Alcohol consumption is recognized as a major public health problem (World Health Organization, 2014), high alcohol consumption being an important risk factor for chronic diseases, disability, and early mortality (Rehm et al. Reference Rehm, Mathers, Popova, Thavorncharoensap, Teerawattananon and Patra2009; Roerecke & Rehm, Reference Roerecke and Rehm2013). Alcohol use disorders are fairly common mental disorders; for example, it has been estimated that the 12-month prevalence of alcohol use disorder is around 14% in the United States (Grant et al. Reference Grant, Goldstein, Saha, Chou, Jung and Zhang2015). Psychological consequences of alcohol use have also been demonstrated in studies where long-term alcohol use has been associated with aggressive behavior in close relationships (Bushman & Cooper, Reference Bushman and Cooper1990), impaired emotional processing (Maurage et al. Reference Maurage, Grynberg, Noël, Joassin, Hanak and Verbanck2011; Kornreich et al. Reference Kornreich, Brevers, Canivet, Ermer, Naranjo and Constant2013), and poor mental health (Boden & Fergusson, Reference Boden and Fergusson2011). However, it remains unclear whether alcohol use has broader psychological implications in terms of personality trait change. In the current study, we examined whether three different measures of alcohol use are associated with changes in the five major personality traits.

Personality traits and alcohol consumption

The five major personality traits (i.e. Big Five; extraversion, emotional stability, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness) describe individual differences in stable patterns of feelings, thoughts, and behaviors. Although absolute stability of personality traits between individuals is relatively high (Roberts & DelVecchio, Reference Roberts and DelVecchio2000), personality traits are subject to change. Important normative changes in personality traits have been well established, i.e. levels of emotional stability, agreeableness, and conscientiousness have been found to increase with age (Roberts et al. Reference Roberts, Walton and Viechtbauer2006).

From the numerous studies that have examined the association between the five major personality traits and alcohol use, cross-sectional meta-analyses have shown higher alcohol consumption among individuals with high neuroticism, low agreeableness, and low conscientiousness (Bogg & Roberts, Reference Bogg and Roberts2004; Malouff et al. Reference Malouff, Thorsteinsson, Rooke and Schutte2007). Similarly, individuals with alcohol-related substance disorder appear to have higher levels of neuroticism and lower levels of conscientiousness when compared with control participants in cross-sectional meta-analysis (Kotov et al. Reference Kotov, Gamez, Schmidt and Watson2010). Individual longitudinal studies have provided similar evidence; higher extraversion, higher neuroticism, and lower agreeableness have been associated with future alcohol problems in the Midlife in the United States (MIDUS) study (Turiano et al. Reference Turiano, Whiteman, Hampson, Roberts and Mroczek2012), and high neuroticism has been associated with increased problematic alcohol use among young adults in a twin study (Hicks et al. Reference Hicks, Durbin, Blonigen, Iacono and McGue2012).

In our previous individual-participant meta-analysis of over 70 000 participants from eight cohort studies where the association between personality and alcohol consumption was examined, higher extraversion and lower conscientiousness were associated with increased risk of transitioning from moderate to heavy alcohol consumption over time, whereas higher neuroticism and lower agreeableness were associated with heavy alcohol consumption only cross-sectionally (Hakulinen et al. Reference Hakulinen, Elovainio, Batty, Virtanen, Kivimäki and Jokela2015a). Alcohol abstinence was associated with lower extraversion, higher neuroticism, higher agreeableness, and lower openness. Except for neuroticism, these associations were replicated in longitudinal analysis of transitioning from moderate consumption to abstinence (Hakulinen et al. Reference Hakulinen, Elovainio, Batty, Virtanen, Kivimäki and Jokela2015a).

Contrary to the numerous studies examining the association between personality traits with alcohol use, limited number of studies have examined alcohol use as a contributor to personality trait change over the life course. Moreover, most of these studies have concentrated on neuroticism or more specific personality constructs such as impulsivity. High alcohol consumption has been associated with increasing novelty seeking, sensation seeking, and impulsivity in college samples (Quinn et al. Reference Quinn, Stappenbeck and Fromme2011; Littlefield et al. Reference Littlefield, Vergés, Wood and Sher2012). In the Minnesota Twin Family Study, young adults who had an alcohol use disorder over two time points had lower normative decline in neuroticism (Hicks et al. Reference Hicks, Durbin, Blonigen, Iacono and McGue2012). Similarly, decrease in alcohol-related problems was found to co-vary with decrease in neuroticism and increase in conscientiousness in small sample college students who were followed over 16 years (Littlefield et al. Reference Littlefield, Sher and Wood2009, Reference Littlefield, Sher and Wood2010). In a sample of 2245 college students, quitting binge drinking was associated with a normative decline in neuroticism (Ashenhurst et al. Reference Ashenhurst, Harden, Corbin and Fromme2015). In a recent study by Allen et al. (Reference Allen, Vella and Laborde2015) using a nationally representative sample of over 10 000 Australian adults, alcohol consumption was not associated with mean level personality trait change. However, increase in alcohol consumption was associated with increase in neuroticism (Allen et al. Reference Allen, Vella and Laborde2015), indicating that changes in alcohol consumption could lead to changes in personality traits. Taken together, there is evidence that alcohol use at least in early adulthood is associated with changes in personality traits. However, the evidence is scarce and there is a lack of large-scale studies on the topic. Moreover, it is also not known whether changes shown by previous studies can be found after adolescence and young adulthood when personality traits are more stable (Roberts et al. Reference Roberts, Walton and Viechtbauer2006).

The present study

The present study examines whether alcohol use is associated with changes in Big Five personality traits using data from six longitudinal cohort studies with over 39 000 participants. We pooled these studies for an individual-participant meta-analysis, which provided us high statistical power and allowed us to examine how similar the results were across individual studies. We used three common measures of alcohol use: average alcohol consumption based on the units of alcohol consumed, frequency of binge drinking, and alcohol-related problems. In addition to these measures, we also examined whether a global indicator of risky alcohol use was associated with personality trait change. This enabled us to identify those individuals who had a risky alcohol use in any of the three measures we used. We examined first study-specific associations, which were then pooled using individual-participant meta-analysis.

Methods

Following the approach of previous personality-health individual-participant meta-analytic studies (Jokela et al. Reference Jokela, Batty, Nyberg, Virtanen, Nabi and Singh-Manoux2013a, Reference Jokela, Hintsanen, Hakulinen, Batty, Nabi and Singh-Manouxb), we searched two international data archives, ICPSR (http://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/ICPSR) and UK Data Service (http://ukdataservice.ac.uk/), to identify potential large-scale cohort studies that contain repeated measures of alcohol consumption and personality traits. We used the following criteria for inclusion: (A) studies needed to be open access, (B) had information on participant's alcohol consumption, alcohol-related problems or binge drinking, (C) had a fairly large sample size (n > 1000), and (D) personality traits measured twice with the brief 15-item or more comprehensive personality trait questionnaire based on the Five-Factor Model of personality. The following six cohort studies met these criteria: the German Socio-Economic Panel Study (GSOEP); the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey; the Health and Retirement Study (HRS); the MIDUS; the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study graduate (WLSG) sample, and the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study sibling (WLSS) sample. These studies and measures are described in detail in online Supplementary appendix.

In short, GSOEP began in 1984 and it is a longitudinal survey of private households (Wagner et al. Reference Wagner, Frick and Schupp2007). The original sample included 5921 households and 12 245 individual respondents. HILDA is a household-based panel study which began in 2001 including a large national probability sample of Australian households occupying private dwellings (n = 7682 households with 19 914 individuals at baseline) (Wooden & Watson, Reference Wooden and Watson2007). HRS is a nationally representative longitudinal study that began in 1992 and it includes more than 30 000 individuals representing the US population older than 50 years (Juster & Suzman, Reference Juster and Suzman1995). MIDUS is based on a nationally representative random-digit-dial sample of 7108 English-speaking adults who were between 25 and 74 years old in 1995–1996 (Brim et al. Reference Brim, Baltes, Bumpass, Cleary, Featherman and Hazzard2011). The WLSG consists of 10 317 randomly selected participants who were born between 1937 and 1940 and who graduated from Wisconsin high schools in 1957 (Herd et al. Reference Herd, Carr and Roan2014). In addition to the main graduate sample, data has been collected on a selected sibling of a sample of the graduates (WLSS). Although the data collection in adulthood has been very similar between graduate and sibling samples, in the current study, graduate and sibling samples were treated separately as the sibling sample is more heterogeneous in terms of age.

Measures

The following standardized questionnaire instruments were used to assess five major personality traits (extraversion, neuroticism, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness to experience): 15-item version of the Big Five Inventory (BFI) was used in GSOEP (John et al. Reference John, Donahue and Kentle1991, Reference John, Naumann, Soto, John, Robins and Pervin2008); 36-item inventory based on the Saucier's and Goldberg's Big Five Markers Scale was used in HILDA (Saucier, Reference Saucier1994); 25-item questionnaire was used in HRS and MIDUS (Lachman and Weaver, Reference Lachman and Weaver1997); and 29-item version of the BFI was used in WLSG and WLSS (John et al. Reference John, Donahue and Kentle1991, Reference John, Naumann, Soto, John, Robins and Pervin2008). Although some of these instruments are rather short, different instruments measuring the Big Five personality traits have considerable convergent validity (John et al. Reference John, Naumann, Soto, John, Robins and Pervin2008), indicating good reliability across personality traits measures.

Three different measures of alcohol use were slightly differently available across included cohort studies. Heavy alcohol consumption was measured in units of consumed alcohol and defined as follows: men – more than 14 units per week; women – more than seven units per week. However, there were two exceptions, in GSOEP participants were asked how often they drank beer, wine, spirits, and mixed drinks, which were self-reported using a four-point scale (0 = never, 1 = seldom, 2 = once in a while, 3 = regularly) and heavy alcohol consumption was defined as a score of 7 or more on the summed score of these four questions. In the MIDUS baseline, participants reported how many times during the past 12 months they had used much larger amounts of alcohol than they intended to or had used them for a longer period of time than they intended to. Participants who answered 3–5 times or more during the past 12 months were defined as heavy alcohol consumers. In MIDUS follow-up, WLSG, and WLSS, a participant was defined as binge drinker if he/she consumed more than five units of alcohol on the same occasion during last month, whereas in HRS, a cut-off of more than four units during last 3 months was used. Data on binge drinking were not available in HILDA, MIDUS baseline, and GSOEP. Alcohol-related problems were defined according to the criteria of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) (Babor et al. Reference Babor, Higgins-Biddle, Saunders and Monteiro2001). Participant was defined as having alcohol problem if he/she had at least one AUDIT symptom (e.g. felt bad or guilty about drinking, felt need to cut down drinking, drinking caused problems at work). Data on alcohol-related problems were not available from HILDA and GSOEP. To identify those individuals who had a risky alcohol consumption in any of the three measures, we also created a global indicator of risky alcohol consumption, which was defined as the absence v. presence of any of the three indicators.

Other measures included sex, age, and race/ethnicity (0 = white, non-Hispanic; 1 = other), and these measured were acquired from self-reported questionnaires and face-to-face interviews.

Statistical analysis

Change in personality traits was examined by predicting personality trait score at T2 by alcohol use at T1, adjusting for personality trait score at T1, age, sex, race/ethnicity, and the length of follow-up time in months between T1 and T2. Heavy alcohol consumption, binge drinking, alcohol problems, and risky alcohol use were used as predictors in separate models. In addition, to examine robustness of the findings, risky alcohol use at T2 was also used as a predictor in a separate model. For easier interpretation of effect sizes, personality traits were first transformed into T-scores (mean = 50, standard deviation = 10) by using means and standard deviations at T1 as the reference to which personality scores at both T1 and T2 were standardized.

To compare and quantify the obtained effect sizes in more detail, we examined how large the personality trait change associated with alcohol use was in relation to the average change in personality traits over time. The average changes in the personality traits were estimated by pooling the study-specific personality trait change scores in separate meta-analyses. For this analysis, linear personality trait change was assumed, and only participants 50 years or older were included to avoid non-linear changes in personality traits, which have been shown to occur at younger ages and on longer follow-up periods (Roberts et al. Reference Roberts, Walton and Viechtbauer2006). Differences in follow-up times between studies were taken into account by assuming a linear association between the years of follow-up and degree of personality trait change. Thus, before carrying out the meta-analysis, in each study we divided the raw change scores by follow-up time (in years) and multiplied this by 5 to give an estimate of average personality trait change per 5 years of age. This allowed us to compare normative personality trait change with effect sizes in the associations between alcohol use and personality trait change.

Analyses were first performed in each study separately and then the obtained estimates were pooled together. Due to small number of included studies, instead of using random-effects meta-analysis, fixed-effect meta-analysis was used. Heterogeneity in the effect sizes was examined using the I 2 estimates. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata, version 13.1, and metan command package was used for conducting meta-analyses.

Results

Descriptive characteristics of the study participants are shown in Table 1. In total, current study included 39 772 (54% women) participants with a mean age of 51.5 years and a mean follow-up time of 5.6 years. The percentage of individuals classified as heavy alcohol consumers at the baseline (T1) ranged from 8% in HRS to 21% in GSOEP.

Table 1. Descriptive characteristics of the study participants in the included cohort studies

Due to missing data in covariate variables, numbers of covariate frequencies may not add up to the total number of participants with personality and baseline alcohol consumption data. GSOEP, German Socio-Economic Panel Study; HILDA, Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia; HRS, Health and Retirement Study; MIDUS, Midlife in the United States; WLSG, Wisconsin Longitudinal Study Graduate Sample; WLSS, Wisconsin Longitudinal Study Sibling Sample; T1, baseline; T2, follow-up, s.d., standard deviation.

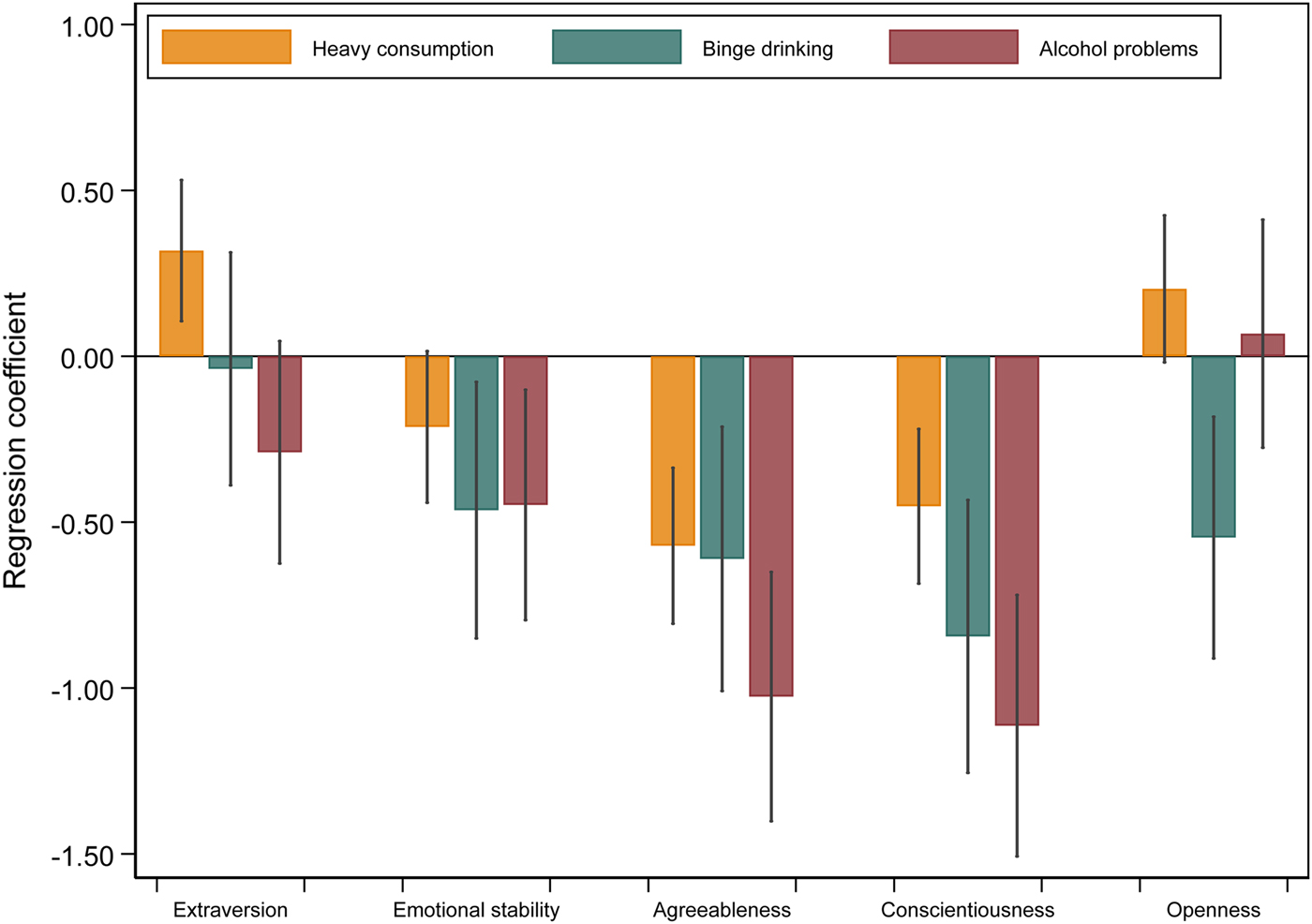

Associations between baseline heavy alcohol consumption, alcohol problems and binge drinking with personality trait changes are presented in Fig. 1 (for cohort-specific associations, please see online Supplementary Figs 1–3). Except for no association between heavy alcohol consumption and emotional stability, heavy alcohol consumption, having alcohol problems and binge drinking were associated with decreasing emotional stability, agreeableness and conscientiousness. There was significant heterogeneity across studies in the association between heavy alcohol consumption and decreasing conscientiousness (I 2 = 76%, p = 0.001), but not in the other associations. Heavy alcohol consumption was also associated with increasing extraversion, and binge drinking was associated with decreasing openness. However, there was considerable heterogeneity in both associations [heavy alcohol consumption and extraversion (I 2 = 77%, p = 0.001); binge drinking and openness (I 2 = 78%, p = 0.01)].

Fig. 1. The associations between heavy alcohol consumption, binge drinking, and alcohol problems with the change in personality traits.

Associations between baseline risky alcohol use and risky alcohol use at follow-up with personality trait change are shown in Fig. 2 (cohort-specific associations are presented in online Supplementary Figs 4–5). Baseline risky alcohol use was associated with increasing extraversion [0.25 T-scores; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.07–0.44] and with decreasing emotional stability (−0.28; 95% CI −0.48 to −0.08), agreeableness (−0.67; 95% CI −0.87 to −0.36), and conscientiousness (−0.58; 95% CI −0.79 to −0.38). Similarly, risky alcohol use at the follow-up was associated with increasing extraversion (0.43; 95% CI 0.15–0.71) and with decreasing emotional stability (−0.61; 95% CI −0.90 to −0.31), agreeableness (−0.40; 95% CI −0.71 to −0.09), and conscientiousness (−0.67; 95% CI −0.98 to −0.36).

Fig. 2. The associations between any risky alcohol use at the baseline and at the follow-up with the change in personality traits.

Change from risky alcohol use to non-risky alcohol use over the follow-up was associated with decreasing extraversion (−0.36; 95% CI −0.69 to −0.02) and with increasing agreeableness (0.51; 95% CI 0.14–0.88) and conscientiousness (0.38; 95% CI 0.01–0.75) (cohort-specific associations are presented in online Supplementary Fig. 6). No association between change from risky to non-risky alcohol use with changes in emotional stability was found. No substantial heterogeneity in the estimates were found.

Analyses examining average personality trait change among participants aged 50 years or older showed that extraversion decreased (−0.42 per 5-year increase in age; 95% CI −50 to −0.34), emotional stability increased (0.91; 95% CI 0.83–1.00), agreeableness remained stable (−0.04; 95% CI −0.13 to 0.06), conscientiousness decreased (−0.52; 95% CI −0.62 to −0.42), and openness to experience decreased (−0.64; 95% CI −0.72 to −0.56) over the follow-up (cohort-specific results are shown in online Supplementary Fig. 7). Thus, risky alcohol use at baseline reversed the average age-related personality trait change by 3 years in extraversion [=(0.25/−0.42) × 5 = −3] and 1.5 years in emotional stability. In addition, risky alcohol use at baseline accelerated the age-related decline in conscientiousness by 5.6 years. Around similar effect sizes were observed between risky alcohol use at follow-up and average personality trait change.

Discussion

The present pooled analysis of six prospective cohort studies examined whether alcohol use is associated with personality trait change assessed over several years of follow-up. Results showed that alcohol use was associated with increasing extraversion and decreasing emotional stability, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. Except the association between alcohol use and extraversion, these results were robust across studies from different countries and across different measures of alcohol use. These findings suggest that alcohol use is associated with personality trait change.

Our findings are in line with the previous studies where high alcohol consumption have been associated with decrease in emotional stability (Littlefield et al. Reference Littlefield, Sher and Wood2009, Reference Littlefield, Sher and Wood2010; Hicks et al. Reference Hicks, Durbin, Blonigen, Iacono and McGue2012; Ashenhurst et al. Reference Ashenhurst, Harden, Corbin and Fromme2015). Many of the previous studies on the topic have been conducted on college students (Littlefield et al. Reference Littlefield, Sher and Wood2009, Reference Littlefield, Sher and Wood2010, Reference Littlefield, Vergés, Wood and Sher2012; Quinn et al. Reference Quinn, Stappenbeck and Fromme2011), which might explain some differences in findings between current and previous studies. However, current results are in line with studies where low emotional stability, low agreeableness and low conscientiousness have been associated with current and future high alcohol consumption (Bogg & Roberts, Reference Bogg and Roberts2004; Malouff et al. Reference Malouff, Thorsteinsson, Rooke and Schutte2007; Hakulinen et al. Reference Hakulinen, Elovainio, Batty, Virtanen, Kivimäki and Jokela2015a). In addition, current findings highlight the possibility that alcohol use and personality traits could form a vicious cycle where personality traits lead to increase in alcohol use that in turn contributes to harmful personality change. Recently, this kind of co-development from early adolescence to early adulthood has been demonstrated in a study using the Minnesota Twin Family Study data (Durbin & Hicks, Reference Durbin and Hicks2014).

In terms of effect sizes, heavy alcohol consumption and binge drinking had a rather modest effect on personality trait change (around 0.5 T-score units that correspond to 0.05 standard deviations), whereas the effect size for alcohol problems was slightly higher for alcohol-related problems in the change of agreeableness and conscientiousness (around 1 T-score units that correspond to 0.1 standard deviations). However, these effect sizes were similar when compared with the average change of personality traits per 5 years. Moreover, the effect sizes were higher than the effect of an increase of depressive symptoms on neuroticism (Hakulinen et al. Reference Hakulinen, Elovainio, Pulkki-Råback, Virtanen, Kivimäki and Jokela2015b), but similar than the effect of onset of a single chronic disease on personality traits (Jokela et al. Reference Jokela, Hakulinen, Singh-Manoux and Kivimäki2014b). Thus, the effect of alcohol use on personality trait change seems to be comparable with the previously reported predictors of personality trait change. When compared with the average age-related personality change, risky alcohol use attenuated the normative personality change by 3 years in extraversion and 1.5 years in emotional stability. Moreover, risky alcohol use accelerated the normative age-related decline in conscientiousness by 5.6 years. This highlights how risky alcohol use can accelerate or decelerate normative personality trait change after middle age to one way or another.

Potential mechanisms

A number of biological, psychological, and social mechanisms could explain the present findings. Long-term alcohol use has been associated with impaired emotional recognition and decoding (Maurage et al. Reference Maurage, Grynberg, Noël, Joassin, Hanak and Verbanck2011; Kornreich et al. Reference Kornreich, Brevers, Canivet, Ermer, Naranjo and Constant2013), which could explain how alcohol consumption contributes to a decrease in emotional stability. Alcohol use also increases the release of dopamine that leads to changes in the extended amygdala, which in turn can increase reactivity to stress and decrease in emotional stability (Volkow et al. Reference Volkow, Koob and McLellan2016). Last, it is well known that heavy alcohol consumption impairs mental health (Boden & Fergusson, Reference Boden and Fergusson2011). Personality trait emotional stability and mental health problems have a strong association (Kotov et al. Reference Kotov, Gamez, Schmidt and Watson2010; Hakulinen et al. Reference Hakulinen, Elovainio, Pulkki-Råback, Virtanen, Kivimäki and Jokela2015b), which could explain why high alcohol consumption predicts a decrease in emotional stability.

Association between alcohol use with a number of aggressive reactions and conflicts in relationships is well established (Bushman & Cooper, Reference Bushman and Cooper1990; Foran & O'Leary, Reference Foran and O'Leary2008). These findings could in part explain why risky alcohol use was associated with decreasing agreeableness in the current study. It is, for example, possible that risky alcohol use leads to problems in social relationship, which in turn result in decrease in the number of social relationships. Moreover, alcohol use can impair executive functions (e.g. impair executive behavioral control and disinhibit impulsive responding) leading to poor control of cognitive behavior (Heinz et al. Reference Heinz, Beck, Meyer-Lindenberg, Sterzer and Heinz2011), which in turn can increase aggressive behavior.

Alcohol use has been associated with poorer decision-making and with impairments, especially in the goal-directed decision-making (Sebold et al. Reference Sebold, Deserno, Nebe, Schad, Garbusow and Hägele2014). In addition, as alcohol begins to impair executive control, explicit cognitive processes start to diminish and implicit impulsive processes dominate (Wiers & Stacy, Reference Wiers and Stacy2006). These effects could also be seen as lowering conscientiousness. Low socioeconomic positioning over the life course could also explain the increased alcohol consumption and low conscientiousness in adulthood (Collins, Reference Collins2016; Sutin et al. Reference Sutin, Luchetti, Stephan, Robins and Terracciano2017). From the Five Factor personality traits, low conscientiousness has been most systematically associated with poor health outcomes, such as obesity (Jokela et al. Reference Jokela, Hintsanen, Hakulinen, Batty, Nabi and Singh-Manoux2013b) and onset of diabetes (Jokela et al. Reference Jokela, Elovainio, Nyberg, Tabák, Hintsa and Batty2014a), and poor health behaviors (Bogg & Roberts, Reference Bogg and Roberts2004; Hakulinen et al. Reference Hakulinen, Elovainio, Batty, Virtanen, Kivimäki and Jokela2015a, Reference Hakulinen, Hintsanen, Munafò, Virtanen, Kivimäki and Battyc; Wilson & Dishman, Reference Wilson and Dishman2015; Sutin et al. Reference Sutin, Stephan, Luchetti, Artese, Oshio and Terracciano2016). Moreover, low conscientiousness has also been associated with higher risk of early mortality (Jokela et al. Reference Jokela, Batty, Nyberg, Virtanen, Nabi and Singh-Manoux2013a). Thus, long-term alcohol use could potentially lead to lower conscientiousness that in turn could contribute to the development of chronic diseases.

Regarding extraversion, in the current study, only heavy alcohol consumption – but not binge drinking or alcohol-related problems – was associated with increasing extraversion. This finding may be related to a difference between heavy alcohol consumption associated with social drinking but not with problem-related drinking. In addition, drinking has been found to lift up mood among highly extraverted individuals (Fairbairn et al. Reference Fairbairn, Sayette, Wright, Levine, Cohn and Creswell2015), which could partly explain the current finding.

The association between alcohol use and personality change could also be partially mediated by the characteristics of the social environment. In certain environments, alcohol use is more common and factors such as peer pressure and social norms have been associated with heavy alcohol use (Borsari & Carey, Reference Borsari and Carey2001). Thus, these factors could also act as mechanisms from alcohol use to personality trait change.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of the current study include prospective data from six cohort studies and three different measures of alcohol use. The present study has also some limitations. Participants were mainly white and middle-aged adults, and thus results might not be generalizable to younger participants or to other ethnic groups. Alcohol use was self-reported, which has been associated with under-reporting of alcohol use (Stockwell et al. Reference Stockwell, Zhao and Macdonald2014). It is also not known whether personality traits influence the accuracy and truthfulness of alcohol use self-reports. Moreover, alcohol use was measured slightly differently across studies, which could lead to the misclassification of alcohol use and introduce heterogeneity in the associations. Although personality traits were measured with different instruments, it has been shown that the Big Five personality trait measures have considerable convergent validity (John et al. Reference John, Naumann, Soto, John, Robins and Pervin2008), suggesting that different measures of personality traits are unlikely a source of major heterogeneity.

There are also a number of factors that could confound current results. Negative life events such as job loss have been associated with alcohol consumption and personality trait change (Boyce et al. Reference Boyce, Wood, Daly and Sedikides2015; de Goeij et al. Reference de Goeij, Suhrcke, Toffolutti, van de Mheen, Schoenmakers and Kunst2015), and thus they could potentially lead to both increase in alcohol consumption and personality trait change. However, naturally it is also possible that alcohol use before negative life event causes problems at work and in personal relationships, which in turn lead to personality trait change. Our finding that a change from risky alcohol use to non-risky alcohol use over the follow-up was associated with increasing agreeableness and conscientiousness, suggests that associations between alcohol risky use and personality trait change are also reversible.

Conclusion

The present study using data from six prospective cohort studies suggests that alcohol use is associated with increasing extraversion and decreasing emotional stability, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. These findings suggest that alcohol use is associated with personality trait change after middle age.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291718000636

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the original collectors of the data and ICPSR (Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research; www.icpsr.umich.edu) for making the data available for research use. Neither the original collectors of the data nor the Archive bear any responsibility for the analyses or interpretations presented here. The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors. Part of the preliminary results of the current study have been presented in the 16th European Conference of Personality (19.−23.7.2016), Timisoara, Romania. Data from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey are used in the current study. The HILDA Project was initiated and is funded by the Australian Government Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA) and is managed by the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research (Melbourne Institute). The findings and views reported in this paper, however, are those of the author and should not be attributed to either FaHCSIA or the Melbourne Institute. The HRS (Health and Retirement Study) is sponsored by the National Institute on Aging (grant number NIA U01AG009740) and is conducted by the University of Michigan. Since 1995 the MIDUS study has been funded by the following: John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Research Network, National Institute on Aging (P01-AG020166), and National institute on Aging (U19-AG051426). This research uses data from the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study (WLS) of the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Since 1991, the WLS has been supported principally by the National Institute on Aging (AG-9775, AG-21079, AG-033285, and AG-041868), with additional support from the Vilas Estate Trust, the National Science Foundation, the Spencer Foundation, and the Graduate School of the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Since 1992, data have been collected by the University of Wisconsin Survey Center. A public use file of data from the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study is available from the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1180 Observatory Drive, Madison, Wisconsin 53706 and at http://www.ssc.wisc.edu/wlsresearch/data/.

Declaration of interest

None.