“I have lived to realize the great dream of my life—the enfranchisement of women. We are no longer petitioners, we are not wards of the state, but ‘free and equal citizens.’”

— Carrie Chapman Catt, after ratification of the Nineteenth AmendmentWhen women gained the national right to vote 100 years ago, remarkable possibilities for their voice and presence in politics opened. However, despite gains in women’s representation, numerous gaps continue to exist in which adult women engage less in politics than men. In identifying and explaining adult gender gaps, little attention has been given to whether gaps emerge among children. This is a pressing issue because children’s perceptions are likely to influence their participation as adults. This article explores whether and how girls and boys differently view politics and their role in it. We report survey data from more than 1,600 children ages 6 to 12 to explore basic gender gaps in political interest and ambition. We argue that these results may reveal the roots of a larger problem: 100 years after women gained suffrage, girls still express less interest and enthusiasm than boys for political life and political office.

The struggle for suffrage in the United States was fought at the local, state, and national levels, with women organizing, lobbying public officials, pressuring parties, and running for office to push political parties, gatekeepers, and political elites to extend women the right to vote (McConnaughy Reference McConnaughy2013; Ondercin Reference Ondercin, McCammon and Banaszak2018; Teele Reference Teele2018; Wolbrecht Reference Wolbrecht2000). These activities, it was assumed, would translate into women becoming full political citizens after suffrage. Moreover, that political citizenship would provide women’s political equality.

After the United States ratified the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920 and gave whiteFootnote 1 women the national right to vote, the national narrative became one of “disappointment” with the low level of women’s engagement in politics (Rice and Willey Reference Rice and Willey1924). The subsequent women’s movement, civil rights movement, and increases in women’s education and workforce participation also provided promising developments for increasing gender equality in political involvement and representation. However, gender inequality persists today. Women are less engaged in politics across every form of political participation except voting, including political knowledge, participation, and ambition (Coffé and Bolzendahl Reference Coffé and Bolzendahl2010). These differences mean that women’s voices are weak or absent from many political arenas.

We might expect these gaps to disappear as younger generations—socialized in seemingly promising times for gender equality—replace older generations in our polity (Diekman and Eagly Reference Diekman and Eagly2000). These expectations have not yet been fulfilled. Indeed, our data of more than 1,600 students, grades 1–6, show that elementary school children already display gender gaps in which girls, particularly white girls, report lower levels of political interest and ambition than boys. Despite women gaining suffrage rights 100 years ago, our findings indicate that children’s early socialization to politics is gendered and that proactive steps and interventions must be taken to encourage girls to view themselves as vital members of the polis.

Despite women gaining suffrage rights 100 years ago, our findings indicate that children’s early socialization to politics is gendered and that proactive steps and interventions must be taken to encourage girls to view themselves as vital members of the polis.

Background

Soon after the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified, researchers noted that women were not turning out to vote at the same rate as men (Rice and Willey Reference Rice and Willey1924). However, early analyses cautioned patience: with time, women’s equality was coming. Apart from women now outvoting men, the dream that suffrage would achieve broader political engagement for women has not yet materialized. The increase of women in the workforce, the women’s movement beginning in the 1960s, and the so-called Year of the Woman in 1992 have not resulted in equal rates of political engagement or interest between men and women. Moreover, women continue to be underrepresented in elected political offices at the federal (Dietrich, Hayes, and O’Brien Reference Dietrich, Hayes and O’Brien2019), state (Osborn Reference Osborn2014), and local (Holman Reference Holman2017) levels.

Despite suffrage and rapid changes thereafter, evidence documents gender differences—adult women have less enthusiasm for politics generally (Preece Reference Preece2016) and for political careers and seeking office (Crowder-Meyer Reference Crowder-Meyer2018; Schneider et al. Reference Schneider, Holman, Diekman and McAndrew2016)—but also focuses on white women’s experiences. Different (and often smaller) gaps emerge for women of color (Farris and Holman Reference Farris and Holman2014; Silva and Skulley Reference Silva and Skulley2019). These gender gaps are consequential because political interest predicts many forms of political action, including running for political office. Because running for office must occur before holding office, political interest gaps contribute to the underrepresentation of women’s voices in formal political activism and in political office.

It is not clear when these gaps begin because most studies of the gender gaps in political interest and ambition examine adult American men and women (Burns, Schlozman, and Verba Reference Burns, Schlozman and Verba2001; Silva and Skulley Reference Silva and Skulley2019). Research from political socialization and gender studies highlights the importance of understanding what girls and boys think about politics early on in life.

We argue that gender gaps may exist among children due to a gendered socialization process. From an early age, children experience gender socialization (Letendre Reference Letendre2007). Boys are encouraged to develop traits associated with leadership and agency and girls to develop traits oriented toward caring and interpersonal relations (Diekman and Murnen Reference Diekman and Murnen2004). According to social role theory (Eagly and Wood Reference Eagly, Wood, van Lange, Kruglanski and Higgens2012; Schneider and Bos Reference Schneider and Bos2019), when children observe more men than women in public-sphere roles, they infer that male-typical traits are needed to be successful in those roles.

There also are reasons to believe that the political socialization process—that is, how children learn not only about the world generally but also about politics—is gendered. For example, young women (compared to young men) are less likely to have their parents speak to them about politics and less likely to have anyone encourage them to run for office (Lawless and Fox Reference Lawless and Fox2013). Because children learn that men predominantly hold political office and their social studies curricula is likely to emphasize men’s contributions to US politics (Cassese, Bos, and Schneider Reference Cassese, Bos and Schneider2014; Lay et al. Reference Lay, Holman, Bos, Greenlee, Oxley and Buffett2019), they associate men and masculine traits with success in politics. Indeed, “both boys and girls learn that adult political expression is more of a male than female gender role” (Jennings Reference Jennings1983, 365). Yet, when gender cues exist in their political surroundings, girls pay attention to these cues. Adolescent girls’ political interest is bolstered in response to a highly visible, novel woman running for political office (Campbell and Wolbrecht Reference Campbell and Wolbrecht2006). Furthermore, recent research on interest in politics since the 2016 election suggests that teenage girls are paying close attention to the ways that gender is discussed in politics (Campbell and Wolbrecht Reference Campbell and Wolbrecht2019). Like adult women (Freeman Reference Freeman2002), girls also may be likely to participate in nonformal political activism (Brinkman Reference Brinkman, Bos and Schneider2016), including working for social and political change.

At the same time, we know little about gender gaps in traditional measures of participation, including political interest and ambition, before adulthood. Our research filled this scholarly gap by directly asking children about their political interest and ambition, which allowed us to measure and examine gender differences. One century after women’s suffrage, we demonstrate myriad ways that girls continue to be socialized to underestimate their political potential.

One century after women’s suffrage, we demonstrate myriad ways that girls continue to be socialized to underestimate their political potential.

METHODS

We examined girls’ and boys’ political interest and ambition through data collected in interviews and surveys with primary-school–aged children in late 2017 and early 2018. Researchers recruited students from 18 elementary schools across four research locations to participate (Oxley et al. Reference Oxley, Holman, Greenlee, Bos and Celeste Lay2020). After obtaining parental consent and student assent, we interviewed (i.e., first, second, and some third graders) or surveyed (i.e., some third and all fourth through sixth graders) each student.

FINDINGS

We used a battery of questions adapted from science education to measure interest in politics. Students provided their level of agreement with the following statements using a four-point scale (i.e., from strongly disagree to strongly agree): “Politics, government, and history is something I get excited about”; “I am curious to learn more about politics, government, history, and current events”; “I would like to have a job in government or politics in the future”; and “Learning about history and how the government works is boring” (reverse coded). We examined responses on each statement as well as an averaged scale of all items.

To examine gender differences in political interest, we used a simple regression model (see the online appendix) with controls for race and ethnicity and clustered errors based on research location. In figure 1, which presents the differences between boys and girls, the dots indicate the coefficient and the bars indicate the confidence intervals (95%). Coefficients that are below the zero line indicate that boys expressed higher levels of interest than girls, holding location and race and ethnicity constant. We found that girls express lower levels of aggregate interest, as compared to boys, suggesting that even at an early age, girls are not socialized to see politics as an area of interest and excitement. These results are particularly apparent among white girls, who express lower levels of interest and less positive affect toward political jobs. Black girls, in comparison, are less excited about politics in comparison to all boys.

Figure 1 Gender Differences in Interest in Political Materials

Figure 2 Gender Differences in Interest in Political Jobs as Adult

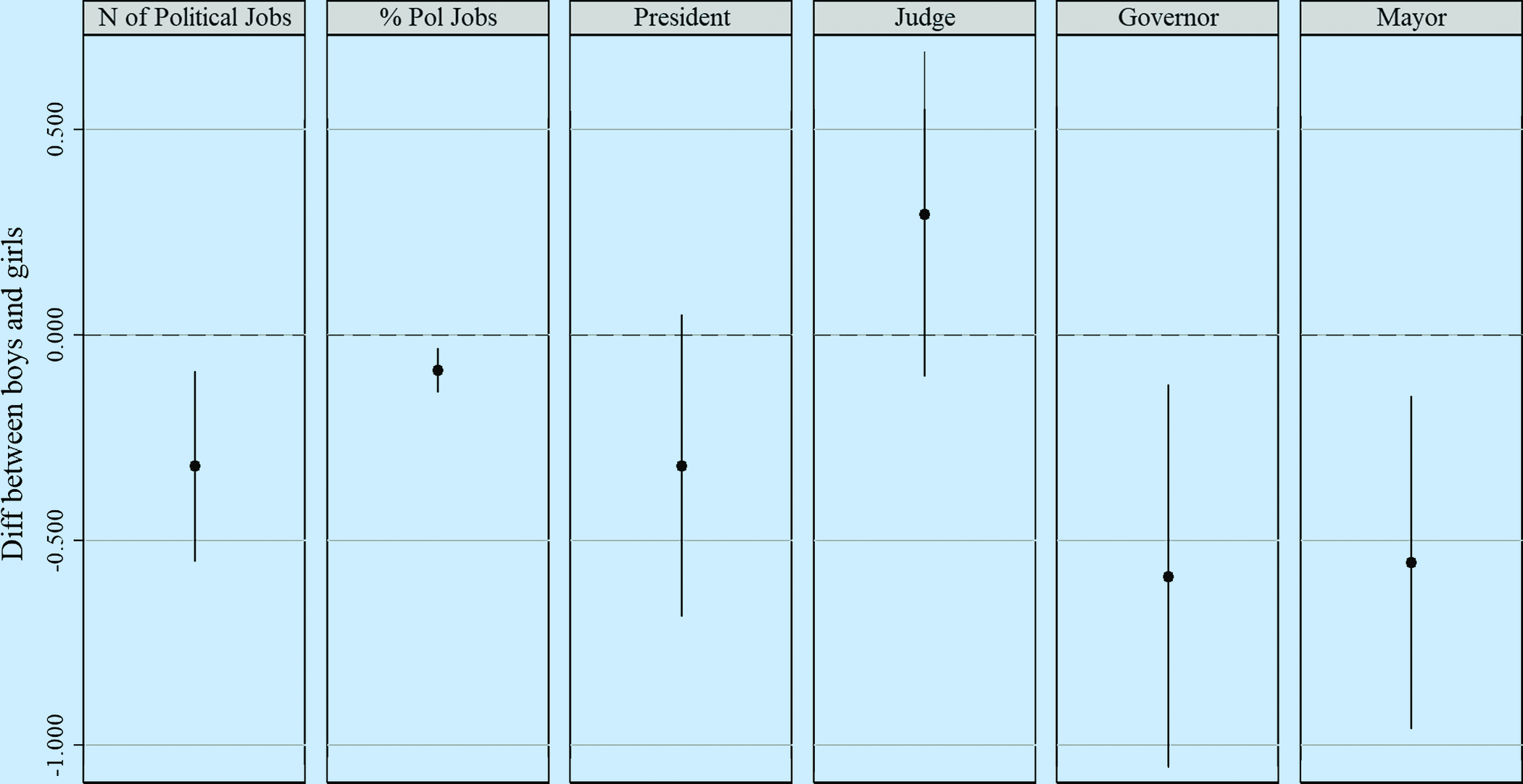

To examine whether gender gaps in political ambition exist among children, we asked a subsample (N=492) of students to “Check all the jobs you would like when you are older,” selecting from a list that included jobs such as business owner, teacher, doctor, and four political jobs: president, governor, judge, and mayor. We examined the individual political leaders, the total number of political jobs selected, and the share of jobs selected that were political. The results are shown in figure 2.

We again found gender differences, with girls (compared to boys) checking fewer political jobs overall and a lower share of political jobs from the total jobs selected. We found that girls do not select jobs such as mayor and governor, whereas judge—a job that could be seen as political or not—has a positive, insignificant coefficient for gender. Again, these results are stronger for white girls, who select fewer political jobs overall and are less likely to list president, governor, or mayor. Although black girls select fewer jobs overall, they do not select any one job at a lower rate.

DISCUSSION

Despite 100 years of white women’s voting rights and visible gains made by women with regard to participating in politics and holding elected office, women’s political engagement lags behind men. Our results show that this also is true among children: compared with boys, girls are less interested in politics generally and less interested in political careers specifically. These results may help explain the roots of myriad gender gaps between adult men and women.

Our findings indicate a pressing need to understand more about when and how children develop perceptions of politics generally, about how political socialization is gendered, and to what effect. Understanding the causes of early gender gaps will chart a course for further understanding of how to address childhood political gender gaps. Research demonstrates the importance of creating gender-equitable curricula (Cassese, Bos, and Schneider Reference Cassese, Bos and Schneider2014) and women role models in politics (Campbell and Wolbrecht Reference Campbell and Wolbrecht2006).

One hundred years ago, women’s suffrage brought a promise for women’s equality. That early promise is still unfulfilled. What is clear is that simply adding women to the political sphere a century ago by granting them suffrage rights did not result in fundamental changes to political institutions. It falls to adults to address socialization processes in order to engage girls more fully in politics.

These efforts could transform our political world to a more inclusive space in which girls and women are descriptively and substantively represented in all aspects of the political process.

These efforts could transform our political world to a more inclusive space in which girls and women are descriptively and substantively represented in all aspects of the political process.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1049096520000293.