Public opinion tends to be stable. Once formed, attitudes are persistent and endure over time at both the individual and the aggregate levels. Attitudes toward marriage equality are a notable exception. In 1988, only 11% of the US public supported the legalization of same-sex marriage; by 1996, that support had increased to 27% and, by 2006, to 35%. By 2013, polls showed that a majority of Americans supported marriage equality, and the latest polls put national support near the 60% mark. However, identity groups have changed their opinions at different rates (Public Religion 2014). To better understand these attitudinal shifts, this article explores how individual-level identities affect attitudes toward Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) rights.

Several theories regarding public-opinion change may explain this rapid opinion shift. Allport’s (Reference Allport1954) contact theory suggested that personal contact with LGBT individuals should prompt people to reconsider previously held prejudices. More Americans today are aware that they have personal contact with a member of the LGBT community (Public Religion 2014). Other theories point to cohort replacement, secularization, and a broader cultural shift (Banauch Reference Banauch2012).

We argue that when individuals realize that a member of one of their in-groups communicates support for LGBT rights, their own support increases. This occurs regardless of an individual’s sexual orientation and/or gender identity, even if that in-group is based on an unrelated identity (e.g., support for a professional sport or a sports team). In other words, a primed in-group identity (even if unrelated to being LGBT) should increase support for LGBT rights, provided that the shared identity is sufficiently strong.

Previous research generated three relevant models that outline the conditions under which individuals may undergo preference or attitude changes: Zaller’s (Reference Zaller1992) Receive-Accept-Sample model; Sherif, Sherif, and Nebergall’s (Reference Sherif, Sherif and Nebergall1965) Social Judgment Theory; and Petty and Cacioppo’s (Reference Petty and Cacioppo1986) Elaboration Likelihood Model. These three models indicate that the first step in successful attitude change is a willingness to receive, listen to, and process new information. By emphasizing a common identity, senders of communication establish themselves as a member of the receiver’s in-group; therefore, openness to listening should be increased.

It is well established that references to some identities can change public opinion. For example, partisanship can generate attitudinal change on noncontroversial, nonsalient issues (Carsey and Layman Reference Carsey and Layman2006; Lenz Reference Lenz2009) or when the partisan cue provides unexpected counter-stereotypical information (Bergan Reference Bergan2012). Lau and Redlawsk (Reference Lau and Redlawsk2006) found that many citizens use elite cues as a shortcut to understanding politics. This article extends that scholarship to argue that cues from members or elites in sports-fan in-groups also can motivate attitudinal change, even on an issue unrelated to sports.

The studies described in this article focus on football fans, who we believe to be more likely to support marriage equality if they see that football players or other fans are supporters. Loyalty to a sports team is an intense in-group membership for many Americans, whether the team is their college alma mater, from their hometown, or simply one with which they feel a connection. Football fans spend significant time and money on tickets, travel, and official insignia to show their loyalty and to watch and cheer for their team of choice. Identification with a sports team is enduring and often strong (Cottingham Reference Cottingham2012; Wann and Branscombe Reference Wann and Branscombe1993; Wann and Schrader Reference Wann and Schrader1996). Sports fans categorize themselves and others as in-groups and out-groups (Voci Reference Voci2006), and they exhibit typical in-group favoring behaviors, including rating other in-group members more favorably than out-group members (Wann and Branscombe Reference Wann and Branscombe1995; Wann and Dolan Reference Wann and Dolan1994). Shared identity as a fan of a team also can lead to increased prosocial behavior (Platow et al. Reference Platow, Durante, Williams, Garrett, Walshe, Cincotta, Lianos and Barutchu1999).

Perhaps taking their cue from this concept, marriage-equality organizations are conducting ongoing campaigns that tap into sports-fan in-group identities to shift attitudes about gay rights.

Perhaps taking their cue from this concept, marriage-equality organizations are conducting ongoing campaigns that tap into sports-fan in-group identities to shift attitudes about gay rights. Most well known among these organizations is Athlete Ally, founded in January 2011 by Columbia University wrestling coach Hudson Taylor. A significant portion of the organization’s work involves encouraging straight athletes to publicly endorse equality and respect for LGBT athletes. As Taylor noted in a Huffington Post piece on January 29, 2013, “Fans take cues from professional athletes” (Taylor Reference Taylor2013).

Sports leagues in the United States have a long tradition of intolerance for gay and lesbian athletes, especially in the major leagues including the National Football League (NFL), and the tradition filters down to sports fans. Homosexuality among men is assumed to be accompanied by feminine stereotypes (e.g., “little” and “soft”); typically, gay athletes in major sports such as football, basketball, and hockey have stayed closeted to avoid calling their masculinity, and by association their athletic ability, into question. In the sports world, “traditional masculine traits thrive and are preserved” (Gregory Reference Gregory2004, 267) and “challenges to the status quo of heteronormativity in sport are met with resistance and retaliation” (Williams Reference Williams2007, 255). Given this dynamic among many sports fans, particularly in the hypermasculine sports of the top leagues, statements of support by professional football players or fans for marriage equality or other LGBT rights will be received by most people as unexpected—as a cognitive “speed bump.” Scholarship on persuasion and priming suggests that this makes those statements particularly powerful (Bergan Reference Bergan2012; Bettencourt et al. 2015).

Using different samples (i.e., students, online samples, and people on the street), we conducted three randomized survey experiments—two coinciding with related real-world events—to test the power of priming a shared identity as a fan of professional football to generate attitudinal change on LGBT rights. Two experiments were conducted via online surveys (i.e., Mechanical Turk/Qualtrics and Google Consumer Surveys); the third was conducted via face-to-face interactions. In each scenario, we targeted football fans (or fans of a particular team) as well as non-fans, exposing both groups to identical statements of support for certain LGBT rights attributed to either a prominent sports figure or an anonymous individual. In each sample, we found that support for same-sex marriage increased dramatically among fans that were exposed to messages attributed to members of their football in-group. Among non-fans, the different messages did not generate any measurable differences in attitudes.

EXPERIMENT #1: FOOTBALL FANS AND ATHLETE ALLIES

There is little tolerance for openly gay players in the NFL; however, in recent years, some NFL players have voiced support for gay rights, including former Minnesota Vikings punter Chris Kluwe and Baltimore Ravens linebacker Brendon Ayanbadejo. In 2013, the Ravens were matched against the San Francisco 49ers in the Super Bowl. Ayanbadejo’s outspoken support for same-sex marriage and his increased visibility in the weeks leading up to the Super Bowl provided an opportunity to test our theory that football fans would be more supportive of marriage equality when they were informed of his support.

The experiment was conducted across multiple locations: a small private college in California, a large public university in Texas, and online with the US Internet population. Students at the two institutions were emailed invitations to participate in a survey in exchange for a chance to win a $100 Amazon gift card. In addition, participants from across the United States were recruited using Mechanical Turk (MTurk); they received $0.50 for their completed responses. Overall, 426 participants completed the survey, including 115 California students, 99 Texas students, and 212 MTurk workers.

After opening the invitation and providing informed consent, participants were given a false choice that “assigned” them to a public-policy issue. This was done to limit social-desirability bias and to convince participants that there was more than one issue being investigated. They were then randomly assigned to read a paragraph about either same-sex marriage with supportive quotations—with or without attribution to professional athletes—or a placebo paragraph about recycling. For the marriage-equality treatment groups, participants first read the following opening paragraph that introduced the topic:

Americans fundamentally disagree on many core political issues. One of the issues where people disagree is whether gay and lesbian Americans should be able to marry. Many individuals have endorsed gay marriage while many others are opposed.

The online text then varied depending on whether the participant had been randomly assigned to the control group or the treatment group. The treatment group read the following paragraph:

Brendon Ayanbadejo, All-Pro Linebacker for the Baltimore Ravens in the National Football League, supports gay marriage. He recently said, “Right now it’s the time for gay rights and it’s time for them to be treated equally and for everybody to be treated fairly, in the name of love.” Chris Kluwe, punter for the Minnesota Vikings and another supporter, recently wrote that same-sex marriage would make gays “full-fledged American citizens just like everyone else, with the freedom to pursue happiness and all that entails.” Sean Avery, forward for the New York Rangers NHL team, recently said, “I’m a New Yorker for marriage equality. I treat everyone the way I expect to be treated and that applies to marriage. Committed couples should be able to marry the person they love.”

In contrast, participants who were randomly assigned to the control group read a paragraph with the same supportive quotations attributed to anonymous citizens. They then answered two questions about their own attitudes, including how they would vote on a hypothetical state-ballot initiative on same-sex marriage. Participants also rated their level of interest in sports and answered demographic questions including age, gender, and partisanship.

As shown in figure 1, respondents who read the Professional Athletes paragraph were most supportive of marriage equality compared to the placebo; support increased by more than 10 and more than 8 percentage points among Sports Fans and Non–Sports Fans, respectively. The former is statistically significant, which confirms our hypothesis. Footnote 1

We found the highest overall support for marriage equality and the highest percentage of respondents reporting that they would vote in favor of a hypothetical ballot initiative in the Professional Athletes condition (see tables 1A and 2A in the appendix). We then divided the sample based on three measures of sports identity and behavior: (1) expressed identity as a sports fan; (2) frequency of choosing sports-related coverage (compared to other forms of entertainment); and (3) frequency of watching sports-related events. We used those responses to generate a Sports Fan index. As shown in figure 1, respondents who read the Professional Athletes paragraph were most supportive of marriage equality compared to the placebo; support increased by more than 10 and more than 8 percentage points among Sports Fans and Non–Sports Fans, respectively. The former is statistically significant, which confirms our hypothesis. Footnote 1 As shown in figure 2, support for the hypothetical ballot measure increased even more dramatically among Sports Fans, from 49% in the placebo condition to almost 65% in the Professional Athletes condition–a statistically significant increase of 15.7 percentage points. Support also increased among non–Sports Fans but the differences were not statistically significant.

Figure 1 Support for Marriage Equality, Super Bowl Experiment

Figure 2 Support for Hypothetical Ballot Measure on Marriage Equality, Super Bowl Experiment

EXPERIMENT #2: AND THEN MICHAEL SAM CAME OUT

In February 2014, Michael Sam, a defensive end from the University of Missouri, came out as gay before the NFL draft. Reaction from NFL leaders and fans was swift and divided, including a flurry of homophobic tweets and a story in Sports Illustrated that quoted negative reactions from anonymous NFL coaches and executives. Other observers noted that what mattered was only Sam’s abilities on the field, not his sexual orientation. The NFL issued an official statement of support, noting that the league had adopted a sexual-orientation antidiscrimination and harassment policy in April 2013. NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell also spoke out personally in support of Sam, stating:

He’s proud of who he is and had the courage to say it. Now he wants to play football. We have a policy prohibiting discrimination based on sexual orientation. We will have further training and make sure that everyone understands our commitment. We truly believe in diversity and this is an opportunity to demonstrate it.

In the midst of this controversy, we tested the effect of Goodell’s statements about inclusion and antidiscrimination on the openness of football fans to support LGBT rights. This experiment was conducted using Google Consumer Surveys. A screening question selected either football fans or individuals with no interest in professional football. The question read: “On a scale of one to five, how interested are you in professional football?” Those asked this question chose from five possible responses ranging from “not at all interested” to “extremely interested,” with the order of the responses randomly reversed. Only those individuals responding “not at all interested” or “extremely interested” were selected for the second question; others were not included in the experiment. The second question randomly exposed participants to one of two quotations. The treatment quotation read as follows:

NFL’s Roger Goodell recently said discrimination based on sexual orientation is inconsistent with NFL values. Do you agree?

The control quotation read as follows:

A corporate leader recently said discrimination based on sexual orientation is inconsistent with modern values. Do you agree?

The five possible responses, displayed in randomly reversed order, were “strongly agree,” “somewhat agree,” “neither agree nor disagree,” “somewhat disagree,” and “strongly disagree.” Although the quotations did not directly reference Sam, any serious football fan would have been aware of the ongoing discussion. Sam’s photograph was featured on the cover of the issue of Sports Illustrated that hit newsstands the week before our experiment began and his decision to come out was the topic of thousands of news stories.

The experiment was in the field February 18–20, 2014. A total of 811 responses were collected, including 409 individuals who were “extremely interested” in professional football and 402 who were “not interested at all.”

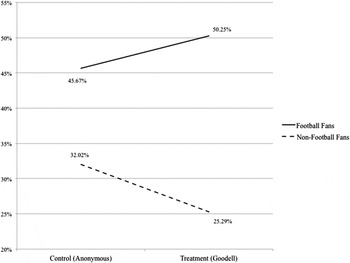

As shown in figure 3, football fans exposed to the Goodell prompt were twice as likely to report that they supported the statement of nondiscrimination as were non-fans, a difference of 25 percentage points. Put simply, priming fans’ identity as football fans led to increased support for nondiscrimination. Footnote 2

Figure 3 Support for Nondiscrimination Statement, Michael Sam/Roger Goodell Experiment

EXPERIMENT #3: PACKERLAND

The third experiment focused on a specific team: the Green Bay Packers. In the fall of 2014, we conducted a randomized survey experiment on the sidewalks of Appleton, Wisconsin. In exchange for a Starbucks or Dunkin’ Donuts gift card, respondents completed a paper survey about their interest in professional sports, support for the Green Bay Packers, attitudes about same-sex marriage, and various demographic variables. Half of the respondents were shown a photograph and read a statement that noted the support for marriage equality by Green Bay Packers Hall of Famer LeRoy Butler; the other half read and saw parallel information from entertainer Jay-Z. We hypothesized that the in-group elite cue (i.e., Butler) would increase support for marriage equality and LGBT rights among Packers fans but not among non-fans. Data were collected by undergraduate students recruited through the career-services office of the local college, Lawrence University. The survey began by asking questions to measure the degree to which respondents were fans of sports in general, the NFL, and the Green Bay Packers. They were then shown a photograph of either Butler or Jay-Z, with the following prompt:

[Green Bay Packers Hall of Famer LeRoy Butler / Rapper and music producer Jay-Z] (seen in the photo on the left) supports same-sex marriage. What do you think? Should gays and lesbian individuals (check one):

-

◦ be able to get married

-

◦ be able to enter into a legal partnership similar to but not called marriage (such as a domestic partnership or civil union)

-

◦ have no legal recognition given to their relationships

Additional survey questions collected demographic information including age, gender, race, homeownership (as a proxy for income), and partisanship. A total of 306 surveys were collected from October 19 to November 12, 2014, including 156 with the Butler prime and 150 with the Jay-Z prime.

We separated respondents into two groups based on their response to the question: “Thinking specifically now about the Green Bay Packers, which of the following best describes how you feel about the team?” Possible responses included “I’m a huge fan,” “I’m somewhat of a fan,” “I’m not much of a fan,” and “I’m not at all a fan.” We coded respondents who gave one of the first two responses as Packers fans and those who gave one of the two latter responses as non-Packers fans. As predicted by our hypotheses, the difference in levels of support for marriage equality among non-Packers fans was not affected by the treatment (i.e., exposure to the Butler photograph and prime). Among Packers fans, however, exposure to the treatment increased support by more than 14 percentage points, as shown in figure 4. This difference is statistically significant. Footnote 3

Primed with that sports-fan identity and presented with an unexpected cue of support for marriage equality, fans are motivated to reconsider their attitude on the issue—and, potentially, even change their opinion—to confirm or normalize their in-group membership.

Figure 4 Support for Marriage Equality, Green Bay Packers Experiment

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

The world of professional sports and the NFL in particular is overwhelmingly one of heteronormativity and resistance to gay rights. Support for same-sex marriage equality from NFL elites thus constitutes a cognitive “speed bump” for people who strongly identify as fans. Primed with that sports-fan identity and presented with an unexpected cue of support for marriage equality, fans are motivated to reconsider their attitude on the issue—and, potentially, even change their opinion—to confirm or normalize their in-group membership.

Across three survey experiments, we consistently found that football fans assigned to a treatment group that primed a sports-fan identity and provided a cue of support for LGBT rights were more supportive of those rights compared to fans assigned to a control group. Among non-fans, in contrast, exposure to the same cues produced negligible differences in attitudes. Because non-fans do not consider themselves part of the in-group of football fans, the cueing of football-fan identity did not make those treatment conditions more compelling or constitute as notable a cognitive speed bump. Our findings suggest that in-group elite cues showing support for LGBT rights may give social permission to those who otherwise may believe that their opinion is an isolated one. In these experiments, we found empirical support for the claim from Athlete Ally’s Hudson Taylor: “Fans take cues from professional athletes.”

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1049096516001359.Footnote *

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Calvin Husmann at Lawrence University for facilitating the Wisconsin experiment and Lawrence students Emma Huston, Logan Beskoon, Amalya Lewin-Larin, Anastasia Skliarova, Yuchen Wang, and Manny Leyva for data collection. All experiments were approved by the Menlo College Institutional Review Board. Our thanks to Paul Gronke and the anonymous reviewers of PS: Political Science & Politics for their helpful suggestions; all errors, of course, remain our own. Earlier versions of this article were presented at the 2015 Annual Meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association and the 2014 Annual Meeting of the Western Political Science Association.