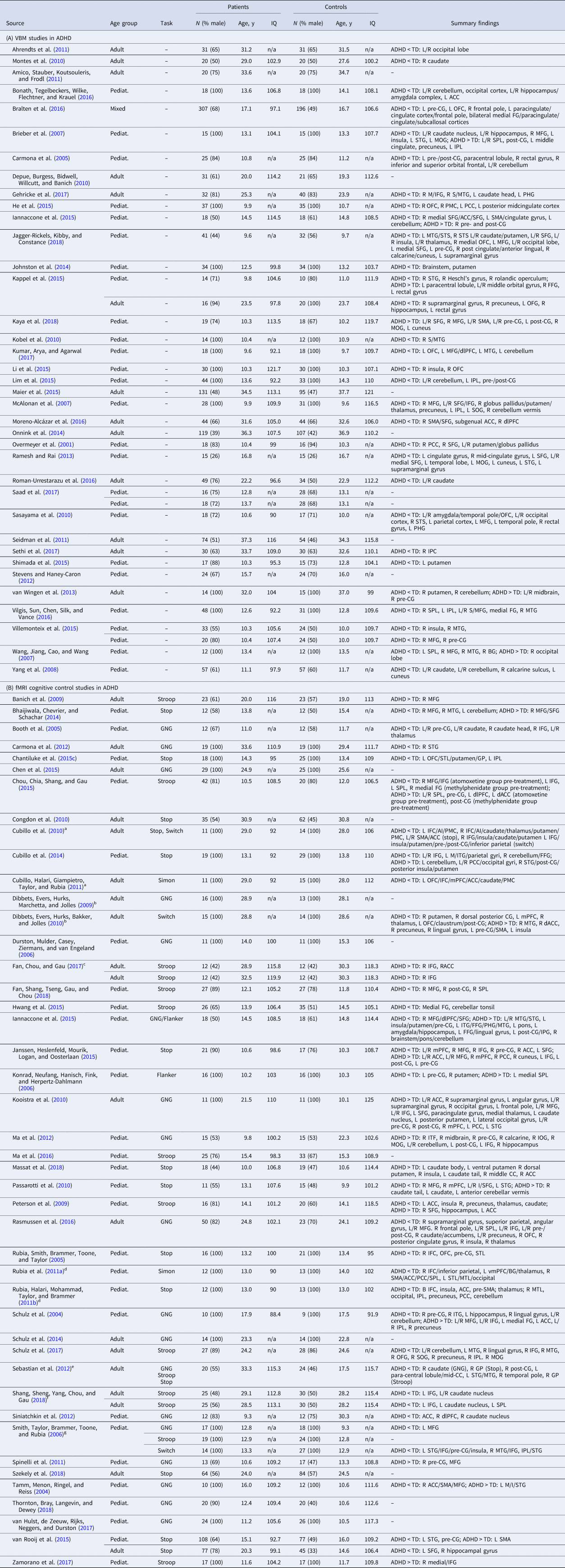

Table 2. Sample characteristics and summary findings of VBM and fMRI cognitive control studies in ASD

N, sample size; y, years; pediat., pediatric (child/adolescent) sample; ASD, autism spectrum disorder; TD, typically developing controls; L/R, left/right; GNG, go/no-go.

Brain region (in alphabetical order): ACC, anterior cingulate cortex; BG, basal ganglia; dACC, dorsal ACC; dlPFC, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; FFG, fusiform gyrus; I/M/medial/SFG, inferior/middle/medial/superior frontal gyrus; I/M/STG, inferior/middle/superior temporal gyrus; I/SPL, inferior/superior parietal lobe; mPFC, medial prefrontal cortex; OFC, orbital frontal cortex; OFG, orbital frontal gyrus; PCC, posterior cingulate cortex; pre-/post-CG, pre-/post-central gyrus; PHG, parahippocampal gyrus; PMC, premotor cortex; SMA, supplementary motor area; STS, superior temporal sulcus.

See online Supplementary Table S2b for further information.

Table 3. Characteristics of overall sample and subgroups matched on age, sex and IQ

N, overall number of subjects; TDADHD, typically developing controls in the ADHD studies; TDASD, typically developing controls in the ASD studies; VBM, voxel-based morphometry; fMRI, functional magnetic resonance imaging; % males, proportion of males among the samples; y, years; FSIQ, full scale IQ and s.d. = standard deviation.

The demographic characteristics presented here were calculated from the independent datasets with non-overlapping participants.

Disorder-differentiating and shared brain structure abnormalities

ADHD VBM

Relative to TD controls, ADHD had reduced GMV in vmOFC/vmPFC/rostral ACC (rACC), extending into right caudate, and in right putamen/posterior insula/STG, left precingulate gyrus (pre-CG), right rostrolateral PFC and left vlPFC/STG/temporal pole (Table 4A-i; Fig. 1a-i). Age-stratified analyses showed reduced GMV in right STG/putamen/posterior insula, right caudate and rACC/ventromedial PFC (vmPFC) among pediatric participants and vmOFC/subcallosal gyrus in both age groups (online Supplements 3 and 4). Current and lifetime psychostimulant exposures were associated with increased vmOFC GMV (online Supplement 6).

Fig. 1. Brain abnormalities in the ADHD and ASD groups. Abnormalities in (a) GMV and brain activations during (b) cognitive control and (c) motor response inhibition. Rows (i) and (ii) show abnormalities in ADHD and ASD relative to TD controls. Abnormalities in ADHD v. ASD, each relative to TD controls are shown in (iii) overall samples and (iv) age-, sex- and IQ-matched subgroups. In the overall sample, shared reduced rACC/mPFC GMV (MNI coordinates: 0, 46, 12; 119 voxels), and subthreshold overactivation in ADHD and underactivation in ASD in dmPFC (MNI coordinates: −2, 34, 36; 82 voxels) were observed but did not survive sensitivity analysis. A statistical threshold of p < 0.005 with a cluster extent of 20 voxels was used in all analyses.

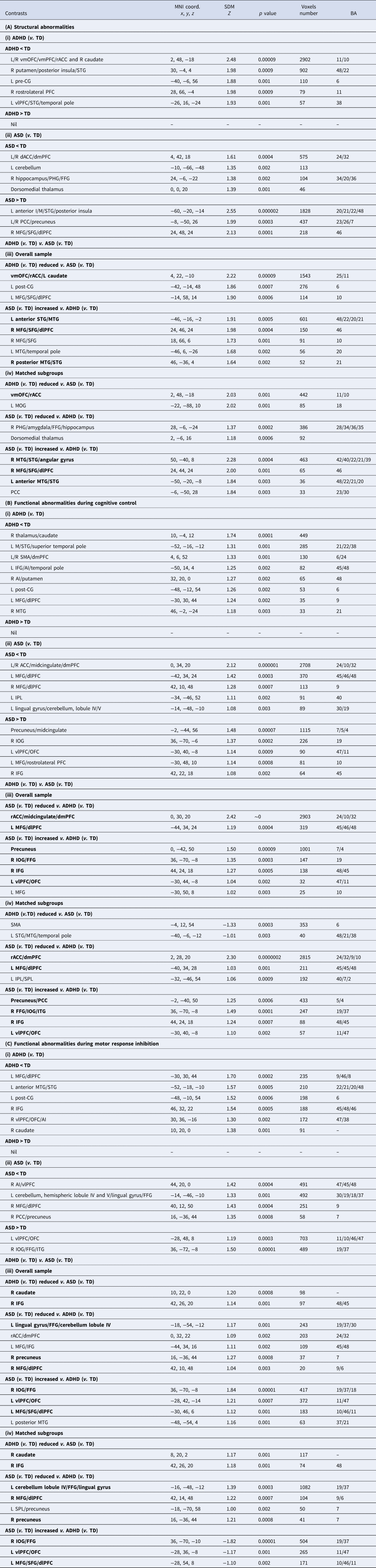

Table 4. Brain structural and functional abnormalities in ADHD relative to ASD

MNI, Montreal Neurological Institute; SDM, seed-based d mapping; BA, Brodmann area; TD, typically developing controls.

Brain regions (in alphabetical order): AI, anterior insula; dACC, dorsal anterior cingulate cortex; dlPFC, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; dmPFC, dorsomedial prefrontal cortex; FFG, fusiform gyrus; IFG, inferior frontal gyrus; I/MOG, inferior/middle occipital gyrus; I/M/STG, inferior/middle/superior temporal gyrus; I/SPL, inferior/superior parietal lobe; M/SFG, middle/superior frontal gyrus; PCC, posterior cingulate cortex; PFC, prefrontal cortex; PHG, parahippocampal gyrus; pre-CG, precentral gyrus; rACC, rostral anterior cingulate cortex; SMA, supplementary motor area; vlPFC, ventrolateral prefrontal cortex; vmOFC, ventromedial orbitofrontal cortex; vmPFC, ventromedial prefrontal cortex.

Bold prints indicate regions which survived the sensitivity analyses in subgroups matched on age, sex and IQ.

ASD VBM

Relative to TD controls, ASD had GMV reduction in dACC/dorsomedial PFC (dmPFC), left cerebellum, right hippocampus/PHG/fusiform gyrus (FFG) and dorsomedial thalamus; and enhancement in left anterior inferior/middle/superior temporal gyri (I/M/STG)/posterior insula, bilateral precuneus/posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) and right middle/superior frontal gyrus (M/SFG) (Table 4A-ii; Fig. 1a-ii). Most abnormalities in the overall sample, i.e. in left cerebellum, dorsomedial thalamus, precuneus/PCC and right MFG/SFG/dlPFC GMV were also found among pediatric participants, and enhanced left anterior STG/MTG GMV was found in both age subgroups (online Supplements 3 and 4).

ADHD v. ASD VBM

People with ADHD, relative to ASD, had consistently disorder-differentiating reduced vmOFC/rACC/left caudate GMV; while people with ASD, relative to ADHD, showed increased GMV in left anterior STG/MTG, right MFG/SFG/dlPFC, and right posterior MTG/STG (Table 4A-iii, iv; Fig. 1a-iii, iv). Reduced vmOFC GMV was most consistently ADHD-differentiating in adults, while the medial prefrontal GMV reduction in rACC/dmPFC was more apparent among pediatric participants (online Supplements 3 and 4).

Disorder-differentiating and shared brain abnormalities during cognitive control

ADHD fMRI

During cognitive control, ADHD relative to TD controls, showed underactivation in right thalamus/caudate, left MTG/STG/superior temporal pole, bilateral SMA/dmPFC, left IFG/AI/temporal pole, right AI/putamen, left postcingulate gyrus (post-CG), left MFG/dlPFC and right MTG (Table 4B-i, Fig. 1b-i). Age-stratified analyses showed underactivated dmPFC clusters and left post-CG among pediatric participants, in all regions but the dmPFC and left post-CG in adults; and in left M/STG/temporal pole in both groups (online Supplements 3 and 4). Lifetime psychostimulant exposure was positively associated with activation in left IFG (online Supplement 6).

During motor response inhibition specifically, underactivation was found in ADHD relative to TD controls in left MFG/dlPFC, left anterior MTG/STG, left post-CG, right vlPFC/OFC/AI, right IFG and right caudate (Table 4C-i, Fig. 1c-i). Age-stratified analyses showed that underactivation in left MTG/STG was apparent among pediatric participants, underactivation in left MFG/dlPFC was apparent in adults, while underactivation in right vlPFC/AI was apparent in both age groups (online Supplements 3 and 4).

ASD fMRI

During cognitive control, ASD relative to TD controls showed underactivation in ACC/midcingulate/dmPFC, left MFG/dlPFC, right MFG/dlPFC, left IPL and left lingual gyrus/cerebellum; and overactivation in left precuneus/midcingulate, right inferior occipital gyrus (IOG), left vlPFC/OFC, left MFG/rostrolateral PFC and right IFG (Table 4B-ii, Fig. 1b-ii). Underactivation in rdACC/dmPFC and left IPL; and overactivation in precuneus, left vlPFC/OFC and left MFG/dlPFC were found in adults (online Supplements 3 and 4). No pediatric sub-meta-analyses were conducted due to insufficient fMRI data.

During motor response inhibition, underactivation was found in ASD relative to TD controls in right AI/vlPFC, left cerebellum, right MFG/dlPFC and right PCC/precuneus; while overactivation was found in left vlPFC/OFC and right IOG/FFG/ITG (Table 4C-ii; Fig. 1c-ii). No age-stratified sub-meta-analyses were conducted due to insufficient data.

ADHD v. ASD fMRI

During cognitive control, ASD-differentiating underactivation was found in rACC/midcingulate/dmPFC and left MFG/dlPFC; and overactivation was found in precuneus, right IOG/FFG, right IFG and left vlPFC/OFC (Table 4B-iii, iv; Fig. 1b-iii, iv). The age-stratified analysis, which was conducted only in adults due to available data, found ASD-differentiating underactivation relative to ADHD in rdACC/dmPFC and overactivation in precuneus and left vlPFC/OFC (online Supplement 4). No ADHD-differentiating abnormalities were found.

During motor response inhibition, ADHD-differentiating underactivation was found in right caudate and IFG. Furthermore, ASD-differentiating underactivation was found in left lingual gyrus/FFG/cerebellum, right precuneus and right MFG/dlPFC; while overactivation was found in right IOG/FFG, left vlPFC/OFC and left MFG/SFG/dlPFC (Table 4C-iii, iv; Fig. 1c-iii, iv). Underactivation in right AI (MNI coordinates: 40, 20, −6; 51 voxels) was shared between disorders.

Multimodal VBM and fMRI analyses

In ADHD relative to TD controls, overlapping reduced GMV and fMRI underactivation was found during cognitive control in right caudate nucleus (MNI coordinates: 10, 10, 8; 194 voxels). In ASD relative to TD controls, reduced GMV and fMRI underactivation was found in dACC/mPFC (MNI coordinates: 0, 40, 16; 575 voxels).

Controlling for task type and performance in fMRI meta-analysis

The disorder-differentiating impairment during cognitive control was unchanged after covarying for task types and performance. During motor response inhibition, ADHD-differentiating underactivation in right IFG and caudate did not survive covarying for task performance (online Supplement 7).

Publication bias and jack-knife reliability findings

Egger tests suggest no significant publication bias for the structural, ts(84) = 0.32–2.29, ps ⩾ 0.1, and functional abnormalities during cognitive control, ts(58) = 0.04–1.90, ps ⩾ 0.38, and during motor response inhibition specifically, ts(40) = 0.41–1.37, ps ⩾ 0.99 (Bonferroni adjusted p values). Jack-knife reliability analyses suggest robust disorder-differentiating findings (online Supplement 8).

Discussion

We aimed at elucidating the most consistent disorder-differentiating and shared brain abnormalities in ASD and ADHD. The findings revealed predominantly disorder-differentiating abnormalities, particularly striking in the VBM meta-analysis, where we found ADHD-differentiating reduced GMV in vmOFC; and ASD-differentiating increased GMV in bilateral temporal and right lateral prefrontal cortices. In fMRI, the findings overall showed predominantly ASD-differentiating abnormalities, including underactivation in medial frontal and overactivation in bilateral ventrolateral regions and precuneus during cognitive control. During motor response inhibition specifically, ADHD-differentiating underactivation was in right IFG and caudate, while ASD had differentiating underactivation mostly in posterior regions, and overactivation in left dorsal and ventral frontal regions (Fig. 2). Both disorders shared underactivation in right AI. The findings overall suggest that people with ADHD and ASD have mostly distinct brain abnormalities.

Fig. 2. Summary of consistent disorder-differentiating and shared brain abnormalities in ADHD and ASD. Findings of (a) GMV abnormalities and brain activation abnormalities during (b) cognitive control and (c) motor response inhibition. A statistical threshold of p < 0.005 with a cluster extent of 20 voxels was used in all analyses.

The ADHD-differentiating decreased GMV in vmOFC relative to ASD may be related to common reports of reward-based decision-making neural network dysfunctions in ADHD (e.g. Chantiluke et al. Reference Chantiluke, Christakou, Murphy, Giampietro, Daly, Ecker and Rubia2014; Cubillo, Halari, Smith, Taylor, & Rubia, Reference Cubillo, Halari, Smith, Taylor and Rubia2012; Rubia, Reference Rubia2018; Tegelbeckers et al. Reference Tegelbeckers, Kanowski, Krauel, Haynes, Breitling, Flechtner and Kahnt2018), and supports the hypothesis of distinctive reward processing in ASD and ADHD (Kohls et al., Reference Kohls, Thönessen, Bartley, Grossheinrich, Fink, Herpertz-Dahlmann and Konrad2014; van Dongen et al., Reference van Dongen, von Rhein, O'Dwyer, Franke, Hartman, Heslenfeld and Buitelaar2015). Reduced vmOFC GMV in ADHD compared to TD controls extends relatively recent meta-analytic findings (McGrath & Stoodley, Reference McGrath and Stoodley2019; Norman et al., Reference Norman, Carlisi, Lukito, Hart, Mataix-Cols, Radua and Rubia2016), and there have been correlational reports between OFC GMV reduction and increased ADHD symptoms in large-scale general population studies (Albaugh et al., Reference Albaugh, Orr, Chaarani, Althoff, Allgaier, D'Alberto and Potter2017; Fuentes et al., Reference Fuentes, Barros-Loscertales, Bustamante, Rosell, Costumero and Avila2012; Korponay et al., Reference Korponay, Dentico, Kral, Ly, Kruis, Goldman and Davidson2017). Interestingly, our age-stratified results suggest that the ADHD-differentiating deficit features more consistently in adulthood, when co-occurring addiction behavioral problems increase (e.g. Breyer et al. Reference Breyer, Botzet, Winters, Stinchfield, August and Realmuto2009; Ortal et al. Reference Ortal, van de Glind, Johan, Itai, Nir, Iliyan and van den Brink2015), more so in ADHD than in ASD (e.g. Sizoo et al. Reference Sizoo, van den Brink, Koeter, Gorissen van Eenige, van Wijngaarden-Cremers and van der Gaag2010; Solberg et al. Reference Solberg, Zayats, Posserud, Halmoy, Engeland, Haavik and Klungsoyr2019).

The increased left anterior and right posterior temporal GMV in ASD is a consistent VBM meta-analytic finding in ASD relative to TD controls (Carlisi et al., Reference Carlisi, Norman, Lukito, Radua, Mataix-Cols and Rubia2017; Cauda et al., Reference Cauda, Geda, Sacco, D'Agata, Duca, Geminiani and Keller2011; DeRamus & Kana, Reference DeRamus and Kana2015; Duerden, Mak-Fan, Taylor, & Roberts, Reference Duerden, Mak-Fan, Taylor and Roberts2012). Enhanced left anterior GMV was the only mega-analytic impairment finding in over 400 people with ASD but it did not survive in smaller age- and sex-matched subgroups (Riddle, Cascio, & Woodward, Reference Riddle, Cascio and Woodward2017). Our meta-analysis may have increased statistical power to detect the differences. The ASD-differentiating increased left temporal GMV extends findings from a small VBM ASD/ADHD comparative study (Lim et al., Reference Lim, Chantiluke, Cubillo, Smith, Simmons, Mehta and Rubia2015). The left temporal lobe plays roles in semantic and language processing (Binder et al., Reference Binder, Gross, Allendorfer, Bonilha, Chapin, Edwards and Weaver2011), while the right posterior temporoparietal cortices play a role in social interaction and mentalizing, i.e. the ability to attribute mental states in others (Krall et al., Reference Krall, Rottschy, Oberwelland, Bzdok, Fox, Eickhoff and Konrad2015). These structures are important for social cognition, which have been thought to be an ASD-specific impairment (Kana et al., Reference Kana, Maximo, Williams, Keller, Schipul, Cherkassky and Just2015; Lombardo, Chakrabarti, Bullmore, & Baron-Cohen, Reference Lombardo, Chakrabarti, Bullmore and Baron-Cohen2011; White, Frith, Rellecke, Al-Noor, & Gilbert, Reference White, Frith, Rellecke, Al-Noor and Gilbert2014).

The ASD-differentiating increased right dlPFC GMV has not converged in smaller meta-analyses (Carlisi et al., Reference Carlisi, Norman, Lukito, Radua, Mataix-Cols and Rubia2017; DeRamus & Kana, Reference DeRamus and Kana2015), possibly reflecting heterogeneity in findings. Right dlPFC is important for cognitive control, working memory and cognitive flexibility (Szczepanski & Knight, Reference Szczepanski and Knight2014). Neuronal and gray matter overgrowth have been reported in pediatric ASD in small ROI-based neuroimaging and post-mortem studies (Carper & Courchesne, Reference Carper and Courchesne2005; Courchesne et al., Reference Courchesne, Mouton, Calhoun, Semendeferi, Ahrens-Barbeau, Hallet and Pierce2011b; Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Reiss, Tatusko, Ikuta, Kazmerski, Botti and Kates2009), but they have not been replicated in wider age range of ASD cases with cognitive flexibility deficits (Griebling et al., Reference Griebling, Minshew, Bodner, Libove, Bansal, Konasale and Hardan2010).

The disorder-differentiating GMV increase in ASD and decrease in ADHD may possibly be related to the disorders' contrasting developmental trajectories (Courchesne et al., Reference Courchesne, Campbell and Solso2011a; Shaw et al., Reference Shaw, Eckstrand, Sharp, Blumenthal, Lerch, Greenstein and Rapoport2007). However, while most of our ADHD-differentiating findings showed reduction in structure and function that may possibly reflect delayed maturation in ADHD, the ASD-differentiating enhanced clusters were not found consistently in the pediatric sub-meta-analysis. Recent findings suggest that early brain overgrowth is not a defining characteristic of toddlers with high-risk for developing ASD (Hazlett et al., Reference Hazlett, Gu, Munsell, Kim, Styner, Wolff and Statistical2017), and may be specific to boys with regressive autism (Nordahl et al., Reference Nordahl, Lange, Li, Barnett, Lee, Buonocore and Amaral2011), who are underrepresented across studies. Thus, our findings are unlikely to reflect early brain overgrowth.

In the fMRI meta-analyses, ASD-differentiating impairments were predominant medial and left middle prefrontal underactivation and in bilateral ventrolateral prefrontal overactivation during cognitive control, while ADHD-differentiating underactivation emerged during motor inhibition in right inferior frontal and striatal regions. The ADHD-differentiating underactivation in right IFG and caudate, key regions implicated in inhibitory control (Rae, Hughes, Weaver, Anderson, & Rowe, Reference Rae, Hughes, Weaver, Anderson and Rowe2014; Zhang, Geng, & Lee, Reference Zhang, Geng and Lee2017), are consistent with previous meta-analytic findings in ADHD during cognitive control (Hart et al., Reference Hart, Radua, Nakao, Mataix-Cols and Rubia2013; McCarthy et al., Reference McCarthy, Skokauskas and Frodl2014; Norman et al., Reference Norman, Carlisi, Lukito, Hart, Mataix-Cols, Radua and Rubia2016) and extends the role of these regions, in particular right IFG, as disorder-specific neurofunctional biomarker of ADHD, as it has previously been observed relative to bipolar, obsessive compulsive and conduct disorders (Norman et al., Reference Norman, Carlisi, Lukito, Hart, Mataix-Cols, Radua and Rubia2016; Passarotti et al., Reference Passarotti, Sweeney and Pavuluri2010; Rubia, Reference Rubia2018; Rubia et al., Reference Rubia, Halari, Smith, Mohammad, Scott and Brammer2009, Reference Rubia, Cubillo, Smith, Woolley, Heyman and Brammer2010a, Reference Rubia, Halari, Cubillo, Mohammad, Scott and Brammer2010b).

The mPFC underactivation in ASD is a consistent meta-analytic finding during cognitive control and related functions (Carlisi et al., Reference Carlisi, Norman, Lukito, Radua, Mataix-Cols and Rubia2017; Di Martino et al., Reference Di Martino, Ross, Uddin, Sklar, Castellanos and Milham2009; Philip et al., Reference Philip, Dauvermann, Whalley, Baynham, Lawrie and Stanfield2012). The region is also implicated in functions such as sensory, emotion and social-processing domains typically impaired in ASD (Kana, Patriquin, Black, Channell, & Wicker, Reference Kana, Patriquin, Black, Channell and Wicker2016; Martinez-Sanchis, Reference Martinez-Sanchis2014; South & Rodgers, Reference South and Rodgers2017). Intriguingly, the mPFC underactivation was ASD-differentiating relative to ADHD. While both medial and lateral PFC are activated during motor inhibition (Rae et al., Reference Rae, Hughes, Weaver, Anderson and Rowe2014; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Geng and Lee2017), the activation of mPFC are more reliably tapped by cognitive interference tasks thus it may have closer associations with change or conflict detection (Aron, Herz, Brown, Forstmann, & Zaghloul, Reference Aron, Herz, Brown, Forstmann and Zaghloul2016). Whether our findings represent dissociated frontal brain functional impairment in ASD from ADHD in sub-constructs of cognitive control should thus be tested further meta-analytically when more fMRI findings are available.

While both disorders show functional abnormalities in PFC in both hemispheres, the ASD-differentiating atypical activation was more predominantly on the left, in contrast to the right-lateralized ADHD-differentiating fronto-striatal underactivation, although atypical brain lateralization is not uncommon finding in ASD (Dichter, Reference Dichter2012; Floris & Howells, Reference Floris and Howells2018; Kleinhans, Muller, Cohen, & Courchesne, Reference Kleinhans, Muller, Cohen and Courchesne2008). Most importantly, comparisons between each disorder relative to their respective TD controls show that neural impairment in ADHD is overwhelmingly characterized by fronto-striato-temporal underactivation, which is in line with the previous findings of a developmental lag of cognitive control networks (Sripada et al., Reference Sripada, Kessler and Angstadt2014), whereas the impairments in ASD implicate both under- and overactivation clusters in executive, attentional and, even, fronto-parieto-occipital visuo-perceptual brain regions. Of note, abnormally enhanced recruitment of posterior brain regions in ASD has been observed during working memory (Koshino et al., Reference Koshino, Carpenter, Minshew, Cherkassky, Keller and Just2005; Vogan et al., Reference Vogan, Morgan, Lee, Powell, Smith and Taylor2014), psychomotor vigilance (Christakou et al., Reference Christakou, Murphy, Chantiluke, Cubillo, Smith, Giampietro and Rubia2013; Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, Christakou, Daly, Ecker, Giampietro, Brammer and Rubia2014) and temporal discounting (Chantiluke et al., Reference Chantiluke, Christakou, Murphy, Giampietro, Daly, Ecker and Rubia2014; Norman et al., Reference Norman, Carlisi, Christakou, Chantiluke, Murphy, Simmons and Rubia2017). This thus suggests a complex pattern of neurofunctional abnormality in ASD, with compromised cortical specialization, possibly reflecting both neural impairments inherent to ASD and, possibly, ensuing neuronal compensation (see review Floris and Howells, Reference Floris and Howells2018).

The ASD-differentiating overactivation in PCC/precuneus, which was also unimpaired in ADHD relative to their respective controls, was unexpected, however. The overactivation in precuneus/PCC in ASD, which has been shown in a variety of tasks and resting-state condition (Christakou et al., Reference Christakou, Murphy, Chantiluke, Cubillo, Smith, Giampietro and Rubia2013; Kennedy, Redcay, & Courchesne, Reference Kennedy, Redcay and Courchesne2006; Murdaugh et al., Reference Murdaugh, Shinkareva, Deshpande, Wang, Pennick and Kana2012; Spencer et al., Reference Spencer, Chura, Holt, Suckling, Calder, Bullmore and Baron-Cohen2012), presumably indicates DMN dysregulation. The lack of overactivation in PCC/precuneus in ADHD during cognitive control were apparent in previous meta-analyses (McCarthy et al., Reference McCarthy, Skokauskas and Frodl2014; Norman et al., Reference Norman, Carlisi, Lukito, Hart, Mataix-Cols, Radua and Rubia2016), and could potentially be related to psychostimulant exposure which has shown to normalize DMN functioning (Liddle et al., Reference Liddle, Hollis, Batty, Groom, Totman, Liotti and Liddle2011; Peterson et al., Reference Peterson, Potenza, Wang, Zhu, Martin, Marsh and Yu2009; Rubia et al., Reference Rubia, Alegria, Cubillo, Smith, Brammer and Radua2014).

Finally, shared functional abnormality between disorders was found during motor response inhibition only in right AI, which is part of the salience network (Menon & Uddin, Reference Menon and Uddin2010). The limited shared abnormality may seem at odds with the typical observation of psychiatric comorbidities in clinical settings, but individuals with ASD and ADHD are typically selectively recruited into imaging studies, excluding specific psychiatric comorbidities, which could have emphasized the differences between disorders, at the cost of their representativeness.

On the other hand, the findings of disorder differences are more likely to be underestimated. First, typically stringent statistical corrections applied by individual studies could have concealed true group differences in coordinate-based meta-analyses. The ADHD-differentiating findings, particularly, are likely underestimated by co-occurring ADHD in the ASD groups due to past preclusion of ADHD diagnosis in ASD (APA, 2000). Studies attempting to include more representative samples of the disorders may have included comorbid ASD and ADHD cases, perhaps at higher rates in ASD than in ADHD, as shown in prevalence studies in community representative samples (Gjevik, Eldevik, Fjæran-Granum, & Sponheim, Reference Gjevik, Eldevik, Fjæran-Granum and Sponheim2011; Hollingdale, Woodhouse, Young, Fridman, & Mandy, Reference Hollingdale, Woodhouse, Young, Fridman and Mandy2019; Salazar et al., Reference Salazar, Baird, Chandler, Tseng, O'sullivan, Howlin and Simonoff2015; Simonoff et al., Reference Simonoff, Pickles, Charman, Chandler, Loucas and Baird2008). Long-term medication exposure is also likely to have masked the ADHD-differentiating findings.

Other limitations of the meta-analyses include the fewer number of participants with ASD relative to ADHD, which could have reduced power for detecting small ASD-differentiating impairments and increased the probability of false positive findings, particularly in the fMRI meta- and sub-meta-analyses. The representativeness of the meta-analytic findings may also be limited by the fact that many studies, particularly in ADHD, investigated males specifically. In ASD, the majority of studies have focused on adults and predominantly high-functioning individuals only (with a few exceptions, i.e. Cai et al. Reference Cai, Hu, Guo, Yang, Situ and Huang2018; Contarino, Bulgheroni, Annunziata, Erbetta, & Riva, Reference Contarino, Bulgheroni, Annunziata, Erbetta and Riva2016; Retico et al. Reference Retico, Giuliano, Tancredi, Cosenza, Apicella, Narzisi and Calderoni2016; Riva et al. Reference Riva, Annunziata, Contarino, Erbetta, Aquino and Bulgheroni2013; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Fu, Chen, Duan, Guo, Chen and Chen2017; Yang et al. Reference Yang, Huang, Li, Fang, Zhao, Nan and Cui2018), even though individuals with learning disability made up a significant proportion of the ASD population (e.g. Charman et al., Reference Charman, Pickles, Simonoff, Chandler, Loucas and Baird2011). Furthermore, brain-behavior correlations could not be examined due to variations of disorder trait measures across studies. Finally, the influence of task discrepancies across studies could not be fully assessed due to limited data for the non-motor cognitive control tasks.

Conclusions

These comparative meta-analyses of brain structure and function show predominantly disorder-differentiating abnormalities in the form of decreased GMV in vmOFC reward-processing regions in ADHD and increased GMV in ASD in frontal and temporal cortices, part of the central executive and social cognition networks. Disorder-differentiating fMRI deficits were predominantly observed in ASD in medial frontal executive, ventrolateral prefrontal and DMN regions when including all cognitive control tasks; and in ADHD in inferior fronto-striatal regions during motor response inhibition only. Shared functional abnormality was limited to right AI during motor response inhibition. Therefore, people with ADHD and ASD appear to have mostly distinct brain structure and cognitive-control functional abnormalities. The findings contribute to the elucidation of the differential brain abnormalities in the two disorders, which is important for the understanding of their underlying pathophysiology and could ultimately aid in the development of future, disorder-differentiated behavioral, pharmacological or neurotherapeutic treatments.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720000574.

Acknowledgement

We thank all authors of the included studies who provided additional data for this meta-analysis. We also thank Toby Wise for insightful discussions on the statistical methods used in this meta-analysis.

Financial support

SL and LN were supported by Medical Research Council and Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology, and Neuroscience (IoPPN) Ph.D. Excellence awards. CC is supported by a Wellcome Trust Sir Henry Wellcome Postdoctoral Fellowship (206459/Z/17/Z). JR receives support from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III and co-funded by European Union (ERDF/ESF, ‘Investing in your future’, Miguel Servet Research Contract CPII19/00009 and Research Project Grant PI19/00394). HH was supported by a grant from the Lila Weston Foundation for Medical Research and the Kids Company to KR. ES and KR receive research support from the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley Foundation Trust (IS-BRC-1215-20018). ES furthermore is supported by the NIHR through a program grant (RP-PG-1211-20016) and Senior Investigator Award (NF-SI-0514-10073), the European Union Innovative Medicines Initiative (EU-IMI 115300), Autistica (7237) Medical Research Council (MR/R000832/1, MR/P019293/1), the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC 003041/1) and Guy's and St Thomas' Charitable Foundation (GSTT EF1150502) and the Maudsley Charity. KR and SL are currently supported by an MRC Grant MR/P012647/1 to KR. This study is supported by funding from the UK Department of Health via the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) for Mental Health at South London and the Maudsley National Health Service (NHS) Foundation Trust and the IoPPN, King's College London, which also support both senior authors, ES and KR. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Conflict of interest

KR has received grants from Lilly and Shire pharmaceuticals and speaker's bureau from Shire, Lilly and Medice. Other authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.