Introduction

Depression is a major public health issue worldwide (Moussavi et al. Reference Moussavi, Chatterji, Verdes, Tandon, Patel and Ustun2007). Projections of the global burden of disease suggest that depression will account for 10% of the total disease burden in high-income countries by 2030 (Mathers & Loncar, Reference Mathers and Loncar2006). The psychosocial vulnerability model of hostility posits that hostile individuals, given their oppositional attitudes and behaviours, are more likely to have increased interpersonal conflicts, lower social support, more stressful life events (SL-E) and higher likelihood of depression (Miller et al. Reference Miller, Smith, Turner, Guijarro and Hallet1996; Kivimäki et al. Reference Kivimäki, Elovainio, Kokko, Pulkkinen, Kortteinen and Tuomikoski2003). Research suggests that SL-E may be independent risk factors (Kendler et al. Reference Kendler, Karkowski and Prescott1999) for depression, with several studies showing SL-E to be associated with an increased risk of both the onset (Caspi et al. Reference Caspi, Sugden, Moffitt, Taylor, Craig, Harrington, McClay, Mill, Martin, Braithwaite and Poulton2003) and recurrence of depression (Bifulco et al. Reference Bifulco, Bernazzani, Moran and Ball2000). Another well-established factor in the aetiology of depression is social support. According to the ‘stress-buffering’ hypothesis (Cohen & Wills, Reference Cohen and Wills1985), social support may protect from the negative effects of stressors such as SL-E, hence protecting against depression. Indeed, a large body of evidence has shown that a low level of social support predicts future depression and recovery from depressive episodes (Brown et al. Reference Brown, Harris, Hepworth and Robinson1994; Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Winett, Meyer, Greenhouse and Miller1999).

We argue that cynical hostility, a personality trait characterized by general cynicism and interpersonal mistrust, may increase the risk of depressive disorders because hostility is related to both SL-E and social support (Smith & Frohm, Reference Smith and Frohm1985; Hardy & Smith, Reference Hardy and Smith1988). However, there is little research on the predictive value of hostility for depressive disorders using large-scale prospective samples. A small-scale cross-sectional study (Felsten, Reference Felsten1996) conducted among undergraduate students found cynical hostility to be strongly associated with depressive mood. Another study (Heponiemi et al. Reference Heponiemi, Elovainio, Kivimäki, Pulkki, Puttonen and Keltikangas-Järvinen2006) examining the longitudinal effects of hostility on depressive tendencies among 1413 men and women found cynical hostility to be related to an increase in depressive tendencies after 5 years. Depressive mood may reinforce hostile feelings and behaviours toward others (Painuly et al. Reference Painuly, Sharan and Mattoo2005), or influence the assessment of cynical hostility (Kendler et al. Reference Kendler, Gatz, Gardner and Pedersen2006); a longer time lag between assessment of hostility and the measurement of depression would allow the examination of whether the influence of cynical hostility on depressive mood persists over time. The aim of the present study is to examine the predictive value of cynical hostility measured in midlife age on depressive mood 19 years later by controlling for baseline common mental disorders, antidepressant medication intake as well as for SL-E and confiding/emotional support at the baseline and during the follow-up.

Method

Data are drawn from the Whitehall II study, established in 1985 as a longitudinal study to examine the socio-economic gradient in health and disease among 10 308 civil servants (6895 men and 3413 women). All civil servants aged 35–55 years in 20 London-based departments were invited to participate by letter, and 73% agreed. Baseline screening (phase 1) took place during 1985–1988, and involved a clinical examination and a self-administered questionnaire. Subsequent phases of data collection have alternated between postal questionnaire alone [phases 2 (1989–1990), 4 (1995–1996), 6 (2001) and 8 (2006)] and postal questionnaire accompanied by a clinical examination [phases 3 (1991–1993), 5 (1997–1999) and 7 (2002–2004)]. The University College London ethics committee approved the study.

Measures

Cynical hostility

Cynical hostility, defined as a personality trait characterized by general cynicism and interpersonal mistrust, was assessed using the Cook–Medley Hostility Scale (Cook & Medley, Reference Cook and Medley1954) at phase 1 (1985–1988). Internal consistency, test–retest reliability and construct validity of this scale have been demonstrated (Smith, Reference Smith1992). Participants completed an abridged 38-item version (Cronbach's α=0.83) of the original 50-item instrument. Item savings were necessary because of the extreme length of the original questionnaire, the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (Hathaway & McKinley, Reference Hathaway and McKinley1943) (numbers of the omitted items are: 19, 183, 237, 253, 386, 394, 410, 455, 458, 485, 504 and 558). Cynical hostility levels were determined based on the quartile distribution [lowest (0–6), middle lowest (7–10), middle highest (11–15) and highest (>16)]. The lowest quartile was the reference category.

We also used the eight-item ‘Cynical Distrust Scale’ (α=0.72), an alternative short-form measure of cynical hostility, derived by factor analysis from the Cook–Medley Hostility Scale by Everson et al. (Reference Everson, Kauhanen, Kaplan, Goldberg, Julkunen, Tuomilehto and Salonen1997). Here again, cynical distrust levels were based on the quartile distribution [lowest (0–8), middle lowest (9), middle highest (10–11) and highest (>11)].

Depressive mood

Depressive mood at follow-up was assessed using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D, Cronbach's α=0.83) at phase 7 (2002–2004). The CES-D, a widely used and validated instrument, is a 20-item self-report questionnaire designed to measure depressive mood in community studies (Radloff, Reference Radloff1977). A score ⩾16 from a total possible score of 60 reflects significant depressive mood and risk for presence of clinical depression (Radloff, Reference Radloff1977).

Covariates

Sociodemographic measures

Sociodemographic measures included age, sex, ethnicity and socio-economic status (SES) assessed by British civil service grade of employment taken from the phase 1 questionnaire.

Health-related behaviours

Health-related behaviours assessed at phase 1 included smoking status (never, ex- and current), exercise (⩾1.5 or <1.5 h of moderate or vigorous exercise per week), heavy alcohol consumption in units of alcohol consumed per week (>22 for men and >15 for women) and body mass index (BMI) (<20, 20–24.9, 25–29.9 or ⩾30 kg/m2).

Common mental disorder

Common mental disorder at baseline was assessed using the self-administered 30-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) at phase 1. In each GHQ item an enquiry is made about the presence or absence of a specific symptom. On the basis of receiver operating characteristics analysis and previous studies, we defined people with a GHQ sum score of 5 or more as cases and those scoring 0–4 as non-cases (Stansfeld & Marmot, Reference Stansfeld and Marmot1992b). In the present study in which GHQ scores were validated against a Clinical Interview Schedule, the sensitivity (73%) and specificity (78%) using this measure of ‘caseness’ was acceptable (Stansfeld & Marmot, Reference Stansfeld and Marmot1992b).

Antidepressant medication

Antidepressant medication at phase 1 was assessed by asking participants whether in the last 14 days they had taken antidepressants prescribed by a doctor (yes/no).

SL-E

SL-E at phases 1, 2 and 5 included the number of SL-E (0, 1, 2 and more) derived from an eight-item self-reported question concerning experiences in the previous 12 months. The instruction ‘The following is a list of things that can happen to people. Try to think back over the past 12 months and remember if any of these things happened to you and, if so, how much you were upset or disturbed by it?’ was followed by a list of events: (1) personal serious illness, injury or operation; (2) death of a close relative; (3) serious illness, injury or operation of a close relative or friend; (4) major financial difficulty; (5) divorce, separation or break-up of personal intimate relationship; (6) other marital or family problem; (7) any mugging, robbery, accident or similar event; (8) change of job or residence.

Confiding/emotional support

Confiding/emotional support at phases 1, 2 and 5 was assessed using the Close Persons Questionnaire (Stansfeld & Marmot, Reference Stansfeld and Marmot1992a) which included a seven-item scale measuring wanting to confide, confiding, sharing interests, boosting self-esteem and reciprocity relative to the first close relationship. Each item of the scale was evaluated using a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 4 with higher scores indicating more confiding/emotional support. The final confiding/emotional support scores were divided in three groups based on tertiles representing different levels of exposure to confiding/emotional support (low, middle, high).

Statistical analysis

Differences in cynical hostility score levels and depressive mood status as a function of the baseline covariates were assessed using a χ2 test.

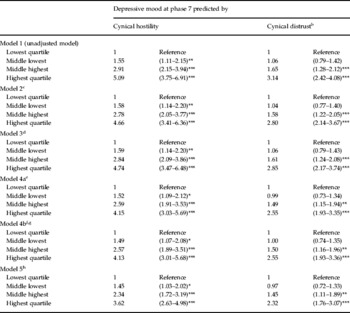

The association between cynical hostility and the depressive mood at follow-up was assessed using logistic regressions in five serially adjusted models. In model 1 no adjustment was made. Model 2 adjusted the likelihood of depressive mood for sex, age, ethnicity and SES. In model 3, the analysis was additionally adjusted for smoking, BMI, alcohol consumption and physical exercise. Model 4 had two elements: model 4a was additionally adjusted for baseline SL-E and confiding/emotional support score (phase 1) and model 4b for SL-E and confiding/emotional support score at baseline and during the follow-up (phases 1, 2 and 5). Model 5 had further adjustments for antidepressant medication and common mental disorders at baseline. The same serial analyses were undertaken to examine the association between cynical distrust and depressive mood at follow-up. The interaction between cynical hostility and sex in relation to depressive mood was not statistically significant (p>0.05), leading us to combine men and women in the analyses.

Results

Only 75% of the 10 308 participants were asked to complete the hostility scale at phase 1 due to this measure being introduced after the start of the baseline survey. A total of 6484 participants responded to the hostility questions (84% of those asked). A total of 6012 participants at phase 7 responded to the CES-D Scale; 3639 of these had data on cynical hostility. Finally, 3399 participants had complete data on cynical hostility, depressive mood and the 13 covariates. The mean age at baseline was 44 (s.d. 5.9) years. The prevalence of depressive mood among these participants at phase 7 was 15.1%.

Table 1 shows the associations between covariates (phase 1), cynical hostility (phase 1) and depressive mood (phase 7). Higher cynical hostility scores were associated with younger age, lower SES, being non-white, higher BMI, antidepressant medication intake, having common mental disorders, higher number of SL-E, lower social network size and higher social isolation (all p⩽0.007). The presence of depressive mood at phase 7 was associated with being female, younger age, lower SES, being non-white, lower alcohol consumption, lower exercise, antidepressant medication, having common mental disorders, higher number of SL-E and lower confiding/emotional support score at baseline (all p<0.001).

Table 1. Bivariate associations of sample characteristics at baseline (phase 1) with cynical hostility score levels (phase 1) and depressive mood (phase 7) (n=3399)

SES, Socio-economic status; BMI, body mass index.

Values are given as number (%).

Table 2 presents the association between cynical hostility at baseline (phase 1) and depressive mood over 19 years later (phase 7). In model 2, adjusting for sex, age, ethnicity and SES, participants in the second quartile of cynical hostility had 1.58 times greater odds [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.14–2.20] of depressive mood compared with those in the first quartile. Those in the third [odds ratio (OR) 2.78, 95% CI 2.03–3.77] and fourth quartile (OR 4.66, 95% CI, 3.41–6.36) also had a greater likelihood of depressive mood when compared with those in the lowest quartile. Further adjustment for health-related behaviours in model 3 (BMI, alcohol consumption and exercise) did not much change these associations. In model 4a, when further adjustment was made for baseline SL-E and confiding/emotional support score, the associations were attenuated, particularly for participants in the highest cynical hostility quartile (16% compared with model 2). In model 4b, when further adjustment was made for SL-E and confiding/emotional support score at the baseline and during the follow-up, a similar percentage of attenuation was observed. Finally, after further adjustment (model 5) for antidepressant medication intake and common mental disorders at baseline, the odds of depressive mood at follow-up were reduced, particularly for participants in the highest cynical hostility level (17% compared with model 3). However, the dose–response association between cynical hostility levels and depressive mood was preserved even in the fully adjusted models. In Table 2 we also present the association between cynical distrust –and depressive mood. As with cynical hostility, we found evidence of a dose–response association between levels of cynical distrust and the likelihood of depressive mood at follow-up.

Table 2. Association of hostility (phase 1) with depressive mood (phase 7)Footnote a

Values are given as odds ratio (95% confidence interval).

a 513 depressive participants; 3399 total participants.

b Cynical distrust is a short-form eight-item subscale of the Cook–Medley Hostility Scale.

c Model 2: adjusted for sex, age, ethnicity, socio-economic position.

d Model 3: model 2+body mass index, alcohol consumption, physical activity.

e Model 4a: model 3+stressful life events, confiding/emotional support at phase 1.

f Role of cumulative stressful life events and confiding/emotional support (phases 1, 2 and 5) in the association between hostility (phase 1) and depressive mood (phase 7).

g Model 4b: model 3+stressful life events and confiding/emotional support at phases 1, 2 and 5.

h Model 5: model 4+antidepressant medication intake+common mental disorder at baseline.

* p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001.

Sensitivity analyses

To test the robustness of the present findings, we examined the predictive value of hostility on depressive mood among participants with no mental health difficulties (common mental disorders or antidepressant medication) at study baseline (phase 1). After excluding participants who reported common mental disorders and antidepressant medication at baseline (phase 1), the number of participants with depressive mood at follow-up decreased by 49% to 260. Nevertheless, the magnitude of the association between cynical hostility and depressive mood at follow-up was similar to that observed in the full sample. Participants in the second quartile of cynical hostility had 1.41 times greater odds (95% CI 0.93–2.12) of depressive mood compared with those in the first quartile. Those in the third (OR 2.30, 95% CI 1.57–3.37) and fourth (OR 3.39, 95% CI 2.27–5.07) quartiles also had greater likelihood of depressive mood, suggesting that cynical hostility is a strong predictor of depressive mood even in individuals free of mental health difficulties at baseline.

Cynical distrust was also assessed at phase 5 of the study; analysis with this measure revealed that it also predicted depressive mood at follow-up, despite the shortened follow-up time (9 years instead of 19 years). Participants in the second quartile of cynical distrust at phase 5 had 1.58 greater odds (95% CI 2.21–2.05) of depressive mood compared with those in the first quartile. Those in the third (OR 2.03, 95% CI 1.61–2.56) and fourth (OR 4.06, 95% CI 3.19–5.17) quartiles also had a greater likelihood of depressive mood, suggesting that cynical distrust is a strong and consistent predictor of depressive mood.

Discussion

In this study we sought to examine the longitudinal association between cynical hostility assessed in midlife and depressive mood in early old age. The risk of depressive mood 19 years later increased in a dose–response relationship by level of cynical hostility. This graded association was preserved after controlling for sex, age, ethnicity, SES, health-related behaviours (BMI, alcohol consumption and exercise), common mental disorders, and antidepressant medication at baseline as well as SL-E, confiding/emotional support score at baseline and during the follow-up; all these factors were found to be associated with hostility or depressive mood or with both of them.

Comparison with previous studies

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first longitudinal cohort study to examine the predictive value of cynical hostility on depressive mood over a 19-year period. Both cynical hostility and depressive mood were assessed using standardized tools. We were able to control for a wide range of confounders that have been found to be important both for hostility and depressive mood. We were also able to control for common mental disorder at baseline. Previous studies have shown cross-sectional (Felsten, Reference Felsten1996) and prospective associations over a 5-year follow-up (Heponiemi et al. Reference Heponiemi, Elovainio, Kivimäki, Pulkki, Puttonen and Keltikangas-Järvinen2006) between neurotic or cynical hostility and depressive mood. Our findings show the effects of cynical hostility on depressive mood to persist over 19 years. Cynical hostility as a personality trait is assumed to be relatively stable during adulthood. (McCrae & Costa, Reference McCrae and Costa1994). In our sample the short-form eight-item cynical distrust scale showed moderate stability over 10 years (correlation coefficient=0.53). The prospective association over the 19-year follow-up could imply that cynical hostility is relatively stable across the lifecourse and predicts depressive mood over time. It is also possible that the observed association is the product of a mutually reinforcing cycle between hostility and depression. Some evidence for the latter explanation comes from the stronger association of depression with short-form cynical distrust measured at phase 5 compared with phase 1. With either interpretation, our results clearly show cynical hostility to be a risk factor for depressive mood.

Our results also show that the cynical distrust scale, a short-form measure of cynical hostility scale developed by Everson et al. (Reference Everson, Kauhanen, Kaplan, Goldberg, Julkunen, Tuomilehto and Salonen1997), shown to be associated with mortality and myocardial infarction, is also associated with depressive mood in a similar way to the longer version of the questionnaire. Thus, our results provide further validation of this shortened version of the cynical hostility scale, a finding that will be of interest to other researchers in the field.

The psychosocial vulnerability model of hostility (Miller et al. Reference Miller, Smith, Turner, Guijarro and Hallet1996; Kivimäki et al. Reference Kivimäki, Elovainio, Kokko, Pulkkinen, Kortteinen and Tuomikoski2003) suggests that hostile individuals may be at greater risk for depressive mood because they are more likely to have lower social support and experience more SL-E. In the present study we found that participants who scored higher on the cynical hostility scale were more likely to have a higher number of SL-E and a reduced confiding/emotional support score. These factors have also been found to be related to the presence of depressive mood, making them potential mediators of the association between cynical hostility and depressive mood. However, statistical adjustment for baseline number of SL-E and confiding/emotional support score explained at best 16% of the association, providing only partial support for the psychosocial vulnerability model of hostility. Similar attenuation (at best 17%) was observed when the association between cynical hostility and depressive mood was adjusted for previous common mental disorders (depression and anxiety) and history of antidepressant intake. We were able to model potential mediators of the association between cynical hostility and depressive mood, particularly SL-E and confiding/emotional social support as time-dependent variables. However, controlling for the cumulative number of SL-E and exposure to confiding/emotional support did not strengthen their status as mediators between cynical hostility and depressive mood. The percentage of attenuation in the association was 16% at best.

Adjustment for SES attenuated the association between hostility and depressive mood, suggesting that it is a possible confounder. On the other hand, we found no significant interactions between SES and hostility in predicting depressive mood. However, we cannot conclude that social context is of little importance for the development of hostility and ultimately the liability of depressive mood. Although personality is often seen as a relatively stable individual attribute, it is likely that socio-economic circumstances affect personality, both in childhood and adulthood (McCrae & Costa, Reference McCrae and Costa1987). Previous studies have shown (Shaffer, Reference Shaffer1979; Brown et al. Reference Brown, Andrews, Bifulco and Veiel1990 a–Reference Brown, Bifulco, Veiel and Andrewsc; Schwartz et al. Reference Schwartz, Friedman, Tucker, Tomlinson-Keasey, Wingard and Criqui1995; Bifulco et al. Reference Bifulco, Brown, Moran, Ball and Campbell1998) that psychological attributes, personality characteristic and self-esteem, for instance, are partially rooted in environmental conditions in childhood, (learning) experiences and rearing styles and that the development of hostility is, in part, explained by factors such as parental behaviour that is overly strict, critical and demanding of conformity. It is also plausible that adult circumstances, such as work-related stressors, contribute to the development or promotion of personality traits, such as hostility. The parental behaviour pattern described above (i.e. overly strict, critical and demanding of conformity) may be viewed as a reflection of the parents' occupational and other life experiences, which are characterized, for example, by job strain (Kivimäki et al. Reference Kivimäki, Elovainio, Kokko, Pulkkinen, Kortteinen and Tuomikoski2003).

There is evidence that personality characteristics are influenced by genetic factors (Heath et al. Reference Heath, Cloninger and Martin1994). Similarly, genetic factors, such as serotonin transporter and receptor polymorphisms, are implicated in the aetiology of depressive disorders (Caspi et al. Reference Caspi, Sugden, Moffitt, Taylor, Craig, Harrington, McClay, Mill, Martin, Braithwaite and Poulton2003; Hamet & Tremblay, Reference Hamet and Tremblay2005; Jokela et al. Reference Jokela, Keltikangas-Jarvinen, Kivimäki, Puttonen, Elovainio, Rontu and Lehtimaki2007). It is therefore possible that genetic factors also influence or moderate the hostility–depressive mood link.

As research suggests that depression is also common in older adults (Jongenelis et al. Reference Jongenelis, Pot, Eisses, Beekman, Kluiter and Ribbe2004), we examined the effects of age on the strength of the association between cynical hostility and depressive mood. Results (not shown) revealed no significant interaction effects of age on this association, again supporting the finding that cynical hostility is a long-term vulnerability factor for depressive mood, irrespective of the effects of ageing.

Study limitations

In interpreting the present results, it is important to note some limitations. First, our cohort of civil servants included neither blue-collar workers nor individuals who were unemployed or retired; thus it is not representative of the general population, which may limit the generalizability of our findings. Second, we assessed depressive mood instead of clinical depression. However, it has been suggested that significant depressive symptomatology could be a risk for clinical depression (Radloff, Reference Radloff1977). For example, findings from longitudinal data on 9900 adults drawn from four sites in the USA showed depressive mood to be strongly associated with first onset of major depression (Horwath et al. Reference Horwath, Johnson, Klerman and Weissman1992). In that study, it was estimated that more than 50% of cases of first onset of major depression were associated with prior depressive mood (Horwath et al. Reference Horwath, Johnson, Klerman and Weissman1992). Thus, it is possible that cynical hostility is also associated with major depression, although this needs to be confirmed in further studies. Third, only 3639 participants had data on cynical hostility (phase 1) and depressive mood (phase 7). As all analyses were based on complete data, only 3399 (44%) participants were included in the present study. However, this did not compromise the statistical power of our analysis. In addition, compared with participants included in this study, those who did not respond to the CES-D and hostility scales were more likely to be: women (37.3% v. 25.4%, p<0.001), non-white (13.4% v. 6.4%, p<0.001), older (24% v. 19.5% aged ⩾50 years, p<0.001) and from lower SES (27.5% v. 13.8%, p<0.001). However, controlling for age, sex, ethnicity and SES did not alter the graded association between cynical hostility and depressive mood as presented in Table 2. We repeated our analyses modelling the association between hostility and depressive mood stratified by sex, age groups, ethnicity and SES. We found no significant interaction between these variables and hostility in relation to depressive mood, supporting therefore the validity of these findings.

Conclusions and implications

In summary, the present study based on a large occupational cohort suggests that cynical hostility is a strong and robust predictor of depressive mood, even after a 19-year period. These findings emphasize the importance of considering individual-level psychological factors, alongside with social–cultural and biogenetic factors, in understanding the predictors of depressive mood or depression. If the relationship between cynical hostility and clinical depression is confirmed, it might have implications for the management of depression, as understanding the role of hostility in the aetiology of depressive disorders might allow better assignment of a treatment.

Acknowledgements

A.S.-M. is supported by a European Young Investigator (EURYI) award from the European Science Foundation. M.G.M. is supported by a Medical Research Council (MRC) Research Professorship. M.K. is supported by the Academy of Finland (grants no. 117604 and 124322). The Whitehall II study is supported by grants from the MRC, British Heart Foundation, Health and Safety Executive, Department of Health, National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (HL36310) of the US National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute on Aging of the US NIH, Agency for Health Care Policy Research (HS06516) and the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Research Networks on Successful Midlife Development and Socio-economic Status and Health.

Declaration of Interest

None.