There are many challenges to teaching The Prince well, one of which is helping students resist the temptation to reduce Machiavelli’s ideas to a utilitarian or realist manual devoid of historical context. Responding to the pedagogical problem of students treating the text as a manual for action addressed to them, our approach resituates The Prince in its visual cultural context, thereby specifying Machiavelli’s innovations as a theorist and the importance of plurality and particularity in regard to political action.

Our reading of The Prince integrates the study of selected allegorical images to teach Machiavelli’s moral concepts of prudence, parsimony, liberality, fortune, and impetus.Footnote 1 By discussing emblems, personifications, and paintings, we provide a visual pedagogy for this text. We do not claim direct genealogies or strict parallelisms between presented images and passages. Instead, the purpose of this approach is to acknowledge students’ sometimes literal starting points as readers of The Prince and, through the study of images, to heighten their awareness of complex concepts tied to both familiar and unfamiliar words. Engaging the visual code of Renaissance art allows teachers of political theory to help their students avoid Platonic readings—in the sense of singular and unchanging truths—in favor of an appreciation for Machiavelli’s masterful demonstration of political thought as a manipulation of what were the familiar commonplaces of his time.

Recognizing the codified culture of the Renaissance sharpens our skill set for living in the twenty-first century, which requires the integration of visual and textual hermeneutics, especially concerning politics. In a digital world overflowing with combinations of images and texts, teaching a critical reading of the two combined makes sense beyond the political theory classroom. We provide our students with strategies for bringing the relationship between political message and image into focus by calling attention to how images evoking cultural associations are doing some of the work of political argumentation in The Prince.

In a digital world overflowing with combinations of images and texts, teaching a critical reading of the two combined makes sense beyond the political theory classroom.

My coauthor, Claudia Mesa Higuera, is a literature professor interested in visual culture and a scholar of early modern Spanish literature. When she was working on her own research on Machiavelli, she asked to visit my introductory political theory class on The Prince. Claudia listened to my comments and discussions with students. She had read the text and she heard what was said in the classroom; however, she also was reminded of allegorical images associated with Machiavelli’s concepts. As students worked through their contemporary lexicon and ideological assumptions to understand an early sixteenth-century text, Claudia’s mind conjured images that could help them grasp concepts as opposed to words; she saw what was said. As with her scholarship on emblem studies, she read the images and the text together. The images—familiar to her but unknown to my students and me—shifted her understanding of Machiavelli’s arguments, his indebtedness to context as well as his incendiary innovations. By reworking cultural codes evident in the images representing moral virtues, Machiavelli politicized those concepts by pairing them with particular historical accounts of the actions of leaders. It was a short step from this insight to providing students with images to support their reading of The Prince.

TEACHING WITH IMAGES

An image is a great place to start a political theory discussion. Multiple images representing a particular concept can teach students that several interpretations of a theory are possible. Where can teachers of political theory find images? We present eight images in this article. Databases providing choices and other related materials are available in the online supplemental appendix. To use images in our teaching, we pair them with important passages that describe concepts. We structure our lesson keeping in mind the added time of reading and discussing images.Footnote 2 We can integrate the study of images into our teaching of the text as we proceed or dedicate a special class to working with them.

When I dim the lights, the classroom settles into a thoughtful silence and focuses on the projected images. I ask the students three questions, as follows:

-

• What do you notice or see depicted?

-

• How does a caption change your first impression of an image?

-

• How would you have designed the representation of a particular concept?

After the initial silence, a stream of observations begins. Students are not new to thinking about small images combined with short texts! They already are connoisseurs of memes and other compressed, contextually specific forms of communication. Social media continually exposes them to rematched images and texts. Any reluctance that students display in commenting on the text—that is, remote historical examples and opaque concepts intermingled—stands in contrast to confident comments on images. They take time to notice details in the depictions of personified virtues, observing the figures, their attributes, and objects. They share associations with well-known memes and explain them in terms of their manipulation of meanings, realizing that Machiavelli deploys the familiar images of his time. The students grasp that his writing was situated in relationship to a world of relatively shared meanings that could be affirmed or reworked, not unlike memes in their social media world. Eventually, the visual conversation returns to the textual one. Reflecting on two moments of understanding, before and after the consideration of images, students revise previous understandings of concepts. In what follows, we pair textual passages with images along with a discussion of insights.

PRUDENCE

For students, the word “prudence” carries associations including wisdom, caution, and safety. These are legitimate starting points for reading the text. Although prudence was not granted a separate chapter, the concept permeates the text in Machiavelli’s insistence on the contemplation of past wisdom, alertness for present action, and care for the near future. Understood since the Middle Ages as a cardinal virtue, Prudence as an allegorical personification has its own visual history instructive of the contrast between medieval accounts of virtue and the civic humanism of the Renaissance. An emblem and a painting help “materialize and delimit an otherwise boundless concept” (Ascoli and Capodivacca Reference Ascoli, Capodivacca and Najemy2010, 193).

The first image is from Andrea Alciato’s Emblemata shown in figure 1. An emblem is a symbolic image followed by text. The conventional emblem—emblema triplex—has the following three parts:

-

• a motto (inscriptio)

-

• a symbolic image (pictura)

-

• an epigram or short prose text (subscriptio) that clarifies or expands the connection between the motto and the image (Daly Reference Daly, Preminger and Brogan1993, 326)

Figure 1 Andrea Alciato’s Emblem XVIII: Prudentes (1600)

Source: Public Domain

The Latin inscriptio accompanying emblem XVIII reads Prudentes (The Wise).Footnote 3 The pictura displays Janus, the double-headed Roman god. The subscriptio explains the relationship between the inscriptio and the pictura: because of his dual gaze, Janus is described as cautious or circumspect (Alciato Reference Alciato and Mignault1600, 92). In classical antiquity, he is known as the guardian looking into the past and the future. Directing students’ awareness to the function of the emblem parts shifts the attention from a word to a lesson.

Returning to The Prince, students reconsider Machiavelli’s dedicatory letter to Lorenzo de’ Medici in which he shares his sources of political wisdom: “I have found nothing in my belongings that I care so much for and esteem so greatly as the knowledge of the actions of great men, learned by me from long experience with modern things and a continuous reading of ancient ones” (Machiavelli Reference Machiavelli and Mansfield1985, 3). Caring about concepts and their implications, we encourage students to look beyond keywords. Prudence as a concept need not be named as such; its intelligibility requires understanding the qualities of a mindset, looking back in order to look ahead. Foresight, an important part of prudence, requires looking to the horizon to assess challenges and to respond promptly when action can be effective. The emblem shows Janus looking forward and backward, keeping two different moments in mind. Machiavelli’s text confines this message to a particular audience (i.e., rulers), appropriating the moral commonplace of prudence for a statement on political strategy. A single-minded present orientation endangers the project of political stability: “For men are much more taken by present things than by past ones, and when they find good in the present, they enjoy it and do not seek elsewhere” (Machiavelli Reference Machiavelli and Mansfield1985, 96). Prudence summarizes virtù (i.e., political skill) as a kind of knowing that gives shape to the most effective action.

Moving beyond the word to the concept, a similar meditation on the temporality of strategic political consciousness appears in Titian’s painting, An Allegory of Prudence, which portrays the three ages of man—youth, maturity, and old age—represented by three heads (figure 2). Old age looks to the past, maturity faces us in the present, and youth looks to the future. Depicted below the human heads are three animal heads: a wolf, a lion, and a dog. The animal triptych darkly echoes the faces above it. In the background, a Latin inscription is faintly legible: EX PRAETERITO/PRAESENS PRVDENTER AGIT/NI FVTVRĀ ACTIONĒ DE DETVRPET (“From the past/the present acts prudently/lest it spoil future action”). The painting shows consciousness directed at different moments. The three tenses and their potentially simultaneous urgency highlight the mental demands of effective leadership: a ruler cannot afford only one focus. This is a psychic portrait of an autarch unbounded by a singular way of thinking. The exceptional leader masters single-handedly that which usually takes several to accomplish.

Figure 2 Titian, An Allegory of Prudence (c. 1550–1565)

Source: Public Domain

Titian’s painting asserts the interconnectedness of human and animal natures and can be read in conjunction with Machiavelli’s argument for combining the powers of the lion and the fox, making use of both physical prowess and cunning: “Thus, since a prince is compelled of necessity to know well how to use the beast, he should pick the fox and the lion, because the lion does not defend itself from snares and the fox does not defend itself from wolves. So one needs to be a fox to recognize snares and a lion to frighten the wolves” (Machiavelli Reference Machiavelli and Mansfield1985, 69). Similarly, in chapter XVIII, Machiavelli stresses inner plurality as the necessary condition of leadership. By contrast with the singular identity of the Platonic soul, he symbolically expresses this plurality of the psyche in a hybrid being combining multiple natures. The visual lesson of the painting helps students to understand the concept of prudence as a description of the habits of mind of successful political rulers. Machiavelli has created a political lesson better accessed through the storytelling power of images than through dictionary entries of wisdom, caution, or safety. Prudence is a complex and situationally specific political argument that requires consideration of the moment and its necessity. It is not an invariably right, timeless, moral, or philosophical instruction.

Machiavelli has created a political lesson better accessed through the storytelling power of images than through dictionary entries of wisdom, caution, or safety.

LIBERALITY AND PARSIMONY

Less likely to be used or understood as words, “liberality” and “parsimony” stump students. In chapter XVI, Machiavelli counterintuitively reworks the political merits of these moral virtues—that is, liberality enjoys a good moral reputation but parsimony proves to be the superior political strategy:

Thus, since a prince cannot, without damage to himself, use the virtue of liberality so that it is recognized, he should not, if he is prudent, care about a name for meanness. For with time, he will always be held more and more liberal when it is seen that with his parsimony his income is enough for him, that he can defend himself from whoever makes war on him, and that he can undertake campaigns without burdening the people. (Machiavelli Reference Machiavelli and Mansfield1985, 63)

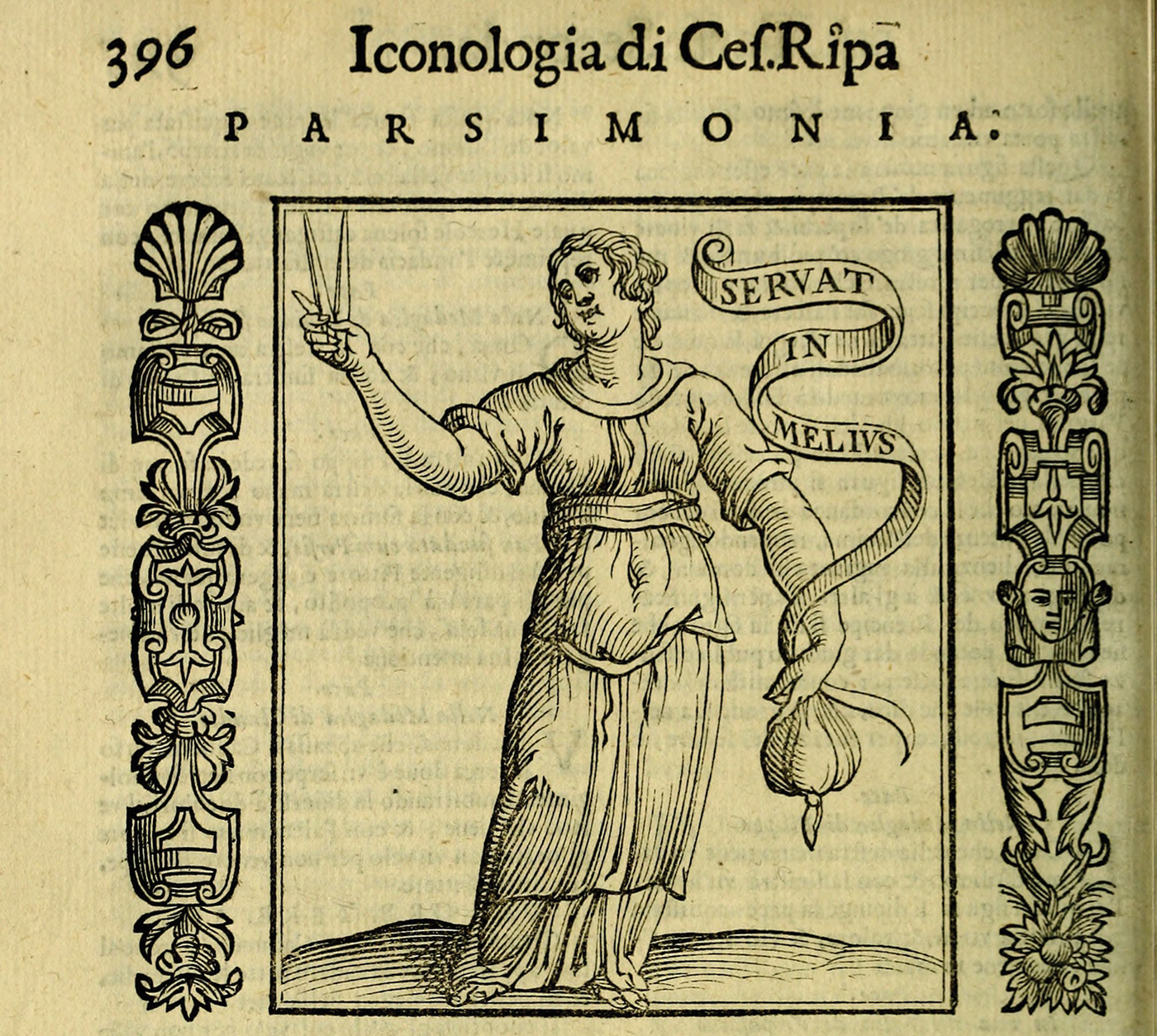

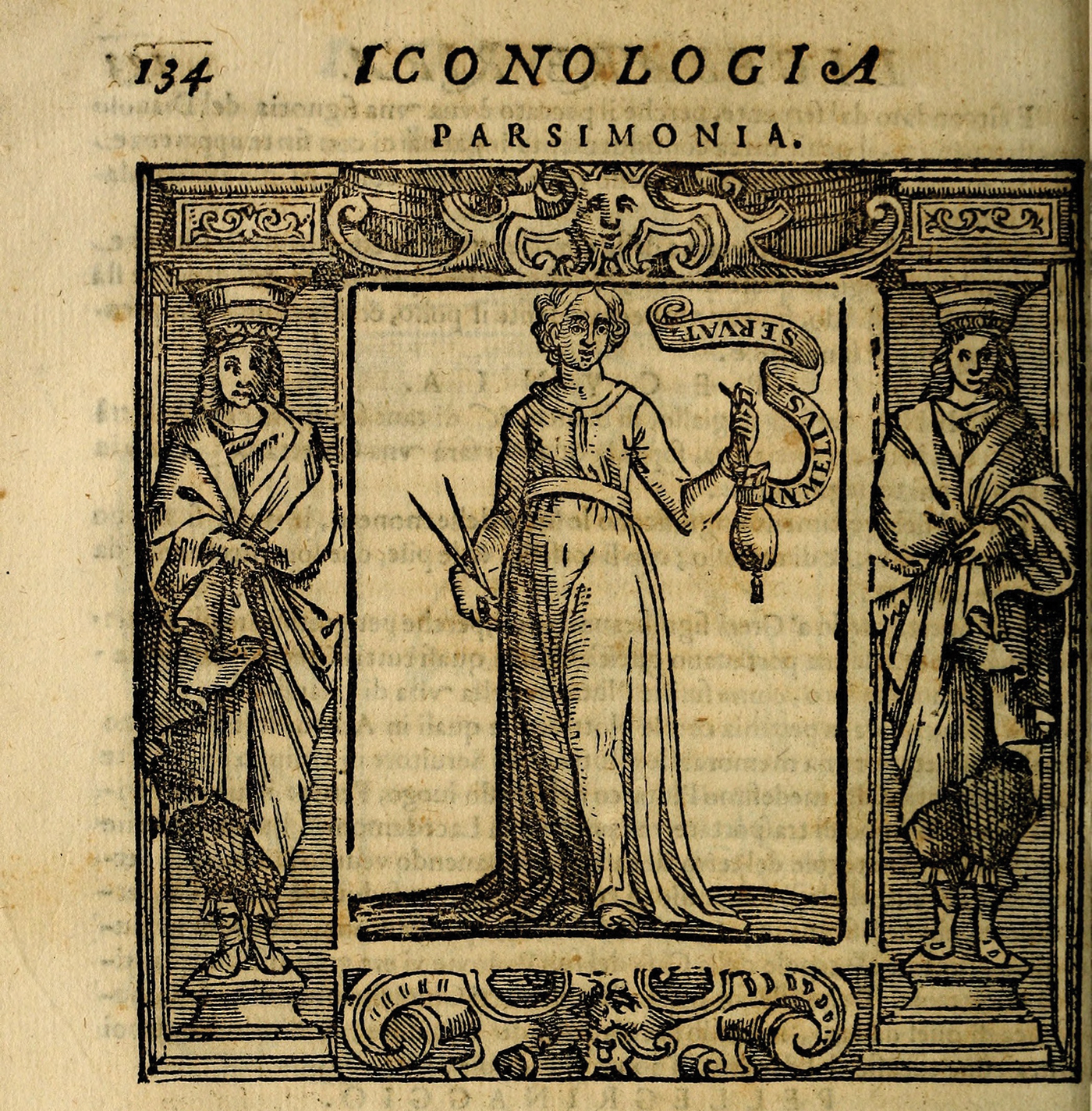

Various editions of Cesare Ripa’s Iconologia provide different illustrations of Parsimony. Whereas the code remains unchanged, visual interpretations of that code are many. A good approach is to ask students to compare and discuss several images for one concept. For example, in the Reference Ripa1618 edition, Parsimony is represented as a mature woman in plain clothes (figure 3). In her right hand, she holds a compass; in her left, a closed bag full of money. A banderole reads: In melius servat (“May the better one serve”). Looking to the right, she indicates her choice: Parsimony will best meet her ends (Ripa Reference Ripa1618, 396). Yet, in the Reference Ripa1613 edition of Iconologia (Ripa Reference Ripa1613), the woman’s gaze is frontal, favoring neither attribute (figure 4). It is undecided. Questions arise: Which is better: to be generous (i.e., the bag of money) or to be economic (i.e., the compass)? What should she choose? A small shift in visual representation—the neutrality of the gaze favoring neither side—yields a more open-ended lesson. The text clarifies the message. Ripa writes that liberality violates measurement: “It is to your advantage to have parsimony because in order to grow your income you need to moderate your expenses” (Ripa Reference Ripa1618, 396). Parsimony enables self-sufficiency and allows one to acquire a politically desirable reputation for liberality. This is a well-known Machiavellian lesson directly indebted to the cultural code.

Figure 3 Cesare Ripa, “Parsimonia,” Iconologia (1618)

Source: Public Domain

Figure 4 Cesare Ripa, “Parsimonia,” Iconologia (1613)

Source: Public Domain

Symbolized by the compass, measurement is the shared attribute of Parsimony and Liberality. In Ripa’s manual, the personification of Liberality shows a woman in white robes, a spread eagle crowning her head (figure 5). She holds two cornucopias. One shows durable riches (including a crown, falling to the floor); the other shows the perishable abundance of nature. As in the representation of Parsimony, the compass appears on the right. This instrument does not leave its circumference: the parsimonious does not exceed the honest and reasonable (Ripa Reference Ripa1618, 396). Not exceeding limits defines both: liberality is not giving with abandon but rather requires prudence, just as parsimony does.

Figure 5 Cesare Ripa, “Liberality,” Iconologia (1618)

Source: Public Domain

This visual lesson informs Machiavelli’s measured recommendations for political action: neither too little nor too much but instead the right amount. Excessive spending compels future taxation or even confiscation of private property, practices that engender hatred. The ingratitude of others and growing expectations over time erode the wealth of the liberal ruler, who must constantly give more to preserve the goodwill of his subjects. It is better to start off measured and to retain the ability to give in the long run. Preserving resources is good for political legitimacy. Although it may seem to be an advantage “to be held liberal,” Machiavelli recommends parsimony as a more reliable path to loyalty and power (Machiavelli Reference Machiavelli and Mansfield1985, 64–65).

When we look at Parsimony and Liberality as allegorical personifications, we see the commonplace meanings in circulation at the time that The Prince was written. Machiavelli’s revaluation of values is in conversation with commonplaces from antiquity as well as well-established iconographic traditions codified in Ripa’s Iconologia—a manual consulted by orators, painters, and poets who want to personify not only virtues and vices but also the arts, sciences, and other abstract concepts. Although the first illustrated edition of Iconologia dates from 1602, the content of Ripa’s manual predates publication of The Prince because it gathers circulating cultural capital from sources from ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome.Footnote 4

FORTUNA AND IMPETUOSITY

In chapter XXV, Machiavelli demands agency through constant adjustment to the imperatives of the moment after acknowledging conventional wisdom on the futility of action:

It is not unknown to me that many have held and hold the opinion that worldly things are so governed by fortune and by God, that men cannot correct them with their prudence, indeed that they have no remedy at all; and on account of this they might judge that one need not sweat much over things but let oneself be governed by chance. […] Nonetheless, in order that our free will not be eliminated, I judge that it might be true that fortune is arbiter of half of our actions, but also that she leaves the other half, or close to it, for us to govern. (Machiavelli Reference Machiavelli and Mansfield1985, 98)

Rulers need to order the world by anticipating the impact of the unexpected in the form of storms, floods, and illnesses. Nature and the actions of others set the pace for politics. While acknowledging fatalism, Machiavelli displaces the divine in favor of fortune and free will.

Alciato’s emblem XCVIII Ars naturam adiuvans (“Art assisting nature”) shown in figure 6 is the first of three images illustrating Machiavelli’s understanding of fortune. The emblem suggests the potential of art (technê) to stabilize nature. The epigram reads: “Art [represented by Hermes] was developed to counteract the effect of Fortune, but when Fortune is bad, it often needs the assistance of Art. Therefore, studious youths learn good arts, which bring with them the benefits of an outcome not subject to chance” (Alciato Reference Alciato1591, 119). In the pictura, Hermes, messenger of the gods, sits on a square pedestal holding the caduceus in one hand. To his left is Fortuna, balancing on a sphere. A billowing sail threatens her equilibrium.

Figure 6 Andrea Alciato’s Emblem XCVIII: Ars naturam adiuvans (1600)

Source: Public Domain

As in the emblem shown in figure 6, Machiavelli invokes the instability of Fortuna to highlight the importance of political agency: the natural world requires an artful approach. Precautions must be taken in advance of natural catastrophes: “And I liken her to one of these violent rivers which, when they become enraged, flood the plains, ruin the trees…it is not as if men, when times are quiet, could not provide for them with dikes and dams so that when they rise later, either they go by a canal or their impetus is neither so wanton nor so damaging” (Machiavelli Reference Machiavelli and Mansfield1985, 98). Fortuna needs skillful taming. This is a theory of moral action applied to the particular needs of politics: one must act in anticipation of problems to protect worldly order.

In the second image (figure 7), an illustration from Charles de Bouelles’s (Reference de Bouelles1510) Liber de Intellectu, blindfolded Fortuna sits on a sphere. Holding her wheel, she balances on an inclined plane that teeters on a fulcrum. She is not well grounded yet she rules the world. Her strength derives from imbalance and unpredictability. Across from Fortuna, Sapientia holds the mirror of self-knowledge. Her wisdom encompasses self and world, signified by the mirror’s margins depicting heavenly bodies. This image dovetails with Machiavelli’s lesson: a ruler cannot divert his attention from worldly matters or afford apolitical self-centeredness. Sapientia rests on a stable square foundation. The legend on Sapientia’s throne reads virtutis, the genitive singular of virtus, which variously means manliness, courage, or resoluteness. A second dialogue is visible: above Fortuna, the fool INSIPIENS proclaims, Te facimus Fortuna deam celoque locamus (“We make you, Fortune, a goddess and elevate you to heaven”). Above Sapientia, the wise man SAPIENS announces, Fidite virtuti: Fortunam fugatior undis (“Trust in virtue: Fortune is more fleeting than waves”).

Figure 7 Charles de Bouelles’s Illustration from the Liber de Intellectu (1510)

Source: University and State Library Duesseldorf, urn:nbn:de:hbz:061:1-18589

These images propose several possible relationships defining fortune as a concept. In Alciato’s emblem, Hermes (art) aids Fortuna (nature). In Bouelles’s illustration, the embedded text makes Sapientia and Fortuna unequal: Fortuna aligns with the fool and Sapientia aligns with the wise man. In both images, Fortuna is a powerful force. The Prince contains no singular advice regarding Fortuna. Prudence and other strategies may aim to appease and guide her, but when there is open conflict with Fortuna the final lesson in the Machiavellian arsenal is impetuosity:

I conclude, thus, that when fortune varies and men remain obstinate in their modes, men are happy while they are in accord, as they come into discord, unhappy…it is better to be impetuous than cautious, because fortune is a woman; and it is necessary, if one wants to hold her down, to beat her and strike her down. And one sees that she lets herself be won more by the impetuous than by those who proceed coldly. And so always like a woman, she is the friend of the young, because they are less cautious, more ferocious, and command her with more audacity. (Machiavelli Reference Machiavelli and Mansfield1985, 101)

In this drama of sexual and combative masculine power, Machiavelli embraces Impetuosity to conquer Fortuna. Consider Ripa’s contrasting critical representation of Impetus:

A young and valiant man of fierce demeanor who should appear barely clothed and in the moment of impetuously confronting an enemy, unsheathing his sword, he will appear as if he were thrusting…blindfolded and with wings on his shoulders accompanied by an equally furious wild boar foaming at the snout, in the same demeanor as the person trying to attack. (Ripa Reference Ripa1613, 390)

Impetus is personified as a potent young man. For Ripa, impetuosity is a dangerous failure, not an aspirational quality. Like a rabid animal, Impetus is a raw force devoid of the prudence present in Machiavelli’s earlier lessons on virtù. Machiavellian impetuosity is virtù unleashed in the moment of crisis. The lack of deliberation is evident in this personification because the youth appears “deprived of the light of the intellect that is the rule and measurement of all human actions” (Ripa Reference Ripa1613, 390). By embracing impetuosity as instrumental, Machiavelli highlights one aspect of the iconographical convention defining fortune. Impetuosity requires agency, not passive acceptance of fate. Although the story reads as one of brutal misogynistic violence, the message of Impetus may be that an effort beyond all imagination and every rule is sometimes necessary for leaders.

The plurality of representations of Fortuna reveals the concept’s complexity. Just as Machiavelli emphasizes the particularities of history, location, and perspective, concepts are not singular or static. They are constituted by relationships; for example, Impetus sheds new light on Fortuna. This also is evident in our third image of Fortuna by the Master of the Boccaccio Illustrations (1470–1490).

The plurality of representations of Fortuna reveals the concept’s complexity.

Found in Giovanni Boccaccio’s De la Ruine des Nobles hommes et femmes (“Of the ruin of noble men and women”), the illustration depicts “The Conflict between Fortuna against Poverty” (figure 8). While Machiavelli’s political framing of Fortuna may be his innovation, the violence and apparent misogyny of the closing paragraph of chapter XXV are not unique to his work. Others have beaten Fortuna. In the illustration, the personification of Poverty (i.e., the ragged woman) beats Fortuna with a stick. With nothing left to lose in this world, Poverty dominates Fortuna. Two competing messages draw on images of Fortuna: (1) action for the powerful (i.e., Machiavelli), and (2) action for the powerless (i.e., Boccaccio). Both highlight the importance of agency. The visual history of Fortuna shows that Machiavelli’s political thought both invokes and reworks a wealth of what would have been familiar stories and images.

Figure 8 Master of the Boccaccio Illustrations, “The Conflict between Fortuna against Poverty,” from Giovanni Boccaccio’s De la Ruine des Nobles hommes et femmes (“Of the ruin of noble men and women”)

Source: Photograph © [1476] Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

CONCLUSION

An image is a generative hermeneutical tool to read a text because it requires that the reader engage in a dialogue between what is being said and what the image has to offer. An image can problematize familiar concepts and open them up to deeper study and critical investigations. Once students can see what Machiavelli and his contemporary audience saw, they have a greater appreciation for his skills as a political thinker, and they are more resistant to reducing The Prince to familiar current ideological assumptions. This approach will not solve the many challenges of reading and teaching The Prince, but it can help us show our students how to be more prudent readers by looking not only at what is immediate and seemingly well known in the present but also to the past and the future when thinking about politics.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Special thanks to Michael Albion Griffin, our ideal reader whose love of history and literature benefitted this project every step of the way.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S104909652000205X.