Variations in state campaign finance regulations across states and over time provide an opportunity to test the effects of reforms on the electoral success of incumbent state legislators. We use the most recent state legislative election returns dataset to test whether state campaign finance reforms help or hinder incumbents. Our analysis of nearly 66,000 contests in 33 years reveals that campaign contribution limits and partial public financing have little impact on incumbent reelection prospects. However, full public financing and prohibitions on corporate independent expenditures significantly increase the probability of incumbent reelection.

Do campaign finance reforms increase electoral competition or further entrench incumbents? Most of the literature on the electoral effects of campaign spending suggests that challengers have a higher marginal benefit from expenditures, even if only because—on average—they tend to spend much less than incumbents (for a review of this literature, see Milyo Reference Milyo2013). Consequently, to the extent that some regulations (e.g., contribution limits) aim to reduce campaign spending by candidates, it follows that such reforms may hinder challengers and augment the already formidable advantages of incumbency.

Conversely, prominent pro-reform interest groups argue that state campaign finance reforms enhance electoral competition (Lioz and Wright Reference Lioz and Wright2006; Torres-Spelliscy, Williams, and Stratmann Reference Torres-Spelliscy, Williams and Stratmann2009). These claims are bolstered by several empirical evaluations of state reforms in practice (Gross, Goidel, and Shields Reference Gross, Goidel and Shields2002; Stratmann Reference Stratmann2010; Stratmann and Aparicio-Castillo Reference Stratmann and Aparicio-Castillo2006; see also La Raja and Schaffner Reference Raja, Raymond and Schaffner2014). However, of these studies, only Stratmann (Reference Stratmann2010) and Stratmann and Aparicio-Castillo (Reference Stratmann and Aparicio-Castillo2006) controlled for state fixed effects, although neither controlled for partisan tides across election years; neither did they examine campaign finance regulations other than contribution limits. Moreover, none of these studies controlled for district-level fixed effects or the potential effects of redistricting on incumbent electoral success. Furthermore, all of these studies examined election data previous to the controversial 2010 Citizens United case.

We reexamined whether campaign finance reforms help or hinder incumbent reelection in state legislative elections using data through the 2018 election cycle. Furthermore, we incorporated a broader set of state campaign finance regulations than previous authors while also controlling for district-level fixed effects as well as partisan tides across years. Consequently, our analysis addresses several shortcomings in the existing empirical literature on the effects of state campaign finance reforms on electoral competition in state legislative elections.

It therefore is not surprising that our findings contrast with prior studies that examined the effects on electoral competition of state campaign finance reforms in practice. Overall, we found no support for the claim that reforms benefit challengers in state legislative elections. In particular, contribution limits and partial public financing appear to have negligible effects on electoral competition. However, we observed strong pro-incumbent effects from both full public financing and prohibitions on corporate independent expenditures.

DATA AND METHODS

We exploited the variation in state campaign finance laws across states and time to identify the effects of reforms on the competitiveness of incumbent reelection contests.

We exploited the variation in state campaign finance laws across states and time to identify the effects of reforms on the competitiveness of incumbent reelection contests.

This natural experiment approach to understanding the effects of state campaign finance reforms was implemented in several recent studies (Flavin Reference Flavin2015; Klumpp, Mialon, and Williams Reference Klumpp, Mialon and Williams2016; Primo and Milyo Reference Primo and Milyo2006; Reference Primo and Milyo2020; Primo, Milyo, and Groseclose Reference Primo, Milyo, Groseclose and McDonald2006; Stratmann Reference Stratmann2010; Stratmann and Aparicio-Castillo Reference Stratmann and Aparicio-Castillo2006).

We used the most recent version of the state legislative election returns data compiled by Klarner (Reference Klarner2019) to identify all general election races involving incumbents running for reelection in single-member districts. We then eliminated contests with multiple incumbents running for the same seat or with no major-party incumbent, which includes all contests for the nonpartisan legislature in Nebraska. Finally, we restricted the period to 1986–2018 to match the time span covered by our campaign finance data. This selection process resulted in almost 66,000 state legislative races.

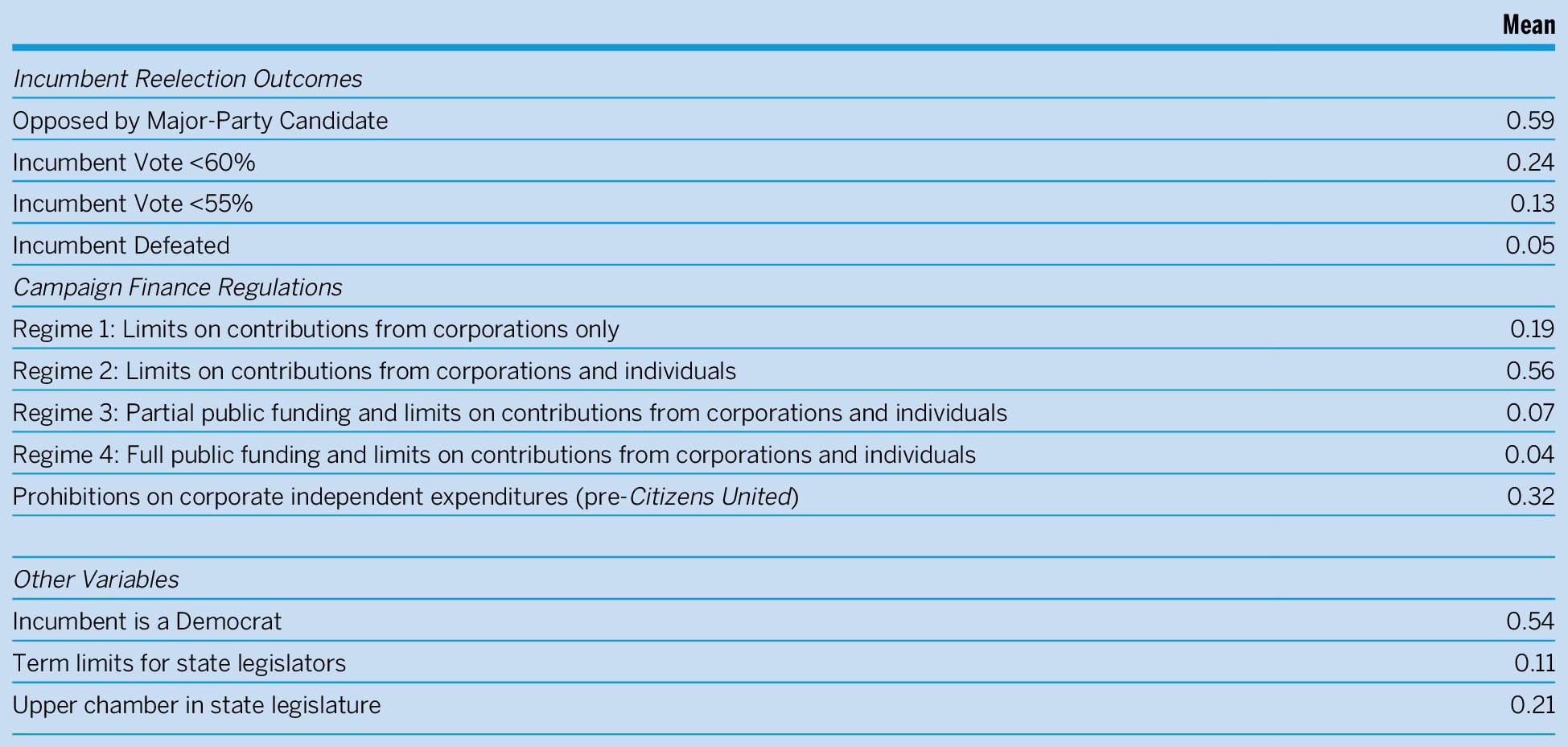

The upper panel of table 1 describes the dependent variables that we examined. Each represents a different way to characterize the competitiveness of incumbent reelection races. These include whether the incumbent faced a major-party challenger; whether the incumbent’s vote was less than 60% or 55%; and whether the incumbent was defeated. In the 33 years covered by our study, fewer than 60% of incumbents were challenged by a major-party candidate (i.e., Democrat or Republican) and less than 25% (i.e., 15%) of incumbents were held under 60% (i.e., 55%) of the votes cast in their race. However, the most telling statistic is that only 5% of state legislative incumbents running for reelection were defeated in the general election. Consequently, because the base rate is so low, even a small change in the probability of incumbent defeat may lead to a relatively large change in the frequency of incumbents defeated.

Table 1 Descriptive Statistics for State Legislative Elections, 1986–2018

Notes: N=65,979. The sample includes all general-election races in single-member districts with a major-party incumbent running for reelection (races with multiple incumbents or in Nebraska are omitted).

We estimated the effects of state campaign finance reforms on each measure of competitiveness via linear probability models (i.e., for ease of exposition and to facilitate the interpretation of fixed effects). To control for anti-incumbent and partisan tides in any given election year, all specifications include indicators for year, as well as the year interacted with whether the incumbent was a Democrat. All specifications also include indicators for state-legislative districts to control for unobserved district-level fixed effects.Footnote 1 We also adjusted estimated standard errors for clustering by state (Primo, Jacobsmeier, and Milyo Reference Primo, Jacobsmeier and Milyo2007).

The key independent variables of interest in our analysis are indicators for state campaign finance regulations (see the middle panel of table 1). We followed a previous study (Primo and Milyo Reference Primo, Milyo, Groseclose and McDonald2006) and focused on state laws that limit contributions to candidates from corporations and individuals or that provide some type of public funds for state legislative candidates. All data on state campaign finance laws are from Primo and Milyo (Reference Primo and Milyo2020).

One advantage of this approach is that state campaign finance regulatory regimes then can be characterized in one of five mutually exclusive categories. We included five indicators for each regime: (1) limits on contributions to candidates from corporations; (2) limits on contributions to candidates from corporations and individuals; (3) states with limits on contributions and partial public funding for state legislators; (4) states with limits on contributions and full public funding (i.e., “clean-money” reforms); and (5) states without limits on contributions and no public funding. The fifth regime is the omitted category in our analysis, and the presence or absence of any of the other four regimes is described with binary indicator variables. Table 2 is a breakdown of regulatory regimes by state over time.

Table 2 Campaign Finance Regulatory Regimes, 1986–2018

Note: See table 1 for definitions of campaign-finance regulatory regimes.

Slightly less than 15% of races occur in states that do not limit contributions to candidates (i.e., the omitted regime category), whereas almost 20% of races occur in states that limit only contributions to candidates from corporations (i.e., regime 1). However, the most common regulatory regime imposes limits on contributions from both corporations and individuals (and with no public financing); that is, more than half of all incumbent reelection races occur under these regulations (i.e., regime 2).

Public funding occurs only in states that also limit both corporate and individual contributions (i.e., about another 10% of the contests in our sample), although public-funding schemes in the states come in two variations. Earlier adopters of public funding (e.g., Hawaii, Minnesota, and Wisconsin) provided limited matching grants to candidates conditional on adherence to a ceiling on candidate spending (i.e., regime 3). These “partial-funding” reforms have since given way more recently to so-called clean money reforms in Arizona, Connecticut, and Maine (i.e., regime 4). These states provide “full” public financing to candidates who can raise sufficient seed money from small donations and agree not to supplement their campaign spending with funds from private contributors. Of course, public funding of either type is voluntary in that candidates may opt out and fund their campaigns entirely through private donations.Footnote 2

Whereas the campaign finance laws described previously occur in five mutually exclusive regulatory regimes (captured with four indicator variables), the same is not true for prohibitions on corporate independent expenditures. Before the 2010 US Supreme Court decision in Citizens United, almost half of the states prohibited independent expenditures by corporations in support or opposition of state legislative candidates (Klump, Mialon, and Williams Reference Klumpp, Mialon and Williams2016). Consequently, we included a separate indicator for the presence of prohibitions on independent expenditures by corporations, which encompasses almost one third of the contests in our sample.

Finally, we included indicators to control for the presence of legislative term limits in a state. Data on state-legislative term limits are from the National Conference on State Legislatures. Descriptive statistics for this variable, as well as the share of races involving the upper chamber of the state legislature or with Democratic incumbents, are shown in the lower panel of table 1. However, these last two variables are subsumed by the inclusion of fixed effects for legislative districts and (party of the incumbent X year) in subsequent regression models.

RESULTS

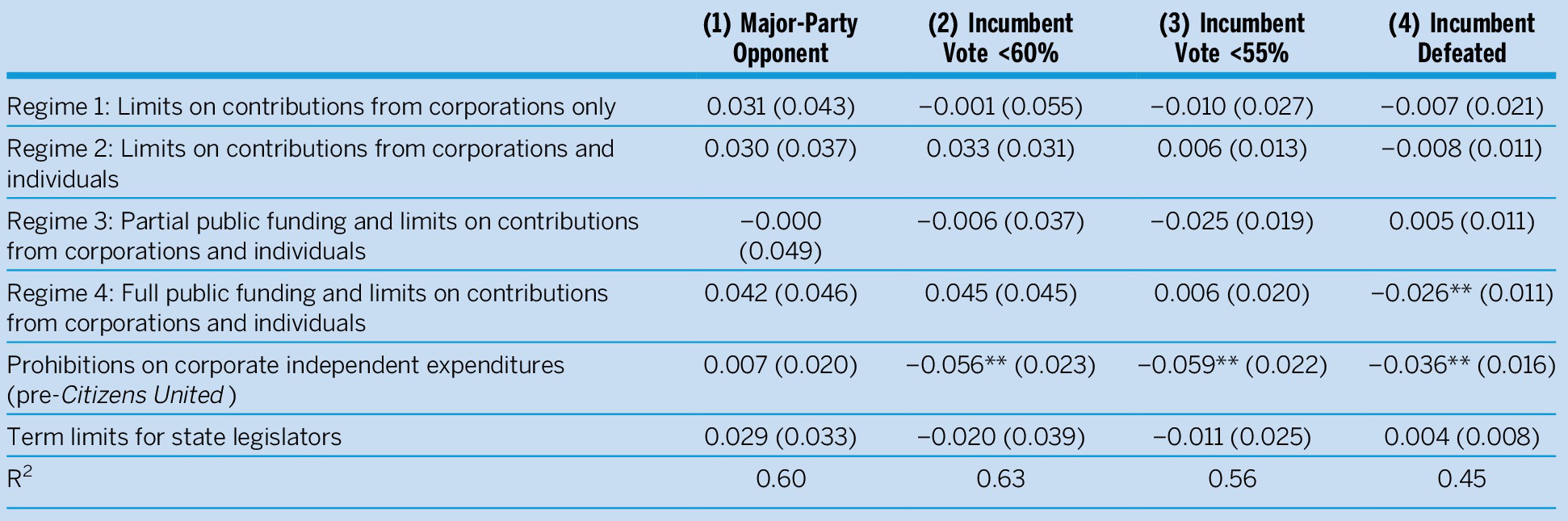

The coefficient estimates of interest are listed in table 3. The columns list results from separate regression models for each dependent variable, with standard errors adjusted for clustering at the state level in parentheses. For example, the last row of estimates reveals that legislative term limits do not have a statistically significant effect on electoral competition in any of the four models.

Table 3 Incumbent Performance in State Legislative Elections, 1986–2018

Notes: ***p<0.01, **p<0.05, and *p<0.10. Estimated coefficients from linear probability models (standard errors corrected for clustering by state). All models include indicators to control for (party of incumbent X year) effects and district-fixed effects.

The results in column 1 show no statistically significant effects of contribution limits, public financing, or limits on corporate independent expenditures. Whereas most of the estimated coefficients of interest in the initial model are positive (suggesting pro-challenger effects of reforms), tests of the joint significance of these estimates reveal that we cannot reject the null hypotheses that all four campaign finance regime indicators are (1) identical, and (2) zero. The same is true for joint-significance tests of all five campaign finance indicators when the effects of independent expenditure limits also are included.

Columns 2 and 3 in table 3 report results for different measures of competitiveness based on an incumbent’s percentage of the total vote. In each case, the signs on the campaign finance regime indicators are mixed and statistically indistinguishable from zero. In fact, in neither model can we reject the null hypotheses that all four regime indicators are (1) identical, and (2) jointly zero. In contrast, in both of these models, prohibitions on corporate independent expenditures appear to be strongly anti-compeoititive, reducing the probability of a tight race by about 6 percentage points (compared to baseline probabilities of 0.24 and 0.13, respectively).

Finally, we examined the probability that an incumbent is defeated for reelection in column 4 of table 3. On average, only 5% of state legislative incumbents are defeated in general-election races. In this last model, the estimated coefficients for regulatory regimes 1–3 are small and statistically insignificant (both individually and jointly). However, full public funding (i.e., clean money reforms) now reduces the probability that an incumbent is defeated by almost 2.6 percentage points (p<0.05). This effect is rivaled by the impact of prohibitions on corporate independent expenditures, which reduce the probability of incumbent defeat by 3.6 percentage points (p<0.05). The estimated effects of full public financing and bans on corporate independent expenditures also are jointly significant (p<0.01).

We compared the robustness of these results to several alternative specifications. For example, examining only races for legislative seats in the lower chamber of state legislatures yields similar findings. We also obtained a similar pattern of results when we replaced district-level fixed effects with (state X decade) indicatorsFootnote 3 or even including only state-specific fixed effects. Likewise, adjusting standard errors for clustering by state and decade did not alter our main findings.

Nevertheless, our analysis has limitations. For example, we examined only the presence of contribution limits, not whether such limits are set relatively high or low. Furthermore, our analysis follows the previous literature by examining the competitiveness of races given that an incumbent is running in the general election. It is possible that campaign finance regulations may influence the choice of incumbents to stand for reelection or their success in primaries antecedent to the general election. Future work should consider this potential source of sample-selection bias.

DISCUSSION

We examined the effects of various state campaign finance reforms on several measures of the competitiveness of incumbent reelection contests from 1986 to 2018 using the most recent state legislative elections-returns dataset (Klarner Reference Klarner2019). In contrast to previous studies, we examined a broad set of campaign finance regulations and controlled for both (year X party) effects and district-level effects.

Our results suggest that state campaign finance regulations have no significant impact on the probability that an incumbent state legislator is opposed by a major-party challenger. Neither do contribution limits or public-financing regimes have a significant effect on the incidence of close elections (i.e., incumbent vote share less than 60% or 55%). In contrast, prohibitions on corporate independent expenditures do have a significant and detrimental impact on the competitiveness of state legislative elections, decreasing the probability that the incumbent vote share is less than 60% (or 55%) by almost 6 percentage points. This effect is significant given the infrequency of such close races when incumbents run for reelection.

Of particular interest is how campaign finance reforms affect incumbent reelection rates. Our results show that contribution limits and partial public financing do not help challengers in their quest to defeat incumbents. Moreover, full public financing (i.e., clean money reforms) reduces the probability that an incumbent state legislator is defeated by 2.6 percentage points. Likewise, prohibitions on corporate independent expenditures pre-Citizens United not only reduced the frequency of tight elections; they also lowered the probability of incumbent defeats by 3.6 percentage points. These unintended effects (or unexpected, at least among pro-reform interest groups) are significant given that only 5% of incumbents running for reelection were defeated in the 33 years of state legislative elections examined in this study.

These results stand in contrast to erstwhile arguments for campaign finance reform and much of the popular angst directed at the Citizens United decision.

These results stand in contrast to erstwhile arguments for campaign finance reform and much of the popular angst directed at the Citizens United decision.

Rather than enhancing competition, clean money reforms appear to further entrench incumbents—and rather than hinder electoral competition, the Citizen United decision significantly reduced the incumbency advantage in state legislative elections.