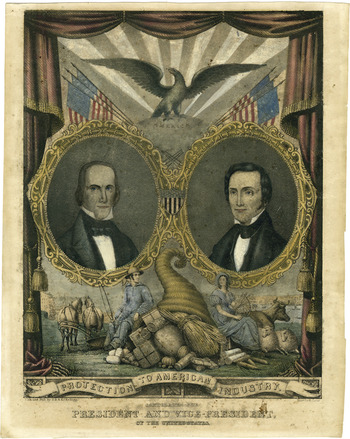

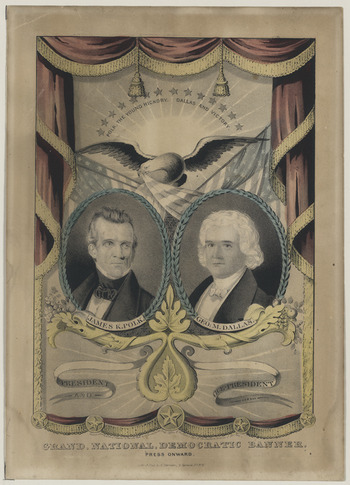

Historically the ephemeral hardworking American political poster has been sorely neglected for the last one and seventy years despite its effectiveness in conveying a political message to millions of voters, often through the skillful use of visual communication. From its humble beginnings in the 1840s, the great American political campaign poster has been ever tied to technological innovation. The new lithographic printing process, largely developed in Germany, was becoming widespread at the same time that Andrew Jackson and his fellow Democrats expanded the voting franchise to nearly all white males. This dramatic increase in the number of voters immediately created a huge new market for printed campaign material as candidates scurried to enlist new voters and build party identity. In response, firms producing cheap hand-colored prints on a variety of subjects that were in great demand begin issuing prints of the presidential and vice-presidential candidates. The first appeared in the 1844 campaign between Whig Party candidates Henry Clay and Theodore Frelinghuysen and the winning team of James K. Polk and George M. Dallas (see figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1 1844 Whig candidates Henry Clay and Theodore Frelinghuysen

Source: Kellogg Brothers Print, Courtesy of The Connecticut Historical Society.

Figure 2 1844 Democrats James K. Polk and George M. Dallas

Source: Grand National, Democratic banner. (James K. Polk and George M. Dallas). Lithograph N. Currier, 1844. Library of Congress, Reproduction Number: LG-DIG-ppmsca-07682 (digital file from original print).

The hand-coloring that made possible these prints was usually done by women. Currier and Ives employed over a dozen who painted only one color—a form of assembly line art. The company issued jugate portraits of presidential candidates from 1844–1880 in a series titled Grand National Banners. Rival Kellogg Brothers of Hartford, Connecticut followed suit with portraits of the quadrennial candidates until at least 1864. From 1844 on, the hand-colored visual appealing lithographic campaign poster competed with the popular letterpress broadside and with engraving but the hand-colored print became an essential feature of future campaigns. Two or three color prints could be done by letterpress and color prints were possible through chromolithography although the complicated process required individual stones or plates for each color and was time consuming and expensive. Chromolithographic political campaign posters were occasionally printed but the process was more frequently used to print circus and show posters.

Whether or not these standard campaign jugate posters were ordered in quantity by national campaign headquarters, by local campaign committees, or largely by individuals remains an open question. But it was the cheaper hand-colored print that birthed the great American political campaign poster. Graphic art had been democratized through lithography, now widely available to all. These early printmakers, long before Marshall McLuhan understood that the “medium is the message (1964)” had set in motion a means of conveying political messages simply and directly; a style of communication that would balloon exponentially in the coming age of mass man. Ironically, the great American political poster, while often elaborately designed and beautifully printed, remains utilitarian and ephemeral. Often exposed to the elements or simply discarded, the poster leads a perilous existence.

Kellogg Brothers’ campaign prints are seen far less often than those of Currier and Ives though they sometimes possess a far richer iconography. The 1844 hand-colored print for Clay and Frelinghuysen is an outstanding example (see figure 1). The nineteenth century poster visually communicated through an iconography that began with the founding of the Republic and was widely understood. While the literacy rate in the United States was quite high, the visual language employed by poster designers was a surer means of conveying a campaign’s message—an effort to bypass the rational thought process in an effort to induce an emotional response. Common features of this American patriotic iconography (democratic forms) included the bald eagle, wings spread and clutching thirteen arrows in one claw, that symbolized the union of the original states and in the other claw an olive branch. The flag and or the shield of the union, along with the liberal use of laurel wreaths, drapery, bunting, banners and slogans surrounded the portraits of the candidates. The repeated use of the rays of the sun connoted the brilliance of the aspirants and a glorious future for the republic under their leadership, while oak leaf motifs suggested strength, courage and endurance.

These early printmakers, long before Marshall McLuhan understood that the “medium is the message” had set in motion a means of conveying political messages simply and directly; a style of communication that would balloon exponentially in the coming age of mass man.

Often campaign posters, like that of the 1848 Free Soil Party, were adorned with an image of Columbia (Lady Liberty) holding a spear topped by a Phrygian cap, headgear worn by free citizens in Republican Rome, and standing guard in the Temple of Liberty (see figure 3). The early Republic’s fascination with symbols from antiquity, especially from the Greeks and Romans, was ubiquitous and spurred on by American romanticism, sometimes to the extent that statesmen were portrayed dressed in Roman togas. The prints proclaimed that the political dreams of Plato and Aristotle, in spite of serious political disputes and deep divisions, would be realized by the ambitious young nation, a city on the hill with a seemingly unlimited future.

Figure 3 1848 Free Soil Party, Martin Van Buren and Charles F. Adams

Source: Grand Democratic Free Soil banner. (Martin Van Buren & Charles F. Adams). Lithograph by N. Currier, 1848. Library of Congress, Reproduction Number: LCUSZC2-2465 (color film copy slide).

To establish fitness for office, candidates often claimed that they were in the tradition of past successful presidents—especially the founding fathers. The 1852 Whig Party candidates Winfield Scott and William Graham, for example, claimed political lineage to George Washington and the Currier and Ives campaign print included a portrait of the first president and one of Daniel Webster, an effort to boost electoral successful for a party badly divided (see figure 4). Regardless of Scott’s appeal to history and unity, the candidate was soundly beaten by the Democrat Franklin Pierce. James K. Polk in 1848 was dubbed “the Young Hickory” a reference to Andrew Jackson known as “Old Hickory.” To this day candiates attempt to elevate themselves into the pantheon of famous presidents—Washington, Jefferson, Jackson, Lincoln, the Roosevelts, Kennedy, and Reagan.

Figure 4 1852 Democratic Party candidates Winfield Scott and William Graham

Source: Grand, national, Whig banner. Published by N. Currier, c1852, lithograph, hand-colored. Library of Congress, Reproduction Number: LC-USZC2-2493 (color film copy side).

Slogans and catch phrases adorn these early campaign prints in an effort to convey a campaign’s central message in as few words as possible. Zachary Taylor in 1848 proclaimed “Protection to American Industry;” the first Republican ticket in 1856 deemed John C. Fremont and William L. Dayton “The Champions of Freedom;” and Abraham Lincoln in 1864 pushed “Liberty, Union and Victory” (see figures 5 and 6). Americans liked to think of their presidental candidates as being one of them and bestowed on them nicknames, not all complimentary, that satisfied their egalitarian needs: Lincoln, Honest Abe or the Railsplitter; Ulysses S. Grant, Unconditional Surrender Grant; James A. Garfield, Boatman Jim; Grover Cleveland, Uncle Jumbo; or Benjamin Harrison, the Human Iceberg.

Figure 5 1856 Republican Party candidates John C. Fremont and William L. Dayton

Source: The Champions of Freedom. John C. Fremont and William L. Dayton. Lithograph by Charles Grebner, 1856. Reproduction Number: LC-USZ62-7815.

Figure 6 1864 Republican Party nominees Abraham Lincoln and Andrew Johnson

Source: Grand National Union banner for 1864. (Abraham Lincoln and Andrew Johnson). Lithograph by Currier and Ives, 1864. Library of Congress, Reproduction Number: LC-DIG-ppmsca-17562 (digital file from original print).

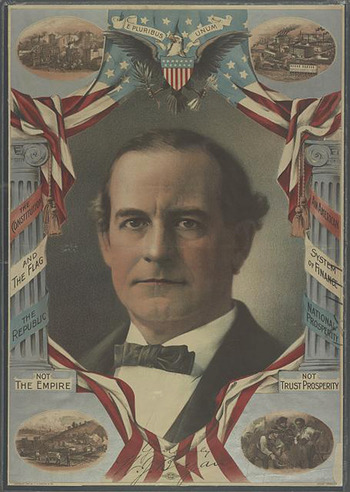

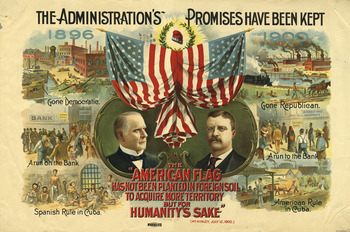

In the 1880s, technological advances in lithography made possible the cheap color print, a revolution that produced an explosion of color and a host of new companies. The age of the hand-colored print was over. Some of the best designed and most colorful political posters ever created grace the presidential campaigns of the era. Kurz and Allison, a Chicago company, printed spectacular prints for the 1888 Republican, Democratic and Union Labor Party candidates—Benjamin Harrison and Levi P. Morton, Grover Cleveland and Allen G. Thurman, and Anson J. Streeter and Charles E. Cunningham (see figure 7). A barrage of colorful posters surrounded the elections of 1896 and 1900, fierce contests that pitted Republican William McKinley against Democrat William Jennings Bryan (see figures 8 and 9). Americans of the era fell in love with color printing. Art prints and posters; advertising that included trade cards, baseball cards and circus and Wild West show posters; theater posters; and the colorful penny postcard took America by storm (see figure 10). Elaborate outdoor displays consisting of street banners hung in conjunction at various heights became popular with political campaigns and advertisers. The three largest circuses, Adam Forepaugh and Sells Brothers, Barnum and Bailey’s Greatest Show on Earth, and Ringling Brothers’ World’s Greatest Shows, ordered large color posters by the tens of thousands. Political campaigns were further enhanced when color was captured in the celluloid button that was invented and patented in 1896 by the Whitehead and Hoag Company of Newark, New Jersey. The campaign button or campaign pin swept the nation and political parties of all stripes placed huge orders. The new color posters, window cards, fliers, brochures, outdoor displays and elaborate rosettes often festooned with six inch color celluloid buttons became the mainstay of political campaigns and a bulwark of advertising.

Figure 7 1888 Democratic Party candidates Grover Cleveland and Allen G. Thurman

Source: Democratic nominees. For President, Grover Cleveland. For Vice President, A.G. Thurman. Lithograph by Kurz & Allison 1888. Library of Congrss, Reproduction Number: LC-DIG-pga-03403 (digital file from original print).

Figure 8 1896 Democratic Party nominee William Jennings Bryan

Source: The Constitution and the Flag. The Republic not the Empire. An American System of Finance. National Prosperity, not Trust Prosperity. No date. Library of Congress, Reproduction Number: LC-DIG-pga-04258 (digital file from original item). LC-USZ62-10479 (b&w film copy negative).

Figure 9 1900 Republican candidates William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt

Source: Courtesy of the Ohio History Connection.

Figure 10 1908 Postcard for Republican nominees William H. Taft and James S. Sherman

Source: Courtesy of author’s collection.

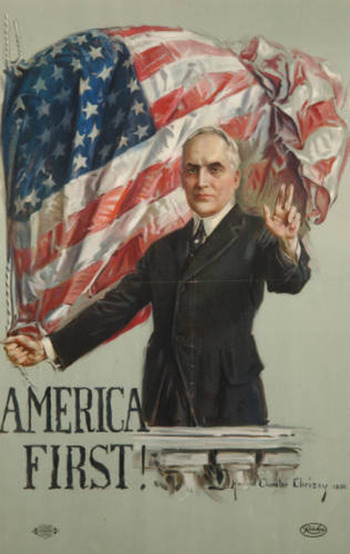

By 1907 Ira Rubel’s offset printing press was up and running, cranking out large quantities of cheap political posters using a photo-mechanical process that featured black and white or brown tone portraits of the candidates (see figure 11). The marvelous color lithographic print of the fin d’ siècle faded into obscurity. One of the great color lithographing companies, Strobridge, in Cincinnati, Ohio drastically cut production of this type of print in the years leading up to World War II. Strobridge printed huge outdoor circus, theater and show poster displays, the largest of which consisted of 1,562, one sheets, pasted to the side of Madison Square Garden. The 1900 William Jennings Bryan poster (see figure 12) is a Strobridge lithograph, though the company rarely printed campaign posters. In the elections of 1916 and 1920, the four-color offset printed posters were on display as demonstrated by the large Warren G. Harding poster by the famous illustrator Howard Chandler Christy who was known for his World War One Navy recruiting posters featuring beautiful modern stylized versions of Lady Liberty (see figure 13).

Figure 11 1920 Democratic candidate James Cox

Source: Courtesy of author’s collection.

Figure 12 1900 William Jennings Bryan

Source: The Issue –Liberty, Justice, Humanity. No Crown of Thorns, no Cross of Gold. Lithograph by Strobridge Lithographing Company, 1900. Library of Congress, Reproduction Number: LC-DIG-pga-02808.

Figure 13 1920 Republican Party nominee Warren G. Harding

Source: Poster by Howard Chandler Christy. Courtesy of the Ohio History Connection.

Unfortunately few offset color political posters of merit emerged until the 1940 campaign when the Hoosier Wendell Willkie unexpectedly captured the Republican presidential nomination and ran against the indomitable Franklin D. Roosevelt. James Montgomery Flagg’s retro use of his famous World War One “Uncle Sam” image that read “I Want You F.D.R., Stay and Finish the Job!” was one of the best of the 1940 posters (see figure 14). The Willkie campaign produced a series of fine posters titled “Work With Willkie” that pictured people from the working class, a female factory worker on one and a male worker on another, in an effort to gain votes in traditional Democratic blocs (see figures 15 and 16). Roosevelt, breaking the two-term tradition established by George Washington, went on to win the general election. From 1940 onward, the color offset poster dominated and enticing posters were designed that attempted to grab your attention and win your vote.

Figure 14 1940 Democratic Party nominee Franklin D. Roosevelt

Source: I Want You F.D.R.–Stay and Finish the Job! James Montgomery Flagg, c1944. Library of Congress, Reproduction Number: LC-DIG-ppmsca-12898 (digital file from original print) LC-USZC4-6613 (color film copy transparency).

Figure 15 1940 Republican Party candidate Wendell Willkie

Source: Courtesy of author’s collection.

Figure 16 1940 Republican nominee Wendell Willkie

Source: Courtesy of author’s collection.

Beginning with the election in 1940 and ending in the campaign in 1964, a new design emerged that became widely known as the “floating head” poster. These posters had a run of over twenty years and yet no historian has attributed this innovation to a particular designer. It is likely that the decision for this design was made by a printer and that when other printers and their customers saw these fun “floating heads” they rapidly caught on (see figure 17 and 18). The “floating heads” poster just as suddenly disappeared, much like the hula-hoop, trampoline centers, blue suede shoes, and the flat-top haircut. The prevailing international style of design favored by large advertising firms was challenged by new innovative styles pioneered by the civil rights and anti-war movements as well as by denizens of psychedelia in their revolt against the establishment. The boomers had arrived; the poster was back after serious decline since the end of World War II.

Figure 17 1952 Republican Party candidates Dwight Eisenhower and Richard M. Nixon

Source: Courtesy of author’s collection.

Figure 18 Democratic Party nominees John F. Kennedy and Lydon Johnson

Source: Courtesy of author’s collection.

In the rebellious 1960s, one of the most prolific periods in American poster making, a plethora of artists produced thousands of posters, hundreds of them unique eye-popping images in vibrant color, using new printing techniques in a wide range of styles. This exciting topsy-turvy period unleashed a poster explosion that began with the civil rights movement and flowed into a youth rebellion in which drugs, rock ‘n’ roll, opposition to the war in Vietnam, and politics were inseparable. The “peace candidate,” Senator Eugene McCarthy, failed to capture the ’68 Democratic Party nomination, but his supporters created outstanding political posters (see figure 19). Peace candidate Senator George McGovern received the Democratic Party nomination in 1972 and attempted to ride this decade-long wave of protest and change into the White House (see figure 20). The art community, including outsider artists, responded enthusiastically creating an avalanche of posters. Famous artists and illustrators joined the movement: Alexander Calder, Paul Davis, Mary Corita Kent, Larry Rivers and Andy Warhol. Supporters of Shirley Chisholm, the first black woman to seek the presidency, along with her campaign, created a number of fine posters (see figures 21 and 22). In this wheat paste era, hundreds of posters were made by grassroots supporters; many were first timers at poster making. Significantly, the limited edition screen print was brought into the political campaign in both ’68 and ’72, greatly enriching this fabulous era of the great American campaign poster. The screen print would show on occasion in future campaigns and then come to the fore in President Barack Obama’s run for the presidency in 2008.

Figure 19 1968 Democratic hopeful Eugene J. McCarthy

Source: Courtesy of author’s collection.

Figure 20 Women for McGovern

Source: Courtesy of author’s collection.

Figure 21 1972 Democratic Party hopeful Shirley Chisholm

Source: Poster by Ed Wong-Ligda and Robert Newman, Courtesy of author’s collection.

Figure 22 1972 Democratic Party hopeful Shirley Chisholm

Source: Poster by Mary Corita Kent. Courtesy of author’s collection.

With the crushing defeat of George McGovern, the country rejected the riotous sixties and moved back to the political center, a move that resulted in a great dearth of exciting posters. In campaign ’76, the art community activists did not cotton to a southern centrist like Jimmy Carter nor were they enthused by Ted Kennedy’s challenge of the sitting president. Carter quipped that he’d “whip his ass” and he did. Having snuffed out the Kennedy revolt, Carter prevailed and received the Democratic nomination. In the general election Carter was narrowly defeated by Ronald Reagan, a campaign that induced much excitement on the Right and a campaign that produced a number of quality posters (see figure 23). In 1984 the campaign poster underwent a mini-renaissance as Senator Gary Hart of Colorado, McGovern’s 1972 campaign manager, entered the primaries as did George McGovern, who decided to run in order to educate the electorate on what he perceived were the critical issues being ignored—US intervention in Nicaragua and El Salvador (see figure 24). In 1988, the Jesse Jackson campaign briefly breathed new life into the great American campaign poster with creations by Leonard Baskin (see figure 25) and artist Jack Hammer.

Figure 23 1980 Republican nominee Ronald Reagan

Source: Courtesy of author’s collection.

Figure 24 1984 Democratic hopeful Gary Hart

Source: Poster by Thomas W. Benton, Courtesy of author’s collection.

Figure 25 1988 Democratic hopeful Jesse Jackson

Source: Poster by Leonard Baskin, Courtesy of author’s collection.

Rock ‘n’ roll, not politics, pushed poster making forward in the ‘80s and 90s as it had psychedelic posters in the ‘60s. Hundreds of local and regional bands emerged that created a need for promotional material. With the death of LPs, this vacuum was filled by a host of young and talented graphic artists. To create quality posters and handbills in small runs these artists turned to screen prints and letterpress. Back in vogue, these printing methods proved ideal solutions—poster art moved in fresh and creative new directions. Letterpress operations across the nation that were on their last legs or that had long ago shut their doors were purchased and brought back to life. Young artists appreciated the printing process and recognized a chance to preserve the past. Hatch Show Print in Nashville was one of the first and has been followed by many successful operations in cities like Asheville, North Carolina; Kansas City, Missouri; Heber City, Utah; Portland, Oregon and Somerville, Massachusetts. Screen prints flourished as did the new computer generated inkjet prints and graffiti.

Pop artist Roy Lichtenstein, commissioned by the California Democratic Committee, created a poster for Michael Dukakis in 1988 and did so again for Bill Clinton in 1992 with a signed limited edition print and an open offset poster titled The Oval Office (see figure 26). Bill Clinton was featured at the Democratic National Convention in Madison Square Garden in 1992 (see figure 27) and the Republicans in 2004 brilliantly branded Bush by flooding the country with black posters and bumper stickers adorned with a silver W or Dubya (see figure 28).

Figure 26 1992 Democratic Party candidate William J. Clinton

Source: Print and poster by Roy Lichtenstein. Copyright Estate of Roy Lichtenstein. Courtesy of author’s collection.

Figure 27 1992 Democratic Convention, New York City

Source: Courtesy of author’s collection.

Figure 28 2004 Republican Party candidate George W. Bush

Source: Courtesy of author’s collection.

Senator Barack Obama unexpectedly won the Iowa caucuses and touched off a poster explosion, an unforgettable roller-coaster ride, only seen recently in 1968 and 1972. Street artists and anti-establishment artists decided to participate in the campaign, to drop in rather than drop out, and created dozens of exciting posters. Hollywood and rock stars turned out as well and produced a creative groundswell. For Obama supporters the dream was not dead and again fundamental change through the political process seemed possible. Many of the best campaign posters were the ones made unofficially and were a part of Obama gatherings and were reminiscent of Avalon and Fillmore Ballroom concerts and the ’68 McCarthy and ’72 McGovern happenings. Limited edition screen prints were created by artists like Robert Indiana, Shepard Fairey, Ray Noland, Ron English, Emek, Antar Dayal, and Billi Kid. The Kid used stencils and spray paint screen prints incorporated into outdoor installation—guerilla art actions—surrounded and bedizened with stickers (see figure 29). Ryan Red Corn, an Osage Indian from Pawhuska, Oklahoma and founder of Buffalo Nickel Creative, weighed in with the fine screen print “Native Vote 2008” in blue, red and yellow versions (see figure 30).

No campaign in American political history has been as graphically savvy, tightly controlled, and ultimately successful as was the 2008 Obama team.

Figure 29 2008 Democratic Party nominee Barack Obama

Source: Screen print by Billi Kid, Courtesy of Billi Kid.

Figure 30 2008 Obama screen print

Source: Screen print by Ryan Red Corn, Courtesy of Ryan Red Corn.

These outsider, hip-hop, skateboarder, guerilla artists brought not only their talent but a host of newfangled communication devices into the mix—e-mail, the cell phone, video cameras, websites, iPods, YouTube, Facebook, Myspace, Twitter, Instagram, podcasts, and webisodes. The changes that occurred in the 1980s, the return of letterpress, screen prints and pioneering work with the fast developing inkjet print (giclée), now combined with the new technology revolution to produce hundreds of posters that were photographed with cellphones and dispatched around the world in seconds.

No campaign in American political history has been as graphically savvy, tightly controlled, and ultimately successful as was the 2008 Obama team. The campaign jumped on the art bandwagon with a series of ten screen prints that started with Shepard Fairey, who created the iconic Hope poster, but Chicago artist Ray Noland actually got the ball rolling with a series of screen prints that he stealthily plastered around Chicago late at night. A few outsider artists were carefully brought inside by the Obama campaign and moved into the flow of the campaign’s visual messaging. When Obama won the presidency, he shattered the urban legend circulated since the McGovern campaign that cool innovative posters guaranteed a loss. 2008 was the greatest output of campaign poster art ever; however in 2012 the art community did not respond to the president’s re-election with the same enthusiasm. A number of outstanding posters were designed, many of them by the artists and designers in in Obama’s downtown Chicago campaign headquarters (see figure 31).

Figure 31 2012 Bruce Springsteen concert for Barack Obama

Source: Courtesy of author’s collection.

Sometime in the future, not likely in 2016, perhaps a candidate will run that again sets off an outpouring of political posters, but given the fluid nature of American politics, a dynamic process often determined by inadvertence, it is impossible to predict when that may happen. It is possible, however, that the great American political poster, like so much print media, is a thing of the past; that these eye titillating enticements will no longer be hanging around us in plain sight. If that is the case, the treasure trove of campaign posters created in campaign 2008 will become known as a magnificent last hurrah in a history that begin in the 1840s and continued for nearly 180 years.