Introduction

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is an anxiety disorder that can follow exposure to extreme stressful experiences, e.g. combat, earthquake and violent crime (Hughes & Shin, Reference Hughes and Shin2011). It is characterized by three hallmark symptoms: re-experiencing of the traumatic event, withdrawal or avoidance behavior, and hyperarousal or increased startle responses (Hughes & Shin, Reference Hughes and Shin2011).

Imaging plays an important role in uncovering the brain abnormalities of PTSD. Accumulating evidence from neuroimaging studies (Liberzon & Phan, Reference Liberzon and Phan2003; Bremner, Reference Bremner2007; Hughes & Shin, Reference Hughes and Shin2011) has presented a neurocircuitry model of PTSD that emphasizes the role of the amygdala, as well as its interactions with the medial prefrontal cortex and hippocampus. Within this model of PTSD (Liberzon & Phan, Reference Liberzon and Phan2003; Hughes & Shin, Reference Hughes and Shin2011), the amygdala is hyper-responsive, mediates symptoms of hyperarousal and explains the indelible quality of the emotional memory for the traumatic event; and the prefrontal cortex is hyporesponsive, leading to deficits of fear extinction. In addition, the abnormal hippocampal function may underlie declarative memory impairments and deficits in identifying safe contexts. Some other regions including the insula (Rabinak et al. Reference Rabinak, Angstadt, Welsh, Kenndy, Lyubkin, Martis and Phan2011; Garrett et al. Reference Garrett, Carrion, Kletter, Karchemskiy, Weems and Reiss2012) and areas within the brain default mode network (DMN) (Bluhm et al. Reference Bluhm, Williamson, Osuch, Frewen, Steven, Boksman, Neufeld, Theberge and Lanius2009; Lanius et al. Reference Lanius, Bluhm, Coupland, Hegadoren, Rowe, Theberge, Neufeld, Williamson and Brimson2010; Sripada et al. Reference Sripada, King, Welsh, Garfinkel, Wang, Sripada and Liberzon2012b ) also exhibited functional abnormalities in PTSD in previous neuroimaging studies.

Recently, resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI), which attracts increased attention, has indicated that the pathophysiology of many brain diseases including PTSD may be associated with the changes in spontaneous low-frequency fluctuations measured during the resting state (Yin et al. Reference Yin, Jin, Hu, Duan, Li, Song, Chen, Feng, Jiang, Jin, Wong, Gong and Li2011a , Reference Yin, Li, Jin, Hu, Duan, Eyler, Gong, Song, Jiang, Liao, Zhang and Li b ; Sripada et al. Reference Sripada, King, Garfinkel, Wang, Sripada, Welsh and Liberzon2012a ). These blood oxygenation level-dependent signals are thought to be associated with spontaneous neuronal activity (Fox & Raichle, Reference Fox and Raichle2007). In a recent rs-fMRI study, PTSD patients exhibited abnormal low-frequency fluctuations in many cortices and areas of the limbic system, i.e. the frontal and occipital gyri, lingual gyrus and the insula (Yin et al. Reference Yin, Li, Jin, Hu, Duan, Eyler, Gong, Song, Jiang, Liao, Zhang and Li2011b ). However, many brain regions are functionally related and interconnected (Damoiseaux et al. Reference Damoiseaux, Rombouts, Barkhof, Scheltens, Stam, Smith and Beckmann2006; Mantini et al. Reference Mantini, Perrucci, Del Gratta, Romani and Corbetta2007), and the changes in functional interaction between brain regions in PTSD remain unclear up to now.

In rs-fMRI, the functional connectivity analysis algorithm measures the temporal synchrony or correlation between spatially separate regions (Lowe et al. Reference Lowe, Dzemidzic, Lurito, Mathews and Phillips2000). Studies using this method have reported abnormal functional connectivity in many neuropsychiatric diseases, such as Alzheimer's disease (Greicius et al. Reference Greicius, Srivastava, Reiss and Menon2004) and schizophrenia (Woodward et al. Reference Woodward, Karbasforoushan and Heckers2012), contributing to the understanding of neuropathophysiological mechanisms of these diseases. To our knowledge, there have been very limited previous functional connectivity studies in the resting-state focused on PTSD, and the published findings have been varied and even contradictory (Bluhm et al. Reference Bluhm, Williamson, Osuch, Frewen, Steven, Boksman, Neufeld, Theberge and Lanius2009; Rabinak et al. Reference Rabinak, Angstadt, Welsh, Kenndy, Lyubkin, Martis and Phan2011; Sripada et al. Reference Sripada, King, Garfinkel, Wang, Sripada, Welsh and Liberzon2012a ). One study used the amygdala as the seed region and found reduced correlation between the amygdala and anterior cingulate cortex in PTSD patients, suggesting the disturbed coupling between the amygdala and frontal cortex (Sripada et al. Reference Sripada, King, Garfinkel, Wang, Sripada, Welsh and Liberzon2012a ). However, Rabinak et al. (Reference Rabinak, Angstadt, Welsh, Kenndy, Lyubkin, Martis and Phan2011), also using region of interest (ROI) analysis, failed to detect abnormal connectivity between the amygdala and frontal cortex. Using independent component analysis, Bluhm et al. (Reference Bluhm, Williamson, Osuch, Frewen, Steven, Boksman, Neufeld, Theberge and Lanius2009) found that in PTSD patients the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC)/precuneus within the brain DMN exhibited weaker connectivity with the amygdala and hippocampus. Different methodology, variance in co-morbidities and medication exposure may account for the inconsistencies among these studies. In addition, the seed-based or single network-based methods in previous functional connectivity studies restrain the obtained information to the selected regions of interest and make it difficult to examine the functional connectivity patterns on a whole-brain scale.

In the present study, we performed the rs-fMRI technique on a whole-brain scale to explore the abnormalities of functional connectivity in treatment-naive PTSD patients following an earthquake without co-morbid conditions. We hypothesized that whole-brain functional connectivity would be disrupted in patients with a single diagnosis of PTSD, especially between the frontal cortex and the limbic system (e.g. amygdala).

Method

Subjects

This study was approved by the local medical research ethics committee, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. We performed a large-scale PTSD survey of post-earthquake survivors in Sichuan Province, China, which was hit by an 8.0-magnitude earthquake on 12 May 2008. Investigation was carried out in the two most devastated regions 8 months after the earthquake. In Hanwang town, 3100 survivors were interviewed and screened with the PTSD Checklist (PCL; Blanchard et al. Reference Blanchard, Jones-Alexander, Buckley and Forneris1996). Survivors scoring ⩾35 points were then screened with the clinician-administered PTSD scale (CAPS; Blake et al. Reference Blake, Weathers, Nagy, Kaloupek, Gusman, Charney and Keane1995) to confirm the PTSD diagnosis. In Beichuan County, the other severely affected region, a total of 1100 survivors were also interviewed and screened with the PCL and CAPS. After these procedures, all 415 subjects fulfilling the PTSD diagnosis were scheduled for the following fMRI study. In addition, 109 trauma-exposed non-PTSD subjects with PCL scores below 30 points were selected as a control group in this fMRI study.

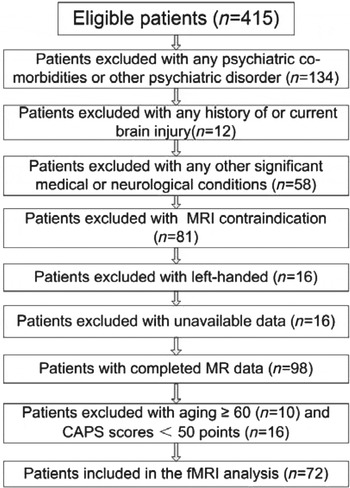

To further confirm the PTSD diagnosis and rule out psychiatric co-morbidities, all subjects were screened with the Chinese version of the structured clinical interview for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (First et al. Reference First, Spitzer, Gibbon and Williams2002) as revised by Professor Lipeng Fei from Beijing Hui Long Guan Hospital, China. The exclusion criteria of the PTSD subjects in this fMRI study included the any psychiatric co-morbidities or other psychiatric disorder (n = 134), any history of or current brain injury (n = 12), as well as any other significant medical or neurological conditions (n = 58), any MRI contraindication (n = 81), left-handed (n = 16), and unavailable data (n = 16). In addition, after the MR scanning, we also excluded the patients aged ⩾60 years (n = 10) and CAPS scores <50 points (n = 16) (Levin et al. Reference Levin, Lazrove and van der Kolk1999; Brady et al. Reference Brady, Pearlstein, Asnis, Baker, Rothbaum, Sikes and Farfel2000). The flowchart of the enrolment population of this study is shown in Fig. 1. So, a total of 72 PTSD patients and 86 trauma-exposed non-PTSD controls with fMRI scanning from 9 to 15 months post-earthquake remained in the fMRI analysis. Finally, the further exclusion criteria for the data analysis also included head translation more than 1.5 mm or rotation than 1.5° during MR scanning.

Fig. 1. Flow chart of the participants enrolled in the study. MRI, Magnetic resonance imaging; CAPS, clinician-administered traumatic stress disorder scale; fMRI, functional MRI.

MRI data acquisition

MRI data were acquired on a 3 Tesla MR scanner (EXCITE; General Electric, USA). All the patients and healthy controls were instructed to close their eyes but be awake during the rs-fMRI examination. A foam pad was used to minimize the head motion of all subjects. Images were then obtained aligned along the anterior commissure–posterior commissure line with a single-shot, gradient-recalled echo planar imaging sequence (repetition time = 2000 ms, echo time = 30 ms, field of view = 220 × 220 mm2, flip angle = 90°, matrix = 64 × 64, slice thickness = 3 mm, slice gap = 1 mm). Each brain volume involved 30 slices. A total of 200 brain volumes were collected, resulting in a total scan time of 400 s.

Data pre-processing

Pre-processing of functional images was carried out using the SPM8 software package (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm). First, slice-timing adjustment and realignment for head-motion correction were performed. A total of 15 PTSD patients and nine non-PTSD controls were excluded from further analysis because of excessive movement (translation exceeded 1.5 mm or rotation exceeded 1.5°). Consequently, 57 PTSD and 77 controls remained. We also evaluated the group differences in translation and rotation of head motion according to the following formula (Liao et al. Reference Liao, Chen, Feng, Mantini, Gentili, Pan, Ding, Duan, Qiu, Lui, Gong and Zhang2010):

$$ \eqalign {{\rm Head\, motion}/{\rm rotation}=\hskip118pt\cr \hskip-20pt{\displaystyle{1 \over {L -1}} \sum\limits_{i = 2}^L {\sqrt {|x_i - x_{i - 1} |^2 + |y_i - y_{i - 1} |^2 + |z_i - z_{i - 1} |^2}} ,$$

$$ \eqalign {{\rm Head\, motion}/{\rm rotation}=\hskip118pt\cr \hskip-20pt{\displaystyle{1 \over {L -1}} \sum\limits_{i = 2}^L {\sqrt {|x_i - x_{i - 1} |^2 + |y_i - y_{i - 1} |^2 + |z_i - z_{i - 1} |^2}} ,$$

where L is the length of the time series (L = 200 in this study), and x i , yi and z i are translations/rotations at the ith time point in the x, y and z directions, respectively. The results showed that the two groups had no significant differences in image quality (two-sample t test, t = 0.235, p = 0.814 for translational motion, and t = 0.287, p = 0.775 for rotational motion).

The functional images were then spatially normalized to standard stereotaxic coordinates of the standard Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) and re-sampled into voxel size of 3 × 3 × 3 mm3, and then smoothed by convolution with an isotropic Gaussian kernel of 8 mm full-width at half-maximum (FWHW) to decrease spatial noise. To further reduce the effects of confounding factors unlikely to be involved in specific regional correlation, we also removed several sources of spurious variance by linear regression, including six head motion parameters obtained by rigid body head motion correction, and average signals from cerebrospinal fluid and white matter. Then, the residual time series were band filtered (0.01–0.08 Hz) using the REST software (http://resting-fmri.sourceforge.net).

Data analysis

The cerebrum was segmented into 90 anatomical ROIs according to the Automated Anatomical Labeling (AAL) template using the WFU PickAtlas Tool version 3.0 (http://fmri.wfubmc.edu/software/PickAtlas) (Maldjian et al. Reference Maldjian, Laurienti, Kraft and Burdette2003). These 90 ROIs were used to define the reference time series and have been applied in previous fMRI studies of other brain diseases (Ding et al. Reference Ding, Chen, Qiu, Liao, Warwick, Duan, Zhang and Gong2011; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Zheng, Zhang, Zhong, Wu, Qi, Li, Wang and Lu2012). To assess functional connectivity of each subject, Pearson correlation coefficients were computed between each pair of 90 regional time series, which resulted in a square n × n (n = 90 in the present study) correlation matrix. The correlation coefficients were then converted to z values using Fisher's r-to-z transformation to standardize the statistical analysis because the correlation coefficient r was not normally distributed.

For each group, these z values were entered into a random-effects one-sample two-tailed t test to determine brain regions showing significant interregional correlations. Then, a random-effects two-sample two-tailed t test in a voxel-wise manner was performed to determine the differences of interregional z values between PTSD patients and non-PTSD controls, with age, gender, education years and head motion importing as covariates. False-positive adjustment was performed for multiple-comparison correction (Fornito et al. Reference Fornito, Yoon, Zalesky, Bullmore and Carter2011; Jao et al. Reference Jao, Vertes, Alexander-Bloch, Tang, Yu, Chen and Bullmore2013). As there were all 4005 possible connections represented in the 90 × 90 correlation matrices in this study, we controlled for the probability of type I error for the number of comparisons between patient and control groups (p value < 1/4005 = 0.000 249). In addition, as the study was an exploratory study, we used a lenient significance level of p < 0.001 (uncorrected). To investigate the association between the CAPS scores and interregional connectivity in PTSD patients, the connectivities that differed significantly between the PTSD and control groups were extracted as connectivities of interest, then the mean z values of these connectivities of patients were correlated against the CAPS scores, using Pearson correlation analysis. Correlation analysis was performed using SPSS 16.0 (SPSS Inc., USA), and the threshold was set at a significance level of p < 0.05 (uncorrected).

Results

Data from 15 PTSD patients and nine trauma-exposed non-PTSD controls were excluded because of excessive head movement. Demographics and clinical data of the remaining 57 PTSD and 77 non-PTSD controls included in the final fMRI comparison are summarized in Table 1. All subjects were right-handed. There were no significant differences in gender, age or education between the PTSD and control groups (all p > 0.05).

Table 1. Demographics and clinical data of PTSD patients and controls

PTSD, Post-traumatic stress disorder; s.d., standard deviation; CAPS, clinician-administered PTSD scale for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition; –, unavailable data.

a The p values for gender distribution and handedness in the two groups were obtained by the χ 2 test.

b The p values for age and education difference between the two groups were obtained by the two-sample t test.

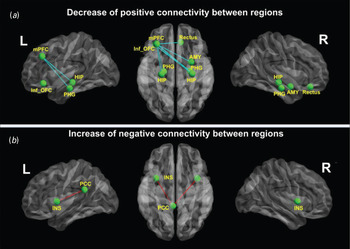

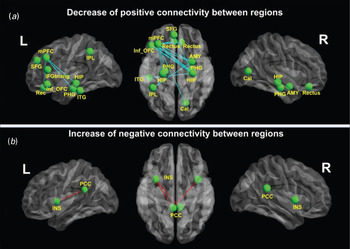

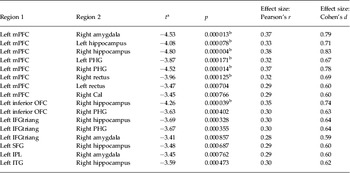

Differences in connectivity between groups

In all, nine connectivities of every two ROIs were significantly different between PTSD patients and non-PTSD controls (Fig. 2), including seven decreased positive connectivities and two increased negative connectivities. Additionally, at a lenient significant level of p < 0.001 (uncorrected), we found 19 abnormal connectivities in PTSD patients, including 16 decreased positive connectivities and three increased negative connectivities (Fig. 3). All of the abnormal connectivities were visualized with the BrainNet Viewer (http://www.nitrc.org/projects/bnv/).

Fig. 2. Differences in the whole-brain functional network between post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and control groups (corrected for multiple comparisons). (a) Compared with non-PTSD controls, PTSD patients showed seven weaker positive connections: between the right amygdala (AMY) and left middle prefrontal cortex (mPFC), between the left mPFC and left/right hippocampus (HIP), between the left mPFC and left/right parahippocampal gyri (PHG), between the left mPFC and right rectus, and between the left inferior orbitofrontal cortex (Inf_OFC) and right hippocampus. (b) In addition, two negative connections were stronger in PTSD patients than in non-PTSD controls: connectivities between the left posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) and left/right insula (INS). L, Left; R, right.

Fig. 3. Differences in the whole-brain functional network between post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and control groups at p < 0.001(uncorrected). (a) Compared with non-PTSD controls, PTSD patients show 16 weaker positive connections: between the left middle prefrontal cortex (mPFC) and right amygdala (AMY), bilateral hippocampal/parahippocampal gyri (PHG), bilateral rectus (Rec) and right Calcarine fissure (Cal), between the left inferior orbitofrontal cortex (Inf_OFC) and right PHG, between the triangular part of the left inferior frontal gyrus (IFGtriang) and the right PHG and right AMY, between the left superior frontal gyrus (SFG) and right hippocampus (HIP), between the left inferior parietal lobe (IPL) and right AMY, and between the left inferior temporal gyrus (ITG) and right HIP. (b) In addition, three negative connectivities are stronger in PTSD patients than in non-PTSD controls: connectivities between the left posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) and left/right insula (INS), and between the right PCC and left INS. L, Left; R, right.

Abnormal positive connectivities

Compared with non-PTSD controls, all seven positive connectivities were weaker in PTSD patients (Fig. 2 a and Table 2). In detail, these were connectivities between the right amygdala and left middle prefrontal cortex (mPFC), between the left mPFC and bilateral hippocampus, between the left mPFC and bilateral parahippocampal gyri, between the left mPFC and right rectus, and between the left inferior orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) and right hippocampus. No increased positive connectivity was found in PTSD patients. In addition, at p < 0.001 (uncorrected), we found 16 weaker positive connectivities, also mainly between the frontal cortex and limbic system. There were also other weaker positive connectivities between the parietal and temporal cortices and the limbic system (for more details of these 16 decreased connectivities, see Fig. 3 a and Table 2).

Table 2. Decrease in positive functional connectivity in PTSD patients compared with controls

PTSD, Post-traumatic stress disorder; mPFC = middle prefrontal cortex; PHG, parahippocampal gyrus; Cal, Calcarine fissure; OFC, orbitofrontal cortex; left IFGtriang, triangular part of the left inferior frontal gyrus; SFG, superior frontal gyrus; IPL, inferior parietal lobe; ITG, inferior temporal gyrus.

a A negative t value represents a decrease.

b Type 1 error corrected by using false-positive adjustment (p < 1/4005 = 0.000 249). All other functional connectivities are present at p < 0.001 (uncorrected).

Abnormal negative connectivities

Only two negative connectivities were stronger in PTSD patients than in non-PTSD controls: between the left PCC and bilateral insula (Fig. 2 b and Table 3). No decreased negative connectivity was exhibited in PTSD patients. At p < 0.001 (uncorrected), the right PCC and left insula also showed increased negative connectivity in PTSD patients (for more details, see Fig. 3 b and Table 3).

Table 3. Increase in negative functional connectivity in PTSD patients compared with controls

PTSD, Post-traumatic stress disorder; PCC, posterior cingulate cortex.

a A positive t value represents an increase.

b Type 1 error corrected by using false-positive adjustment (p < 1/4005 = 0.000 249). All other functional connectivities are present at p < 0.001 (uncorrected).

Validation of the functional connectivity findings

To provide some validation for the whole-brain-based analytical approach used in this study, we performed seed-based functional connectivity analysis (Fox et al. Reference Fox, Snyder, Vincent, Corbetta, Van Essen and Raichle2005; Fox & Greicius, Reference Fox and Greicius2010). We selected four areas as seed regions. These were the left mPFC, the left PCC and the bilateral amygdala. The left mPFC was selected because it showed the most abnormal connections in this study; the left PCC and bilateral amygdala were chosen because they showed abnormal functional connectivities both in our findings and several previous neuroimaging studies (Bluhm et al. Reference Bluhm, Williamson, Osuch, Frewen, Steven, Boksman, Neufeld, Theberge and Lanius2009; Sripada et al. Reference Sripada, King, Garfinkel, Wang, Sripada, Welsh and Liberzon2012a ). The results of comparing each seed's functional connectivity network between PTSD patients and controls also supported our whole-brain functional connectivity findings (see the online Supplementary material).

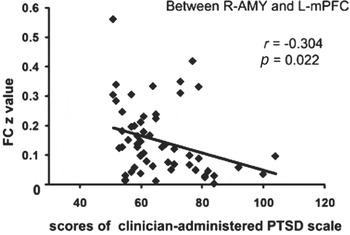

Correlation results

Among all the nine significantly different connectivities, only the connectivity between the right amygdala and the left mPFC negatively correlated with the CAPS scores of patients (Fig. 4). No correlation was found between any other abnormal interregional connectivity and the CAPS performances of patients.

Fig. 4. Correlation results between abnormal connectivities and clinician-administered post-traumatic stress disorder scale (CAPS) scores in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) patients (p < 0.05, uncorrected). Among all the different connectivities, only the connectivity between the right amygdala (R-AMY) and the left middle frontal cortex (L-mPFC) inversely correlated with the CAPS scores of PTSD patients. FC, Functional connectivity.

Discussion

The present rs-fMRI study indicated that PTSD patients following an earthquake suffered from disrupted whole-brain functional connectivity, primarily located between the frontal cortex and limbic system regions. All these findings provide further evidence of cortico-limbic circuitry dysfunction in patients with a single diagnosis of PTSD.

Decreased functional connectivity in PTSD patients

The prefrontal–limbic system plays an important role in learning, memory and affective processing (Braun, Reference Braun2011). Abnormal brain activity in the prefrontal–limbic system in PTSD patients has been previously reported in several fMRI (Garrett et al. Reference Garrett, Carrion, Kletter, Karchemskiy, Weems and Reiss2012; Sripada et al. Reference Sripada, King, Welsh, Garfinkel, Wang, Sripada and Liberzon2012b ) and positron emission tomography/single-photon emission computed tomography (PET/SPECT) studies (Shin et al. Reference Shin, Orr, Carson, Rauch, Macklin, Lasko, Peters, Metzger, Dougherty, Cannistraro, Alpert, Fischman and Pitman2004; Chung et al. Reference Chung, Kim, Chung, Chae, Yang, Sohn and Jeong2006). Weaker functional connectivity between the mPFC and the limbic system observed in the present study is complementary to previous studies and provides important insight into understanding the coupling between the frontal cortex and the limbic system in PTSD patients. Taken together, the abnormal prefrontal–limbic system in these studies may partially explain some defects in PTSD, such as the disturbed emotional processing and memory regulation abilities.

The PFC and amygdala are two key components of the cortico–limbic circuit involved in emotional processing and have wide interconnections with each other (Ghashghaei et al. Reference Ghashghaei, Hilgetag and Barbas2007; Pessoa, Reference Pessoa2008). Decreased PFC activity accompanied by increased amygdala activity in PTSD patients has been reported in many studies with traumatic-related stimuli (Etkin & Wager, Reference Etkin and Wager2007), traumatic-unrelated emotional tasks (Shin et al. Reference Shin, Wright, Cannistraro, Wedig, McMullin, Martis, Macklin, Lasko, Cavanagh, Krangel, Orr, Pitman, Whalen and Rauch2005; Williams et al. Reference Williams, Kemp, Felmingham, Barton, Olivieri, Peduto, Gordon and Bryant2006), and of the resting state (Sripada et al. Reference Sripada, King, Garfinkel, Wang, Sripada, Welsh and Liberzon2012a ). One recent fMRI study used the amygdala as the seed region of functional connectivity and also found decreased connectivity between the amygdala and PFC (Sripada et al. Reference Sripada, King, Garfinkel, Wang, Sripada, Welsh and Liberzon2012a ). The PFC is a region of central importance in the processes of body regulation, fear modulation and working memory (Braun, Reference Braun2011). The amygdala has a critical role in emotion and in fear conditioning (Braun, Reference Braun2011; Sripada et al. Reference Sripada, King, Garfinkel, Wang, Sripada, Welsh and Liberzon2012a ). Decreased mPFC–amygdala connectivity, as reported in the present study, may indicate impaired coupling between them or diminished PFC regulation of the amygdala.

We also found decreased frontal cortex–hippocampus/parahippocampal gyrus connectivity in this study. The hippocampus is essential for memory functions, especially memorizing facts and events, and memory consolidation (Braun, Reference Braun2011). Damage to the hippocampus can cause the inability to form new memories (Braun, Reference Braun2011). The frontal cortex has strong connections to the hippocampus (Tamminga & Buchsbaum, Reference Tamminga and Buchsbaum2004); a connectivity disturbance between them indicates disturbed frontal regulation over the hippocampus which may result in the failure to inhibit negative memory (Tamminga & Buchsbaum, Reference Tamminga and Buchsbaum2004). It should be noted that there are inconsistent findings regarding the hippocampal responsivity in PTSD patients in different task-related neuroimaging studies, both with hypoactivity and hyperactivity (Hughes & Shin, Reference Hughes and Shin2011). It seems that the direction of hippocampal functional abnormalities depends in part on the type of tasks and analysis employed (Bremner, Reference Bremner2007; Hughes & Shin, Reference Hughes and Shin2011). rs-fMRI used here has the advantages of easy application and no impact of task performance difference among subjects (Fox & Greicius, Reference Fox and Greicius2010; Lee et al. Reference Lee, Smyser and Shimony2012), and thus could overcome the limitations of previous studies with task-driven paradigms. One previous rs-fMRI study found decreased functional connectivity within the DMN including the hippocampus and the PFC in PTSD patients (Bluhm et al. Reference Bluhm, Williamson, Osuch, Frewen, Steven, Boksman, Neufeld, Theberge and Lanius2009). That study was based on a hypothesis-driven method to extract one single network (DMN), whereas the present study is based on a data-driven algorithm. Our findings in the whole-brain scale provide another important insight into understanding the abnormal interaction between the hippocampus and PFC in PTSD patients.

Increased functional connectivity in PTSD patients

The PCC is a core component of the brain DMN, mainly involved in memory encoding, consolidation and environmental monitoring (Raichle et al. Reference Raichle, MacLeod, Snyder, Powers, Gusnard and Shulman2001). The insula controls evaluative, experiential and expressive aspects of internal emotional states via visceral and somatic changes evoked during presentations of aversive stimuli (Braun, Reference Braun2011). The increased connectivity between the PCC and insula observed in this study may potentially reflect a tight functional link between visceral perception and memory, and suggests that there might be a threat-sensitive circuitry in PTSD (Sripada et al. Reference Sripada, King, Welsh, Garfinkel, Wang, Sripada and Liberzon2012b ). In a recently published study, Sripada et al. (Reference Sripada, King, Welsh, Garfinkel, Wang, Sripada and Liberzon2012b ) also found increased functional connectivities between the insula and DMN regions. Taken together, these studies provide important insight into understanding the neuropathology of PTSD.

This study has some limitations. First, we used a relatively low sampling rate (repetition time = 2 s); some physiological noise, such as cardiac and respiratory rates, was not collected during the scans. Although the bandpass filtering in the range 0.01–0.08 Hz was used to reduce these physiological noises, the impact of them on functional connectivity remains to be determined. Second, as our study only included subjects who experienced the natural disaster of an earthquake, we urge caution when generalizing these results to other traumatic events. Third, the cross-sectional nature of our measurements did not allow us to ascertain whether the functional connectivity abnormalities in PTSD were present before the traumatic experience or acquired signs that occur after its appearance. Finally, in this study, the male and female subjects in the patient and control groups were not balanced; the gender difference may have potential effects on the vulnerability, tolerance and response to PTSD, which needs to be clarified in further studies.

Conclusions

In summary, the present study examined whole-brain functional connectivity in treatment-naive PTSD patients following an earthquake without co-morbid conditions using rs-fMRI. We found decreased connectivity between the prefrontal cortex and limbic system and increased connectivity between the PCC and insula. Whole-brain functional connectivity may be a non-invasive modality to investigate the neuropathology of PTSD.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S003329171300250X.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (30830046-81171286 and 91232714 to L.L.; 81201077 to Y.Z.), the National 973 Program of China (2009CB918303 to L.L.) and a Chinese Key Grant to G.L. (BWS11J063 and 10z026).

Declaration of Interest

None.