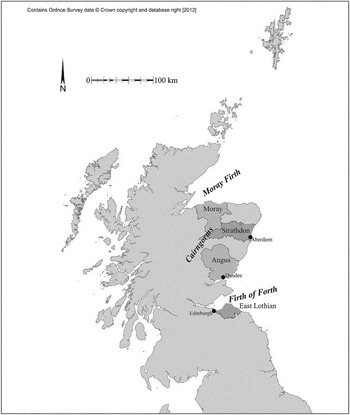

The arcing crescent around the Mounth (the eastern edge of the Grampians) between the area of the Firth of Forth to the Moray Firth (Fig. 1) has long been recognised as a distinct archaeological zone (Piggott Reference Piggott1966). The area includes regionally distinctive Iron Age and early medieval data sets and monument types including oblong gateless hillforts with timber-laced ramparts (Feachem Reference Feachem1966, 66–7), hoarding (Hunter Reference Hunter1997), massive metalwork (Hunter Reference Hunter2006), and Pictish symbol stones (Henderson & Henderson Reference Henderson and Henderson2004). The northern portion of this zone, from the Mounth to the Moray Firth; north-east of Scotland, also has regionally specific monuments from earlier periods, for example recumbent stone circles (Bradley Reference Bradley2005; Welfare Reference Welfare2011). However, while archaeological research in Aberdeenshire started in the 18th century (eg, Williams Reference Williams1777), until very recently it has suffered from both a lack of research (Ralston et al. Reference Ralston, Sabine and Watt1983, 149; Harding Reference Harding2004, 84) and the full publication of the work that has taken place (eg, Kirk Reference Kirk1958; Small & Cottam Reference Small and Cottam1972; Greig Reference Greig1972; Ralston Reference Ralston1980). As a consequence the later prehistoric and early medieval (1800 bc–ad 1000) settlement record of this area has been ill served by archaeology and the area has been generally ignored in synthetic works such as those by Alcock (Reference Alcock2003, 8), Hill (Reference Hill1995), Cunliffe (Reference Cunliffe2005, 599), Bradley (Reference Bradley2007, 261), and Driscoll (Reference Driscoll2011, 264–6) that portray the area as a blank. This is, in part, because of a lack of evidence (eg, Haselgrove et al. Reference Haselgrove, Armit, Champion, Gwilt, Hill, Hunter and Woodward2001, 25, 86), however, as will be demonstrated, evidence from the wider area has been poorly disseminated and has failed to impact on assessments of the periods in question at the broader level of the British Isles.

Fig. 1 Location of Strathdon and comparator zones (Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2012)

This article will first present a brief outline of the history of research from the 18th century to the 2007 publication of the Royal Commission on Ancient and Historic Monuments of Scotland's (RCAHMS 2007) study: In the Shadow of Bennachie. This is followed by a précis of recent research into settlement sequences, the evidence from which will then be placed in a Scottish context, before then being used to explore the factors behind enclosure.

While the end date of this study (ad 1000) may strike the reader as inappropriate for a prehistoric journal, it is argued that this date marks the appearance of substantial historical records in Scotland and the true end of the ‘prehistoric’ period (Parker Pearson & Sharples Reference Parker Pearson and Sharples1999, 359; Edwards & Ralston Reference Edwards and Ralston2003). This extended study period also allows for a genuine view of settlement patterns in the study area over the longue durée.

Explicitly, following Cunliffe (Reference Cunliffe2005, 347) and Armit (Reference Armit2007, 25), the term ‘hillfort’ is used as a portmanteau term to described enclosed sites of various sizes, in different locations.

History of Research

Despite the historical issues with research and publication in Aberdeenshire there has been a recent upsurge of rescue and research work, which have reviewed the artefact record of the region (eg, Hunter Reference Hunter2007b; Heald Reference Heald2011; Campbell Reference Campbell2007), the historical record (Woolf Reference Woolf2007; Fraser Reference Fraser2009), key backlog excavations (Ralston & Sabine Reference Ralston and Sabine2000; Armit et al. Reference Armit, Schutling, Knusel and Shepherd2011) and the field archaeology of the Don valley system, called hereafter Strathdon (RCAHMS 2007). Of particular significance to this paper is the series of rescue excavations covering 50 ha which were undertaken at Kintore (Fig. 2) in 1996–2006 (see Cook & Dunbar Reference Cook and Dunbar2008 for a précis), in advance of an infrastructure and housing development. This was part of a wave of similar, if smaller; mitigation exercises undertaken across the north-east (see Cressey & Anderson Reference Cressey and Anderson2011 for a summary).

Fig. 2 Detailed plan of study area (Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2012)

The excavated sequence from Kintore ran from the Neolithic to the medieval period and included a Roman marching camp. The unenclosed later prehistoric sequence included c. 50 round-houses, followed by a series of early medieval unenclosed structures (Cook & Dunbar Reference Cook and Dunbar2008). While such a scale of excavation and accompanying sequences are now relatively common elsewhere in the UK (eg, Lewis et al. Reference Lewis, Leivers, Brown, Smith, Cramp, Mepham and Phillpotts2010), the works at Kintore are at present unique in Scotland. However, the region's hillforts have remained excluded from this period of mitigation excavation. The RCAHMS field survey of Strathdon (2007), grouped the area's 20 or so hillforts and enclosures into a six-fold classification based on size and type of defence (ibid., 100–1). This was in fact the third detailed review, following Feachem (Reference Feachem1966), and Ralston (et al. Reference Ralston, Sabine and Watt1983), each of which came up with different conclusions, none of which was based on excavation.

Settlement Sequence

The settlement record for Scotland north of the Forth is interpreted as being dominated by unenclosed structures in the later prehistoric and early medieval periods (Macinnes Reference Macinnes1982; Alcock Reference Alcock1988). However, this model was based on very little excavation (Davis Reference Davis2007). In fact, prior to the year 2000, substantial excavated unenclosed settlements were rare and tended to derive from development of upland sites (Pope Reference Pope2003, 421–2), Dalladies (Kincardineshire) and Douglasmuir (Angus) represented two of the few unenclosed lowland settlements (Watkins Reference Watkins1980; Kendrick Reference Kendrick1995) with nine and seven round-houses respectively. Kirk's work in the Sands of Forvie (Aberdeenshire) appears to have identified 19 round-houses (1958), though they were neither fully recorded nor reported upon (Ralston & Sabine Reference Ralston and Sabine2000). However, the existing evidence indicates that in Scotland round-houses were constructed over a long period between c. 1800 bc and c. ad 500 (Crone Reference Crone2000; Ashmore Reference Ashmore2001; Pope Reference Pope2003).

With regard to early medieval settlement, there are in fact no firmly dated unenclosed settlement sites from the Firth of Forth to the Moray Firth between c. ad 250 and 550 (Ralston Reference Ralston1997). There are post-souterrain structures at Carlungie and Ardestie (Angus; Wainwright Reference Wainwright1955, 92; Reference Wainwright1963), the occasional radiocarbon date, for example, Dalladies 2 (Fettercairn; Watkins Reference Watkins1980, 164), but well dated formal structures like those at Easter Kinnear (Fife; Driscoll Reference Driscoll1997) or the Pitcarmick (Perthshire) series (Harding Reference Harding2004, 240–3) date to after ad 500.

Excavation in and around Kintore between 1999 and 2010 recorded in excess of 70 unenclosed structures dating from c. 1800 bc–ad 250 (Alexander Reference Alexander2000; Johnson Reference Johnson2004; Murray & Murray Reference Murray and Murray2006; White & Richardson Reference White and Richardson2010; Reference Cook, Dunbar and HeawoodCook et al. forthcoming), representing the largest regional assemblage of round-houses ever excavated in Scotland by a significant factor (Pope Reference Pope2003, 421–2). It is not clear if the absence of round-houses after ad 250 represents a real gap or simply one in the evidence but it is echoed elsewhere in Scotland north of the Forth (Hunter Reference Hunter2007a, 49; see also Armit et al. Reference Armit, Schutling, Knusel and Shepherd2011).

There are three Roman marching camps in Strathdon (RCAHMS 2007, 111–14) and excavation at Kintore revealed at least two phases of Roman occupation: one in the late 1st century and one in either the late 2nd or early 3rd century. In addition, there was a series of late dates from pits and ovens that bridge the above-mentioned gap in the settlement record (Alexander Reference Alexander2000, 64; Cook & Dunbar Reference Cook and Dunbar2008, 33). These may represent the remains of highly truncated structures but, given the nature of the site and in the opinion of the excavator, it seems more likely that they indicate a transient, less permanent system of occupation. It may well be that more structured settlement exists within the various cropmark sites (RCAHMS 2007, 94) but at present these remain untested. A subsequent genuine gap in the unenclosed sequence until the 7th–10th centuries ad reflects the wider pattern (see above), when unenclosed rectilinear structures, associated with underground storage, and corn-drying kilns appear (Cook & Dunbar Reference Cook and Dunbar2008, 149–50 and see below).

Beyond Strathdon, but still in the north-east, important new evidence has been produced from Culduthel, Birnie, and Seafield (Murray Reference Murray2007; Hunter Reference Hunter2007a; Cressey & Anderson Reference Cressey and Anderson2011). These sites have significant Late Iron Age sequences (though none extends beyond c. ad 250), including metalworking, imported goods, and two Roman coin hoards. Intriguingly, research by Hunter (Reference Hunter2007a, 49) indicates that there is a break in Roman imports after ad 250, which he links to a deliberate policy of withdrawal of Roman support in an attempt to destabilise local polities (ibid.).

The absence of coherent settlement structures extends across the 4th century conflicts between ‘Picts’ and the Roman provinces in southern Britain (Fraser Reference Fraser2009, 50–1). The 4th century Friotzheim dice tower appears to record a Roman victory against the Picts (Hall Reference Hall2007, 3). The scale and extent of these conflicts are unknown, although the Barbarian Conspiracy of ad 367 involved the Verturiones, who are now argued by Fraser to be located north of the Mounth near Inverness, rather than to its south as traditionally proposed (Fraser Reference Fraser2009, 50–1). It is possible to suggest that the Verturionian sphere of influence anticipated that of the early medieval kingdom of Fortriu, which saw an expansion of power in the late 7th century, involving attacks on the enclosed site at Dunottar, Stonehaven (Fraser Reference Fraser2009, 214). All of these campaigns would by necessity have involved crossing Strathdon.

In addition, despite the apparent absence of coherent unenclosed settlement, there is clearly some form of population and activity in the area as there are both Class I Pictish symbol stones (Foster Reference Foster2004, 70–1; Henderson & Henderson Reference Henderson and Henderson2004) and a series of hoards in Aberdeenshire (Heald Reference Heald2001). Fraser and Halliday (Reference Fraser and Halliday2011) have argued that Class I symbol stones are located at prominent positions along parish boundaries which appear to reflect older boundaries.

The environmental record is poorly understood and there have been very few pollen cores undertaken from the north-east (RCAHMS 2008, 25–43); the available evidence has been stretched from other areas to cover this zone. For example, it is not clear what impact if any the putative Late Bronze Age climatic deterioration (Ashmore Reference Ashmore1996, 113–18; Cowie & Shepherd Reference Cowie and Shepherd2003, 165–7) had on the north-east and, indeed, its impact is disputed elsewhere (Tipping Reference Tipping2002; Bradley Reference Bradley2007, 179). Others have linked this event to the appearance of enclosure and the abandonment of marginal uplands (Thomas Reference Thomas1997).

During the closing centuries bc there is pollen evidence from south-east Scotland for increased woodland clearance and agricultural intensification (Tipping Reference Tipping1994, 31–3). This was combined with the wider adoption of the rotary quern in the second half of the 1st millennium bc across Scotland (McLaren & Hunter Reference McLaren and Hunter2008). In the same period there is evidence from Dubton, Angus and Lairg (Sutherland) for expansion onto more marginal ground (Church Reference Church2002; McCullagh & Tipping Reference McCullagh and Tipping1998), with the latter made possible by the introduction of iron ploughs (ibid., 211). These various factors are taken to indicate that there may have been an agricultural surplus produced in the second half of the 1st millennium bc and certainly in the closing centuries, and that this could well have included Strathdon.

Table 1 identifies the main trends in Strathdon unenclosed settlement and the various factors measured from it. The periods used follow the Kintore excavation (Cook & Dunbar Reference Cook and Dunbar2008, 25), with the Late Iron Age sub-divided around ad 250. Here ‘Pits’ refers to the excavation of pits within the interior of the structure, which Brück has argued may have been dug at key points in the inhabitants’ lifecycle (Reference Brück1999). While this may be conjecture there are clear chronological patterns in the numbers of pits present within round-house interiors of the Kintore structures (Cook & Dunbar Reference Cook and Dunbar2008, 347–6; 356–7). The process of ‘ritual enrichment’ described by LaMotta and Schiffer (Reference LaMotta and Schiffer1999), takes place near the end of active use of a round-house, prior to abandonment, where material is placed within it. This could represent the abandonment of large bulky or broken items, the dumping of rubbish from neighbouring settlements, or the deliberate deposition of material of perceived ritual significance. Within Strathdon this takes place in Bronze Age structures but not Iron Age or early medieval ones, which contain very few finds. Finally, ‘external feature’ relates to contemporaneous features relating to activity taking place externally to the structure, for example corn-dying kilns or furnaces.

Table 1 unenclosed settlement pattern in Strathdon

This evidence points to a number of trends. Most of the sequence is represented by isolated structures: only two periods show clusters of either settlement or external features: Middle Iron Age and Early Medieval b. In the Middle Iron Age the putative agricultural surplus of the closing centuries bc (see above) may have led to population growth and emergence of a more complex society (Cook & Dunbar Reference Cook and Dunbar2008, 347–6). The same process may be tentatively suggested for the Early Medieval b period, from the appearance of corn-kilns and underground storage areas which hint at the large scale storage of agricultural produce (ibid., 356–7). Pits within round-houses tend to be Bronze Age; in the Iron Age they appear outside structure, for example in pit alignments, which Cook and Dunbar (Reference Cook and Dunbar2008, 364) argue reflects a change of focus for ritual activity from the household to more public arenas. Ritual enrichment occurs in the Bronze Age but not the Iron Age, when structures contain virtually no artefacts at all. This represents a considerable change given the volume of material deposited in Bronze Age structures and may again suggest that deposition shifted to open air locations (Hunter Reference Hunter1997).

Destruction by fire is a constant feature, and it is not clear if this was by accident or design; if by design one could argue for it being part of the closure process at the abandonment of the house, or perhaps even as a result of conflict.

Entrance orientation varies within the round-house assemblage with a hint of an anticlockwise movement over time, though in addition, during the Middle and Late Iron Age at Kintore, only structures with ring-ditches and/or an erosional hollow within the interior (Cook & Dunbar Reference Cook and Dunbar2008, 12–13; Harding Reference Harding2009, 76–81) have north-west facing entrances; all the others (post-ring) face south-east. It has been argued that this may reflect variety in function or status (ibid., 340–1). Certainly in north-eastern Scotland the erosional hollow tends to be focused in the northern or north-eastern sector of the round-house interior. Furthermore, within the Kintore sequence the position of the ring-ditch relative to the internal post-ring also changes: in Middle and Late Bronze Age houses it lies within the post-ring while in Iron Age round-houses it lies outside it (ibid., 331–333).

As stated above, hillforts were excluded from this research. In the absence of any direct dating a variety of models was explored for their construction and date including an early medieval origin (Ralston Reference Ralston1987); whether they had ceased to be built prior to the Roman invasions (Hanson & Maxwell Reference Hanson and Maxwell1983, 12–14) or abandoned before completion in the face of invasion (Shepherd & Ralston Reference Shepherd and Ralston1979, 20); and whether some were contemporaneous with the invasions (Fraser Reference Fraser2005, 40). However, in general, the Strathdon sites were assumed to be Iron Age (Armit & Ralston Reference Armit and Ralston2003, 172–8) and were ignored in early medieval synopses (Alcock Reference Alcock1988). This interpretation was supported by the absence of both early medieval imported goods (Campbell Reference Campbell2007) and non-ferrous metalworking (Heald Reference Heald2011). Beyond Strathdon early medieval hillforts were rare, located on the coast, and associated with elite (or royal) settlement in a hierarchical pattern and in use in the late 4th–early 9th centuries, before being abandoned in favour of unenclosed high status sites (Fraser Reference Fraser2009, 366).

Approach

In order to link the hillforts to the unenclosed sequence the author examined one site from each of the RCAHMS’ six fold classification using key-hole excavation techniques (eg, Alcock & Alcock Reference Alcock and Alcock1992). Such an approach minimises costs by restricting the level of fieldwork and thus the resultant post-excavation and reporting entailments. The research strategy was boiled down to a single question: to when do the enclosing works date? Key-hole trenches focused on ditches and ramparts, entrances were avoided, and excavation was minimised wherever possible. Taphonomically secure charcoal samples were recovered and dated to provide a framework for enclosure of an individual site. While the key-hole approach is not without its criticism (eg, Clarke Reference Clarke2001) and problems since it dates individual events in a complex site rather than establishing an overall sequence, the explicit aim of the project was to provide a structured contribution to a narrative of the role of enclosure in 1st millennia societies in north-east Scotland. Having established such a narrative structure this permits more complex questions regarding chronology and function to be asked by future researchers and for the model to be tested.Footnote 1

Hillforts of Strathdon Archaeological Background

While specific hillforts in Strathdon had been subject to repeated survey and comment, even back to the 18th century (Williams Reference Williams1777), none had been subject to any modern excavation. The RCAHMS volume placed 18 forts and one cropmark enclosure in the scheme outlined below, although the order has no chronological significance (2007, 100–1; Fig. 2). A 20th site, Mither Tap, Bennachie was not included in this scheme. The sites are focused on the northern and eastern edge of the Bennachie range of hills, although one (Barmkyn of North Keig) is on the southern side of this range. This may indicate that the sites are connected to the main routes north–south and east–west around the hill range rather those going into it. However, this distribution may also be connected with the quality of the soils which predominantly belong to the Insch Association, being amongst the most fertile in Aberdeenshire (Glentworth Reference Glentworth1963, 43–4). The same parcel of land also contains the densest concentration of both Neolithic and early medieval sites and artefacts in the region (RCAHMS 2007, 75, 118).

The classification system can be summarised as follows:

• Type 1: oblong forts (Dunnideer and Tap o'Noth inner fort);

• Type 2: multivallate forts (Barra Hill and Barmekin of Echt);

• Type 3: large forts (Dunnideer outer enclosure, Bruce's Camp, and Tillymuick);

• Type 4: very large enclosures (Hill of Newleslie and outer fort at Tap o'Noth);

• Type 5: small enclosures (Wheedlemont, Maiden Castle outer enclosure, and Barflat).

• Type 6: small thick stone walled enclosures (Cairnmore, Barmkyn of North Keig, White Hill, Hill of Keir, and Maiden Castle inner enclosure).

Two modifications are offered to this scheme. Both Type 2 hillforts, Hill of Barra and Barmekin of Echt have two phases (RCAHMS 2007, 98–99); Type 2a is therefore proposed to describe the outer multivallate fort with multiple entrances and Type 2b to define the second phase: a univallate fort with a single entrance, but within Type 2a.

The second qualification is more contentious. The Type 6 enclosures include two forms: those that could just be (but were not necessarily) roofed (Maiden Castle inner enclosure, Hill of Keir, and White Hill) and those that could not be (Cairnmore and Barmkyn of North Keig). A similar argument has been advanced in Argyll by Harding (Reference Harding1984) who argued that the ‘dun’ grouping (RCAHMS 1971, 18) homogenised sites that could be roofed and those that could not be and that this could well mask chronological or functional differences. Thus the author proposes for Strathdon that Type 6a represents small, potentially roofable structures and 6b larger, non-roofed ones.

The precise dating of small, roofable circular stone structures is unclear, since though many have clear Late Iron Age origins and are argued to be cognate forms with brochs, they frequently display early medieval reuse (Harding Reference Harding1984; Armit Reference Armit1990, 55–9; Taylor Reference Taylor1990), leading to considerable debate as to whether some may be de novo early medieval constructions (Alcock Reference Alcock2003, 186–90). As will be demonstrated, evidence from Maiden Castle, Insch (Cook Reference Cook2011a) supports this latter contention.

The oblong forts, Dunnideer and Tap o'Noth, are part of the series first identified by Feachem (Reference Feachem1966, 67, fig. 5). They are rectangular, with massive stone timber-laced ramparts, frequently vitrified, without obvious entrances, often on prominent hilltops, and most commonly found between the Firth of Forth and the Moray Firth in two discrete clusters: the first at Angus, Perthshire, and North Fife and the second around Inverness (Fig. 3). While the massive walls of these forts and the apparent absence of entrances lends them the air of impregnable fortresses, others have suggested non-defensive ceremonial functions, with parallels to both European Viererckschanzen and the Banqueting Hall at Tara (Harding Reference Harding2004, 87). One of the more famous examples, Finavon (Alexander Reference Alexander2002), derives from a ‘nemeton’ place-name (Watson Reference Watson1926, 250), which has been linked to ritual locations in accounts of ‘Celtic’ religion (Ross Reference Ross1974, 62–3), although this appears to be the only such example. In addition, it is increasingly clear that Viererckschanzen are far more complex than previously suggested and many are likely to be normal settlements (Von Nicola Reference Von Nicola2009). In the absence of modern excavation within the interior of an oblong fort, it is more prudent to avoid detailed discussions of their functions. Their precise date has also been subject to vigorous debate (Alexander Reference Alexander2002; Cook Reference Cook2010b): recent archaeomagnetic and radiocarbon dating suggests that they were destroyed in the closing centuries cal bc (Gentles Reference Gentles1993; Ralston Reference Ralston2006, 151), perhaps with a floruit centred around 250 bc (Cook Reference Cook2010b).

Fig. 3 Distribution of oblong forts across Scotland (after Feachem Reference Feachem1966 & Ralston et al. Reference Ralston, Sabine and Watt1983) (Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2012)

These massive ramparts represent a substantial investment of resources (timber and stone) as well as effort. Their subsequent vitrification, a process by which stones are fused together at temperatures in excess of 1000°C (Ralston Reference Ralston2006, 146), represents an even more impressive investment (Ralston Reference Ralston1986). Vitrification requires timber-laced ramparts and involves substantial quantities of fuel over an extended period of time; it is argued that the level of vitrification present on Dunnideer and Tap o'Noth would take days, if not weeks, to achieve (Ralston Reference Ralston2006, 163). The resulting smoke during the day would be seen from far and wide, while the fire at night would be seen over an even further distance, creating a stunning display. Ralston (ibid.) has argued that those sites with vitrification around their entire circuit (eg, Dunnideer and Tap-o'Noth) may have required two phases of firing, given prevailing winds.

Vitrification has no chronological or geographical significance and occurs across Europe (Ralston Reference Ralston2006, 143–63). At present there are no vitrified structures in England or Wales but the process is likely to be related to the slaked (limestone) ramparts of the Welsh Marches (Cunliffe Reference Cunliffe2005, 636; Moore Reference Moore2006, 63). Several models behind vitrification have been discussed: accidental fire, constructional factors (a deliberate act undertaken to strengthen the rampart), and a deliberate act of destruction (Mackie Reference MacKie1976; Ralston Reference Ralston2006, 162–3). Accidental fires would be unlikely to have such sustained effects and the unpredictability of the process suggests it was not constructional (ibid.). Given the inherent difficulties of achieving vitrification, the current totals presumably represent an underestimate of the number of forts fired, the majority reaching insufficient temperature to vitrify sufficient material for it to be observable.

Current views tend to see vitrification as either an act of aggression following capture (Armit Reference Armit1997, 59; Ralston Reference Ralston2006, 163) or as ‘ritual closure’ at the end of the site's active life (Armit Reference Armit2005, 52–3; Moore Reference Moore2006, 63), akin to the destruction of many Neolithic ritual monuments (Noble Reference Noble2006, 45–70), or as argued for the Kintore unenclosed round-houses (see above; Cook & Dunbar Reference Cook and Dunbar2008, 342–3).

In addition to the hillforts, Strathdon also contains over 60 cropmark enclosures. The RCAHMS (2007, 93–4) mapped a range of sizes but made no attempt to further classify them. Some are the ploughed equivalents to some of the hillfort types. For example, Barflat, a small multivallate enclosure (ibid., 100) is similar to the Type 5 enclosures at Wheedlemont and Maiden Castle, while others (c.39, ibid.) appear to be single large round-houses set within enclosures, and there are clearly a number of more substantial enclosures. However, without excavation, it is impossible to comment further.

Results

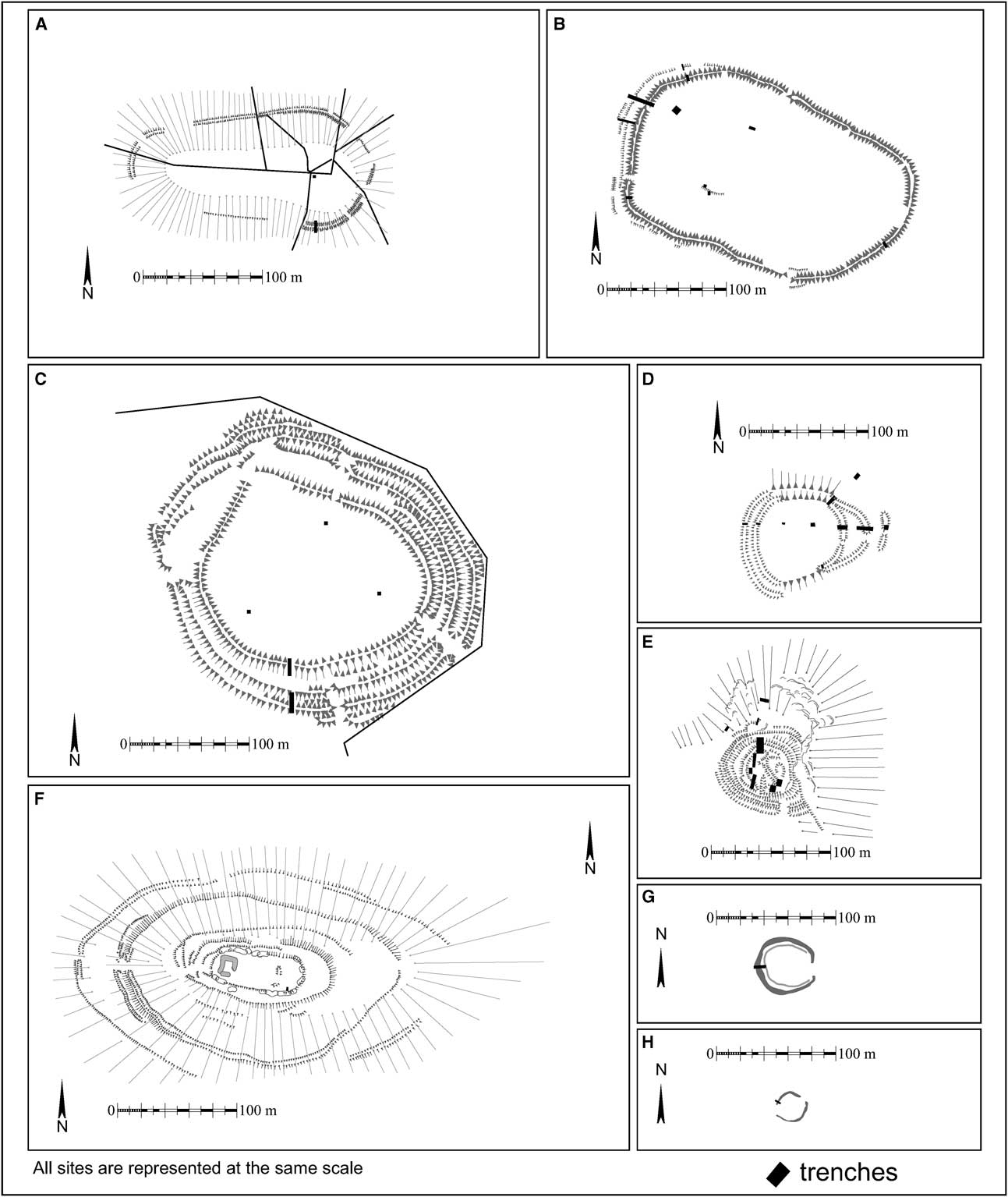

Six sites (Fig. 4), representing the different classes within the revised RCAHMS hillfort scheme, were sampled and are described below. Of these, five were successfully dated. It should be noted that the reasons for selecting these sites over others were entirely pragmatic, ie, ease of access, landowner willingness, etc. In addition, within the immediate environs of Kintore and the unenclosed round-house sequence, were two cropmark enclosures: Wester Fintray and Suttie (RCAHMS 2007, 94), which were also sampled. Two other relevant sites were also subject to excavation: Mither Tap, Bennachie (Atkinson Reference Atkinson2007) and Barflat, Rhynie (Noble & Gondek Reference Noble and Gondek2010; Reference Noble and Gondek2011). The detailed results have been published elsewhere (see Cook Reference Cook2011b for a précis) and only the key results are summarised here (Table 2).Footnote 2Table 3 presents an extrapolation of the excavation results across the RCAHMS scheme.

Fig. 4 Plans of sampled sites. A: Hill of Newleslie; B: Bruce's Camp; C: Hill of Barra; D: Cairnmore; E: Maiden Castle; F: Dunnideer; G: Suttie; H: Wester Fintray (Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2012)

Table 2 Radiocarbon dates from sampled sites

Table 3 extrapolated evidence across RCAHMS scheme

The most obvious trend is that the predominant settlement type in the north-east is unenclosed; the 20 or so hillforts in the sample area derive from a c. 3000 years period. There are also large areas of Strathdon without any hillforts (Fig. 2) although there is no absence of suitable hills. It seems unlikely that many examples have been destroyed elsewhere, as agricultural improvements has tended to avoid hilltops (Bruce Mann pers. comm.).

The dated hillforts cluster into two broad periods: the Early–Middle Iron Age and the early medieval period (Fig. 5). Hill of Newleslie, the outer enclosures of Tap o'Noth, Hill of Barra, and Barmekin of Echt, remain undated. The first two are argued to be Late Bronze Age by comparison with other large hilltop enclosures, such as Eildon Hill North in the Scottish Borders (Rideout et al. Reference Rideout, Owe and Halpin1992, 62–3) and Traprain Law, East Lothian (Armit et al. Reference Armit, Dunwell and Hunter2002; though see Sharples, Reference Sharples2011 for a contra argument). Evidence for the other two is based on comparison with the Brown and White Caterthuns in Angus (Dunwell & Strachan Reference Dunwell and Strachan2007).

Fig. 5 Extrapolated distribution of hillforts over time (Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2012)

It is also apparent that, while the majority of sites have some level of earlier enclosing works, most of the hillforts are apparently de novo locations and only four (Tap o’ Noth, Dunnideer, Hill of Barra, and Barmekin of Echt) are located within earlier enclosures, although this number might increase with further excavation.

The Early/Middle Iron Age evidence indicates the following sequence of dated events:

• Hill of Barra inner enclosure: constructed before 560–360 cal bc

• Bruce's Camp fired after 410–340 cal bc

• Dunnideer fired between 390 and 257 cal bc, and most likely towards the latter end of that range, as well as being probably constructed in the same period but after the outer Type 3 hillfort

• Wester Fintray constructed before 320–200 cal bc

• Suttie constructed before 370–90 cal bc

It is difficult to establish a definitive chronology within the sample. In specific cases the stratigraphic sequence helps. For example, the Dunnideer inner enclosure was constructed after the outer enclosure (Type 3) and thus, by extrapolation, Bruce's Camp (also a Type 3) is likely to be earlier than Dunnideer. However, how does the Hill of Barra inner enclosure (constructed before 560–360 cal bc) relate to Bruce's Camp (destroyed by fire after 410–340 cal bc) as the dates overlap so the sites could be contemporaneous? And how do they both relate to the two cropmark enclosures? At present none of the sites can be confidently dated to the final two centuries bc and the bulk of radiocarbon dates are focused between c. 600 and 200 cal bc. It is further agued that this represents a sequence rather than a cluster of contemporary sites.

This appears to suggest a move from a variety of forms and sizes of hillfort and enclosure to a single form: the oblong fort, although the possibility exists that the cropmark enclosures at Wester Fintray and Suttie were contemporaneous or later. However, despite the lack of internal evidence, it may be more appropriate to see these as part and parcel of the increasing complexity of unenclosed settlement at Kintore, perhaps even as elite residences.

The change in hillfort design encompasses a move from multiple entrances (Hill of Barra outer) to single entrances (Hill of Barra inner; Bruce's Camp) to no entrances (Dunnideer oblong enclosure). In addition, the enclosing works become generally more substantial (Hill of Barra outer to Dunnideer); more regular in size around their circuit (Hill of Barra and Bruce's Camp are at their largest at the entrances while Dunnideer and Tap o'Noth are a regular size), and timber-lacing is introduced into their construction (Bruce's Camp and Dunnideer). It might be argued that timber-lacing itself produces larger and more evenly constructed ramparts but this was not the case at Bruce's Camp. Finally, the latest hillforts (Dunnideer inner and Tap o'Noth inner) have the smallest internal areas.

The number of potential early medieval sites (9) is surprising and a dramatic change from the current interpretation (Cook Reference Cook2011b). However, the dating evidence is more equivocal as there is less scope for stratigraphic relationships than for the prehistoric sites. Moreover it is not clear if these represent successive or contemporaneous sites. The bulk of the radiocarbon dates cluster around cal ad 380–650, with later activity at Mither Tap dated to cal ad 640–780.

It is assumed that these sites are all roughly contemporaneous and, on this basis, there are three types; large or impressive ones (Hill of Barra and Mither Tap), medium-sized (Cairnmore, Wheedlemont, and Maiden Castle outer), and small (Maiden Castle inner enclosure, Hill of Keir, and White Hill). Precisely how such sites relate to each other is unclear but it seems likely that there was some form of hierarchical relationship, given the nature of contemporary society (Alcock Reference Alcock2003, 31–46; Foster Reference Foster1998; 2004). One might assume that the larger or more impressive sites performed the role of a caput, with smaller sites acting as estates, along the lines proposed by Driscoll (Reference Driscoll1991). However, to date, all the rich material culture one might associate with a caput, such as metalworking or high status goods, as found at Burghead (Moray) and Dunadd (Argyll; Edwards & Ralston Reference Edwards and Ralston1978; Lane & Campbell Reference Lane and Campbell2000) is located at the smaller sites such as Maiden Castle, Ryhnie, and Cairnmore. However, this might simply be a product of limited excavation and the possibility of recycling of high status goods to lower status sites should not be forgotten (Crone & Campbell Reference Crone and Campbell2005, 84). Alternatively, it may be that the scale of this putative territory is wrong: perhaps Burghead (the largest enclosure in early medieval Scotland; Alcock Reference Alcock2003, 192–7) was the Royal caput with the Strathdon sites reflecting three layers of regional and local centres.

In addition, there are two foci for the distribution: Rhynie and Inverurie. Each cluster is also associated with a group of Class I Pictish symbol stones (RCAHMS 2007, 124); there are eight stones around Rhynie, including the famous Rhynie Man (Shepherd & Shepherd Reference Shepherd and Shepherd1978) and a more disparate nine between the southern edge of Inverurie and Kintore, many of which appear to be close to their point of origin (Fraser & Halliday Reference Fraser and Halliday2011, 315). The two clusters are also loosely focused on the two most prominent hills in Aberdeenshire: Mither Tap, Bennachie and Tap o'Noth.

Strathdon in Context

This section will attempt to place the Strathdon settlement sequence in a broader context by examining the presence/absence and form of enclosure on Scotland's lowland east coast (the Scottish Border to the Moray Firth; Fig. 1). In broad terms, Scotland's hillforts form part of a distinctive northern British cluster, both physically and morphologically distinct from those of southern Britain (Harding Reference Harding1976, 361–2; Frodsham et al. Reference Frodsham, Hedley and Young2007, 258). In turn, the east coast Scottish evidence is broken into two broad zones: there are large numbers of hillforts in south-east Scotland (the Scottish Borders and East Lothian) and considerably fewer north of the Forth (Armit & Ralston Reference Armit and Ralston2003, 181; Halliday & Ralston Reference Halliday and Ralston2009, 461). In general, the majority remain undated but considered to be Iron Age in origin (Armit & Ralston Reference Armit and Ralston2003, 172–8; Scarf 6.5).

There have been, of course, numerous individual excavations but only two regional hillfort programmes of survey and excavation in Scotland: East Lothian and Angus. A third smaller zone (the Moray Coast) has also been subject to detailed research and has specific relevance to Strathdon. However, in all three areas no attempt has been made to link the unenclosed and enclosed settlement sequences. The key sites are listed in Table 4.

Table 4 bibliographic references for regional comparanda

East Lothian

East Lothian is the most densely studied region in mainland Scotland (Lelong & MacGregor, Reference Lelong and MacGregor2007, 239–69). Yet among the 350+ varied forms of hillforts and enclosures in the East Lothian HER only 16 (4.5%) have been excavated and dated (Fig. 6; see summary in Cook & Connolly Reference Cook and Connolly2010). Additional excavation within this corpus tends to reveal increased complexity (Haselgrove Reference Haselgrove2009, 226–31). That said there are some broad trends:

Fig. 6 Distribution of sites mentioned in text in East Lothian, Angus, and the Moray Coast (Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2012)

• During the Late Bronze Age, substantial enclosed sites (Traprain Law) are surrounded by a network of smaller curvilinear enclosures (eg, Standing Stone).

• Multivallate enclosures are constructed 600–400 cal bc (eg, Broxmouth and White Castle). with a wide variety of forms and scale of settlement.

• In the closing centuries bc curvilinear enclosures reappear (eg, Fishers Road East and West, St Germains).

• Rectilinear enclosures of various forms are built around the same time (eg, Foster Law); these appear to be filling in gaps in an existing settled landscape.

• While some enclosures are abandoned in the early decades of the 1st century ad, others are maintained.

• New fortifications are established and existing ones refortified in the 4th–5th centuries ad (eg, Traprain Law and Dunbar Castle Park)

• There are no de novo fortifications in the 6th–8th centuries.

Angus and South Aberdeenshire

Angus was as ‘unsorted’ by Haselgrove et al. (Reference Haselgrove, Armit, Champion, Gwilt, Hill, Hunter and Woodward2001, 25). Edinburgh University's Angus and South Aberdeenshire Field School (Finlayson et al. Reference Finlayson, Coles, Dunwell and Ralston1999) identified six types of enclosure and placed them in a regional context (Dunwell & Ralston Reference Dunwell and Ralston2008, 61–89; Fig. 6):

• Large hill-top enclosures dating to before c. 400 cal bc (eg, White and Brown Caterthuns).

• Multivallate enclosures of varying size (100–400 m diameter) with multiple entrances dating to around c. 500 bc (eg, White and Brown Caterthuns and Mains of Edzell).

• Oblong gateless forts with massive walls, frequently vitrified (eg, Finavon, White Caterthun inner) and destroyed by fire 200–1 cal bc (this author argues that they lie at earlier end of this range).

• Small enclosed promontory forts perhaps dating from the middle of the 1st millennium to the closing centuries bc and early centuries ad (eg West Mains of Ethie and Elliot).

• Brochs, with examples built inside earlier promontory forts, dating to the earlier centuries ad (eg, Hurly Hawkin).

• Undated small stone built circular enclosures, c. 20–25 m in diameter, constructed later than the oblong series (eg, Turin Hill).

A number of factors are worth drawing out. First is the variety of multivallate hillforts: it is not clear if the White and Brown Catherthuns (Dunwell & Strachan Reference Dunwell and Strachan2007) are contemporary with smaller enclosures like Mains of Edzell, given the larger error range on dates from the latter (Strachan et al. Reference Strachan, Hamilton and Dunwell2003, 52). Perhaps the most significant factor is the distribution of the oblong forts which shows two tight clusters, with a southern one in Angus, Perthshire, and northern Fife. The precise meaning of the clusters depends upon the function of the oblong series, which is much debated. However, the distribution is very clearly a significant indication of population and/or power structures in the closing centuries bc. The same evidence indicates a clear move from hillforts with multiple entrances to those with none, eg, White Caterthun outer enclosures to the inner oblong fort (Dunwell & Strachan Reference Dunwell and Strachan2007). At present, while there are Late Iron Age defended sites, for example Ironshill East, West Mains of Ethie, or Hurly Hawkin, these appear to represent impressive single households rather than larger enclosed sites (McGill Reference McGill2003; Wilson Reference Wilson1980; Taylor Reference Taylor1982). The presence of Roman goods may reflect their status. Finally, while there are references to early medieval defended sites, for example Dunottar and Dundurn (Alcock Reference Alcock1981), only Dundurn has been confirmed by excavation (Alcock et al. Reference Alcock, Alcock and Driscoll1989). The Edinburgh University Field School failed to find evidence of any new early medieval hillforts (Dunwell & Ralston Reference Dunwell and Ralston2008, 88–9).

Moray Firth coast

The south coast of the Moray Firth was subject to a series of excavations in the 1960s and early 1980s, none of which has been fully published though the evidence has been presented in a series of summary papers (eg, Megaw & Simpson Reference Megaw and Simpson1978, 499). However, the cluster of both hillforts and excavations represents an important although small scale dataset, within another lacuna identified by Haselgrove et al. (Reference Haselgrove, Armit, Champion, Gwilt, Hill, Hunter and Woodward2001, 25). The excavated sequence and key features can be summarised as follows (Fig. 6):

• The timber laced gateway at Cullykhan appears to be contemporary with the oblong fort at Craig Phadrig.

• The oblong series appears to be located at the western end of the Moray Firth while Cullykhan is to the east (Fig. 6).

• There is evidence for internal use in the 3rd–5th centuries ad (eg, Cullykhan and Craig Phadrig).

• De novo fortification occurs in the 4th–9th centuries (eg, Green Castle).

• Burghead featres both elaborate carved bulls and iron nails within its timber-laced rampart.

While the evidence is limited, it is clear that destruction by fire is commonplace in this region's sequence. There is clearly some variation of design and form in the third quarter of the 1st millennium bc as well as an absence of de novo fortification between c. 200 bc and c. ad 300. The relationship between Green Castle and Burghead is unclear and could be well be hierarchical. Finally, it is worth stressing that the early medieval kingdom of Fortriu is now considered to be located north of the Mounth and potentially around Moray (Woolf Reference Woolf2006).

Comparison

Despite the large physical area and limited data set, there are a number of patterns discernible across Scotland's Lowland east coast hillfort sequence. This evidence sits within a broader theoretical context as to the nature and function of enclosure and its putative connection with warfare (eg, Armit Reference Armit2007; Lock Reference Lock2011). To date this debate has focused on the prehistoric period to the exclusion of the early medieval where, in general, a one-to-one relationship between warfare and hillfort construction is assumed (Reference CookCook forthcoming). Given the limited evidence this paper cannot engage in this debate but will touch briefly upon function.

It is argued that in the Late Bronze Age there are large enclosures in East Lothian (Traprain Law; Armit et al. Reference Armit, Dunwell and Hunter2002) and Strathdon (Tap o'Noth outer and Hill of Newleslie). This grouping may also include Angus (Brown Catherthun; Dunwell & Strachan Reference Dunwell and Strachan2007) which has a large hilltop enclosure dating to before c. 400 bc, and should also include Eildon Hill North (Rideout et al. Reference Rideout, Owe and Halpin1992). However, in East Lothian, Traprain Law is surrounded by smaller contemporaneous enclosures (Haselgrove et al. Reference Haselgrove, Fitts and Carne2009). The equivalents have not yet been identified in either Angus or Strathdon.

While the interior of Hill of Newleslie is featureless, Tap o'Noth outer contains over 100 hut platforms and quarry scoops (RCAHMS 2007, 104). It is difficult to imagine how the surrounding area could have supported such a population and so this total may derive from aggregation over time (Bradley Reference Bradley2007, 256). These enclosures compare favourably with Cunliffe's Hill-Top Enclosures (2005, 30–1) which date to the Late Bronze Age, are lightly defended, and appear to be the focus for communal gatherings.

Around 500 bc there is again a series of similar sites across Scotland's east coast: large circular multivallate hillforts with multiple entrances, for example, White Castle (Cook & Connolly Reference Cook and Connolly2010) and Broxmouth (Hill Reference Hill1982) in East Lothian, Brown and White Catherthuns (Dunwell & Strachan Reference Dunwell and Strachan2007) in Angus, and Barmekin of Echt and Hill of Barra in Strathdon. Again, in both Angus and East Lothian there is some evidence for other forms of contemporaneous enclosure. At both Hill of Barra (Cook Reference Cook2012) and Whitecastle (Cook & Connolly Reference Cook and Connolly2010) the defences are more substantial at the entrances, becoming slight banks (Hill of Barra) or terraces (Whitecastle) away from them.

These sites appear to have functioned as meeting points, the variety of entrances perhaps indicating access by different tribes or at different seasons (Dunwell & Strachan Reference Dunwell and Strachan2007). Under such a model it may be possible to argue for different communities constructing specific sections of the enclosing works. That both Hill of Barra and Barmekin of Echt move to single entranced enclosures suggests a radical change in how such sites were accessed which, in turn, may point to significant changes in wider society – perhaps the increasing dominance of one social group over former peers?

This potential linkage begins to break down after 500 bc with an increase in the number and variability of enclosure forms in both East Lothian (Haselgrove Reference Haselgrove2009, 229) and Strathdon. The appearance of promontory forts in Angus and the Moray Coast may also relate to this period, although the evidence is limited (Ralston Reference Ralston2007, 11).

The subsequent increase in number and variability of enclosure forms appears to imply the replacement of broad national trends with more local influences. In Strathdon these changes includes the move from multiple entrances to single ones (Cook Reference Cook2010a; 2012), as discussed. At roughly the same time the unenclosed settlement sequence in Strathdon appears to have become more complex, perhaps involving smaller enclosed elite settlement.

This period also witnesses a clear cultural break either side of the Forth: to the south the number of enclosures continued to grow, with rectilinear enclosures filling in gaps in a densely settled landscape. The construction or maintenance of enclosures continued until the 5th century ad, though with changing numbers and foci (Haselgrove Reference Haselgrove2009, 230).

To the north, the oblong forts appear in three clusters: Moray, Angus, and two sites in Strathdon (Fig. 3). In Angus and Strathdon the oblong series appears to be the final phase of large enclosure (Dunwell & Strachan Reference Dunwell and Strachan2007, 88; Dunwell & Ralston Reference Dunwell and Ralston2008, 72–86; Cook Reference Cook2010b); the stratigraphic relationship of the examples from Moray is presently unknown.

While it would be tempting to argue that the oblong forts relate to conflict, their broad geographical and chronological spread appears more likely to reflect a period of social competition expressing itself through their construction and subsequent destruction. The extended period of their destruction may represent the time required to assemble and transport the necessary resources required to both construct and subsequently destroy them in an appropriate manner. Similar arguments were proposed for funerals and the associated resources required for feasting (Miles Reference Miles1965). In this context, it is worth stressing the difficulty of achieving significant vitrification (Ralston Reference Ralston1986) and it may be that vitrification was the desired outcome for oblong forts and its scale and extent a source of pride and celebration.

Further variation emerges: in Angus small promontory forts and brochs were constructed across the closing centuries bc–early centuries ad (Ralston Reference Ralston2007, 11; Dunwell & Ralston Reference Dunwell and Ralston2008, 86–8). These sites are smaller than earlier enclosures and may reflect the growth of discrete localised elites. However, in Strathdon and the Moray Firth coast, there are no brochs or de novo hillforts and only limited evidence for reuse of promontory forts (eg, Cullykhan, Moray; Greig Reference Greig1972) during this period. Across the whole of the area between the Firth of Forth and the Moray Firth at this time there emerges a distinctive metalwork style and approach to hoarding (Hunter Reference Hunter1997; 2006). Hunter argued that this hoarding pattern indicates a more equal and less hierarchical society, the so-called ‘farmer republics’. To reiterate, this evidence occurs across both Angus and Strathdon and is independent of the presence or absence of brochs and promontory forts. It is not clear if the small enclosed sites of Angus reflect the breakdown of the ‘farmer republics’ or just regional variation.

In the early medieval period the enclosed settlement record is dominated by small numbers of large sites such as Burghead, Green Castle, and Dunottar (Alcock Reference Alcock1988), which demonstrate a considerable variety of forms (Ralston Reference Ralston2004). It is, at present, only in Strathdon where a variety of small scale enclosed sites have been identified (Maiden Castle, Cairnmore, and Barflat). These sites appear to indicate hierarchical settlement, as would be expected from the current models (Driscoll Reference Driscoll1991; Foster Reference Foster1998). The nature of the apparent clustering of enclosed sites and Class I symbol stones at Inverurie and Rhynie and, in turn, their relationship with Burghead and Green Castle is unclear, but may reflect discrete but contemporaneous polities – or perhaps they represent functional or chronological differences. Certainly, Burghead continued to be used and fortified after the 7th century ad, when no more de novo hillforts were built in Strathdon (although Mither Tap was reoccupied) and it may be that the settlement became more hierarchical in the 7th–9th centuries with the series of smaller enclosed sites reflecting the last vestiges of Hunter's ‘farmer republic’ sociey as it became a kingdom (Fraser Reference Fraser2009, 66).

Another complicating factor is Christianity which, following its introduction to Aberdeenshire after ad 500–600 (Alcock Reference Alcock2003, 59–69) is likely to have altered existing power structures and thus hillfort occupation. It is certainly the case that the distribution of Class I and Class II stones are different (RCAHMS 2007, 118–24). Given this, the later reuse of Mither Tap, Bennachie is interesting, Johnston (Reference Johnson1903, 38) and Watson (Reference Watson1926, 264) consider that the name ‘Bennachie’ may mean the ‘hill of blessing’ as opposed to the ‘hill of the Ce’ (Dobbs Reference Dobbs1949) and that it may be linked to early Christian activity. In addition, Mither Tap is at the centre of a cluster of Class II symbol stones (Fraser & Halliday Reference Fraser and Halliday2011, 322) as well as two potentially early medieval Christian centres: Fetternear and Abersnethock (Fraser Reference Fraser2009, 110). However, this can only be a tentative suggestion.

At present it is not clear if this pattern is real or simply reflects the absence of excavation in other areas; certainly the latter makes more sense (Cottam & Small Reference Cottam and Small1974; Dunwell & Ralston Reference Dunwell and Ralston2008, 88). However, it may be that the various boundaries of Scotland's east coast have influenced hillfort design. For example, the cultural boundary north and south of the Forth may have influenced hillfort construction in East Lothian where, unlike the Moray Firth coast, there are no confirmed de novo hillforts in the 6th–9th centuries. A similar pattern is also apparent in Strathdon where no new hillforts are constructed after the 7th century. In addition, there are clear regional patterns north and south of the Mounth in the distribution of specific Pictish symbols (Clarke et al. Reference Clarke, Blackwell and Goldberg2012, 161).

The broad conclusion is that, in the first half of the 1st millennium bc there was some level of linkage in hillfort design from East Lothian (and potentially the Borders) to Aberdeenshire but that after c. 500 bc, and a period of variation and presumably social competition, the record became more diverse and the east coast split into an increasing number of regions and sub-regions. These regional differences are reflected in the presence/absence of hillforts and also in the style and nature of enclosure, for example oblong forts occur north of the Forth and brochs south of the Mounth.

In the early medieval period there appears to be considerable level of regional variation but the data does not yet allow us to define or distinguish between chronological, functional, and geographical variation. Where the evidence does exist it indicates a contraction from multiple small sites to fewer larger or more impressive ones.

Summary and Conclusion

In conclusion, the later prehistoric and early medieval settlement record of Strathdon and the wider north-east of Scotland is exceptionally rich. However, this wealth of material has not been synthesised at a national level. The existing record has been greatly built upon by both recent rescue mitigation and small scale key-hole research. These works have allowed, for the first time the creation of an outline settlement narrative for the area.

During the first half of the 1st millennium bc Strathdon hillforts appear to reflect wider UK trends: there are relatively few and they appear to be aimed at communal gatherings. After c. 500 bc a variety of local factors influence hillfort design and there is an increase in their number and variability, before the emergence of a single dominant single form from northern Fife to Inverness (the oblong series) and then an abandonment of enclosure until the early medieval period. It has not been possible to determine changes in function across the prehistoric period but even if these sites continued to serve or represent a community there is a clear societal change represented by the change in entrances – from multiple to single to none – which, in turn, coincides with a restriction in internal space. The current evidence indicates that hillforts were abandoned before the Roman incursions, perhaps by several hundred years and while they may have been reoccupied there is as yet no evidence for refortification.

In the early medieval period hillforts appear to reflect the emergence of an increasingly hierarchical settlement pattern (the bulk of the population apparently living in open settlements); quite how this relates to either the departure of the Roman state or the emergence of Christianity is unclear.

Within the broader north-east region the contraction of hillforts over time appears to reflect a move from a less hierarchical society, with multiple smaller foci, to a kingdom with centralised resources and significantly fewer hillforts, which tended to be larger or more impressive and may encapsulate this move from ‘farmer republics’ to kingdoms.

This is clearly not the last word on this subject. Hillforts are a varied and complex set of monuments that represent a variety of responses to internal and external pressures and influences. However, we need more data in order to compare and contrast different regions across the totality of the UK's past, and this must begin with more dates and sequences. The way to resolve many of these issues is through large-scale research programmes and well-structured mitigation exercises. However, in both the current economic climate and in the spirit of localism, low impact, tightly defined programmes of key-hole excavation, using volunteers, should be part of the overall package. Such work can achieve significant results for a fraction of the price of larger scale studies.

Acknowledgements

The various constituent projects were funded by The Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, the MacKichan Trust, the Glasgow Archaeological Society, the Hunter Archaeological Trust, the Council for British Archaeology, Aberdeenshire Council, the Greenspan Agency, AOC Archaeology, Oxford Archaeology North, Historic Scotland, and the author. Thanks are also due to the many volunteers and colleagues who gave their free time, advice and support, and in particular the late Ian Shepherd, Moira Greig, Bruce Mann, Dr Ann MacSween, Dr Fraser Hunter, Dr Anne Crone, Dr Ciara Clarke, Dr Denise Druce, Dr Gordon Cook, Strat Halliday, Rachel Newman, Hana Kdolska, Stefan Sagrott, Rob Engl, Lindsay Dunbar, Martin Cook, Jamie Humble, Gary Stratton, Stuart Dinning, Anna Hodgkinson, Graeme Carruthers, and David Connolly, for the illustrations. Martin Cook, Bruce Mann, David Connolly, Fraser Hunter, Derek Hall, and three anonymous referees commented on drafts of the text. All mistakes remain the responsibility of the author.