Introduction

Depression and dementia are frequent clinical disorders in the elderly (Korczyn & Halperin, Reference Korczyn and Halperin2009). Several studies have found depression or depressive symptoms to be associated with subsequent dementia (e.g. Dotson et al. Reference Dotson, Beydoun and Zonderman2010; Saczynski et al. Reference Saczynski, Beiser, Seshadri, Auerbach, Wolf and Au2010; Köhler et al. Reference Köhler, Van Boxtel, Jolles and Verhey2011; Li et al. Reference Li, Wang, Shofer, Thompson, Peskind, McCormick, Bowen, Crane and Larson2011; Wilson et al. Reference Wilson, Barnes, Mendes de Leon, Aggarwal, Schneider, Bach, Pilat, Beckett, Arnold, Evans and Bennett2002). Possible biological mechanisms linking depression and subsequent dementia are: interactions with vascular diseases, changes in glucocorticoid steroid levels that can result in hippocampal atrophy, accumulation of amyloid-β plaques, inflammatory processes, and lack of nerve growth factors (Byers & Yaffe, Reference Byers and Yaffe2011).

Ownby et al. (Reference Ownby, Crocco, Acevedo, John and Loewenstein2006) suggested that depression might be a risk factor for rather than a prodrome of subsequent Alzheimer's disease (AD) because they found a positive association between the risk for AD and the interval of depression and AD diagnoses. Indeed, both hypotheses concerning the association between depression and later dementia might not exclude each other (Jorm, Reference Jorm2000, Reference Jorm2001). In a recent review, Byers & Yaffe (Reference Byers and Yaffe2011) stated that although most studies found an association between late-life depression and dementia, whether it constitutes a risk factor or a prodromal feature is questionable.

Therefore, the current state of knowledge regarding depression as a prodromal feature of dementia can be described as inconclusive. Besides the above-mentioned problems, one reason for this may be diverging definitions of depression in general and of late-onset depression in particular. Most studies used either screening scales for depressive symptoms or clinical diagnoses of depression. Those few studies that used different parameters (i.e. history of depression and depressive symptoms) of depression were underpowered (Geerlings et al. Reference Geerlings, den Heijer, Koudstaal, Hofman and Breteler2008), used only abbreviated (Li et al. Reference Li, Wang, Shofer, Thompson, Peskind, McCormick, Bowen, Crane and Larson2011), or no (Gatz et al. Reference Gatz, Tyas, St. John and Montgomery2005) inquiries to assess clinical diagnoses of depression, or examined only two follow-ups every 2 years (Lenoir et al. Reference Lenoir, Dufouil, Auriacombe, Lacombe, Dartigues, Ritchie and Tzourio2011).

To overcome these gaps in the literature, we assessed current depressive symptoms with a well-established depression scale for elderly populations, and a history of clinical diagnosis of major depression according to DSM-IV criteria in a large sample over three follow-up periods every 1½ years.

In addition to the previously mentioned problems, there is no consistent definition of late-onset depression. Several studies used an age of 60 years as the cut-off for late-onset depression (e.g. Van Reekum et al. Reference Van Reekum, Simard, Clarke, Binns and Conn1999; Geerlings et al. Reference Geerlings, den Heijer, Koudstaal, Hofman and Breteler2008), but there are also studies that used 45 years (Steffens et al. Reference Steffens, Plassman, Helms, Welsh-Bohmer, Saunders and Breitner1997) or 50 years (Zalsman et al. Reference Zalsman, Aizenberg, Sigler, Nashony, Karp and Weizman2000; Li et al. Reference Li, Wang, Shofer, Thompson, Peskind, McCormick, Bowen, Crane and Larson2011). Different cut-offs for late-onset depression might explain divergent results concerning subsequent dementia.

To determine the temporal association between depression and subsequent dementia, we analysed different cut-offs for depression onset in detail. A prodrome as an early sign of a pathological process is characterized by temporal adjacency of the symptom and later manifestation of the disease. It is a mild or qualitatively different early expression of a pathological process. If depression is a prodromal state of dementia, there should be a closer temporal proximity between onset of depression and dementia and no remission of depressive symptoms indicated by a late- or very late-onset of depression and currently elevated depressive symptoms. A risk factor is a circumstance that increases the probability to subsequently develop the disease. It has an indirect and mediated effect on the pathological process. If depression is a risk factor for subsequent dementia, history of depression in general, early-onset depression with or without current depressive symptoms or late-onset depression without current depressive symptoms should be associated with subsequent dementia. We believe that the combination of late- or very late-onset depression with currently elevated depressive symptoms represents a neurodegenerative process (i.e. a prodromal state of dementia), whereas an association between a late- or very late-onset depression that remitted and currently shows no elevation of depressive symptoms and subsequent dementia represents an indirect effect (i.e. a risk factor for subsequent dementia).

Depression is frequent in subjects with mild cognitive impairment (Panza et al. Reference Panza, Frisardi, Capurso, D`Introno, Colacicco, Imbimbo, Santamato, Vendemiale, Seripa, Pilotto, Capurso and Solfrizzi2010). It remains unclear whether depression might predict incident dementia independently of cognitive impairment. Perception of subjective memory impairment might occur even before objective cognitive impairment and might be part of affective disorders or symptoms (Reisberg et al. Reference Reisberg, Prichep, Mosconi, John, Glodzik-Sobanska, Boksay, Monteiro, Torossian, Vedvyas, Ashraf, Jamil and de Leon2008). More complaints about subjective memory impairment have been found in depressed persons (O'Connor et al. Reference O'Connor, Pollitt, Roth, Brook and Reiss1990; Riedel-Heller et al. Reference Riedel-Heller, Matschinger, Schork and Angermeyer1999; Jorm et al. Reference Jorm, Butterworth, Anstey, Christensen, Easteal, Maller, Mather, Turakulov, Wen and Sachdev2004); therefore, we included subjective memory impairment as well as objective cognition. All-cause dementia in general and AD and dementia of other aetiology in particular were used as target variables.

Method

Sample

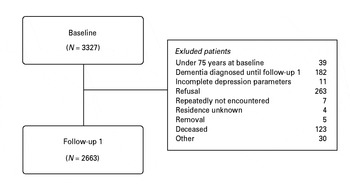

We present data from a prospective and population-based multi-centre study [the German Study on Ageing, Cognition, and Dementia in Primary Care Patients (AgeCoDe)]. At baseline, participants aged ⩾75 years were recruited via general practitioners (GPs) in six German cities (Bonn, Düsseldorf, Hamburg, Leipzig, Mannheim, Munich). Inclusion criteria were absence of dementia according to the judgement of the GP and at least one contact with the GP within the past 12 months. Exclusion criteria were consultations only by home visits, severe illness, insufficient knowledge of the German language, deafness or blindness, and lack of capability for informed consent. The relevant ethics committees approved the study. The interview was conducted in-person by a trained research assistant (psychologist or physician). Follow-up assessments after baseline in 2003/2004 were conducted every 1½ years. History of major depression was first assessed in follow-up 1. Consequently, the present study referred to data of covariates and predictors (i.e. depression parameters and cognitive measures) in follow-up 1 and included information of dementia status until follow-up 4. Follow-up 4 was conducted approximately 4½ years after follow-up 1. The sample initially consisted of 3327 baseline participants. We excluded participants aged <75 years at baseline (n = 39) and participants with a diagnosis of dementia at baseline or follow-up 1 (n = 182). Of 2674 participants personally interviewed in follow-up 1, both depression parameters were available for 2663 subjects who constitute the sample of the present study (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Sample selection flowchart.

Assessment of depression

A shortened and modified version of section E of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI; Wittchen & Pfister, Reference Wittchen and Pfister1997) was used to assess lifetime prevalence and age of onset of major depression according to DSM-IV criteria (APA, 1994) at follow-up 1. Major depression was diagnosed when the symptom algorithm according to CIDI was met (i.e. at least one core symptom, at least three or four accessory symptoms depending on the number of core symptoms for at least 2 weeks, and bereavement exclusion). Core symptoms were ‘depressed mood’ and ‘loss of interest or pleasure in nearly all activities’ and accessory symptoms were ‘fatigue’, ‘loss or increase of appetite/weight’, ‘changes in sleeping patterns’, ‘psychomotor agitation/inhibition’, ‘feelings of worthlessness or guilt’, ‘difficulty concentrating’, and ‘suicidal thoughts or intentions’. We did not ask for accessory symptoms (‘loss of sexual interest’, ‘indecisiveness’), mixed episodes, clinical significance/impairment criterion, substance abuse or medical contribution (e.g. hyperthyreosis).

The short version of the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15; Yesavage et al. Reference Yesavage, Brink, Rose, Lum, Huang, Adey and Leirer1983; Sheikh & Yesavage, Reference Sheikh, Yesavage and Brink1986) in German was used to assess depressive symptoms at follow-up 1. GDS-15 consists of 15 items in terms of questions referring to the last week that can be accepted or rejected. If more than two items were missing, the GDS-15 score could not be computed. If one or two items were missing, a weighted score was computed. Clinically relevant depression is supposed to be indicated by a score of at least 6 (e.g. Wancata et al. Reference Wancata, Alexandrowicz, Marquart, Weiss and Friedrich2006). To provide better comparability with the clinical diagnosis of depression, a GDS-15 score dichotomized by a cut-off score of 6 was entered into our prediction models. When we report no current depressive symptoms in the following, this means that the GDS-15 score was <6. An association between history of depression in general irrespective of onset age, early-onset depression, or late-onset depression without current depressive symptoms and subsequent dementia suggests that depression is a risk factor for dementia. An association between higher ages of depression onset with current depressive symptoms and subsequent dementia suggests that depression is a prodromal state of dementia.

Assessment of dementia

Dementia assessment was based on the Structured Interview for Diagnosis of Dementia of Alzheimer type, multi-infarct dementia and dementia of other aetiology according to DSM-IV and ICD-10 criteria (SIDAM; Zaudig & Hiller, Reference Zaudig and Hiller1996), which includes the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE; Folstein et al. Reference Folstein, Folstein and McHugh1975) implemented by a trained research assistant. In addition, each case of incident dementia and its aetiological subtype was validated by a neurological expert on the basis of medical information relevant to the aetiology of dementia (e.g. presence or absence of Parkinson's disease, stroke, or alcohol abuse) provided by a GP. AD was diagnosed according to DSM-IV criteria (APA, 1994). Vascular dementia was diagnosed according to NINDS-AIREN criteria (Roman et al. Reference Roman, Tatechimi, Erkinjuntii, Cummings, Masdeu, Garcia, Amaducci, Orgogozo, Brun and Hofman1993). Ambiguous cases were discussed by a group of three neurological experts in order to reach a consensus diagnosis. Target variables were all-cause dementia that included all cases of dementia, AD, and dementia of other aetiology (i.e. mixed forms, vascular dementia, specific types of dementia such as Lewy body dementia, or dementia caused by substance abuse, and dementia not otherwise specified) until follow-up 4. Presence or absence of dementia was diagnosed at every follow-up assessment. To avoid over- or underestimation of the time until dementia was manifest, the onset of incident dementia was estimated by dividing the time between the last dementia-free follow-up assessment and the follow-up assessment when dementia was first diagnosed in addition to all dementia-free follow-ups before. For example, if dementia was first diagnosed in follow-up 2, we estimated the midpoint of the interval between follow-up 1 and follow-up 2 and added this value to the time until follow-up 1 to obtain the time until dementia onset.

Measures of cognition

The German version of MMSE (Folstein et al. Reference Folstein, Folstein and McHugh1975) was used to measure global cognitive functioning in an objective manner. Subjective memory impairment was assessed as a subjectively rated measure of cognitive functions by asking ‘Do you feel like your memory is becoming worse?’ according to Geerlings et al. (Reference Geerlings, Jonker, Bouter, Adèr and Schmand1999). Possible answers were ‘no’, ‘yes, but this does not worry me’, and ‘yes, this worries me’. We used two (no/yes) and three (no/yes without worries/yes with worries) groups of subjective memory impairment as predictors to disentangle its affective and cognitive component. Subjective memory complaints with worries might be an expression of general depression/anxiety or an independent early cognitive predictor of subsequent dementia.

Covariates and statistical analysis

Cox regression analyses were used to investigate the effect of depression parameters and covariates assessed in follow-up 1 on the time until dementia was diagnosed in crude and adjusted proportional hazards models. Relevant depression parameters were determined by inspecting their crude hazard ratios. Depression parameters that did not significantly predict subsequent dementia were disregarded in the adjusted models. Kaplan–Meier survival curves and log-rank test were compared for participants with and without combined very late-onset depression and current depressive symptoms. Adjusted hazard ratios were computed in a three-stage approach. As cognitive measures are not merely control variables but are actually inherently associated with depression, they were entered separately in a second and third step. As the first step, we entered age in years at follow-up 1, sex, education according to CASMIN (König et al. Reference König, Lüttinger and Müller1988) in three stages, and dichotomous apolipoprotein E4 status (ApoE4; present or absent) as additional covariates to the depression parameters into our models to predict later dementia. In a second step, we added subjective memory impairment in two groups (no/yes) and the MMSE score as additional covariates into our models. In a third step, we added subjective memory impairment in three groups (no/yes without worries/yes with worries) and the MMSE score into our models. Two-sided t tests for independent samples were used to compare quantitative measures in different groups. Level of significance was set to α = 0.05. The Bonferroni method was used to correct for multiple univariate comparisons.

Results

At follow-up 1, information about history of depression was available for 2663 subjects (see Table 1). Of these participants, 238 (8.9%) subjects reported a history of depression. A total of 139 (5.2%) participants reported an early-onset up to age 59 years and 96 (3.6%) participants reported a late-onset beginning at ⩾60 years; for three (0.1%) participants this information was missing. At the same time, 306/2663 subjects (11.5%) reported depressive symptoms indicated by a GDS-15 score of ⩾6. Subjects with a history of depression reported more depressive symptoms than subjects without a history of depression (t 255.74 = − 8.83, p < 0.001). When we distinguished between history of early-onset depression up to age 59 years (t 144.93 = − 5.64, p < 0.001; mean = 3.84, s.d. = 3.32) and late-onset depression from age ⩾60 years (t 97.72 = − 7.12, p < 0.001; mean = 4.91, s.d. = 3.65), we found higher depressive symptoms measured by the continuous GDS-15 score in both groups compared to subjects without a history of depression (mean = 2.24, s.d. = 2.18).

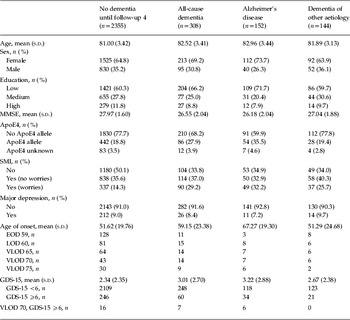

Table 1. Sample characteristics with status of dementia diagnosis until follow-up 4 and status of predictors at follow-up 1

MMSE, Mini-Mental Status Examination (Folstein et al. Reference Folstein, Folstein and McHugh1975); ApoE4, apolipoprotein E4; SMI, subjective memory impairment; GDS-15, Short Geriatric Depression Scale (Sheikh & Yesavage, Reference Sheikh, Yesavage and Brink1986); EOD 59, early-onset depression before age 60 years; LOD 60, late-onset depression from age ⩾60 years; VLOD, very late-onset depression with different cut-off ages; GDS-15, Short Geriatric Depression Scale (Sheikh & Yesavage, Reference Sheikh, Yesavage and Brink1986), dichotomized by 6; VLOD 70, GDS-15 ⩾6, combined very late-onset depression with age 70 years as cut-off and GDS-15 ⩾6.

Classification of education according to CASMIN (König et al. Reference König, Lüttinger and Müller1988).

There were 308 (11.6%) cases of incident dementia between follow-up 1 and follow-up 4. AD constituted 49.4% (n = 152) and dementia of other aetiology constituted 46.8% (n = 144; comprising 51 cases of mixed forms, 56 cases of vascular dementia, 16 cases of specific type of dementia and 21 cases of dementia not otherwise specified). Cases of dementia of other aetiology were analysed together due to the rather small specific sample sizes. For 3.9% (n = 12), the specific diagnosis of dementia remained unknown. Two-sided t tests for independent samples showed that participants with subsequent all-cause dementia (t 357.00 = 11.67, p < 0.001), subsequent AD (t 162.10 = 10.52, p < 0.001), and subsequent dementia of other aetiology (t 155.97 = 5.73, p < 0.001) had lower MMSE scores than participants without any diagnosis of later dementia at follow-up 1.

Analyses of different cut-offs for late-onset depression

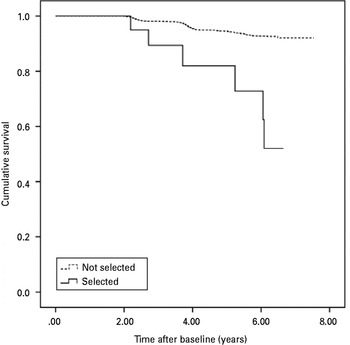

Major depression per se was not associated with subsequent dementia (see Table 2). Age of depression onset as a continuous variable was marginally significant for all-cause dementia, significant for AD, but not significant for dementia of other aetiology. Two-sided t tests revealed only a marginally different mean age of onset in subjects with and without all-cause dementia (t 233 = − 1.80, p = 0.074) driven by a different mean age of onset in subjects with and without AD (t 218 = − 2.56, p = 0.011) and no different mean age of onset in subjects with and without dementia of other aetiology (t 221 = 0.60, p = 0.952). When we entered age of depression onset as a dichotomized variable, we used the Bonferroni method to correct for multiple comparisons and found an increase of dementia risk for higher depression cut-off ages. Crude hazard ratios for all-cause dementia were not significant for early-onset depression and late-onset depression with a 60 and 65 years cut-off. The risk for all-cause dementia was significantly increased, when very late-onset depression at age 70 years was diagnosed. Results for AD were similar, but hazard ratios of very late-onset depression were higher, only significant for a 75 years cut-off and we found a marginal risk reduction of early-onset depression for AD. In dementia of other aetiology than AD, there was no increased risk for subsequent dementia when very late-onset depression cut-offs were chosen. Subjects with a very late-onset of depression from age ⩾70 years and current depressive symptoms that were indicated by a dichotomized GDS-15 score had a greater than threefold risk for later all-cause dementia. The increased risk for dementia was exclusively driven by the greater than sixfold risk for later AD. As we obtained similar results for the 70 and 75 years cut-offs of late-onset depression, we decided to use the 70 years cut-off for further analyses, which included more cases. Depressive symptoms significantly increased the risk for later all-cause dementia, AD, and dementia of other aetiology. Fig. 2 shows Kaplan–Meier survival curves for AD by very late-onset of depression with current depressive symptoms. The log-rank test indicated a significant difference between subjects with combined very late-onset depression from ⩾70 years and current depressive symptoms and subjects without a combined history of depression and current depressive symptoms (χ 21 = 26.40, p < 0.001).

Fig. 2. Kaplan–Meier survival curves of time to incidence of Alzheimer's disease by very late-onset of depression (⩾70 years) with current depressive symptoms.

Table 2. Depression parameters and risk for subsequent dementia

HR, Hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; age of onset = age of depression onset as continuous variable; EOD 59, early-onset depression before age 60 years; LOD 60, late-onset depression from age ⩾60 years;. VLOD, very late-onset depression with different cut-off ages; GDS-15 dichotomized, cut-off score ⩾6.

Level of significance according to Bonferroni correction for LOD 60/VLOD 65/VLOD 70/VLOD 75: α = 0.0125 and for VLOD 70, GDS 15 ⩾6/VLOD 75, GDS 15 ⩾6: α = 0.025.

*** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05, † p < 0.10.

Adjusted models of dementia risk

As a first step, we entered common control variables (age, sex, education, ApoE4) and the depression parameters (very late-onset of major depression, depressive symptoms as a dichotomized variable) into the adjusted hazard ratio models (see Table 3). When very late-onset major depression and depressive symptoms were separately entered into the adjusted models, they both increased the risk for later all-cause dementia. Only the dichotomized GDS-15 score increased the risk for later AD. The hazard ratios' magnitude of very late-onset depression remained similar, but was no longer significant. Dementia of other aetiology was only marginally predicted by very late-onset depression and elevated depressive symptoms. When we entered very late-onset depression and GDS-15 score combined (i.e. subjects that had very late-onset depression with current depressive symptoms) into our models, we found an even higher risk for later all-cause dementia that was exclusively driven by an increased risk for later AD.

Table 3. Risk for dementia under consideration of different covariates (age, sex, education, ApoE4), cognition (MMSE, subjective memory impairment) and depression measures (very late-onset depression and depressive symptoms separately in model 1 and combined in model 2)

HR, Hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; VLOD 70, very late-onset depression with age 70 years as cut-off; GDS-15 ⩾6, Short Geriatric Depression Scale (Sheikh & Yesavage, Reference Sheikh, Yesavage and Brink1986) score dichotomized by 6; VLOD 70, GDS-15 ⩾6, combined very late-onset depression with age 70 years as cut-off and GDS-15 ⩾6; MMSE, Mini-Mental Status Examination (Folstein et al. Reference Folstein, Folstein and McHugh1975); SMI, subjective memory impairment.

All models adjusted for age, sex, level of education, and ApoE4.

*** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05, † p < 0.10.

As a second step, we checked if the association between depression and dementia remained after entering cognitive measures [i.e. MMSE, subjective memory impairment (no/yes); see Table 3]. When entered separately, the dichotomized GDS-15 score increased the risk for later all-cause dementia and AD but not the risk for dementia of other aetiology. Very late-onset depression only marginally increased the risk for all-cause dementia and dementia of other aetiology. Again, very late-onset depression starting at age 70 years with current depressive symptoms as indicated by the dichotomized GDS-15 score was most predictive and the association was exclusively driven by a greater than threefold risk for later AD.

When we entered subjective memory impairment as a variable of three groups (no subjective memory impairment, subjective memory impairment without and with worries), depression parameters did not predict any type of dementia except a marginal relationship between current depressive symptoms and all-cause dementia and between very late-onset depression and dementia of other aetiology (see Table 3). Subjective memory impairment with worries more than doubled the risk for all-cause dementia, AD, and dementia of other aetiology.

Discussion

Early-onset depression or depression in general was not associated with time to conversion to dementia. Later onset of depression was associated with an increased risk for all-cause dementia driven by an increased risk for subsequent AD. When we entered very late-onset depression and depressive symptoms separately into the adjusted models, very late-onset depression did not predict subsequent dementia, but a combination of very late-onset depression and currently elevated depressive symptoms of clinical relevance, possibly reflecting depression without remission, was predictive for subsequent dementia. This association was exclusively driven by an increased risk for later AD. Currently elevated depressive symptoms entered separately into our adjusted models were associated with subsequent all-cause dementia and AD, but not with dementia of other aetiology.

In further analysis we found that subjective memory impairment with worries fully mediated the association between combined and separately entered depression parameters and subsequent dementia which might suggest that depression emerged as a consequence of a worrisome insight into cognitive deterioration. Thereby, this study provides further evidence for the predictive power of subjective memory impairment in subsequent dementia, especially in AD.

The present study suggests that depression is a prodromal feature of AD rather than a risk factor for it because we found that very late-onset depression in combination with current depressive symptoms was most predictive. We did not find that depression in general or very late-onset depression independent of current depressive symptoms was associated with an increased risk for subsequent dementia, but this association would be expected if depression is a risk factor. Prediction of AD by the combination of very late-onset depression and current depressive symptoms was independent of objective cognition. Hence, clinicians should consider cognitive and depressive measures, as they do not seem to be redundant but independently predicted later AD. Subjective memory impairment is interconnected with depression, it predicted subsequent dementia of all types in our study, and can be assessed in a very economical way. Thus, clinicians should enquire about the memory complaints of patients and take them seriously.

The insidious onset of AD might explain the stronger relationship with depression parameters. Our finding that late-onset depression was associated with an increased risk for subsequent dementia is in accord with recent studies (Brommelhoff et al. Reference Brommelhoff, Gatz, Johansson, McArdle, Fratiglioni and Pedersen2009; Li et al. Reference Li, Wang, Shofer, Thompson, Peskind, McCormick, Bowen, Crane and Larson2011). In accordance with Gatz et al. (Reference Gatz, Tyas, St. John and Montgomery2005), we found that clinically relevant depressive symptoms predicted later AD. Gatz et al. (Reference Gatz, Tyas, St. John and Montgomery2005) did not investigate the age of depression onset, which may explain their null finding as history of depression per se was not associated with later dementia, as in our study. In another study, depressive symptoms, but not self-reported history of depression, predicted development of vascular dementia, but not AD (Lenoir et al. Reference Lenoir, Dufouil, Auriacombe, Lacombe, Dartigues, Ritchie and Tzourio2011). These results are contrary to our findings, although we did not differentiate between dementia diagnoses other than AD because the resulting groups would have been too small. Nonetheless, when we used age 60 years as the cut-off for late-onset depression, we failed to find an association with later dementia as well. Hence, divergent results regarding history of depression might in part emerge from different cut-offs for late-onset depression.

Early-onset major depression up to age 59 years was not associated with later all-cause dementia, whereas it was marginally related to a reduced risk of later AD. It can be argued that this result endangers the validity of the association between very late-onset depression and later AD. Because of the retrospective assessment of depression onset, recall bias might have lowered report rates of depression in the complete sample and in pre-dementia or pre-AD subjects in particular. We now give a number of reasons that might counter the argument of deficient validity concerning our data on major depression, although these reasons cannot rule out that argument completely. We excluded subjects with a diagnosis of dementia at baseline or follow-up 1 and entered objective cognitive status at follow-up 1 as a covariate into our adjusted models. Additionally, a specific recall bias in subjects with later dementia is less likely because of rather high mean MMSE scores in follow-up 1, but cannot be discounted because the global cognition score was already impaired in follow-up 1 (especially for AD) compared to participants without dementia. Otherwise, global cognition scores were reduced in AD and in dementia of other aetiology as well, so that an effect of impaired memory due to dementia cannot explain the specific association between very late-onset depression and AD because it should also have affected age of depression onset in dementia of other aetiology, which was not the case. Barnes et al. (Reference Barnes, Yaffe, McCormick, Schaefer, Quesenberry, Byers and Whitmer2010) assessed mid- and late-life depression variables not retrospectively, but at different measurement points and found that late-life depression was strongly associated with AD, whereas chronic depression in mid- and late-life was strongly associated with vascular dementia. Another study (Brommelhoff et al. Reference Brommelhoff, Gatz, Johansson, McArdle, Fratiglioni and Pedersen2009) that used register-based depression history unaffected by possible recall bias also found that depression was a prodromal feature of dementia and AD rather than a risk factor. If subjects who subsequently developed dementia are more likely to forget depressive episodes in earlier life, hazard ratios for early-onset depression should be significantly decreased, which was not the case.

Our results could be questioned because lifetime prevalence of depression was rather low, but there are some reasons that might explain this. Rates of major depression might be smaller than expected because of the suggested higher mortality in depressive persons compared to non-depressive subjects (Blazer, Reference Blazer2003). Others (Andrade et al. Reference Andrade, Caraveo-Anduaga, Berglund, Bijl, de Graaf, Vollebergh, Dragomirecá, Kohn, Keller, Kessler, Kawakami, Kilic, Offord, Üstün and Wittchen2003; Kessler et al. Reference Kessler, Berglund, Demler, Jin, Koretz, Merikangas, Rush, Walters and Wang2003) have already documented a lower lifetime prevalence of major depressive episodes in older birth cohorts compared to younger ones. Kessler et al. (Reference Kessler, Berglund, Demler, Jin, Merikangas and Walters2005) reported a lifetime prevalence of major depressive disorder of 10.6% for a cohort aged ⩾60 years which appears comparable to our rate of 8.9% in a cohort aged ⩾75 years. In summary, recall bias might account for the smaller than expected rate of depression but does not entirely explain our specific result that very late-onset depression is a likely prodrome of AD but not of dementia of other aetiology.

Our study has several strengths such as its longitudinal design and an extensive assessment of cognitive and psychiatric variables in a large sample. Associations with control variables (i.e. ApoE4 genotype) underpinned the validity of dementia diagnoses. We assessed psychiatric diagnosis and symptoms of depression with an instrument that was designed for geriatric samples. As somatic symptoms, death concerns, or loss of sexual interest in the elderly may be part of normal ageing or physical illness instead of depression, the GDS refers to it to a lesser extent than other self-report depression scales (Montorio & Izal, Reference Montorio and Izal1996; Arthur et al. Reference Arthur, Jagger, Lindesay, Graham and Clarke1999). We used Bonferroni correction which is a conservative method to deal with the problem of multiple comparisons when we investigated different age cut-offs for very late-onset depression and found an increased risk for subsequent all-cause dementia in participants with very late-onset depression from age ⩾70 years.

Besides these strengths, there are also some limitations of our study. Our results refer to cases of late-life dementia and cannot be applied to cases of dementia with onset at younger ages. We only assessed major depression and disregarded minor depression and dysthymia. Although we assessed major depression following CIDI, our standardized interview was partly abbreviated and modified as already reported in the Method section. Depression and dementia can ‘overlap’ in the elderly so that it can be difficult to disentangle them. They either can be concurrent risk factors (i.e. persons with depression are less likely to be diagnosed as demented) or show similar clinical appearance (i.e. depressed persons are ‘wrongly’ diagnosed as demented). In the literature, the later phenomenon used to be called ‘pseudo-dementia’ (Korczyn & Halperin, Reference Korczyn and Halperin2009). Another limitation of our study is the rather short period of follow-up assessment.

Generalizability might be limited by the fact that our results refer to a subgroup of 23 participants with combined very-late onset depression and current depressive symptoms that make up <1% of the whole sample. Thus, a criticism of our results could be that they are based only on a fraction of the sample. On the other hand, those who are part of this small subpopulation show a significantly increased risk for later AD.

As the development of dementia and especially AD can be a long-lasting process (e.g. Amieva et al. Reference Amieva, Le Goff, Millet, Orgogozo, Pérès, Barberger-Gateau, Jacqmin-Gadda and Dartigues2008), the prodromal association between depression and dementia might even be underestimated in the present study due to false-negative cases of dementia. Our assumptions to distinguish between depression as a prodrome of and as a risk factor for later dementia seem plausible but might undermine that close temporal proximity and persistent depressive symptoms do not completely eliminate the second interpretation. The distinction of a risk factor for and a prodromal state of a disease is hindered by the fact that the disease might not be identified at the beginning.

In addition to these limitations that specifically apply to our study, there are some general problems of longitudinal studies such as a positive selection bias when participants were recruited and sample attrition because some participants were lost due to a number of reasons in the course of the follow-ups. The sample might not be representative of the general population as only GP-registered patients were considered at enrolment and might not be representative of other populations of elderly individuals, as they are survivors of the Second World War. Future research that includes prospective assessment in community samples and starts from early adulthood could reduce recall bias of depressive episodes.

In sum, we have provided new evidence suggesting that depression is a prodromal state of subsequent dementia and AD rather than a risk factor for it because the combination of very late-onset depression and current depressive symptoms was most predictive independently of objective cognitive functions. The association was mediated by worrying subjective memory impairment. Thus, very late-onset depression with persistent symptomatology that is based on worrisome subjective memory impairment in the elderly might deserve close neuropsychological monitoring.

Appendix. Members of the AgeCoDe Study Group

Principal investigators: Wolfgang Maier, Martin Scherer, Hendrik van den Bussche (2002–2011)

Heinz-Harald Abholz, Cadja Bachmann, Horst Bickel, Wolfgang Blank, Hendrik van den Bussche, Sandra Eifflaender-Gorfer, Marion Eisele, Annette Ernst, Angela Fuchs, Kathrin Heser, Frank Jessen, Hanna Kaduszkiewicz, Teresa Kaufeler, Mirjam Köhler, Hans-Helmut König, Alexander Koppara, Carolin Lange, Hanna Leicht, Tobias Luck, Melanie Luppa, Manfred Mayer, Edelgard Mösch, Julia Olbrich, Michael Pentzek, Jana Prokein, Anna Schumacher, Steffi Riedel-Heller, Janine Stein, Susanne Steinmann, Franziska Tebarth, Michael Wagner, Klaus Weckbecker, Dagmar Weeg, Jochen Werle, Siegfried Weyerer, Birgitt Wiese, Steffen Wolfsgruber, Thomas Zimmermann.

GPs participating at the time of follow-up 5

Bonn: Claudia Adrian, Hanna Liese, Inge Bürfent, Johann von Aswege, Wolf-Dietrich Honig, Peter Gülle, Heribert Schützendorf, Elisabeth Benz, Annemarie Straimer, Arndt Uhlenbrock, Klaus-Michael Werner, Maria Göbel-Schlatholt, Hans-Jürgen Kaschell, Klaus Weckbecker, Theodor Alfen, Markus Stahlschmidt, Klaus Fischer, Wolf-Rüdiger Weisbach, Martin Tschoke; Jürgen Dorn, Helmut Menke, Erik Sievert, Ulrich Kröckert, Gabriele Salingré, Christian Mörchen, Peter Raab, Angela Baszenski, Clärli Loth, Christian Knaak, Peter Hötte, Jörg Pieper, Dirk Wassermann, Hans Josef Leyendecker, Gerhard Gohde, Barbara Simons, Achim Brünger, Uwe Petersen, Heike Wahl, Rainer Tewes, Doris Junghans-Kullmann, Angela Grimm-Kraft, Harald Bohnau, Ursula Pinsdorf, Thomas Busch, Gisela Keller, Susanne Fuchs-Römer, Wolfgang Beisel.

Düsseldorf: Birgitt Richter-Polynice, Florinela Cupsa, Roland Matthias Unkelbach, Gerhard Schiller, Barbara Damanakis, Michael Frenkel, Klaus-Wolfgang Ebeling, Pauline Berger, Kurt Gillhausen, Uwe Hellmessen, Helga Hümmerich, Hans-Christian Heede, Boguslaw-Marian Kormann, Wolfgang Josef Peters, Ulrich Schott, Dirk Matzies, Andre Schumacher, Tim Oliver Flettner, Winfried Thraen, Harald Siegmund, Claus Levacher, Tim Blankenstein, Eliane Lamborelle, Ralf Hollstein, Edna Hoffmann, Ingeborg Ghane, Regine Claß, Stefan-Wolfgang Meier, Leo W. Moers, Udo Wundram, Klaus Schmitt, Rastin Missghian, Karin Spallek und Christiane Schlösser.

Hamburg: Kathrin Groß, Winfried Bouché, Ursula Linn, Gundula Bormann, Gerhard Schulze, Klaus Stelter, Heike Gatermann, Doris Fischer-Radizi, Otto-Peter Witt, Stefanie Kavka, Günther Klötzl, Karl-Christian Münter, Michael Baumhöfener, Maren Oberländer, Cornelia Schiewe, Jörg Hufnagel, Anne-Marei Kressel, Michael Kebschull, Christine Wagner, Fridolin Burkhardt, Martina Hase, Matthias Büttner, Karl-Heinz Houcken, Christiane Zebidi, Johann Bröhan, Christiane Russ, Frank Bethge, Gisela Rughase-Block, Margret Lorenzen, Arne Elsen, Lerke Stiller, Angelika Giovanopoulos, Daniela Korte, Ursula Jedicke, Rosemarie Müller-Mette, Andrea Richter, Sanna Rauhala-Parrey, Constantin Zoras, Gabriele Pfeil-Woltmann, Annett Knöppel-Frenz, Martin Kaiser, Johannes Bruns, Joachim Homann, Georg Gorgon, Niklas Middendorf, Kay Menschke, Hans Heiner Stöver, Hans H. Bayer, Rüdiger Quandt, Gisela Rughase-Block, Hans-Michael Köllner, Enno Strohbehn, ThomasHaller, Nadine Jesse, Martin Domsch, Marcus Dahlke.

Leipzig: Thomas Lipp, Ina Lipp, Martina Amm, Horst Bauer, Gabriele Rauchmaul, Hans Jochen Ebert, Angelika Gabriel-Müller, Hans-Christian Taut, Hella Voß, Ute Mühlmann, Holger Schmidt, Gabi Müller, Eva Hager, Bettina Tunze, Barbara Bräutigam, Thomas Paschke, Heinz-Michael Assmann, Ina Schmalbruch, Gunter Kässner, Iris Pförtzsch, Brigitte Ernst-Brennecke, Uwe Rahnefeld, Petra Striegler, Marga Gierth, Anselm Krügel, Margret Boehm, Dagmar Harnisch, Simone Kornisch-Koch, Birgit Höne, Lutz Schönherr, Frank Hambsch, Katrin Meitsch, Britta Krägelin-Nobahar, Cornelia Herzig, Astrid Georgi, Erhard Schwarzmann, Gerd Schinagl, Ulrike Pehnke, Mohammed Dayab, Sabine Müller, Jörg-Friedrich Onnasch, Michael Brosig, Dorothea Frydetzki, Uwe Abschke, Volkmar Sperling, Ulrich Gläser, Frank Lebuser, Detlef Hagert.

Mannheim: Gerhard Arnold, Viet-Harold Bauer, Hartwig Becker, Hermine Becker, Werner Besier, Hanna Böttcher-Schmidt, Susanne Füllgraf-Horst, Enikö Göry, Hartmut Grella, Hans Heinrich Grimm, Petra Heck, Werner Hemler, Eric Henn, Violetta Löb, Grid Maaßen-Kalweit, Manfred Mayer, Hubertus Mühlig, Arndt Müller, Gerhard Orlovius, Helmut Perleberg, Brigitte Radon, Helmut Renz, Carsten Rieder, Michael Rosen, Georg Scheer, Michael Schilp, Angela Schmid, Matthias Schneider, Christian Schneider, Rüdiger Stahl, Christian Uhle, Jürgen Wachter, Necla Weihs, Brigitte Weingärtner, Monika Werner, Hans-Georg Willhauck, Eberhard Wochele, Bernhard Wolfram.

München: Andreas Hofmann, Eugen Allwein, Helmut Ruile, Andreas Koeppel, Peter Dick, Karl-Friedrich Holtz, Gabriel Schmidt, Lutz-Ingo Fischer, Johann Thaller, Guntram Bloß, Franz Kreuzer, Günther Holthausen, Karl Ludwig Maier, Walter Krebs, Christoph Mohr, Heinz Koschine, Richard Ellersdorfer, Michael Speth, Maria Kleinhans, Panagiota Koutsouva-Sack, Gabriele Staudinger, Johann Eiber, Stephan Thiel, Cornelia Gold, Andrea Nalbach, Kai Reichert, Markus Rückgauer, Martin Neef, Viktor Fleischmann, Natalija Mayer, Andreas Spiegl, Fritz Renner, Eva Weishappel-Ketisch, Thomas Kochems, Hartmut Hunger, Marianne Hofbeck, Alfred Neumeier, Elfriede Goldhofer, Thomas Bommer, Reinhold Vollmuth, Klaus Lanzinger, Simone Bustami-Löber, Ramona Pauli, Jutta Lindner, Gerlinde Brandt, Otto Hohentanner, Rosita Urban-Hüttner, Peter Porz, Bernd Zimmerhackl, Barbara Naumann, Margarete Vach, Alexander Hallwachs, Claudia Haseke, Andreas Ploch, Paula Bürkle-Grasse, Monika Swobodnik, Corina Tröger, Detlev Jost, Roman Steinhuber, Renate Narr, Gabriele Nehmann-Hörwick, Christiane Eder, Helmut Pillin, Frank Loth, Beate Rücker, Nicola Fritz, Michael Rafferzeder, Dietmar Zirpel.

GPs who participated at baseline

Bonn: Heinz-Peter Romberg, Hanna Liese, Inge Bürfent, Johann von Aswege, Wolf-Dietrich Honig, Peter Gülle, Heribert Schützendorf, Manfred Marx, Annemarie Straimer, Arndt Uhlenbrock, Klaus-Michael Werner, Maria Göbel-Schlatholt, Eberhard Prechtel, Hans-Jürgen Kaschell, Klaus Weckbecker, Theodor Alfen, Jörg Eimers-Kleene, Klaus Fischer, Wolf-Rüdiger Weisbach, Martin Tschoke.

Düsseldorf: Birgitt Richter-Polynice, Michael Fliedner, Binjamin Hodgson, Florinela Cupsa, Werner Hamkens, Roland Matthias Unkelbach, Gerhard Schiller, Barbara Damanakis, Angela Ackermann, Michael Frenkel, Klaus-Wolfgang Ebeling, Bernhard Hoff, Michael Kirsch, Vladimir Miasnikov, Pauline Berger, Kurt Gillhausen, Uwe Hellmessen, Helga Hümmerich, Hans-Christian Heede, Boguslaw-Marian Kormann, Dieter Lüttringhaus, Wolfgang Josef Peters, Ulrich Schott, Dirk Matzies, Andre Schumacher, Tim Oliver Flettner, Winfried Thraen, Clemens Wirtz, Harald Siegmund.

Hamburg: Kathrin Groß, Bernd-Uwe Krug, Petra Hütter, Dietrich Lau, Gundula Bormann, Ursula Schröder-Höch, Wolfgang Herzog, Klaus Weidner, Doris Fischer-Radizi, Otto-Peter Witt, Stefanie Kavka, Günther Klötzl, Ljudmila Titova, Andrea Moritz.

Leipzig: Thomas Lipp, Ina Lipp, Martina Amm, Horst Bauer, Gabriele Rauchmaul, Hans Jochen Ebert, Angelika Gabriel-Müller, Hans-Christian Taut, Hella Voß, Ute Mühlmann, Holger Schmidt, Gabi Müller, Eva Hager, Bettina Tunze, Barbara Bräutigam, Sabine Ziehbold, Thomas Paschke, Heinz-Michael Assmann, Ina Schmalbruch, Gunter Kässner.

Mannheim: Gerhard Arnold, Viet-Harold Bauer, Werner Besier, Hanna Böttcher-Schmidt, Hartmut Grella, Ingrid Ludwig, Manfred Mayer, Arndt Müller, Adolf Noky, Gerhard Orlovius, Helmut Perleberg, Carsten Rieder, Michael Rosen, Georg Scheer, Michael Schilp, Gerhard Kunzendorf, Matthias Schneider, Jürgen Wachter, Brigitte Weingärtner, Hans-Georg Willhauck.

München: Helga Herbst, Andreas Hofmann, Eugen Allwein, Helmut Ruile, Andreas Koeppel, Peter Friedrich, Hans-Georg Kirchner, Elke Kirchner, Luitpold Knauer, Peter Dick, Karl-Friedrich Holtz, Elmar Schmid, Gabriel Schmidt, Lutz-Ingo Fischer, Johann Thaller, Guntram Bloß, Franz Kreuzer, Ulf Kahmann, Günther Holthausen, Karl Ludwig Maier, Walter Krebs, Christoph Mohr, Heinz Koschine, Richard Ellersdorfer, Michael Speth.

GPs who previously participated in the study

Bonn: Heinz-Peter Romberg, Eberhard Prechtel, Manfred Marx, Jörg Eimers-Kleene, Paul Reich, Eberhard Stahl, Reinhold Lunow, Klaus Undritz, Bernd Voss, Achim Spreer, Oliver Brenig, Bernhard G. Müller, Ralf Eich, Angelika Vossel, Dieter Leggewie, Angelika Schmidt, Nahid Aghdai-Heuser, Lutz Witten, Michael Igel.

Düsseldorf: Michael Fliedner, Benjamin Hodgson, Werner Hamkens, Angela Ackermann, Bernhard Hoff, Michael Kirsch, Vladimir Miasnikov, Dieter Lüttringhaus, Clemens Wirtz, Rolf Opitz, Jürgen Bausch, Dirk Mecking, Friederike Ganßauge, Elmar Peters, Alfons Wester.

Hamburg: Werner Petersen, Martin Daase, Martin Rüsing, Christoph von Sethe, Wilmhard Borngräber, Brigitte Colling-Pook, Ullrich Weidner, Peter Rieger, Lutz Witte, Hans-Wilhelm Busch, Jürgen Unger, Angela Preis, Michael Mann, Ernst Haeberle, Horst Köhler, Ruth Schäfer, Helmut Sliwiok, Volker L. Brühl, Hans-Heiner Stöver, Harald Deest, Margret Ackermann-Körner, Dieter Reinstorff, Christamaria Schlüter, Henrik Heinrichs, Ole Dankwarth, Michael Böse, Ulricke Ryll, Reinhard Bauer, Dieter Möltgen, Sven Schnakenbeck, Karin Beckmann, Annegret Callsen, Ewa Schiewe, Holger Gehm, Volker Lambert, Karin Hinkel-Reineke, Carl-Otto Stolzenbach, Peter Berdin, Friedhelm Windler.

Leipzig: Sabine Ziehbold, Sabine Weidnitzer, Erika Rosenkranz, Norbert Letzien, Doris Klossek, Martin Liebsch, Andrea Zwicker, Ulrike Hantel, Monika Pilz, Volker Kirschner, Rainer Arnold, Ulrich Poser.

Mannheim: Wolfgang Barthel, Fritz Blechinger, Marcus Fähnle, Reiner Walter Fritz, Susanne Jünemann, Gabriele Kirsch, Jürgen Kulinna, Gerhard Kunzendorf, Andreas Legner-Görke, Christa Lehr, Wolfgang Meer, Adolf Noky, Christina Panzer, Achim Raabe, Helga Schmidt-Back, Ralf Schürmann, Hans-Günter Stieglitz, Marie-Luise von der Heide.

München: Helga Herbst, Peter Friedrich, Hans-Georg Kirchner, Elke Kirchner, Luitpold Knauer, Elmar Schmid, Ulf Kahmann, Jörg Kastner, Ulrike Janssen, Albert Standl, Clemens Göttl, Marianne Franze, Gerhard Moser, Almut Blümm, Petra Weber, Wolfgang Poetsch, Heinrich Puppe, Thomas Bommer, Gerd Specht, Leonard Badmann, May Leveringhaus, Michael Posern, Andreas Ploch, Ralph Potkowski, Christiane Eder, Michael Schwandner, Rudolf Weigert, Christoph Huber.

Acknowledgements

We thank all participating patients and their general practitioners for their good collaboration.

This study/publication is part of the German Research Network on Dementia (KND) and the German Research Network on Degenerative Dementia (KNDD) and was funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (grants KND: 01GI0102, 01GI0420, 01GI0422, 01GI0423, 01GI0429, 01GI0431, 01GI0433, 01GI0434; grants KNDD: 01GI0710, 01GI0711, 01GI0712, 01GI0713, 01GI0714, 01GI0715, 01GI0716, 01ET1006B).

Declaration of Interest

None.