Introduction

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a severe mental disorder characterized by pronounced difficulties in emotion regulation, interpersonal disturbances (e.g. frantic efforts to avoid abandonment), negative self-concept, and stress-related dissociation (APA, 2000; Skodol et al. Reference Skodol, Gunderson, Pfohl, Widiger, Livesley and Siever2002; Leichsenring et al. Reference Leichsenring, Leibing, Kruse, New and Leweke2011). During emotional and somatosensory challenge, individuals with BPD have shown alterations within a network of fronto-limbic brain regions that might underlie key features of this disorder (Leichsenring et al. Reference Leichsenring, Leibing, Kruse, New and Leweke2011; O‘Neill & Frodl, Reference O'Neill and Frodl2012).

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies of BPD consistently have shown amygdala hyperactivity during exposure to emotionally arousing pictures and fearful faces compared with healthy participants (Leichsenring et al. Reference Leichsenring, Leibing, Kruse, New and Leweke2011; O‘Neill & Frodl, Reference O'Neill and Frodl2012). Given the critical role of the amygdala in emotion processing (Davis & Whalen, Reference Davis and Whalen2001; Phillips et al. Reference Phillips, Drevets, Rauch and Lane2003; Phan et al. Reference Phan, Wager, Taylor and Liberzon2004; Ochsner & Gross, Reference Ochsner, Gross, Gross and Buck2007), hyperactivity of this area may underlie clinically well-observed BPD features such as emotional hypersensitivity and intense, long-lasting emotional reactions (Leichsenring et al. Reference Leichsenring, Leibing, Kruse, New and Leweke2011). Yet, contradictory results have also been reported (Ruocco et al. Reference Ruocco, Amirthavasagam, Choi-Kain and McMain2013), in accordance with findings from behavioural studies in BPD: whereas some studies revealed enhanced emotion detection, others showed emotion detection to be reduced in BPD (Lis & Bohus, Reference Lis and Bohus2013). Specific states may in fact modulate emotion processing and amygdala activation in BPD. For example, it has been proposed that limbic activation is dampened during states of dissociation (Sierra & Berrios, Reference Sierra and Berrios1998; Lanius et al. Reference Lanius, Vermetten, Loewenstein, Brand, Schmahl, Bremner and Spiegel2010b ), a core feature of BPD (APA, 2000). Moreover, some studies in BPD even found amygdala hyperactivity to normative neutral pictures (Donegan et al. Reference Donegan, Sanislow, Blumenberg, Fulbright, Lacadie, Skudlarski, Gore, Olson, McGlashan and Wexler2003; Koenigsberg et al. Reference Koenigsberg, Siever, Lee, Pizzarello, New, Goodman, Cheng, Flory and Prohovnik2009b ; Niedtfeld et al. Reference Niedtfeld, Schulze, Kirsch, Herpertz, Bohus and Schmahl2010; Schulze et al. Reference Schulze, Domes, Krüger, Berger, Fleischer, Prehn, Schmahl, Grossmann, Hauenstein and Herpertz2011; Krause-Utz et al. Reference Krause-Utz, Oei, Niedtfeld, Bohus, Spinhoven, Schmahl and Elzinga2012), possibly due to a tendency to interpret normative neutral stimuli as emotionally arousing, which may result in increased states of vigilance in BPD (Lis & Bohus, Reference Lis and Bohus2013).

Aside from limbic alterations, BPD patients have shown abnormal recruitment of frontal brain regions that are typically involved in top-down emotion regulation (Phillips et al. Reference Phillips, Drevets, Rauch and Lane2003; Banks et al. Reference Banks, Eddy, Angstadt, Nathan and Phan2007; Ochsner & Gross, Reference Ochsner, Gross, Gross and Buck2007; Etkin et al. Reference Etkin, Egner and Kalisch2011) and impulse control (Pessoa et al. Reference Pessoa, Padmala, Kenzer and Bauer2012). For example, BPD patients exhibited diminished recruitment of frontal brain regions including the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (dmPFC), dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) and orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), while being instructed to inhibit emotional processing (Koenigsberg et al. Reference Koenigsberg, Fan, Ochsner, Liu, Guise, Pizzarello, Dorantes, Guerreri, Tecuta, Goodman, New and Siever2009a ; Schulze et al. Reference Schulze, Domes, Krüger, Berger, Fleischer, Prehn, Schmahl, Grossmann, Hauenstein and Herpertz2011; Lang et al. Reference Lang, Kotchoubey, Frick, Spitzer, Grabe and Barnow2012) and during cognitive inhibition tasks (Silbersweig et al. Reference Silbersweig, Clarkin, Goldstein, Kernberg, Tuescher, Levy, Brendel, Pan, Beutel, Pavony, Epstein, Lenzenweger, Thomas, Posner and Stern2007). Moreover, BPD patients activated the ACC less than controls during exposure to fearful faces (Minzenberg et al. Reference Minzenberg, Fan, New, Tang and Siever2007) and trauma-related scripts (Schmahl et al. Reference Schmahl, Elzinga, Vermetten, Sanislow, McGlashan and Bremner2003, Reference Schmahl, Vermetten, Elzinga and Bremner2004).

Over the last decade, studying how brain regions interact in absence of goal-directed behaviour (resting-state functional connectivity; RSFC) has become increasingly important in understanding the neurobiology of psychiatric disorders (Greicius, Reference Greicius2008). Yet to date only two studies have investigated this in BPD (Wolf et al. Reference Wolf, Sambataro, Vasic, Schmid, Thomann, Bienentreu and Wolf2011; Doll et al. Reference Doll, Sorg, Manoliu, Wöller, Meng, Förstl, Zimmer, Wohlschläger and Riedl2013). Wolf and colleagues revealed altered connectivity within the default mode network, which has been related to pain processing and self-referential processes such as episodic memory and self-monitoring (Raichle et al. Reference Raichle, MacLeod, Snyder, Powers, Gusnard and Shulman2001; Greicius et al. Reference Greicius, Krasnow, Reiss and Menon2003). Compared with healthy participants, BPD patients showed increased RSFC in the left frontal pole and left insula as well as decreased RSFC in the left cuneus. BPD patients further exhibited decreased RSFC in the left inferior parietal lobule and right middle temporal cortex within a network comprising frontoparietal brain areas (task-positive network) compared with healthy individuals. Interestingly, RSFC of the insula and cuneus was positively correlated with self-reported dissociation (Wolf et al. Reference Wolf, Sambataro, Vasic, Schmid, Thomann, Bienentreu and Wolf2011).

Doll et al. (Reference Doll, Sorg, Manoliu, Wöller, Meng, Förstl, Zimmer, Wohlschläger and Riedl2013) reported altered RSFC in the default mode and task-positive networks, in line with the findings of Wolf et al. (Reference Wolf, Sambataro, Vasic, Schmid, Thomann, Bienentreu and Wolf2011). Moreover, BPD patients showed aberrant RSFC in the salience network, comprising the orbitofrontal insula and dorsal ACC (dACC). This network has been associated with interoceptive awareness, detection of salient events, encoding of unpleasant feelings, and a wide variety of cognitive tasks (Seeley et al. Reference Seeley, Menon, Schatzberg, Keller, Glover, Kenna, Reiss and Greicius2007; Menon & Uddin, Reference Menon and Uddin2010). Doll et al. (Reference Doll, Sorg, Manoliu, Wöller, Meng, Förstl, Zimmer, Wohlschläger and Riedl2013) further showed imbalanced connections between the three networks, most prominently a shift from RSFC in the task-positive to increased RSFC in the salience network in BPD patients. However, a drawback of both studies is that most patients were taking psychotropic medication.

Here, we investigate RSFC patterns in unmedicated individuals with BPD compared with age- and education-matched healthy controls (HC), using three seed regions of interest (ROIs) that are of particular relevance to BPD psychopathology based on current neurobiological models of the disorder and previous neuroimaging research (Leichsenring et al. Reference Leichsenring, Leibing, Kruse, New and Leweke2011). Each of these seed regions has been found to probe a specific intrinsic connectivity network: (1) bilateral amygdala (medial temporal lobe network); (2) dACC (salience network); and (3) ventral ACC (vACC) (default mode network). Based on previous research, we expected altered RSFC between our seeds and brain regions mainly located in the ventromedial (vm)/dmPFC, insula and occipital cortex in BPD patients. In addition, an exploratory analysis was carried out in the BPD group to assess the relationship between trait dissociation and RSFC of the three seeds.

Method

Participants

A total of 39 females aged between 18 and 45 years participated in this study. Two patients were excluded, because they reported to have fallen asleep during scanning. All participants underwent diagnostic assessments including the Structured Interview for DSM-IV Axis I (SCID-I; First et al. Reference First, Spitzer, Gibbon and Williams1997) and the International Personality Disorder Examination (IPDE; Loranger, Reference Loranger1999) by trained diagnosticians (inter-rater reliability: κ = 0.77 for all interviews). Clinical assessment included questionnaires on BPD symptom severity [Borderline Symptom List-95 (BSL-95); Bohus et al. Reference Bohus, Limberger, Frank, Chapman, Kuehler and Stieglitz2007], post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms and childhood trauma history [Post-traumatic Stress Diagnostic Scale (PDS), Foa, Reference Foa1995; Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ), Bernstein et al. Reference Bernstein, Stein, Newcomb, Walker, Pogge, Ahluvalia, Stokes, Handelsman, Medrano, Desmond and Zule2003], trait dissociation (Dissociation Experience Scale; DES; Bernstein & Putnam, Reference Bernstein and Putnam1986), dysphoric mood (Beck Depression Inventory; Beck et al. Reference Beck, Ward, Mendelson, Mock and Erbaugh1961), impulsivity (Barratt Impulsiveness Scale version 10; Patton et al. Reference Patton, Stanford and Barratt1995), difficulties in emotion regulation (Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale; Gratz & Roemer, Reference Gratz and Roemer2004), affect intensity (Affect Intensity Measure; Larsen, Reference Larsen1984) and current self-injurious behaviour.

General MRI exclusion criteria were: metal implants, pregnancy and left-handedness. BPD patients were free of medication within the last 14 days (in case of fluoxetine 28 days), free of severe somatic illness, and free of substance dependence within the last 6 months. Further exclusion criteria for the patient group were: current major depression, lifetime diagnoses of psychotic disorder, bipolar affective disorder, mental retardation, developmental disorder, and life-threatening suicidal crisis. Exclusion criteria for the HC group were: lifetime diagnoses of psychiatric and somatic disorders. The final patient group comprised 20 unmedicated females meeting criteria for BPD according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV; APA, 2000). All patients fulfilled DSM-IV criterion 6 for emotional instability and reported a history of physical, sexual and/or emotional trauma as assessed by the PDS and CTQ. Clinical characteristics and co-occurring mental conditions in the patient sample are reported in Table 1. In our BPD sample, nine patients met criteria for current co-morbid PTSD. The final HC group comprised 17 participants without a history of psychiatric disorders and trauma. The groups did not differ regarding age, education level and body mass index (see Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic and clinical variables in HC participants and patients with BPD

HC, Healthy control; BPD, borderline personality disorder; df, degrees of freedom; s.d., standard deviation; BMI, body mass index; BSL-95, Borderline Symptom List-95; CTQ, Childhood Trauma Questionnaire; DES, Dissociation Experience Scale; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

Procedure

The experiment was approved by the local medical ethics committee (University of Heidelberg, in accordance to the World Medical Association's Declaration of Helsinki) and conducted at the Central Institute of Mental Health in Mannheim, Germany. All participants were informed about the experiment and scanning procedure. Written informed consent was obtained. Before the scanning procedure, participants underwent diagnostic interviews (SCID-I and IPDE) and filled in the questionnaires on clinical characteristics. Acquisition of the resting-state scan was positioned first in the scan protocol. Participants were instructed to lie still with their eyes closed and not to fall asleep during this scan. Compliance with these instructions was verified as part of the exit interview. After the resting-state scan several anatomical and functional scans were acquired (Krause-Utz et al. Reference Krause-Utz, Oei, Niedtfeld, Bohus, Spinhoven, Schmahl and Elzinga2012). After scanning, participants were debriefed, thanked, and paid for their participation.

FMRI data acquisition

MRI scans were acquired on a Siemens TRIO-3 T MRI scanner using an eight-channel head coil (Siemens Medical Solutions, Germany). Whole-brain resting-state scans were acquired using T2*-weighted gradient-echo echo-planar imaging (EPI; 150 volumes, 40 sagittal slices scanned in ascending order, repetition time = 2500 ms, echo time = 30 ms, flip angle 80°, field of view = 220 × 220 mm, 3 mm isotropic voxels with no slice gap). A high-resolution three-dimensional T1-weighted anatomical image [MPRAGE (magnetization prepared rapid gradient echo), 1 mm isotropic voxels] was acquired for registration purposes. Head movement artifacts and scanning noise were restricted using head cushions and headphones within the scanner coil.

FMRI data preprocessing

Prior to analysis, all resting-state fMRI (RS-fMRI) datasets underwent a visual quality-control check to ensure that no gross artifacts were present in the data. Afterwards, data were analysed using FSL version 4.1.7 (FMRIB's Software Library; www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl) (Smith et al. Reference Smith, Jenkinson, Woolrich, Beckmann, Behrens, Johansen-Berg, Bannister, De Luca, Drobnjak, Flitney, Niazy, Saunders, Vickers, Zhang, De Stefano, Brady and Matthews2004). The following pre-processing steps were applied to EPI datasets: motion correction (Jenkinson et al. Reference Jenkinson, Bannister, Brady and Smith2002); removal of non-brain tissue (Smith et al. Reference Smith, Jenkinson, Woolrich, Beckmann, Behrens, Johansen-Berg, Bannister, De Luca, Drobnjak, Flitney, Niazy, Saunders, Vickers, Zhang, De Stefano, Brady and Matthews2004); spatial smoothing using a Gaussian kernel of 6 mm full width at half maximum; grand-mean intensity normalization of the entire four-dimensional dataset by a single multiplicative factor; a high-pass temporal filter of 100 s (i.e. ⩾0.01 Hz). The RS-fMRI dataset was registered to the T 1-weighted image, and the T 1-weighted image to the 2 mm isotropic Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) standard space image [T 1-weighted standard brain averaged over 152 subjects (MNI-152)] (Jenkinson & Smith, Reference Jenkinson and Smith2001; Jenkinson et al. Reference Jenkinson, Bannister, Brady and Smith2002). The resulting transformation matrices were combined to obtain a native to MNI space transformation matrix.

FMRI time course extraction and statistical analysis

A seed-based correlation analysis (Fox & Raichle, Reference Fox and Raichle2007) was employed to reveal brain areas that are functionally connected to a priori-defined seed ROIs during rest. The amygdala (medial temporal lobe network; MNI coordinates x = ± 23, y = − 4, z = − 19; Veer et al. Reference Veer, Oei, Spinhoven, van Buchem, Elzinga and Rombouts2011) was defined as the first seed region. The second seed region was the dACC (salience network; MNI coordinates x = ± 5, y = 19, z = 28, seed ‘I4’ in Margulies et al. Reference Margulies, Kelly, Uddin, Biswal, Castellanos and Milham2007). The third seed region was the vACC (default mode network; MNI coordinates x = ± 5, y = 47, z = 11, seed ‘S7’ in Margulies et al. Reference Margulies, Kelly, Uddin, Biswal, Castellanos and Milham2007). Spherical ROIs were created around these voxels using a radius of 4 mm. Next, all masks were registered to each participant's RS-fMRI pre-processed dataset using the inverse transformation matrix. The mean time courses were subsequently extracted from the voxels falling within each mask in native space. The time courses of the left and right seeds were entered as a regressor in a general linear model (GLM), for each of the three networks separately, together with nine nuisance regressors comprising the white matter signal, CSF signal, six motion parameters (three translations and three rotations) and the global signal. The latter regressor was included to further reduce the influence of artifacts caused by physiological signal sources (i.e. cardiac and respiratory) on the results (Fox & Raichle, Reference Fox and Raichle2007). However, because regression of the global signal can induce either anti-correlations or even group differences (Murphy et al. Reference Murphy, Birn, Handwerker, Jones and Bandettini2009; Saad et al. Reference Saad, Gotts, Murphy, Chen, Jo, Martin and Cox2012), we repeated all analysis without the global signal as a regressor in the model. Each individual model was tested using FEAT version 5.98, part of FSL, with contrasts for left and right seeds separately, as well as a contrast to assess functional connectivity of the left and right seeds together. The resulting individual parameter estimate maps, together with their corresponding within-subject variance maps, were then resliced into 2 mm isotropic MNI space and fed into a higher-level mixed-effects regression analysis and compared between groups (independent-samples t test). Post-hoc correlations were carried out between symptom severity scores (BSL-95) and brain regions showing significant between-group differences. In addition, an exploratory whole-brain analysis was conducted for the BPD group to investigate the relationship between trait dissociation scores (DES) and RSFC with each of the three seeds. To this end, a higher-level mixed-effects regression analysis was carried out including DES scores as the regressor of interest, for each of the three networks separately. All statistical images were whole-brain corrected for multiple comparisons using cluster-based thresholding with an initial cluster-forming threshold of Z > 2.3 and a corrected cluster significance threshold of p < 0.017 (p < 0.05, Bonferroni corrected for the three networks tested; Worsley, Reference Worsley, Jezzard, Matthews and Smith2001). Based on our a priori hypothesis on altered amygdala–medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) connectivity, a small volume correction was applied for mPFC regions, including the perigenual ACC, vm/dmPFC and OFC. A combined mask of these ROIs was created based on the Harvard–Oxford cortical probability atlas, as provided in FSL, which was then used to mask the raw statistical images. Subsequently, correction for multiple comparisons was carried out for those voxels present in the mask (mPFC) using cluster-based thresholding with the same parameter settings as for the whole-brain analysis (Z > 2.3, p < 0.017).

Since nine BPD patients additionally met criteria for PTSD, we ran an additional post-hoc analysis to assess the effects of co-morbidity on functional connectivity (details from this analysis can be found in the online Supplementary material).

Results

Amygdala connectivity (medial temporal lobe network)

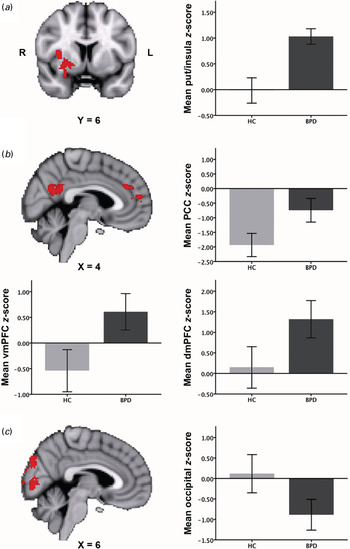

Overall, amygdala RSFC in both groups was highly similar to the patterns previously described in the literature (Roy et al. Reference Roy, Shehzad, Margulies, Kelly, Uddin, Gotimer, Biswal, Castellanos and Milham2009; Veer et al. Reference Veer, Oei, Spinhoven, van Buchem, Elzinga and Rombouts2011) (online Supplementary Fig. S1a). At our stringent threshold of p < 0.017, no differences were observed between the two groups. However, a trend was observed for a cluster comprising the lateral OFC, putamen and dorsal insula (p < 0.05, whole brain corrected; Fig. 1 a): While HC showed no RSFC between the right amygdala and this cluster, this positive functional connection was present in BPD patients (see Table 2). Our ROI analysis of amygdala–mPFC RSFC did not yield any differences between the two groups.

Fig. 1. Between-group differences (Z>2.3, p < 0.017; whole brain cluster corrected, except for Fig. 1 a: Z >2.3, p < 0.05) in functional connectivity of each of the three seeds: (a) amygdala (medial temporal lobe network); (b) dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) (salience network); (c) ventral ACC (default mode network). Connectivity differences are overlaid on the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) 2 mm standard space template. Bar graphs plot the mean Z scores (± 2 standard errors of the mean) in each group for each of the regions where connectivity differences were found. R, Right; L, left; put, putamen; HC, healthy controls; BPD, borderline personality disorder patients; PCC, posterior cingulate cortex; vmPFC, ventromedial prefrontal cortex; dmPFC, dorsomedial prefrontal cortex.

Table 2. Resting-state functional connectivity results: between-groups effects

MNI, Montreal Neurological Institute; BPD, borderline personality disorder patients; HC, healthy control subjects; ACC, anterior cingulate cortex.

a All Z values are cluster corrected for multiple comparisons (p < 0.017, corrected), except for Z values with an asterisk (*) (p < 0.05, corrected).

dACC connectivity (salience network)

In both patients and controls the pattern of brain regions comprising the salience network (see online Supplementary Fig. S1b) overlapped with connectivity patterns found in previous studies (Seeley et al. Reference Seeley, Menon, Schatzberg, Keller, Glover, Kenna, Reiss and Greicius2007; Menon & Uddin, Reference Menon and Uddin2010). Fig. 1 b illustrates regions in which group differences in bilateral dACC RSFC were observed between BPD patients and HC (also see Table 2). While HC showed strong negative RSFC between bilateral dACC and left posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), decreased negative RSFC between these regions was found in BPD patients. Additionally, increased dACC RSFC with two clusters in the dmPFC/paracingulate cortex was found in BPD patients compared with HC. In BPD patients, both clusters were positively correlated with the dACC. In HC, the lower cluster showed negative connectivity and the upper cluster showed diminished connectivity with the dACC (see Table 2).

vACC connectivity (default mode network)

Both BPD patients and HC demonstrated vACC connectivity with well-described areas of the default mode network including the PCC, precuneus and lateral parietal cortex (Raichle et al. Reference Raichle, MacLeod, Snyder, Powers, Gusnard and Shulman2001; Greicius et al. Reference Greicius, Krasnow, Reiss and Menon2003) (see online Supplementary Fig. S1c). BPD patients showed increased negative RSFC between left vACC and area V1 of the occipital cortex, lingual gyrus and cuneus compared with HC, who exhibited marginal RSFC with these regions (see Fig. 1 c and Table 2).

In the patient group, there were no significant correlations between BPD symptom severity scores (BSL-95) and the functional connectivity strength of any of the brain regions in which between-group differences were found.

Exploratory analysis: trait dissociation and functional connectivity

In the patient group, correlations were found between self-reported DES scores and amygdala RSFC with several brain regions. First, a positive correlation with left amygdala–right dlPFC RSFC was observed (Fig. 2 a and Table 3), illustrating stronger RSFC between these regions in BPD patients with higher self-reported trait dissociation. Second, DES scores differentially modulated left amygdala RSFC with a cluster in the occipital lobe including the lingual gyrus, intracalcarine cortex and fusiform gyrus (see Fig. 2 b and Table 3), demonstrating increasing negative RSFC between these regions with higher DES scores. Correlations for bilateral amygdala RSFC were similar to those found for the left amygdala. No associations were found with RSFC of the two other seeds.

Fig. 2. Voxelwise correlations (Z>2.3, p < 0.017; whole brain cluster corrected) between trait dissociation scores (measured using the Dissociation Experience Scale; DES) and amygdala functional connectivity in the borderline group: (a) positive association of left amygdala–dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) connectivity with trait dissociation; (b) negative association of left amygdala–occipital cortex connectivity (including the lingual gyrus, intracalcarine cortex and fusiform gyrus) with trait dissociation. Results are overlaid on the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) 2 mm standard space template. Scatter plots illustrate the direction of the correlation, with mean Z scores plotted against the dissociation scores.

Table 3. Resting-state functional connectivity results: DES associations with amygdala connectivity in the BPD patient group

DES, Dissociation Experience Scale; BPD, borderline personality disorder; MNI, Montreal Neurological Institute.

a All Z values are cluster corrected for multiple comparisons (p < 0.017).

Effects of global signal regression (GSR)

Reanalysis without the global signal revealed highly similar results. Although some of the effects did not survive the stringent multiple comparison correction, these could still be observed at a more lenient threshold (see online Supplementary Figs S2 and S3 and online Supplementary Tables S1 and S2).

Subgroup analysis

No differences were found between BPD with or without co-morbid PTSD. Full results of this analysis are reported in the online Supplementary material (Fig. S4).

Discussion

Here we investigated RSFC in unmedicated BPD patients compared with HC. Three seeds of high relevance to BPD psychopathology were chosen, each probing a specific brain network: (1) bilateral amygdala (medial temporal lobe network); (2) dACC (salience network); and (3) vACC (default mode network). In both groups, we replicated connectivity patterns reported in previous studies (Margulies et al. Reference Margulies, Kelly, Uddin, Biswal, Castellanos and Milham2007; Veer et al. Reference Veer, Oei, Spinhoven, van Buchem, Elzinga and Rombouts2011).

Overall, RSFC differences between BPD patients and controls were observed within networks associated with the processing of negative emotions, encoding of salient events, and self-referential processing. The results per seed are discussed in more detail below.

Amygdala connectivity (medial temporal lobe network)

The amygdala plays a key role in emotion processing and the initiation of fear and stress responses (Davis & Whalen, Reference Davis and Whalen2001; Phillips et al. Reference Phillips, Drevets, Rauch and Lane2003; Phan et al. Reference Phan, Wager, Taylor and Liberzon2004; Ochsner & Gross, Reference Ochsner, Gross, Gross and Buck2007), and has functional connections with the perigenual ACC, insula and OFC (Stein et al. Reference Stein, Wiedholz, Bassett, Weinberger, Zink, Mattay and Meyer-Lindenberg2007). The insula and OFC have been implicated in identifying the emotional significance of internal and external stimuli and the generation of emotional responses (Phillips et al. Reference Phillips, Drevets, Rauch and Lane2003; Kringelbach & Rolls, Reference Kringelbach and Rolls2004; Banks et al. Reference Banks, Eddy, Angstadt, Nathan and Phan2007; Ochsner & Gross, Reference Ochsner, Gross, Gross and Buck2007; Etkin et al. Reference Etkin, Egner and Kalisch2011). Several studies in BPD patients have reported hyperactivity of the amygdala and insula during emotional challenge (Niedtfeld et al. Reference Niedtfeld, Schulze, Kirsch, Herpertz, Bohus and Schmahl2010; Schulze et al. Reference Schulze, Domes, Krüger, Berger, Fleischer, Prehn, Schmahl, Grossmann, Hauenstein and Herpertz2011; Leichsenring et al. Reference Leichsenring, Leibing, Kruse, New and Leweke2011; Krause-Utz et al. Reference Krause-Utz, Oei, Niedtfeld, Bohus, Spinhoven, Schmahl and Elzinga2012; O‘Neill & Frodl, Reference O'Neill and Frodl2012). In the present study, we found a stronger coupling between the amygdala and a cluster comprising the dorsal insula, OFC and putamen in BPD patients than in HC, even in the absence of experimental conditions. Since this effect did not pass the more stringent correction for testing multiple seeds, our interpretation has to be taken with caution. Nevertheless, in the context of earlier studies, our trend finding of amygdala hyperconnectivity with other brain regions highly relevant to emotion processing could reflect the clinically well-observed BPD feature of affective hyperarousal and intense emotional reactions. Indeed, high levels of aversive affective arousal, often accompanied by dissociative experiences, are a major characteristic of BPD (Linehan, Reference Linehan1993; Stiglmayr et al. Reference Stiglmayr, Shapiro, Stieglitz, Limberger and Bohus2001, Reference Stiglmayr, Ebner-Priemer, Bretz, Behm, Mohse, Lammers, Anghelescu, Schmahl, Schlotz, Kleindienst and Bohus2008). Affective hyperarousal often leads to self-inflicted harm, suicidal acts and dysfunctional impulsive behaviour patterns, therefore having detrimental consequences in patients with BPD (Chapman et al. Reference Chapman, Gratz and Brown2006; Kleindienst et al. Reference Kleindienst, Bohus, Ludaescher, Limberger, Kuenkele, Ebner-Priemer, Chapman, Reicherzer, Stieglitz and Schmahl2008).

In addition, we observed a stronger coupling between the amygdala and putamen in BPD patients than in controls. Being part of the basal ganglia, the putamen is involved in movement control (Packard & Knowlton, Reference Packard and Knowlton2002) and may play an important role in mobilizing an individual to take action in the face of contempt and disgust (Zeki & Romaya, Reference Zeki and Romaya2008). Furthermore, both the OFC and the putamen play an important role in reward processing, reinforcement learning and impulsivity (Packard & Knowlton, Reference Packard and Knowlton2002; Kringelbach & Rolls, Reference Kringelbach and Rolls2004; Haber & Knutson, Reference Haber and Knutson2010), which is another key feature of BPD.

ACC connectivity (salience network, default mode network)

Being an important constituent of the salience network, the dACC has been related to the detection of salient events and a wide variety of cognitively demanding tasks (Critchley et al. Reference Critchley, Mathias and Dolan2001; Dosenbach et al. Reference Dosenbach, Visscher, Palmer, Miezin, Wenger, Kang, Burgund, Grimes, Schlaggar and Petersen2006; Sridharan et al. Reference Sridharan, Levitin and Menon2008; Menon & Uddin, Reference Menon and Uddin2010). Moreover, recent studies have highlighted the role of the dACC and orbitofrontal insula in switching between different large-scale networks and reallocating cognitive resources in the face of salient events. Across different samples of healthy participants, Sridharan et al. (Reference Sridharan, Levitin and Menon2008) have demonstrated that activation in the dACC temporally precedes activity in nodes of other networks such as the PCC. In other studies, healthy individuals recurrently showed strong anti-correlations between ‘task-positive’ brain regions (e.g. dACC) and brain regions commonly activated during rest (e.g. PCC) (Fox et al. Reference Fox, Snyder, Vincent, Corbetta, van Essen and Raichle2005; Buckner & Vincent, Reference Buckner and Vincent2007; Neumann et al. Reference Neumann, Fox, Turner and Lohmann2010).

Notably, in the present study, HC showed a negative association between the dACC and PCC compared with BPD patients, who exhibited diminished anti-correlations between these regions. Moreover, BPD patients showed a stronger RSFC of our seed with the dmPFC, whereas healthy participants showed diminished connectivity between these regions. The dmPFC has been critically implicated in self-referential processes such as processing of autobiographical memories and monitoring of internal cognitive and affective states (Buckner & Vincent, Reference Buckner and Vincent2007).

Our findings of diminished interaction between core regions of the salience and default mode networks could suggest impaired flexibility in switching between the networks. Similarly, a recent RS-fMRI study in BPD patients reported imbalanced inter-network connectivity between the default mode network and the salience network (Doll et al. Reference Doll, Sorg, Manoliu, Wöller, Meng, Förstl, Zimmer, Wohlschläger and Riedl2013). Although the nature of these interactions between brain networks is not yet fully understood, our findings might relate to an increased vigilance even to seemingly neutral events in individuals with BPD (Kluetsch et al. Reference Kluetsch, Schmahl, Niedtfeld, Densmore, Calhoun, Daniels, Kraus, Ludaescher, Bohus and Lanius2012; Lis & Bohus, Reference Lis and Bohus2013).

BPD patients further showed decreased RSFC between the left vACC and area V1 of the occipital cortex, lingual gyrus and cuneus compared with controls, who showed only marginal RSFC between these regions. In part, these findings are in line with previous fMRI studies in BPD, which reported altered RSFC within the default mode network in BPD (Wolf et al. Reference Wolf, Sambataro, Vasic, Schmid, Thomann, Bienentreu and Wolf2011; Doll et al. Reference Doll, Sorg, Manoliu, Wöller, Meng, Förstl, Zimmer, Wohlschläger and Riedl2013). More specific, Wolf et al. (Reference Wolf, Sambataro, Vasic, Schmid, Thomann, Bienentreu and Wolf2011) observed altered RSFC in the left cuneus as well as in the insula and frontopolar cortex in BPD patients compared with HC. Diminished RSFC in occipital areas within the default mode network may be associated with an inflexible integration of sensory stimuli into self-referential processing in individuals with BPD (Wolf et al. Reference Wolf, Sambataro, Vasic, Schmid, Thomann, Bienentreu and Wolf2011).

Trait dissociation and functional connectivity

Our exploratory analysis revealed negative correlations between self-reported trait dissociation and amygdala RSFC with the cuneus, area V1 of the occipital lobe and the fusiform gyrus in BPD patients, partly in line with findings by Wolf et al. (Reference Wolf, Sambataro, Vasic, Schmid, Thomann, Bienentreu and Wolf2011). Diminished amygdala RSFC in occipital areas may represent an altered gating of sensory input associated with self-reported dissociation (Lanius et al. Reference Lanius, Williamson, Bluhm, Densmore, Boksman, Neufeld, Gati and Menon2005). Wolf et al. (Reference Wolf, Sambataro, Vasic, Schmid, Thomann, Bienentreu and Wolf2011) further found positive correlations between self-reported dissociative states and insula RSFC, which were not observed in the present study. Instead, we revealed positive correlations between self-reported dissociation and left amygdala RSFC in the right dlPFC – a brain area involved in working memory, attention deployment and inhibitory control of emotions (Ochsner & Gross, Reference Ochsner, Gross, Gross and Buck2007). It has been proposed that dissociation is associated with increased prefrontal inhibition of limbic brain activation, which reflects an overmodulation of emotional arousal (Lanius et al. Reference Lanius, Vermetten, Loewenstein, Brand, Schmahl, Bremner and Spiegel2010b ). Indeed, states of dissociation negatively predicted amygdala activation during emotional interference in BPD patients with a history of trauma (Krause-Utz et al. Reference Krause-Utz, Oei, Niedtfeld, Bohus, Spinhoven, Schmahl and Elzinga2012). Further neuroimaging studies are needed to gain more insight into the neurobiological underpinnings of this complex phenomenon.

Several limitations need to be addressed: First, since all of our patients reported a history of interpersonal trauma – which is highly prevalent in BPD (APA, 2000; Leichsenring et al. Reference Leichsenring, Leibing, Kruse, New and Leweke2011) – our findings could also be related to the history of interpersonal trauma in general, rather than to BPD psychopathology in particular. However, although a recent study in participants with a history of childhood maltreatment demonstrated abnormal amygdala RSFC with the putamen and insula (van der Werff et al. Reference van der Werff, Pannekoek, Veer, van Tol, Aleman, Veltman, Zitman, Rombouts, Elzinga and van der Wee2013), this connection was decreased rather than increased. Further, the presence of co-morbid conditions limits the specificity of our results as well, even though most individuals with BPD have additional Axis I disorders (Leichsenring et al. Reference Leichsenring, Leibing, Kruse, New and Leweke2011). More specific, nine patients in the present BPD sample additionally met criteria for PTSD. As aberrant amygdala (Rabinak et al. Reference Rabinak, Angstadt, Welsh, Kenndy, Lyubkin, Martis and Phan2011; Sripada et al. Reference Sripada, King, Garfinkel, Wang, Sripada, Welsh and Liberzon2012) and default mode (Daniels et al. Reference Daniels, McFarlane, Bluhm, Moores, Clark, Shaw, Williamson, Densmore and Lanius2010; Lanius et al. Reference Lanius, Bluhm, Coupland, Hegadoren, Rowe, Théberge, Neufeld, Williamson and Brimson2010a ) RSFC has been observed in PTSD patients previously, a post-hoc comparison between BPD patients with or without co-morbid PTSD was carried out. This revealed no significant differences between subgroups, while BPD patients with and without co-morbid PTSD all differed significantly from HC in each cluster found in the main analysis but one. In addition, DES scores predicted amygdala connectivity with the dlPFC and occipital cortex to the same extent in both BPD subgroups. These results suggest that group differences found in our study cannot be explained merely by the presence of co-morbid PTSD. Nevertheless, future studies have to compare BPD patients with patients with other disorders (for example, PTSD) to clarify whether the alterations in RSFC described here are truly specific to BPD.

Second, although seed-based connectivity analyses are well suited to address hypothesis-driven questions, results are inherently limited to the connections of the seeds that are chosen a priori. This means that differences between BPD patients and controls in neural circuits not associated with one of our seeds might have gone unobserved in the current study. Data-driven methods (including independent component analysis), as used by Wolf et al. (Reference Wolf, Sambataro, Vasic, Schmid, Thomann, Bienentreu and Wolf2011) in BPD, do have the potential to look at the data in a more exploratory fashion.

Third, blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) measurements of the amygdala are susceptible to physiological confounds due to its proximity to draining veins. To remove variance associated with these confounding signal sources, we used GSR. Although this method has been proven to be useful in dealing with physiological artifacts and generally increases connection specificity, it is also known to introduce anti-correlations in connectivity analyses (Murphy et al. Reference Murphy, Birn, Handwerker, Jones and Bandettini2009). Recent research on simulated data demonstrated that GSR could promote connectivity differences between groups due to differences in the underlying noise structure, even when these do not exist (Saad et al. Reference Saad, Gotts, Murphy, Chen, Jo, Martin and Cox2012). Therefore, we repeated all analyses without GSR and observed highly similar results, though some effects were only found subthreshold. Nevertheless, although the relative difference in connectivity between the groups persisted, the sign of some connections changed depending on adding the global signal or not. Consequently, the connections described here for each group should not be taken as absolute measures of coherence, but rather as relative with respect to the other regressors in the regression model. Importantly, reduced connectivity in the occipital cortex was also observed in a previous RS-fMRI study of the default mode network in BPD patients that used a different analysis method without GSR (Wolf et al. Reference Wolf, Sambataro, Vasic, Schmid, Thomann, Bienentreu and Wolf2011).

Last, BPD patients included in our study had been free of psychotropic medication at least 2 weeks prior to the study to exclude acute effects of medication on our results. Nevertheless, it cannot be ruled out that psychotropic medication might have had long-term effects on brain network organization in our patient group.

In summary, we observed differences between BPD patients and HC in RSFC of brain regions of high relevance to the disorder. More specific, our findings suggest connectivity changes in brain networks associated with the processing of negative emotions, encoding of salient events and self-referential processing in individuals with BPD compared with healthy individuals. Importantly, our findings corroborate previous resting-state connectivity studies in BPD, suggesting an impaired flexibility to switch between large-scale networks during rest. RS-fMRI has the potential to map network differences in BPD, and may thereby shed more light on the role of abnormal brain functional connectivity in this disorder.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0033291714000324.

Acknowledgements

A.K.-U. was funded by a Ph.D. stipend from the German Research Foundation (SFB636). B.M.E. and S.A.R.B.R. were funded by VIDI grants from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) and by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research – National Initiative Brain and Cognition (NWO-NIHC, project no. 056-25-010). We thank all participants of this study, as well as Claudia Stief and Birgül Sarun for their collaboration in this study.

Declaration of Interest

None.