Banjo enclosures remain a relatively enigmatic site type within British Iron Age studies. Despite the long history of archaeological research into this period, these sites continue to be under-represented within the corpus of survey and excavation material. There is an imbalance among the level, focus, and quantity of archaeological work that has been undertaken for later prehistoric Britain, and this imbalance is present in our understanding of these sites both individually and within wider landscape and regional contexts. This means that archaeologists have found it difficult to describe these sites, categorise them, and integrate them into wider Iron Age landscape and settlement studies.

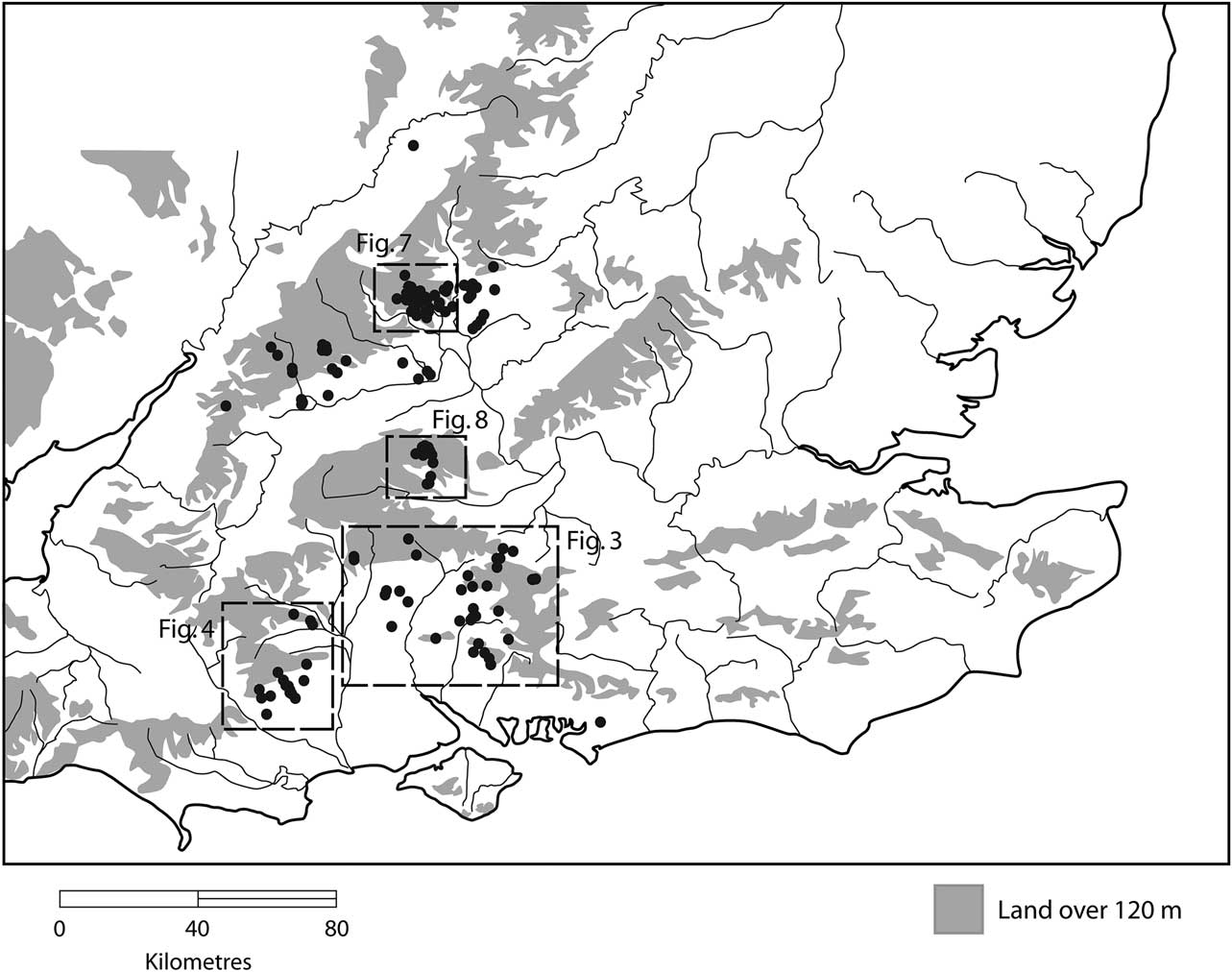

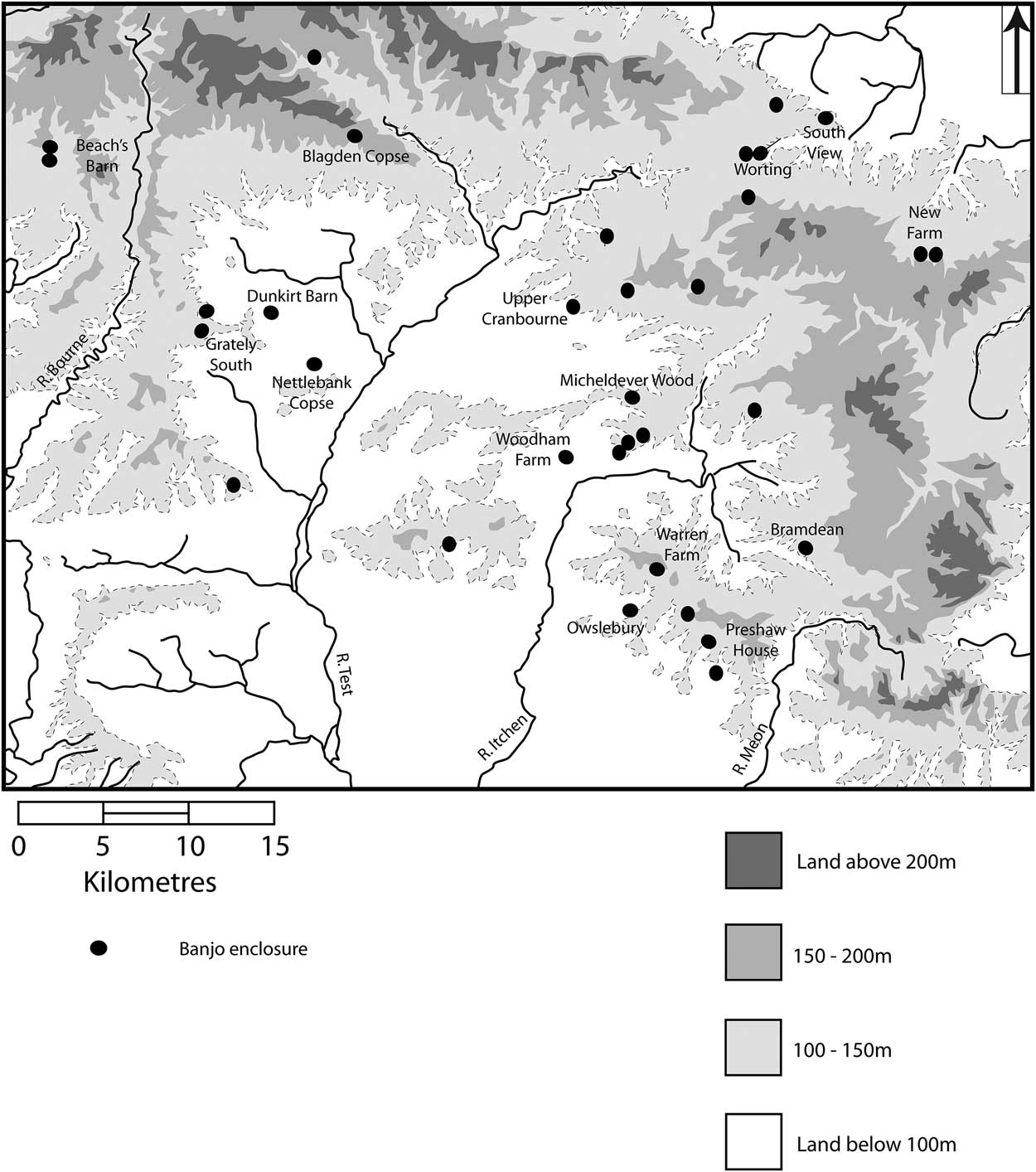

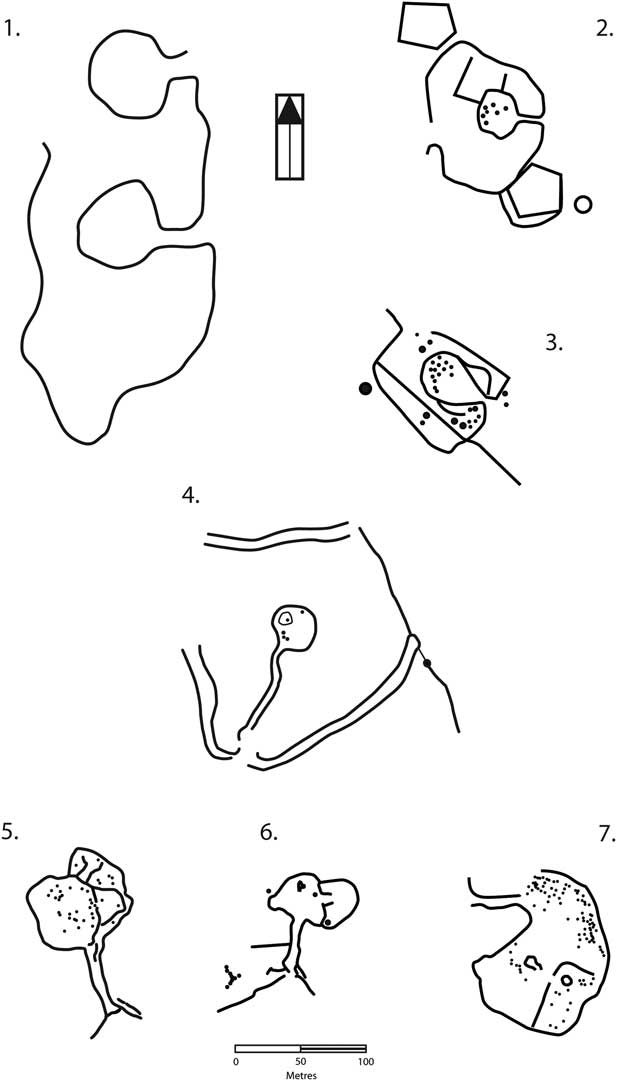

To date more than 140 banjo enclosure sites are known in Britain (Historic England Archives Monuments Information England database [HE AMIE]: Kenney & Lyons Reference Kenney and Lyons2011, 82). The distribution of known sites is at present strongly weighted towards central southern England, which is defined here as the counties of Berkshire, Dorset, Hampshire, and Oxfordshire with parts of Buckinghamshire, Gloucestershire, Wiltshire, and West Sussex also included (Fig. 1). Though the quantity of identified sites has increased, only 16 sites have undergone some form of excavation (Fig. 2 provides some examples), and nine of these are located in Dorset, Hampshire, and Wiltshire. As a result sites in this area have been used as the major sample from which interpretive frameworks have developed. This has posed problems, for these excavations since the 1930s have been an assortment of research, rescue, and commercial development excavations, which has led to a disparity in the techniques used, the length of excavation, and the extent of excavation and sampling. This makes it more difficult to obtain a balanced perspective on our understanding of these sites or to create a coherent framework from which to develop interpretations. Development-led archaeological work resulting from Planning Policy Guidance 16 (PPG16) and Planning Policy Statement 5 (PPS5) has yet to have a significant impact, although it has yielded examples excavated as far afield as Cambridgeshire, Bedfordshire, Warwickshire, and west Wales.

Fig. 1 A distribution map of banjo enclosures in central southern Britain

Fig. 2 Examples of excavated banjo enclosures. 1: Caldecote, Cambridgeshire (after Kenney & Lyons Reference Kenney and Lyons2011, 71, fig. 3); 2: Nettlebank Copse, Hampshire (after Cunliffe Reference Cunliffe2005, 246, fig. 12.6); 3: Micheldever Wood, Hampshire (after Cunliffe Reference Cunliffe2005, 246, fig. 12.6); 4: Bramdean, Hampshire (after Cunliffe Reference Cunliffe2005, 246, fig. 12.6); 5: Carne’s Seat, West Sussex (after Holgate Reference Holgate1986, 38, fig. 5); 6: Tomlin’s Gate, Oxfordshire (after Hingley Reference Hingley1982, 155, fig. 43)

We are fortunate to be in a position where, since the 1990s, there has been a significant increase in sites identified through aerial survey, particularly in the upland areas of the Lambourn Downs and Cotswolds. Added to this, three recent excavations of enclosures in Bagendon, Gloucestershire by Tom Moore; Rollright Heath, Oxfordshire by the author and Duncan Sayer; and North Down, Dorset by Miles Russell and Paul Cheetham have added further details and material to the archaeological dataset.

This paper provides a review of our current understanding of banjo enclosures and suggests new directions for research. It has been written partly as a response to the increase in the quantity of known sites, the diversity of forms identified, and the lack of a wide-ranging review of these sites since the 1990s. Its aims are relatively simple: to review and reassess previous work that has occurred, to outline discussions of form, function, and date, and to re-evaluate the current status of banjo enclosures within Iron Age studies so that we can better understand their relative position in British archaeology. By outlining a relatively simple categorisation methodology we can better define them individually, which will, in turn, help us better understand their context, associations, and possible functions. The incorporation and discussion of recent research outside Wessex adds depth to our developing knowledge of banjo enclosures more widely. By using these to reassess our current interpretations we can redefine both our understanding of them and reinvigorate future research agendas that incorporate them.

DEFINING ‘BANJO’ ENCLOSURES

The term ‘banjo enclosure’ was first coined by Perry in the 1960s (Reference Perry1966; 1969) to describe a unique set of cropmark sites identified in aerial surveys across the Hampshire downs and wider Wessex region. The enclosures were much smaller than most other (presumed) Iron Age cropmark sites and had a number of distinct features, such as elongated entranceways with adjoining antennae ditches, which made them immediately recognisable. At the time, Perry himself admitted ‘banjo’ enclosure was ‘perhaps an unsatisfactory name, but one which in the absence of an all-embracing geometric term, or clear proof of their date or function was considered reasonably appropriate’ (1966, 39). The original definition that Perry (Reference Perry1969, 37) provided for banjo enclosures was thus:

‘Basically they consist of circular, sub-circular and sub-rectangular enclosures ranging in size from under half-an-acre to an upper limit of about one-and-a-half acres [roughly 0.2–0.6 ha]. The enclosure is approached by a funnel-like entrance formed by ditches which run more or less parallel away from the enclosure and then swing outwards in form’.

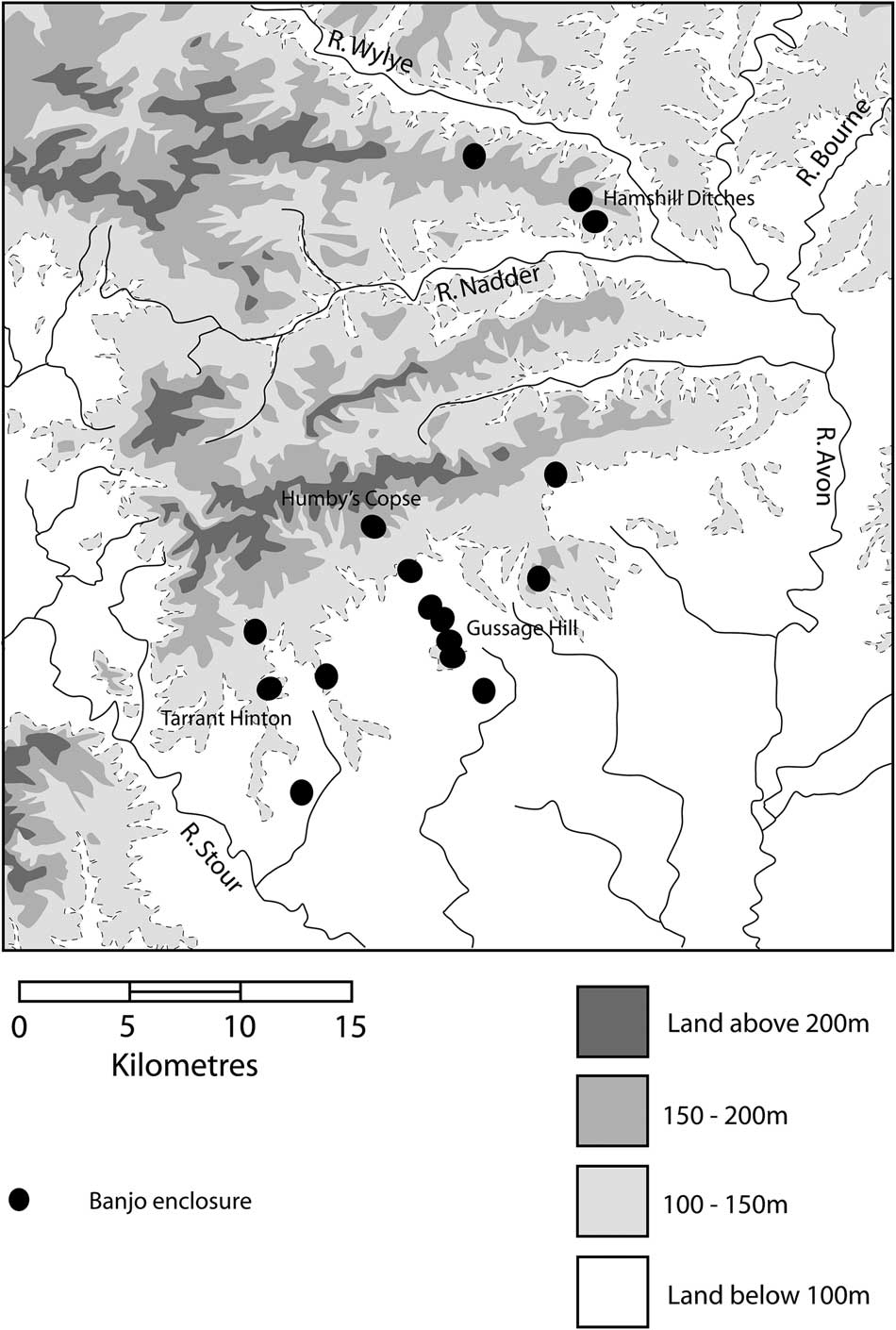

While there are earlier examples of sites being identified that had these characteristics, including Hamshill Ditches (Wiltshire), Gussage Hill (Dorset), and Pewsey Down (Hampshire), they were interpreted as ‘spectacle’ enclosures by Crawford and Keiller (Reference Crawford and Keiller1928). Perry’s work acted as a watershed. His aerial survey was the first regional study of these cropmark sites and, along with his excavations at Bramdean (Hampshire; Fig. 2.4) in the 1960s and 1970s, it focused attention on this form of enclosure. The collation of aerial photographic surveys within southern Britain led to the identification of ‘banjo’ enclosure sites across Hampshire (Fig. 3) and Dorset (Fig. 4). As the effectiveness of this method has developed and coverage has expanded so has our knowledge of these sites. The growth in numbers meant Perry’s term was widely adopted relatively quickly and by the 1980s it had become a defined term for the Monuments Protection Programme (MPP). It is now used by Historic England in its thesaurus of archaeological terms.

Fig. 3 Distribution of banjo enclosures in Wessex

Fig. 4 Distribution of banjo enclosures on Cranborne Chase

The description of the size, shape, and form of this particular type of enclosure has never been significantly altered; only a few minor changes were introduced in the MPP:

‘A banjo enclosure comprises a central area, usually of curvilinear plan and less than 0.6ha in extent, bounded on all sides by a ditch and outer bank, a single entrance approached by double parallel ditches defining a trackway, and some kind of paddocks may be attached to the central enclosure and/or the trackway, and in some cases the whole complex is enclosed within a compound’ (Darvill et al. Reference Darvill, Saunders and Startin1987, 399–400; Hingley & Darvill Reference Hingley and Darvill1988).

A good example of a so-called ‘classic’ site is the Nettlebank Copse (Hampshire) banjo enclosure (Fig. 2.2). Excavated in the 1990s as part of the Danebury environs programme (Cunliffe Reference Cunliffe2000), it was identified as an isolated enclosure with few identifiable features in its immediate environment. This permitted Cunliffe to focus solely on the enclosure itself and it remains the only site to have been fully stripped with all features excavated. The site itself is a sub-circular banjo enclosure, approximately 0.25 ha in size with a narrow entranceway and antennae ditches that run for c. 50 m. A geophysical survey of the site identified a number of internal features indicative of activity or use (Cunliffe & Poole Reference Cunliffe and Poole2000, 9).

Banks and ditches

Beyond the size, shape, and form of these sites, as outlined in the MPP definition above, we can outline further defining features to help us understand and interpret them. Perhaps the most distinct features are the banks and ditches of the enclosures themselves. A key identifiable feature are the antennae ditches that extend away from the enclosure and run parallel to one another for at least part of their length. Whilst we can argue the ditches as features themselves are not extraordinary – most examples are characteristically V-shaped ditches and over a metre deep – it is their length or association with other features that are usually of interest. Antennae ditches can differ dramatically in length from 10 m to 90 m; they can be straight and narrow or short and curved.

Earthwork sites that have survived to the present day, or at least until they were recorded, have all been described as having a bank outside of the ditch rather than inside. External banks have all been identified at Gussage Hill (Fig. 9.1, below), Hamshill Ditches, Micheldever Wood (Hampshire; Fig. 2.3), Blagden Copse, and more broadly in Britain, such as in west Wales at Canaston Wood (Pembrokeshire; Barber & Pannett Reference Barber and Pannett2006). In some instances excavation has confirmed this phenomenon: at Rollright Heath primary deposition in the enclosure ditch indicated that the bank was on the outside (Fig. 9.4, below). The presence of this feature has particularly influenced interpretations of the function of banjo enclosures, with great emphasis placed on the non-defensive nature that an external bank implies. Overall, however, the evidence is inconclusive. Other excavations have not necessarily corroborated this pattern. At Nettlebank Copse excavation identified numerous phases of recutting of the enclosure ditch, which erased much of the evidence of any bank on either side of the ditch, if there ever was one (Cunliffe & Poole Reference Cunliffe and Poole2000, 41). Perry (Reference Perry1982, 66) was far from convinced that an external bank surrounded the entire enclosure at Bramdean, though he references some primary deposition in the enclosure ditch in places, which suggests an external bank (Perry Reference Perry1974, 45). Collis (Reference Collis1968; Reference Collis1970; Reference Collis2006) makes no mention of an external bank at Owslebury (Hampshire). Although it continues to provide an interesting discussion point it is difficult to confirm whether all sites had an external bank.

Landscapes and contexts

The location of banjo enclosures within the landscape is argued as evidence of the functions that sites served. Large numbers of these enclosures are located in what are considered ‘upland’ areas of southern Britain, including the Cotswolds, the Lambourn Downs, the Hampshire Downs, and Cranborne Chase. These landscapes are typically over 100m above sea level, formed of rolling hills and valleys with underlying chalk and limestone geology. The soils are usually shallow but fertile, free draining, and – when well manured – capable of sustaining most agricultural practices. Modern intensive farming regimes have taken place in these areas since the Second World War, and they are well known for having sustained pastoral farming economies in previous centuries. Within upland regions many of the banjo enclosure sites face downhill, often towards water sources, and are located at the cusp of local changes in underlying geology and soils (Collis Reference Collis1970, 254; Hingley Reference Hingley1984a, 81–3); this siting may be as much about impact within the local landscape as it is about exploiting the soil changes.

Fewer banjo enclosures are found along the fertile gravels of major river systems but are probably no less important. Examples have been identified along the Thames in Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire, and its tributaries at Ashton Keynes (Hey Reference Hey2007) and Blackditch Bypass (Benson & Miles Reference Benson and Miles1974; Hingley Reference Hingley1999; Lambrick & Robinson Reference Lambrick and Robinson2009). As yet none of these sites have been excavated, but based on their locations they appear to form part of larger complexes of enclosures, tracks, and possible field systems, which appear throughout the Upper Thames Valley during the later Iron Age.

Banjo enclosures are present in different regional and geological locations, and their proximity to other identifiable features and sites is also extremely varied. They occur in a variety of scenarios: as single sites with no clear association with other features, as a single enclosure in a larger complex, as pairs of enclosures, and on rare occasions as a trio within a much larger complex of enclosure and field systems. Nettlebank Copse is only one example of an isolated site that has no close association to other enclosures or features within the landscape.

Alternatively, single banjo enclosures can belong to complexes within larger ditched systems such as Rollright Heath; here the enclosure is surrounded by a multiple ditch system to create a larger enclosure. They can form part of a larger enclosure complex by facing other features with their antennae ditches connecting internally to other linear features as at Warren Farm (Hampshire; Perry Reference Perry1974, 64), or they can be at the periphery of a site facing away from the main complex with their antennae ditches doubling back behind the enclosure connecting to other features as at Bramdean. Individual enclosures where antennae ditches join linear dyke systems that run at right-angles to the banjo have also been identified at Dunkirt Barn (Oxfordshire) and Blagden Copse.

Double banjo enclosures have usually been identified as being side-by-side in form. These can be in ‘linear’ form such as Beach’s Barn (Dorset) and Gussage Hill. At Gussage Hill, two double banjo complexes with associated linear ditch systems occur in close proximity (c. 1000 m) following the contours of the hill (Barrett et al. Reference Barrett, Bradley and Green1991, 234), with a further two immediately south-east of the complex. At Hamshill Ditches the two enclosures occur side-by-side as annexing enclosures facing a much larger curvilinear enclosure (Bonney & Moore Reference Bonney and Moore1967).

Perry’s aerial surveys identified a number of sites within the Wessex region that existed within larger field systems; the same is true of some of the Cotswold examples (Moore Reference Moore2006, 143). At least one triple banjo enclosure complex has been identified at Weston Patrick (Hampshire); here three adjacent enclosures face a larger curvilinear enclosure (though this may be a later phase) and connect with an elongated linear feature (Perry Reference Perry1974, 66).

Dating & phasing

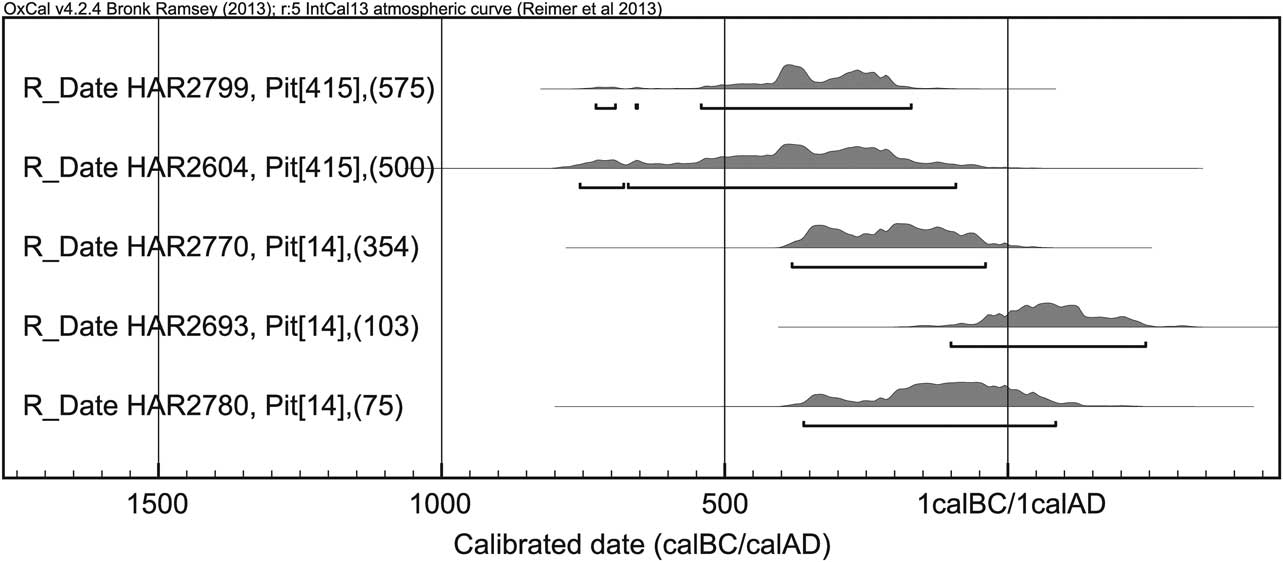

Dating these sites remains difficult. To date, only five radiocarbon dates have been published for banjo enclosures, all from two pits at the Micheldever Wood site (Fasham Reference Fasham1987, 60) (Table 1; Fig. 5). There are a number of reasons for the lack of absolute dates: many sites were excavated prior to the use of wide-scale radiocarbon dating in archaeology; there was an apparent lack of necessity due to the existence of a wider chronological framework; the poor preservation of environmental data; and the imposition of financial constraints. In many instances the dating of these sites is based on local and regional ceramic frameworks, which are broad to say the least. Whilst this is far from satisfying we continue, for the moment at least, to deal with relative chronologies.

Fig. 5 Radiocarbon dates from two pits located within the banjo enclosure at Micheldever Wood, Hampshire

Table 1 Radiocarbon dates from Micheldever Wood, Hampshire

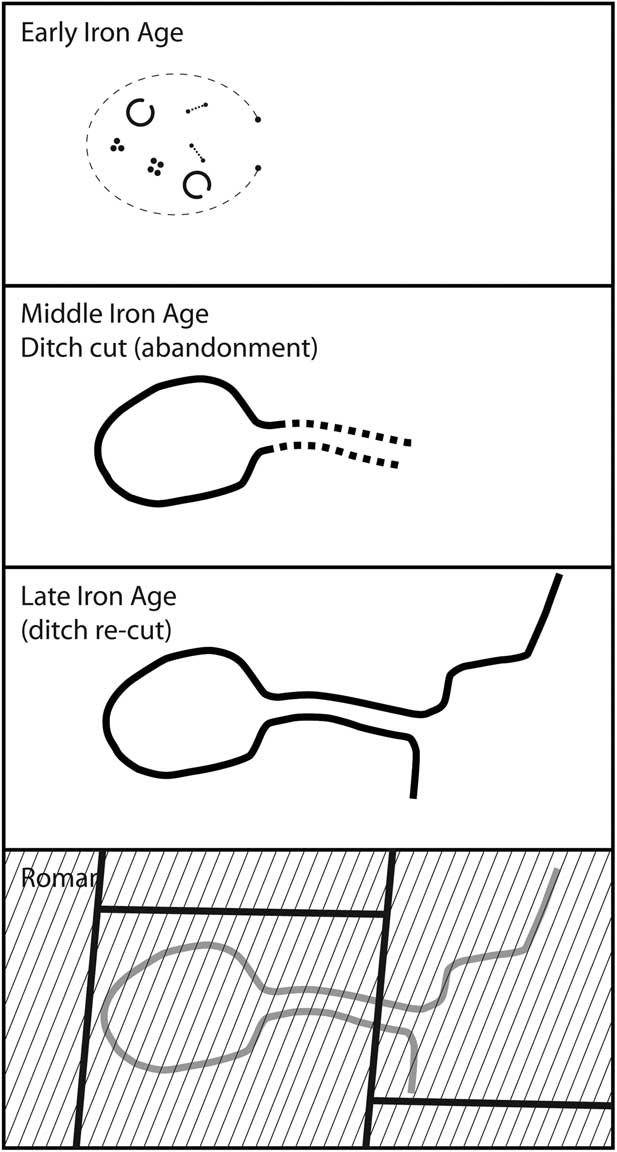

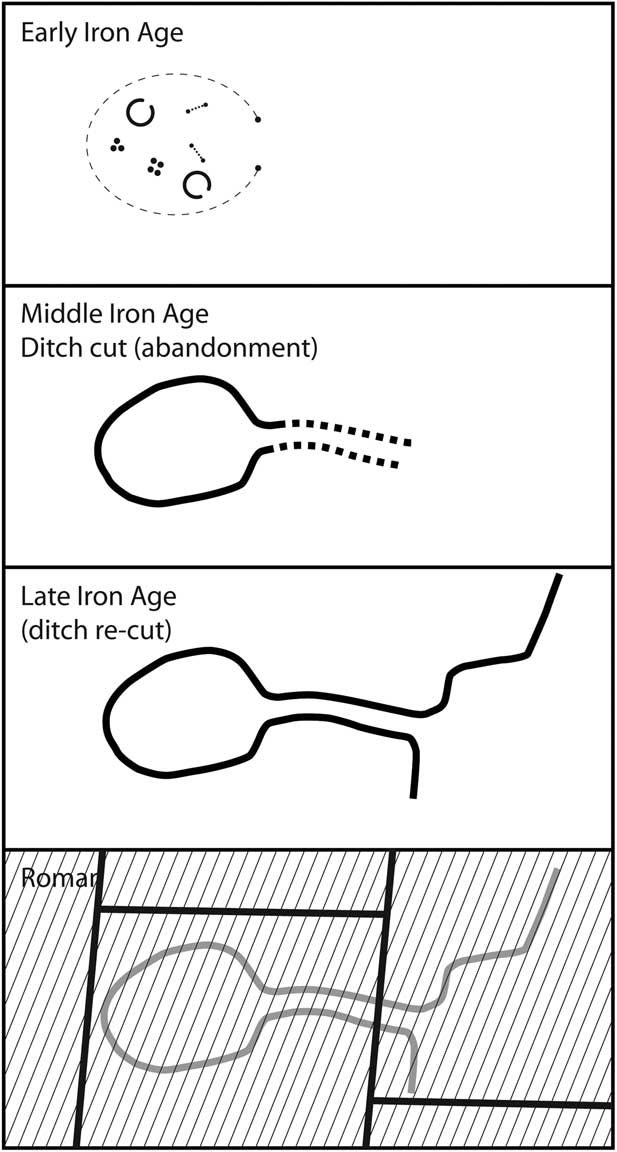

Recovered finds from excavated banjo enclosure sites place them broadly within the Middle to Late Iron Age of southern Britain, c. 400/300 bc to ad 43. There is no indication that these sites existed in the Early Iron Age, although material has been identified from three excavated sites indicating earlier activity. At Nettlebank Copse the Early Iron Age marked the main period of settlement activity (Cunliffe & Poole Reference Cunliffe and Poole2000, 129); at Bramdean, Perry (Reference Perry1982, 68) identified an earlier phase through pit use; and at Micheldever Wood Fasham (Reference Fasham1987, 6) dated an activity phase to the Early–Middle Iron Age transition. In all instances there does not appear to have been a significant break between Early and Middle Iron Age phases of use, suggesting a level of continuity in the evolution of the site to banjo enclosure form.

Many of the banjo enclosures discussed in this paper fit within a broad Middle Iron Age chronology. Most excavations, such as Beach’s Barn and Bramdean, have provided material of this period. However, it is only really at sites like Nettlebank Copse that excavated finds have given some clarity. Cunliffe dated the initial creation of the banjo enclosure ditch to Danebury ceramic period (cp) 6, suggesting a date of 310–270 bc (Cunliffe & Poole Reference Cunliffe and Poole2000, 131). Although Brown (in Cunliffe & Poole Reference Cunliffe and Poole2000, 66) argues that the saucepan styles fit within a much broader Danebury cp 6–7 phase (310–50 bc), both agree that the date is likely in the early 3rd century bc.

The excavations at Nettlebank Copse also revealed some interesting site phasing. The earlier phase enclosure construction was only preserved in small remnants due to significant over-cutting in the later phase of the enclosure ditch. The complete silting up of the first cut led to the interpretation that the site was abandoned for some 200 years soon after the enclosure ditch was excavated (Cunliffe & Poole Reference Cunliffe and Poole2000, 131). This rapid falling out of use is not only observed at Nettlebank Copse. At Owslebury excavations revealed that the banjo enclosure ditch was the earliest phase of a settlement site that was occupied at various times from the Middle Iron Age through to the Late Roman period (Collis Reference Collis2006, 156). The banjo enclosure existed for only a relatively short period of time in the Middle Iron Age before the ditches were filled in completely (recorded as a single homogeneous fill). As at Nettlebank Copse the site was abandoned for some 200 years, though unlike Nettlebank where the banjo enclosure was redug and reused, at Owslebury the site became an agglomeration of sub-rectangular enclosures that was very different to the banjo enclosure that preceded it (Collis Reference Collis1996, 91). This infilling of enclosure ditches is potentially mirrored elsewhere. At Wavendon Gate (Bedfordshire), an enclosure with antennae ditches had a ditch dug across its entranceway soon after the enclosure was created (Williams et al. Reference Williams, Hart and Williams1996, 12). The picture at this site is unclear: the sections of the enclosure (V-shaped) and antennae ditches (U-shaped) appear markedly different, potentially indicating a greater complexity of phasing than was originally discussed in the report and making it difficult to define the site as a true banjo enclosure.

At Micheldever Wood the chronological picture is less clear. Fasham (Reference Fasham1987, 62) argues that the Middle Iron Age occupation took place in the 2nd and 1st centuries bc, towards the end of the Middle Iron Age. However, a review of the illustrated sections in the report suggests the recutting of the ditch in the later phase of use, which he attributed to the Late Iron Age, does not always (if ever) remove all previous fills from the Middle Iron Age phase. The numerous contexts identified in the drawn sections clearly outline the silting of the ditch, which appears to have occurred over a considerable period of time. Fasham does not provide convincing evidence that the enclosure was continuously occupied across the two phases and therefore the filling of the ditches may indicate the site was abandoned for a period of time before being returned to in the Late Iron Age. Additionally, the radiocarbon dates (Fig. 5) provide only a broad Iron Age date from the two pits sampled, offering little insight into the potential phasing and dating of the site. The archaeological evidence remains indeterminate and the report does not detail or outline potential scenarios for each chronological development. This may mean the Middle Iron Age occupation of the site was slightly earlier than previously thought, potentially in the 4th or 3rd century bc.

There are a number of sites where phases of use can be attributed to a slightly later period, broadly the Middle–Late Iron Age transition, and some were in use in the Late Iron Age. At Blagden Copse, Stead (Reference Stead1966) identified a single phase of construction and occupation of the site. He attributed the pottery from the lower fills of the enclosure ditch to the Middle–Late Iron Age transition, probably around the early 1st century bc. Pottery from the upper fills of the ditch was identified as Late Iron Age ‘southern Atrebatic’ (Stead Reference Stead1966, 88). These artefacts may slightly skew the dating of the site, as these contexts may relate to the infilling of the ditches and the ‘closing’ of the site at the end of the Iron Age, as opposed to occupation. A similar practice was observed in the Late Iron Age/Early Roman period at Bramdean (Perry Reference Perry1982, 71).

Surface collection surveys in the 1980s provided additional finds from banjo enclosure sites in the Wiltshire and Dorset region (Corney Reference Corney1989). Casual finds from Hamshill Ditches include Durotrigan coins and Late Iron Age fibulae and pottery (Corney Reference Corney1989, 116). Surveys of the Gussage Hill complex also uncovered a number of Durotrigan coins, Late Iron Age fibulae, and Dressel Ia amphora associated with the six banjo enclosures located there (Corney Reference Corney1989, 120–2). As yet no excavation has taken place there so it is difficult to make too detailed an assessment of the length that these sites were in use, but there was clearly activity relating to either the occupation of or the closing of the site in the Late Iron Age period.

No investigated site has shown continuity into the Roman period. The excavation of Roman sites above or adjacent to banjo enclosures at Beach’s Barn (Harding Reference Harding2007), Grately South (Cunliffe & Poole Reference Cunliffe and Poole2008), and Bramdean (Perry Reference Perry1986) show no signs of site reuse or the re-excavation of the ditches. Furthermore, Nettlebank Copse shows that the area was entirely turned over to agriculture during the Roman period. This is mirrored across the Lambourn Downs where many of the field systems directly overlie, and do not respect the position of, these enclosures. It is therefore apparent that whatever function(s) these enclosures served in their last phase of use, it was not continued following the establishment of Roman rule.

Interpretations

For much of the period in which these sites have been studied, interpretations have been aligned to culture-historical and processualist approaches of the 1950s to 1970s. The location of many Wessex banjo enclosures within the heart of ‘Celtic’ field systems (Perry Reference Perry1974, 71) suggested that they formed an integral part of agricultural practices in the later Iron Age. However, the relatively small size of these enclosures distinguished them from principal farmstead sites. Instead Perry (Reference Perry1974, 71) identified practical characteristics that were indicative of an enclosure closely associated with animal husbandry: an internal ditch that could have been for retention, and a narrow focusing of the ditches at the enclosure entrance that could have been used for funnelling and corralling stock. A gate-type feature was excavated at Bramdean, and reconstructed at Butser Farm (Hampshire) as part of its experimental archaeology programme; it was determined to be most effective as a tool for stock control (Perry Reference Perry1982, 71).

As well as being considered sites for corralling stock, banjo enclosures have also been interpreted as processing sites. Pits at Bramdean, Beach’s Barn, and Micheldever Wood were suggestive of food storage. At Micheldever Wood environmental samples identified numerous weeds indicating initial crop processing took place here (Fasham Reference Fasham1987, 56). The excavation of a shallow flint nodule area at the centre of the Micheldever enclosure was also tentatively interpreted as a threshing floor (Fasham Reference Fasham1987, 63).

The material culture recovered from Micheldever Wood also evidenced other domestic activities. Fasham (Reference Fasham1987, 65) argued that rather than serving a single purpose, Micheldever Wood was a settlement site with additional agricultural functions. The banjo enclosure at Owslebury has also been suggested to be a settlement site (Collis Reference Collis1968; Reference Collis1970; Reference Collis2006), as has Beach’s Barn, which is evidenced by a number of pits visible from the survey and excavation (Harding Reference Harding2007). Thus many of the enclosures have been described as farmsteads: homes with areas set aside for agricultural activities. This remains a favoured interpretation for many such banjo enclosure sites.

It was first possible to challenge this broadly functionalist framework using Hingley’s concept (1984a) of Germanic ‘modes of production’ as an interpretive model of Iron Age societies. Hingley investigated the comparative landscapes of the Upper Thames valley and the Oxfordshire uplands immediately to the north. In the period leading up to his research, the Thames valley had been subject to research, rescue, and commercial excavations almost continuously for over 60 years. These investigations identified large numbers of unenclosed and potentially interconnected or interrelated settlements over large areas of the floodplain and gravel terraces of the Thames (see Lambrick & Robinson Reference Lambrick and Robinson2009). Alternatively, only a relatively small number of enclosed settlements, mostly banjo enclosures, were identified on the limestone uplands. These sites were markedly different to those in the Thames Valley.

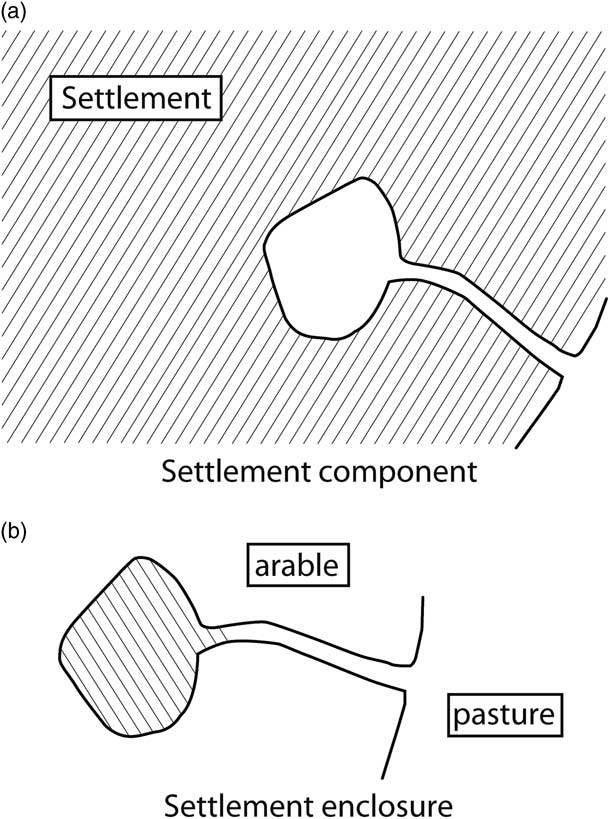

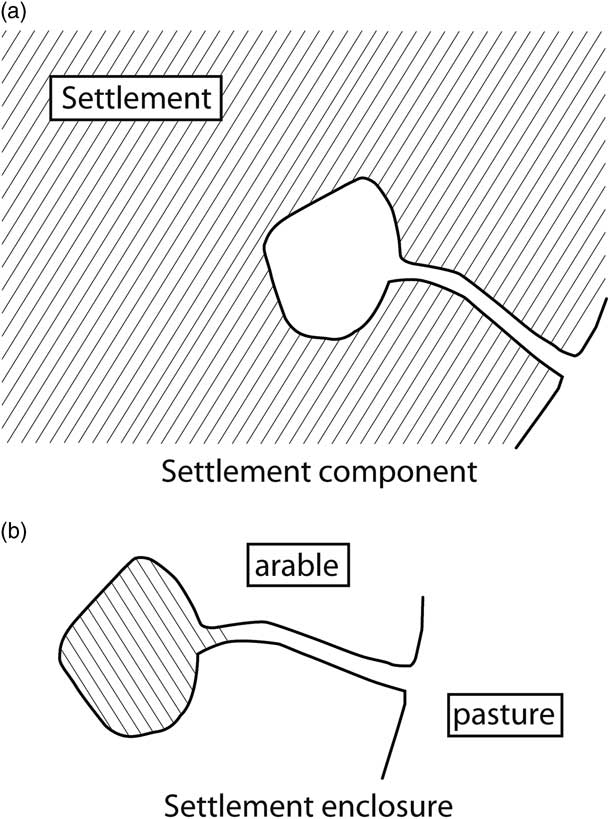

Hingley (Reference Hingley1984b) interpreted these two landscapes as representing two distinct social environments: the open and greatly interdependent settlements of the Thames Valley versus the small, isolated, single family farmsteads that experienced little or no social or material exchange in the uplands. This interpretation was strengthened by the archaeological evidence from the Middle Iron Age in the Thames Valley that showed the development of a number of specialist sites, such as Farmoor or Mingies Ditch, which appeared to solely exploit the specialist resources of the floodplain (Lambrick & Robinson Reference Lambrick and Robinson1979; Allen & Robinson Reference Allen and Robinson1993; Lambrick & Robinson Reference Lambrick and Robinson2009). The reliance on group connections led Hingley to interpret this social space, settlement, and material production as egalitarian. Comparatively, the upland settlement landscape was dispersed, consisting of small enclosure sites practising a self-sufficient, mixed farming economy. The banjo enclosures within these sites acted not only as boundaries for the settlement areas but also as a means of dividing the immediately local agricultural landscape. Pastoral areas were located immediately in front of the funnel entranceway (again implying an agricultural-based function for the banjo enclosure entranceway), and arable landscapes were behind the settlement site away from the pasture areas (Fig. 6). Hingley interpreted these enclosed settlements as developing out of kinship networks and as such they were part of a hierarchical social system potentially based on patronage of items or material now invisible in the archaeological record (Hingley Reference Hingley1984a, 82). This theory of differing social systems pushed Iron Age studies forward by moving us away from interpreting Iron Age sites and societies within solely hierarchical structures and also helping to identify connectivity within wider landscape frameworks.

Fig. 6 Interpretative functions of banjo enclosures by Richard Hingley

Discussions have since advanced as a result of the surveys and excavations that were conducted towards the end of the 20th century. Investigations by Mark Corney and Barry Cunliffe began to emphasise the potential for different functions of banjo enclosures and the activities that took place within them, further unpicking functionalist interpretations of these sites. Corney’s (Reference Corney1989) surface collection review focused on the Late Iron Age finds recovered from the surface surveys on Cranborne Chase, emphasising the sites as being of considerable importance in terms of function and status. The retrieval of high-status or less-common materials such as coins, metalwork, and imported pottery, suggested that their significance had been underestimated. This idea was further explored at Blagden Copse, which Corney (Reference Corney1989, 115) located at the heart of a complex dyke system closely associated with a rectangular enclosure that he interpreted as a local equivalent of a European viereckschanze – a rectangular ditched enclosure often interpreted as religiously significant, sometimes with deep shafts containing significant deposition material (Cunliffe Reference Cunliffe1997, 200). While the religious status of these European sites as ‘cult’ locations has been dismissed (eg, von Nicolai Reference Von Nicolai2009), Corney’s interpretation of banjo enclosures as integral parts of a larger landscape of sites still stands, even if any religious or ritual connotations are less obvious or directly comparable to European equivalents.

Cunliffe and Poole (Reference Cunliffe and Poole2000, 135) have argued that Nettlebank Copse may serve as a potentially stronger example of a banjo enclosure that may have held some form of religious or ritual significance. Analysis of the material culture illustrates that the site’s settlement activity was not associated with the banjo enclosure, which suggests alternative potential functions for the site. The recording of a number of animal bone deposits within the ditches led to the proposal that, in the later phases of use at least, it may have served a more ritual purpose. The site might have been visited at certain times of the year or have been tied in to the annual agricultural cycle. Rather than acting as an area of husbandry, the site itself embodied aspects of farming regimes, possibly leading to its functionality as a mechanism of ritual significance, a place of meeting and feasting within what Cunliffe and Poole considered to be marginal areas of the landscape.

NEW PERSPECTIVES ON FORM AND FUNCTION

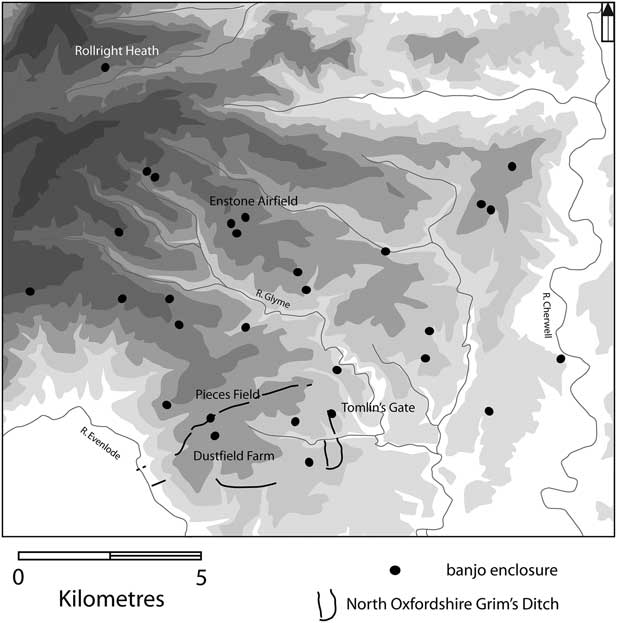

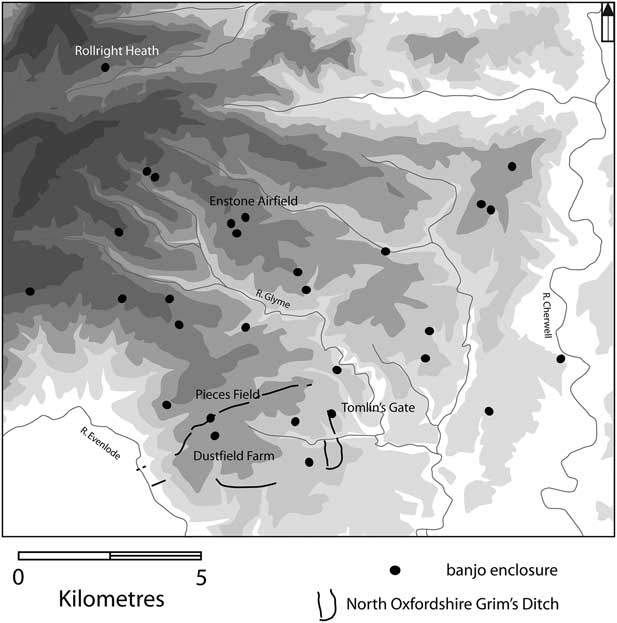

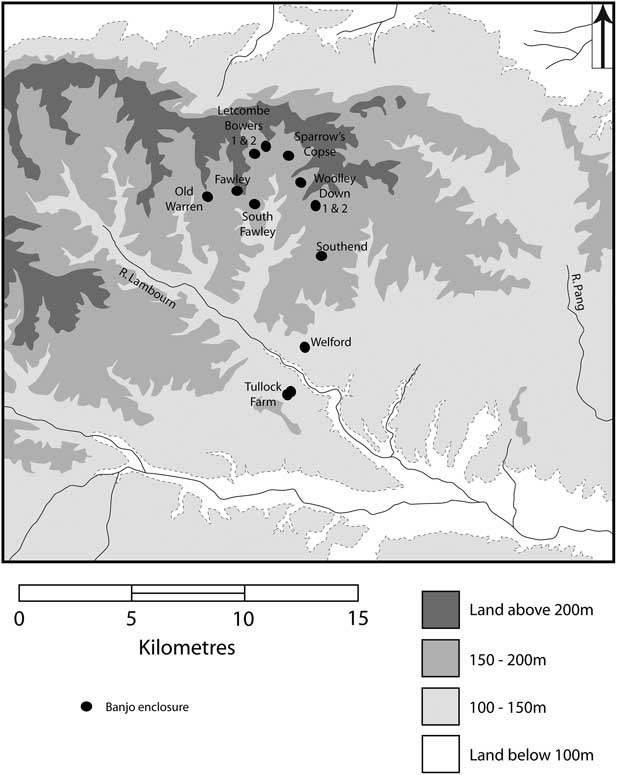

The 1990s marked a turning point in banjo enclosure research. Along with Cunliffe’s excavations at Nettlebank Copse, the Royal Commission commenced aerial surveys in north Oxfordshire, which identified large numbers of cropmark sites including the densest cluster of banjo enclosures in England (Figs 7 & 9.4–9.7; ten sites in Hingley & Miles Reference Hingley and Miles1984; 33 sites in Featherstone & Bewley Reference Featherstone and Bewley2000). This was soon after followed by the National Mapping Programme (NMP) of the Lambourn Downs (Figs 8 & 9.2–9.3; three sites in Richards Reference Richards1978; 12 in Winton Reference Winton2003), which led to further discoveries between the significant clusters of Hampshire and Dorset and the eastern Cotswolds. These discoveries have forged new directions of research through both surveys and excavation. Both of the newly mapped landscapes can be considered classic ‘upland’ regions where banjo enclosures have typically been found in large numbers and have proved favourable to both aerial and magnetometry surveys. The significant increase in site numbers and the detailed mapping of the areas allows us to identify specific features of the sites and add them to the greater corpus of banjo enclosures.

Fig. 7 Distribution of banjo enclosures in the eastern Cotswolds

Fig. 8 Distribution of banjo enclosures on the Lambourn Downs

Aerial surveys have shown that the banjo enclosures of the eastern Cotswolds are extremely varied (eg, Figs 9.4–9.7). Many are irregular in form with shapes and lengths of ditches differing at each site. Some are particularly large (larger than those previously known) and some are associated with other features and wider cropmark complexes. So far none has been identified as being associated with a large-scale field system or linear dyke system; however there are a number in close proximity to the North Oxfordshire Grim’s Ditch (NOGD) (Fig. 7). This intermittent circuit of ditches encloses approximately 1300 ha on high ground above the Evenlode River. It is dated to the Late Iron Age which, in the context of the Cotswolds and Thames Valley, has been persuasively argued to be created within a relatively short period immediately prior to the Roman invasion, approximately ad1–50 (Moore Reference Moore2006; Reference Moore2007a–Reference Mooreb; Booth et al. Reference Booth, Dodd, Robinson and Smith2009). While it has drawn comparison with other Late Iron Age complexes, the ditch complex is unique in British archaeology. At least five or six banjo enclosures (and a number of likely Iron Age rectilinear and curvilinear enclosures) are located in close proximity to the Late Iron Age circuit of the ditch complex. The relationship between the NOGD and the banjo enclosures nearby provide the best evidence of settlement within a circuit. The location of two enclosures, Tomlin’s Gate (Hingley Reference Hingley1982; Fig. 2.6) and Pieces Field, Ditchley (Fig. 9.7), also provides at least some indications of phasing. The Tomlin’s Gate enclosure is located at the crest of a hill with the ditch circuit below it following the contours of the hill. It is more likely the banjo enclosure was constructed first as the circuit of the ditch and respected the existing banjo enclosure. At Pieces Field, Ditchley the ditch circuit is on the crest of the hill and the banjo enclosure 100m north, slightly below it. Therefore, the enclosure was constructed after the ditch, potentially respecting its course.

The Lambourn Downs enclosures (Figs 9.2–9.3) also vary in form, and the quantity and type of activities evidenced by their pits and linear features. These have been associated in the past with the so-called Celtic fields of the region, further suggesting that they functioned as farmsteads. Due to further investigation, reinterpretation, and a better understanding of the chronology of field systems found to be Roman in date, their function as farmsteads has been questioned and subsequently dispelled (Ford et al. Reference Ford, Bowden, Mees and Gaffney1988; Winton Reference Winton2003; Lock et al. Reference Lock, Gosden and Daly2005). As with the eastern Cotswolds, certain features in the landscape proved important. Surveys of the enclosures showed that they were all positioned at the head of river valleys (now dry) and that the funnel entrances were aimed towards the valley bottoms (Bewley Reference Bewley2003).

Excavations have also provided new perspectives on research. Three sites have recently been excavated by researchers at Rollright Heath, an enclosure within the Bagendon complex (Gloucestershire), and at North Down, Winterborne Kingston in Dorset. A further site (Caldecote Cambridgeshire; Fig. 2.1) is one of a small number of sites known in the East Anglia region. It underwent an almost complete, development control-led excavation, which revealed three phases of occupation of the banjo enclosure, all dated between c. 100–75 bc and ad 50. In this instance, the pottery identified from internal features suggests that these may have pre-dated the digging of the enclosure ditch (Kenney & Lyons Reference Kenney and Lyons2011, 67), much in the same way as Nettlebank Copse. On two further occasions the ditch was redug; it sustained a relatively long period of abandonment between the creations of the first and second ditch before the site was closed at the end of the Iron Age (Kenney & Lyons Reference Kenney and Lyons2011, 70).

The excavations at Rollright Heath revealed multiple phases of use: a pre-‘banjo’ enclosure, the banjo enclosure itself, and then closure and abandonment. Initial analysis indicates that the site was probably occupied during at least the last century of the Iron Age. Early in the Roman period, the site was ‘closed’ by burning material across it (a number of fire pits were identified) and depositing it in the enclosure ditches to level the site. A double ditched, square enclosure was constructed at the same time, with one return crossing the enclosure entranceway, representing a deliberate action in closing the site. North Down provides an alternative picture. Excavations by Miles Russell and Paul Cheetham have provided evidence for a relatively late date of the site with little evidence of pre-banjo occupation. The site was abandoned before the end of the Iron Age, and was later used as a Late Iron Age Durotrigan cemetery (Russell & Cheetham pers. comm.).

Re-categorisation

These relatively recent discoveries have provided evidence of a number of additional features that are helping to redefine our understanding of banjo enclosures. Sites such as Dustfield Farm (Oxfordshire; Fig. 9.6) and Heathcote Home Farm (Warwickshire; see Gaffney & Gater Reference Gaffney and Gater2003, 129, fig. 63) have small annexing enclosures often either joined to or immediately adjacent to accompanying linear features. And we can now say that banjo enclosures regularly contain large numbers of pits across the interior. Whilst this is not uncommon for Iron Age sites, a recurring characteristic that has been identified through a number of geophysical surveys is that pits will often internally mirror the course of the enclosure ditch in a short-form pit alignment. Examples from North Oxfordshire include sites such as Pieces Field, Ditchley (Fig. 9.7) where geophysics highlighted significant numbers of pits following the course of the north-east quadrant of the enclosure ditch. Features such as these also potentially indicate that many sites had an external bank rather than an internal one.

The surveys described above have added to our two-dimensional understanding of form but as yet they do not allow us to re-categorise or redefine these sites in any detail. These enclosures range in shape, size, and antennae ditch length as well as their association (or lack thereof) with other enclosure sites in the landscape. Furthermore, our broader understanding of banjo enclosures remains problematic. The term itself is a catch-all, often hiding very different site forms, distinctly different landscape sitings, and potentially varied functions. Added to this, authors have often used different type-sites to categorise banjo enclosures, which has resulted in confusing definitions. As Perry himself argued, terms, such as ‘banjo enclosure’ are subjective by their very nature. There has often been a tendency to place cropmarks within categories such as size (eg, Palmer Reference Palmer1984) or form. This has sometimes led to overly complex divisions based on local differences, rather than defining them within regional or national contexts.

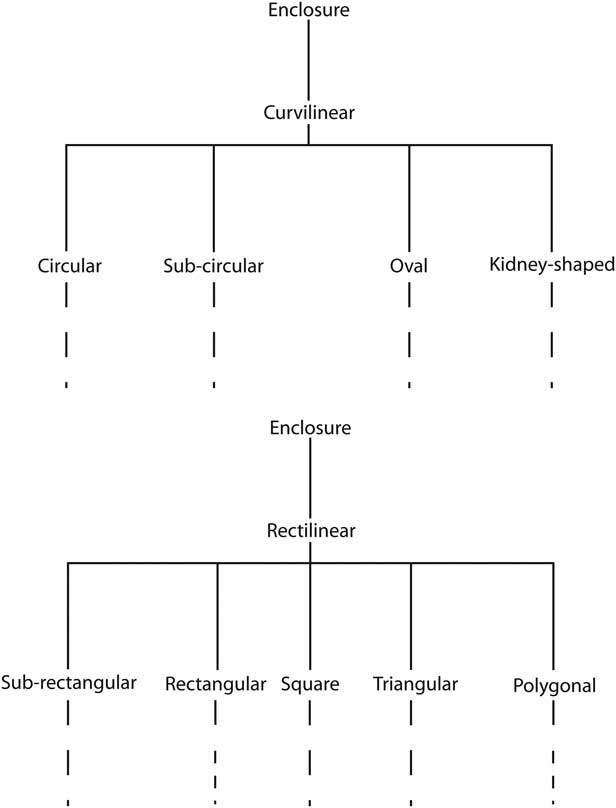

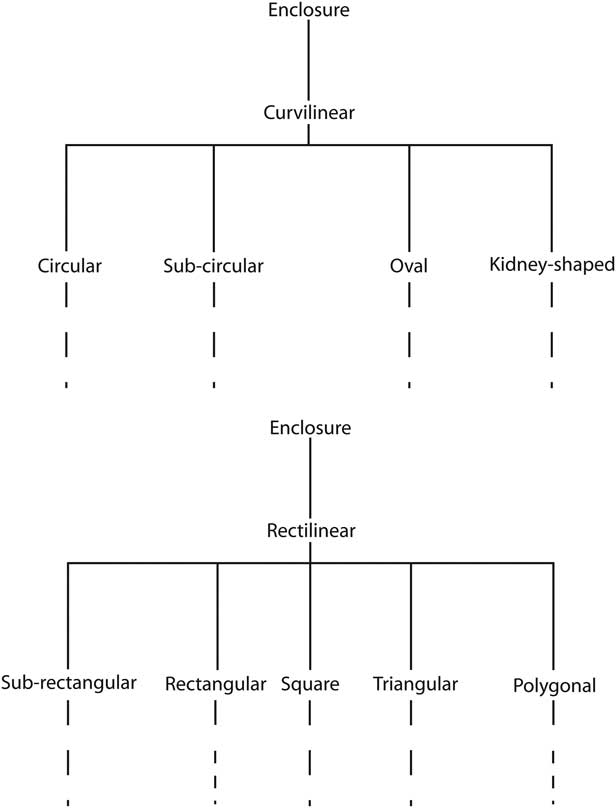

There is therefore an opportunity to simplify our system of analysis of these sites. Although it may be simpler to abandon the term banjo enclosure, given its widespread use it may be more fruitful to provide a more simplistic system of descriptions which is less subjective than that provided by Perry and the MPP. A more refined system of analysis requires generating more objective descriptions, stripping away terms currently in use, and then broadening categories of form. For banjo enclosures, it is best to simply define them as either curvilinear or rectilinear enclosures. These two terms are adapted from the Royal Commission’s original classification scheme (Edis et al. Reference Edis, MacLeod and Bewley1989), which formed the basis of the MORPH system used in early NMP projects and was subsequently updated as these programmes developed. Curvilinear enclosures include circular, sub-circular, oval, and kidney-shaped forms; rectilinear enclosures include rectangular, sub-rectangular, square, triangular, and polygonal forms. The breakdown of these classifications can be seen in Figure 10.

Fig. 9 Examples of banjo enclosure forms from central southern Britain. 1: Gussage All Saints, Dorset (after Barrett et al. Reference Barrett, Bradley and Green1991, 235, fig. 6.4); 2: Letcombe Bowers, Berkshire (after Winton Reference Winton2003, 16, figs 1.4 & 1.7); 3: Sparrow’s Copse, Berkshire (after Winton Reference Winton2003, 16, figs 1.4 & 1.7); 4: Rollright Heath, Oxfordshire (after Historic England unpublished aerial photo rectification); 5: Enstone Airfield, Oxfordshire; 6: Dustfield Farm, Oxfordshire; 7: Pieces Field, Ditchley, Oxfordshire

Fig. 10 Proposed aerial photographic forms for banjo enclosures

Using broad categories of form within this classification system will better incorporate future finds that may be irregular, while also including irregular sites already discovered, without adhering to rigid descriptions. Using additional features such as size, landscape setting, or associated features affords us greater descriptive license without fixating on whether or not the site constitutes a banjo enclosure. We can therefore move away from considering these sites individually and instead view them as a wider grouping of Middle and Late Iron Age enclosures.

Interpretations

More recent surveys and excavations of banjo enclosures have highlighted the necessity of excavation for providing more complete pictures of these sites. The excavations at Nettlebank Copse are a good example of this (Fig. 11); they have contributed to our understanding of banjo enclosures in three key ways. First, the banjo enclosure is not necessarily the only manifestation of activity on-site. Second, the banjo enclosure is not necessarily the most important phase of use. Third, there may be very different functions for the enclosures when they exist as banjo enclosures, either during different periods of use or particularly if the site is abandoned, falls out of use, or is revisited generations later. This time depth has altered our interpretation of these sites and their context within later Iron Age studies. It acts as a salient reminder that even though banjo enclosures are relatively widespread within southern Britain we cannot base their chronology and function on landscape context and form alone.

Fig. 11 A stylised chronological interpretation of Nettlebank Copse, Hampshire

Interpretations have also become more complex regionally. The increase in the number of sites identified within north Oxfordshire make it less likely these sites were isolated farmsteads as described by Hingley. Instead, they are more likely one indicator of a wider population choosing to define their landscape through enclosure – this is less a symptom of isolation but, instead, one of expression. The population still participated in a wider exchange of goods stretching from the Severn to the Thames valleys (Moore Reference Moore2007c). More recently, Moore (Reference Moore2012) has suggested that many of the banjo enclosures identified within larger complexes are just one aspect of ‘polyfocal’ complex sites. He argues that at locations such as Bagendon (Gloucestershire), Gussage Hill, and those within and around the North Oxfordshire Grim’s Ditch, banjo enclosures potentially served one function within a larger complex of sites. Along with the other enclosures, ditches, and activity locations these sites and complexes developed as landscapes, formalising movement within the landscape and acting as indicators and representations of power (Moore Reference Moore2012, 413). These sites and complexes existed throughout southern Britain and within the Late Iron Age of the region are potentially representative of the shift towards more complex settlement landscapes, which are best identified through nucleated settlements and linear dyke systems integrating settlement and funerary landscapes. Though this is a convincing argument, the potential phasing of the banjo enclosures located close to the North Oxfordshire Grim’s Ditch adds complexity to the phasing of a potential ‘polyfocal’ enclosure. Here banjo enclosure sites probably appeared before and after the ditch system was created. We may be seeing an evolving Iron Age landscape developing over at least one or two centuries rather than the rapid appearance of multiple sites simultaneously.

CONTEXT AND COMMUNITIES

The appearance of banjo enclosure sites in Britain during the 4th century bc represents just one of a number of changes to patterns of settlement, types of sites, and the focus of activities in the Iron Age. In some ways banjo enclosures are representative of the changes seen in southern and midland Britain and certainly act as markers of it; however, in the past too much emphasis has been placed on the functional aspects of these sites and therefore they have been viewed in partial or complete isolation. Recent excavations of sites and the development of multiple interpretive frameworks now allow us to outline a more holistic approach, not only for interpreting each phase of a site but also their context within local, regional, and national landscapes, and within wider Iron Age studies.

The beginning of the Middle Iron Age marks a time when there is far greater emphasis on the enclosure of space and location, a topic that has been discussed at length in Iron Age studies (eg, Bowden & McOmish Reference Bowden and McOmish1987; Collis Reference Collis1996; Reference Collis2006; Hingley Reference Hingley1990; Thomas Reference Thomas1997; Moore Reference Moore2007a). From one perspective, banjo enclosures represent a unique expression of bounded space in the Iron Age. Where it can be proved, the position of the bank outside of the ditch is likely to indicate a manifestation of display or status, not defence. The banks concentrate focus on the interior, perhaps partially blocking the visibility of the immediate environs except down the narrow focus of the funnel entranceway. The ditches do not necessarily need to be the depth or width that they are in order to fulfil their purpose, indicating that they were more than just functional. The sites show limited use: abandonment is represented by ditches that were left to silt naturally or were filled in within a very short space of time. This behaviour is similar, superficially at least, to many pit deposits of the time (Hill Reference Hill1995). The ‘blocking’ and ‘closing’ of enclosures also appears to be an articulation of abandonment and may well represent a final act of enclosing the space contained by these sites. In some cases banjo enclosures were occupied relatively long-term (eg, Micheldever Wood); at others they were quickly closed and either a new site was constructed in a different form (eg, Owslebury) or the site was abandoned and later served an entirely different purpose (eg, Nettlebank Copse).

The variety of these enclosures demonstrates their potential local and regional differences. Aspects such as shape, size, and length of entrance, orientation, and topographical and geographical location have all been used to support various interpretations. A good example of this is the diversity of funnel entrances. These range in length from 15 m (eg, Bramdean) to 85m (eg, Rollright Heath); does this mean that these entrances were dug for different reasons? A short entranceway would serve suitably for funnelling and dividing livestock such as sheep. If the site served a purely practical function it is likely that the people using the site would exert as few labour hours as possible to create and upkeep the site; it is less likely that time and energy would have been exerted on an elongated funnel entrance if there was not a required function or purpose. Alternatively, elongated or complex antennae ditch entrances might relate to ceremonial pathways or high-status entrances intended to show how much effort was exerted in creating the site. It is therefore reasonable to argue that sites with different entrances served different functions. The width or position of the banks might also be a factor. A narrow, elongated entranceway might enhance or exaggerate a feeling of enclosed space or a set direction that must be followed, whereas wider entrances or lower banks might enable a less restricted view of the surrounding landscape.

Within the Wessex region banjo enclosures represent a new type of enclosure that emerged in the Middle Iron Age. They joined the corpus of enclosures such as household/farmstead-type enclosures already known in the Wessex region from the Early Iron Age. Banjo enclosures vary in terms of their location and proximity to other enclosure complexes. In most instances, it can be argued that they mark some form of change to sites already occupied. Previous occupation is known at many excavated sites, and the changes that occurred concurrently with the creation of banjo enclosures mark the development of the site from either an open one (or perhaps temporarily enclosed through organic materials) to an enclosed one.

The association of banjo enclosures with complex sites of multiple enclosures (banjo or otherwise) also suggest that these sites fit within a wider trend of transformation of the settlement landscape. On the other hand, they may form just one part of change and development to settlement complexes. Sites such as Owslebury fit within the wider complex development, even if the enclosure itself quickly fell out of use. Another example, Nettlebank Copse, presents a different evolution. It appears to follow a similar development to other associated sites until the point at which the enclosure ditch was initially excavated, but soon after it appears that the ditches were no longer considered useful or relevant and its function changed entirely.

Comparatively, in areas such as the Cotswolds and Lambourn Downs, banjo enclosure sites are part of a wider pattern during the Early–Middle Iron Age transition. At this time we see the widespread appearance of enclosed spaces, either through enclosures (Hingley & Miles Reference Hingley and Miles1984; Moore Reference Moore2007a) or households (Allen et al. Reference Allen, Miles and Palmer1984; Moore Reference Moore2007b). This potentially marks a rise in territoriality, probably as a result of increased population size and specialist exploitation of the landscape. Interpretations proposed by Lambrick and Robinson (Robinson & Lambrick Reference Robinson and Lambrick1984; Lambrick & Robinson Reference Lambrick and Robinson2009) have persuasively argued that upland landscapes surrounding the Thames valley were only fully settled and exploited during the Middle Iron Age. It is likely at least some of the banjo enclosures within this region date to this period of widespread landscape change. It is equally likely that at least some of these sites date towards the end of the Iron Age, although we have yet to fully understand the relationship of banjo enclosure sites to the Late Iron Age North Oxfordshire Grim’s Ditch. It is apparent that some of these sites were in use during the period and formed one of Moore’s (Reference Moore2012, 405) ‘polyfocal’ complexes. If so, this area would have been a large-scale settlement landscape in use immediately prior to the Roman invasion.

Previously our interpretations and investigations have explained these enclosures in very singular terms. The phasing is often the initial occupation of a site, followed by the construction of the banjo enclosure and, finally, abandonment. In excavation and interpretation terms the middle phase, that of the construction of the banjo enclosure, is the most significant. Interpretations have depended on the results of excavation from the banjo enclosure and the material remains therein. These enclosures were often seen as sites with a long-term focus where typically each was representative of one function.

There can be no doubt that banjo enclosures served different functions. Some clearly show evidence of settlement or agricultural practices, and some a mixture of the two. Yet even these enclosures cannot be easily grouped, as they did not serve these functions contemporaneously. Banjo enclosures were also used as locations in the landscape that were visited at certain times of the year or were abandoned for long periods of time. Some were occupied for short periods, as short as a generation, and others for long periods, perhaps 100 or 200 years. Too often these sites have been identified as being contemporaneous in a wider landscape and the detail above has shown that in most examples this is not the case.

The diversity of enclosure size, form, entrance type, length, and location in the landscape clearly indicates that these sites were constructed for, and served, a number of different purposes. Some of these purposes are outlined below.

1) Agriculture. Archaeological evidence provides good examples of crop storage and processing and probably animal husbandry. The enclosure itself would have served as a suitable corral for animals. In a number of cases the funnel entrance – which may have been a gateway – and a divided interior would have served as an excellent stock handling system similar to the one at Storey’s Bar Road in Flag Fen (although this is slightly earlier in date than most banjo enclosures; Pryor Reference Pryor2001, 417–18). Internal divisions identified in a number of cropmark sites may be indicative of this kind of usage. The appearance of pits and possible flint nodule ‘threshing’ floors are also potentially indicative of storage and processing functions for at least some of the lifespan of the site.

2) Settlement. Some sites have produced evidence of settlement, including roundhouses or significant quantities of domestic wares. The small size of the enclosure would have only served a single-family unit and potentially immediate family. The position of these enclosures within wider complexes may also be indicative of separate spaces or locations for living/working/processing. A site such as Hamshill Ditches may present an excellent example of this.

3) Ritual/religious. The excavation of Nettlebank Copse showed that banjo enclosures often fall outside the typical interpretive framework for Iron Age enclosures. The site was quickly abandoned after construction, only returned to years later, and holds no convincing evidence of settlement or long-term/regular storage/corralling activity. In large part their functions remain unknown or can be only broadly suggested. However, the potential for a number of sites with external banks/internal ditches suggests possible religious practices mirroring those of much earlier ancestors; Cunliffe and Poole (Reference Cunliffe and Poole2000, 135) suggest that they may be location points visited for specific purposes such as animal slaughter. It also seems likely that elongated entranceways were indicative of status; they impacted on the landscape more so than a functional gateway or funnel entranceway. Some of these sites were deliberately ‘closed’ by cutting a ditch across the entranceway, either during the Iron Age or at the end of the period, which may also indicate that activities on these sites were deliberately brought to an end or their purposes were no longer deemed necessary.

4) Landscape management and power representation. Moore’s suggestion that some of these sites formed just a single part of multiple, complex landscape networks of enclosures and dykes during the Late Iron Age is intriguing. This may also highlight the possibility that these sites served both individual functions within a larger complex, and were also representative of one major function of a more formal landscape at the end of the Iron Age. Questions remain as to what purpose these individual sites served and for how long, and whether these purposes changed during the course of their use. Moreover, it is not known how they fitted within the system of landscape management, or if they were representations of power. However, it helps to identify the sites that may have served multiple functions at any one time, particularly when there is more than one enclosure within a ‘polyfocal’ complex.

One clear element that appears to link many of these (excavated) sites together is their lack of continued use into the Roman period. At sites such as Grately South, Bramdean, and Nettlebank Copse the sites appear to have been abandoned and later settlements were either built directly on top or close by, or the area was turned over to agricultural land. In many instances there appears to be no recognition of the site that was previously located there. This discontinuity is starkest at Rollright Heath where the destruction of possible buildings, the use of material for infilling and levelling the enclosure ditch, and the position of the early Roman enclosure ditches through the enclosure entranceway signify a deliberate replacement of the previous site. These actions represent a dramatic closing of the site, marking the end of the life of the enclosure. As yet there is no evidence of the use of banjo enclosures within the Roman period, and it appears, for now at least, that these sites remain a wholly Iron Age phenomenon.

CONCLUSIONS: NEW PERSPECTIVES AND FUTURE RESEARCH

This paper has attempted to review and redefine our understanding of what remains a relatively unknown and understudied group of Iron Age sites. On the one hand there exists a relatively large (and still increasing) dataset of cropmark and geophysical surveys; on the other hand evidence from excavation remains comparatively slight. These sites represent a diverse yet singular group of enclosures appearing across a range of landscapes with significant variation in their context, association with other features, phasing, and chronology.

In the past, interpretations regarding their function have focused on aspects such as topography, orientation, and possible relationships with the immediate environs. These interpretations have been too narrow in their observations; perhaps because it has been immediately accepted these enclosures all served the same function. However, it is hoped that this paper has questioned this approach. Sites where the term ‘banjo enclosure’ has been applied represent a broad range of enclosures. By simplifying how we identify and interpret these sites, and going beyond the minutiae of site comparison, we are better able to evaluate them against the wider changes that occurred during the Middle and Late Iron Age periods. This is hopefully a first step to developing a better framework for classification and dating.

This paper offers only partial answers to some interesting problems. The evidence gathered from excavation is imbalanced in favour of one particular region and, even then, the results provided do not offer one simple interpretation. The differences between these sites in material remains, complexity, and phasing do not lead to a single interpretation. This paper has therefore tried to suggest that more than one interpretation exists for these sites, and the evidence should be taken site-by-site, rather than region-by-region.

A considerable amount of research is required before many of the questions relating to these enclosures can be answered. In particular, aspects of function, chronology, absolute dating, use and abandonment, and location and context within wider land-use patterns remain high level questions for these sites. On an individual scale it is important that excavations are undertaken without too much emphasis on other interpretations already put forward. Fortunately, considerable research is ongoing outside of the more heavily excavated Wessex region and this work is sure to add to the dataset. The future publication of these sites will provide useful assistance when it comes to reassessing and reinterpreting these sites and fully understanding their context within the Middle and Late Iron Ages of southern Britain.

Acknowledgments

This paper started out long ago as a submission to an Iron Age Research Student Symposium (IARSS) but it has been redrafted and rewritten many times since then. Considerable thanks must go to all the people who provided comments on it, were willing to talk about banjo enclosures generally, or were subjected to talks about them at various times. This paper has perhaps been rather too long in gestation and I can only apologise to those people that have seen it in its various draft forms. Special thanks must go to Jody Joy and Tom Moore for providing detailed commentary, the editors for all their hard work, and the three referees who provided generous and constructive feedback. Paula Levick, Miles Russell, Paul Cheetham, Kenney Scott, and Elizabeth Popescu at Oxford Archaeology East are all thanked for providing details of their ongoing research and excavations. Thanks must also go to Hugh Coddington for those first discussions regarding banjo enclosures many years ago and Susan Lisk at Oxfordshire HER for continued support throughout various research projects; to Richard Hingley, John Collis, John Creighton, Gill Hey, and George Lambrick for discussions at various times about banjo enclosures, and to Barry Cunliffe and Melanie Giles as supervisor and external examiner respectively of my DPhil Thesis who provided much support and assistance. Peter Bray is happily and fully acknowledged for his much needed assistance with the recalibrated radiocarbon dates. Considerable and heartfelt thanks must go to my family for their support, to Zi for her patience and good humour, and to Hertford College and the Institute of Archaeology at Oxford for their financial support. Finally, thanks must go to Duncan Sayer, without whom the excavations at Rollright Heath would never have become reality. His effort over the Summer of 2010 along with the resources he provided from the University of Central Lancashire were incredibly generous and he is gratefully acknowledged for his support along with Mac, and all the UCLan (and extraneous) diggers for making it all possible.