Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a highly prevalent, burdensome, and heterogeneous mental health disorder. This heterogeneity presumably represents multiple causal pathways and consequently multiple therapeutic targets. The development of novel therapeutic agents would benefit from the identification of more homogeneous depression subtypes, which could be derived based on a triangulation of clinical phenotypes, risk factors and biology (Harald and Gordon, Reference Harald and Gordon2012). One such subtype is depression with atypical features.

Atypical depression (AD) is an intriguing clinical phenomenon that has been recognised since the late 1950s and has evolved as a syndrome of varying definitions (Davidson and Thase, Reference Davidson and Thase2007; Lojko and Rybakowski, Reference Lojko and Rybakowski2017). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th edition (DSM-5) criteria for AD requires mood reactivity and at least two of the following symptoms: increased appetite or weight gain, hypersomnia, leaden paralysis and interpersonal rejection sensitivity (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Whereas most clinical studies adopt the DSM criteria for AD, community studies tend to classify AD based purely on reversed neurovegetative symptoms (i.e. hypersomnia and increased appetite/weight gain) (Levitan et al., Reference Levitan, Lesage, Parikh, Goering and Kennedy1997; Matza et al., Reference Matza, Revicki, Davidson and Stewart2003; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Ng and Tsang2009), for a number of reasons. First, reversed neurovegetative symptoms are easier to operationalise in epidemiological studies than other DSM criteria for atypicality. Second, several studies have questioned the evidential support for the role of mood reactivity and interpersonal rejection sensitivity in the diagnosis of atypical depression (Benazzi, Reference Benazzi2002b; Parker and Thase, Reference Parker and Thase2007). Third, reversed neurovegetative symptoms were found to be highly specific (90.5%), and have good positive predictive value (86.1%) for DSM-defined AD (Benazzi, Reference Benazzi2002a). Fourth, research comparing AD based on reversed neurovegetative symptoms with AD based on the full DSM criteria found similar associations with a range of sociodemographic characteristics and comorbidities (Benazzi, Reference Benazzi2002a). Lastly, AD based on reversed neurovegetative symptoms may be more strongly associated with external validating characteristics of AD (e.g. gender, bipolar disorder, family history of mania) than other atypical symptoms of depression (Angst et al., Reference Angst, Gamma, Benazzi, Silverstein, Ajdacic-Gross, Eich and Rossler2006).

There is growing interest in understanding the epidemiological, neurobiological, and genetic underpinnings of AD (Lojko and Rybakowski, Reference Lojko and Rybakowski2017). Evidence from clinical and community-based studies suggest differences between AD and nonAD in sociodemographic factors, depression features, comorbidities, biomarkers, polygenic risk, and treatment response. Atypical depression is more strongly associated with female gender (Matza et al., Reference Matza, Revicki, Davidson and Stewart2003; Angst et al., Reference Angst, Gamma, Benazzi, Ajdacic and Rossler2007; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Ng and Tsang2009), younger age of depression onset, greater symptom severity, more depression episodes, greater functional impairment (Stewart et al., Reference Stewart, McGrath, Rabkin and Quitkin1993; Nierenberg et al., Reference Nierenberg, Alpert, Pava, Rosenbaum and Fava1998; Agosti and Stewart, Reference Agosti and Stewart2001; Blanco et al., Reference Blanco, Vesga-Lopez, Stewart, Liu, Grant and Hasin2012), and more adverse life events (Matza et al., Reference Matza, Revicki, Davidson and Stewart2003; Withers et al., Reference Withers, Tarasoff and Stewart2013). AD is also associated with higher rates of psychiatric comorbidity such as bipolar, anxiety, addictions, binge eating and psychotic disorders (Agosti and Stewart, Reference Agosti and Stewart2001; Angst et al., Reference Angst, Gamma, Sellaro, Zhang and Merikangas2002; McGinn et al., Reference McGinn, Asnis, Suchday and Kaplan2005; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Ng and Tsang2009; Blanco et al., Reference Blanco, Vesga-Lopez, Stewart, Liu, Grant and Hasin2012), higher Body Mass Index (BMI) (Lasserre et al., Reference Lasserre, Glaus, Vandeleur, Marques-Vidal, Vaucher, Bastardot, Waeber, Vollenweider and Preisig2014) as well as polygenic risk scores for BMI and triglycerides (Milaneschi et al., Reference Milaneschi, Lamers, Peyrot, Abdellaoui, Willemsen, Hottenga, Jansen, Mbarek, Dehghan, Lu, Boomsma and Penninx2016), higher rates of metabolic syndrome, inflammation, and leptin dysregulation (Lamers et al., Reference Lamers, Beekman, van Hemert, Schoevers and Penninx2016a; Lamers et al., Reference Lamers, Vogelzangs, Merikangas, de Jonge, Beekman and Penninx2013; Milaneschi et al., Reference Milaneschi, Lamers, Bot, Drent and Penninx2017a), and greater heritability than nonAD (Lamers et al., Reference Lamers, Cui, Hickie, Roca, Machado-Vieira, Zarate and Merikangas2016b). Existing evidence is limited by the use of different comparison groups across studies: non-atypical depression (i.e. depression without reversed neurovegetative symptoms) (e.g. Agosti and Stewart, Reference Agosti and Stewart2001; Matza et al., Reference Matza, Revicki, Davidson and Stewart2003; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Ng and Tsang2009), typical depression with both neurovegetative symptoms (i.e. hyposomnia and reduced appetite and/or weight loss) (e.g. Levitan et al., Reference Levitan, Lesage, Parikh, Goering and Kennedy1997; Blanco et al., Reference Blanco, Vesga-Lopez, Stewart, Liu, Grant and Hasin2012) or just one neurovegetative symptom (i.e. appetite loss/weight loss) (e.g. Milaneschi et al., Reference Milaneschi, Lamers, Peyrot, Abdellaoui, Willemsen, Hottenga, Jansen, Mbarek, Dehghan, Lu, Boomsma and Penninx2016), or melancholic depression (e.g. Angst et al., Reference Angst, Gamma, Benazzi, Ajdacic and Rossler2007; Lamers et al., Reference Lamers, Beekman, van Hemert, Schoevers and Penninx2016a).

An important proportion of persons who experience common mental health disorders such as depression do not receive clinical assessment or treatment. Conclusions from clinical studies on depression subtypes suffer from poor external validity and are not powered enough to consider multiple outcomes. Community-based psychiatric epidemiology studies are needed to help characterize depression phenotypes based on lifetime self-reported symptoms. Existing evidence from studies that examined atypical depression with reversed neurovegetative is limited by small sample size (Levitan et al., Reference Levitan, Lesage, Parikh, Goering and Kennedy1997; Benazzi, Reference Benazzi2002a; Matza et al., Reference Matza, Revicki, Davidson and Stewart2003), a focus on current or recent rather than lifetime depression episodes (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Ng and Tsang2009), the use of different comparison groups, and data availability on a relatively limited number of comorbidities and correlates of atypical depression.

The UK Biobank MHQ is one of the largest mental health surveys ever conducted among middle-aged and older adults (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Coleman, Adams, Allen, Breen, Cullen, Dickens, Fox, Graham, Holliday, Howard, John, Lee, McCabe, McIntosh, Pearsall, Smith, Sudlow, Ward, Zammit and Hotopf2018). Given the diversity of mental health measures and linkages to UKB baseline assessments, this study offers the opportunity to replicate and extend evidence on the sociodemographic, clinical, lifestyle, and comorbidity profile of persons with lifetime AD characterized by reversed neurovegetative symptoms compared to those with nonAD, or those with typical neurovegetative symptoms. This foundational work could form the basis for exploring biomarker and genetic correlates of atypical depression in the UK Biobank, and could further guide intervention approaches.

Method

Subjects

The UK Biobank is a well-characterized cohort of over half a million participants aged 40–69 at baseline (2007–2010), providing the potential for a detailed examination of the interplay between genetic, biological, lifestyle, and environmental factors and the risk of physical and mental health disorders, which is further enhanced by planned follow-up assessments and linkages to routine healthcare records. A comprehensive description of the UK Biobank cohort, study design, and assessments has been published elsewhere (Sudlow et al., Reference Sudlow, Gallacher, Allen, Beral, Burton, Danesh, Downey, Elliott, Green, Landray, Liu, Matthews, Ong, Pell, Silman, Young, Sprosen, Peakman and Collins2015). An online Mental Health Questionnaire (MHQ) was developed and implemented into the UK Biobank web questionnaire platform with the aim to identify mental health disorders either based on self-reported symptoms matching psychiatric diagnostic criteria or based on other self-reported psychiatric diagnosis (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Coleman, Adams, Allen, Breen, Cullen, Dickens, Fox, Graham, Holliday, Howard, John, Lee, McCabe, McIntosh, Pearsall, Smith, Sudlow, Ward, Zammit and Hotopf2018). Participants who volunteered to take part in the study had higher socioeconomic status, healthier lifestyle and fewer health conditions than the general population (Fry et al., Reference Fry, Littlejohns, Sudlow, Doherty, Adamska, Sprosen, Collins and Allen2017; Davis et al., Reference Davis, Coleman, Adams, Allen, Breen, Cullen, Dickens, Fox, Graham, Holliday, Howard, John, Lee, McCabe, McIntosh, Pearsall, Smith, Sudlow, Ward, Zammit and Hotopf2018). Out of 503 328 participants who completed the baseline UK Biobank assessments, 339 092 (67.4%) participants received an email invitation to complete the MHQ, with 157 366 of those emailed (46.4%) responding by August 2017. Approximately 37 434 (23.8%) of those who completed the MHQ met the criteria for a lifetime diagnosis of MDD and were included in the current study.

Measures

Data were accessed through standard UKB procedures (access number 34 553, Matthew Hotopf and collaborators) in July 2018. Case and control criteria for psychiatric disorders are presented in online Supplementary Table S7 (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Coleman, Adams, Allen, Breen, Cullen, Dickens, Fox, Graham, Holliday, Howard, John, Lee, McCabe, McIntosh, Pearsall, Smith, Sudlow, Ward, Zammit and Hotopf2018). All other variables were assessed using specific sets of questions and possible answers as detailed in online Supplementary Table S6. All information on lifetime mental health symptoms, psychiatric diagnoses, and adverse life events (i.e. childhood, adulthood and catastrophic trauma) was collected during the MHQ assessments conducted in 2016–2017. Data on sociodemographic characteristics (i.e. age, gender, education, income, house ownership), lifestyle factors (i.e. smoking, physical activity, loneliness, social isolation), and physical comorbidities (i.e. longstanding illness, CVD, BMI, metabolic syndrome) were collected during the baseline UK Biobank assessments between 2006 and 2010.

Lifetime MDD was assessed using the Composite International Diagnostic Interview Short Form (CIDI-SF) (Kessler and Ustun, Reference Kessler and Ustun2004) and it required at least one core symptom of depression (i.e. persistent sadness or loss of interest) and at least four additional symptoms (i.e. tired or low energy, weight change, sleep change, trouble concentrating, feeling worthless, thinking about death), for a period of at least 2 weeks, representing a change from usual and associated with some or a lot of impairment. The CIDI-SF has been designed and shown to have good comparability with the full WHO Composite International Diagnostic Interview, although it shares with many screening tools a lack of specificity in community samples. Previous studies suggest that CIDI-SF has good sensitivity (89.6%) and specificity (93.9%), with 93.2% of respondents being classified as probable MDD cases on both the CIDI-SF and the full CIDI interview when these instruments were administered as part of the same survey (Kessler and Ustun, Reference Kessler and Ustun2004). However, independent validation studies reported that CIDI-SF is highly sensitive but not very specific (i.e. identifies a high number of false positives), and recommended that CIDI-SF would be a useful general screening measure for depression, but not a highly accurate tool for prevalence estimates (Patten, Reference Patten1997; Sunderland et al., Reference Sunderland, Andrews, Slade and Peters2011). Online CIDI-SF screening for recurrent MDD had a 81.8% validation rate by the SCID interview, whereas the validation rate for single episode MDD was 87.6% (Levinson et al., Reference Levinson, Potash, Mostafavi, Battle, Zhu and Weissman2017). The lifetime version of the CIDI-SF asked about symptoms experienced during the worst ever depression episode. Consistent with previous studies (Benazzi, Reference Benazzi2002a; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Ng and Tsang2009; Blanco et al., Reference Blanco, Vesga-Lopez, Stewart, Liu, Grant and Hasin2012), the presence of reversed neurovegetative symptoms was used to differentiate between AD and nonAD. Participants reporting both hypersomnia and weight gain were classified as AD cases (N = 2305), and the others classified as nonAD cases (N = 35 129).

Diagnostic criteria based on self-report questionnaires were also evaluated for generalised anxiety disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and bipolar affective disorder (i.e. wider bipolar disorder, bipolar I disorder, and bipolar II disorder), as defined in online Supplementary Table S7. Of note, there is limited agreement about the definition of bipolar II disorder in MHQ. Whereas the DSM-IV criteria require symptoms present for minimum 4 days, the MHQ criteria require symptoms present for at least 1 week, so it could be predicted to miss some cases. Also, given that bipolar II disorder does not require disruption from symptoms, self-reported symptoms may reflect normal emotional experiences, resulting in an increased number of false positives (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Coleman, Adams, Allen, Breen, Cullen, Dickens, Fox, Graham, Holliday, Howard, John, Lee, McCabe, McIntosh, Pearsall, Smith, Sudlow, Ward, Zammit and Hotopf2018). Other psychiatric comorbidities were defined by asking participants if they have ever been diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder by a mental health professional, including psychotic disorders (i.e. schizophrenia, other psychosis), anxiety disorders (i.e. panic attacks, agoraphobia, social phobia), obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), eating disorders (i.e. anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge-eating disorder), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, autism spectrum disorder and personality disorders. Participants also self-reported any lifetime addiction (including substances and behaviours), substance dependence (including medication and illicit or recreational drugs), and alcohol dependence. They also reported a history of self-harm, with or without suicide intent (see online Supplementary Table S6).

Participants were classified as having metabolic syndrome if they had a waist circumference ⩾102 cm or above for males and ⩾88 cm for females, and a combination of any two of the following: (1) hypertension defined as (a) average systolic blood pressure ⩾140 over three assessment occasions and/or (b) average diastolic blood pressure ⩾90 over three assessment occasions, and/or (c) hypertension medication prescription, and/or (d) a clinical diagnosis of hypertension according to participant self-report; (2) diabetes defined as (a) diabetes medication prescription; (b) a clinical diagnosis of diabetes according to participant self-report; and (3) hypercholesterolemia defined as (a) statins medication prescription; (b) a clinical diagnosis of hypercholesterolemia according to participant self-report.

Statistical analysis

Univariate logistic regression models were conducted to examine differences between persons with AD (i.e. meeting the criteria for MDD + hypersomnia and weight gain) and persons with nonAD (i.e. meeting the criteria for MDD without hypersomnia and weight gain) in sociodemographic factors (i.e. age, gender, education, income, house ownership). Multivariable logistic regression models were used to examine differences between nonAD and AD in lifestyle factors, lifetime adversities, depression features, and comorbidities, controlling for age and gender, and then also for socioeconomic factors. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to compare persons with AD (as defined above) and those with typical vegetative symptoms (i.e. meeting the criteria for MDD + reporting weight loss, and either waking up too early or trouble falling asleep).

Results

Tetrachoric correlations between CIDI-SF depressive symptoms among persons with lifetime probable MDD are presented in online Supplementary Table S5.

Prevalence of depression subtypes and associations with sociodemographic factors

The AD group (N = 2305) had a mean age of 59.8 years old and 75% were female, whereas the nonAD group (N = 35 129) had a mean age of 62.4 years old and 68% were female. Persons with AD had lower income, and they were less likely to own a mortgage or the outright for their home than persons with nonAD (see Table 1).

Table 1. Sociodemographic differences between persons with atypical depression and those with non-atypical depression

Depression course

The mean age of depression onset was 31.9 in the AD group and 35.5 in the nonAD group. Compared to persons with nonAD those with AD experienced more severe, recurrent, and lengthy depression episodes. For instance, 24% of persons with AD experienced a depression episode lasting over 2 years compared to 13% of persons with nonAD; 39% of persons with AD experienced a severe depression episode compared to 14% of persons with nonAD (i.e. depression was considered severe when all eight CIDI-SF symptoms were endorsed). Persons with AD were more likely to seek professional help for depression (see Table 2).

Table 2. Differences in depression age of onset, severity, recurrence, episode duration, and help seeking between persons with atypical depression and those with non-atypical depression

Note: Models are adjusted for age and gender

Lifestyle factors and lifetime adversities

Persons with atypical depression were more likely to be smokers, they reported higher rates of social isolation and loneliness, and lower rates of moderate physical activity. Moreover, they were more likely to experience a variety of adverse events over their life course, including emotional, physical and sexual abuse during childhood and adulthood, financial difficulties and catastrophic trauma (see Table 3).

Table 3. Differences in lifestyle factors and adverse life events between persons with atypical depression and those with non-atypical depression

Note: Models are adjusted for age and gender. Catastrophic trauma is defined being attacked, mugged, robbed, exposed to violent crime, sexual assault, serious accidents, life-threatening illness, combat or war, violent death

Psychiatric comorbidities

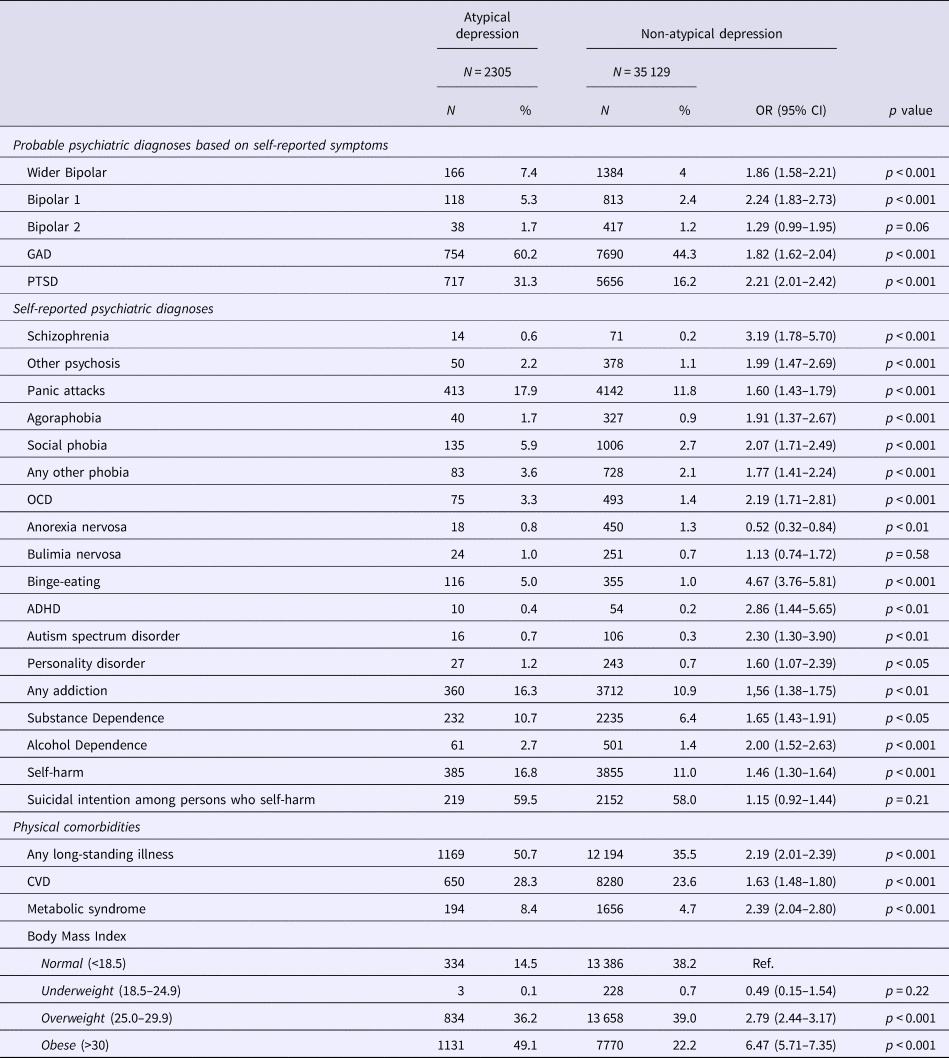

Persons with AD were more likely to experience a probable lifetime psychiatric disorder of GAD, bipolar I and wider bipolar disorder (but not bipolar II), and they were more likely to meet the criteria for PTSD. Also, persons with AD were more likely to self-report a lifetime psychiatric diagnosis, including schizophrenia, agoraphobia, social phobia, panic attacks, OCD, autism spectrum disorders, ADHD, substance and alcohol dependence, personality disorders, and self-harm. The odds of binge eating disorder were 4.6 higher among persons with AD compared to those with nonAD. Persons with AD had lower rates of anorexia and similar rates of bulimia as those with nonAD (see Table 4).

Table 4. Differences in psychiatric and physical comorbidities between persons with atypical depression and those with non-atypical depression

Note: Models are adjusted for age and gender.

Physical comorbidities

Persons with AD had higher odds of long-standing illness, CVD, and metabolic syndrome; they scored higher on each of the components of the metabolic syndrome: diabetes (OR = 2.32, 95% CI 1.94–2.78), hypertension (OR = 1.65, 95% CI 1.49–1.82) and hypercholesterolemia (OR = 1.49, 95% CI 1.30–1.71). BMI scores were significantly higher among persons with AD (Mean = 30.7, s.d. = 5.9) compared to those with nonAD (Mean = 27.0, s.d. = 4.9), with a greater proportion of overweight and obese persons in the AD group (see Table 4).

Sensitivity analyses

All differences between AD and nonAD in depression features, sociodemographic and lifestyle factors, lifetime adversities, psychiatric and physical comorbidities remained statistically significant after accounting for socioeconomic status (i.e. income, house ownership, education), except for personality disorders and smoking status.

The requirement of participants in the AD group to have two specific symptoms (hypersomnia and weight gain) may have resulted in the selection of a more severe sample, since severity in this definition is defined by number of symptoms. Therefore, we conducted a set of sensitivity analyses that compared persons with AD (i.e. hypersomnia and weight gain) with those meeting the criteria for depression with typical neurovegetative symptoms (i.e. weight loss and hyposomnia: waking too early or trouble falling asleep), thereby requiring two specific symptoms in both samples. Among depressed persons with typical neurovegetative symptoms 24% had severe depression, v. 39% of AD persons. These sensitivity analyses revealed a similar pattern of findings (in terms of direction, magnitude, and statistical significance of the effect) as the main analyses using nonAD as the comparison group, except for gender differences and personality disorder differences which were no longer statistically significant (see online Supplementary Tables S1–S4).

Discussion

This study ascertains AD based on reversed neurovegetative symptoms as a valid entity in a large community-based sample, and it informs on differences between AD and nonAD in terms of sociodemographic, lifestyle, and clinical characteristics, lifetime psychiatric and physical comorbidities. These findings highlight the clinical and public health significance of the AD classifier.

The previously reported prevalence of AD based on reversed neurovegetative symptoms was in the range of 11–16% (Horwath et al., Reference Horwath, Johnson, Weissman and Hornig1992; Levitan et al., Reference Levitan, Lesage, Parikh, Goering and Kennedy1997). In our study about 6.5% (N = 2305) of persons with MDD met the criteria for AD. Given that the UK Biobank sample is not representative for the general population (i.e. healthy volunteer effect) these results should not be interpreted as estimates of AD prevalence in the wider community, but rather as proportions within the sample. Building on prior evidence, our findings suggest that persons with AD have a younger age of depression onset (Matza et al., Reference Matza, Revicki, Davidson and Stewart2003; Novick et al., Reference Novick, Stewart, Wisniewski, Cook, Manev, Nierenberg, Rosenbaum, Shores-Wilson, Balasubramani, Biggs, Zisook and Rush2005; Thase, Reference Thase2007; Blanco et al., Reference Blanco, Vesga-Lopez, Stewart, Liu, Grant and Hasin2012; Koyuncu et al., Reference Koyuncu, Ertekin, Ertekin, Binbay, Yuksel, Deveci and Tukel2015), longer (Angst et al., Reference Angst, Gamma, Sellaro, Zhang and Merikangas2002; Posternak and Zimmerman, Reference Posternak and Zimmerman2002), more severe (Novick et al., Reference Novick, Stewart, Wisniewski, Cook, Manev, Nierenberg, Rosenbaum, Shores-Wilson, Balasubramani, Biggs, Zisook and Rush2005; Blanco et al., Reference Blanco, Vesga-Lopez, Stewart, Liu, Grant and Hasin2012), and recurrent episodes (Blanco et al., Reference Blanco, Vesga-Lopez, Stewart, Liu, Grant and Hasin2012; Koyuncu et al., Reference Koyuncu, Ertekin, Ertekin, Binbay, Yuksel, Deveci and Tukel2015), and higher help seeking rates (Matza et al., Reference Matza, Revicki, Davidson and Stewart2003; Angst et al., Reference Angst, Gamma, Benazzi, Silverstein, Ajdacic-Gross, Eich and Rossler2006; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Ng and Tsang2009) compared to persons with nonAD.

Consistent with previous evidence, we found that depression with atypical features was associated with female gender (Agosti and Stewart, Reference Agosti and Stewart2001; Benazzi, Reference Benazzi2002a; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Ng and Tsang2009; Blanco et al., Reference Blanco, Vesga-Lopez, Stewart, Liu, Grant and Hasin2012) and with unhealthier behaviours, such as reduced physical activity (Glaus et al., Reference Glaus, Vandeleur, Gholam-Rezaee, Castelao, Perrin, Rothen, Bovet, Marques-Vidal, von Kanel, Merikangas, Mooser, Waterworth, Waeber, Vollenweider and Preisig2013), social isolation (Agosti and Stewart, Reference Agosti and Stewart2001), and smoking. Previously, Koyuncu et al. (Reference Koyuncu, Ertekin, Ertekin, Binbay, Yuksel, Deveci and Tukel2015) found higher rates of social anxiety and avoidance among individual with AD features. These findings are not surprising given that hypersensitivity to criticism or rejection is a characteristic feature of AD which can lead individuals to avoid interpersonal activity and social situations. Consistent with prior reports (Blanco et al., Reference Blanco, Vesga-Lopez, Stewart, Liu, Grant and Hasin2012), we found that persons with AD were more likely to experience socio-economic disadvantage than persons with nonAD. Previously, childhood trauma, in the form of physical or sexual abuse, was associated with the reversed neurovegetative symptoms of AD (Matza et al., Reference Matza, Revicki, Davidson and Stewart2003). Our findings add to the existing literature by showing that AD is associated with a range of emotional, physical, sexual, financial and catastrophic adversities across the lifespan.

The diversity of mental health assessments in the MHQ offered the opportunity to examine associations between AD and a wide range of lifetime psychiatric comorbidities. Our findings on psychiatric comorbidities are consistent with a large community-based study on lifetime atypical depression conducted in the United States (Blanco et al., Reference Blanco, Vesga-Lopez, Stewart, Liu, Grant and Hasin2012). We found that persons with AD had higher rates of bipolar I and wider bipolar disorder than those with nonAD, but differences in bipolar II disorder were only marginally significant. An association between AD and bipolar I but not bipolar II was previously reported by Blanco et al. (Reference Blanco, Vesga-Lopez, Stewart, Liu, Grant and Hasin2012), but most existing evidence supports a strong association between AD and bipolar II disorder (Agosti and Stewart, Reference Agosti and Stewart2001; Angst et al., Reference Angst, Gamma, Sellaro, Zhang and Merikangas2002; Benazzi, Reference Benazzi2002a; Akiskal and Benazzi, Reference Akiskal and Benazzi2005; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Ng and Tsang2009). The failure to replicate this finding in our study may be due to the arguable definition of bipolar II disorder in the MHQ (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Coleman, Adams, Allen, Breen, Cullen, Dickens, Fox, Graham, Holliday, Howard, John, Lee, McCabe, McIntosh, Pearsall, Smith, Sudlow, Ward, Zammit and Hotopf2018) (see online Supplementary Table S7). Our findings are consistent with prior evidence suggesting higher rates of anxiety disorders (i.e. generalised anxiety, panic attacks, social phobia, agoraphobia) (Horwath et al., Reference Horwath, Johnson, Weissman and Hornig1992; Sullivan et al., Reference Sullivan, Kessler and Kendler1998; Angst et al., Reference Angst, Gamma, Sellaro, Zhang and Merikangas2002; Matza et al., Reference Matza, Revicki, Davidson and Stewart2003; Novick et al., Reference Novick, Stewart, Wisniewski, Cook, Manev, Nierenberg, Rosenbaum, Shores-Wilson, Balasubramani, Biggs, Zisook and Rush2005; Blanco et al., Reference Blanco, Vesga-Lopez, Stewart, Liu, Grant and Hasin2012; Koyuncu et al., Reference Koyuncu, Ertekin, Ertekin, Binbay, Yuksel, Deveci and Tukel2015), OCD (Perugi et al., Reference Perugi, Akiskal, Lattanzi, Cecconi, Mastrocinque, Patronelli, Vignoli and Bemi1998), psychotic disorders (Blanco et al., Reference Blanco, Vesga-Lopez, Stewart, Liu, Grant and Hasin2012), binge eating (Angst et al., Reference Angst, Gamma, Sellaro, Zhang and Merikangas2002; Angst et al., Reference Angst, Gamma, Benazzi, Silverstein, Ajdacic-Gross, Eich and Rossler2006), substance and alcohol dependence (Blanco et al., Reference Blanco, Vesga-Lopez, Stewart, Liu, Grant and Hasin2012), and personality disorders (McGinn et al., Reference McGinn, Asnis, Suchday and Kaplan2005) among persons with AD. Additionally, we found that persons with AD had higher rates of ADHD, autism, and self-harm, but they were not more likely than persons with nonAD to self-harm with suicide intent. A study conducted in Hong Kong reported a trend for higher rates of suicidal ideation and suicidal attempt in AD (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Ng and Tsang2009).

The association between MDD and obesity is supported by widespread evidence, including findings from a recent UK Biobank study (Ul-Haq et al., Reference Ul-Haq, Smith, Nicholl, Cullen, Martin, Gill, Evans, Roberts, Deary, Gallacher, Hotopf, Craddock, Mackay and Pell2014). Emerging evidence suggests higher rates of obesity and metabolic syndrome among persons meeting the full DSM-IV criteria for atypical depression (Lasserre et al., Reference Lasserre, Glaus, Vandeleur, Marques-Vidal, Vaucher, Bastardot, Waeber, Vollenweider and Preisig2014) and among those meeting only the hyperphagia and weight gain criteria (Lamers et al., Reference Lamers, Vogelzangs, Merikangas, de Jonge, Beekman and Penninx2013). Recent evidence also suggests a genetic overlap between obesity and an AD subtype characterized by increased appetite and weight gain (Milaneschi et al., Reference Milaneschi, Lamers, Peyrot, Baune, Breen, Dehghan, Forstner, Grabe, Homuth, Kan, Lewis, Mullins, Nauck, Pistis, Preisig, Rivera, Rietschel, Streit, Strohmaier, Teumer, Van der Auwera, Wray, Boomsma and Penninx2017b). We found that among persons with AD characterized by reversed neurovegetative symptoms 49% were obese (BMI ⩾ 30) and 36% were overweight (BMI ⩾ 25), whereas among nonAD persons 22% were obese and 39% were overweight. Biological theories propose that leptin dysregulation and inflammation underlie the association between obesity and atypical depression, whereas psychological theories suggest that the interpersonal rejection sensitivity that is characteristic to AD is accompanied by emotional dysregulation mechanisms and self-consolatory behaviours such as comfort eating (for a review see Lojko and Rybakowski, Reference Lojko and Rybakowski2017). With regard to the association between atypical depression and CVD, prior evidence is mixed, with some findings suggesting a higher CVD incidence among AD persons with reversed neurovegetative symptoms (Case et al., Reference Case, Sawhney and Stewart2018), whereas other reports support and association between atypical depression and cardiovascular risk factors but not CVD diagnosis (Niranjan et al., Reference Niranjan, Corujo, Ziegelstein and Nwulia2012). Our findings confirm higher rates of CVD among AD persons. It should be noted that information on physical comorbidities was collected during the UK Biobank baseline assessments conducted approximately 7 years before the MHQ. The relation between depression and comorbidities such as obesity, metabolic syndrome and CVD is likely multifaceted and bidirectional. Given that our study focused on lifetime depression it was not possible to determine whether physical disorders occurred before or after the atypical depression episode, hence not allowing inferences about the direction of the effect.

Finally, it is worth noting that the same pattern of results emerged when comparing persons with AD (hypersomnia and weight gain) with those reporting the opposite/typical neurovegetative symptoms (hyposomnia and weight loss), suggesting that the observed findings are not simply attributable to the selection of more severe depression cases in the AD group.

Strengths and limitations

The current study based on the UK Biobank MHQ dataset provided a unique opportunity to identify differences between typical and atypical depression in illness course, sociodemographic and lifestyle factors, adverse life events and comorbidities in a large community sample of middle aged and older adults. However, there are also a number of limitations. First, the UK Biobank is not representative for the overall population as there is a degree of ‘healthy volunteer’ selection bias, with higher participation rates among females, older, better educated, less deprived, and healthier participants than the general population (Fry et al., Reference Fry, Littlejohns, Sudlow, Doherty, Adamska, Sprosen, Collins and Allen2017). Furthermore, participants who completed the MHQ have higher educational and occupational attainment, and lower rates of longstanding illness, disability and smoking than the overall UK Biobank cohort and the general population (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Coleman, Adams, Allen, Breen, Cullen, Dickens, Fox, Graham, Holliday, Howard, John, Lee, McCabe, McIntosh, Pearsall, Smith, Sudlow, Ward, Zammit and Hotopf2018). It has been previously shown that non-response to MHQ is weakly related to depression status, with 20.3% of the MHQ respondents v. 23.6% of the MHQ non-respondents reporting feeling depressed during the last 2 weeks preceding the baseline UKB assessment (conducted approximately 7 years before the MHQ), and 5.2% of the MHQ respondents v. 7.1% of the MHQ non-respondents reporting a lifetime medical diagnosis of depression during the baseline UK Biobank assessments (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Coleman, Adams, Allen, Breen, Cullen, Dickens, Fox, Graham, Holliday, Howard, John, Lee, McCabe, McIntosh, Pearsall, Smith, Sudlow, Ward, Zammit and Hotopf2018). It was not possible to compare non-response rates between the AD and the nonAD group because baseline UK Biobank assessments did not include questions allowing a characterization of depression subtypes. It is possible that the healthy volunteer selection bias in the UK Biobank MHQ may have resulted in an underestimation of the prevalence of AD in our sample, given the higher depression severity among AD patients and the fact that severely depressed persons were less likely to complete the MHQ. Second, due to the cross-sectional nature of this study, our findings do not allow to determine whether life events and comorbidities occurred before, during or after the typical v. atypical depression episode. Moreover, it was not possible to determine whether participants experienced lifetime fluctuations between typical and atypical depression episodes as suggested by previous reports (Levitan et al., Reference Levitan, Lesage, Parikh, Goering and Kennedy1997; Angst et al., Reference Angst, Gamma, Benazzi, Ajdacic and Rossler2007). Third, psychiatric conditions were assessed using self-reported symptoms and self-reported diagnosis, so they represent probable, rather than definitive, clinical diagnoses (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Coleman, Adams, Allen, Breen, Cullen, Dickens, Fox, Graham, Holliday, Howard, John, Lee, McCabe, McIntosh, Pearsall, Smith, Sudlow, Ward, Zammit and Hotopf2018). CIDI-SF does not contain questions assessing appetite changes, but only weight changes. We had no specific cut-off points to quantify the weight gain or the number of hours of sleep per night during the worst depression episode. Therefore, we cannot exclude the possibility that self-reported symptoms may be subject to recall bias or may be affected by other medical conditions. Finally, our assessments did not capture other atypical symptoms such as leaden paralysis, interpersonal rejection sensitivity or mood reactivity. Nevertheless, our findings based on a definition of atypical depression characterized by reversed neurovegetative symptoms are remarkably consistent with prior evidence from both clinical and community-based studies.

Conclusions and implications

The symptom heterogeneity of depression, in conjunction with etiological and methodological heterogeneity, hinders progress in the diagnosis, prognosis and treatment of depression. A better characterization of the AD subtype in terms of symptom profile, clinical course, neurobiology and comorbidities could inform personalized medicine approaches (Korte et al., Reference Korte, Prins, Krajnc, Hendriksen, Oosting, Westphal, Korte-Bouws and Olivier2015). Our findings suggest that criteria such as early age of onset, chronicity, and recurrence should be considered as part of the clinical picture of AD. The pernicious course of AD and the high psychiatric comorbidity profile have important implications for health care utilization and costs. In clinical practice, focusing on the identification of atypical features could inform prognosis, and treatment planning. Future research should determine to what extent the early identification and treatment of atypical depression symptoms may prevent or delay the onset of physical comorbidities. Forthcoming availability of biomarker data in the UK Biobank will provide the opportunity to further examine metabolic and inflammatory biomarkers in atypical depression. The high rate of obesity and metabolic syndrome among atypically depressed persons could have implications for treatment selection (i.e. antidepressant treatment that does not influence weight gain). Patients with different/opposite depression symptoms likely have different neurobiological disturbances and could benefit from better tailored therapeutic approaches. Although findings on differential treatment response are largely controversial (Harald and Gordon, Reference Harald and Gordon2012), recent evidence suggests larger treatment response to exercise in AD compared to nonAD (Rethorst et al., Reference Rethorst, Tu, Carmody, Greer and Trivedi2016), a superior effect of cognitive therapy compared to paroxetine treatment in reducing atypical-vegetative symptoms (Fournier et al., Reference Fournier, DeRubeis, Hollon, Gallop, Shelton and Amsterdam2013), and the potential of pharmacotherapy and cognitive therapy continuation to reduce relapse rates among persons with AD (Jarrett et al., Reference Jarrett, Kraft, Schaffer, Witt-Browder, Risser, Atkins and Doyle2000). Clinical trials should further determine the effectiveness of lifestyle interventions and therapeutic agents targeting metabolic and inflammatory pathways in AD. This knowledge could inform treatment guidelines and facilitate a better management of persons with atypical symptoms of depression.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291719001004

Author ORCIDs

Anamaria Brailean, 0000-0002-6334-7349

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr Gerome Breen and Dr Jonathan Coleman from the Social Genetic & Developmental Psychiatry Department at IoPPN, King's College London for their assistance with data coding and management.

Financial support

This paper represents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King's College London. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Conflict of interest

None.