Introduction

Suicide is one of the leading causes of death worldwide and reducing the rate of its occurrence is a global imperative (Lozano et al., Reference Lozano, Naghavi, Foreman, Lim, Shibuya, Aboyans and Murray2012; World Health Organization, 2014). One of the top three risk factors for suicide deaths (Franklin et al., Reference Franklin, Ribeiro, Fox, Bentley, Kleiman, Huang and Nock2017), and an important clinical concern in its own right, is suicidal ideation. Understanding the phenomenology and etiology of suicidal thoughts is therefore essential for advancing strategies to assess the risk for and to prevent suicidal behavior. Suicidal ideation ranges in severity from passive ideation (i.e. a desire to be dead) to active ideation (i.e. a desire to kill oneself). The idea that passive ideation is of comparably moderate clinical severity may often lead to the conclusion in suicide risk assessments that individuals presenting with passive ideation are at relatively lower risk than those with active ideation for engaging in suicidal behavior, and to decisions regarding clinical care being made accordingly (Jacobs, Reference Jacobs2009; National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention, 2014; Simon, Reference Simon2014). It is uncertain, however, to what degree this position is empirically supported. Moreover, in a recent report commissioned by the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention has put forth the view that passive ideation may in fact be comparable to active ideation in its association with negative mental health outcomes, including suicidal behavior (National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention, 2014).

Hindering critical evaluation of this issue is the relative want of research on passive ideation, especially compared to the considerable body of the empirical literature on active ideation. Indeed, prevalence estimates of suicidal ideation in several of the most important epidemiological surveys to date [e.g. the World Health Organization World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative (WHO World Mental Health Survey Consortium, 2004) as well as the National Comorbidity Survey Replication and Adolescent Supplement (NCS-R and NCS-A; Husky et al., Reference Husky, Olfson, He, Nock, Swanson and Merikangas2012; Kessler, Berglund, Borges, Nock, & Wang, Reference Kessler, Berglund, Borges, Nock and Wang2005; Nock et al., Reference Nock, Green, Hwang, McLaughlin, Sampson, Zaslavsky and Kessler2013)] are in actuality of active ideation only. That passive ideation has received less attention in clinical research is also reflected by the fact that several of the most essential measures of depression and suicide include assessments of active but not passive ideation (e.g. Beck, Brown, & Steer, Reference Beck, Brown and Steer1996; Kessler & Üstün, Reference Kessler and Üstün2004; Kovacs, Reference Kovacs2010; Osman et al., Reference Osman, Bagge, Gutierrez, Konick, Kopper and Barrios2001). Consequently, several fundamental aspects of passive ideation remain poorly understood. This relative neglect of passive ideation in the empirical literature is doubtless in some measure a reflection of the greater clinical importance accorded active ideation in comparison to passive ideation. The clinical weight of passive ideation is therefore unclear, and insofar as passive ideation is clinically important, the scale of suicidal ideation as a public health problem is likely to be significantly underestimated in epidemiological data.

As an important step toward characterizing the phenomenology of passive ideation and its clinical significance, the current review provides a quantitative synthesis systematically characterizing the empirical literature to date on passive ideation. First, pooled estimates of the prevalence of passive ideation were calculated for different time-frames (e.g. current/past week and lifetime) and populations (e.g. psychiatric and community). Pooled effects were derived for sociodemographic, clinical, psychological, and other correlates of passive ideation. For each of these correlates, corresponding pooled effects from the same studies were also calculated for active ideation, thereby to facilitate comparisons between passive and active ideation. For this reason too, pooled effects were also calculated whenever possible for direct comparisons between active and passive ideation with respect to correlates of interest. Thus, we aimed to address the following, with active ideation serving as a reference point: (i) what are the sociodemographic characteristics associated with passive ideation; (ii) the psychiatric comorbidity of passive ideation, thereby providing a preliminary evaluation of the clinical importance of passive ideation; and (iii) the strength of psychological and environmental correlates of passive ideation, thereby identifying candidate risk factors to be evaluated in future research ultimately to inform future risk identification and clinical intervention strategies.

Method

Search strategy and eligibility criteria

A systematic search of the literature was conducted in PsycINFO and MEDLINE to identify the studies of potential relevance to the current review published from inception to 9 September 2019. The following search string was applied: (passive and suicid*) OR ‘passive SI’ OR ‘desire for death’ OR ‘suicidal desire’ OR ‘death ideation’ OR ‘thought of death’ OR ‘thoughts of death.’ The search results were limited to: (i) English-language publications and (ii) peer-reviewed journals. This search strategy yielded a total of 2192 articles, of which 1668 were unique reports. In cases where the eligibility of an article could not be ruled out based on the title and abstract, the full text was also examined.

The study inclusion criteria were: (i) passive ideation was analyzed separately from other constructs (e.g. active ideation); (ii) passive ideation was assessed systematically over a standardized time-frame; and (iii) quantitative data were presented on either the prevalence of passive ideation or its correlates. In the case of studies where more information on the measurement of the constructs of interest was needed to determine study eligibility, every effort was made to obtain additional details in other publications describing the measure (e.g. other publications based on the same dataset) or by contacting the corresponding author.

Data extraction

We extracted data for six study characteristics. These included three sample characteristics: (i) mean age of sample, (ii) sample type (i.e. epidemiological, community, at-risk/mixed/medical, and psychiatric), and (iii) percentage of female participants in the study sample. Data for three study design characteristics were also extracted: (i) suicidal ideation instrument (i.e. self-report v. interview), (ii) time-frame of suicidal ideation assessment, and (iii) whether an assessment of ‘pure’ passive suicidal ideation was used (i.e. passive ideation without co-occurring active ideation).

Data analysis

All analyses were conducted with Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Version 3.3.070 (Biostat, 2014). The standardized mean difference (SMD; Cohen's d) was used as the primary index of effect size for analyses of potential correlates of passive and active ideation, respectively. An SMD of 0.20 is interpreted as a small effect size, 0.50 as medium, and 0.80 as large (Kraemer et al., Reference Kraemer, Morgan, Leech, Gliner, Vaske and Harmon2003). All pooled effects were calculated such that values >0 reflected a positive association between the correlate of interest and suicidal ideation (i.e. the correlate is associated with greater experiences of suicidal ideation). For analyses directly comparing passive to active ideation with respect to a given correlate of interest, effect sizes were calculated such that values larger than zero indicated that the correlate was more strongly associated with active than passive ideation. Weighted effect sizes were calculated by pooling effects across all relevant studies. For all analyses, random-effects models were generated in preference to fixed-effects models, so as to account for the high expected heterogeneity across studies resulting from differences in samples, measures, and design. Random-effects models are more appropriate than fixed-effects models in cases where high heterogeneity is observed, in that they account for this heterogeneity by incorporating both sampling and study-level errors, with the pooled effect size representing the mean of a distribution of true effect sizes instead of a single true effect size. In contrast, fixed-effects models estimate only within-study variance, as it assumes that a single true effect size exists across all studies and any variance detected is due strictly to sampling error. Heterogeneity across the studies was evaluated using the I 2 statistic. I 2 indicates the percentage of the variance in an effect estimate that is due to heterogeneity across studies rather than sampling error (i.e. chance). Low heterogeneity is indicated by I 2 values of around 25%, and moderate heterogeneity by I 2 values of 50%. Substantial heterogeneity that is due to real differences in study samples and methodology is indicated by an I 2 value of 75%, which suggests that the observed heterogeneity is more than would be expected with random error (Higgins, Thompson, Deeks, & Altman, Reference Higgins, Thompson, Deeks and Altman2003).

High heterogeneity indicates the need to conduct moderator analyses to account for potential sources of this heterogeneity. Each potential moderator was assessed individually, with the effect size at each level of the moderator estimated. Additionally, given that passive and active ideation often co-occur, moderator analysis was conducted to determine whether the prevalence estimates for passive ideation differed as a function of whether individual studies assessed ‘pure’ passive ideation.

A common concern in conducting meta-analyses is the possibility of publication bias. Studies with small effect sizes or non-significant findings are less likely to be published, and thus may be more likely to be excluded from meta-analyses, resulting in a potentially inflated estimate of the overall effect size. The following publication bias indices were calculated to assess for the presence of potential publication bias: Duval and Tweedie's trim-and-fill analysis (Duval & Tweedie, Reference Duval and Tweedie2000) and Egger's regression intercept (Egger, Davey Smith, Schneider, & Minder, Reference Egger, Davey Smith, Schneider and Minder1997). Duval and Tweedie's trim-and-fill analysis produces an estimate of the number of missing studies based on the asymmetry in a funnel plot of the standard error of each study in a meta-analysis (based on the study's sample size) against the study's effect size. This analysis also calculates an effect size estimate and confidence interval, adjusting for these missing studies. It is important to note that this procedure assumes homogeneity of effect sizes, and thus, its results must be interpreted with a degree of caution in cases where significant heterogeneity is present. Egger's regression intercept also provides an estimate of potential publication bias using a linear regression approach assessing study effect sizes relative to their standard error.

Results

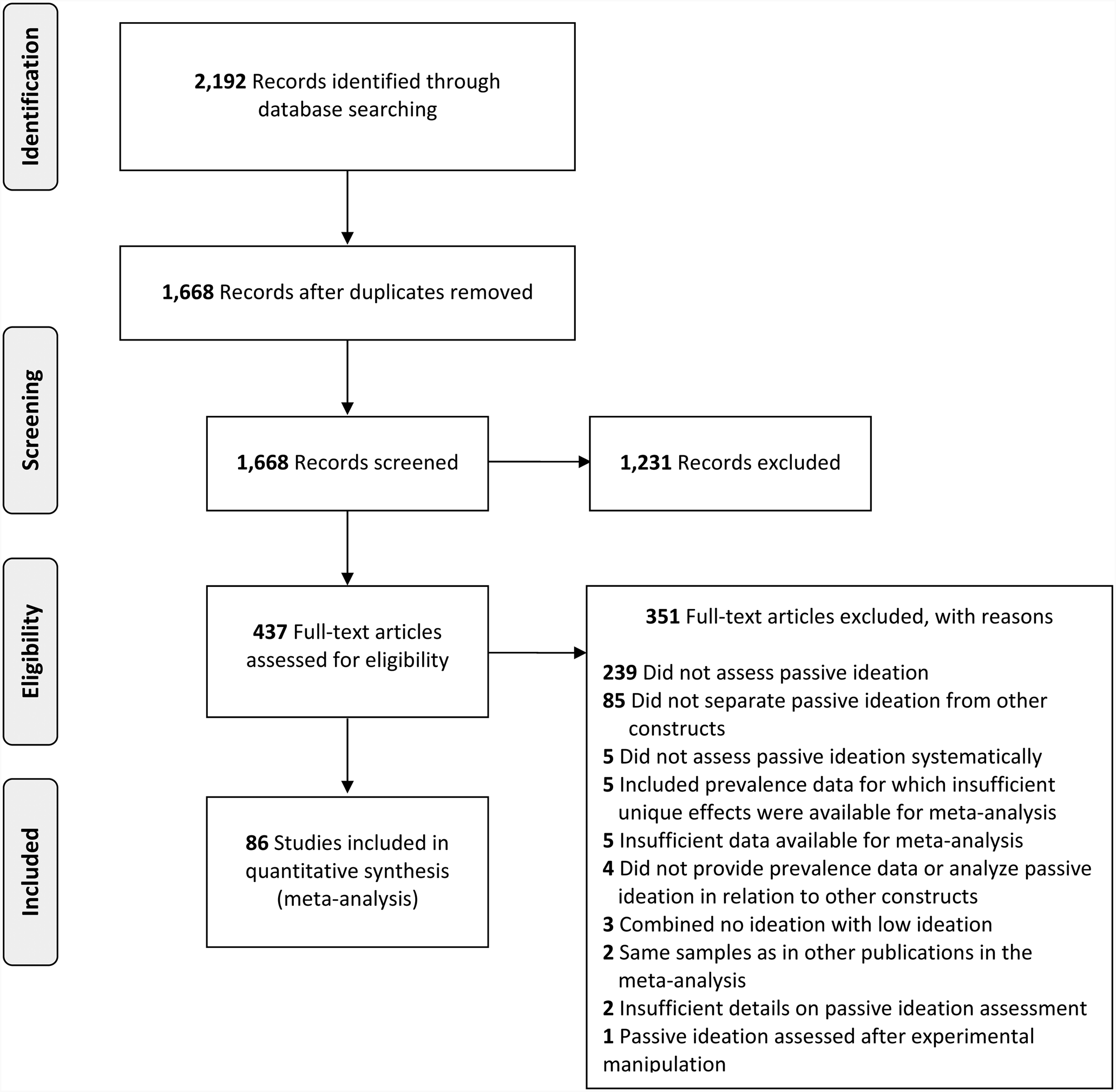

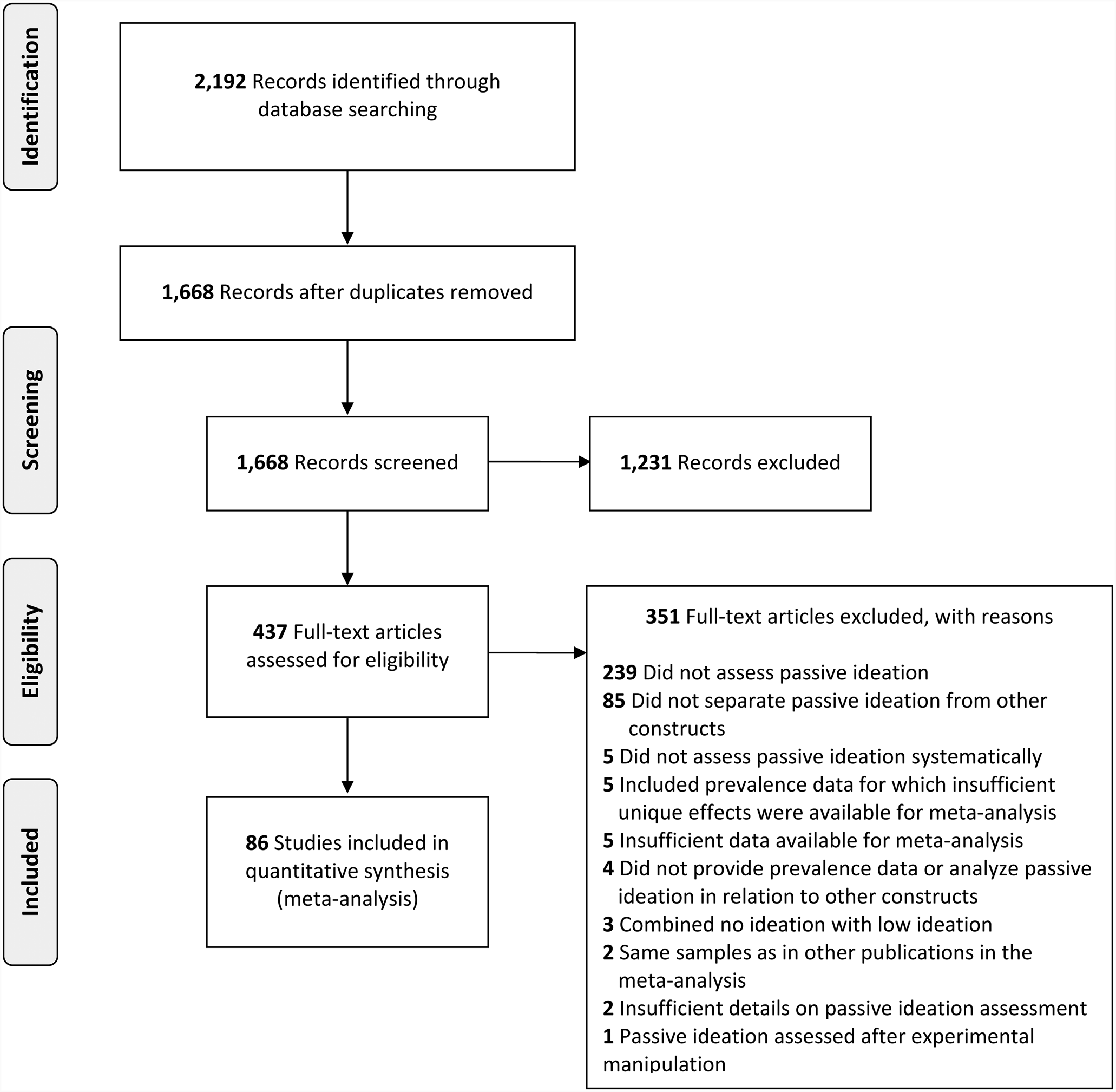

Based on the inclusion criteria, we excluded 1231 reports based on their titles and abstracts. After this initial screen, 344 additional reports were excluded based on a detailed full-text review, resulting in 93 studies satisfying the eligibility criteria. Additional data required for meta-analysis were obtained from the authors of seven of these studies (Barrigón et al., Reference Barrigón, Berrouiguet, Carballo, Bonal-Giménez, Fernández-Navarro, Pfang and Baca-García2017; Glassmire, Tarescavage, Burchett, Martinez, & Gomez, Reference Glassmire, Tarescavage, Burchett, Martinez and Gomez2016; Guidry & Cukrowicz, Reference Guidry and Cukrowicz2016; Handley, Adams, Manly, Cicchetti, & Toth, Reference Handley, Adams, Manly, Cicchetti and Toth2019; Jahn, Poindexter, Graham, & Cukrowicz, Reference Jahn, Poindexter, Graham and Cukrowicz2012; Rufino, Viswanath, Wagner, & Patriquin, Reference Rufino, Viswanath, Wagner and Patriquin2018; Tal et al., Reference Tal, Mauro, Reynolds, Shear, Simon, Lebowitz and Zisook2017). Five studies included prevalence data for which not enough unique effects existed for meta-analysis (e.g. 6 days) and were thus excluded from this review. For studies with overlapping samples, determination of which study to include in the meta-analysis was based, in descending order, on: (i) inclusion of sufficient reported data for meta-analysis and (ii) largest sample size for the relevant analysis. In cases where two studies used overlapping samples but examined different associations (e.g. passive ideation with different correlates), both studies were retained for the relevant analyses. Whenever it remained unclear after full-text inspection whether two studies reported on overlapping samples, the study authors were contacted to seek clarity on this issue. Seventeen studies featured overlapping samples and two were excluded at this stage, resulting in a final set of 86 studies included in the current review (see Fig. 1 and Table 1). Only three of these studies featured longitudinal analyses with passive ideation as an outcome (Nrugham, Larsson, & Sund, Reference Nrugham, Larsson and Sund2008; Raue, Meyers, Rowe, Heo, & Bruce, Reference Raue, Meyers, Rowe, Heo and Bruce2007; Schimanski, Mouat, Billinghurst, & Linscott, Reference Schimanski, Mouat, Billinghurst and Linscott2017), precluding consideration of this design feature in the analyses of correlates.

Fig. 1. PRISMA flow chart of literature search.

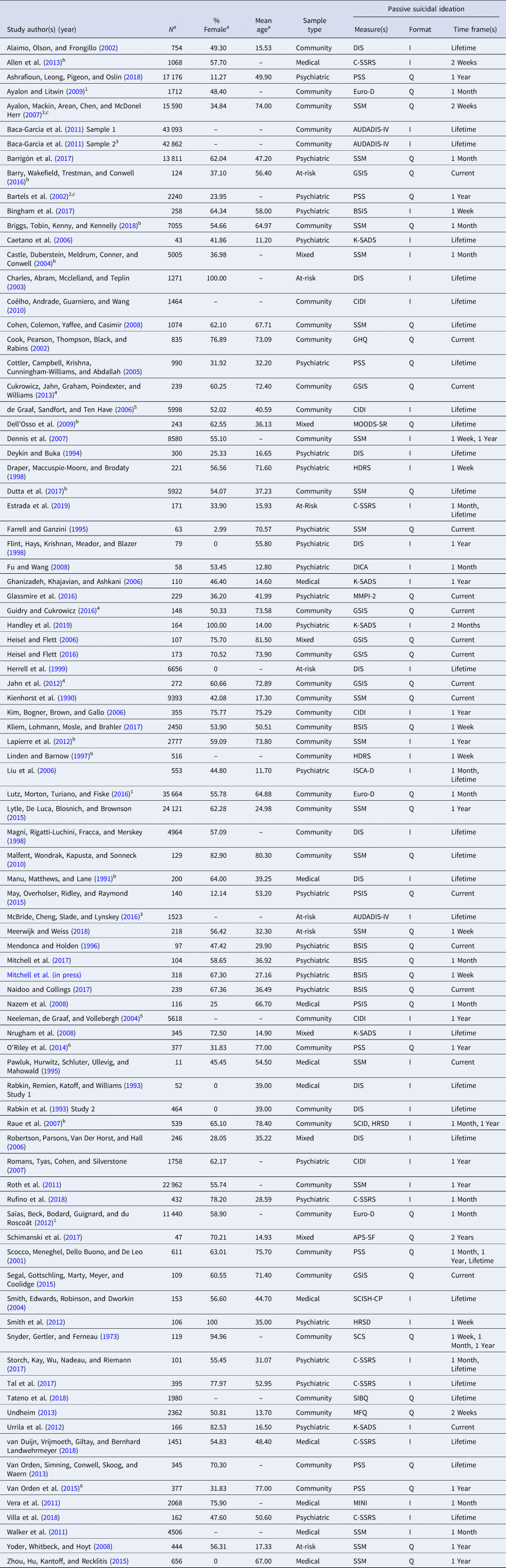

Table 1. Study characteristics

APS-SF, Adolescent Psychopathology Scale – Short Form; AUDADIS-IV, The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV; BSIS, Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation; CIDI, Composite International Diagnostic Interview; C-SSRS, Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale; DICA, Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents; DIS, Diagnostic Interview Schedule; GHQ, General Health Questionnaire; GSSI, Geriatric Scale for Suicide Ideation; HRSD, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; ISCA-D, Interview Schedule for Children & Adolescents – Diagnostic Version; K-SADS, Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia; MINI, Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview; MMPI-2, Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory; MOODS-SR, Mood Spectrum Self-Report; PSS, Paykel Suicide Scale; PSIS, Passive Suicide Ideation Scale; SCISH-CP, Structured Clinical Interview for Suicide History in Chronic Pain; SCS, Social Concerns Scale; SIBQ, Suicide Ideation and Behavior Questionnaire; SSM, study-specific measure; I, interview; Q, questionnaire.

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6Studies with identical superscripts were drawn from same or overlapping samples but presented unique data included in this review.

a The sample size, mean age, and percentage female for participants included in relevant analyses, rather than of the entire study sample, are presented and were incorporated in moderator analyses whenever available. For ease of presentation, whenever the sample size, mean age, or percentage female varied across multiple relevant analyses within a study, data for the cumulative number of unique participants across these analyses are presented here, and the sample size used in each analysis was retained in the relevant meta-analysis for purposes of obtaining weighted effect sizes.

b These studies allowed for estimates of the prevalence of passive ideation in a clinical subgroup of the full study sample.

c These studies drew from a sample that overlaps with those of others included in this review but conducted analyses with a different measure of suicidal ideation.

Prevalence of passive ideation

Pooled prevalence rates for passive ideation were calculated for four different sample types (epidemiological, community, at-risk/mixed/medical, and psychiatric) across four different time-frames (current/1-week, 1 month, 1 year, and lifetime). Epidemiological samples were a subset of those included in the analyses of community samples. The prevalence of passive ideation was highest in psychiatric samples, ranging from 33.57% for current/1-week ideation to 47.03% for lifetime ideation, and lowest in epidemiological samples, ranging from 2.35% for current/1-week ideation to 10.57% for lifetime ideation (Table 2).

Table 2. Prevalence rates for passive suicidal ideation by sample type

CI, confidence interval; k, number of unique effects; N, total number of participants included in pooled analyses.

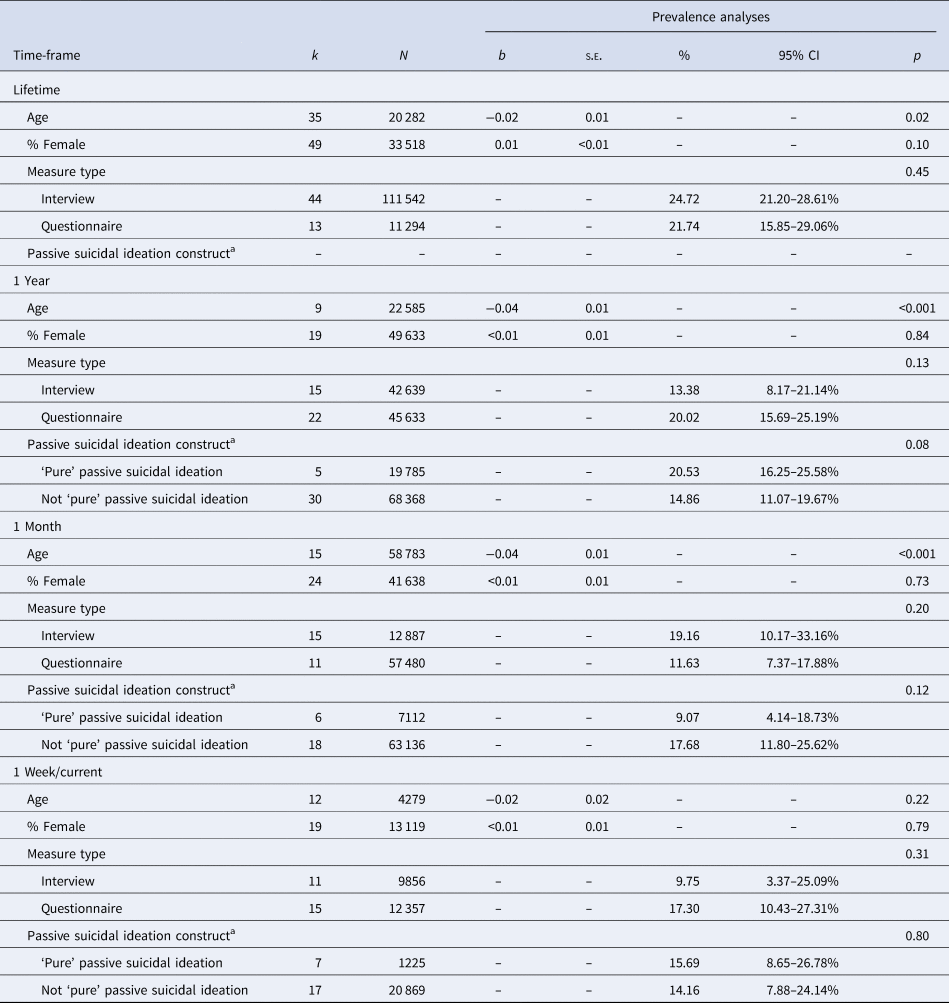

Heterogeneity was uniformly high across all prevalence analyses, indicating that moderator analyses were warranted. Moderator analyses were conducted for each time-frame, with age, percentage of female participants in each sample, and measure type (i.e. self-report v. interview) evaluated as candidate moderators. Results were generally consistent across the four time-points (Table 3). Specifically, age significantly moderated prevalence estimates for all time-frames, with the exception of current/1-week passive ideation. For the three remaining time-frames, age was negatively associated with the prevalence of passive ideation; samples with a lower mean age generally had higher prevalence rates than did samples with a higher mean age. Neither sample sex composition nor measure type emerged as a significant moderator of passive ideation prevalence rate for any time-frame. Prevalence estimates for passive ideation did not differ as a function of whether ‘pure’ passive ideation was assessed or if passive ideation was assessed irrespective of the co-occurrence of active ideation.

Table 3. Moderator analyses for the prevalence of passive suicidal ideation

CI, confidence interval; k, number of unique effects; N, total number of subjects included in pooled analyses.

a In moderator analyses of the construct of passive suicidal ideation, prevalence of ‘pure’ passive suicidal ideation was based only on individuals who endorsed passive but not active suicidal ideation; studies were considered conservatively not to have assessed ‘pure’ passive suicidal ideation if they either included individuals with active ideation in their assessment of passive ideation or were unclear as to whether that decision was made. For lifetime passive suicidal ideation, only one study with two unique effects for ‘pure’ passive suicidal ideation was available for lifetime prevalence of passive suicidal ideation, and thus moderator analysis was not conducted.

Analyses of publication bias were conducted for lifetime prevalence of passive ideation by sample type. Across all analyses, there was relatively little evidence of publication bias. Egger's regression test indicated significant publication bias only in the case of at-risk/mixed/medical samples (intercept = 6.77, p < 0.01) and not for the remaining three sample types (interceptEpidemiological Samples = −0.45, p = 0.88; interceptCommunity Samples = 2.09, p = 0.33; interceptPsychiatric Samples = 3.40, p = 0.26). The trim-and-fill method yielded slightly different lifetime prevalence rates for only epidemiological (adjusted prevalence = 9.74%, 95% CI 8.94–10.96%) and community samples (adjusted prevalence = 14.51%, 95% CI 12.52–16.76%). Evidence of asymmetry in the funnel plots of the effect sizes for all sample types was correspondingly modest, suggesting the limited presence of publication bias (Figs 2a–2d).

Fig. 2. Funnel plots for effect sizes in the meta-analyses. The vertical line indicates the weighted mean effect. Open circles indicate observed effects for actual studies, and closed circles indicate imputed effects for studies believed to be missing due to publication bias. The clear diamond reflects the unadjusted weighted mean effect size, whereas the black diamond reflects the weighted mean effect size after adjusting for publication bias. (a) Lifetime prevalence of passive ideation in epidemiological samples. (b) Lifetime prevalence of passive ideation in community samples. (c) Lifetime prevalence of passive ideation in at-risk/mixed/medical samples. (d) Lifetime prevalence of passive ideation in psychiatric samples.

Correlates of passive and active ideation

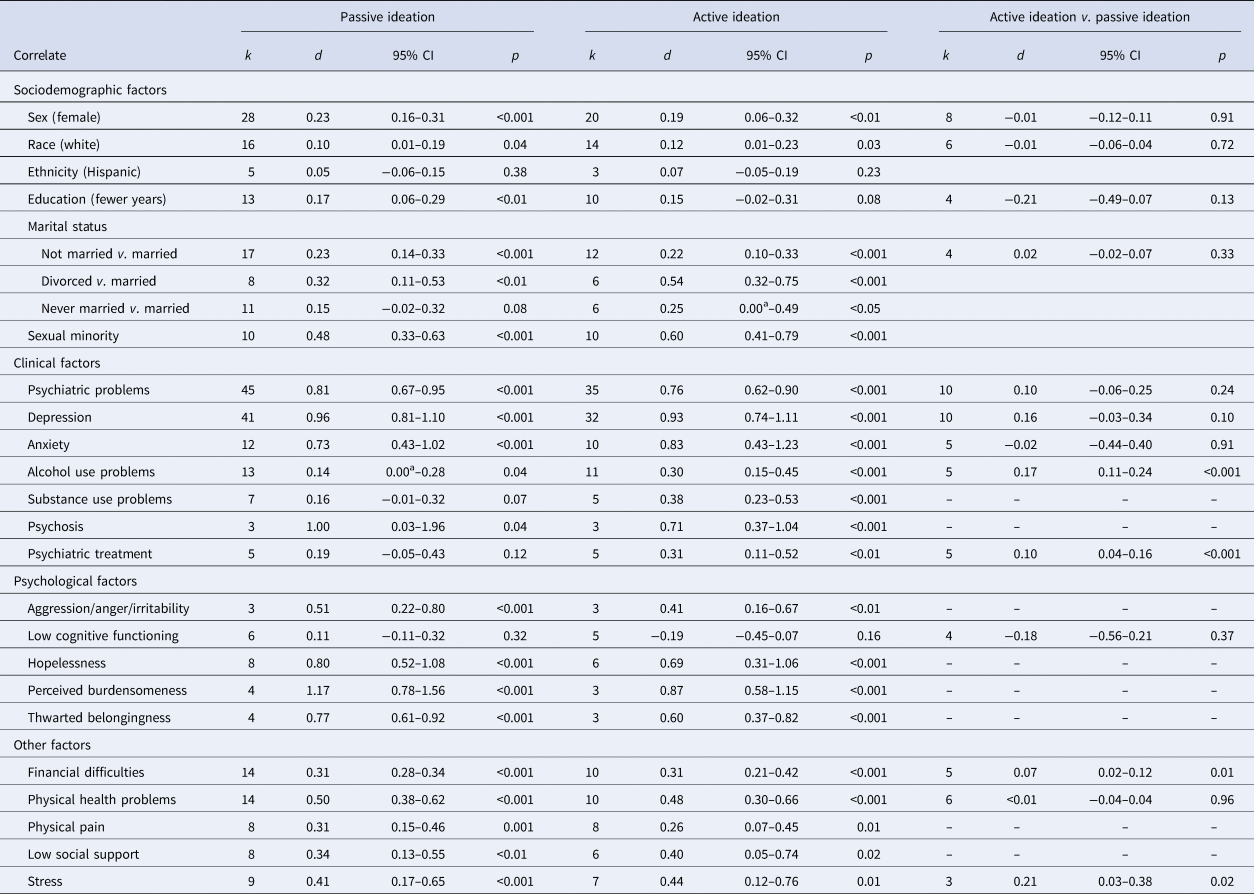

Table 4 presents the results for analyses of correlates of passive and active ideation with all time-frames for suicidal ideation assessment combined, and where possible, of direct comparisons between passive and active ideation with respect to correlates. Most of the effects included in these analyses were for sociodemographic and clinical factors. In general, passive and active ideation were comparable to each other in their relation to the correlates under study.

Table 4. Correlates of passive and active ideation

CI, confidence interval; k, number of unique effects; effect size estimates where k = 3 should be interpreted with a degree of caution.

a The lower end of the confidence interval was rounded down but exceeded 0.

Although passive ideation was significantly correlated with sociodemographic factors, save for ethnic minority status and being never married, the pooled effect sizes were small in almost every case. The exceptions were being divorced, which had a small-to-medium pooled effect, and sexual minority status, with a medium pooled effect. A similar pattern of results emerged for active ideation, the primary difference being that the correlation with education status was no longer significant. In head-to-head comparisons, none of the sociodemographic factors significantly differentiated between passive and active ideation, and pooled effect sizes ranged from trivial to small.

The largest effects of passive ideation were observed for clinical and psychological factors. In the case of the former, generally large and significant pooled effects were found for psychiatric problems, depression, anxiety, and psychosis. Only substance use and psychiatric treatment were not significantly correlated with passive ideation. A similar set of results was found for active ideation, again with the largest pooled effects for psychiatric problems, depression, anxiety, and psychosis. Additionally, small-to-medium significant pooled effects were evident for active ideation in relation to substance use and psychiatric care. In direct comparisons of passive and active ideation, small significant pooled effects indicating a stronger association with active ideation were observed for alcohol use problems and psychiatric treatment utilization. As for psychological factors, all except for cognitive functioning were associated with passive ideation, with large pooled effects in every case. These findings were largely mirrored in the analyses of active ideation, again with only cognitive functioning demonstrating a non-significant association and large pooled effects detected for all other factors. Direct comparison between passive and active ideation was only possible for cognitive functioning and a non-significant pooled effect was found.

All remaining factors, relating to difficulties in financial, physical, and interpersonal domains, as well as general stress, were significantly correlated with passive ideation, with the size of pooled effects ranging from small-to-medium to medium. Results for active ideation were essentially the same, with small-to-medium and medium pooled effects observed across the factors under consideration.

Finally, analyses were conducted evaluating the association between passive ideation and suicide-related outcomes, specifically suicide attempts and deaths (Table 5). A large pooled effect was observed for passive ideation in relation to suicide attempts.Footnote 1Footnote † This was also the case for the association between active ideation and attempts. Given the clinical interest in whether passive and active ideation differ in their association with suicide attempts, a preliminary analysis was conducted of this head-to-head comparison with the two available relevant studies, and a small, non-significant pooled effect was found. For the same reasons, preliminary analyses were conducted for passive and active ideation, respectively, predicting suicide deaths. Large pooled effects were detected in both cases. As only two unique effects were included in each of these preliminary analyses, caution should be taken in interpreting their results.

Table 5. Prediction of suicide attempts and deaths by passive and active ideation

CI, confidence interval; k, number of unique effects; effect size estimates where k = 2 should be interpreted with a degree of caution.

Discussion

The aim of the current review was to characterize the existing literature on passive ideation, particularly the prevalence of this clinical phenomenon, its associated sociodemographic characteristics, the nature of its psychiatric comorbidity, and its psychological and environmental correlates. Furthermore, it aimed systematically to evaluate the degree to which passive ideation differs from active ideation in the strength of its association with these correlates.

Passive ideation was highly prevalent in psychiatric populations, with approximately a third of all individuals experiencing current passive ideation and almost half of all individuals having a lifetime history of passive ideation. Although considerably lower, the prevalence of passive ideation is still concerning in epidemiological studies. Pooled estimates from these studies revealed that approximately one in 20 individuals in the general population experience passive ideation in any given year, and this figure increases to one in 10 individuals for a lifetime passive ideation. The 1-year prevalence of passive ideation in epidemiological samples (5.8%) was somewhat higher than for active ideation reported in the NCS-R (3.3%; Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Berglund, Borges, Nock and Wang2005) and NCS-A (3.6%; Husky et al., Reference Husky, Olfson, He, Nock, Swanson and Merikangas2012). Lifetime prevalence of passive ideation in epidemiological samples in the current meta-analysis (10.6%) fell within the range of lifetime rates reported for active ideation in the WMH surveys (9.2%; Nock et al., Reference Nock, Borges, Bromet, Alonso, Angermeyer, Beautrais and Williams2008a), NCS-A (12.1%; Nock et al., Reference Nock, Green, Hwang, McLaughlin, Sampson, Zaslavsky and Kessler2013) and NCS (13.5%; Kessler, Borges, & Walters, Reference Kessler, Borges and Walters1999) There was little evidence that the prevalence estimates in the current review were influenced by publication bias.

That age was inversely related to the prevalence of passive ideation, particularly in the case of lifetime prevalence, is a curious finding warranting discussion. This finding suggests that younger individuals have a higher lifetime prevalence of passive ideation than do older counterparts, a pattern that seems counterintuitive but has also been found for lifetime prevalence of active ideation (Nock et al., Reference Nock, Borges, Bromet, Alonso, Angermeyer, Beautrais and Williams2008a). One possible explanation for the current finding is the presence of a cohort effect, with passive ideation becoming more common among younger individuals. Another explanation may be that older individuals are more likely to forget experiences of passive ideation over time, especially if they occurred many years in the past. Indeed, it is possible that passive ideation might be less memorable compared to active ideation, particularly when recall of its occurrence is over longer periods of time. In support of this latter possibility, one study has found some adolescents to forget previously endorsed suicidal ideation, albeit active ideation, over a 4-year period (Goldney, Smith, Winefield, Tiggeman, & Winefield, Reference Goldney, Smith, Winefield, Tiggeman and Winefield1991). It is also consistent with the broader literature, in which higher rates of psychiatric disorders have been found when assessed prospectively than retrospectively (Liu, Reference Liu2016; Moffitt et al., Reference Moffitt, Caspi, Taylor, Kokaua, Milne, Polanczyk and Poulton2010). These two possibilities, a cohort effect and decreased rates due to forgetting over time, are not mutually exclusive, however, and require additional research to resolve.

Regarding the inverse association for age relative to 1-month and 1-year prevalence of passive ideation, a different explanation is likely relevant. Specifically, active ideation has been found to peak during adolescence and early adulthood (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Borges and Walters1999), an implication of which is that prevalence of current or recent active ideation should be higher among adolescents and young adults than older age groups. It is a reasonable possibility that a similar pattern may hold for passive ideation, and it may therefore be expected to have a higher incidence among younger age groups. The absence of a similar inverse relation between age and current/1-week passive ideation, on the other hand, is likely due to the availability of only one study with a youth sample (Urrila et al., Reference Urrila, Karlsson, Kiviruusu, Pelkonen, Strandholm and Marttunen2012) in the relevant analysis. That is, this modest representation of younger samples likely limited the ability to detect potential moderating effects of age on prevalence rates.

In analyses of correlates, sociodemographic characteristics were generally modestly associated with passive ideation, and are consequently of limited utility in risk screening strategies. As these sociodemographic characteristics are generally easier and quicker to ascertain, and thus more amenable to inclusion in brief clinical risk assessment protocols, than are the other correlates included in this review, this pattern of findings underscores the significant challenges of screening for the risk for passive ideation. One notable exception is sexual minority individuals, who appear to be an especially at-risk population, with a medium pooled effect observed in the current review, a finding that is consistent with the broader suicide literature (Haas et al., Reference Haas, Eliason, Mays, Mathy, Cochran, D'Augelli and Clayton2011; Hottes, Bogaert, Rhodes, Brennan, & Gesink, Reference Hottes, Bogaert, Rhodes, Brennan and Gesink2016; O'Brien, Liu, Putney, Burke, & Aguinaldo, Reference O'Brien, Liu, Putney, Burke, Aguinaldo, Smalley, Warren and Barefoot2017). This group may therefore particularly benefit from increased preventive intervention efforts and be given greater weight when risk stratification is warranted.

Underscoring the clinical significance of passive ideation, it was associated with considerable psychiatric comorbidity as well as psychological characteristics traditionally implicated in the risk for suicide and other negative mental health outcomes, with some of the largest pooled effects being observed for these correlates. These findings appeared most robust for overall psychopathology, depression, and anxiety, based on the number of unique effects available for each analysis and the size of their corresponding pooled effects. Moreover, passive ideation was strongly associated with suicide attempts, and although preliminary, suicide deaths. Indeed, among the largest pooled effects for passive ideation were found in its association with these outcomes. Collectively, these findings point to the need for future research investigating the clinical importance of passive ideation. It is therefore concerning that passive ideation was not associated with the receipt of psychiatric care in our analyses.

Although sizeable pooled effects were observed for the remaining correlates involving general and domain-specific stress (i.e. financial, physical health, social), it is important to note that with most of these correlates (i.e. financial and physical health problems) and associated studies, the focus of research in this area has been predominantly more relevant to adult populations than to youth. Insofar as passive ideation mirrors active ideation with regards to its dramatic increase in the first onset during adolescence (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Borges and Walters1999; Nock, Borges, Bromet, Cha, Kessler, & Lee, Reference Nock, Borges, Bromet, Cha, Kessler and Lee2008b), a discordance exists between where the emphasis has been in the empirical literature and where it is most needed. Although identifying potential markers of risk relevant to passive ideation in adults is undoubtedly important, more research is needed to elucidate potential factors underlying this clinical phenomenon during adolescence, a developmental period of a particular risk. For example, timing of pubertal maturation may be a promising developmentally relevant candidate for future investigation, given that it has been associated with general psychopathology, depression, and anxiety (Hamilton, Hamlat, Stange, Abramson, & Alloy, Reference Hamilton, Hamlat, Stange, Abramson and Alloy2014; Hamlat, Snyder, Young, & Hankin, Reference Hamlat, Snyder, Young and Hankin2019; Reardon, Leen-Feldner, & Hayward, Reference Reardon, Leen-Feldner and Hayward2009; Ullsperger & Nikolas, Reference Ullsperger and Nikolas2017), which as mentioned above, are all strongly correlated with passive ideation.

Of note, these results are cross-sectional in nature, and thus temporal relationships between passive or active ideation and clinical, sociodemographic, suicide-related, and stress-related variables cannot be determined. It is plausible that some correlates may serve as risk factors for the onset and/or maintenance of passive or active ideation, and that these relationships may differ across the lifespan. Alternatively, at least in the case of clinical correlates, it may be possible that passive ideation may prospectively predict negative mental health outcomes, essentially functioning as a prodromal marker of risk, particularly in the case of younger individuals who may be earlier in their clinical course. Prospective research is needed to determine the nature and directionality of these relationships over time to inform screening and intervention efforts.

The similarities between passive and active ideation were notable. Not only were their pooled effects for individual correlates largely equivalent in size, but head-to-head comparisons also consistently yielded trivial to small pooled effects, most of which were not significant. When interpreted together with the aforementioned findings of psychiatric and psychological correlates, the analyses involving active ideation lend weight to the possibility that passive ideation may be comparable to active ideation in terms of clinical significance and associated risk. Although results from this meta-analysis are preliminary, our findings highlight the need for rigorous longitudinal studies to explore whether these associations are maintained over time. Specifically, the most logical next steps are to conduct studies (i) evaluating prospective predictors of passive and active ideation and (ii) directly comparing passive and active ideation in prospectively predicting suicidal behavior. Such a design would permit analyses necessary to be able confidently to evaluate the degree to which passive and active ideation may have a shared or different etiology and the common clinical view that passive ideation is not of high clinical concern.

Several limitations should be mentioned. In spite of the significance of the findings from the current review, there is a near absence of longitudinal studies. As noted above, cross-sectional research provides an important first step for addressing these research questions. Future research, however, should employ longitudinal designs to delineate the temporal nature of observed effects. Such studies are necessary to form the important distinction between concomitants and risk factors, and eventually to elucidate the etiological pathways underlying the risk for passive ideation (Kraemer et al., Reference Kraemer, Kazdin, Offord, Kessler, Jensen and Kupfer1997). Although concomitants are of value for aiding in the identification of who may be currently experiencing passive ideation, risk factors have added importance for potentially enhancing efforts to intervene before the onset of ideation. Work on identifying risk factors is also valuable for its potential to identify targets for the development of future intervention strategies. The possibility that the temporal direction of some of the associations under study may be such that passive ideation is the risk factor, rather than the outcome, should also be considered. For instance, it has been hypothesized that suicidal ideation may lead to prospectively greater rates of interpersonal stress during times of clinical acuity (Liu & Spirito, Reference Liu and Spirito2019). Consistent with this possibility, suicidal ideation has been associated with compromised interpersonal functioning during times of stress (Williams, Barnhofer, Crane, & Beck, Reference Williams, Barnhofer, Crane and Beck2005). This greater interpersonal stress, in turn, may produce feelings of thwarted belongingness in vulnerable individuals.

An additional limitation worth noting is related to the measurement of lifetime suicidal ideation across the studies included in this review. As mentioned above, and like all measurements requiring recall over the lifetime, the assessment of lifetime suicidal ideation may lead to underreporting as a result of memory bias. This type of measurement error may disproportionally affect older individuals, given the greater length of time required for recall. It may also disproportionally affect the recall of less salient content (e.g. passive ideation as compared to active ideation). It is important to consider these potential sources of measurement error when interpreting the current findings. Indeed, these considerations collectively suggest that the prevalence rates of passive ideation reported here may be underestimated and this may especially be the case for older adults.

Additionally, several fundamental characteristics relating to the clinical course of passive ideation (e.g. incidence, chronicity, and recurrence) remain undetermined and await future investigation. Furthermore, individual differences in trajectories of suicidal ideation as a broader construct has been recently observed (Czyz & King, Reference Czyz and King2015; Wolff et al., Reference Wolff, Davis, Liu, Cha, Cheek, Nestor and Spirito2018). For what proportion of individuals does passive ideation specifically abate, or alternatively, transition to active ideation or suicidal behavior? Moreover, understanding what characteristics differentiate between those who do and do not transition to active ideation or behavior, as well as the determinants of the timing of these transitions, has potential value for risk stratification strategies. Suicidal behavior has been previously found most often to occur within a year of onset of suicidal ideation as a general construct (Nock et al., Reference Nock, Borges, Bromet, Alonso, Angermeyer, Beautrais and Williams2008a). Clarifying to what degree this holds true or differs for passive ideation specifically may be clinically informative regarding the potential length of the temporal window for intervening in the course from suicidal ideation to action.

Finally, several challenges in conducting prospective research in this area are notable. The low base rate of suicidal behavior introduces substantial challenges for achieving sufficient statistical power to conduct a meaningful analysis of predictors of suicide. Integrative data analysis may offer one solution to this challenge, by pooling data across multiple studies in order to answer questions about phenomena that require larger sample sizes (Hussong, Curran, & Bauer, Reference Hussong, Curran and Bauer2013). Further contributing to the challenges of research in this area is the length of time over which samples are followed. Given that suicidal behavior is a low-base-rate event, past studies have often utilized long follow-up periods in order to increase the likelihood of capturing these events. Studies of long-term risk are important for identifying who may be at risk for suicidal behaviors, but do not inform our understanding of when individuals are at greatest risk for suicide. Recent research has shifted toward greater emphasis on understanding short-term predictors of suicide risk, utilizing, for example, ecological momentary assessment and passive data collection methods, with the goal of identifying factors predicting the transition from suicidal ideation to behavior (Glenn, Cha, Kleiman, & Nock, Reference Glenn, Cha, Kleiman and Nock2017; Glenn & Nock, Reference Glenn and Nock2014).

In conclusion, the current review found the lifetime prevalence of passive ideation in the general population to be substantial. That this is clinically concerning is indicated by the high psychiatric comorbidity found in our analyses, the strong association with suicide attempts, and preliminary evidence of a comparably strong relation with suicide deaths. One group that emerged as being particularly at risk, and thus a priority for the development of screening and intervention protocols, is sexual minority individuals. The current findings are also suggestive of notable similarities between passive and active ideation, particularly in terms of psychiatric comorbidity and psychological and other characteristics traditionally associated with risk. Collectively, these findings are indicative of the need for greater focus on passive ideation in research and clinical contexts.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (RF1MH120830, R01MH101138, R01MH115905, and R21MH112055). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agency.

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.