Introduction

The boundary between borderline personality disorder (BPD) and bipolar affective disorder (BD) is a source of persistent clinical uncertainty, which arises through the overlap of their acute clinical presentations. Specifically, both borderline crises and manic (or mixed) bipolar episodes are characterized by heightened irritability, emotional lability, chronic depressive symptoms and impulsive behaviours. Accurate differentiation remains important because, while BPD and BD are relatively common diagnoses, with comparable prevalences of between 4% and 6% in the adult population (Angst, Reference Angst1998; Grant et al. Reference Grant, Chou, Goldstein, Huang, Stinson, Saha, Smith, Dawson, Pulay, Pickering and Ruan2008), their treatment recommendations are currently highly polarized. Whether the evidence justifies such polarization is perhaps questionable, but the recommendations are clear. Thus, consensus guidelines recommend long-term treatment with mood stabilizers for BD (Goodwin and Consensus Group of the British Association for Psychopharmacology, Reference Goodwin2009) and psychotherapy for BPD (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2009).

By contrast, other sources of evidence suggest that BPD belongs to the spectrum of mood-related disorders (Akiskal et al. Reference Akiskal, Chen, Davis, Puzantian, Kashgarian and Bolinger1985; Atre-Vaidya & Hussain, Reference Atre-Vaidya and Hussain1999; Deltito et al. Reference Deltito, Martin, Riefkohl, Austria, Kissilenko and Corless2001). The broadening of the bipolar diagnosis to include a spectrum of poorly defined conditions has added to the plausibility of this idea, with further support provided by the high degree of co-morbidity between BPD and BD diagnoses: 15% of BD-I and II cases in community surveys satisfy the criteria for BPD and vice versa (Lenzenweger et al. Reference Lenzenweger, Lane, Loranger and Kessler2007), and the still higher co-morbidity reported in clinically representative samples (Carpenter et al. Reference Carpenter, Clarkin, Glick and Wilner1995; Kay et al. Reference Kay, Altshuler, Ventura and Mintz1999; Brieger et al. Reference Brieger, Ehrt and Marneros2003). Finally, individuals with BD and individuals with BPD both exhibit impairments in the performance of standard neuropsychological tests of mnemonic and executive function (Adida et al. Reference Adida, Jollant, Clark, Besnier, Guillaume, Kaladjian, Mazzola-Pomietto, Jeanningros, Goodwin, Azorin and Courtet2011; Schuermann et al. Reference Schuermann, Kathmann, Stiglmayr, Renneberg and Endrass2011; Bourne et al. Reference Bourne, Aydemir, Balanza-Martinez, Bora, Brissos, Cavanagh, Clark, Cubukcuoglu, Dias, Dittmann, Ferrier, Fleck, Frangou, Gallagher, Jones, Kieseppa, Martinez-Aran, Melle, Moore, Mur, Pfennig, Raust, Senturk, Simonsen, Smith, Bio, Soeiro-de-Souza, Stoddart, Sundet, Szoke, Thompson, Torrent, Zalla, Craddock, Andreassen, Leboyer, Vieta, Bauer, Worhunsky, Tzagarakis, Rogers, Geddes and Goodwin2013) although there are no published investigations that have compared the two diagnoses directly.

In this experiment, we take a different approach by investigating the preliminary hypothesis that BPD and BD can exhibit divergent behaviours in the context of social exchanges. Mood instability in BPD is most powerfully expressed in the context of disrupted interpersonal relationships. Such interpersonal difficulties have been linked to impairments in decoding social signals, such as facial expression (Minzenberg et al. Reference Minzenberg, Poole and Vinogradov2006), or deeper problems in trusting the motives and actions of others (Lieb et al. Reference Lieb, Zanarini, Schmahl, Linehan and Bohus2004; Fonagy & Bateman, Reference Fonagy and Bateman2006). By contrast, mood instability in BD is traditionally seen as primary, and not attributed to comparable social impairments because social and occupational function can be high (Kusznir et al. Reference Kusznir, Cooke and Young2000). Therefore, we hypothesized that, despite the common breakdown of relationships and professional position in BD, and problems with affective decision making (Adida et al. Reference Adida, Jollant, Clark, Besnier, Guillaume, Kaladjian, Mazzola-Pomietto, Jeanningros, Goodwin, Azorin and Courtet2011), emotion recognition (Martino et al. Reference Martino, Strejilevich, Fassi, Marengo and Igoa2011) and theory of mind (Martino et al. Reference Martino, Strejilevich, Fassi, Marengo and Igoa2011), difficulties with cooperative behaviour in a laboratory setting would be more marked in individuals with BPD than individuals with BD and controls. In other words, disrupted social exchanges may be a primary locus of BPD psychopathology.

Game theory offers numerous models that can be used to characterize how interactions with other people can depart from what is rational and most advantageous (Webb, Reference Webb2006). This has the potential to illuminate clinical psychopathology (Montague et al. Reference Montague, Dolan, Friston and Dayan2012). Thus, BPD patients appear to lack the capacity to sustain mutually beneficial interactions with playing partners in an investment-trust game (King-Casas et al. Reference King-Casas, Sharp, Lomax-Bream, Lohrenz, Fonagy and Montague2008) associated with diminished insula activation in response to investment when compared to healthy controls. Here we tested, for the first time, the way that BPD patients and BD patients cooperated with social partners in an iterated (simultaneous) Prisoner's Dilemma (PD) game. PD games are the now classic mixed-motive formulation of the simple human dilemma in which two players must make choices to ‘cooperate’ or ‘defect’ for their sole or joint benefit. In their iterated form, PD games can provide an estimate of how individuals acquire and maintain patterns of reciprocal altruistic behaviour (Axelrod & Hamilton, Reference Axelrod and Hamilton1981). Cooperation can produce better outcomes for both parties but risks exploitation by partners; defection can maximize immediate benefits but at the risk of the breakdown of mutually beneficial exchanges. Such exchanges are arguably the common currency of human social behaviour: do I help you or do I help myself?

There were three important elements in the design of our study. First, we implemented PD games in which the participant's playing partner adopted a tit-for-tat strategy, repeating the last choice of the participant automatically. Extensive research shows that tit-for-tat is an effective strategy for eliciting cooperation from social partners (Axelrod & Dion, Reference Axelrod and Dion1988) and so for measuring when it is deficient in BPD or BD. Second, we included only female participants because BPD is thought to be more prevalent in women and there are significant gender differences in its co-morbidity (Tadic et al. Reference Tadic, Wagner, Hoch, Baskaya, von Cube, Skaletz, Lieb and Dahmen2009) and associated personality traits (Sansone & Sansone, Reference Sansone and Sansone2011) including novelty seeking (Sansone & Sansone, Reference Sansone and Sansone2011). Finally, to be sure that any sub-optimal behaviour in the PD game was not due to problems with basic processing of social stimuli, we included a choice reaction-time task to test the ability to use joint attention to speed categorization of visual targets; this latter task also provided an appropriate control for motivational deficits in our two clinical samples.

Method and materials

The study was approved by the Oxfordshire NHS research ethics committee. All participants gave written informed consent.

Samples

Participants were all female and aged between 18 and 60 years. There were 20 with diagnoses of DSM-IV BPD, 20 with DSM-IV BD (but without co-morbid BPD) and 20 healthy volunteers (HC) with no history of psychiatric illness. Patients were recruited from community settings: none had required hospital admission or crisis team support in the preceding month.

Clinical assessment and psychometric measures

Participants were screened by an experienced psychiatrist (K.S.) using the SCID-I and International Personality Disorders Examination (IPDE; Loranger et al. Reference Loranger, Sartorius and Janca1996) to confirm eligibility. All participants had a Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD) score of < 7 and a Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) score of < 7. Cognitive ability was estimated using Raven's Matrices (Raven et al. Reference Raven, Raven and Court2004), and trait aggression and impulsivity using the Buss–Perry Questionnaire (Buss & Perry, Reference Buss and Perry1992). Trait impulsivity was assessed with the Barratt Impulsivity Scale (BIS-11; Patton et al. Reference Patton, Stanford and Barratt1995).

The iterated PD game

Before playing the game, participants were introduced to a female ‘playing partner’ – in reality, a member of staff or student volunteer who acted as a confederate. It was explained that her computer was networked from another room in the building where she would be situated. In fact, the confederate's choices were entirely automated (see below).

We used an iterated (simultaneous) PD game previously reported by Rilling et al. (Reference Rilling, Gutman, Zeh, Pagnoni, Berns and Kilts2002). On each round of the PD games, participants were shown a visual display showing a 2 × 2 pay-off matrix (Fig. 1) which defined the four possible outcomes of each round (or trial) of the game: both players could cooperate (CC); participants could cooperate while their partners defected (CD), participants could defect while the partners cooperated (DC), or both players could defect (DD). The pay-offs for these outcomes conformed to the rule:

Fig. 1. Pay-off matrix for the four outcomes of an iterated, simultaneous Prisoner's Dilemma (PD) game played by 20 individuals with DSM-IV borderline personality disorder (BPD), 20 (euthymic) individuals with DSM-IV bipolar disorder (BD) and 20 non-clinical healthy controls. (All three groups were matched for age and cognitive ability.) Participants’ options are listed on top of columns and partners’ choices (in fact, a computer program playing tit-for-tat) are listed aside the rows. The pay-offs for each player, depending upon both players’ choices, are shown within each square; bold values = participants; values within parentheses = partners).

Participants were asked to cooperate or defect by pressing C or D on a standard keyboard. The participants made their choices without knowledge of their partners’ choice to cooperate or defect. If a PD game is played just once, the rational choice for any participant is to defect; this way s/he will do at least as well as her partner regardless of their own choices. However, in an iterated game, the rational strategy is to seek mutual cooperation that maximizes the gains of both players.

Participants played two PD games, each consisting of 20 rounds. The ‘partner’ started the first game by cooperating, and the second game, by defecting; thus, instantiating both cooperative and non-cooperative behaviour. Before starting, participants played four training rounds that demonstrated the four possible outcomes (CC, CD, DC, DD). At the end of the experimental session, participants were debriefed about the deception and specific consent was sought to use their data. All participants had believed they were playing with a real human partner.

Predictive gaze cueing

Twenty faces from the NimStim face database (Tottenham et al. Reference Tottenham, Tanaka, Leon, McCarry, Nurse, Hare, Marcus, Westerlund, Casey and Nelson2009) were arranged in pairs matched for gender, ethnicity and approximate age (Bayliss et al. Reference Bayliss, Griffiths and Tipper2009). All faces held a moderately positive (smiling) expression and were initially presented looking straight ahead. One of each pair was designated to Face group A or to Face group B. Each group comprised two pairs each of black males and black females, and three pairs of white males and white females. Previously, 12 independent raters had ensured that the pairs of faces were rated equally regarding attractiveness and trustworthiness, and that, as a whole, Face groups A and B were of roughly equal attractiveness and trustworthiness (Bayliss et al. Reference Bayliss, Griffiths and Tipper2009). The target to-be-categorized stimuli comprised pictures of 36 household objects, 18 of which were categorized as belonging in the kitchen and 18 in the garage.

At the start of each trial, participants fixated a central cross on the computer display. Following an interval of 600 ms, the cross was replaced by a face (see online Supplementary material). After another 1500 ms, the eyes of the face looked to the right or left. A household object appeared 500 ms later on the left or right of the display. Participants were instructed to decide, quickly and accurately, whether the object belonged in the garage (‘h’ key) or kitchen (spacebar key). If no response was made after 2500 ms, the trial was coded as an error, and the next trial presented. A blank screen was displayed for a 1500 ms inter-trial interval.

Participants completed two blocks of 120 trials, with 10 ‘valid’ faces that always looked towards the location of the subsequent target object and 10 ‘invalid’ faces that always looked in the opposite location (appearing 12 times in a random order, with randomly selected targets).

Statistics

PD

The proportion of cooperative responses was the primary outcome of interest. It was arcsine-transformed for statistical analysis (as is appropriate whenever variance is proportional to the mean; Howell, Reference Howell1987) and analysed with repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the between-subject factor of group and the within-subject factor of game (first or second). The proportion of cooperative choices following each of the four game outcomes (CC, DC, CD, DD) were analysed with repeated-measures ANOVAS with the between-subject factor of group and the within-subject factor of immediately previous outcome. All post-hoc tests were completed using one-sample t tests or Tukey's honestly significant difference test. Tables, figures and text report the original untransformed data.

A secondary analysis on mean deliberation times was completed, supplementary to the primary analysis.

Predictive gaze-cueing

Reaction times (ms) and error proportions were analysed using repeated-measure ANOVAs with the between-subject factor of group and the within-subject factor of cue validity. Trials with reaction times > 1500 ms were excluded.

Differences between the participant groups in age and psychometric scores were analysed by one-way ANOVA with the single factor of participant group.

Results

Sample characteristics

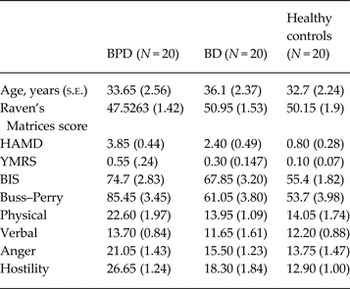

The BPD, BD and control participants were matched for age (F 2,57 = 0.524, p = 0.595) and cognitive ability as measured by Raven's Matrices (F 2,57 = 1.174, p = 0.316). Current symptoms of depression and mood elevation were low although the BPD group had significantly higher scores on the HAMD compared to the BD group and controls (F 2,57 = 13.5, p = 0.00) (Table 1). BPD participants reported lower trait and state positive affect (F = 4.391, p = 0.017; F = 4.539, p = 0.014) and higher trait and state negative affect (F = 26.9, p = 0.00; F = 12.16, p = 0.00) compared to the other two groups. BPD was also associated with significantly higher impulsivity (BIS-11, F = 13.275) and aggression (AQ, F 2,57 = 19.618) compared to BD and controls. Compared to controls, BD participants reported higher trait negative affect (t 38 = 3.099, p = 0.004) and reported higher levels of impulsivity (t 38 = 3.378, p = 0.002). While their total aggression scores did not differ from those of the controls, they reported significantly higher hostility (t 38 = 2.579, p = 0.014).

Table 1. Comparison of self-rating of demographics and self-reported trait and state affect and impulsivity in 20 individuals with DSM-IV borderline personality disorder (BPD), 20 (euthymic) individuals with DSM-IV bipolar disorder (BD) and 20 healthy controls

HAMD, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; YMRS, Young Mania Rating Scale; BIS, Barratt Impulsivity Scale.

BPD participants were significantly more likely to be taking antidepressant medication (χ2 1 = 3.600, p = 0.058) or receiving psychological treatment (χ2 1 = 6.144, p = 0.038) than the BD participants and the healthy controls (see online Supplementary material). However, there was no significant overall difference between the number of participants from each of the two clinical groups taking psychotropic medication (χ2 1 = 2.133, p = 0.144). Fourteen participants in the BPD group and nine in the BD group reported early physical or sexual abuse compared to none in the HC group. The was no significant difference between the two clinical groups (χ2 1 = 2.56, p = 0.11).

Iterated PD game

BPD participants made significantly fewer cooperative responses while playing the two iterated PD games compared with the BD and healthy control participants (see Fig. 2, F 2,57 = 4.243). Post-hoc Tukey tests showed that the BPD participants cooperated less frequently (0.5072 ± 0.0327) than both of the BD participants (0.6976 ± 0.05932) and controls (0.6791 ± 0.0564) (p < 0.05). By contrast, a post-hoc Tukey test revealed there was no difference in the proportion of cooperative responses in BD participants compared to controls (p = 0.964).

Fig. 2. Mean proportion of cooperative choices of 20 individuals with DSM-IV borderline personality disorder (BPD), 20 (euthymic) individuals with DSM-IV bipolar disorder (BD) and 20 non-clinical healthy controls in two iterated Prisoner's Dilemma games. In Game 1, playing partners opened with cooperative choices and then played (strict) tit-for-tat; in Game 2, playing partners opened with a defection and then (strict) played tit-for-tat. The dashed horizontal line indicates chance levels of cooperation rates (i.e. 0.5).

Both the BD participants and HC participants tended to make fewer cooperative responses on the second game compared to the first game (in response to their playing partners’ opening defection) (F 2,57 = 1.90, p = 0.175). However, this effect was absent for BPD participants whose cooperative responses did not markedly change between the first and the second game [see Fig. 2 (0.50 ± 0.050. v. 0.51 ± 0.036), F 1,19 = 0.13]. One-sample t tests against a baseline of 0.5 confirmed that both the BD participants and HCs tended to cooperate more frequently than they defected across the two games (t 19 = 3.331, p = 0.004; t 19 = 3.178, p = 0.005). By contrast, the proportions of cooperative responses in the BPDs were no greater than chance (t 19 = 0.219, p = 0.829).

Fig. 3 shows the proportion of cooperative responses following each of the four possible outcomes on the immediately preceding rounds of both games: CC (both players cooperated), CD (participants defected while partners cooperated), DC (participants cooperated while partners defected) and DD (both partners defected). BPD participants were significantly less likely than the BD participants and the HCs to cooperate following mutually cooperative outcomes (F 2,57 = 3.413, p = 0.040). In addition, the BPD participants tended to be less likely to cooperate following game outcomes in which they cooperated while their partners defected; however, this was not quite significant (F 2,57 = 2.415, p = 0.098).

Fig. 3. The proportion of cooperative choices following each of the four possible outcomes of the previous round of an iterated Prisoner's Dilemma games in 20 individuals with DSM-IV borderline personality disorder (BPD), 20 (euthymic) individuals with DSM-IV bipolar disorder (BD) and 20 non-clinical healthy controls; CC, both players cooperated (mutual cooperation); CD, participants cooperated while partners defected; DC, participants defected while partners cooperated; or both players could defect (mutual defection, DD).

All participants were faster to make their choices in the second PD game than the first game (F 1,57 = 37.86, p = 0.00) (see Table 2). Participants were also slighter (and non-significantly) faster to cooperate than defect (F 1,57 = 2.432, p = 0.125). There were no significant differences between the three groups in the times needed to decide to cooperate (F 2,57 = 0.521) or defect (F < 1). The BPD participants finished the PD games with smaller winnings compared to the BD participants and the controls (£12.52 v. £13.65 and £13.72, respectively) where, consistent cooperative behaviour would have yielded maximal winnings of £15.60. However, this reduction in winnings was not quite significant (F 2,57 = 2.33, p = 0.11).

Table 2. Mean deliberation times (ms) for decisions to cooperate or defect across two iterated Prisoner's Dilemma games in 20 individuals with DSM-IV borderline personality disorder (BPD), 20 (euthymic) individuals with DSM-IV bipolar disorder (BD) and 20 healthy controls

Finally, there were no significant associations between the proportions of cooperative responses on the one hand and trait scores of either impulsivity (BIS-11) or aggression (AQ) on the other hand, within either the BPD or the BD group (all r < 0.150). No significant differences in the proportion of cooperative responses was found to be associated with early abusive experiences in the two clinical groups (0.62 ± 0.061 v. 0.59 ± 0.046; F 1,38 = 0.172, p = 0.681). Age may be positively but weakly associated with increasing cooperation across all groups (combined, r = 0.128, p = 0.330) but does not explain the differences between cases and control groups.

Predictive gaze-cueing

Overall, mean reaction times when categorizing target objects as belonging in ‘garage’ v. ‘kitchen’ did not significantly differ between groups (F 2,57 = 0.623, p = 0.540) (see Fig. 4). Mean reaction times were significantly faster following presentation of valid compared to invalid faces (779.64 ± 13.02 v. 814 ± 13.59 ms, respectively). However, there was no evidence that this facilitation was markedly altered in the BPD participants (802.91 ± 24.6 v. 831.67 ± 24.15), BD participants (773.55 ± 23.63 v. 809.51 ± 27.98) and HCs (762.14 ± 19.339 v. 803.30 ± 18.76) (F 2,57 = 0.623, p = 0.540483).

Fig. 4. Mean correct reaction time (ms) for object categorizations following the presentation of spatially predictive gaze-cues (in ‘valid’ v. ‘invalid’ faces) in 20 females with diagnoses of DSM-IV borderline personality disorder, 20 females with DSM-IV bipolar-I disorder and 20 age- and cognitive ability-matched control participants.

Mean error rates were less than 6% and there were no differences in the proportion of errors that were observed between the three groups (0.054 ± 0.013 v. 0.040 ± 0.006 v. 0.044 ± 0.008) for BD, BPD and HCs, respectively (F 2,57 = 0.474, p = 0.627). Overall, participants made marginally fewer errors following the presentation of valid compared to invalid faces (4.42 ± 0.54% v. 5.00 ± 0.508%, F 1,57 = 1.873).

Discussion

Women with diagnoses of DSM-IV BPD showed patterns of reduced cooperation when compared to BD and healthy control women in two iterated PD games. In its iterated form, the PD presents a classical dilemma between self-interest and reciprocal cooperative behaviour in which social partners can make small sacrifices for their joint benefit but at the risk of exploitation, thus exhibiting reciprocal altruism (Axelrod & Dion, Reference Axelrod and Dion1988). In contrast to the other two groups, the BPD participants failed to cooperate more frequently than chance and failed to sustain cooperation following previous cooperative exchanges with their playing partners. Our groups were matched for age, cognitive ability and current symptoms with the BD and control groups, who did develop the expected pattern of mutual cooperation with their partners. Therefore, these findings provide support for our hypothesis that BPD is associated with difficulties in establishing and maintaining reciprocally cooperative relationships with a known and gender-matched social partner. By contrast, these deficits were absent in the BD patients who, if anything, tended to cooperate with their playing partners slightly more frequently than the HC participants.

These findings are unlikely to reflect non-specific cognitive difficulties in processing social signals. BPD participants shifted their visual attention on the basis of another person's direction of gaze just as effectively and quickly as the controls, and their deliberation times to cooperate or defect were not slowed in the PD games. These observations also argue against a general lack of engagement, a simple motivational deficit, or the effects of current medication.

Medication is difficult to avoid in representative clinical sample and both clinical groups were taking psychotropic medications, with an excess of SSRI treatment in the BPD group. Fluoxetine has been linked to pro-social behaviour in naturalistic (Raleigh et al. Reference Raleigh, McGuire, Brammer, Pollack and Yuwiler1991) and experimental settings (Knutson et al. Reference Knutson, Wolkowitz, Cole, Chan, Moore, Johnson, Terpstra, Turner and Reus1998), so higher prescription might have been expected to enhance cooperation in the BPD group (which did not occur). The same effect might be expected of psychological treatments, but only five of our BPD participants had attended group psychotherapy (and only two had completed the programme). Current mood symptoms could also have contributed to group differences but all participants had HAMD and YMRS scores of < 7 so are unlikely to be clinically significant. Tit-for-tat promotes cooperation in an iterated PD game for three reasons. First, it rewards cooperation but punishes defection. Second, cooperative responses (or defections) are rewarded (or punished) immediately in the following round of the game, helping players to link their own behaviour to the responses of their partners. Third, tit-for-tat is forgiving: players who have defected but then revert to cooperation are immediately rewarded with matching cooperative behaviour by their partners. Accordingly, the proportion of cooperative responses in our controls was above chance in the first and second PD games (0.708 ± 0.054, 0.635 ± 0.076), consistent with previous findings (Rilling et al. Reference Rilling, Gutman, Zeh, Pagnoni, Berns and Kilts2002; Wood et al. Reference Wood, Rilling, Sanfey, Bhagwagar and Rogers2006) while our BPD participants failed to show statistically significant cooperation in either game (0.503 ± 0.050, 0.510 ± 0.036).

Our data also help to clarify the character and extent of putative social deficits in euthymic BD. Previous reports suggested problems with emotion recognition, theory of mind and affective decision making (Adida et al. Reference Adida, Jollant, Clark, Besnier, Guillaume, Kaladjian, Mazzola-Pomietto, Jeanningros, Goodwin, Azorin and Courtet2011; Martino et al. Reference Martino, Strejilevich, Fassi, Marengo and Igoa2011) implying potential failure to anticipate the probable responses of playing partners or make cooperative choices. However, our euthymic BD patents were just as capable of developing cooperative relationships as healthy controls. This reflects clinical observations that stable BD patients frequently sustain high levels of social and occupational function.

There are several mechanisms that might contribute to the failure of our BPD participants to acquire and sustain cooperation. High trait aggression, hostility and impulsivity are clinically obvious features of BPD and impulsivity involves both decisional as well as motor processes (Lawrence et al. Reference Lawrence, Allen and Chanen2010; Svaldi et al. Reference Svaldi, Philipsen and Matthies2012); perhaps our BPD participants were unable to resist the temptation to maximize their immediate reward by defecting when their partners had cooperated? In fact, neither AQ hostility nor impulsivity scores were linked to the proportion of cooperative responses in any of the participant groups, and the BD participants also had elevated scores on the BIS-11 and the hostility sub-scale of the AQ, yet were indistinguishable from the controls. Moreover, if aggression or hostility played significant roles in the behaviour of the BPD participants, we might have expected levels of cooperation below chance rather than the (more or less) equal cooperation and defection observed.

A more persuasive explanation is that reduced cooperation simply reflects diminished reward value assigned to the experience of mutual cooperation by BPD participants. Mutually cooperative outcomes in the PD game used here elicit elevated blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) signals within the ventral striatum, perhaps representing reciprocal altruism (Rilling et al. Reference Rilling, Gutman, Zeh, Pagnoni, Berns and Kilts2002). Diminished reward value of mutual cooperation could be the corollary of failures to sustain relationships between individuals with BPD and their social partners. Further support for this possibility is provided by the diminished probability of further cooperative responses following mutually cooperative exchanges in the BPD participants compared to the BD patients and the healthy controls. Our findings suggest that the experience of joint cooperation may not be coded or experienced as rewarding for BPD participants as it is for BD and healthy controls, and consequently cannot then provide a basis for sustained future cooperation with even known social partners.

In the only other comparable experiment (using an investment game), BPD participants failed to increase the profits returned to less generous investors as a prompt to increase their next investment (King-Casas et al. Reference King-Casas, Sharp, Lomax-Bream, Lohrenz, Fonagy and Montague2008). This was interpreted as an unwillingness or inability to use ‘coaxing’ behaviours to repair or improve stressed or vulnerable relationships. This failure to use coaxing behaviour was associated with diminished BOLD amplitudes within the anterior cingulate cortex on receiving smaller than expected investments (King-Casas et al. Reference King-Casas, Sharp, Lomax-Bream, Lohrenz, Fonagy and Montague2008). Here, outcomes in which participants cooperated but their partners defected (DC) often elicited further cooperation as attempts to coax partners into cooperating again. This behaviour was absent in our BPD participants, in contrast to the ‘repairing’ behaviour shown by the BD and healthy controls, again possibility indicating the diminished reward value of future cooperation in BPD.

The potential causes of the cognitive failure we describe here are of interest. Early abusive experiences are often highlighted in BPD as possibly shaping psychopathology (Zanarini et al. Reference Zanarini, Gunderson, Marino, Schwartz and Frankenburg1989). However, between our clinical groups, there was no significant difference in the number of participants who reported early physical and/or sexual abuse. Moreover, the proportion of cooperative responses in those participants who reported early abuse was not significantly higher than in those who reported no abuse. Therefore reduced cooperation in BPD is not attributable simply to early abusive experiences. Indeed, BPD is much more heritable than usually believed (Torgersen et al. Reference Torgersen, Myers, Reichborn-Kjennerud, Roysamb, Kubarych and Kendler2012). Furthermore, the findings from twin studies of trust and ultimatum game performance (likely to be related to the PD performance) also suggest quite strong genetic underpinning (Wallace et al. Reference Wallace, Cesarini, Lichtenstein and Johannesson2007; Cesarini et al. Reference Cesarini, Dawes, Fowler, Johannesson, Lichtenstein and Wallace2008).

Accordingly, this kind of cognitive deficit has the potential to be a fundamental mechanism lending some specificity to BPD and explaining some key clinical phenomena. The question then becomes, when a patient is diagnosed with BPD, does it necessarily imply that the patient has BD? Our data show that by comparison with prototypical BD patients, BPD patients have an important neurocognitive deficit, not shown in BD. Further work is required on the mood instability that is so characteristic of BPD. This may also be explained by reduced social cognition as described here, but in the absence of convincing models of mood homoeostasis in man, the suggestion is hard to formalize. Overall, our findings do not support suggestions that BPD can yet be simply understood as allied with the bipolar spectrum (Akiskal et al. Reference Akiskal, Chen, Davis, Puzantian, Kashgarian and Bolinger1985; Atre-Vaidya & Hussain, Reference Atre-Vaidya and Hussain1999; Deltito et al. Reference Deltito, Martin, Riefkohl, Austria, Kissilenko and Corless2001). In conclusion, these results demonstrate for the first time that individuals with BPD, but not individuals with BD, fail to form reciprocally cooperative relationships with social partners in an iterated PD game. This behaviour may be mediated by or associated with a failure to derive reward value from mutual cooperation in social exchanges. We propose that that this deficit underlies defining social difficulties in BPD, increasing the likelihood of unpredictable behaviour with close friends and partners, and indeed with clinicians seeking to build therapeutic alliances. The operation of such a mechanism is open to further psychological (and neuroscientific) investigation and may permit improved understanding of aetiology. As importantly, it could provide an objective focus for measuring outcomes and developing more effective treatment.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0033291714002475.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Oxfordshire Health Services Research Committee. The funder did not have any role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data, preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Declaration of Interest

Professor Goodwin holds grants from Bailly Thomas, Medical Research Council, NIHR, Servier, holds shares in P1vital and has served as consultant, advisor or CME speaker for AstraZeneca, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cephalon/Teva Janssen-Cilag, Eli Lilly, Lundbeck, Otsuka, P1Vital, Roche, Servier, Shering Plough, Shire, Sunovion, Takeda. Dr Saunders and Professor Rogers report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interests.