FIELDWORK AND RESEARCH

During the 1999 excavation of a waterlogged Bronze Age timber circle on Holme-next-the-Sea beach (Holme I; Figs 1 & 2), a rapid walkover survey revealed two horizontal logs and an oval of wickerwork (structure 126; Brennand & Taylor Reference Brennand and Taylor2003, 9–12; Fig. 3). These were subsequently dated to the Early Bronze Age, either contemporary with Holme I or a few centuries earlier (Brennand & Taylor Reference Brennand and Taylor2003, 10; Table 1; Fig. 4). By 2003 erosion had exposed part of an outer palisade and enough information was available to interpret the structure as a second timber circle (Holme II; Norfolk Historic Environment Record (NHER) 38044; Brennand & Taylor Reference Brennand and Taylor2003, 8–12; Fig. 4).

Fig. 1 Location map

Fig. 2 2003–8 survey area, archaeological features, and findspots

Fig. 3 Inner and central settings at Holme II, including wickerwork, c. 1999 (© John Lorimer)

Fig. 4 Probability distributions of dates from Holme, together with the tree-ring felling date (2049 bc). The distributions are the result of simple radiocarbon calibration (Stuiver & Reimer Reference Stuiver and Reimer1993)

Table 1 Holme II Radiocarbon Results

In early 2003 a Norfolk Archaeological Unit (NAU) walkover survey examined a 3.5 km long stretch of Holme beach (Figs 1 & 2). It recorded a number of features, including an increasingly exposed Holme II. The resulting Management Plan explored a range of management scenarios for Holme II but, given the opposition to the excavation of Holme I (Watson Reference Watson2005, 38–43 & 47–53), acknowledged that large-scale excavation was not a realistic option (Norfolk Archaeology & Environment 2003, 14–15). Instead it outlined a five-year monitoring programme for selected features (including radiocarbon dating). This was carried out by the NAU between July 2003 and May 2008 (Ames & Robertson Reference Ames and Robertson2009).

Since the end of the formal monitoring project the Norfolk Wildlife Trust and Norfolk County Council Historic Environment Service’s Monuments Management Project have continued monitoring. Observations made during this work led to the dendrochronological assessment of Holme II (Tyers Reference Tyers2011) and subsequent dendrochronological dating of the felling of timbers within it to the spring or summer of 2049 bc (Robertson Reference Robertson2014; Tyers Reference Tyers2014).

This paper describes the results of the walkover survey, monitoring, and dendrochronology with specific focus on Holme II and the other Bronze Age features of Holme beach. Other publications cover the 2003 walkover survey and monitoring project’s aims, methodology, and observations on coastal processes (Robertson & Ames Reference Robertson and Ames2015) and early medieval fishweirs (Robertson & Ames Reference Robertson and Ames2010).

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF HOLME II

Although over 100 timber circles are known to have been constructed in Neolithic and Bronze Age Britain (Gibson Reference Gibson2005, 155–73), Holme II is one of only three where surviving waterlogged timbers have been discovered. The first timber circle known to have waterlogged timbers, Bleasdale in Lancashire, was excavated in 1898–1900 and the 1930s (Varley Reference Varley1938). The second was Holme I. At both Holme sites waterlogging ensured the survival of evidence not normally found on equivalent dry land sites, including the timbers themselves, evidence for woodworking, and material suitable for dendrochronological dating.

British timber circles tend to be dated by radiocarbon dating, associated artefacts, and/or their associations with other features (Gibson Reference Gibson2005, 59–77). To date only two have been dated by dendrochronology: Holme I and Holme II. The central post from the Navan 40 m structure – one of Ireland’s Iron Age timber circles – has also been subject to dendrochronological dating (Baillie Reference Baillie1988, 39).

The felling date of 2049 bc for the timbers used to build Holme II is particularly important as it demonstrates that Holme I and Holme II were built at precisely the same time. In doing so, it provides us with the only known example of two monuments constructed simultaneously in British prehistory. It also places Holme II firmly within the accepted date range of c. 3000–900 bc for British timber circles (Gibson Reference Gibson2005, 62–5). This ensures that the data provided by the timbers themselves, as well as the layout and form of Holme II, can be used to enhance the studies of other British timber circles. Four main elements identified within Holme II – an outer palisade, an inner arc, an inner fence of stakes with wickerwork, and a central setting (Figs 3 & 5–7) – have been identified in other British timber circles; it is therefore possible to draw direct comparisons between Holme II and other structures with similar features.

Fig. 5 Holme II, July 2003 (David Robertson © NPS Archaeology)

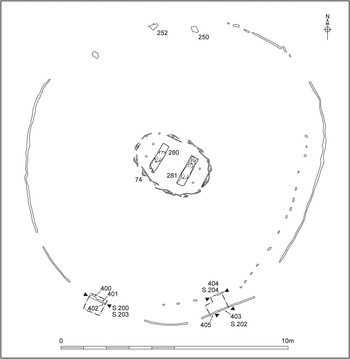

Fig. 6 Composite plan of Holme II, based on records made in 1999, 2001, 2003–8, and 2013

Fig. 7 Inner and central settings at Holme II, with the outer palisade behind, July 2003 (David Robertson © NPS Archaeology)

Comparisons between Holme II and other timber circles can help us understand why Holme II was built and how it was used. They allow glimpses of possible structuring beliefs of society in the Early Bronze Age, as well as the actions of individuals and groups. They suggest that conceptions of a world of the dead may have been influential and rites of separation and incorporation (Barrett Reference Barrett1996, 397–8) could have been important.

The remains of freshwater marshes contain at least one trackway and direct evidence for coppicing in Early Bronze Age Britain. Very few examples of coppiced timbers and stools have been found in situ, giving those at Holme beach particular importance.

The information presented in this paper has been collected over nearly 16 years. The challenges of working in Holme beach’s intertidal zone mean that without long-term monitoring and the resulting dating programme, much information would have been lost (Robertson & Ames Reference Robertson and Ames2015). If it had been lost, the significance of Holme II and the freshwater marshes would not have been understood in such detail.

GEOLOGY, TOPOGRAPHY, AND NATURE CONSERVATION

Holme beach lies at the western end of the north Norfolk coast, close to the north-eastern extent of the Wash (Fig. 1). The beach is bordered by sand dunes to the south and by Thornham harbour channel to the east. To the south of the dunes are low-lying freshwater marshes and Holme-next-the-Sea village. Holme beach forms part of the Holme Dunes National Nature Reserve and is covered by multiple biodiversity designations. It is managed by the Norfolk Wildlife Trust and is particularly important as it contains a variety of habitats that provide important food sources and breeding grounds for both resident and migratory birds.

The drift geology of the area comprises a thin basal freshwater peat (c. 9450–6950 cal bc; Brennand & Taylor Reference Brennand and Taylor2003, 2) which is covered by a variable sequence of intertidal clays and silts. The clays/silts developed in mudflat and saltmarsh conditions from c. 5900–4850 cal bc (Brennand & Taylor Reference Brennand and Taylor2003, 2) and are visible in places on the beach. Both of the timber circles were constructed in this environment, close to the point of the highest spring tides, behind sand dunes (Brennand & Taylor Reference Brennand and Taylor2003, 59–61 & 64).

From 2140–1780 cal bc (GU-6015; Ames & Robertson Reference Ames and Robertson2009, appx 30) a freshwater reed swamp and alder carr developed behind sand dunes of increasing height (Brennand & Taylor Reference Brennand and Taylor2003, 59–61). The upper intercalated peat that formed in this environment survives as a series of eroded peat beds across the beach. Iron Age pottery from the peat beds suggests freshwater habitats were still present late in the prehistoric period. Although erosion of the upper surface of the peat means that it has not been possible to determine when these reverted to intertidal environments, it seems probable that this had occurred by the early medieval period (Robertson & Ames Reference Robertson and Ames2010, 341).

HOLME II

(David Robertson & Maisie Taylor)

Holme I and II are the only structures so far identified within the sequence of intertidal clays/silts that developed in saltmarsh and mudflat conditions. The remains of saltmarsh and mudflat plant macro-fossils, insects, and microfauna were recovered from these deposits during excavation of Holme I (Brennand & Taylor Reference Brennand and Taylor2003, 44–9 & 55) and the dendrochronology fieldwork (Fryer Reference Fryer2014). A red deer antler and horse bones are evidence of the animal species that used these habitats (NHER 56717, 55966 & 60562; Curl Reference Curl2015).

Holme II (Fig. 5) has been archaeologically recorded on over 20 occasions since 1999. Until July/September 2004 progressive erosion led to the exposure of more of the structure and the loss of at least one timber. Since then the circle has regularly been entirely covered by sand (Robertson & Ames Reference Robertson and Ames2015). At no one time has the whole circle been visible.

Three test pits (TP) have been excavated. The first, adjacent to timber 304/400 and measuring 0.5 m square, was dug in March 2004 to determine the length of the upright timbers and help estimate how long they would be likely to survive. The other two formed part of the 2013 dendrochronology fieldwork (Fig. 6). TP1 – 0.75 m square and up to 0.6 m deep – was deliberately located in the area of the 2004 TP to minimise disturbance to archaeological deposits. TP2 – L-shaped and measuring 0.85 m by 0.65 m by 0.65 m deep – was sited to study timbers from two elements of the structure.

The outer palisade

The outer palisade is made of split oak (Quercus sp.) timbers set side-by-side (Figs 5–8). There are a number of gaps in the circumference, but it is not clear if these represent original gaps, loss of timbers to erosion, or areas where timbers are yet to be revealed. In plan it forms a rather eccentric oval rather than being truly circular or oval. This means that there is no axis of symmetry and it is difficult to identify a principal orientation, but the longest observed internal diameter (14 m) is aligned roughly north-east to south-west. The shortest observed internal diameter (12.85 m) is orientated roughly WNW to ESE.

Fig. 8 Sections from the three test pits at Holme II

Initially what were thought to be individual timbers within the palisade were drawn in plan; most appeared to be thin (0.06–0.08 m) and tangentially split with occasional radially split and short, horizontal pieces. However, the excavation of the TPs in 2004 and 2013 made it clear that it was not possible to be certain of timber widths based on the uppermost eroded sections; in some cases what looked like two timbers turned out to be eroded sections of a single timber. As a consequence, it has not been possible to establish the exact number of timbers used in the palisade or a range for their widths; Figure 6 shows in detail the six timbers examined in TPs 304/400 and 401–405 (Table 2; Figs 8–9).

Fig. 9 Cross sections of timbers from Holme II

Table 2 Timbers from Holme II

Four, possibly five, of the timbers studied in the TPs were tangentially split then trimmed square (Table 2). It is usually easier to split larger trees (over 0.4 m diameter) tangentially than it is radially and doing so produces less waste; in comparison it is usually easier and less wasteful to split smaller trees (under 0.4 m diameter) radially rather than tangentially. Evidence from Flag Fen suggests that tangential splitting was not common in the Bronze Age and is generally associated with larger trees (Taylor Reference Taylor2010, 90–2). The presence of tangentially split timbers suggests the use of some larger trees to build Holme II’s palisade. Most of the timbers in Holme I’s palisade were simple half splits, with the exceptions in its north-eastern panel (Brennand & Taylor Reference Brennand and Taylor2003, 17, figs 14 & 19).

Although a very small sample, the radii prepared for ring counting gives a range of minimum diameters from 0.21–0.57 m, albeit none is the size of the central tree from Holme I which had a maximum diameter of 1.2 m (Brennand & Taylor Reference Brennand and Taylor2003, 7). The range of diameters for the trees used for the Holme I palisade (excluding the forked entrance timber) was 0.2–0.4 m (Brennand & Taylor Reference Brennand and Taylor2003, appx). The actual size of the Holme II timbers examined in detail ranges from 0.3–0.36 m wide (not counting the incomplete and distorted ones) which sits quite comfortably within the range of sizes of the timbers from the Holme I palisade (0.205–0.451 m; Brennand & Taylor Reference Brennand and Taylor2003, appx).

There was no clear evidence for cut features in any of the three TPs. The only variation identified was in TP1, where there was a greater concentration of organic material in the silty clays immediately adjacent to the outer palisade than those further away. It is likely that the greater concentration of organic material was present in the fill (306) of a trench cut to hold the timbers, whereas the lower concentration was characteristic of undisturbed silty clay deposits (406).

The inner arc

An inner arc of oak timbers placed between 0.5 m and 0.25 m apart was set about 0.4 m inside the outer palisade (Fig. 6; Supplementary Fig. S1). It is possible that this element was only constructed in these areas, but it is equally likely that it comprised a full circuit with timbers lost to erosion or that its full extent is yet to be revealed. Although two split oak timbers (250 and 252) were recorded in the north of Holme II, it was not clear if these formed part of the inner arc or had fallen inwards from the palisade.

In 2003, 15 oak timbers from the inner arc were examined, while TP2 allowed detailed examination of timber 404 (Table 2; Figs 8–9). Of those timbers where analysis was possible, seven may have been tangentially split while five were potentially radially split. Erosion made it difficult to identify the way in which timber 404 had been split.

The inner fence

In the centre of the palisade was an oval setting of 15 upright oak roundwood stakes, through which two courses of thin oak wicker were woven (Figs 3 & 5–7; Brennand & Taylor Reference Brennand and Taylor2003, 10–12). This fence had a maximum length of 3.55 m (aligned roughly north-west to south-east) and a width of 2.45 m (aligned roughly north-east to south-west).

The stakes and wattle are all within the range of modern hurdling (Morgan Reference Morgan1988, table 2) rather than basketwork, and the structure would have been rigid and quite substantial. There is not much information about oak used for wattling but Morgan’s study (Reference Morgan1988, table 1) suggests that it is very rare/absent in the Neolithic and Bronze Age. Oak wattle would be heavy and durable, but quite hard to handle because oak is less flexible than the usual wattle species such as hazel, willow, and alder.

The central setting

The inner fence surrounded two cut and trimmed oak logs (Table 2; Figs 3 & 5–7) placed 0.9 m apart, parallel to each other, and aligned north-east to south-west. Although erosion showed that both logs had been placed horizontally on silts and clays, it was not clear whether this was within a pit (Brennand & Taylor Reference Brennand and Taylor2003, 10) or on the ground surface. Following the loss of the eastern log (76/281) to the sea in October 2003, in March 2004 the second (75/280) was salvaged and transported to Flag Fen for further study and dating.

When first seen both logs had surviving bark in places and clear signs of woodworking, including toolmarks, one trimmed end, one end with the classic V-shape of a felled tree (trimmed from both directions), and rebates with chamfered ends and flat bottoms in their upper surfaces. Two hundred and eighty-one had a trimmed side branch while 280 had a hole in its south-western end (Fig. 10), possibly a mortise or tow hole. All woodworking appeared to have been done with a metal axe, although erosion meant that it was not possible to record blade sizes or stop marks. The shaping on the upper surfaces of the logs can be paralleled with joints from Flag Fen (Taylor Reference Taylor2001, 309, nos 33, 34, & 37). Housing joints, albeit much smaller, were quite common in the Bronze Age. They are not difficult to cut and may have had many uses.

Fig. 10 Western central log from Holme II (280), with the tow hole and vertical marks of uncertain origin (possibly eroded mollusc tunnels), July 2001 (© John Lorimer)

Two upright oak roundwood stakes 0.38 m apart were located to the west of the western log, with another two 0.53 m apart to the east of the eastern log. The maximum distance between the eastern and western stakes was around 2.3 m.

Dendrochronology

(Ian Tyers)

Six timbers exposed in TPs 1 & 2 and the western central log (280) were sub-sampled for dendrochronology. Standard preparation and analysis methods (English Heritage 1998, 7–14) were applied to each suitable sample. Where bark or bark-edge survives, a felling date precise to the year or season can be obtained. If some sapwood survives, a broad estimate for the number of missing rings (which varies by region) can be applied to the end-date of the heartwood. A minimum of 16 rings and a maximum of 54 rings as a sapwood estimate, derived from the material from Holme I (Groves Reference Groves2002), has been used for the Holme II timbers.

Six of the seven samples were suitable for measurement (Table 3). Five of the tree-ring series from these were found to cross-match each other (Table 4) and the composite sequence from Holme I (Table 5), where the individual series dating position against the latter independently confirmed the internal cross-matching. The Holme II composite sequence dates from 2376–2049 BC inclusive (Table 6). The timber sampled from the inner arc (404) was heavily eroded, retains no sapwood, and contained too few rings for tree-ring analysis.

Table 3 Holme II Dendrochronology Results

H/S is heartwood/sapwood edge; ?H/S is possible heartwood/sapwood edge; Bs is bark after incomplete annual ring. Interpretations based on 16–54 sapwood rings. Sample 402 contains an unmeasured band of unresolved rings marked ‘?’

Table 4 The T-Values (Baillie & Pilcher Reference Baillie and Pilcher1973) Between the Five Dated OAK Timbers from Holme II

Key:– is a t-value less than 3.0. These series were combined to form the composite sequence HNS2–T5 used in Table 6

Table 5 The T-Values (Baillie & Pilcher 1973) Between the Five Dated Timbers from Holme II and the Composite Sequence from the Holme I (Groves Reference Groves2002)

Table 6 Example T-Values (Baillie & Pilcher 1973) Between the Composite Sequence HNS2–T5 Constructed from the Five Dated Series from Holme II and Prehistoric OAK Reference Data

Dating

The five samples from outer palisade timbers yielded four dateable tree-ring sequences (the exception was timber 402 which contained an unmeasurable band of narrow rings between two short, measurable, but undated series). Bark-edge survived on one of these timbers (401), the heartwood/sapwood boundary survived on another (400), and the possible boundary on another (403). No sapwood was present on the remaining dateable timber (405). Samples 403 and 405 were derived from the same tree so they can both be given the same interpretation. Making allowances for minimum and maximum likely amounts of missing oak sapwood provides individual felling dates, or felling date ranges, or terminus post quem dates for each of the dateable oak timbers (Fig. 11; Table 3). Complete to bark edge and with an incomplete ring for 2049 BC, timber 401 was felled in the spring or summer of 2049 bc. The calculated felling date ranges for the other oak samples indicate that this group of timbers was either precisely or broadly contemporaneous (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11 Bar diagram showing the absolute dating positions of the five dated tree-ring sequences for samples from Holme II; the composite sequence from Holme I is shown for comparison. The interpreted felling dates are also shown for each sample. White bars are oak heartwood, black and white hatched bars are oak sapwood

The sample obtained from the western central log (280) yielded a dateable tree-ring sequence complete to bark edge. The incomplete ring for 2049 bc indicates that this timber was felled in the spring or summer of 2049 bc, precisely contemporaneous with the felling of timbers from the outer palisade (Fig. 11).

Discussion

The comparison of the information derived from a small sub-sample of the timbers in Holme II and the previous analysis of 55 timbers obtained from Holme I is instructive. Fifty of the Holme I samples were intact to bark-edge (49 timbers from the outer palisade and the central upturned tree). Forty-nine of these were felled in 2049 bc; in each case the final ring was likely to be incomplete indicating felling in spring or early summer. The one exception had an apparently complete ring for 2050 bc but showed no signs of growth for 2049 bc. This timber could have been felled as early as the start of the dormant season in 2050 bc but as late as spring 2049 bc and it may have been an individual tree that started its growth later than its contemporaries. The presence of material with precisely the same bark-edge date at Holme II clearly demonstrates that the two circles were constructed at the same time.

The Holme I palisade utilised a relatively small number of quite uniform trees. The site master sequence is 181 years in length, and it was interpreted as being constructed from 15–20 oak trees mostly of 100–150 years lifespan and 0.2–0.4m diameter. Holme II samples 280, 401, 403, and 405 are similar to this material, and there is no reason to suppose that they were derived from a different part of the contemporaneous landscape. In contrast, with 294 rings, Holme II sample 400 is different from all the other material from both palisades. It retained no sapwood or pith but it is reasonable to suppose that it was contemporaneous with the others. Making minimal allowances suggests that this timber was derived from an at least 350-year-old oak tree, of potentially 0.6 m diameter. The only other long-lived tree known from either circle is the upturned tree in the centre of Holme I which was not fully sampled but is thought to have had 250–350 rings, extrapolated from the sampled partial radius.

THE FRESHWATER MARSH

Within a few centuries of the construction of Holme I and II reduced tidal influence and an influx of fresh groundwater encouraged the development and maintenance of freshwater reedbed and carr woodland around the monuments (Brennand & Taylor Reference Brennand and Taylor2003, 59–61). The peat beds that developed in these conditions contain a trackway, two possible trackways, coppiced stools, groupings of coppiced timbers, numerous fallen tree trunks and branches (including wood group 79; Brennand & Taylor Reference Brennand and Taylor2003, 12–13; NHER 38046; Figs 12–13), stumps, and root systems.

Fig. 12 Probability distributions of dates from Holme Beach timber structures. The distributions are the result of simple radiocarbon calibration (Stuiver & Reimer Reference Stuiver and Reimer1993)

Fig. 13 Probability distributions of dates from Holme peat beds

Radiocarbon dating

(W. Derek Hamilton & Gordon Cook)

The results (Tables 1 & 7–8) are conventional radiocarbon ages (Stuiver & Polach Reference Stuiver and Polach1977) and are quoted in accordance with the international standard known as the Trondheim convention (Stuiver & Kra Reference Stuiver and Kra1986). The calibrations of these results, which relate the radiocarbon measurements directly to the calendrical time scale, are given in Tables 1 and 7–8 and Figures 4 and 12–13. All have been calculated using the datasets published by Reimer et al. (Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, Hatté, Heaton, Hoffmann, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and van der Plicht2013) and the computer program OxCal v4.2 (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey1995; Reference Bronk Ramsey1998; Reference Bronk Ramsey2001; Reference Bronk Ramsey2009). The calibrated date ranges cited are quoted in the form recommended by Mook (Reference Mook1986), with the end points rounded outward to 10 years. The ranges in Tables 1 and 7–8 have been calculated according to the maximum intercept method (Stuiver & Reimer Reference Stuiver and Reimer1986); the probability distributions shown in Figures 4 and 12–13 are derived from the probability method (Stuiver & Reimer Reference Stuiver and Reimer1993).

Table 7 Timber Structures Radiocarbon Results

Table 8 Coppiced Wood Radiocarbon Results

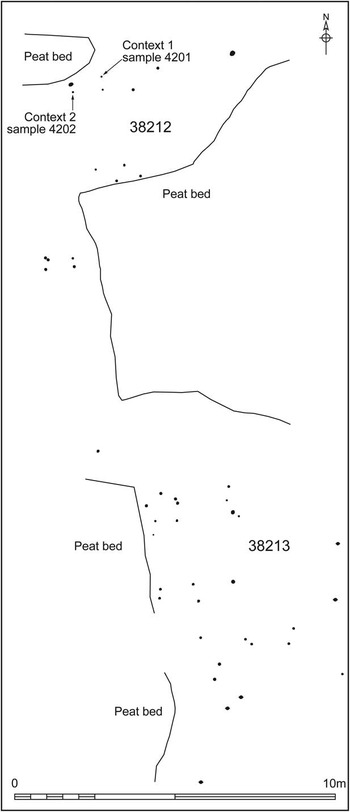

Middle Bronze Age stake group (NHER 38212/38213)

About 250 m to the north-west of Holme I and spread over an area measuring 24×10 m were 39 posts and stakes (Figs 2 & 14). In a number of places two parallel rows of timbers were present, but it was not possible to identify a clear and consistent alignment. The timbers ranged in diameter from 0.06–0.17 m and those sampled were roundwood: one willow/poplar and the other alder/hazel (Alnus glutinosa/Corylus avallana). Radiocarbon measurements (GU-6026–7; Table 7; Fig. 12) are statistically consistent (T’=0.0, ν=1, T’(5%)=3.8), suggesting that these two timbers are likely to be contemporary and dating this arrangement to 1610–1430 cal bc (GU-6027).

Fig. 14 Stake group NHER 38212/38213

Although the purpose of this post group is not certain, it is possible that some of the parallel rows were designed to hold brushwood in place and therefore form a trackway. If this was the case, the broad-width of the group may reflect repair and/or reorientation over time.

Middle Bronze Age timbers (NHER 38205)

Approximately 980 m west of Holme I were seven upright timbers (Fig. 2), possibly arranged in two north–south rows. Two of the timbers were sampled – one was willow/poplar (Salix sp./Populas sp.) roundwood and the other was a quarter split piece of alder (Alnus glutinosa). Radiocarbon determinations on these (GU-6024–5; Table 7; Fig. 12) are statistically inconsistent (T’=19.2, ν=1, T’(5%)=3.8), suggesting the use of material of different ages. The latest date provides the best estimate for its construction around 1620–1400 cal bc (GU-6025). The purpose of this feature is uncertain.

Middle to Late Bronze Age trackway (NHER 38221)

About 20 m to the east of Holme II was a sinuous trackway (Figs 2 & 15). It was aligned roughly north-west to south-east, at least 40 m long, and the timbers used in its construction spread across an area 1.5–3 m wide. Although over 70 stakes were recorded in situ, at least some of the 100+ transverse timbers and branches had probably been moved from their original location by water action. This is thought particularly likely given the fact that the trackway lay in a channel cut through the peat beds (possibly a channel that had eroded as result of its presence).

Fig. 15 Trackway NHER 38221

The timber stakes appeared to be irregularly spaced, with paired timbers and parallel rows in some areas. Most had suffered from water erosion, which made it difficult to identify wood species and exact diameters of the timbers used. Recorded diameters ranged from 0.03–0.13 m. The two stakes sampled were ash (Fraxinus excelsior): one was from roundwood, the other half split.

Most of the transverse timbers and branches were orientated along the line of the stake alignment, although in some instances they were placed at right angles to the stakes. They appeared to be irregularly spaced, but the recorded locations are more likely to reflect timbers that have survived the sea rather than the trackway’s original form. Of the four sampled timbers, two were alder, one ash, and one oak. Roundwood, half split and tangentially split pieces, and eccentric pieces of wood were all present. The two radiocarbon measurements from this structure, one from a stake and one from a cross timber (GU-6032–3; Table 7; Fig. 12), are statistically consistent (T’=1.3, ν=1, T’(5%)=3.8). They suggest that the trackway construction was a single event that can be dated to 1210–900 cal BC (GU-6032).

Coppiced trees

(David Robertson & Maisie Taylor)

In the west of the peat beds, 900–1500 m west of Holme I, were four groups of rectilinear arranged wood (NHER 38195, 38197, 38918 & 38199/38200; Fig. 2). The identification of many coppiced timbers at NHER 38199/38200 suggests that all four were collapsed stands of coppiced trees (the two groups with possible posts are described below). The remains of a single large coppiced stump were identified immediately north-east of Holme II (Supplementary Fig. S2).

NHER 38199/38200 (Figs 16–17) included at least 46 pieces of horizontal wood and two possible posts. A number of the horizontal pieces lay parallel to others, with some perpendicular to these. The longest measured 7 m, with a maximum diameter of 0.4 m. Three had notches in them, possibly the result of timbers laying on top of others and causing compression, woodworking, and/or animal activity (erosion made it difficult to tell). Six were sampled: two willow/poplar, one birch (Betula sp.), and two alder (see Table 8 for radiocarbon results).

Fig. 16 Collapsed coppiced timbers NHER 38199/38200

Fig. 17 Collapsed coppiced timbers NHER 38200, with NHER 39199 in the background, November 2004 (David Robertson © NPS Archaeology)

Many of the horizontal pieces had traits indicative of coppiced stems, including surviving pieces of bole, curved bases, and narrow diameters. All the sampled pieces were from fast-grown trees, supporting the likelihood that the wood is from coppicing. The balance of probability is that relatively young trees were coppiced and allowed to regenerate. Stems then grew to maturity, before collapsing as a result of rot, wind blow, or their own weight.

NHER 38198 (Fig. 18) comprised at least 13 pieces of horizontal wood, some parallel to each other, a post, and two possible posts. Six timbers with similar alignments in the east of the group could represent collapse from a single coppiced tree. Samples were taken from the post and one horizontal – both were alder and produced statistically inconsistent radiocarbon measurements (Table 8). This suggests that the post and at least one of the horizontal timbers could represent different phases of activity.

Fig. 18 Collapsed coppiced timbers NHER 38198

Artefacts

Artefacts and faunal remains have been recovered from the peat beds since at least the early 20th century. Details of those which are directly relevant to this paper are provided below (information on the others is provided in Brennand & Taylor Reference Brennand and Taylor2003, Ames & Robertson Reference Ames and Robertson2009, and the NHER).

Before 1908 a Bronze Age battle-axe (Fig. 19.1) was recovered ‘probably from the submerged forest’ (NHER 1099). It has been classified as type IIB (Roe Reference Roe1966, 235, no. 131); the stone used has been identified as dolerite (Clough & Cummins Reference Clough and Cummins1988, 178, no. 88). Five copper alloy objects have been found unstratified on the beach (Table 9; Fig. 19): an Early Bronze Age conical button, two Middle Bronze Age palstaves, a Late Bronze Age tanged chisel, and an unidentified axe or palstave.

Fig. 19 Selected artefacts from the peat beds (all 1:2 except 2 at 1:1)

Table 9 Copper Alloy Artefacts

Ten body sherds (78 g) made from a sandy fabric were found in peat close to the trackway NHER 38221. The exterior and interior of nine are smoothed almost to a burnished finish. The other is abraded, but retains a lattice of narrow grooves on the exterior and sooting on the interior (suggesting it was subject to fire after breakage). Four of the sherds (including that with grooves) are Iron Age (Andrew Rogerson pers. comm.); the others can be tentatively assigned an Iron Age date (Ames & Robertson Reference Ames and Robertson2009, appx 28). These sherds provide a terminus post quem for the reversion of the freshwater marsh to intertidal habitats.

DISCUSSION

Constructional sequence for Holme II

(David Robertson & Maisie Taylor)

Structural development sequences have been suggested for a number of excavated timber circles (including Amesbury G71 (Barrett Reference Barrett1996, 406–7; Christie Reference Christie1967, 339–43) and Deeping St Nicholas 28 (French Reference French1994, 24–33)) and, as a consequence, it was originally thought that Holme II might have been built in a number of phases. However, the felling dates for the timbers in the palisade and central setting demonstrate that they were constructed at the same time. Although it was not possible to date the timber from the inner arc, it is perhaps most likely that the inner arc was also constructed at the same time. Radiocarbon dating suggests that the wickerwork could be of the same date.

The following single constructional sequence is proposed for Holme II:

-

∙ Two oak trees were selected and felled. The felled ends were left untrimmed but the opposite ends were trimmed flat. A tow hole was cut through the felled end of one (280). A low side branch on the other (281) was trimmed off close to the trunk, leaving a short section for use as a grip to make dragging it easier.

-

∙ The two logs were taken to the place selected for the construction and the rebates were cut into their upper surfaces. This was probably done in situ to make sure that they were the correct width and lined up. No bark was removed except for the top surface where the logs were shaped.

-

∙ An object at least 2.3 m long was placed in the rebates, across the central logs, and four oak stakes were set, two at each end of the object. These stakes would have stopped the object rolling sideways or being moved out of its precise alignment.

-

∙ An oval wattle fence was constructed around the central setting defining, revetting, and/or protecting it.

-

∙ Larger oak trees were felled and brought to be finished on site. These trees may have derived from the same source, and some might even have been the same trees that were used for Holme I.

-

∙ Postholes were excavated at intervals and timbers were set within them to form the inner arc.

-

∙ A trench was excavated and timbers were set edge-to-edge within it to form the eccentric oval outer palisade.

All evidence for the level of the original ground surface at Holme II has been lost to erosion. As a result, it is not possible to say for certain how deep the timbers were originally set into the ground. However, if it is assumed that all above ground elements would have rotted and been lost over 20–30 years and timber below ground would have been preserved by waterlogging, the surviving lengths of the timbers can be used as an indicator of how far they were set into the ground (Table 2). This suggests that the bases of the timbers from the palisade where placed at least 0.65–0.8 m below the surface, whereas those from the inner arc were inserted at least 0.3 m into the ground.

Depth below ground is commonly used to suggest height above ground, with variations in depth taken to represent either variations above ground or the need to get the tops of different length timbers level. If the latter is assumed most likely and a ratio of 1:3 is used (as in Brennand & Taylor Reference Brennand and Taylor2003, 66), the level top of the outer palisade would have stood around 2 m above the ground (based on timber 403), while the inner arc would have been in the region of 0.9/1 m high.

Comparative sites and the use of Holme II

Having proposed a constructional sequence and the height of the timbers, it is necessary to consider why the Holme II timber circle was built and how it was used. One starting point is to assess comparable sites in Britain and north-western Europe. Although no other monument with exactly the same form as Holme II has been discovered, structures dating to the 3rd and 2nd millennia cal bc with outer palisades, inner arcs, inner settings, and central settings are known (Table 10; Figs 20–21).

Fig. 20 Holme II and selected comparable sites (after Alexander et al. Reference Alexander, Ozanne and Ozanne1960, fig. 2; Ashwin & Bates Reference Ashwin and Bates2000, fig. 109; Brennand & Taylor Reference Brennand and Taylor2003, fig. 4; Christie Reference Christie1967, fig. 2; French Reference French1994, fig. 18; Glasbergen Reference Glasbergen1954, fig. 16; Lynch Reference Lynch1993, fig. 7.6; Varley Reference Varley1938; Vyner Reference Vyner1988, fig. 2; White Reference White1969, fig. 3)

Table 10 Selected 3rd and 2nd Millennium bc Sites with Palisades

I palisade height as suggested by excavator

The most obviously comparable outer palisade of edge-to-edge timbers is that at Holme I. However, there do appear to have been a number of differences between the two. Most of the timbers studied at Holme II were tangentially split then trimmed square, whereas nearly all at Holme I were half-split. All but one of the palisade timbers at Holme I had bark attached to their outer surface, but at Holme II it seems that all the bark was removed. With a maximum internal diameter of 6.78 m the Holme I palisade was smaller than Holme II. Although Holme I was interpreted by its excavators as a freestanding timber circle (Brennand & Taylor Reference Brennand and Taylor2003, 7 & 62–72), others have suggested that the palisade may have revetted a burial mound (Gibson Reference Gibson2005, 141–2).

The two alternative interpretations of Holme I reflect the discovery of continuous palisades in varying contexts (Table 10; Figs 20–21). For example, at Letterston I, Letterston II, and Brenig 40 palisades 1 m or less in height revetted the edge of burial mounds. That at Deeping St Nicholas 28 was placed on the edge of an existing mound. A palisade at Brampton and a narrow ring-ditch that could have held a palisade at Arreton Down may have been in similar locations. Closely set timbers are also known to have surrounded many burial mounds in the Netherlands and at least two in Germany (Glasbergen Reference Glasbergen1954 pt II, 17 & 87). In comparison freestanding palisades are known from Bleasdale, Street House, and possibly Harford. At Bleasdale there was a small burial mound in the east of the area enclosed; Street House contained a bank, a stone ring, and a central setting of two posts; and Harford’s possible palisade surrounded a circle of 32 post-holes.

If the ring-ditch at Arreton Down held a palisade, the 43+ stakes placed 0.1–0.35 m inside it would be a comparable inner arc. Variations in the distances that timbers were placed from the outer feature are apparent at both sites, although the distances were less at Arreton Down than at Holme II. Similar, but not directly comparable, to the palisade/inner arc relationship are sites with two closely placed outer rings of stakes, such as Amesbury G71 (Christie Reference Christie1967, 341–2) and Toterfout Halve Mijl 8 (Glasbergen Reference Glasbergen1954 pt I, 53).

Although roughly circular and larger than the inner fence at Holme II, the inner circles at Brenig 40 and 41 are broadly comparable. Both were associated with wickerwork (Lynch Reference Lynch1993, 52–4, 57 & 60–1). Despite lacking evidence for wicker, the inner circle at Amesbury G71 (Christie Reference Christie1967, 340–1) and the oval-shaped setting of stakes under the mound at Toterfout Halve Mijl 8 (Glasbergen Reference Glasbergen1954, part I, 51–3) may also have been similar. Features found within central settings of stakes include graves, such as at Brenig 40, Brenig 41, and Arreton Down, and rectangular mortuary structures (at Brenig 40 and Toterfout Halve Mijl 8). Rectangular mortuary structures are known from beneath at least six burial mounds at Toterfout Halve Mijl (Glasbergen Reference Glasbergen1954, part I, 45, 57, 59, 65, 67 & 78).

This discussion of comparative sites demonstrates that palisades formed parts of monuments interpreted as free standing timber circles and burial mounds, while inner arcs and inner settings tend to be associated with burial mounds. Although no directly comparable central settings are known, features within inner settings include graves and mortuary structures. As most of these four types of feature have been found in association with burials, it is most likely that Holme II was a mortuary monument.

The interpretation of Holme II as a mortuary monument raises the possibility that the two central logs may have supported a body. At 2.3 m the distance between the eastern and western retaining stakes is too long for an unsupported body. Instead it is likely that the rebates in the logs held an object on or in which a body was placed. A stretcher, boat, trough, hollowed-out tree trunk/plank-built coffin, plank, or bier are all possibilities (Brennand & Taylor Reference Brennand and Taylor2003, 12). If the central logs held a coffin, the use of logs in this way could suggest that a hollowed-out tree trunk coffin was used. Remains of Bronze Age hollowed-out tree trunk coffins have been found in graves associated with a number of excavated British burial mounds (Ashbee Reference Ashbee1960, 86–91). In Norfolk they are known from Bawsey and Bowthorpe (Wymer Reference Wymer1996, 1–2, 5–7 & 26; Lawson Reference Lawson1986, 23–30 & 45–7), while those from neighbouring counties include a child’s coffin from Deeping St Nicholas 28 (French Reference French1994, 25 & 100).

The minimum widths of tree trunk coffins from Bawsey, Bowthorpe, and Deeping range between 0.2–0.5 m, with maximum widths between 0.5–0.7 m (Wymer Reference Wymer1996, 5–7; Lawson Reference Lawson1986, 23–30; French Reference French1994, 25). Some (Bawsey, Bowthorpe grave 14, and Deeping) would have been able to fit between the pairs of stakes beside Holme II’s central logs. However, as their lengths range from 1.25–1.95 m, none would have spanned the distance between the two sets of stakes. Longer tree trunk coffins that could have done so are known from further afield, including the boat shaped examples from Loose Howe (2.5–2.7 m; Elgee & Elgee Reference Elgee and Elgee1949) and Gristhorpe, Yorkshire (2.29 m; Melton et al. Reference Melton, Montgomery, Knüsel, Batt, Needham, Parker Pearson, Sheridan, Heron, Horsley, Schmidt, Evans, Carter, Edwards, Hargreaves, Janaway, Lynnerup, Northover, O’Connor, Ogden, Taylor, Wastling and Wilson2010, 805).

Interpreting Holme II as a mortuary structure raises the question of whether a barrow mound formed part of the monument. It is possible that there was no mound, either because it was not part of the design or because the structure’s builders planned to return at a later point and add one but, for some unknown reason, did not. However, it is equally plausible that an attempt was made to conceal the central setting under a burial mound constructed from material quarried from a surrounding ditch or ditches. If a ditch was present at Holme II, it might be reasonable to expect it to be visible as an encircling depression in the surrounding deposits, but to date no such feature has been seen. Alternatively a mound could have been made from sediment stripped from the adjacent area, rather than upcast from ditches.

Where heights for palisades revetting burial mounds have been suggested, they are 1 m or less (Table 10). With a height of around 2 m, the Holme II palisade was perhaps too tall to have been built with the purpose of revetting a mound. Instead, it might be more appropriate to consider the inner arc or the inner fence as mound revetments. Figure 22 explores the second possibility, with a mound formed from sediment stripped from the area within the enclosing palisade.

Fig. 22 Artist’s impression of Holme II, looking west

Treatment of the dead in Bronze Age Britain was not restricted to inhumation burials within barrows – a wide range of practices have been identified (Bradley Reference Bradley2007, 158–68). These include cremation and cremation burial (McKinley Reference McKinley1997), mummification (Booth et al. Reference Booth, Chamberlain and Parker-Pearson2015, 1161–6), multiple burials in single graves (Petersen Reference Petersen1972), burials in natural mounds (Martin Reference Martin1977), and the placing of bodies in wet places (Healey & Housley Reference Healy and Housley1992). Located in a saltmarsh and probably associated with a mound, it is possible that Holme II represents the combination of a number of ways that the dead were treated.

The relationship between Holme I and Holme II

As the timbers used in both Holme I and Holme II were felled at the same time, it is not possible to consider either monument in isolation. Instead they have to be seen as a pair of timber circles. The role of the inverted central tree at Holme I and the differences between the timbers used in the structures are important to any understanding of the relationship between them and speculation on how they may have been used.

The effort involved in felling and transporting a large tree with its stump attached, then placing the once visible part upside down in the ground at Holme I would have been considerable, suggesting that the people who chose to do this had strong reasons for doing so. Individual decisions would have played a part, but structuring beliefs held by the local community would also have been important. Links have been drawn between inversion and death in the Bronze Age (eg, Brennand & Taylor Reference Brennand and Taylor2003, 70–1) and, if inversion did symbolise death, it is possible that the community which pointed the tree downwards may have believed they were directing it towards an underworld of the dead. Some have suggested that the upturned roots of the tree might have served as an excarnation platform (Pryor Reference Pryor2002, 271). If believers in an underworld did place a body amongst the roots they may have done so in a rite of separation, in the belief that the tree would act as a connection to the land of the dead and transport the spirit of the deceased. After a certain period of time – perhaps just that of a particular ceremony – the body could have been removed and buried in a rite of incorporation at Holme II.

The central logs at Holme II and all but one of the palisade timbers at Holme I had bark attached to their outer surfaces. From a distance the palisade would have looked dark and rough, until the timbers began to dry out and the bark began to fall off. In comparison, the central tree at Holme I had all its bark removed (Brennand & Taylor Reference Brennand and Taylor2003, 17) and it appears that the Holme II palisade had little or no bark on its outer surface – it would have looked pale and smooth from a distance (Robertson Reference Robertson2014, appx 1). A number of studies have suggested some monuments were used for ceremonies by the living, while others were perceived as belonging to the dead (eg, Pryor et al. Reference Pryor, French, Crowther, Gurney, Simpson and Taylor1985, 62–4; Parker-Pearson & Ramilisonina Reference Parker-Pearson and Ramilisonina1998; Pryor Reference Pryor2003, 240–5 & 256). Applying this interpretation, it is possible that the bark-covered outer face of Holme I’s palisade and Holme II’s central logs could have symbolised ‘alive’ trees and therefore the living. They may have subsequently ‘died’ when the bark fell off (Taylor Reference Taylor2010, 94–5). In comparison, the barkless outer face of Holme II’s palisade could have been seen as ‘dead’ from the time of construction. The potential presence of symbols relating to life and death in both timber circles demonstrates how difficult it is to understand the beliefs and actions of the community who built them.

Holme I and Holme II in the wider landscape

Although the landscape around the sites of the two timber circles has changed considerably since 2049 bc, it is possible to reconstruct the view from them. Saltmarsh would have stretched in all directions, with sand dunes some distance to the north. There would have been freshwater marshes and woodland to the south, with a range of habitats (including open woodland) on the higher dry ground further south (Brennand & Taylor Reference Brennand and Taylor2003, 44–6, 49–55 & 59). Despite woodland and trees to the south, it is likely that there were clear, open views from the sites of both structures to the east, south, and west. This would have ensured that it was possible to clearly see the sun’s movement from east to west throughout the day.

The likelihood that the sun’s movement could be observed from the sites of the circles raises the possibility that they may have been built with reference to the sun. At Holme I a north-east to south-west alignment was identified based on a forked entrance post and opposing timber 65 which may have referenced the midsummer rising sun (and therefore the midwinter setting sun; Brennand & Taylor Reference Brennand and Taylor2003, 65 & 66–8). The absence of a clear axis of symmetry or alignment in the Holme II palisade and limited excavation makes it impossible to say if there was a similar reference. The use of a timber from a tree at least 350 years old in the south-west of the palisade hints at the possible importance of this section, but the sample of timbers studied is too small to make any firm conclusions. More indicative perhaps is the north-east to south-west orientation of Holme II’s two central logs. The felling of the timbers in spring or summer suggests both circles were built in one of these seasons. Perhaps the central logs were placed in position at midsummer sunrise in 2049 bc?

It is not known where the people who built Holme I and Holme II lived. Although prehistoric flint artefacts have been found in Holme-next-the-Sea parish, few are definitely Bronze Age in date and no clear locational patterns have been identified. The closest evidence for settlement comes from higher land about 3 km to the south-east at Thornham (NHER 1308; Fig. 1). Here 15 small sherds of Late Neolithic/Early Bronze Age (Beaker type) pottery were found during the excavation of a 1st century AD fort (Gregory Reference Gregory1986, 5 & 10). The nearest excavated Late Neolithic/Early Bronze Age settlement is on Redgate Hill about 6 km to the south-west (Healy et al. Reference Healy, Cleal and Kinnes1993; NHER 1396). The lack of known settlements in north-west Norfolk is not surprising given they are difficult to find; few have been recognised in the county (Ashwin Reference Ashwin1996, 47 & 52).

Ring-ditches, probably the remains of levelled Bronze Age burial mounds, have been recorded throughout north-western Norfolk (Lawson Reference Lawson1981, fig. 17; Albone et al. Reference Albone, Massey and Tremlett2007, fig. 5.1). Those closest to the beach are located on rising land, about 2.5 km to the south (NHER 11844 & 12852; Fig. 1). Other nearby examples include two ring-ditches east of Hunstanton Park (NHER 26962 & 29833) and the large dispersed group at Fring (NHER 45008). In 1968 a round barrow was partially excavated at Old Hunstanton, about 6 km to the south-west (Lawson Reference Lawson1986, 108–10; NHER 1263). This may have been contemporary with the nearby settlement on Redgate Hill and a number of ring-ditches visible on aerial photographs. At Titchwell, approximately 4 km to the south-east of Holme Beach, an isolated Bronze Age cremation was discovered during archaeological monitoring (Bush & Diffey Reference Bush and Diffey2011; NHER ENF132412).

The freshwater marsh

The change to freshwater habitats appears to have been associated with at least a partial change in land-use. Mortuary monuments with symbolic meaning were replaced by structures of apparently more utilitarian nature, although the discovery of metal objects suggests that the area may have continued to be a focus for rites.

Trackway NHER 38221 and stake group NHER 38212/38213 are additions to the corpus of Neolithic and Bronze Age timber trackways recorded in many wetland and coastal environments. With brushwood and stakes, trackway NHER 38221 is broadly comparable to brushwood trackways found on the Essex Blackwater (Wilkinson & Murphy Reference Wilkinson and Murphy1995, 143–50) and the Thames at Barking (Meddens Reference Meddens1996, 326–7). The presence of transverse timbers suggests that it could have been a corduroy trackway like those at Meare Heath and Abbots Way in the Somerset Levels (Coles & Orme Reference Coles and Orme1976; Coles & Hibbert Reference Coles and Hibbert1968, 248–51), but not enough survived to be sure of this. Although no brushwood or planks associated with stake group NHER 38212/38213 have been identified, the stakes could have acted as retainers in a brushwood or log trackway. Log trackways were formed from logs laid on the ground surface end-to-end and held in place by stakes, such as at Bermondsey (Thomas & Rackham Reference Thomas and Rackham1996, 238–44 & 249–50).

Trackway NHER 38221 may have been used to access resources, such as an area of coppiced trees of which the stump to the north-east of Holme II was the only surviving remnant. Alternatively it may have provided a routeway from the dry land to the south to dunes and intertidal environments to the north. Although constructed about 1000 years after Holme II, it is possible that a burial mound associated with the timber circle may have been visible from the brushwood trackway to the east.

The discovery of collapsed stands of coppiced timbers is incredibly important. Coppiced timbers and re-used coppice stools have been recorded at a number of Neolithic and Bronze Age sites in the British Isles including Flag Fen (Taylor Reference Taylor2001), Etton in Cambridgeshire (Pryor Reference Pryor1998, 127–59), and the Somerset Levels (Rackham Reference Rackham1977). However, very few in situ coppice stools or collapsed coppiced stems have been reported. In the east of England examples are limited to coppice stools amongst a sinuous trackway at Bradley Fen, Cambridgeshire (Maisie Taylor pers. comm.), and coppiced stools in the ditch of Etton’s Neolithic causewayed enclosure (Pryor Reference Pryor1998, 25, 125, 127 & 129).

Four of the five copper alloy objects (and probably the 5th and the axe-hammer) were found unstratified on the beach surface. As a result, it is difficult to draw conclusions regarding their original deposition. However, their dates and proximity to the peat beds suggest that they fit within the prehistoric tradition of depositing objects in wetland environments (Bradley Reference Bradley2000, 47–63). Another local example of this phenomenon is the hoard of a palstave, two neck rings, a bracelet, and a dress pin found in drained marshland about 3 km to the south-west of the circles (Lawson Reference Lawson1979).

CONCLUSIONS

Following the discovery of Holme I in 1998, archaeological investigations on Holme beach have revealed two Bronze Age timber circles, trackway/s, coppiced trees, and deposited metal objects. The construction of structures and activity within salt- and freshwater marsh habitats in the Bronze Age and continuous waterlogging preserved evidence that rarely survives at dry land sites: timbers, evidence for woodworking, and wood suitable for dendrochronological and radiocarbon dating. Without this particular set of circumstances and 16 years of work in a challenging intertidal environment, a considerable amount of significant information would have been lost.

Monitoring – both formal and informal – made it possible to use dendrochronology to date the felling of the trees used to build Holme II. The discovery that this took place in the spring or summer of 2049 bc, precisely the same time as the tree felling for Holme I happened, poses many questions. Holme I and II now have to be seen as paired timber circles and represent the first known case of two monuments being built together in British prehistory.

Comparisons between Holme II and other timber circles suggest that it was probably a mortuary monument. It is possible that a body was placed in a coffin or another object close to the centre of the circle and then a burial mound was constructed over the top. The shared date allows speculation about how Holme I and Holme II worked together – one could have been used for rites of separation, while burial at the other served as a rite of incorporation.

Although the shape, form, and interpretation of Holme II are important to the study of British timber circles, it is the evidence provided by the waterlogged timbers that is of greatest significance. Not only does this demonstrate that different types of timber – logs, split timbers, posts, and wattle of varying sizes and heights – could be used in a single monument, but the dating of both Holme I and II to the same season/s of the same year opens up the possibility that other Bronze Age monuments built close together could have been constructed at the same time. We can only hope that future discoveries of waterlogged timber circles elsewhere in Britain equally further our knowledge and understanding.

Acknowledgments

Sincere thanks are due to the Norfolk Wildlife Trust and the Le Strange Estate for their support for all fieldwork and research since 1998. Particular thanks are due to Gary Hibberd, Bill Boyd (both Norfolk Wildlife Trust), and Michael Meakin (Le Strange Estate).

Fieldwork and research since 1998 has been funded by English Heritage. The 2003 walkover and monitoring project were funded under the Historic Environment Enabling Programme, with the dendrochronology and production of this article supported under the National Heritage Protection Commissions Programme. Particular thanks are due to Kath Buxton, Kim Stabler, Matthew Whitfield, Peter Marshall, Alex Bayliss, Derek Hamilton, John Meadows, and Tim Cromack.

The walkover and monitoring surveys were carried out by the NAU (now NPS Archaeology) on behalf of Norfolk Landscape Archaeology (now Norfolk County Council Historic Environment Service). Dendrochronological fieldwork was undertaken by the Historic Environment Service and freelance specialists. John Ames, Ian Tyers, Maisie Taylor, Cathy Tyers, Andrew Hutcheson, Bill Boismier, David Adams, Peter Crawley, Fran Green, Adam Barker, Andy Barnett, Maggie Foottit, Steve Morgan, Sandrine Whitmore, James Albone, Mercedes Langham-Lopez, Charlotte Veysey, and the author worked on site. Specialists included Ian Tyers, Maisie Taylor, Cathy Tyers, Lucy Talbot, Sarah Percival, Julie Curl, Val Fryer, Derek Hamilton, Peter Marshall, Gordon Cook, Andrew Rogerson, Alan West, Katie Hinds, and Erica Darch. The majority of the illustrations were prepared by David Dobson (NPS Archaeology). The exceptions are Figures 4 and 12–13 by Peter Marshall, Figure 11 by Ian Tyers, and Figure 19 by Jason Gibbons.

John Lorimer, local archaeologist and reporter of Holme I, has always been willing to share his time, discoveries, and archive. Since 2003 support and advice has been kindly provided by Bill Boismier, Ken Hamilton, Andrew Hutcheson, Maisie Taylor, Ian Tyers, Jayne Bown, James Albone, David Gurney, Kelly Gibbons, Mark Brennand, Peter Murphy, Will Fletcher, Zoe Outram, Francis Pryor, Alex Gibson, Michael Bamforth, Tim Holt-Wilson, William Parsons, Suzanne Robertson, and anonymous referees, amongst others. Peter Lambley and John Ebbage of English Nature/Natural England provided SSSI permissions. Access to resources was provided by staff of the University of East Anglia Library, University Library Cambridge, and the Haddon Library Cambridge.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/ppr.2016.3