Introduction

Manic-depressive insanity … includes the whole domain of so-called period and circular insanity [and] … simple mania, [and] the greatest part of the morbid states termed melancholia… In the course of the years, I have become more and more convinced that of the above mentioned states only represent manifestations of a single morbid process… We distinguish first of all manic states with the essential morbid symptoms of flight of ideas, exalted mood and pressure of activity.

[Kraepelin's Textbook, 8th edition, translated by M. Barclay, pp. 1–4. Published 1909–1915 (Kraepelin, Reference Kraepelin1921). Italics added.]

This description of one of his great nosologic constructs – manic-depressive insanity – was written toward the end of Kraepelin's clinical career. In it, he concludes that this syndrome was etiologically homogeneous. Furthermore, he understood one central form of that entity – mania – to have a simple clinical structure resting on two key signs (pressured speech and hyperactivity) and one key symptom (euphoria).

The introduction of operationalized diagnostic criteria in DSM-III in 1980 (APA, 1980; Decker, Reference Decker2013) changed our approach to psychiatric diagnosis. These criteria now form the focus of our diagnostic teaching and our clinical evaluations. Their use is often required for research funding and publication. While the benefits of operationalized criteria are widely appreciated, their widespread use has had unintended consequences (Andreasen, Reference Andreasen2007; Hyman, Reference Hyman2010; Kendler, Reference Kendler2014). Evaluations of our patients are often limited to the DSM criteria as if those were the only symptoms and signs of import. Furthermore, we often assume that our disorders are nothing more than the criteria (Hyman, Reference Hyman2010).

I have engaged in historical reviews to evaluate these concerns for major psychiatric disorders, having previously examined depression (Kendler, Reference Kendler2016a ) and schizophrenia (Kendler, Reference Kendler2016b ). Here, I study mania. As in past efforts, I have located and reviewed clinical descriptions of mania found in textbooks between ~1900 and 1960 that adopt a broadly Kraepelinian diagnostic perspective. I do this because the syndrome of mania has, over its long history, had many different formulations most of which are not directly comparable with the Kraepelinian syndrome (Berrios Reference Berrios1981, Reference Berrios2004; Healy Reference Healy2008).

I organize and present the key signs and symptoms described in these sources and rank them by frequency. Then I evaluate the relationship between them and the symptomatic criteria for mania in the major modern US diagnostic systems from Feighner (Feighner et al. Reference Feighner, Robins, Guze, Woodruff, Winokur and Munoz1972) through DSM-5 (APA, 2013). Finally, I review what can be learned from this process about the nature and optimal use of DSM criteria.

Method

I identified textbooks of Psychiatry or Psychological Medicine published from ~ 1900 to 1960 and written or translated into English from three major sources: Amazon.com, the National Library of Medicine and forgottenbooks.com. Textbooks were rejected if they did not adopt a broadly Kraepelinian perspective on mania which also required that I sample textbooks after 1900. Muncie's textbook (Muncie, Reference Muncie1939) was Meyerian in orientation but it was clear that his chapter on ‘thymergasic reactions’ was describing the manic-depressive syndrome by another name. I used 1960 as a cut-off because that would antedate the development of the first major operationalized diagnostic criteria set – the Feighner Criteria (Feighner et al. Reference Feighner, Robins, Guze, Woodruff, Winokur and Munoz1972). In addition, given the latest textbook I reviewed was published in 1957, descriptions of the mania syndrome would not be substantially influenced by the widespread use of antipsychotic and mood-stabilizing drugs (Swazey, Reference Swazey1974; Shorter, Reference Shorter2009).

As in any such review, a number of decisions were necessary. Most textbooks contained a single section providing a clinical description of the manic syndrome. Often this section would begin with a description of the early phases of the disorder, sometimes termed hypomania. Typically, then ‘mania’ or ‘simple mania’ and, sometimes, ‘acute mania’ and/or ‘chronic mania’ would be described. In this report, I took clinical descriptions from all these subsections. However, some texts included a separate description of what was alternatively termed ‘delirious’. ‘confused’ or ‘confusional’ mania. This is quite a different syndrome from the more typical manic episodes, closely resembling stage III mania described by Goodwin (Carlson & Goodwin, Reference Carlson and Goodwin1973). It was characterized by clouding of consciousness, confusion, incoherence and marked behavioral disorganization. Often restraint, and forced fluids and food were deemed necessary to prevent death. I did not include, in my review, signs and symptoms noted only in these sections as this form of mania represents a relatively distinct syndrome, symptoms of which are not well represented in the operationalized criteria for mania developed in North America.

When multiple editions were available, I examined the earliest edition available to me. In total, I reviewed 18 textbooks published from 1899 to 1956 from the USA (8), UK (7), Germany (1), Switzerland (1), and France (1). I reviewed the texts in historical order, creating categories for signs and symptoms as I progressed. After going through all the texts one time, developing and scoring the categories, I went back a second time to key texts to insure the consistent application of my approach. I created four categories on first review I then deleted because they were reported by five or fewer of the writers: (i) narcissism (self-centeredness), (ii) menstrual changes in women, (iii) hyperesthesia (sense of improved sight and hearing and increased tactile sensitivity), and (iv) reduced work ability. In Table 1, I included, when possible, short quotes from the text and typically dispensed for convenience with quotation marks and with the … spacing if I deleted words or phrases for brevity's sake.

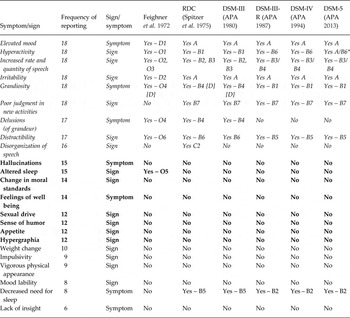

Table 1. Clinical features of mania as recorded by 18 textbook authors from ~1900 to 1960

* Signs and symptoms of mania considered by the authors to be of cardinal clinical importance.

Three further issues arose during this process. First, I never accepted symptoms or signs contained only in case reports. Second, I did not summarize the numerous comments in most texts about functions considered intact in mania such as orientation and memory. Third, eight authors, including Kraepelin, noted particular signs and symptoms of mania they considered of cardinal clinical importance. Those are identified in Table 1 by an asterisk (*).

Results

Description of findings

The results of this review are summarized in Table 1 which lists the 22 symptoms and signs of mania in the order of the frequency with which they were reported. To help organize these findings, the symptoms are divided into three groups: category A – nine symptoms/signs reported by 16 or more authors; category B – eight symptoms/signs reported by 11–15 authors; and category C – five symptoms/signs reported by 10 or fewer authors.

Category a symptoms/signs

Two symptoms (elevated mood and grandiosity) and four signs of mania (hyperactivity, pressured speech, irritability, and new activities with painful consequences) were reported by all authors. A wide range of terms were used to describe the manic mood: elated, cheerful, exalted, good humored, happy, glad, overjoyed, gay, exhilarated, boisterous, merry, high-spirited, exuberant, excited, and euphoric. The hyperactivity could range from an increased pace of typical daily tasks to poorly organized and rapidly shifting behaviors and, in more severe episodes, destructive agitation. Several authors commented on how little of practical importance was typically produced during these hyperactive episodes and the striking lack of fatigue. Pressured speech was most often described as ‘flight of ideas’ but other descriptions were used including: talkative, chatters incessantly, and logorrhea. Irritability was also noted by all authors, often with the comment that it would typically emerge when someone tried to interfere with the plans of the manic patient. Other related terms utilized included snappish, rude, angry, quarrelsome, impatient, and abusive.

Grandiose ideation was described by every author in a variety of ways including: exaggerated self-evaluation, expansive, boastful, overconfident, colossal conceit, self-expansion, and radiant self-confidence. I termed the final symptom/sign described by every author ‘poor judgment in new activities’. While described in a variety of ways, the essence of this sign was the initiation of new social, interpersonal or business activities which reflected poor judgment about the likely negative consequences. The two most common categories of such new activities involved money and sex. Individuals would give money away, buy unneeded things or begin unsound business ventures. Previously sober individuals would dress indiscreetly, become flirtatious and engage in sexual behaviors typically judged to be wildly inappropriate by their families and peers.

One symptom (delusions) and one sign (distractibility) were described by 17 of the authors. The descriptions of delusions were of particular interest because they differed strikingly from those reviewed in the parallel project on schizophrenia (Kendler, Reference Kendler2016b ). First, all authors uniformly described the major delusional theme as grandiosity, often noting that the delusions could be easily understood to emerge from the underlying mood state. But a number of authors commented that some patients, often those with more irritability, could manifest paranoid delusions. Second, several authors noted the typical lack of systemization and the instability of the delusional beliefs. Third, the delusions were noted by some to be typically of modest or minor clinical importance. Fourth, a number of these experts noted that the delusions never became ‘ridiculous’ or ‘senseless’ and nearly always remained ‘at least imaginable’. Finally, several authors stated that the delusions often seemed playful and the patient not always convinced of their reality. Distractibility was most commonly understood by the authors as resulting from the rapid shifting of attention that typically occurred in mania with the particular sensitivity to both internal and especially external stimuli.

One sign, disorganization of speech, was noted by 16 of these authors. Several features of the typical manic thought disorder were noted. First, increased rapidity of speech was nearly always seen in part a result of their distractibility. The patients rapidly changed topics as their thoughts became attracted to one after another of the ideas continually welling up in their consciousness. Second, the playfulness of the thought disorder was often commented on with authors noting the frequency of rhyming and alliterations, with associations often being driven by similarity in sound (e.g. clang associations) rather than content. Third, authors frequently observed the degree of thought disorder closely paralleled the general level of activation of the patient reaching levels of incoherence with severe manic excitement.

Category B symptoms/signs

Two symptoms (hallucinations and feelings of well-being) and four signs (altered sleep, relaxation of prior moral standards, increased humor, and hypergraphia) were described by 12 to 15 of these 18 authors.

In contrast to what was seen in the parallel review with schizophrenia (Kendler, Reference Kendler2016b ), with mania, the authors often noted the hallucinations – typically auditory – were rare and most commonly fleeting in occurrence. While altered sleep was noted as typical for mania by 15 authors, many of these authors simply described disturbed sleep patterns or insomnia. Only 8 authors described a decreased need for sleep, often commenting on the tendency of patients to awaken very early in the morning after a short sleep feeling refreshed.

While change in moral standards might be considered a generic manifestation of ‘poor judgment in new activities’, it appeared in many descriptions to be sufficiently distinct to merit separate description. These authors noted that the underlying moral character of the individual seemed to change during the manic episode. The solid, trustworthy banker writes bad checks. The minister, a scion of moral probity in his community, frequents a brothel. The proper social matron dresses provocatively, flirts extensively and engages in sexual affairs entirely out of keeping with her prior character.

While feelings of well-being might be considered only a manifestation of elevated mood, the authors who described this symptom noted that it extended beyond mood to include feelings of physical and mental robustness. The phrase ‘Never felt better in my life’ or something similar recurred in their descriptions. Similarly, increased sexual behavior might be understood to result solely from a decline in inhibitions. However, 12 authors specially noted a mania-associated increase in sexual drive which, when combined with the reduction of inhibitions, was noted to have a range of adverse consequences.

Twelve authors also noted an increase in humor. Several of them commented that the quick witted and frequently mischievousness comments of their manic patients were often genuinely funny and typically quite out of keeping with their prior demeanor. Their humor was often infectious.

Appetite changes was amongst the least consistent of the reported symptoms/signs. Few authors commented on actual changes in the appetitive drive. Most noted only that the manic patients were too preoccupied to eat or when they did wouldn't finish their meals because they were too soon up and about. But some noted an increase in appetite or that the appetite was generally good. This contrasts, for example, with the very frequently reported symptom of reduced appetite in depression (Kendler, Reference Kendler2016a ).

Several of the twelve textbook writers who described hypergraphia commented on its close relationship with flight of ideas. It was, several often noted, just the written version of the same symptom. A number also commented on the large bold letters and flourishes that characterized the writing of the manic patients, and several, including Kraepelin, providing handwriting examples in their textbooks.

Category C symptoms/signs

Five symptoms or signs of mania were reported by ten or fewer authors: weight change, impulsivity, physical appearance, mood lability, and lack of insight. The descriptions of weight change, like appetite change, were not consistent. Weight loss was reported more frequently than weight gain and often was described as secondary to periods of marked excitement. Impulsivity, lack of insight and mood lability were often implied in the clinical descriptions of our authors, but each were only commented on explicitly by a moderate number. Particularly interesting were the nine authors who commented on the robust, healthy, physical presentation of their manic patients. Noyes wrote ‘in excellent health. The eyes are bright, the face flushed, the head erect and the step quick’ (Noyes, Reference Noyes1936, p. 202).

Prominent symptoms/signs

Nine authors reported particular symptoms and signs they felt were primary to the diagnosis of mania. All nine described the same three features emphasized by Kraepelin in our introductory quote: elevated mood, hyperactivity and increased rate of speech (Table 1). One prominent sign was noted by three authors (irritability) and four other features by only one.

Relationship of text descriptions to US operationalized diagnostic criteria

Table 2 summarizes the symptomatic diagnostic criteria for mania in the six major US operationalized systems for psychiatric diagnosis. Three technical issues arose in mapping the list of symptoms and signs to these criteria. First, the Feighner, RDC and DSM-III systems stated that the grandiosity may be delusional, but this wording was absent in DSM-III-R, DSM-IV and DSM-5. Second, for sleep changes, the Feighner criteria listed ‘decreased sleep’, while all other systems listed ‘decreased need for sleep’. Third, compared to my reports on sleep changes to these criteria, I needed to create separate symptoms for our 15 authors who commented on altered sleep and the subset of them (eight authors) who specifically noted a reduced need for sleep.

Table 2. A comparison between the symptoms and signs of mania described by textbook authors from ~1900 to 1960 and the criteria of major US operationalized psychiatric diagnostic systems*

RDC, Research Diagnostic Criteria; APA, American Psychiatric Association.

* Category A, B and C criteria are depicted in italics, bold and normal type, respectively.

Taking these subtleties into account, we see a very strong association between the frequency with which particular signs and symptoms of mania were noted by the authors and the likelihood they were included in modern operationalized criteria (Table 2). This can be tested by calculating the proportion of symptoms and signs in these three categories which were included in our diagnostic systems. For categories A, B and C, these proportions were 45/54 (83%), 1/36 (3%) and 5/36 (14%) (χ2 = 72.9, df = 2, p < 0.0001). Indeed, the only modern diagnostic criterion for mania not commented on by a large majority of these authors was decreased need for sleep.

Discussion

My initial goal was to present the important signs and symptoms of mania as described in psychiatric textbooks that adopted a Kraepelinian diagnostic perspective and were published in Europe and the US from ~1900 to 1960. Twenty-two signs and symptoms were noted by more than five authors. Six noteworthy conclusions might be drawn from this effort. First, over six decades and two continents, a high degree of agreement was evident regarding the core symptoms and signs of mania. Six clinical features were described by every author: elevated mood, hyperactivity, increased rate of speech, irritability, grandiosity, and poor judgment in new activities. The degree of consensus regarding the key features of mania was substantially greater than that found for depression (Kendler, Reference Kendler2016a ) and schizophrenia (Kendler, Reference Kendler2016b ), where, respectively, 2/18 and 3/20 clinical features were described by all authors. Subjectively, in reviewing these texts, there was, for mania, a substantially greater sense of homogeneity in the descriptions than was evident for depression or schizophrenia. Perhaps this was a result of a greater a priori agreement among the authors of the key signs to look for in mania. However, my impression was that the manic patients described by these authors were actually more similar to one another than was the case for their patients with depression and schizophrenia.

Second, nine authors listed what they regarded as cardinal features of mania. All of these noted three signs and symptoms (elevated mood, hyperactivity, and increased rate of speech) which might together be viewed as the core symptomatology of mania.

Third, while mania is typically characterized as a mood or affective disorder, a review of the symptoms and signs of our authors reveals a striking diversity of symptomatology. We see changes in motor behavior, language, self-concept, judgment, attention, sexuality, sleep, appetite, impulsivity, and sense of humor.

Fourth, a number of the authors spoke of the change of personhood – that with respect to humor, business plans, attitude toward money, sexual behaviors, moral judgments – the manic individual often acted quite out of keeping with their prior character. They were not the same person.

Fifth, although we are commonly taught about the problem of the differential diagnosis of mania and schizophrenia (Pope & Lipinski, Reference Pope and Lipinski1978), this difficulty was not evident in these textbook descriptions. Indeed, the authors minimized the importance of psychotic symptoms in mania. Hallucinations were typically fleeting. Delusions were rarely fixed, mood-congruent and (with the exception of Kraepelin's description) neither fantastic nor bizarre. However, the differential diagnosis with schizophrenia would likely be more difficult had I included in this review the category of ‘confusional’ or ‘delirious’ mania.

Sixth, of the 22 key clinical features of mania, only 6 (27%) were symptoms and the remainder signs. This is similar to what we found for schizophrenia (5/19 = 26%) (Kendler, Reference Kendler2016b ) but quite different from that found for major depression (14/18 = 78%) (Kendler, Reference Kendler2016a ). Clinician psychiatric experts of the 20th century relied much more on self-report for the diagnosis of depression than for mania or schizophrenia where clinical observations were more important.

Described symptoms and signs and diagnostic criteria

Our second goal was to compare the historical experts’ views on the important clinical features of mania with those included in our modern operationalized diagnostic criteria. Four points are noteworthy. First, a striking consilience was observed between the historical experts and modern nosologic systems. Aside from the criterion describing sleep changes, every other diagnostic criterion for mania used in these systems were reported by at least 16 of our authors and nearly two-thirds of all these criteria were reported by all the authors. A greater degree of agreement is seen between historical experts and modern diagnostic criteria for mania than for depression (Kendler, Reference Kendler2016a ) or schizophrenia (Kendler, Reference Kendler2016b ).

Second, operationalized criteria for mania have changed very modestly since the Feighner criteria, in notable contrast to schizophrenia (Kendler, Reference Kendler2016b ). Although a quite variable syndrome in its early history, being used at various time to describe states of frenzy, agitated psychosis or just generic insanity (Berrios, Reference Berrios1981, Reference Berrios2004; Healy, Reference Healy2008; Kendler, Reference Kendler2015), since around 1900 under the influence of Kraepelin's diagnostic formulation, the syndrome of mania in Western psychiatry has been relatively stable. This means that the rise of effective pharmacologic treatment of mania, first lithium and then a range of other mood-stabilizers in the second half of the 20th century (Healy, Reference Healy2008), did not produce major shifts in the definition of the manic syndrome.

Third, despite the consilience, some important clinical features of mania noted by historical experts are not present in any of our operationalized criteria. Some are likely familiar to modern diagnosticians (impulsivity, hallucinations, hypersexuality, and mood lability) but others are less commonly discussed including changed moral standards, increased humor, hypergraphia (perhaps manifest differently in our electronic age), and a vigorous physical appearance.

Fourth, the list of manic symptoms and signs developed for this project, which reflects something of a post-Kraepelin diagnostic consensus, can be used as a tool for historical research. How far back into the psychiatric writings of the 19th century are manic syndromes described using a closely similar set of signs and symptoms (Berrios, Reference Berrios1996)? This can help us clarify the degree to which Kraepelin's concept of mania was largely novel or was a syndrome well recognized by his key predecessors in the last half of the 19th century.

It is useful to ask how often symptoms and signs given by our textbook authors that were not in the DSM criteria was mentioned in the accompanying text. To investigate this, I examined the DSM-5 text for bipolar I disorder. Of the 14 symptoms/signs noted in our reviewed textbooks that were not in the DSM-5 criteria, six (delusions of grandeur, disorganization of speech, increased humor, hypergraphia, hypersexuality and mood lability) were described in the DSM text.

The appropriate role for diagnostic criteria in research, clinical work and teaching

Our final goal, considered in greater depth in the first article in this series (Kendler, Reference Kendler2016a ), was to use this study to help clarify the optimal role for diagnostic criteria in our research, clinical work and teaching. For mania, more than for depression or schizophrenia, our operationalized diagnostic criteria do a good job of assessing symptoms and signs regarded as crucial by historical experts. But the overlap is far from complete. Fourteen of the 22 symptoms and signs of our experts are not found in DSM-5. This is not a problem for DSM-5 if diagnostic criteria serve an indexical function – to be easy to use and to identify cases with low error rates. But – and this is the central point – DSM criteria do not and should not list every important symptom and sign. It follows then that diagnostic criteria should not be the sole focus of teaching, clinical work or research. That is, our operational criteria for mania should not be viewed as completely describing the clinical syndrome. Such an approach will alleviate the problems that have led to the reification of our diagnostic categories, taking a fallible index of something for the thing itself (Hyman, Reference Hyman2010).

Limitations

This work should be interpreted in the context of three potential methodological limitations. First, I have surely not exhaustively reviewed the major diagnostic writings on mania in the post-Kraepelin Western Psychiatric tradition. I have under-sampled non-Anglophonic authors. Hopefully the result remains broadly representative. Second, in such a project, it is always a concern that one textbook writer just copies material for an earlier textbook. I was alert to this concern and found no such examples.

Third, psychiatric practice during the 20th century moved from largely asylum-based work to the out-patient clinic. Most of the patients with mania seen by our authors were in-patients and often quite ill. This could contribute to differences between mania as seen by the earlier authors and our more modern diagnostic systems. However, their descriptions included a wide variety of severities of mania, reducing my concerns about the ‘biased’ nature of their patient samples. In addition, it is possible that changing concepts of the boundaries between mania and other psychiatric disorders, especially dementia praecox/schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder, could contribute to differences between older and more recent diagnostic concepts of mania.

Declaration of Interest

None.