The undergraduate major in political science has been one of the most popular social science majors on college campuses for many decades. As colleges and universities expanded in the post–World War II period, political science offered vital knowledge in understanding government, politics, and citizenship. Moreover, political science was an excellent training ground for students interested in public-service careers, including law, government, and the nonprofit sector.

Amid rising enrollments for political science, the American Political Science Association (APSA) appointed in 1991 a formal committee, chaired by Professor John Wahlke of the University of Arizona, to study the undergraduate political science major and recommend a model curriculum. The committee’s final report (Wahlke Reference Wahlke1991) officially was titled, “Liberal Learning and the Political Science Major: A Report to the Profession.” Wahlke was a logical candidate to chair this APSA committee because he had taught at several universities and had a long-standing interest in curriculum and pedagogical concerns in the discipline. Indeed, he led an early effort to profile and publicize the syllabi of political science courses. He also was an early president of the Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR) at the University of Michigan and president of APSA in 1977–1978.

The Wahlke Report was intended to serve as a blueprint for political science departments in the development and reform of their undergraduate majors. The Report’s eight principal recommendations suggested that the major should emphasize a common set of core topics; teach students basic political analysis and accompanying analytic skills; and incorporate principles of “ethnic, gender, and cultural diversity” and the “international dimensions” of politics and public policy into the curriculum (Wahlke Reference Wahlke1991). Overall, the Report’s authors recommended a focus on the liberal arts within the major and emphasized the capacity of the major to prepare students to be productive, knowledgeable citizens. Importantly, the Report also called for a sequencing of the major and substantial core courses to be offered; the vision of the major was comprehensive and sequential so that students would build on their coursework as they progressed through the major. On graduation, they would have a broad academic background that would position them to be responsible, engaged citizens and productive employees.

Significantly, the Wahlke Report was an effort to establish norms for an undergraduate major and provide guidance on the substantive content of the major. It was published in APSA’s journal of record, PS: Political Science & Politics, and therefore received wide distribution within the discipline. The actual impact of the Wahlke Report is difficult to assess, in part because the institutional diversity of political science departments leads to significant variation in undergraduate curricula. Furthermore, the Report was only advisory, and APSA does not review or accredit specific departments. Moreover, many departments may have believed that they were already following the basic principles of the Wahlke Report and therefore did not need to undertake any major curricular innovation.

Yet, even before the COVID-19 pandemic, profound social and economic trends were buffeting higher education, with important consequences for the political science undergraduate major. Many universities and colleges are increasingly diverse on the basis of race and ethnicity, especially in rapidly expanding universities and community colleges in the South and Southwest. Many students in these universities also are the first generation of their family to attend college (APSA 2011; Guthrie Reference Guthrie2019). Moreover, universities and colleges currently are enrolling students at many different career and life stages with a significant increase in transfer students, especially from community colleges to public four-year universities (US Department of Education 2019).

The pandemic appears to be accelerating other trends. The shift to online education has been underway for years (US Department of Education 2019), with many universities offering online classes. However, the closure of universities for in-person instruction and the corresponding shift to online instruction likely will intensify this change even after the immediate effects of the pandemic have waned. Many small liberal arts colleges and regional public universities have had noticeable declines in their student enrollment (National Student Clearinghouse 2019). With the escalating cost of higher education and the profound effects of the pandemic, many students increasingly may opt for less-expensive public universities and community colleges. Thus, it is an opportune and appropriate time to revisit the Wahlke Report for its relevance as a guide for contemporary political science departments and their faculty and students.

The pandemic and the concomitant rise in unemployment also exacerbates the pressure on universities to prepare students for the labor force with professional skills that often are at variance with the liberal arts focus of the traditional political science major. The restructuring of the economy, including the growth of high-tech firms and advances in the Internet, have created a demand for students with science and engineering backgrounds, which channels many undergraduates into natural and biological sciences, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) majors rather than political science (and the social sciences overall). The increasing demand for STEM majors also has led to declines in funding for the social sciences, including political science, because many larger institutions tie funding for individual departments to the number of student credit hours. In addition to the growth of STEM majors, political science departments are facing more direct competition with the growth of other public-service–oriented undergraduate majors, such as public policy, public administration, and social work. Furthermore, a dramatic decline has occurred in law-school applications and enrollments, which reflects the waning popularity of law as a career. Because political science often is viewed as an important major for law-school preparation, the decline in interest has naturally affected the incentive for undergraduates to major in political science.

To be sure, many exciting opportunities and counter-pressures exist that spark greater interest in political science as an undergraduate major. The election of Donald Trump and America’s polarized politics have led students to enroll in political science courses to gain a greater understanding of politics. Many students volunteer for political candidates, which prompts them to seek more information about elections and government. Political polarization is a contributing factor in the call for more civic education and training of young people to be effective and engaged citizens. The political science major offers civic education through classroom instruction and service-learning and community projects. Furthermore, the study of politics can involve a focus on elections, polling, and citizen surveys, providing an excellent opportunity for students to learn about data analysis, survey and research design, and statistics. Coursework in data analysis also fits with policymakers’ increasing emphasis on marketable skills for undergraduate majors. Finally, globalization, trade wars, and political conflict around the world are spurring great interest in comparative politics, international security, and human rights—all topics potentially central to a political science major. With more competition for funding and students, political science departments have a substantial incentive to innovate and offer new pedagogical options to attract more students and engage them in the policy process.

With more competition for funding and students, political science departments have a substantial incentive to innovate and offer new pedagogical options to attract more students and engage them in the policy process.

The Wahlke Report offered a blueprint for a comprehensive political science major in an era of relative stability in higher education. Today, political science as a discipline must adapt to a vastly altered institutional and social landscape. This article provides an overview and analysis of the trends in the political science major and notable curricular innovations to highlight possible strategies to strengthen its potential impact and scope.

TRENDS IN ENROLLMENTS AND DEGREES AWARDED

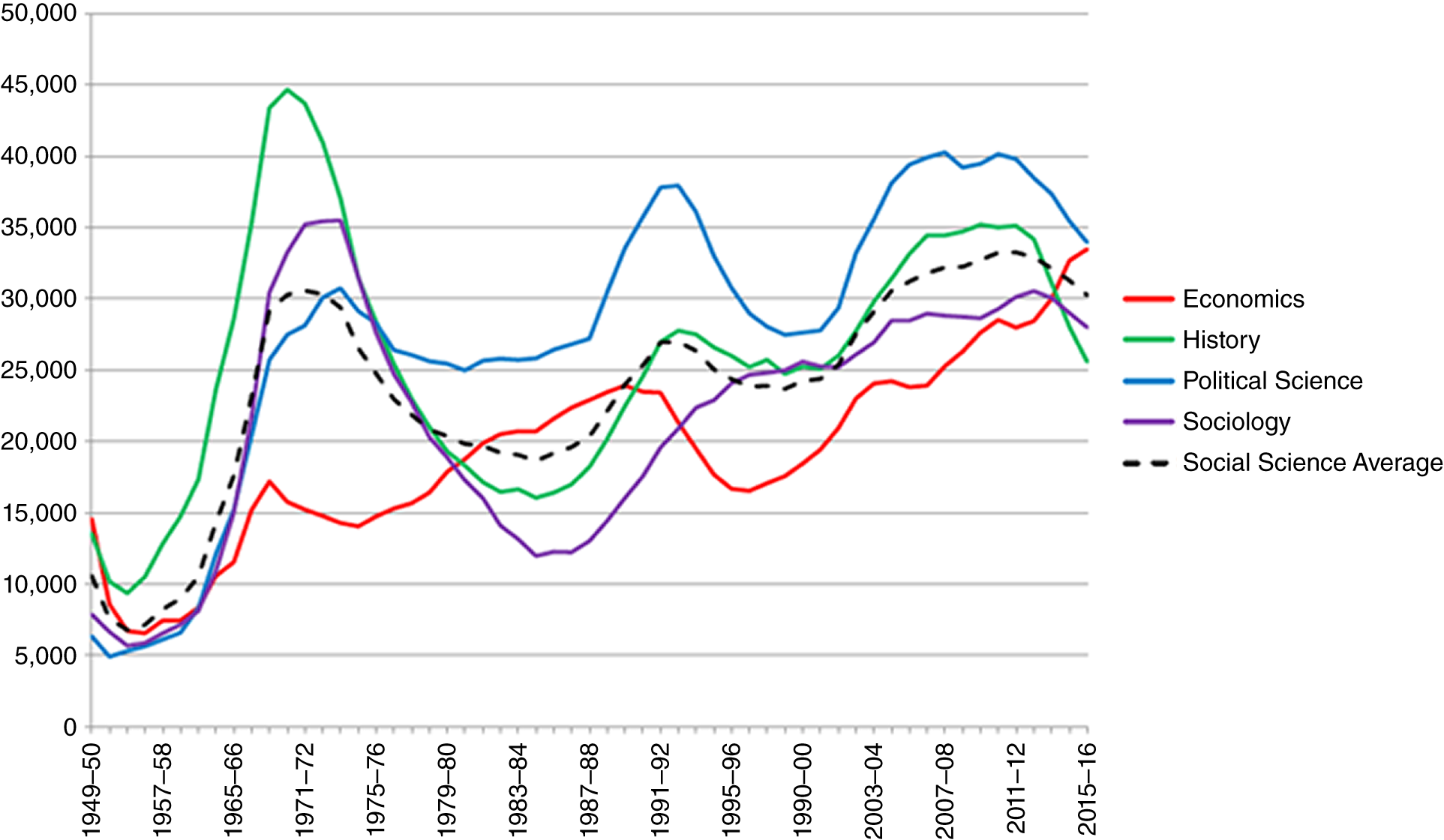

In terms of the total number of undergraduate degrees conferred, political science has experienced a long-term increase during the past 70 years (figure 1). This trend generally mirrors overall trends in social science undergraduate degrees; however, since the 1970s, political science has consistently outperformed the average. After a moderate decline in the late 1990s, the number of political science degrees awarded peaked in 2007–2008 at more than 40,000 but has since declined by more than 15%. This decline is common to most social sciences. Economics is the only exception; the number of undergraduate degrees conferred continues to increase.

Figure 1 Economics, History, Political Science, and Sociology Bachelor’s Degrees Conferred, 1949–2016

Note: Data from the National Center for Educational Statistics Annual Digest of Education Statistics; figure from Jackson Reference Jackson2018.

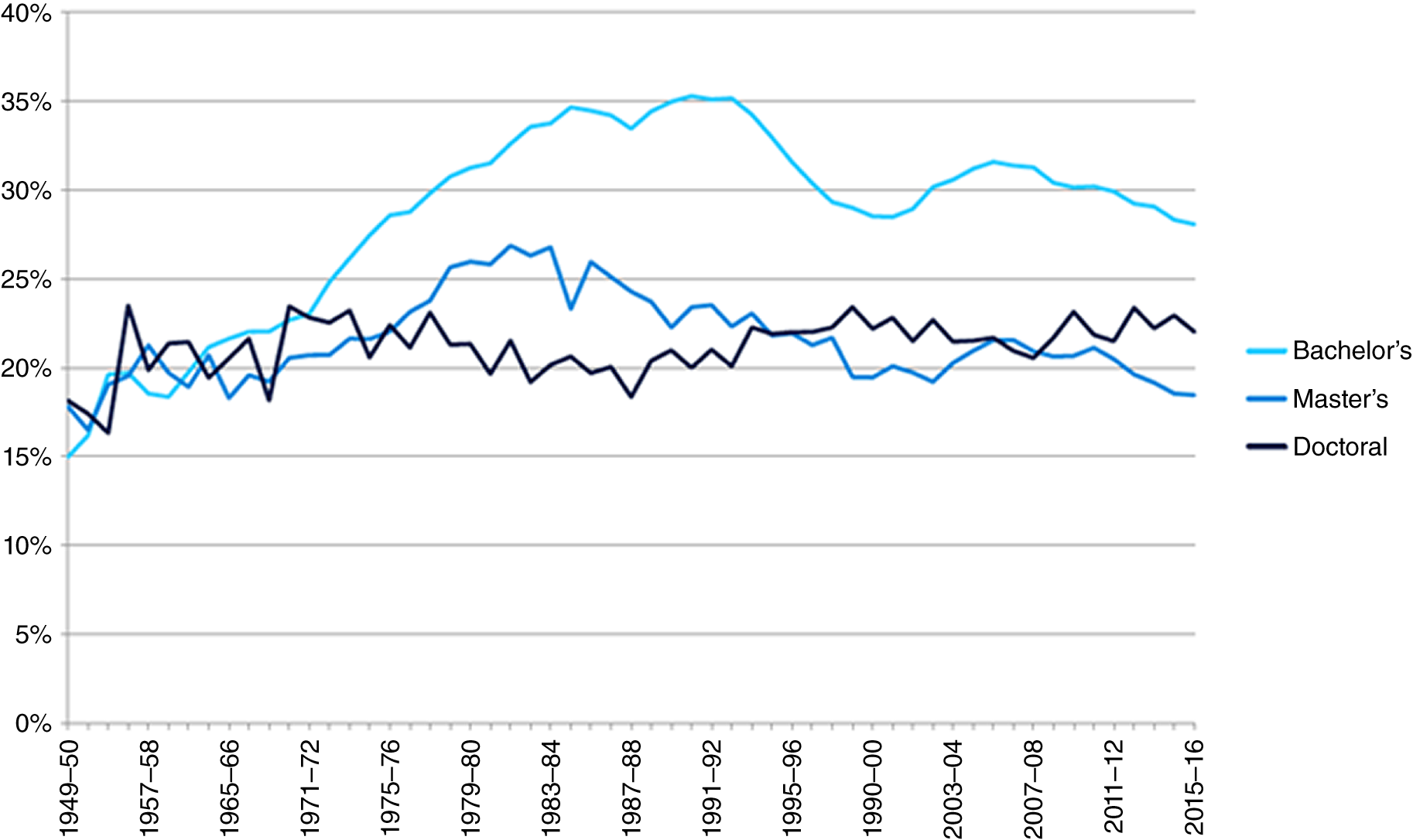

When considering the political science undergraduate degrees as a proportion of all social science undergraduate degrees conferred, the downturn appears to have begun much earlier. The market share for political science undergraduate degrees began eroding by the mid-1990s, after peaking in 1990–1991 at more than 35% of all social science undergraduate degrees conferred (figure 2). Although the decline in political science as a proportion of social science undergraduate degrees has been gradual, and the numbers rebounded slightly in the mid-2000s, this erosion continued in 2015–2016, when political science comprised 28% of all social science undergraduate degrees conferred.

Figure 2 Political Science as a Proportion of All Social Science Degrees Conferred, 1949–2016

Note: Data from the National Center for Educational Statistics Annual Digest of Education Statistics; figure from Jackson Reference Jackson2018.

However, more recent data on enrollments rather than on completed degrees suggest a more positive trend. The APSA departmental survey asks about trends in enrollments, and respondents suggest that the recent uptick in interest in politics translates into increasing enrollments for undergraduate political science departments. When asked about trends between the 2014–2015 and 2015–2016 academic years, 32.7% of department chairs reported a decline in enrollments whereas only 30.7% reported an increase. In contrast, when asked about trends between the 2016–2017 and 2017–2018 academic years, a full 50.3% of respondents indicated that they had seen an increase in undergraduate enrollments. It is unclear whether this trend is sustainable, especially given the pandemic, but the immediate data on enrollments are encouraging. Indeed, anecdotally, many political science departments have experienced a significant increase in the total number of enrolled undergraduate students and the number of majors. Some departments are even effectively at capacity in terms of the number of students that they can teach with available resources. However, these trends in enrollment depend significantly on institution type. Both PhD- and MA-granting universities have most consistently seen increases in enrollments, with more than 60% reporting an increase in enrollments between the 2016–2017 and 2017–2018 academic years. For BA-granting departments, however, the plurality (34.5%) reported that enrollments had remained the same and only 38.7% reported an increase (table 1).

Table 1 Reported Enrollment Changes by Institution Type

Note: Data from table 1 is from Davis, McGrath, and Super 2019.

NEW DIRECTIONS IN UNDERGRADUATE POLITICAL SCIENCE CURRICULUM

To sustain and build on the encouraging trends in undergraduate enrollments in political science, curricula should connect to the increased demand for professional skills and emphasize the particular advantages of the political science major. One overall trend in higher education affecting political science is an increased focus on workplace-relevant skills. For example, a 2016 UCLA Higher Education Research Institute Survey indicated that 85% of first-year students across 184 four-year colleges reported that “to get a better job” is a “very important” reason they attend college (Eagan et al. Reference Eagan, Stolzenberg, Zimmerman, Aragon, Sayson and Rios-Aguilar2016). However, majors in arts and sciences (i.e., arts and humanities, biological sciences, physical sciences, and social sciences) reported fewer work-related skills than those in professional fields (i.e., education, health, and business) (Indiana University 2018). Furthermore, social science faculty are relatively unlikely to “substantially structure courses for job- or work-related knowledge and skills” (slightly more than 50%). Seniors in arts and humanities, biological sciences, and social sciences, as well as seniors who participated in service learning, also are more likely to have “unconventional immediate” career plans (i.e., internship, travel/gap year, and service/volunteering) (Indiana University 2018).

These characteristics of social science majors, including political science, comprise one factor in the increased competition for students encountered by political science and other social science departments. Yet, the social sciences—and political science in particular—have important comparative advantages to attract students. Social science, communications, education, and social services majors report greater skills in understanding people of other backgrounds, a valuable skill given the increasing diversity of the workforce (Indiana University 2018). More generally, social science and humanities fields tend to be more successful in teaching students how to communicate effectively and to work with other people. To be sure, the social sciences face a marketing problem because these “softer” job skills often are compared unfavorably to job skills such as quantitative reasoning or specific scientific knowledge such as engineering. However, these interpersonal skills are increasingly critical to successful job performance.

To be sure, the social sciences face a marketing problem because these “softer” job skills often are compared unfavorably to job skills such as quantitative reasoning or specific scientific knowledge such as engineering. However, these interpersonal skills are increasingly critical to successful job performance.

Another comparative advantage for the social sciences is effective writing. For instance, seniors in social sciences, communications, arts and humanities, and social services reported gaining more skills in writing than the average senior (Indiana University 2018). The emphasis on writing in the political science major—especially in upper-division courses—is a valuable benefit of the major.

Political science offers support for civic skills and education, which can be another advantage. The push for civic education has several sources. A preparedness study by Bentley University (2014) suggested that employers want employees with civic skills. Moreover, new criteria for accreditation (effective in 2020) from the Higher Learning Commission (2019)—the accrediting body for universities in a 19-state region in the Midwest—includes specific encouragement for activities that promote informed citizenship and workplace success. One national organization, the Students Learn Students Vote Coalition (2019), argues for more “democratic engagement” at universities, including student participation in communities and applied learning. Matto et al. (Reference Matto, McCartney, Bennion and Simpson2018) also argued that teaching civic engagement can “impart…skills to peacefully and constructively access [our democratic systems].” To be sure, civic skills can be obtained through a variety of curricular offerings, especially outside of the classroom (Matto Reference Matto2019), including internships and service-learning opportunities. However, political science departments remain a key driver of civic education.

Importantly, recent curricular innovations in the political science major at different universities may suggest possible avenues for departments to pursue to enhance their relevance to contemporary undergraduate students while also providing a solid grounding in the liberal arts. One approach to change is to emphasize a common core that includes a strong analytics component with strong concentrations and subfields. For example, the University of California–San Diego now has seven different political science concentrations, including data analytics (a BS degree). All majors are required to take a course in methods and three or four courses in American politics, international relations, comparative politics, and power and justice. The UCLA political science department has a required statistics course and six concentrations, including methods and race, ethnicity, and politics. Stanford and Duke have undertaken similar curricular changes.

Other departments emphasize civic engagement and service learning as part of their overall major requirements. For instance, the University of Illinois restructured its major to emphasize a choice of six concentrations, including civic leadership, citizen politics, and public policy and democratic institutions. Other universities (e.g., San Jose State) changed their major requirements to allow more opportunity for service learning and projects outside of the classroom.

Despite differences in content, many of these curricular innovations share the goal of providing more topical content that connects students to the real world of policy and politics. Larger departments can offer much greater choice in courses, but the lessons on relevance remain widely applicable across different institutions.

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

Given the current pandemic, great uncertainty regarding instruction, student enrollments, and university budgets is likely to be with us for some time. Thus, the structure, comprehensiveness, and sequencing of the political science major in the recommendations of the Wahlke Report are likely to be elusive. More flexibility in curriculum and creative pedagogical strategies in an era of online education are likely to be necessary to attract and retain students. Nonetheless, the emphasis in the Wahlke Report on greater responsiveness to students, more intensive instruction in data analysis, and the need to adapt the major to be more diverse and inclusive are profoundly important goals in the present era. The Wahlke Report placed a priority on political science as a liberal arts major that also provided valuable civic knowledge and employment skills, which remain strengths of the major today. Consequently, the political science major continues to have significant strengths to prepare informed citizens and productive and effective employees.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors express their gratitude for the assistance and feedback of John Ishiyama and the attendees of the June 2019 workshop at the University of North Texas, as well as Megan Davis, Amanda Grigg, Erin McGrath, Kim Mealy, Tanya Schwarz, and Betsy Super at APSA in the preparation of this article.