How ought we understand the Trump era? How can we make sense of the White House’s actions? These questions are important not only for scholars of American politics but for anyone who wants to understand current United States policy. Journalists, politicians, and scholars have all provided a number of perspectives on Trump’s government. While many of them are useful, we have found them incomplete. We provide a different outlook in this Spotlight, which includes several essays that examine recent events in American politics through the lens of the contentious politics literature. These short pieces provide new insights into current events in the United States, offer activists suggestions for real-world action, and suggest several new research directions for scholars of American politics.

We begin the Spotlight with a discussion of how the terms “repression,” “oppression,” and “discrimination” have recently been used in popular outlets. We then outline a conceptual map that journalists and academics can reference when classifying government actions. The idea here is to develop a uniform vocabulary that can be used to describe instances of unjust treatment or control by the government.

The next set of contributions focuses on the similarities between the current administration and autocracies. Erica Chenoweth compares Trump’s administration to other authoritarian regimes. She describes the strategies used by autocrats to deter opposition—a set of measures collectively referred to as the “anti-revolutionary toolkit”—and provides examples of their use under the 45th president. Chenoweth finishes by outlining several recommendations for members of the nonviolent resistance and offers some suggestions for scholars.

In a similar vein, Dana Moss illustrates the degree to which Trump’s administration has adopted authoritarian styles of rule. Specifically, she demonstrates that the White House has adopted three strategies of governance common to autocracies in the Middle East: “negative othering,” “dishonoring,” and “loyalist counter-mobilization.” Moss ends by enjoining researchers to engage in more comparisons between the style used by the American government and regimes in other parts of the world.

Another pair of contributions focuses on specific human rights threats. First, Jennifer Earl evaluates and contextualizes the multiple threats to media freedom that have occurred throughout 2017. She argues that prior work has largely missed the point of these attacks on the first amendment—they are not merely designed to control information access but to control the construction of reality itself. Earl calls for greater attention to this threat by journalists and researchers alike.

Second, Emily Ritter applies the principal-agent framework to the Trump administration’s immigration policies. She argues that the discretionary power provided by new immigration rules coupled with adverse selection issues in agent recruitment combine to increase the likelihood of human rights violations. Ritter closes by offering a few suggestions about how this possibility can be decreased.

Finally, Christopher Sullivan examines challenges to activism in the age of mass surveillance. Drawing from the example of Occupy Wall Street, he argues that activists can counter increased government intelligence capability through “concealment” and “obfuscation” but that the government can counter these strategies through “disruption” and “screening.” He concludes by stressing that activists must develop new means of concealment and obfuscation if they want to maintain the possibility of mounting behavioral challenges.

We would like to thank PS: Political Science & Politics for providing us with the opportunity to organize this Spotlight. We also want to thank the contributors to this Spotlight for writing and submitting fantastic work under tight deadlines. Finally, we wish to thank PS’s editorial team for their crucial help in organizing, editing, and finalizing this set of essays. We hope that they are the first foray in a larger conversation between scholars of contentious politics and American politics. We dedicate this Spotlight to Will Moore.

DEFINING THE TERMS OF DEBATE: REPRESSION, OPPRESSION, AND DISCRIMINATION

Since the beginning of the 2016 presidential campaign, American concern over domestic repression has grown considerably. This trend can be directly observed in the frequency with which residents of the United States have searched for the term “repression.” As figure 1 shows, mass interest in this phrase rose dramatically in the days immediately before and after the November election and also at various other points since President Trump took office. This interest is reflected in the increased media coverage of potential and real repressive acts by the US government. It can also be seen in the proliferation of scholarly “think pieces” in mass-market newspapers and journals, such as the New York Times and The Atlantic, or academic blogs, such as the Monkey Cage or Political Violence @ a Glance, that speculate as to the degree that the federal government might engage in repressive activity or seek to classify policy changes as instances of repression.

Figure 1 Google searches for “repression,” “oppression,” and “discrimination” in the United States, 06/2016-05/2017

Figure 1 indicates the frequency with which individuals in the United States used Google to search for the terms “repression” (solid red line), “oppression” (dotted blue line), and “discrimination” (dashed grey line). The vertical axis in each panel, Google search popularity, is scaled from 0 to 100, so that 100 represents the highest number of searches in a month that were conducted for one of the three terms during the 06/2016–05/2017 period. The number of searches per week for each term are then measured relative to this “highest” value.

The increased popular interest, media coverage, and academic writing on this important type of state behavior is most welcome. It has been particularly heartening to see scholars of American politics author popular works that focus on repression, a topic which has largely been the domain of individuals in comparative and international relations or within the field of sociology connected with social movement research. Interest from Americanists is especially useful because their potential contributions could enliven the literature and lead to a more nuanced understanding of repression’s causes and consequences in an advanced democracy. Unfortunately and crucially, this has been a context often ignored by repression scholars.

In the interests of trying to help all those who have now decided to make contributions in this field—particularly those working in the media—we have identified one potential problem with recent works on repression in the American context. The issue here is that they often use the term “repression” in a non-standard way, sometimes even confusing it with two other related concepts: “oppression” and “discrimination.” Footnote 1 At the moment, this potential problem has primarily appeared in non-peer-reviewed pieces, but we want to address this concern before it affects academic work as well—interjecting earlier as opposed to later.

Our chief concern is that inconsistent use of this term can lead to unintentional conceptual stretching (Sartori Reference Sartori1970). By including a large range of activities under any conceptual label, we can potentially discuss more different instances of that thing. But as Sartori (Reference Sartori1970) warned us nearly 50 years ago, we ultimately wind up “saying less, … and saying less in a far less precise manner” (1035). Another related concern is that by using “repression” in different ways, scholars new to this topic might accidentally prevent scholarly accumulation and synthesis by creating a conceptual wedge between researchers. A third concern is that it is simply inefficient for researchers to spend time creating new meanings for a well-defined concept.

In light of these concerns, we want to re-introduce a widely-adopted definition of repression and discuss how that concept relates to oppression and discrimination. Our hope is that the brief conceptual map we introduce here can be used by media members and scholars who are now starting to write about repression. The ultimate goal of this piece is to encourage more and better work on the subject.

Essentially, we follow Goldstein (Reference Goldstein1978)—and thus the majority of the literature—by defining repression as “the actual or threatened use of physical sanctions against an individual or organization, within the territorial jurisdiction of the state, for the purpose of imposing a cost on the target as well as deterring specific activities and/or beliefs perceived to be challenging to government personnel, practices or institutions” (xxvii). Based on this definition, the two key features of repression are (1) that it involves the threat or application of physical violence and (2) that it is meant to deter political opposition (in action or thought). While recent contributions to the repression literature have begun to expand the type of state activity included under this definition so that it also includes violations of civil (or empowerment) rights, there is near consensus in the literature that a state only engages in “repression” if its acts are intended to undermine possible threats to its rule.

But how do we describe state actions that threaten or apply harm for some other purpose? In this case, scholars typically use the term “oppression.” While there is no canonical definition for this term, it is commonly used to describe violent behavior by the state that does not target individuals or groups for political purposes. Footnote 2

One way of viewing these different concepts is as subtypes of discrimination. According to the United States Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, discrimination involves treating someone unfavorably because of his or her group membership. Footnote 3 Individuals can be discriminated against based on their affiliation with political or non-political groups (e.g., party, sex, race). Viewed in this light, repression can be considered as violent discrimination against individuals based on the political group to which they belong. Similarly, oppression can be seen as violent discrimination against individuals based on other group-level characteristics. Crucially, however, “discrimination” departs from the typical conceptualization of “repression” and “oppression” by describing both violent and non-violent actions.

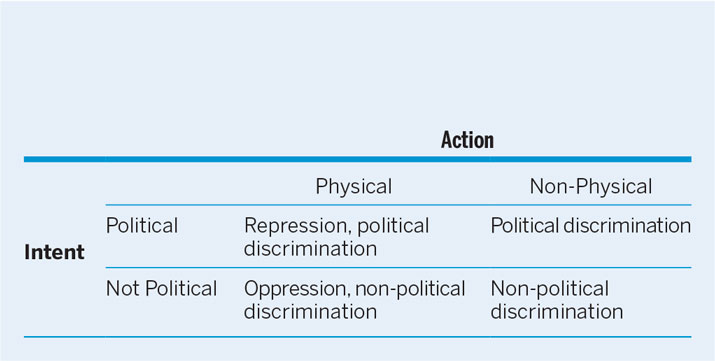

This description of these terms suggests that state actions can be classified based on two dimensions. The first dimension relates to the intent of state action. The second dimension captures the type of action. Table 1 presents this classification. We hope that it aids journalists and researchers as they seek to classify actions by the United States and other states.

Table 1 Categorizing Action and Intent

THE TRUMP ADMINISTRATION’S ADOPTION OF THE ANTI-REVOLUTIONARY TOOLKIT

Increasing oppression often provokes resistance (Chenoweth and Ulfelder Reference Chenoweth and Ulfelder2017)—and dissent typically provokes repression (Davenport Reference Davenport2007; Ritter and Conrad Reference Ritter and Conrad2016). Since January 20, 2017, activists and organizers in the United States have engaged in protests, strikes, demonstrations, road blockades, sit-ins, and a wide variety of other methods of resistance. In response, rather than using the bluntest instruments of state power to violently suppress these activities, the Trump administration has wittingly or unwittingly borrowed best practices in anti-revolutionary repression from authoritarian regimes.

Indeed, scholars identified this “anti-revolutionary toolkit” (see table 2)—a tactical repertoire of smart repression—as an emergent phenomenon in authoritarian and semi-authoritarian regimes in the wake of the Color Revolutions of the mid-2000s (Spector Reference Spector2006; Spector and Krikovic Reference Spector and Krickovic2008). The toolkit’s widespread adoption is indicative of a realization that the battle for state control is less about the exertion of force and more about the establishment of legitimacy and consent (Arendt Reference Arendt1970; Spector Reference Spector2006). In fact, using brutal repression against opposition often backfires, further de-legitimizing the regime and increasing mobilization against it (Martin Reference Martin2007).

Since January 20, 2017, activists and organizers in the United States have engaged in protests, strikes, demonstrations, road blockades, sit-ins, and a wide variety of other methods of resistance. In response, rather than using the bluntest instruments of state power to violently suppress these activities, the Trump administration has wittingly or unwittingly borrowed best practices in anti-revolutionary repression from authoritarian regimes.

Table 2 The Anti-Revolutionary Toolkit under the Trump Administration

Source: Adapted from Chenoweth Reference Chenoweth2017, 94.

To avoid backfire, authoritarian regimes have explicitly adopted this repertoire as a best practice in suppressing otherwise popular dissent in places as diverse as China, Turkey, Brazil, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Egypt, Iran, Venezuela, and elsewhere (Spector and Krikovic Reference Spector and Krickovic2008). And of course, the anti-revolutionary toolkit is not exclusive to authoritarian regimes; the Federal Bureau of Investigation used many of these techniques to demobilize Black Nationalist organizations in the United States during the 1960s and 1970s (Davenport Reference Davenport2015). Moreover, some elements of this toolkit were operative under the Obama administration in relation to Occupy Wall Street, Black Lives Matter, and Standing Rock.

As an empirical matter, several research practices prevent scholars from systematically evaluating the effects of the anti-revolutionary toolkit on mobilization. First, data on human rights violations and repression is rarely inclusive of both tangible and rhetorical devices—both of which are essential to the functioning of the toolkit. Second, most repression data is not disaggregated to the events level, meaning that it is difficult to disentangle the dynamics of dissent and repression on a granular level. Furthermore, most data do not include information about ways that states attempt to concede or conciliate as a method of dividing the opposition or winning over third parties at the same time as they suppress intransigent dissidents. Therefore, scholars of human rights and repression should expand the types of sources of data and levels of analysis available for systematic evaluation of the toolkit’s effects.

What are the implications for those attempting to organize effective nonviolent resistance against the Trump administration’s agenda? As a practical matter, because of the toolkit’s widespread adoption around the world, countless activists from other contexts possess considerable experience waging nonviolent struggle against regimes employing the toolkit against them. In fact, there have been more active mass nonviolent campaigns in the current decade than in any time in recorded human history (Chenoweth Reference Chenoweth2017). As such, if a global network of regimes has adopted an anti-revolutionary toolkit as a standard tactical repertoire, then US organizers and activists could participate in and cultivate a global network to develop and share strategies, tactics, and lessons from semi-authoritarian contexts regarding how to effectively confront the toolkit.

ENTER A NEW REGIME? LESSONS FROM THE STUDY OF AUTHORITARIANISM FOR US POLITICS

Since the 2016 election of Donald Trump, many scholars and pundits have argued that the current administration poses an existential threat to democracy. But has the United States become, or is it becoming, something new? Certainly, President Trump’s populist and personalistic tendencies, the power and access granted to his family members, the melding of his corporate empire with political authority, his administration’s ties with the Russian regime under Vladimir Putin, and his open admiration of dictatorships—to name just a few examples—do indeed indicate a dangerous turn. But how should researchers assess the changes wrought by this administration (or any other, for that matter) without appearing alarmist on the one hand, or underestimating their significance on the other? Put another way: how exactly are we to know when our political system has become authoritarian?

Rather than trying to decide the time, place, or decision at which some radical transformation has taken place, I suggest that we instead consider how authorities are adopting and amplifying authoritarian styles of rule (Boudreau Reference Boudreau2004). By styles, I mean the deployment of rhetoric, policies, and practices that curtail political rights and civil liberties in an observable way, whether for specific groups or for the population in full. This is a helpful approach for several reasons. First, it enables us to identify how authorities undermine democratic freedoms without overstating the new-ness of these strategies. State leaders do at times innovate and enact new tactics, but they also use illiberal modes of governance already in practice and resuscitate methods with long, infamous track records. Second, we can come to apply lessons gleaned from the study of authoritarianism in other contexts to identify the styles at play here at home. In my research on authoritarianism in the Middle East (Moss Reference Moss2014), for example, I find that authorities use a range of softer and harder repressive methods in a complementary fashion to counter their critics, and below I discuss three such strategies that warrant attention in the United States today.

Negative othering refers to the state-led slander of racial, ethnic, and religious identity groups as inherently foreign, and thus threatening to (purported) national values and security. The Trump administration’s rhetoric and policies targeting non-white immigrants, Muslims, Arabs, Latinos, and others has cast marginalized minorities as un-American, un-assimilable, and threats to the public order.

One authoritarian style, which is virtually timeless in the practice of divide-and-rule, is what I call “negative othering.” Negative othering refers to the state-led slander of racial, ethnic, and religious identity groups as inherently foreign, and thus threatening to (purported) national values and security. The Trump administration’s rhetoric and policies targeting non-white immigrants, Muslims, Arabs, Latinos, and others has cast marginalized minorities as un-American, un-assimilable, and threats to the public order. By declaring them as fifth columns and as threats for anti-Americanism, our leaders suggest that minority immigrants and American citizens alike warrant persecution as if they were foreign combatants in our numerous wars overseas. Importantly, political authorities need not invent new modes or methods of negative othering. Instead, they can merely capitalize on preexisting divisions and amplify them in ways that glorify the old days and the old ways. Doing so justifies increased surveillance, deportations, and violence, as well as denigrating encounters with law enforcement on the streets and at border checkpoints. Negative othering in the Trump era has also re-validated ethno-centrism and given new life to white-Christian supremacists, signifying the resuscitation of a well-worn and deeply American authoritarian style of governance.

A second method used by authoritarian regimes is the deployment of slander and legal persecution aimed at “dishonoring” regime critics. Dishonoring serves to discredit those who act as a check on political power and authorities’ claims, from activists and journalists to judges and State Department officials. This too is a regularly-wielded tactic in American politics (e.g., during McCarthyism and the Vietnam War) that is being amplified under the current administration. President Trump’s unfounded accusation that protesters are paid professionals, for instance, portrays grassroots movements as duplicitous and casts them as illegitimate. His claim that the media is the primary “enemy of the American people,” in conjunction with assaults and the legal persecution of journalists, castigates the free press as criminal. Trump’s attacks against so-called “activist judges” and threats to punish disloyalty are also time-honored tactics used to discredit dissenters and instill fear in future whistleblowers. Such dishonoring renders the quotidian practice of free speech a subversive act, signifying an increase in the risks and costs of civic engagement and in simply doing one’s government job.

A third authoritarian style is the incitement of loyalist groups and thugs to enact repression on the regime’s behalf. This method is used quite effectively by state leaders the world over, including in the United States. Women of all ages, for example, have been increasingly subjected to anonymous rape and death threats for speaking out against President Trump. State-led incitement has also encouraged acts of hate against the Black Lives Matter movement, and according to the Southern Poverty Law Center and Human Rights Watch, vigilante violence and terrorist attacks against brown and black persons (including those perceived as Muslim) continue to rise. This mobilization helps powerholders by turning loyalists’ attention away from policies that come at their expense, such as the slashing of state benefits and protections. While such policies punish the very people leaders claim to defend (including poor and working-class white men, Trump’s largest group of supporters), loyalists are directed to scapegoat “negative others” for their troubles instead. The mobilization of loyalist and thug groups is also effective because this strategy enables authorities to deny responsibility for violence while simultaneously using extra-judicial attacks as an excuse for cracking down on dissenters in the name of law and order.

Negative othering, dishonoring, and loyalist counter-mobilization are only three examples of how democratically-elected leaders promulgate authoritarian styles of rule. This speaks to the need for researchers to draw further comparisons between the leadership styles of US authorities and autocrats in other regions. Authoritarian styles of governance are quite common across east and west, north and south. Considering that the United States shares its means of repression with many a dictatorship and collaborates with rights-abusers in Russia, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and elsewhere on matters of policy and war, this should not be surprising. All types of governments use the repression of historically-marginalized identity groups, women, the poor and working class, the free press, and dissenters in government to their advantage. As such, identifying common rights-suppressing styles will move us past unhelpful classificatory schemes that view democracy and authoritarianism as opposing ideal types. How authoritarian our political system is becoming is therefore not a zero-sum characteristic, but a question of degree.

I SAY IT IS THE MOON: TAMING THE AMERICAN POLITICAL WILL?

PETRUCHIO: I say it is the moon.

KATHARINA: I know it is the moon.

PETRUCHIO: Nay, then you lie: it is the blessed sun.

KATHARINA: Then, God be bless’d, it is the blessed sun: But sun it is not, when you say it is not; And the moon changes even as your mind. What you will have it named, even that it is; And so it shall be so for Katharina.

-Taming of the Shrew, William Shakespeare

In Shakespeare’s Taming of the Shrew, Petruchio denies his wife food and clothing and psychologically abuses her until she agrees to see the world as he declares it to be, showing us that “reality” can be manipulated. Petruchio also gives audiences a glimpse into the authoritarian aspiration to control the very perception and expression of reality. While authoritarian efforts don’t always succeed and dissent may still occur in different forms (e.g., Weeden Reference Wedeen1999), authoritarian states and leaders nonetheless make substantial investments toward owning and controlling media, suppressing information contrary to their interests, using repression to build quiescent and fearful populations, and sanctioning dissent that does emerge.

However, when Western repression scholars examine information environments, we typically don’t focus on these more fundamental reality contests. Studies of censorship (Earl Reference Earl2011) or state surveillance and control over information (e.g., Morozov Reference Morozov2011) are more common, highlighting information access dynamics. This emphasis risks misunderstanding or failing to deeply appreciate the potential impacts of contemporary political events; potential tectonic shifts in how “reality” is constructed (and by whom) are more important today than a narrow focus on information access and are only evident when one looks at the wider picture.

In 2017, Americans have seen physical attacks on journalists, which some see as “deserved” (Grynbaum Reference Grynbaum2017), and rhetorical attacks, as President Trump refers to unfavorable news reporting as fake news and decries media as the “enemy of the American people.” At least one foreign country has allegedly arrested or disappeared individuals looking into Trump-related businesses (Kinetz Reference Kinetz2017). A slowly simmering attack on climate science has, when combined with proposed radical government defunding of science, boiled to the point where scientists have marched to defend science. Substantial misinformation has been spread online, both by real actors and bots (Howard Reference Howard2017). A number of state-level bills limiting protest have been proposed.

But, this way of looking at these trends—as narrowly about information access—misses a far more fundamental and consequential dynamic: a war on facts, science, and journalism, misinformation, and false statements by public officials are not just about access to information, they are about the power to name and control the perception of reality.

From an information access point of view, each of these is troubling. Journalists are critical to collecting and distributing information, making physical and rhetorical attacks against them serious. Restricting data that can be collected and analyzed, removing public access to data, and failing to support or fund new data collection also impact information access. Misinformation muddies the waters, making it harder to consume accurate information or trust available information. Limiting protest or suppressing votes manufactures a false appearance of consensus.

But, this way of looking at these trends—as narrowly about information access—misses a far more fundamental and consequential dynamic: a war on facts, science, and journalism, misinformation, and false statements by public officials are not just about access to information, they are about the power to name and control the perception of reality. Gessen, a dissident Russian journalist, for instance, notes that we misunderstand what Putin and Trump share when they make verifiably false statements:

“Lying is the message. It’s not just that both Putin and Trump lie, it is that they lie in the same way and for the same purpose: blatantly, to assert power over truth itself… when he [Trump] claims that he didn’t make statements that he is on record as making, or when he claims that millions of people voting illegally cost him the popular vote, he is not making easily disprovable factual claims: he is claiming control over reality itself” (emphasis in original; Gessen Reference Gessen2016).

Democratic journalists and scholars think the question is narrow—about a specific claim, but Gessen is arguing that students of democracy need to focus on a thread that binds these acts together. Control over reality is a fundamental lever of power, which even today is wielded to control citizens in countries from North Korea to Russia (Pomerantsev Reference Pomerantsev2015).

To be sure, I am not arguing that President Trump or other US actors are attempting to gain authoritarian control over the US government or even that the political events I bring together are co-occurring by design. But, I am arguing that there are fundamental shifts in the information environment and in how Americans think and talk about facts and reality to which scholars studying repression, and democracy, need to pay much closer attention because they make erosions of democratic institutions more possible. Further, I am arguing that attending to these occurrences by thinking about them as narrowly about access to information, as opposed to a more fundamental play on who controls the perception and expression of reality, misses key theoretical and practical implications. Scholars also need to more heavily invest in studying the protection of first amendment rights, which protect journalists’ and scientists’ ability to anchor reality in facts, and protesters’ ability to challenge frames and assertions, not just because they preserve access to information, but because they forestall the power to control reality.

A PRESIDENT PRINCIPAL AND IMMIGRATION AGENTS: A MORAL HAZARD

In February 2017, as part of a generally nationalist set of policies on refugees and immigrants, the US Department of Homeland Security (DHS) made the deportation of all undocumented immigrants a priority, ordered the hiring of 15,000 immigration agents, and broadened their discretion to reach that goal. These policies carry out President Trump’s Executive Order 13767. The goal of these (and many other) policies initiated early in President Trump’s tenure has been consistent: to remove and prevent entry of as many immigrants as possible. Yet the methods to achieve that goal have been largely left to immigration agents to determine. This delegation process, common in politics, makes human rights abuses a very likely outcome with little recourse for victims.

Scholarship on political violence shows that a principal-agent relationship between governments and those who carry out orders often leads to violence or rights violations.

In standard principal-agent models, a principal values some output or result and delegates the task to an agent. The agent also values the output, being under contract for wages for success or punishment for failure to produce the result. But the desire for professional rewards differs from the principal’s value for the output itself. The agent prefers to reach those goals efficiently—with minimal effort—and often has less concern for the quality of the results than the principal. Having autonomy to carry out the task, the agent has incentives to reach the principal’s goals in the most efficient way possible, including cutting corners and other forms of shirking.

Scholarship on political violence shows that a principal-agent relationship between governments and those who carry out orders often leads to violence or rights violations. Officials order forces to control territory using any means, which includes violence against civilians unless otherwise prevented (DeMeritt Reference DeMeritt2015). Military and police torture to obtain information about terrorist or criminal activities, whether truthful or not. Torture is viewed as such an efficient means of achieving outcomes that it is the status quo tactic for agents of many types, requiring active efforts from any state that prefers to prevent it (Conrad and Moore Reference Conrad and Moore2010). Agents violate civil and physical rights to produce the state’s desired results, whether or not leaders specify a preference for abuse. Footnote 1

President Trump has made clear his willingness to devote a great deal of resources to expelling immigrants from the United States and keeping new ones out (e.g., proposals to build a wall, refugee bans, reduced migrant quotas). Agents have been ordered to find, arrest, and deport all of the estimated 11 million undocumented immigrants from the United States. The orders broaden agents’ discretion and powers far beyond what was allowed under the Obama administration. Agents under the prior administration prioritized undocumented immigrants who had committed serious crimes, but under the current discretion, agents are authorized to deport immigrants suspected of even minor scrapes, including traffic violations, without conviction (Ford Reference Ford2017).

The pressure to perform combined with wide discretion sets the stage for violations, and adverse selection makes them even more likely. When hiring agents, their type—diligent or reckless, pacific or aggressive, preferences for protection or violation—is unknown. While DHS may want skilled agents to protect immigrants’ rights, they cannot know for certain from one’s resume whether an agent has the skill and preferences to do that. To the extent that persons applying for employment as immigration agents have pre-existing negative beliefs or experiences with immigrants, the selection process is likely biased against human rights protections.

This is a recipe for human rights violations that have already come to fruition. Border and customs agents are not bound to constitutional rights protections in the way domestic police are, leading to violations of privacy, search and seizure laws, and habeus corpus provisions. Immigration agents use deception to gain entry into homes without warrants with increasing frequency. Immigrants are accused of crimes and deported without the chance to defend themselves in court. People are detained without charge or access to lawyers before being deported. Long-time residents are denied the right to a family, separated from spouses and children who are legal citizens of the United States. Violations have increased in large numbers during the early months of President Trump’s tenure. Though no reports are yet available for 2017, immigration agents are frequently accused of torturing persons in detention (Conrad, Haglund, and Moore Reference Conrad, Haglund and Moore2014), and this pattern is likely to continue under the president’s broad policies.

The rights of all persons, regardless of citizenship or documentation, should be respected as provided in the US Constitution and international law. The Trump administration’s strong mandates for mass deportation, combined with broad agent discretion and the likely selection of adversarial types of agents, create the ideal conditions for violations of civil and physical rights violations.

If the Trump administration intends to deport all undocumented migrants, careful attention to the principal-agent problem and the ways other organizations solve it can prevent violations of migrants’ rights. Lighten the pressure for immediate performance, carefully screen potential hires with an eye to de-escalation and values for persons regardless of group identity, train agents in rights protection, and develop incentives for agents to adhere to those protections in the practice of their duties. Human rights oversight bodies and NGOs can monitor and report violations if the administration will not (Welch Reference Welch2017). Changes such as these prioritize rights over production.

ACTIVISM IN AN AGE OF MASS SURVEILLANCE

Activism in an age of mass surveillance necessitates limiting organizers’ exposure and providing cover for mobilization. This essay illustrates these challenges by describing how one of the era’s most distinctive movements—Occupy Wall Street—successfully outpaced government surveillance during its earliest phases. Building upon the case material, I sketch several counter-balancing mechanisms enabling challengers to disrupt mass surveillance and/or governments to target would-be activists. Social movement scholars and practitioners can expand upon these ideas to predict the success or failure of future challengers.

Occupy Wall Street has become a symbol of a uniquely twenty-first century form of activism, which combines digital communication with disruptive, nonviolent direct action. There is, however, a surprising anachronism in “Occupy.” The movement sustained its preliminary mobilization using technologies and organizational forms developed decades earlier. Three months before the occupation of Zuccotti Park, Kalle Lasn (one of Occupy’s founders) flew from Canada to Brooklyn. In the basement of a brownstone, he and other organizers pored over maps, developed symbols and language to unite the movement, and planned strategies for coordinating with like-minded movements through offline, hub-and-spoke diffusion. Up until the day of occupation, the planning committee maintained a variety of printed maps identifying false “potential occupation zones,” designed to throw off authorities monitoring their activities (Schwartz Reference Schwartz2011).

Occupy Wall Street has become a symbol of a uniquely twenty-first century form of activism, which combines digital communication with disruptive, nonviolent direct action.

The movement’s willingness to substitute readily surveilled online activity in favor of more clandestine mobilization reveals the potential confines of information and communications technologies (ICTs). Research shows how ICTs reduce barriers to collective action both by lowering private costs and by increasing collective benefits (e.g., Little Reference Little2016; Masoulf Reference Mausolf2017). Of course, it is also the case that ICTs help governments to restrain the actions and impact of activists. Important research is now examining the limits of digital mobilization and, in particular, the ways in which governments restrict access and surveil usage to manage contentious politics (e.g., Lynch Reference Lynch2011; King et al. Reference King, Pan and Roberts2013; Lorentzen Reference Lorentzen2014).

Occupy’s tactical adaptation exemplifies several mechanisms activists can use to mobilize in an age of mass surveillance. Here, I illustrate two: concealment and obfuscation. Concealment involves tactics to cloak identifying information, such as the use unpredictable meeting locations or encrypted messaging services. Obfuscation involves, “the deliberate addition of ambiguous, confusing, or misleading information to interfere with surveillance” (Brunton and Nissnbaum Reference Brunton and Nissenbaum2015). Examples include the development of digital clones and randomly swapping identifying information (e.g., cell phone sim cards) as well as Occupy’s deceptive maps. Concealment and obfuscation each come with accompanying costs: when they succeed, they can limit the reach of activists’ communication. When they fail, they provide new information to surveillance institutions.

Simultaneously, governments retain at least two counter-strategies: disruption and screening. Disruption involves restricting activists’ communication with one another. A principal limitation with disruption is that, like concealment, disruption often reduces surveillance as well (Gohdes Reference Gohdes2015). Screening works in reverse, providing activists with incentives to reveal themselves. To illustrate, at the height of Occupy Wall Street, a false rumor spread through social media that Thom Yorke of Radiohead would play in Zuccotti Park. The influx of newcomers provided security forces monitoring social media, metadata networks, and CCTV with clear information on who was most likely to be mobilized next.

The history of social movements shows that form follows function—the agility and content of activism reflects institutionalized power. Centralizing governance draws activists to the capital; violent repression drives them underground (Tarrow Reference Tarrow2011; Tilly Reference Tilly2015). Likewise, contentious politics in an age of mass surveillance requires activists adapt to an environment in which governments possess unprecedented access to personal information and interpersonal communication. Activists need to develop new methods of concealment and obfuscation as authorities race to maintain an informational advantage.