Qualitative political science, the use of textual evidence to reconstruct causal mechanisms across a limited number of cases, is currently undergoing a methodological revolution. Many qualitative scholars—whether they use traditional case-study analysis, analytic narrative, structured focused comparison, counterfactual analysis, process tracing, ethnographic and participant-observation, or other methods—now believe that the richness, rigor, and transparency of qualitative research ought to be fundamentally improved.Footnote 1

The cornerstone of this methodological revolution is enhanced research transparency: the principle that every political scientist should make the essential components of his or her work visible to fellow scholars. Recognition of this principle recently led the American Political Science Association (APSA) to formally recommend higher transparency standards for qualitative (and quantitative) research (APSA 2012). The most broadly applicable tool for enhancing qualitative research transparency is active citation: a technologically enabled citation standard, according to which any citation in a scholarly paper, article, or book chapter that supports a contestable empirical claim is hyperlinked to an excerpt from the original source and an annotation explaining how that excerpt supports the empirical claim, located in a “transparency appendix” attached to the document. Active citation places the essential components of qualitative analysis—evidence, interpretation of evidence, and methodological selection criteria—just one click away from readers. This empowers them to engage more deeply with existing scholarship, not just as passive readers, but as active critics and authors of future research.

This article traces the changes, opportunities, and challenges posed for qualitative political science by the emerging disciplinary best practices of qualitative research transparency, particularly in the form of active citation. The first section defines research transparency in terms of three distinct dimensions and explains why it is a fundamental precondition for other advances in qualitative research. The second section explains precisely what the active citation is and why it is the most generally applicable and logistically convenient means to enhance qualitative research transparency.

WHY IS RESEARCH TRANSPARENCY ESSENTIAL?

Transparency is the cornerstone of social science. Academic discourse rests on the obligation of scholars to reveal to their colleagues the data, theory, and methodology on which their conclusions rest. Unless other scholars can examine evidence, parse the analysis, and understand the processes by which evidence and theories were chosen, why should they trust—and thus expend the time and effort to scrutinize, critique, debate, or extend—existing research?

Three Dimensions of Research Transparency

Research transparency has three dimensions: data, analytic, and production transparency. Recently APSA has officially recognized each of these three dimensions as creating professional obligations of ethical research practice (APSA 2012, 2013).Footnote 2 This section describes the three types of transparency and illustrates why each matters by pointing to weaknesses in current political science research.

Data transparency affords readers access to the evidence or data used to support empirical research claims. This permits readers to appreciate the richness and nuance of what sources actually say, assess precisely how they relate to broader claims, and evaluate whether they have been interpreted or analyzed correctly. Too often in qualitative political science today any effort to examine critical textual evidence ends in frustration. Authors rarely cite sources verbatim and almost never copiously enough to judge whether specific lines were cited in context. Those who would understand, critique, or extend existing work usually find it impractical to track down original sources. Incomplete or page-numberless citations are distressingly common: in a recent graduate seminar, my students found that even in the most highly praised mixed-method work, many sources (often 20% or more) could not be located by any means, including contacting the author. Even when sources can be identified, often the time, trouble, and translation difficulties required to get them impose prohibitive costs. Scouring university libraries, procuring books on inter-library loan, redoing field research to secure specialized publications or unpublished archival material, or reviewing an author's interviews or ethnographic observation notes is often impractical. Generally this means that only a few expert readers, and sometimes no one at all, has any inkling of what another scholar's qualitative data actually look like.

Analytic transparency assures readers access to information about data analysis: the precise interpretive process by which an author infers that evidence supports a specific descriptive, interpretive, or causal claim. Advancing a plausible argument about the precise meaning and reliability of a given piece of evidence requires a nuanced interpretation of it in a particular documentary, historical, strategic, cultural, and social context. Often this requires weighing alternative sources and interpretations and adjudicating ambiguities, tensions, contradictions, and synergies among them. Because this almost inevitably involves uncertain and potentially contestable interpretations, analytical transparency requires that scholars provide an account of the basis on which they reached particular conclusions.

Whereas in the past analytic transparency remained at least theoretically feasible in published qualitative political science, which widely employed classic discursive footnotes, today it is largely precluded. Tighter word limits and the spread of so-called scientific citation forms designed for methodological approaches in which nonqualitative scholars only cite other secondary work, not actual evidence, make it nearly impossible for qualitative scholars to document claims properly.Footnote 3 Even when qualitative evidence is properly cited, it often remains obscure to readers precisely how descriptive, interpretive, and causal inferences were drawn, or what uncertainty attaches to each such analytical claims.Footnote 4 Only in exceptional cases are tensions among conflicting data sources addressed.

Production transparency grants readers access to information about the methods by which particular bodies of cited evidence, arguments, and methods were selected from among the full body of possible choices. Consider first evidence. Social scientific research results always face the concern that the particular observations—the measures, cases and sources—that an author has selected reveal only a subset of the data that could be relevant to the research question. This raises the danger of selection bias, which can occur due to conscious manipulation, unconscious “confirmation bias,” or just plain sloppiness. This is a particular concern in data selection for qualitative case study work, in which scholars generally hand-pick sources, rather than using preassembled aggregate datasets. What, besides their conscience, prevents authors from cherry-picking evidence more likely to support a preferred description, interpretation, or causal theory? Similar concerns arise around the selection of specific theories, hypotheses, and methods: scholars must inevitably select certain frames, interpretations, theories, and methods for intensive attention, while setting others aside. (This conception of production transparency is broader than that in APSA standards, which only cover how data is selected (cf. APSA 2012, 2013).) Production transparency requires that scholars explain to the reader how such choices of evidence, theory, and method were made. At the very least, it gives readers a better awareness of the potential biases that a particular piece of research may contain. At most, the need for scholars to make this explicit will encourage and assist them to conduct less biased research.

Today qualitative political scientists seldom achieve a high degree of production transparency.Footnote 5 Whether research rests on existing secondary sources, published primary material, or archival documents, interviews, ethnographic notes, and other primary evidence assembled by the author, it is almost invariably impossible for anyone except a few experts, often in different fields, to render even a prima facie assessment of how representative that data is. Very little scholarship explicitly mentions, let alone addresses in detail, the selection criteria for evidence. As regards method, qualitative analysts often discuss case selection, yet explicit discussions of specific methodological choices in how to design process tracing, counterfactual analysis, analytic narratives, ethnographic studies, or structured focused comparison are rare. Only with regard to the range of theories considered is there a common research practice (the “literature review”) to provide some modest assurance that a proper range of explanations has been considered.

Data, analytic and process transparency concerns may seem picayune, yet they can be enormously important. Consider the example of Sebastian Rosato's recent book, Europe United: Power Politics and the Making of the European Community (Rosato Reference Rosato2011). Few scholarly works have received more scrutiny: it was published in a major book series, as an article and the subject of a symposium in International Security, and as a guide for current policy makers in Foreign Policy. Yet in all that time no one detected what two scholars who publish regularly in other disciplines quickly spotted: it establishes central theoretical claims by consistently cherry-picking sources and, more troublingly, by explicitly misreading or citing out of context many documents (often easily available secondary sources) to say precisely the opposite of what they unambiguously state. These biases drive the book's results. (Moravcsik Reference Moravcsik2013a; Lieshout Reference Lieshout2012) Without greater transparency in political science, errors such as these are unlikely ever to be detected or debated. The truth is that we have no idea how reliable most existing qualitative political science really is.

Transparency: A Precondition for Improving Qualitative Research

Transparency is an essential foundation for rule-governed and intersubjectively valid social science research, in that it permits scholars to assess research and to speak to one another. It is also a precondition for any other advances in social science method, theory and data collection. As a recent draft APSA report on qualitative methods concludes (APSA 2013):

“Scholarly communities in the social sciences, natural sciences and evidence-based humanities can only exist if their members openly share evidence, results and arguments. Transparency allows those communities to recognize when research has been conducted rigorously, to distinguish between valid and invalid propositions, to better comprehend the subjective social understandings underlying different interpretations, to expand the number of participants in disciplinary conversations, and to achieve scientific progress.”

In other words, any improvements in the quality of research presume transparency. Social scientists may assemble massive datasets and copious citations, deduce clever arguments from sophisticated theories, and use state-of-the-art methods, yet without transparent foundations, these serve no clear purpose, given that neither author nor reader can distinguish more and less compelling interpretations, accurate and inaccurate descriptions, or valid and invalid hypotheses.

Transparency is therefore not simply a precondition for assessing the quality of existing qualitative work, but also for encouraging and rewarding empirical, theoretical and methodological excellence in qualitative research. Without transparency, relatively little incentive exists to acquire new skills, collect better evidence, conduct superior data analysis, or render theory more accurate empirically. Aside from following methodological fashion, what external incentive does an individual scholar in a non-transparent setting have to improve research? Contemporary qualitative case study work in political science, which often lacks transparency, provides a useful illustration. Scholars today, especially graduate students and younger researchers, hesitate to invest in detailed linguistic training, deep area and functional expertise, intensive field work, and rigorous presentation and analysis of qualitative documentation. Scholarly debates and symposiums, journal reviews, and professional assessments of qualitative political science rarely assess its richness or rigor or question the empirical veracity of specific empirical claims (i.e., to what extent textual evidence actually supports theoretical claims). Instead, qualitative debates tend disproportionately to focus on abstract theoretical disagreements. So-called multi-method dissertations tend to invest years in careful and transparent formal models and statistical analysis, then in the final months quickly sketch in lower quality case studies.

For similar reasons, recent decades have seen a profusion of innovative but largely ignored methodological advice on how to better use sophisticated techniques of qualitative causal inference, including conventional narrative, counterfactual analysis, analytic narrative, structured focused comparison, process tracing, and ethnographic and participant observation.Footnote 6 Such techniques are surprisingly rarely used in empirical work, let alone in a sophisticated or innovative manner. One reason is that, without transparent evidence and data analysis, it is difficult to demonstrate to readers that empirical results are thereby more conclusive. The old adage that “one can prove anything with a case study” continues to be a self-fulfilling prophecy, even when methodologists have now conclusively shown it need not be so.

ACTIVE CITATION: THE CORE INSTRUMENT OF QUALITATIVE RESEARCH TRANSPARENCY

The revitalization of qualitative methods in recent years has focused on various tools for promoting research transparency. These include data archiving, qualitative data-basing, hyperlinks, traditional citation, and active citation. All are indispensable instruments for particular purposes. Data archiving is useful for preserving modest-sized collections of field data, such as interviews, ethnographic notes, and informal documents, although it suffers from major logistical, intellectual property, and human subject limitations.Footnote 7 Databases (using programs such as Access, Filemaker, or Atlas) can be extremely useful to manage qualitative data, particularly to support specific research designs where a moderate amount of evidence is analyzed to estimate and manipulate relatively few predefined variables across several cases, using intensive coding and mixed-method data analysis (Lieberman Reference Lieberman2010). Yet they are relatively inflexible and have high up-front costs. Hyperlink citations to online sources, on the model of modern journalism and disciplines such as law and medicine, works for certain narrow applications of on-line research. Yet it fails to accommodate the majority of political science sources that are not found online or accessible under intellectual property law and human subject restrictions, as well as running up against the problem that links are surprisingly unstable over time. Currently, conventional footnotes remain the main instrument to assure research transparency, and they can work for simple cases. Yet as used in political science today, as we have seen, they often fail to provide a high degree of data, analytic or production transparency.

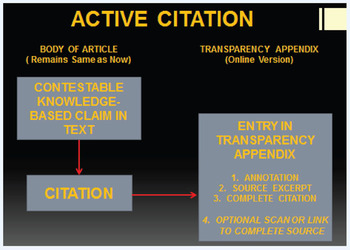

Active citation, by contrast, offers a general standard and format for presenting qualitative results that is far more general, flexible, logistically convenient, and epistemologically appropriate. Active citation envisages that any empirical citation be hyperlinked to an annotated excerpt from the original source, which appears in a “transparency appendix” at the end of the paper, article, or book chapter. The text of the article and the normal citation (footnote, endnote, or in-text citation) remain as they are now. Active citation requires only that the citation be complete and precise—a requirement already almost universally in place today, even if not always adhered to.

The distinctive quality of active citation involves the creation of a transparency appendix attached to the document. Each citation in the main text to a source that supports a contestable empirical claim is hyperlinked to a corresponding entry in the transparency appendix. Each entry contains four elements, three mandatory and one optional:

-

(1) a copy of the full citation

-

(2) an excerpt from the source, presumptively at least 50–100 words

-

(3) an annotation explaining how the source supports the claim being made

-

(4) optionally, an outside link to and/or a scan of the full source.

Figure 1 summarizes this format. While it is designed primarily with traditional textual sources in mind (e.g., primary textual documents, published primary sources, interview or focus group data, oral histories, field notes, diaries and personal records, press clippings, pamphlets, and secondary sources), it is also compatible with photographs, maps, posters, art, audio clips, and other audiovisual material. The transparency index also contains special entries, one at the start and others if needed to support specific citations, which specifically address production transparency: how data, theories, and methods were chosen and by what process the research was done. For journals, the appendix would lie outside of conventional word limits and in most cases, one suspects, would only appear in the online version of the journal. To see an example of an active citation, pertaining to remarks of Thaddeus Stevens in Steven Spielberg's recent film, Lincoln, click on the “activated” citation to this sentence or, if you are reading this in hard copy, go to the link listed in the corresponding reference at the back of the article (Moravcsik Reference Moravcsik2013b).

Figure 1

Active citation enhances data, analytic, and production transparency with relatively modest changes and logistical demands, as compared to current scholarly practices. In most respects it is a conservative reform, involving only proper application of current standards, a modest extension of traditional practices, or the adoption of best practices from other disciplines. The core notion of active citation, namely that qualitative scholars must provide greater access to data and analysis, is already commonplace in fields such as law, public policy, journalism, classical philology, education and history. The use of electronic resources and appendices to achieve transparency is a staple of natural sciences, medicine, and law. The use of these techniques as “best practices” in other fields suggests that its demands are not logistically onerous or unreasonable.

Active citation straightforwardly bolsters data transparency by providing a brief excerpt of the source material, presumptively 50–100 words. If intellectual property, human subject, and logistical considerations permit, a scan or outside link can also take the reader to the full source. Active citation bolsters achieves a high degree of analytic transparency by including an annotation in the appendix entry, in which the author explains how and why the source supports the claim in the main text. This can also be used to elaborate any ambiguity, ambivalence, or uncertainty about that judgment, and to highlight the context (evidentiary, historical, cultural, social, or political) in which it was made. Active citation enhances procedural transparency by providing for entries in the transparency appendix—a specially dedicated one at the beginning and others as needed to support citations—to address issues of procedural transparency: how data, theories, and methods were chosen, and by what process the research was done. All of this is extremely convenient from the perspective of other scholars, because active citation connected all this information to the article, just one click away for the reader.

Active citation involves only a minor increase in workload for editors and authors. Only some citations need to be activated: not background references to literature reviews, theoretical debates or uncontested facts, but only those involving contestable empirical points. In a world in which scholars increasingly collect documents, conduct interviews, copy secondary sources, and keep records electronically, it is far less difficult than it once was to store, access, and input textual data—particularly if one anticipates active citation from the start. The standard remains deliberately flexible, so as not to create an undue burden on qualitative researchers who work under widely varying circumstances. The 50–100 word length of the excerpt, for example, is only a presumptive minimum. The actual length may be shorter or longer, and in extreme cases, with proper cause, may be replaced by a summary or omitted altogether. No one can be expected to cite verbatim text that cannot legally be excerpted, that is inconsistent with human subject or other institutional review board restrictions, or that imposes an undue logistical burden on the scholar. An article based on confidential interviews with Chinese military officers will probably not be as copiously sourced as one on nineteenth-century British documents. An interview that was not taped or transcribed cannot generally be cited verbatim. Such circumstances can be explained in the annotation. At the same time, more fortunate or ambitious scholars are able to reveal more detailed and extensive evidence, since the format retains the possibility for optionally inputting scanned documents or linking to online sources as a supplement to the transcribed excerpt. Over time, different research communities will likely develop distinctive practices and expectations concerning appropriate levels of documentation, reflecting their distinctive constraints.

The length of the annotation is subject to guidelines, but similarly remains ultimately at the discretion of the author. If the link between claim and evidence is obvious, straightforward, or trivial, one sentence should do. If the link is problematic and important, the author can and should explain it in detail. To minimize the logistical difficulties, free add-on software to MSWord (and eventually to LaTeX) is in development, which will automate the creation of the transparency appendix and its entries. Demonstration protocols already exist in current software (Moravcsik Reference Moravcsik2012b).

From the perspective of editors and publishers, active citation can be implemented with only minimal changes to existing paper journal and book publication formats. The main body of a scholarly work, including citation forms, remains unchanged, with the small exceptions of hyperlinks (in online versions) and full citations (already required but not always provided). Even article word limits—which have shrunk over time in a way biased against qualitative scholarship—remain unchanged, with excess content appearing in appendices that resemble existing formats for quantitative or formal appendices, or “supplementary materials” appendices in natural science journals. Active citation can be used in parallel ways with unpublished papers, working papers, online publications, published articles, book chapters, or any other any scholarly form. This means that the transparency appendix could be part of the journal article submission, and would be subject to review—thus eliminating the problem (which often arises with respect to quantitative work) of imperfect ex post enforcement of transparency rules. Journals may decide whether to publish the transparency appendix in the hard-copy version or only in online versions.

Active citation is currently being realized. The National Science Foundation (NSF) is funding a demonstration project, which has commissioned several dozen of the leading scholars in international relations and comparative politics to retrofit classic articles and forthcoming work to the active citation format. They will appear for public viewing on the Qualitative Data Repository at Syracuse University. The team running this program has developed a detailed set of guidelines covering the details of how to construct active citations. NSF funding is also being used to fund computer scientists, who are currently completing software add-ons to popular word-processing programs to automate the creation of a transparency appendix and the entry of individual entries. Conferences and workshops have been held on specific intellectual property, logistics, and human subject concerns, and discussions are being held with major journals and publishers, some of whom are working toward adopting the standard. Several journals are considering adoption.

CONCLUSION

Regardless of their approaches to studying politics, all scholars should embrace the obligation research transparency creates to share with their colleagues critical evidence, interpretive judgments, and procedural decisions. This is an attractive notion not just if one believes political science ought to be “replicable” in the strict sense that any given body of evidence can only be properly interpreted in a single way. No matter what their epistemology, anyone who seeks to generalize about politics should embrace efforts to multiply the variety and subtlety of case study evidence, and to increase the observations from which social scientists can draw descriptive and causal inferences. Those sympathetic to traditional history, interpretivist analysis, constructivist theory or critical social science may have even more reason to welcome enhanced transparency. Such scholars are keenly aware that research conclusions often rest on subtle interpretive judgments drawn from ambiguous evidence about political choices made in specific social, cultural, gendered or institutional circumstances (Geertz Reference Geertz and Geertz1973). Yet most readers of qualitative scholarship today find it difficult to “get inside the heads” of the individuals and groups that other political scientists study. The perceptions, beliefs, interests, cultural frames, identities, deliberative processes, and (often non-rational) strategic choices of those individuals and groups are more often assumed, asserted or implied than actually portrayed empirically. Active citation offers immediate access to the textual record, thereby permitting those real-world individuals and groups to speak directly to readers in their own voices. This can convey a more vivid and immediate sense of politics as it is actually lived, as well as a better understanding of why they act as they do. No one has an interest in anonymous and context-less political science.

Active citation also vindicates a deeper insight of traditional historical and non-positivist epistemologies, namely that comprehending political life is in many ways an essentially interpretive enterprise, one that requires that readers recognize and engage not just the world-views of the human subjects who are being analyzed, but also those of the scholars who conduct the analysis. By revealing these worldviews through enhanced data, analytical and production transparency, active citation can help convey not just a richer and more nuanced impression of political life, but a more accurate understanding of what real actors perceive as being at stake in it, why they make the decisions they do, why scholars who analyze those decisions disagree, and how their colleagues could generate new research insights in the future. For these reasons, qualitative research transparency is a standard that should bring together political scientists of all epistemological and theoretical persuasions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This discussion draws on Moravcsik Reference Moravcsik2010, Reference Moravcsik2012a, Reference Moravcsik2013a, Reference Moravcsikforthcoming. I am grateful to Colin Elman, Tanisha Fazal, Gary Goertz, Alexander Lanowska, Jack Levy, Arthur “Skip” Lupia, James Mahoney, John Owen, and Elizabeth Saunders for comments.