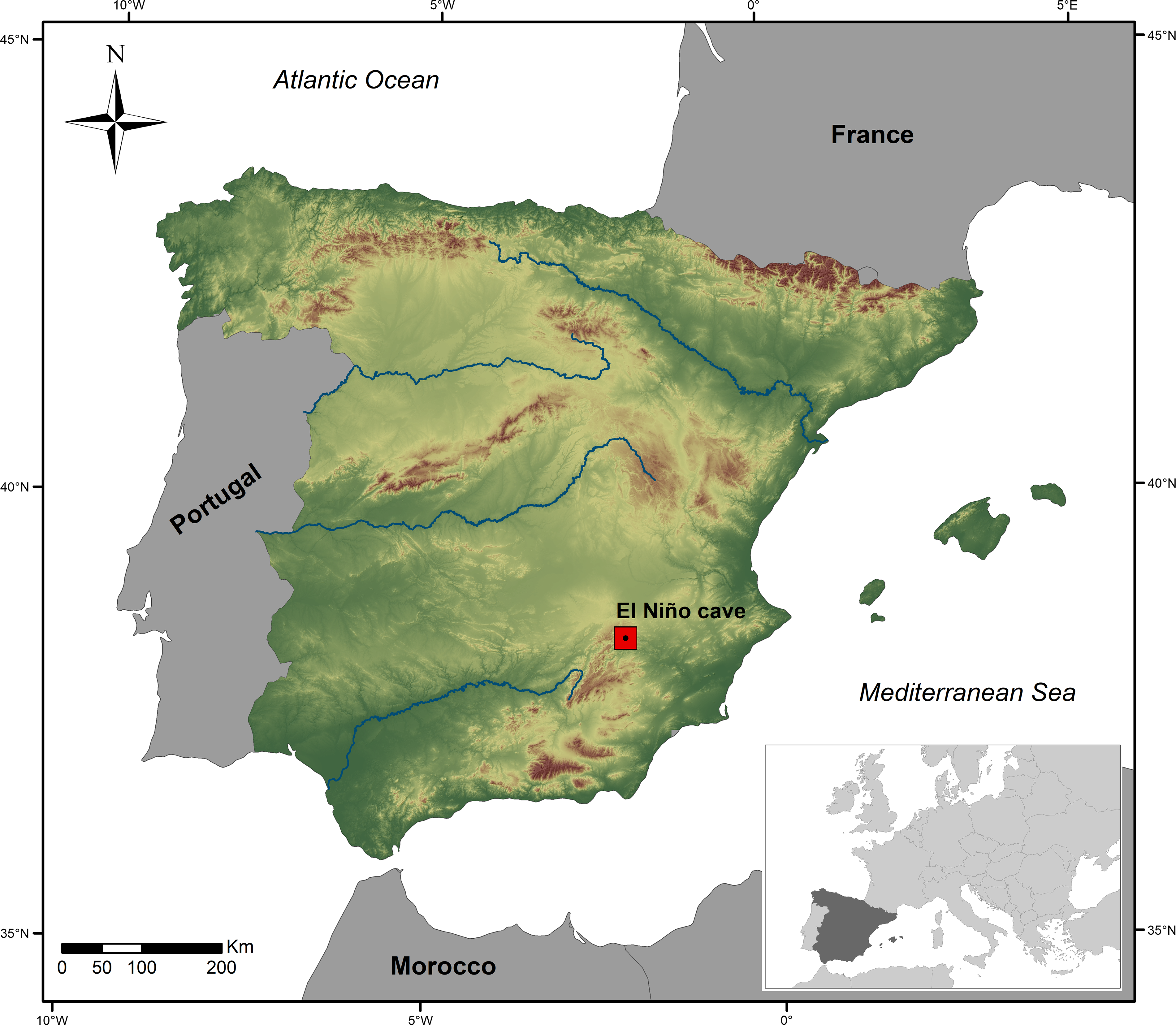

In contrast to other Spanish regions, inland Iberia, mostly defined by the Central Meseta (plateau), is characterised by a reduced number of Palaeolithic sites, especially from the Upper Palaeolithic (Straus Reference Straus2018), despite recent discoveries (Yravedra et al. Reference Yravedra, Julien, Alcaraz Castaño, Estaca-Gómez, Alcolea González, de Balbín-Behrmann, Lécuyer, Marcel and Burke2016; Cascalheira et al. Reference Cascalheira, Alcaraz Castaño, Alcolea, Andrés, Arrizabalaga, Aura-Tortosa, Garcia-Ibaibarriaga and Iriarte-Chiapusso2020). Many of these sites correspond to open-air finds. In this framework, El Niño cave (Aýna, Albacete), located in the Sierra de Alcaraz mountain range on the south-eastern border of the Central Meseta (Fig. 1), constitutes a key site, hosting one of the few Palaeolithic sequences of the region, along with Palaeolithic and post-Palaeolithic rock art.

Fig. 1. Location of El Niño cave (map: A. García-Moreno)

The site was first published in 1971 (Almagro-Gorbea Reference Almagro Gorbea1971), which concentrated on the Upper Palaeolithic rock art and the Levantine Style Art at the site. In 1973, fieldwork directed by Iain Davidson documented the archaeological deposits (Higgs et al. Reference Higgs, Davidson and Bernaldo de Quirós1976), which evidenced the human use of the cave during the Middle and Upper Palaeolithic, recent prehistory (Neolithic and Chalcolithic), and maybe the Mesolithic. The results of the excavation were included in Davidson’s PhD thesis (1981) but were not published, and the site remained almost unknown. For this reason, since 2008 we have been conducting a comprehensive review of the site through the study of the Palaeolithic paintings, the analysis of the archaeological materials, and a dating programme (García-Moreno et al. Reference García-Moreno, Cubas, Davidson, Garate, López-Dóriga, Marín-Arroyo, Ortiz, Polo-Díaz, Rios-Garaizar, San Emeterio, Torres, Gamo and Sanz2016).

The aim of this paper is to present El Niño cave to a broader, international audience, due to its potential for studying Middle Palaeolithic, Upper Palaeolithic, and Neolithic human settlement in inland Iberia.

ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITE

The site is located at 812 m above sea level in the Barranco del Infierno ravine, part of the Mundo River canyon, a tributary of the Segura River (Fig. 2). At the cave opening is a small rock shelter where Levantine style paintings are located. The cave is about 60 m long and oval in shape, with a speleothem formation dividing it into two chambers, the outer of which hosts the main panel of Palaeolithic paintings.

Fig. 2. Aerial view of the cave’s entrance and its landscape (photo: Cineproad S.L.)

Fieldwork in 1973 (Davidson Reference Davidson1981; Davidson & García-Moreno Reference Davidson and García-Moreno2013) focused on two trenches outside the cave entrance (Trenches 1 & 2). A discontinuous sequence of 11 archaeological levels was defined. Levels XI (base) to III–IV correspond to the Middle Palaeolithic. Levels II and I appear to contain mixed assemblages, with both Middle Palaeolithic and post-Palaeolithic materials, and a wide range of dates, arguing against the archaeological integrity of these upper levels (García-Moreno et al. Reference García-Moreno, Rios-Garaizar, Marín-Arroyo, Ortiz, Torres and López-Dóriga2014).

A further two test pits were dug: one at the foot of the Levantine paintings (TAL, for Trinchera Arte Levantino), where a Neolithic sequence was identified (García-Moreno et al. Reference García-Moreno, Cubas, Marín-Arroyo, Rios-Garaizar, Ortiz, Torres, López-Dóriga, Polo-Díaz, San Emeterio and Garate2015), and another below the main panel of Palaeolithic paintings, which yielded a small collection of undiagnostic lithics and several faunal remains.

MIDDLE PALAEOLITHIC

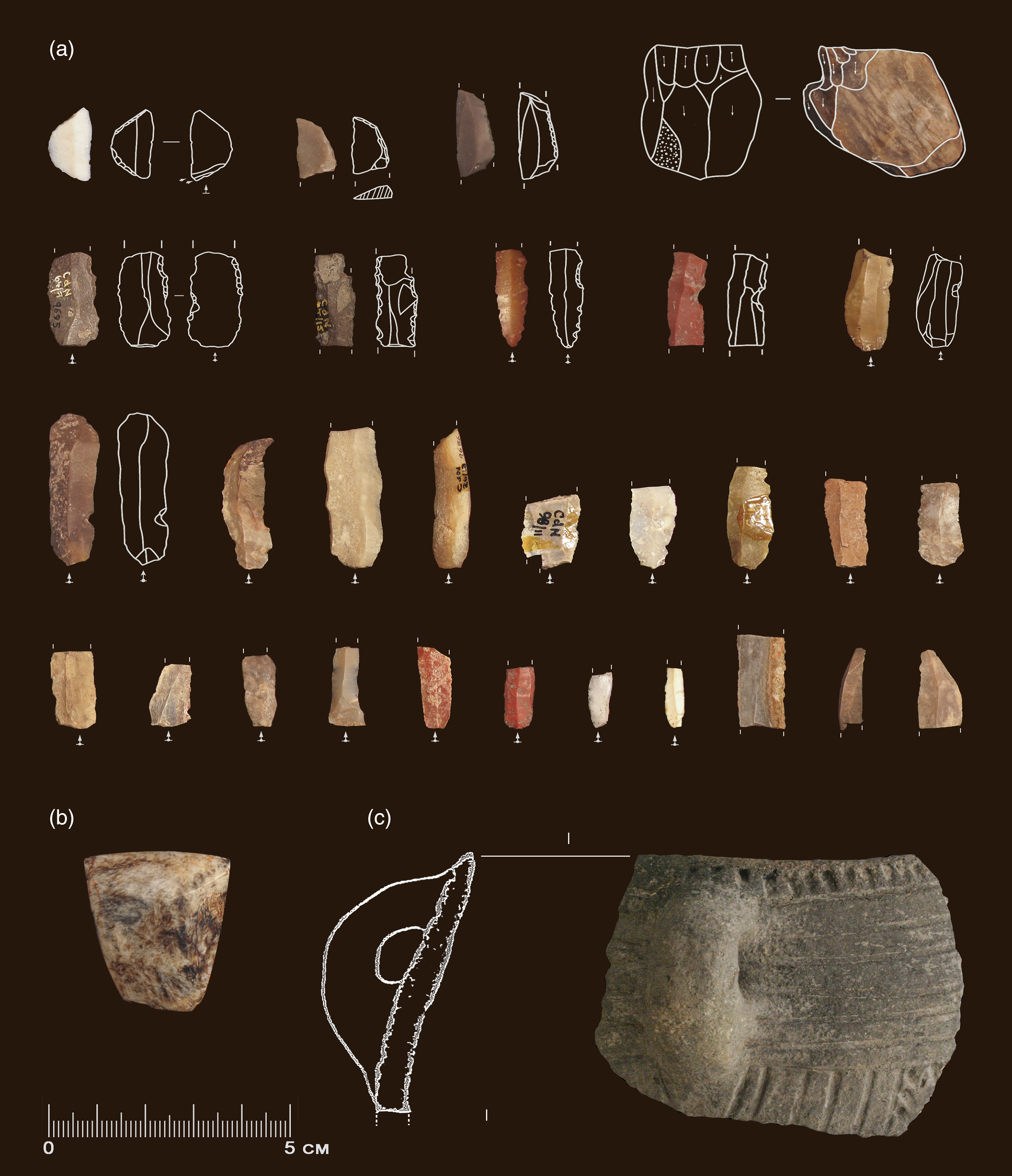

Most archaeological remains from Trenches 1 and 2 came from Levels XI and the unit formed by III–IV, corresponding to two Middle Palaeolithic occupation phases.

Level XI was dated by Amino Acid Racemization (AAR) on an Equus molar at 55.55 ka (LEB-9570). The lithic assemblage is characterised by a variety of reduction sequences on flint (Levallois & Quina) and quartzite (Discoid & Quina), resulting in large, retouched flakes transported to the site and resharpened in situ. Lithic tools comprise two retouched flakes and three side-scrapers (Fig. 3a). The fauna is dominated by horse (Equus sp.), followed by ibex (Capra sp.) and red deer (Cervus elaphus). Whereas ibex is still common in the precipitous immediate landscape, the presence of horse and other large ungulates, such as aurochs or rhino, also evidences the exploitation of open plains. Level XI also provided 17 plant remains, corresponding to mineralised endocarps of Celtis tp. australis fruits, which may have been consumed by Neanderthals (Fig. 4). Together, evidence suggests Neanderthal occupations during this phase involved the exploitation and transport of distant resources and the ramification of in situ lithic production through Quina technology.

Fig. 3. Middle Palaeolithic industry: (a) Level XI; (b) refits from Level III–IV; (c) Level III–IV (photo: J. Rios-Garaizar, A. García-Moreno & A. San Emeterio)

Fig. 4. Endocarp of Celtis tp. australis (photo: I. López-Dóriga & A. García-Moreno)

Due to the lack of collagen, bone apatite from Level III–IV was radiocarbon dated to 33,380–32,250 cal bp Footnote 1 (UGAMS-7739: 28,660±90 bp) and 32,910–31,920 cal bp (UGAMS-7737: 28,270±80 bp), which is too young for Middle Palaeolithic (Higham et al. Reference Higham2014). Despite the apparent consistency, these dates provide minimum age estimates as young carbonate cannot be fully removed from bone apatite and ages are nearly always erroneously young (Wood et al. Reference Wood, Barroso Ruiz, Caparrós, Jordá Pardo, Galván Santos and Higham2013). In contrast with Level XI, local quartzite is largely dominant over flint. Three series of refits (Fig. 3b) demonstrate quartzite cobbles were knapped in situ following a Quina production schema. There is also evidence of cordal Discoid and Levallois knapping on quartzite, producing typical Levallois flakes and Pseudolevallois points. Flint was introduced as final tools, such as a Mousterian point, two side-scrapers, and Levallois flakes (Fig. 3c). Fauna was limited to a few poorly preserved remains corresponding almost exclusively to Capra sp. In this case, evidence points towards a shift in subsistence strategies compared to earlier occupations, based on the immediate exploitation of local resources, including in situ knapping of local quartzite and transport of flint tools.

UPPER PALAEOLITHIC PAINTINGS

Cave art attests the use of the site during the Upper Palaeolithic. The main panel, located in the half-light of the outer chamber, includes nine figures comprising typical Palaeolithic representations: two male and three female deer, two ibex, one bovid, and one horse (see Garate & García-Moreno Reference Garate and García-Moreno2011 and the discussion of scenes in Palaeolithic art in Davidson Reference Davidson, Davidson and Nowell2021 for a detailed description of the composition of the panel) (Fig. 5). The test pit below the panel contained a small layer of ash with a few bones, with the apatite of one radiocarbon dated to 27,280–27,020 cal bp (UGAMS-7738: 22,780±60 bp), which is consistent with a Late Gravettian and/or Solutrean attribution to the paintings or, at least, some of them (Garate & García-Moreno Reference Garate and García-Moreno2011).

Fig. 5. Main panel of Palaeolithic paintings (photo: D. Garate; illustration: D. Garate)

A second panel, found in a small side gallery of the inner chamber, includes two small partial figures of a horse, an ibex, and a snake made of parallel, sinuous lines with interior rings in its upper half (Garate & García-Moreno Reference Garate and García-Moreno2011). The characteristics and motifs stylistically relate El Niño’s rock art to both the Cantabrian and Mediterranean regions and imply the connection between these areas during the Upper Palaeolithic.

NEOLITHIC

Evidence of post-Pleistocene occupations was found in the upper levels of Trenches 1 and 2 mixed with older materials and mainly in a test pit below the Levantine paintings, where a sequence of five archaeological levels was identified (García-Moreno et al. Reference García-Moreno, Cubas, Marín-Arroyo, Rios-Garaizar, Ortiz, Torres, López-Dóriga, Polo-Díaz, San Emeterio and Garate2015). Bone collagen from Level IIb was radiocarbon dated to 5060–4840 cal bp (GdA-2102: 6065±40 bp). Lithic industry is consistent with a Mesolithic and/or Neolithic age, made mostly of flint, and characterised by microblade technology, including four geometric microliths (Fig. 6a). A polished adze was found out of stratigraphic context (Fig. 6b).

Fig. 6. Neolithic knapped (a) and polished (b) lithic industry and pottery (c) (photo: A. García-Moreno, A. San Emeterio, J. Rios-Garaizar & M. Cubas)

Pottery technology can be attributed to the Early Neolithic (Martí-Oliver Reference Martí Oliver1988). All fragments were handmade, most of them fired in a mixed firing (Cubas et al. Reference Cubas, Sánchez-Carro, Lozano-López and García-Moreno2020). Decorations are scarce, usually consisting of plastic applications, such as lugs and cordons, or incisions (Fig. 6c; Cubas et al. Reference Cubas, García Moreno, Mingo, Barba, Canales, Gamo Parras and Sanz Gamo2016). The vessel morphologies identified suggest pottery was used for food storage. Several potsherds of Bell Beaker pottery confirm the use of the cave also during the Chalcolithic.

Ungulate remains mostly consist of ovicaprids, either goats or sheep. A significant number of rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) remains were also found, as is usual in Mediterranean Spain. The site also contains post-Palaeolithic paintings, located over the outer wall of the cave entrance. The panel, assigned to the Levantine style, is composed of ten human representations. Taken together, current evidence suggests Neolithic occupations at El Niño related to pastoralism, possibly as part of a transhumance system combining the open lowlands and the mountainous highlands of the Segura River basin (Davidson Reference Davidson1980).

SUMMARY

In conclusion, El Niño cave enables further study of the dynamics of prehistoric human settlement in south-eastern Iberia. Fifty years later, the review of the 1973 excavation and the study of its archaeological materials and rock art provide new insights on the evolution of Neanderthal populations, the occupation of inland Iberia during the Upper Palaeolithic, and the process of neolithisation in south-eastern Spain.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Cineproad S.L. for providing Figure 2. Research at El Niño cave was funded by the Instituto de Estudios Albacetenses ‘Don Juan Manuel’. We would like to thank the Editor and the reviewers for their suggestions and comments, which helped to improve the quality of this paper. The excavations at Cueva del Niño were possible because of the support of Eric Higgs. Helen Higgs, who ran the logistics for those excavations while looking after Eric and three children, Bryn, Meryn, and Penaran, passed away in June 2021. This paper is dedicated to them, because it would not have happened without them.