Introduction

Anorexia nervosa (AN) is one of the most common chronic disorders in adolescence, with incidence rates at least as high as that of type 1 diabetes (Gonzalez et al. Reference Gonzalez, Kohn and Clarke2007). It affects up to 4% of women during their lifetime (Keski-Rahkonen & Mustelin, Reference Keski-Rahkonen and Mustelin2016). The peak age of onset of AN is from age 15 to 19, i.e. at a developmentally sensitive time (Micali et al. Reference Micali, Hagberg, Petersen and Treasure2013). Average illness duration is about 6 years. Whilst overall the incidence of AN is thought to be stable in Western countries (Keski-Rahkonen & Mustelin, Reference Keski-Rahkonen and Mustelin2016), improved detection may have contributed to reported increases in rates and decreases in age of onset noted in some studies (Steinhausen & Jensen, Reference Steinhausen and Jensen2015). Core symptoms of AN include persistent severe food restriction, especially of high caloric foods, leading to significant underweight. In a proportion of cases, there are episodes of loss-of-control or binge eating. Associated weight control behaviours (such as excessive exercise, self-induced vomiting, laxative abuse) are driven by an extreme fear of food, eating or weight gain. Psychological and physical comorbidities are common, and the mortality rate is the highest of any mental disorder (Treasure et al. Reference Treasure, Zipfel, Micali, Wade, Stice, Claudino, Schmidt, Frank, Bulik and Wentz2015c; Schmidt et al. Reference Schmidt, Adan, Böhm, Campbell, Dingemans, Ehrlich, Elzakkers, Favaro, Giel, Harrison, Himmerich, Hoek, Herpertz-Dahlmann, Kas, Seitz, Smeets, Sternheim, Tenconi, van Elburg, van Furth and Zipfel2016a). In 15–24-year olds, the mortality risk is also higher than for other serious diseases in adolescence, such as asthma or type 1 diabetes (Hoang et al. Reference Hoang, Goldacre and James2014). Thus, the disease burden for patients, their caregivers and society is high (Schmidt et al. Reference Schmidt, Adan, Böhm, Campbell, Dingemans, Ehrlich, Elzakkers, Favaro, Giel, Harrison, Himmerich, Hoek, Herpertz-Dahlmann, Kas, Seitz, Smeets, Sternheim, Tenconi, van Elburg, van Furth and Zipfel2016a).

The aetiology of AN is complex, with evidence for multiple biopsychosocial risk and maintenance factors (Treasure et al. Reference Treasure, Zipfel, Micali, Wade, Stice, Claudino, Schmidt, Frank, Bulik and Wentz2015c; Zipfel et al. Reference Zipfel, Giel, Bulik, Hay and Schmidt2016). Data suggest that environmental and psychological factors interact with and influence the expression of genetic risk to cause eating pathology (Culbert et al. Reference Culbert, Racine and Klump2015). Increasingly, there is a broad acceptance of AN as a brain-based disorder and of neurobiological overlaps between AN, anxiety disorders and addictions (O'Hara et al. Reference O'Hara, Campbell and Schmidt2015). Neuroimaging studies have revealed differences in the structure and function of the brain in acute stage AN and in recovery. For example, systematic reviews in adolescents and adults have reported reduced grey and white matter volumes, increased cerebrospinal fluid and altered white matter structure in acute AN compared with healthy individuals (Martin Monzon et al. Reference Martin Monzon, Hay, Foroughi and Touyz2016; Seitz et al. Reference Seitz, Herpertz-Dahlmann and Konrad2016) with some changes persisting in recovery (Martin Monzon et al. Reference Martin Monzon, Hay, Foroughi and Touyz2016). In acute stage AN, functional differences have been observed in ventral limbic regions involved in the assignment of emotional significance to stimuli, arousal and generation of emotional responses (i.e. the amygdala, ventral striatum, insula, ventral anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), orbitofrontal cortex) and dorsal regions implicated in higher level evaluative cognitions (including the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), parietal cortex, dorsal ACC) (Kaye, Reference Kaye2008; Kaye et al. Reference Kaye, Fudge and Paulus2009, Reference Kaye, Wagner, Fudge and Paulus2011; Zhu et al. Reference Zhu, Hu, Wang, Chen, Guo, Li and Enck2012). As a result of these findings, differences in brain structure and function are being incorporated into aetiological models of eating disorders (EDs). In particular, researchers have implicated alterations in neural circuits involved in reward processing (Frank, Reference Frank2013; Wierenga et al. Reference Wierenga, Ely, Bischoff-Grethe, Bailer, Simmons and Kaye2014b; O'Hara et al. Reference O'Hara, Campbell and Schmidt2015; Wu et al. Reference Wu, Brockmeyer, Hartmann, Skunde, Herzog and Friederich2016), negative affect and stress (Connan et al. Reference Connan, Campbell, Katzman, Lightman and Treasure2003), appetite regulation (Kaye et al. Reference Kaye, Fudge and Paulus2009, Reference Kaye, Wagner, Fudge and Paulus2011), cognitive (self-regulatory) control (Zastrow et al. Reference Zastrow, Kaiser, Stippich, Walther, Herzog, Tchanturia, Belger, Weisbrod, Treasure and Friederich2009; Friederich et al. Reference Friederich, Wu, Simon and Herzog2013; Wierenga et al. Reference Wierenga, Bischoff-Grethe, Melrose, Grenesko-Stevens, Irvine, Wagner, Simmons, Matthews, Yau, Fennema-Notestine and Kaye2014a) and socio-emotional processes (Zhu et al. Reference Zhu, Hu, Wang, Chen, Guo, Li and Enck2012; McAdams & Smith, Reference McAdams and Smith2015).

Additionally, there is growing evidence to support a stage model of illness for AN, with neurobiological progression and some suggestion that outcomes become poorer once illness duration exceeds 3 years (Currin et al. Reference Currin, Schmidt, Treasure and Jick2005; Treasure et al. Reference Treasure, Stein and Maguire2015b; Schmidt et al. Reference Schmidt, Brown, McClelland, Glennon and Mountford2016b).

Available treatments are largely psychological and/or focus on nutritional rehabilitation (Hay, Reference Hay2013; Kass et al. Reference Kass, Kolko and Wilfley2013; Watson & Bulik, Reference Watson and Bulik2013; Hay et al. Reference Hay, Claudino, Touyz and Abd Elbaky2015; Zipfel et al. Reference Zipfel, Giel, Bulik, Hay and Schmidt2016). For adolescents with AN, there is clear evidence that ED-focused family therapy is superior to individual therapy and thus the treatment of choice (Hay et al. Reference Hay, Chinn, Forbes, Madden, Newton, Sugenor, Touyz and Ward2014; Zipfel et al. Reference Zipfel, Giel, Bulik, Hay and Schmidt2016). In contrast, for adults, there is no leading treatment, recovery rates are low to moderate, and attrition and relapse rates are high (Treasure et al. Reference Treasure, Zipfel, Micali, Wade, Stice, Claudino, Schmidt, Frank, Bulik and Wentz2015c; Zipfel et al. Reference Zipfel, Giel, Bulik, Hay and Schmidt2016). Evidence for the efficacy of any pharmacological treatments of AN (Aigner et al. Reference Aigner, Treasure, Kaye and Kasper2011; Flament et al. Reference Flament, Bissada and Spettigue2012; Hay & Claudino, Reference Hay and Claudino2012; Kishi et al. Reference Kishi, Kafantaris, Sunday, Sheridan and Correll2012; de Vos et al. Reference De Vos, Houtzager, Katsaragaki, van de Berg, Cuijpers and Dekker2014) is weak, with some studies finding olanzapine to show promise in reducing illness preoccupations and meal-time anxiety (Kishi et al. Reference Kishi, Kafantaris, Sunday, Sheridan and Correll2012; Lebow et al. Reference Lebow, Sim, Erwin and Murad2013; de Vos et al. Reference De Vos, Houtzager, Katsaragaki, van de Berg, Cuijpers and Dekker2014). This situation calls for the development of novel treatment approaches (Martinez & Craighead, Reference Martinez and Craighead2015; Le Grange, Reference Le Grange2016; Schmidt et al. Reference Schmidt, Adan, Böhm, Campbell, Dingemans, Ehrlich, Elzakkers, Favaro, Giel, Harrison, Himmerich, Hoek, Herpertz-Dahlmann, Kas, Seitz, Smeets, Sternheim, Tenconi, van Elburg, van Furth and Zipfel2016a).

The aims of this review are as follows: Firstly, we summarise the main findings of clinical trials on established AN treatments, that have been reported since a previous review on this topic in this journal (Watson & Bulik, Reference Watson and Bulik2013). We consider treatments as ‘established’ that are widely used in AN treatment, recommended by guidelines and/or have been tested in at least one large randomised controlled trial (RCT), with a minimal sample size of n = 100 (Friedman et al. Reference Friedman, Furberg and DeMets2015). Secondly, we review associated process outcome studies, which shed light on active ingredients of existing treatment approaches. Thirdly, we review emerging treatments for AN, i.e. those that have only been (or are currently being) tested in feasibility or pilot trials so far. Finally, we also attempt to forecast future developments by assessing forthcoming as yet unpublished trials.

Methods

To provide an overview of recent RCTs of established and emerging AN treatments, we conducted a systematic literature search in PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science using a simple search strategy (Royle & Waugh, Reference Royle and Waugh2005), which has high sensitivity (97%) and precision (29%) (McKibbon et al. Reference McKibbon, Wilczynski and Haynes2009). This uses the search terms ‘random*’ (all fields) and ‘anorexia’ (article titles). We limited our search to articles, published in English or German between Oct 2011 (as the review by Watson & Bulik, Reference Watson and Bulik2013 covered the literature up until then) and 31/12/2016. We excluded trials where the main focus of the study was on illness complications, such as osteoporosis, or other non-ED outcomes. Secondary analyses of trials published before Oct 2011 were also not considered. For established treatments, the methodological quality of included trials was assessed according to the Cochrane handbook (Higgins & Green, Reference Higgins and Green2014) and the National Institute of Health criteria for quality assessment of controlled intervention studies (National Institute of Health, 2014). Risk of bias was rated by two independent researchers (US and TB) by using the following criteria: RCT design, sample size n > 30 in each condition, a priori power analysis, lack of recruitment (selection) bias, similarity of groups at baseline, drop-out rate below 20%, intent-to-treat analysis, reporting of all relevant outcomes, validated and reliable outcome measures, adequate method of randomisation, allocation concealment, blinding of assessors, CONSORT statement, registration in clinical trial registry, good adherence to intervention protocols, avoidance of or similar other interventions in the different conditions, representative population, relevant intervention, clinically relevant primary endpoint. Disagreements were resolved by discussion.

To provide an overview of forthcoming and as yet unpublished trials, we searched major national and international clinical trials registries, including the World Health Organization's International Clinical Trials Registry, clinicaltrials.gov, ISRCTN registry, the Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry, ANZCTR, and the German trials registry, DRKS (search term: anorexia).

PART I: Review of established treatments

Trials in adolescents

We identified eight published (n = 833 patients) and six unpublished trials. In published trials treatment completion rates vary from 64% to 90%. In these studies remission/recovery rates range from 17.2% to 50% at last recorded follow-up (6 to 24 months post-randomisation) (see Table 1 for details).

Table 1. RCTs of established treatments in adolescent or predominantly adolescent populations

Within classes of interventions, studies are ordered by sample size, starting with the largest. EDNOS, eating disorder not otherwise specified; EOT, End of treatment. FU, Follow-up; FBT, family-based treatment; FT, family therapy; ED, eating disorders; MR, Morgan–Russell Scale; IQR, Interquartile range; MFT, multi-family group treatment; PFT, parent-focused treatment; SFT, single-family therapy; SyFT, systemic family therapy; TAU, treatment as usual; ECHO, Expert Carers Helping Others; IP, in-patient treatment; DP, day-patient treatment; MS, medical stabilisation; WR, weight restoration; EBW, expected body weight.

Family interventions

Since the previous review (Watson & Bulik, Reference Watson and Bulik2013), three large RCTs have examined variants of family therapy for adolescents with AN. These include multi-family group therapy (Eisler et al. Reference Eisler, Simic, Hodsoll, Asen, Berelowitz, Connan, Ellis, Hugo, Schmidt, Treasure, Yi and Landau2016) and separated (parents only) family therapy (Le Grange et al. Reference Le Grange, Hughes, Court, Yeo, Crosby and Sawyer2016), both of which had advantages over ED-focused family therapy in the short term. A third RCT found no significant differences between ED-focused family therapy and systemic family therapy (which focuses on general family processes) in weight gain and other outcomes (Agras et al. Reference Agras, Lock, Brandt, Bryson, Dodge, Halmi, Jo, Johnson, Kaye, Wilfley and Woodside2014). These findings suggest that non-specific factors, such as mobilisation of the family and provision of a coherent treatment model are likely to play a role in effecting change in family therapy (Jewell et al. Reference Jewell, Blessitt, Stewart, Simic and Eisler2016). Having said that, it seems that giving parents the opportunity to learn from other families (Eisler et al. Reference Eisler, Simic, Hodsoll, Asen, Berelowitz, Connan, Ellis, Hugo, Schmidt, Treasure, Yi and Landau2016) or to discuss their difficulties without their child being present (Le Grange et al. Reference Le Grange, Hughes, Court, Yeo, Crosby and Sawyer2016) is helpful. Building on these findings, a novel adjunct to family therapy (termed Intensive Parental Coaching) has been developed for parents of ‘poor early responders’ to increase parental self-efficacy regarding refeeding. This has shown promise in a small pilot RCT (Lock et al. Reference Lock, Le Grange, Agras, Fitzpatrick, Jo, Accurso, Forsberg, Anderson, Arnow and Stainer2015). Two as yet unpublished trials (Zucker, Reference Zucker2008; Rhind et al. Reference Rhind, Hibbs, Goddard, Schmidt, Micali, Gowers, Beecham, Macdonald, Todd, Tchanturia and Treasure2014) also focus on parental skills training.

Interventions for relapse prevention

One trial found adjunctive post-hospitalisation outpatient family therapy focusing on family dynamics but not symptoms to be superior to treatment-as-usual (TAU) alone in terms of weight gain and other AN symptoms (Godart et al. Reference Godart, Berthoz, Curt, Perdereau, Rein, Wallier, Horreard, Kaganski, Lucet, Atger, Corcos, Fermanian, Falissard, Flament, Eisler and Jeammet2012).

Different treatment settings or intensities

Two recent RCTs have examined different treatment settings or intensities for adolescents with AN. One of these showed that day-patient treatment after brief inpatient admission was not inferior to longer inpatient treatment in terms of body weight at 12-months follow-up and regarding serious adverse events (Herpertz-Dahlmann et al. Reference Herpertz-Dahlmann, Schwarte, Krei, Egberts, Warnke, Wewetzer, Pfeiffer, Fleischhaker, Scherag, Holtkamp, Hagenah, Bühren, Konrad, Schmidt, Schade-Brittinger, Timmesfeld and Dempfle2014). This suggests that day-care is a safe and less costly alternative to longer inpatient treatment for adolescent patients with non-chronic AN. Another RCT yielded similar results, i.e. shorter hospitalisation of adolescents with AN (for medical stabilisation) had similar outcomes to longer hospitalisation (until weight restoration) (Madden et al. Reference Madden, Miskovic-Wheatley, Wallis, Kohn, Lock, Le Grange, Jo, Clarke, Rhodes, Hay and Touyz2015). A trial evaluating a supportive app whilst waiting for treatment is in progress (Huss & Kolar, Reference Huss and Kolar2016).

Nutritional interventions

One small trial in severely underweight adolescents with AN admitted to paediatric in-patient units assessed the impact of two different refeeding regimes (500 v. 1200 kcals/per day) on weight gain and refeeding-related complications (O'Connor et al. Reference O'Connor, Nicholls, Hudson and Singhal2016). The high-energy regime led to greater weight gain, but not higher rates of complications. Two further trials of different feeding (Golden, Reference Golden2015) and weighing regimes (Froreich, Reference Froreich2016) are in progress.

Medication

No medication trials were published during the last 5 years, one study on aripiprazole is in progress (Moya, 2010).

Trials in adults

We identified 11 published trials (n = 1257 patients) and eight unpublished trials since the previous review. In published trials, treatment completion rates vary from 56% to 93.3%. In these studies remission/recovery rates range from 13% to 42.9% at last recorded follow-up (12–24 months post-randomisation) (see Table 2).

Table 2. Trials of established treatments in adults or predominantly adult populations

Within classes of interventions, studies are ordered by sample size, starting with the largest. TAU, treatment as usual; CBT-E, Enhanced Cognitive Behavioural Therapy; FPT, Focal Psychodynamic Therapy; PSR, Psychiatric Status Rating Scale; SSCM, specialist supportive clinical management; MANTRA, Maudsley Model of Anorexia Treatment for Adults; ITT, intention to treat analysis; EoT, end of treatment; FU, Follow-up; EDE, Eating Disorders Examination; ED, eating disorders; BMI, Body Mass Index; ECHO, expert carers helping others.

Individual therapy

Six RCTs have evaluated individual psychotherapies, five of these in out-patients. These include: ED-focused variants of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) (four trials); focal psychodynamic psychotherapy (FPT) where therapeutic foci (e.g. intra-personal conflicts, maladaptive interpersonal patterns and difficulties in psychological functioning) are derived from an in-depth psychodynamic interview (Friederich et al. Reference Friederich, Herzog, Wild, Zipfel and Schauenburg2014) (one trial); the Maudsley Model of Anorexia Nervosa Treatment for Adults (MANTRA; three trials), a novel anorexia-specific psychobiologically informed therapy, centred around a patient manual, which targets cognitive, socio-emotional and interpersonal maintenance factors and meta-beliefs about the utility of AN (Schmidt et al. Reference Schmidt, Wade and Treasure2014); and Specialist Supportive Clinical Management (SSCM; four trials), a pragmatic a theoretical treatment (McIntosh et al. Reference McIntosh, Jordan, Luty, Carter, McKenzie, Bulik and Joyce2006).

The largest of these trials, the ANTOP study, compared (a) an ED specific form of CBT (enhanced CBT; CBT-E) and (b) FPT with (c) an optimised form of TAU (Zipfel et al. Reference Zipfel, Wild, Gross, Friederich, Teufel, Schellberg, Giel, de Zwaan, Dinkel, Herpertz, Burgmer, Lowe, Tagay, von Wietersheim, Zeeck, Schade-Brittinger, Schauenburg and Herzog2014). All three treatments were similarly effective in terms of BMI increase. CBT-E was associated with more rapid weight gain than TAU, and FPT had a more favourable global outcome at follow-up than TAU. FPT was also the most cost-effective option (Egger et al. Reference Egger, Wild, Zipfel, Junne, Konnopka, Schmidt, de Zwaan, Herpertz, Zeeck, Lowe, von Wietersheim, Tagay, Burgmer, Dinkel, Herzog and Konig2016).

Two other trials compared MANTRA with SSCM (Schmidt et al. Reference Schmidt, Oldershaw, Jichi, Sternheim, Startup, McIntosh, Jordan, Tchanturia, Wolff, Rooney, Landau and Treasure2012, Reference Schmidt, Magill, Renwick, Keyes, Kenyon, Dejong, Lose, Broadbent, Loomes, Yasin, Watson, Ghelani, Bonin, Serpell, Richards, Johnson-Sabine, Boughton, Whitehead, Beecham, Treasure and Landau2015, Reference Schmidt, Ryan, Bartholdy, Renwick, Keyes, O'Hara, McClelland, Lose, Kenyon, Dejong, Broadbent, Loomes, Serpell, Richards, Johnson-Sabine, Boughton, Whitehead, Bonin, Beecham, Landau and Treasure2016c), a third compared these treatments with CBT-E (Byrne et al. Reference Byrne, Wade, Hay, Touyz, Fairburn, Treasure, Schmidt, McIntosh, Allen, Fursland and Crosby2017), and a fourth trial compared a different version of CBT with SSCM in patients with severe and enduring AN (SEED-AN) (Touyz et al. Reference Touyz, Le Grange, Lacey, Hay, Smith, Maguire, Bamford, Pike and Crosby2013). Finally, one trial compared two different versions of CBT-E in in-patients with AN (Dalle Grave et al. Reference Dalle Grave, Calugi, Conti, Doll and Fairburn2013).

Overall, none of these specialised psychotherapies were clearly superior to each other or to SSCM. Some advantages over optimised TAU or SSCM have been reported for CBT-E, FPT and MANTRA in terms of the speed of weight gain (Zipfel et al. Reference Zipfel, Wild, Gross, Friederich, Teufel, Schellberg, Giel, de Zwaan, Dinkel, Herpertz, Burgmer, Lowe, Tagay, von Wietersheim, Zeeck, Schade-Brittinger, Schauenburg and Herzog2014), long-term global outcomes (Touyz et al. Reference Touyz, Le Grange, Lacey, Hay, Smith, Maguire, Bamford, Pike and Crosby2013; Zipfel et al. Reference Zipfel, Wild, Gross, Friederich, Teufel, Schellberg, Giel, de Zwaan, Dinkel, Herpertz, Burgmer, Lowe, Tagay, von Wietersheim, Zeeck, Schade-Brittinger, Schauenburg and Herzog2014) and weight gain in patients with a more severe form of the illness (Schmidt et al. Reference Schmidt, Oldershaw, Jichi, Sternheim, Startup, McIntosh, Jordan, Tchanturia, Wolff, Rooney, Landau and Treasure2012, Reference Schmidt, Magill, Renwick, Keyes, Kenyon, Dejong, Lose, Broadbent, Loomes, Yasin, Watson, Ghelani, Bonin, Serpell, Richards, Johnson-Sabine, Boughton, Whitehead, Beecham, Treasure and Landau2015), respectively. However, the overall picture remains that there is no single psychotherapy that is substantially superior to another (Hay, Reference Hay2013; Kass et al. Reference Kass, Kolko and Wilfley2013; Le Grange, Reference Le Grange2016). All mentioned psychological treatments lead to significant improvements in body weight and reductions in AN symptoms, distress levels and clinical impairment. Two further trials of individual therapies are in progress (Cardi et al. Reference Cardi, Ambwani, Crosby, Macdonald, Todd, Park, Moss, Schmidt and Treasure2015; Nevonen, Reference Nevonen2015).

Relapse prevention

One small trial found addition of manual-based e-mail supported guided self-care to show promise compared with TAU alone (Sternheim, Reference Sternheim, Schmidt, Sharpe, Bartholdy, Bonin, Davies, Easter, Goddard, Hibbs, House, Keyes, Knightsmith, Koskina, Magill, McClelland, Micali, Raenker, Renwick, Rhind, Simic, Sternheim, Woerwag-Mehta, Beecham, Campbell, Eisler, Landau, Ringwood, Startup, Tchanturia and Treasure2017). One large trial tested internet-based CBT added to TAU v. TAU alone in the post-hospitalisation phase of treatment (Fichter et al. Reference Fichter, Quadflieg, Nisslmuller, Lindner, Osen, Huber and Wunsch-Leiteritz2012). Whilst there was no difference between groups on the primary outcome (weight gain) in intention-to-treat analysis, CBT-completers showed greater BMI improvement than those receiving TAU only. Two further trials of relapse prevention are in progress, one of them assessing a web-based relapse prevention programme focusing on both patients and carers (Treasure, Reference Treasure2016), the other using a group-based approach (Dalle Grave, Reference Dalle Grave2012).

Carer interventions

Two trials tested interventions for carers and reported outcomes in patients. An exploratory RCT compared family workshops with individual family work and found similar improvements in patients’ body weight and carer's distress in both conditions (Whitney et al. Reference Whitney, Murphy, Landau, Gavan, Todd, Whitaker and Treasure2012). A second large-scale trial compared a brief post-hospitalisation carers skill intervention (delivered by book, DVD and telephone coaching) added to TAU with TAU alone (Hibbs et al. Reference Hibbs, Magill, Goddard, Rhind, Raenker, Macdonald, Todd, Arcelus, Morgan, Beecham, Schmidt, Landau and Treasure2015; Magill et al. Reference Magill, Rhind, Hibbs, Goddard, Macdonald, Arcelus, Morgan, Beecham, Schmidt, Landau and Treasure2016). There were no statistically significant effects of the intervention in terms of the primary outcomes (patient relapse; caregiver distress), although differences were in the anticipated direction. Effects for all secondary outcomes (including bed usage) for both caregiver and patient were small, but all favoured the skills training group. Two further trials are in progress (Bulik, Reference Bulik2012; Schmidt, Reference Schmidt2017).

Medication

A small trial of quetiapine v. placebo found no differences in outcome between groups (Powers et al. Reference Powers, Klabunde and Kaye2012). An as yet unpublished large scale RCT of olanzapine v. placebo in adult outpatients with AN found olanzapine to be superior to placebo in terms of weight gain, but without any effect on illness preoccupations (Attia, Reference Attia2010, Reference Attia2016).

Treatment settings

No trial was published during the period of interest, but one study is in progress (Attia, Reference Attia2010).

Process outcomes

One avenue for improving psychological treatments is to focus on the therapeutic process in order to identify elements that might be particularly important for the success of treatment. A recent systematic review (Brauhardt et al. Reference Brauhardt, de Zwaan and Hilbert2014) summarised the available literature on process-outcome research across all EDs and addressed issues such as treatment settings and modalities, symptom-orientation, motivational enhancement, therapeutic alliance, response patterns, attendance and duration of treatment. Here, we focus instead on within- and between-session processes and patient/therapist views.

Between-session processes

Secondary analyses of the ANTOP study (Zipfel et al. Reference Zipfel, Wild, Gross, Friederich, Teufel, Schellberg, Giel, de Zwaan, Dinkel, Herpertz, Burgmer, Lowe, Tagay, von Wietersheim, Zeeck, Schade-Brittinger, Schauenburg and Herzog2014) showed that less favourable treatment outcomes were associated with patients’ reporting greater negative between-session preoccupation with their therapy/therapist (Hartmann et al. Reference Hartmann, Zeeck, Herzog, Wild, de Zwaan, Herpertz, Burgmer, von Wietersheim, Tagay, Dinkel, Löwe, Resmark, Orlinsky and Zipfel2016). Further research is needed to clarify whether this is a result of less effective therapeutic intervention or of a more complex and severe form of the disorder.

In-session processes

A study applying computerised quantitative text-analysis to verbatim transcripts of therapy sessions from the ANTOP study, found that patients who expressed more negative emotions during mid-treatment had more favourable end-of-treatment and follow-up BMI and ED-symptom outcomes (Friederich et al. Reference Friederich, Brockmeyer, Wild, Resmark, de Zwaan, Dinkel, Herpertz, Burgmer, Löwe, Tagay, Rothermund, Zeeck, Zipfel and Herzog2017). These findings support the idea that increased emotional processing during psychotherapy for AN reduces maladaptive affect regulation mechanisms (e.g. dietary restraint). Importantly, these effects were independent from treatment condition, AN subtype, and illness duration, suggesting that the enhanced expression of negative feelings in psychotherapy constitutes a robust universal action mechanism underlying successful AN treatment.

Patient and therapist views on psychotherapy

Incorporating patients’ views on helpful and less helpful elements of psychotherapy can generate valuable ideas for refining existing treatment approaches. Thematic analyses of patients’ and therapists’ views on MANTRA highlighted strengths of the approach (e.g. clear structure, flexibility and individual tailoring of the treatment) and also yielded testable hypotheses about what might work best for whom, and how this treatment could be improved (Waterman-Collins et al. Reference Waterman-Collins, Renwick, Lose, Kenyon, Serpell, Richards, Boughton, Treasure and Schmidt2014). A complementary analysis of the patients’ views echoed these views (Lose et al. Reference Lose, Davies, Renwick, Kenyon, Treasure, Schmidt and Grp2014). Furthermore, written case formulations of therapists delivering MANTRA were rated for their quality. Regression analyses showed that greater adherence to the treatment model was related to better treatment acceptability and greater therapist reflectiveness/respectfulness to greater reductions in ED symptoms (Allen et al. Reference Allen, O'Hara, Bartholdy, Renwick, Keyes, Lose, Kenyon, Dejong, Broadbent, Loomes, McClelland, Serpell, Richards, Johnson-Sabine, Boughton, Whitehead, Treasure, Wade and Schmidt2016). Other qualitative studies of AN treatment found that patients link a good therapeutic relationship to therapist characteristics, such as acceptance, vitality, challenge and expertise (Gulliksen et al. Reference Gulliksen, Espeset, Nordbo, Skarderud, Geller and Holte2012). In another study, 132 ED patients (not only AN) and 49 ED experts were asked which elements of treatment they consider to be helpful and effective in facilitating recovery (Vanderlinden et al. Reference Vanderlinden, Buis, Pieters and Probst2007). Views among patients were divergent but overlapped with those of therapists. Many different factors were considered important. Patients with restricting type AN considered three elements as more important than other patients: gaining autonomy, reducing social isolation and having family support.

PART II: Review of emerging treatments

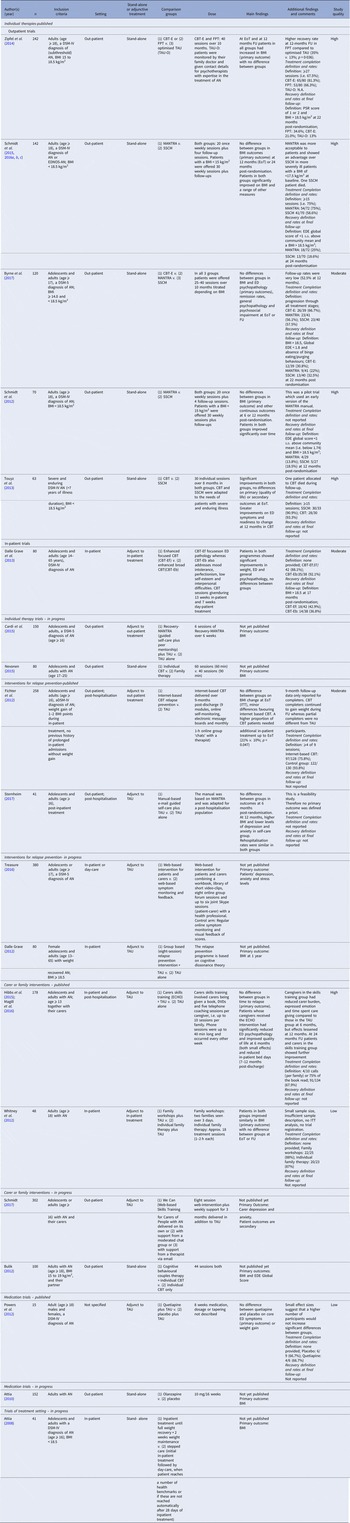

Here, we review novel treatment approaches that have not yet been tested in large-scale RCTs but where there is at least one published feasibility or pilot RCT or where there are proof-of-concept studies and/or cases series and the approach is currently being tested in at least one registered RCT (see Table 3). We identified 11 published and 20 ongoing trials. These can broadly be divided into those that: (a) have been translated from basic research and address specific neurocircuit functions considered to underlie core aspects of AN psychopathology; (b) those that are more broad-based; and (c) a small number of miscellaneous other studies.

Table 3. Emerging treatments

AN, anorexia nervosa; BN, bulimia nervosa; TAU, treatment as usual; CRT, cognitive remediation therapy; ED, eating disorders; EoT, end of treatment; CBT, Cognitive Behavioural Therapy; NNT, non-specific neurocognitive therapy; CREST, Cognitive Remediation and Emotion Skills Training; BMI, Body Mass Index; rTMS, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation; DLPFC, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; EEG, electroencephalography; EDE, Eating Disorder Examination; BED, Binge Eating Disorder; EDI-3, Eating Disorder Inventory-3; ACT, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy; EDNOS, eating disorder not otherwise specified.

Treatments targeting neurocircuit functions

Cognitive remediation therapy (CRT)

Neuropsychological inefficiencies are common in AN, in particular poor cognitive set-shifting (Wu et al. Reference Wu, Brockmeyer, Hartmann, Skunde, Herzog and Friederich2014) and weak central coherence (extreme attention to detail at the expense of the bigger picture) (Lang et al. Reference Lang, Lopez, Stahl, Tchanturia and Treasure2014) [for review see (Lindvall Dahlgren & Rø, Reference Lindvall Dahlgren and Rø2014; Tchanturia et al. Reference Tchanturia, Lounes and Holttum2014; Danner et al. Reference Danner, Dingemans and Steinglass2015)]. CRT aims to improve these basic cognitive functions by using a range of exercises designed to strengthen cognitive flexibility and holistic information processing (e.g. switching between different perspectives or rules in visual illusions or Stroop tasks, increasing levels of abstraction by summary tasks) and meta-cognitive elements (e.g. thinking about one's thinking, reflecting on pros and cons of thinking styles and impact on life). Five small to medium-sized trials have been published. These vary in populations, CRT dose (8 to 30 sessions), comparison treatments (CBT, TAU, exposure treatment, non-specific neurocognitive training) and primary outcomes (set-shifting, ED symptoms, test meal consumption, treatment drop-out).

Two studies found differential short-term improvements in neurocognition for CRT v. comparison treatment (Lock et al. Reference Lock, Agras, Fitzpatrick, Bryson, Jo and Tchanturia2013; Brockmeyer et al. Reference Brockmeyer, Ingenerf, Walther, Wild, Hartmann, Herzog, Bents and Friederich2014). Secondary analyses suggested that CRT in AN may be effective in improving the neural mechanisms underlying poor cognitive flexibility, as it was found to be associated with increased striatal activation during task switching and activation in the dorsolateral prefrontal, sensorimotor and temporal cortex during response inhibition (Brockmeyer et al. Reference Brockmeyer, Walther, Ingenerf, Wild, Hartmann, Weisbrod, Weber, Eckhardt-Henn, Herzog and Friederich2016b). One trial of CRT plus TAU v. TAU alone in in-patients with either AN or bulimia nervosa (Dingemans et al. Reference Dingemans, Danner, Donker, Aardoom, van Meer, Tobias, van Elburg and van Furth2014) found greater improvement in quality of life at end of treatment and greater improvement in ED symptoms at 6 months follow-up. A fourth trial compared CRT to exposure treatment and found less improvement in food intake in a test meal in CRT (Steinglass et al. Reference Steinglass, Albano, Simpson, Wang, Zou, Attia and Walsh2014). A variant of CRT that includes socio-emotional skills training, Cognitive Remediation and Emotion Skills Training (CREST), was compared against TAU in a clinically controlled trial in in-patients, but did not show any benefits in terms of neurocognitive, socio-emotional or ED outcomes (Davies et al. Reference Davies, Fox, Naumann, Treasure, Schmidt and Tchanturia2012).

Taken together, these findings are promising but well-designed large scale studies of CRT are needed to assess the clinical utility of CRT in AN further. Several such trials are in progress (Cook, Reference Cook2012; Ringuenet, Reference Ringuenet2013; Lock, Reference Lock2014; Brockmeyer, Reference Brockmeyer2015; Timko, Reference Timko2016; van Passel et al. Reference van Passel, Danner, Dingemans, van Furth, Sternheim, van Elburg, van Minnen, van den Hout, Hendriks and Cath2016).

Exposure-based therapy

Abnormalities in fear conditioning, possibly partly related to low oestrogen, are thought to be causally implicated in AN (Guarda et al. Reference Guarda, Schreyer, Boersma, Tamashiro and Moran2015). In line with this thinking, exposure therapy to illness-related stimuli (food, body, exercise) may be a promising treatment (Koskina et al. Reference Koskina, Campbell and Schmidt2013). Whilst early studies using food exposure to treat EDs were conducted nearly 40 years ago, in the treatment of AN, food exposure was only recently tested in a small RCT (Steinglass et al. Reference Steinglass, Albano, Simpson, Wang, Zou, Attia and Walsh2014). In this trial exposure therapy lead to increased caloric intake in a test meal and reduced mealtime anxiety compared with CRT. One further RCT of food exposure in adolescents with AN is in progress (Hildebrandt & Sysko, Reference Hildebrandt and Sysko2016).

Preliminary evidence from an un-controlled study and a small RCT further suggests that augmentation with D-cycloserine, an N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor agonist known to facilitate extinction learning, may improve the effects of exposure and response prevention on weight gain in AN (Steinglass et al. Reference Steinglass, Sysko, Schebendach, Broft, Strober and Walsh2007; Levinson et al. Reference Levinson, Rodebaugh, Fewell, Kass, Riley, Stark, McCallum and Lenze2015). Ongoing randomised [see Table 3, (Khalsa, Reference Khalsa2017)] or open-label studies (Guarda, Reference Guarda2016) use the sympathomimetic agent isoproterenol or oestradiol to augment exposure training in AN.

An alternative target for exposure therapy in AN is body-related fear and anxiety, with preliminary studies suggesting that in-vivo body image exposure (Koskina et al. Reference Koskina, Campbell and Schmidt2013) or delivered using novel techniques such as virtual reality (Keizer et al. Reference Keizer, van Elburg, Helms and Dijkerman2016; Gutiérrez-Maldonado et al. Reference Gutiérrez-Maldonado, Ferrer-García, Caqueo-Urízar and Moreno2010; Ferrer-Garcia & Gutierrez-Maldonado, Reference Ferrer-Garcia and Gutierrez-Maldonado2012) lead to short-term improvements in mood, self-esteem and body-image-related symptoms. Clinical trials on body image exposure in patients with AN are lacking, although one ongoing trial is evaluating the use of morphing techniques (Pham-Scottez, Reference Pham-Scottez2011).

Neuromodulation treatments

Improved understanding of the neurocircuitry involved in AN (Lipsman et al. Reference Lipsman, Woodside, Giacobbe and Lozano2013b) has given rise to the use of neuromodulation treatments, such as deep brain stimulation (DBS), repetitive transcranial current stimulation (rTMS), transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) and neurofeedback (Bartholdy et al. Reference Bartholdy, Musiat, Campbell and Schmidt2013; Lipsman et al. Reference Lipsman, Woodside, Giacobbe, Hamani, Carter, Norwood, Sutandar, Staab, Elias, Lyman, Smith and Lozano2013a; McClelland et al. Reference McClelland, Bozhilova, Campbell and Schmidt2013a). Case studies of DBS (targeting the nucleus accumbens, sub-genual cingulate cortex, ventral capsule/ventral striatum or sub-callosal cingulate) to improve AN symptomatology or comorbid symptoms (OCD, depression) have shown promise in highly selected severe and enduring cases. As yet no RCTs have been carried out. Non-invasive methods of brain stimulation (NIBS), i.e. tDCS or rTMS have also shown promise in several case studies (McClelland et al. Reference McClelland, Bozhilova, Nestler, Campbell, Jacob, Johnson-Sabine and Schmidt2013b). Candidate targets for NIBS in EDs, based on an ‘RDoC formulation’ of ED pathology have been described in (Dunlop et al. Reference Dunlop, Woodside and Downar2016). These include potential targets in the cognitive control, positive and negative valences and social processes systems. To date there is only one published proof-of-concept trial (McClelland et al. Reference McClelland, Kekic, Bozhilova, Nestler, Dew, van den Eynde, David, Rubia, Campbell and Schmidt2016) of the use of one session of real or sham high-frequency rTMS applied to the left DLPFC in AN. The study found short term reductions in AN-symptoms and improvements in reward-related decision-making assessed via a delay discounting task. One small trial of EEG alpha neurofeedback, which is supposed to be stress reducing, has also been published with promising results, albeit without any change in the targeted alpha waves (Lackner et al. Reference Lackner, Unterrainer, Skliris, Shaheen, Dunitz-Scheer, Wood, Scheer, Wallner-Liebmann and Neuper2016).

Five further RCTs are in progress, four on therapeutic use of different NIBS and one small trial of DBS (Chastan, Reference Chastan2012; Bartholdy et al. Reference Bartholdy, McClelland, Kekic, O'Daly, Campbell, Werthmann, Rennalls, Rubia, David, Glennon, Kern and Schmidt2015; Gao, Reference Gao2015; Vicari, Reference Vicari2015; Downar & Woodside, Reference Downar and Woodside2016).

Novel medications

A range of different medications has been/is currently being trialled. Dronabinol, a cannabinoid receptor agonist which may promote appetite, has been found to lead to small but significant weight gain above placebo in a pilot RCT in severe and enduring AN (Andries et al. Reference Andries, Frystyk, Flyvbjerg and Stoving2014, Reference Andries, Frystyk, Flyvbjerg and Støving2015).

Oxytocin is a pituitary neuropeptide hormone, synthesised within the hypothalamus. In addition to its key role in parturition, maternal behaviour and pair-bonding, it also plays a role in regulation of broader social interactions, emotional reactivity and feeding behaviour. As such, it is thought that dysregulation of the oxytocinergic system might be involved in the pathophysiology of psychiatric disorders, such as ED, mood, anxiety and autism spectrum disorders (Romano et al. Reference Romano, Tempesta, Di Micioni Bonaventura and Gaetani2015). These authors and others (Maguire et al. Reference Maguire, O'Dell, Touyz and Russell2013) suggest that oxytocin may be a useful adjunct to treatment of AN. One RCT of intranasal oxytocin treatment is in progress (Russell, Reference Russell2016).

Finally, two studies are in progress on fishoils as treatment supplements for AN (Piróg-Balcerzak, Reference Piróg-Balcerzak2012; Bonny, Reference Bonny2013), based on widespread interest in this in other neuropsychiatric disorders (Bos et al. Reference Bos, van Montfort, Oranje, Durston and Smeets2016; Lei et al. Reference Lei, Vacy and Boon2016).

Novel comprehensive treatments and miscellaneous other treatments

Novel comprehensive treatments

A number of so-called ‘third wave’ behavioural therapies (Churchill et al. Reference Churchill, Moore, Furukawa, Caldwell, Davies, Jones, Shinohara, Imai, Lewis and Hunot2013) have been/are being adapted for AN. One shared rationale for the application of these approaches to AN is evidence of widespread socio-emotional processing difficulties in AN (Oldershaw et al. Reference Oldershaw, Hambrook, Stahl, Tchanturia, Treasure and Schmidt2011; Brockmeyer et al. Reference Brockmeyer, Grosse Holtforth, Bents, Herzog and Friederich2013, Reference Brockmeyer, Pellegrino, Munch, Herzog, Dziobek and Friederich2016a; Caglar-Nazali et al. Reference Caglar-Nazali, Corfield, Cardi, Ambwani, Leppanen, Olabintan, Deriziotis, Hadjimichalis, Scognamiglio, Eshkevari, Micali and Treasure2014; Davies et al. Reference Davies, Wolz, Leppanen, Fernandez-Aranda, Schmidt and Tchanturia2016).

Most of these treatments, including an adapted version of Dialectical Behaviour Therapy that focuses on reducing emotional over-control and increasing appropriate socio-emotional signalling (Lynch et al. Reference Lynch, Gray, Hempel, Titley, Chen and O'Mahen2013; Chen et al. Reference Chen, Segal, Weissman, Zeffiro, Gallop, Linehan, Bohus and Lynch2015), interventions using general and eating focused mindfulness interventions (Albers, Reference Albers2011; Marek et al. Reference Marek, Ben-Porath, Federici, Wisniewski and Warren2013; Hartmann et al. Reference Hartmann, Thomas, Greenberg, Rosenfield and Wilhelm2015), and Emotion Acceptance Behaviour Therapy (Wildes & Marcus, Reference Wildes and Marcus2011; Wildes et al. Reference Wildes, Marcus, Cheng, McCabe and Gaskill2014) have only been evaluated in preliminary uncontrolled studies. A related approach is Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), which involves a range of experiential exercises and aims to promote emotional awareness and acceptance as well as adaptive values and goals. ACT has been examined as a potential treatment for AN in one small RCT (Parling et al. Reference Parling, Cernvall, Ramklint, Holmgren and Ghaderi2016). No difference was found between ACT and TAU.

Miscellaneous other treatments

One small trial evaluated acupuncture v. acupressure and massage in AN, with patients in both groups improving equally (Smith et al. Reference Smith, Fogarty, Touyz, Madden, Buckett and Hay2014). Two ongoing trials focus on reducing food-related cognitive biases and AN-related rules and habits (Steinglass, Reference Steinglass2015; Werthmann, Reference Werthmann2015).

Discussion

The findings of this review need to be seen in context. There are big differences in health care systems and consequently in treatment availability/accessibility for people with AN and other EDs between different countries and continents. For example, many countries in continental Europe have a much greater emphasis on in-patient treatment than e.g. the UK and this is reflected in the nature of the research questions asked and trials that are being conducted (e.g. Fichter et al. Reference Fichter, Quadflieg, Nisslmuller, Lindner, Osen, Huber and Wunsch-Leiteritz2012; Godart et al. Reference Godart, Berthoz, Curt, Perdereau, Rein, Wallier, Horreard, Kaganski, Lucet, Atger, Corcos, Fermanian, Falissard, Flament, Eisler and Jeammet2012; Dalle-Grave et al. Reference Dalle Grave, Calugi, Conti, Doll and Fairburn2013; Herpertz-Dahlmann et al. Reference Herpertz-Dahlmann, Schwarte, Krei, Egberts, Warnke, Wewetzer, Pfeiffer, Fleischhaker, Scherag, Holtkamp, Hagenah, Bühren, Konrad, Schmidt, Schade-Brittinger, Timmesfeld and Dempfle2014). Moreover, different psychotherapeutic traditions may affect availability of different treatment modalities, e.g. such as focal psychodynamic therapy (e.g. Zipfel et al. Reference Zipfel, Wild, Gross, Friederich, Teufel, Schellberg, Giel, de Zwaan, Dinkel, Herpertz, Burgmer, Lowe, Tagay, von Wietersheim, Zeeck, Schade-Brittinger, Schauenburg and Herzog2014). This in turn affects whether such treatments are studied or recommended. A case in point is the fact that recent NICE guidance does not include focal psychodynamic therapy as a first line treatment option for AN, even though the evidence base would support this (NICE, 2017).

Established treatments

Huge progress has been made in advancing the evidence-base on treatment of AN, since the previous review by Watson & Bulik (Reference Watson and Bulik2013). This earlier review identified 48 trials (2013 patients), published during a 30-year period (1981–2011). In contrast, the present review identified 19 trials during a 5-year period (2011–2016) including a comparable number of patients (n = 2092), thus more and larger trials have emerged in a much shorter space of time. Of note, the three largest trials published during the last 5 years have been the product of a single research network in one European country, Germany, and four other trials (two large) emanated from a single programme grant in the UK, underscoring the importance of large consortia in the quest for high quality trials.

The focus of recent trials has been mainly on first line psychological interventions. Very little new work has been done in relation to established (antipsychotics or antidepressants) medications, although one large trial of olanzapine v. placebo is in progress (Attia, Reference Attia2010, Reference Attia2016). Available trials paint a nuanced picture of the relative merits of different types of family-based interventions for adolescents with AN. They also support the use of a range of individual psychotherapies for adults, with little information on what works best for whom. The fact that so far no single psychotherapy has emerged as clearly superior to others in the treatment of adults with AN, suggests that common therapeutic factors may play an important role in facilitating change. Future studies should assess the relative contributions of common factors v. specific therapeutic mechanisms in this respect. Of note, there is also a growing number of studies evaluating the impact of involving partners and families of adult patients on these carers and the patients themselves.

Not all studies include a priori definitions of what counts as treatment completion. Where completion rates are reported they range from acceptable to excellent.

Recovery rates vary considerably between studies. In studies of adolescents full recovery rates range from 17.2% to 50% at last recorded follow-up (6–24 months post-randomisation). Recovery rates in adults range from 13% to 42.9% at follow-up (12–24 months post-randomisation). This wide range in recovery rates can be explained by differences between studies in patient mix, length of follow-up and definitions of recovery. Of note, both in studies of adolescents and adults fewer than 50% of patients fully recover during treatment, suggesting that there is considerable room for improvement. As yet, limited data are available on the cost-effectiveness of different first line interventions, with the exception of the ANTOP study, which showed that both focal psychodynamic therapy and CBT-E were more cost-effective than optimised TAU, with focal psychodynamic therapy dominant over CBT-E (Egger et al. Reference Egger, Wild, Zipfel, Junne, Konnopka, Schmidt, de Zwaan, Herpertz, Zeeck, Lowe, von Wietersheim, Tagay, Burgmer, Dinkel, Herzog and Konig2016).

Two studies in children and adolescents examined the impact of treatment setting on AN outcome in more severely ill patients (Herpertz-Dahlmann et al. Reference Herpertz-Dahlmann, Schwarte, Krei, Egberts, Warnke, Wewetzer, Pfeiffer, Fleischhaker, Scherag, Holtkamp, Hagenah, Bühren, Konrad, Schmidt, Schade-Brittinger, Timmesfeld and Dempfle2014; Madden et al. Reference Madden, Miskovic-Wheatley, Wallis, Kohn, Lock, Le Grange, Jo, Clarke, Rhodes, Hay and Touyz2015). Both studies cast doubt on the need for costly prolonged hospital admissions for refeeding, where appropriate alternatives are available, i.e. short admission followed by day-care treatment or out-patient family therapy. In fact, in one of these studies (Herpertz-Dahlmann et al. Reference Herpertz-Dahlmann, Schwarte, Krei, Egberts, Warnke, Wewetzer, Pfeiffer, Fleischhaker, Scherag, Holtkamp, Hagenah, Bühren, Konrad, Schmidt, Schade-Brittinger, Timmesfeld and Dempfle2014), psychosocial outcomes in the group that received day-care were superior to the group that received in-patient treatment, highlighting the potential for iatrogenic effects of prolonged hospitalisation in younger patients.

Whereas earlier trials often combined patients at different developmental (children, adolescents, adults) and illness stages (Watson & Bulik, Reference Watson and Bulik2013), in recent years there has been a clearer separation of trials according to developmental stage (see Tables 1 and 2). In addition, analogous to developments in other mental disorders (McGorry et al. Reference McGorry, Hickie, Yung, Pantelis and Jackson2006; Insel, Reference Insel2007), a stage model for AN has been suggested, ranging from high-risk stage, prodrome and full syndrome through to severe enduring AN (Treasure et al. Reference Treasure, Stein and Maguire2015b), based on available literature on illness course, neurobiological factors, functional decline, and intervention studies. Stage-matched treatment interventions have begun to emerge (Hay & Touyz, Reference Hay and Touyz2015; Brown et al. Reference Brown, McClelland, Boysen, Mountford, Glennon and Schmidt2016), focusing in particular on SEED-AN with one RCT (Touyz et al. Reference Touyz, Le Grange, Lacey, Hay, Smith, Maguire, Bamford, Pike and Crosby2013) specifically adapting psychological therapies for this group (i.e. less emphasis on weight gain, more emphasis on quality of life and adaptive function) (Hay et al. Reference Hay, Touyz and Sud2012; Wonderlich et al. Reference Wonderlich, Mitchell, Crosby, Myers, Kadlec, Lahaise, Swan-Kremeier, Dokken, Lange, Dinkel, Jorgensen and Schander2012). Others have suggested that a range of emerging treatment approaches such as CRT, NIBS or oxytocin may be useful as adjuncts to treatment of SEED-AN (Treasure et al. Reference Treasure, Cardi, Leppanen and Turton2015a). Interventions for early stage illness include family-based interventions for children and adolescents, but early stage illness in adults has so far attracted only limited research attention (Schmidt et al. Reference Schmidt, Adan, Böhm, Campbell, Dingemans, Ehrlich, Elzakkers, Favaro, Giel, Harrison, Himmerich, Hoek, Herpertz-Dahlmann, Kas, Seitz, Smeets, Sternheim, Tenconi, van Elburg, van Furth and Zipfel2016a). Likewise, research on service-level interventions, e.g. exploring the merits of designated early intervention services for ED, is practically non-existent [but see (Brown et al. Reference Brown, McClelland, Boysen, Mountford, Glennon and Schmidt2016)] compared with other areas of mental health research such as psychosis.

Very little is known about sequencing or combinations of interventions if first-line treatments for AN fail and during the period considered no trials considering such questions were conducted. There were however several studies (Fichter et al. Reference Fichter, Quadflieg, Nisslmuller, Lindner, Osen, Huber and Wunsch-Leiteritz2012; Godart et al. Reference Godart, Berthoz, Curt, Perdereau, Rein, Wallier, Horreard, Kaganski, Lucet, Atger, Corcos, Fermanian, Falissard, Flament, Eisler and Jeammet2012; Hibbs et al. Reference Hibbs, Magill, Goddard, Rhind, Raenker, Macdonald, Todd, Arcelus, Morgan, Beecham, Schmidt, Landau and Treasure2015; Sternheim, Reference Sternheim, Schmidt, Sharpe, Bartholdy, Bonin, Davies, Easter, Goddard, Hibbs, House, Keyes, Knightsmith, Koskina, Magill, McClelland, Micali, Raenker, Renwick, Rhind, Simic, Sternheim, Woerwag-Mehta, Beecham, Campbell, Eisler, Landau, Ringwood, Startup, Tchanturia and Treasure2017) that assessed interventions to prevent relapse after discharge from in-patient care, a time when patients are particularly vulnerable to relapse. It is likely that some of the emerging treatments, several of which are currently thought of as adjunctive to other interventions may in future be explored in this context.

Studies exploring within- and between-session processes and patient/therapist views are also appearing, integrated into large-scale studies. These provide valuable pointers on how to improve available treatments. With the availability of novel tools for computational psychotherapy research it is now possible to process much larger amounts of data (Imel et al. Reference Imel, Steyvers and Atkins2015; Owen & Imel, Reference Owen and Imel2016), using text mining and machine learning approaches to investigate the underlying linguistic structures and semantic themes of psychotherapy sessions and to reveal clinically relevant content including emotional, interpersonal and intervention-related topics. This would also allow one to distinguish between different psychotherapy approaches and thus contribute to ensuring treatment fidelity in trials.

Emerging treatments

It has previously been noted that ‘the ED field lags behind other psychiatric disorders in terms of progress in understanding responsible brain circuits and pathophysiology’ (Kaye et al. Reference Kaye, Wagner, Fudge and Paulus2011) and this has hampered the development of new treatments, especially in relation to AN. It is therefore heartening to see that a group of highly targeted treatments, based on neurobiological data/mechanisms are now emerging. These are currently being explored particularly in relation to patients with SEED-AN, as this is the group that has often unsuccessfully undergone multiple conventional treatments at great cost to the individual, their family and society at large. Unsurprisingly therefore, many of these treatments are being used as add-ons to other often fairly intensive treatments, making interpretation of findings more complicated. However, it is conceivable that at least some of these novel brain-directed interventions may be useful for first episode illness, where brain changes are arguably more malleable. Exploration of some emerging treatments as stand-alone interventions may be more feasible in less entrenched illness.

CRT is the novel treatment which is most advanced in terms of current research activity, with five published clinical trials and seven further in progress, and associated research on mechanisms of action and neural correlates. Thus, it is likely that over the next 5 years we will have a much clearer idea as to what the role of this intervention is in the treatment of AN, and what patients and in what setting might benefit most. Additionally, as several forthcoming studies focus on adolescents we may also be clearer about the illness stage at which CRT might be most effective.

In contrast, exposure treatment, although it has been around for several decades, remains the treatment that has as yet not quite emerged. Astonishingly little research has been done/is in progress to specifically and systematically address food and body-related fears in AN. Referring to recent fear extinction literature, which emphasises the violation of expected feared outcomes instead of mere habituation effects as a key mechanism of action of exposure treatment, Murray and colleagues have recently called for a better differentiation between feared cues and feared outcomes in AN (Murray et al. Reference Murray, Loeb and Le Grange2016a, Reference Murray, Treanor, Liao, Loeb, Griffiths and Le Grangeb). Greater clarity in translating extinction theory to the treatment of AN may help facilitate advances in this area. In addition the availability of new morphing and virtual reality technologies may make exposure paradigms more standardised and easier to deliver.

Neuromodulation treatments have huge potential, both as probes of illness mechanisms and as potential interventions in the treatment of AN, but much of this potential is waiting to emerge. Much needs to be learnt about patient selection, intervention parameters, treatment targets and protocols. These technologies continue to evolve, and for example in the case of NIBS are allowing more precise targeting of treatment, use of increasingly briefer and more powerful treatment protocols, probing deeper brain areas and stimulating multiple brain targets simultaneously (Dunlop et al. Reference Dunlop, Woodside and Downar2016). In relation to tDCS, portable devices are now available, which can be used at home, which constitutes another important advance. There is also emerging evidence suggesting that these kinds of interventions may work synergistically when applied with different forms of cognitive training, as yet this combination treatment is completely unexplored in EDs. Finally, another promising neurotechnology is fMRI neurofeedback, which as yet has not been explored in relation to AN (Bartholdy et al. Reference Bartholdy, Musiat, Campbell and Schmidt2013).

In relation to novel medications, the challenges of CNS drug discovery and reinvigorating Big Pharma's interest in psychiatry as a whole, have been noted (Andersen et al. Reference Andersen, Moscicki, Sahakian, Quirion, Krishnan, Race and Phillips2014). Thus, it is perhaps unsurprising that in AN there are only a handful of trials emerging on a diverse range of novel medications.

Several new multi-component treatments are focusing on improving socio-emotional processing in AN. However, many of the more established treatments also explicitly target these processes. Drop-out from some of these newer treatments appears to be quite high (Wildes et al. Reference Wildes, Marcus, Cheng, McCabe and Gaskill2014; Parling et al. Reference Parling, Cernvall, Ramklint, Holmgren and Ghaderi2016). All in all, it remains to be seen, whether these new multi-component treatments have specific advantages over other psychological interventions.

Conclusions

Research funding for EDs remains limited. For example, in the UK, only 0.4% of mental health research expenditure is spent on EDs, compared with 7.2% for depression and 4.9% for psychosis (MQ, 2015). At European level no specific calls for EDs are included in the Horizon 2020 initiative (Schmidt et al. Reference Schmidt, Adan, Böhm, Campbell, Dingemans, Ehrlich, Elzakkers, Favaro, Giel, Harrison, Himmerich, Hoek, Herpertz-Dahlmann, Kas, Seitz, Smeets, Sternheim, Tenconi, van Elburg, van Furth and Zipfel2016a). Against this background the acceleration in knowledge about treatment of AN made in the last 5 years is remarkable.

In addition, a paradigm shift is occurring away from traditional talking therapies towards a range of novel targeted treatments, thus a transformation of the treatment landscape is taking place. Whilst we are still a long way away from delivering personally tailored mechanism-based precision treatments for AN, the development of neurotechnologies for diagnosis, outcome prediction and treatment, gives rise to considerable optimism for the future of people with this devastating illness. It is our view that in order to make further significant advances in treatment of AN utilisation of the full range of these different research approaches and a greater integration and knowledge transfer between neuroscience and clinical research is required. Additionally, greater investment in large-scale programmatic funding at national or international (e.g. European) level is required. Finally, the progress made in research on treatments for AN will only benefit patients if evidence-based treatments are disseminated from controlled settings to clinical care, in a manner that preserves their quality and ensures that underserved populations are reached. Strategies for addressing these research practice gaps have recently been outlined in relation to EDs (Kazdin et al. Reference Kazdin, Fitzsimmons-Craft and Wilfley2017).

Acknowledgements

Ulrike Schmidt is supported by a National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Senior Investigator Award and receives salary support from the NIHR Mental Health Biomedical Research Centre at the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King's College London.

Declaration of Interest

None.