Neolithic and Bronze Age settlement sites in Britain and Ireland have, on occasion, been identified as being prehistoric villages. Some sites, such as Skara Brae on Orkney or the Bronze Age phase at Jarlshof, Shetland, have been long associated with this term but the application has, to some extent, been used uncritically (Childe Reference Childe1931; Hamilton Reference Hamilton1956). In some instances, particularly relating to older excavations, it is difficult to see the justification of the use of the term ‘village’, and some authors seem to have used it to describe sites best regarded as small hamlets and large farmsteads.

More recently there has been an trend in British archaeology to emphasise the ‘otherness’ of the prehistoric period. Under this regime the use of the term ‘village’ has only been applied very cautiously in discussions of prehistoric settlement. Recently excavated sites that have been referred to as villages include the settlements at Durrington Walls in Wiltshire, Barnhouse on Orkney, and Ronaldsway Airport on the Isle of Man (British Archaeology 2008, 7; Jones & Richards Reference Jones and Richards2005a; Parker Pearson et al. Reference Parker Pearson, Pollard, Richards, Thomas, Tilley and Welham2006). However, other sites, where the overall number of buildings is similar, or even higher, such as the Neolithic settlement at Mullaghfarna, Co. Sligo, or the hut circle groups at Carn Dubh, Moulin, Perthshire, have not been identified as villages. In these cases different settlement types are envisaged, with explanations such as seasonal or successive occupation, defensive retreats, or periodic religious assemblies being preferred (Grogan Reference Grogan1996; Rideout Reference Rideout1995). This paper attempts to provide a simple and usable definition of the village, and to examine whether settlements from the Neolithic and Bronze Age periods of Britain and Ireland can be identified as such.

Defining Villages

The first contentious issue when attempting to identify prehistoric villages revolves around our contemporary understanding of the term and its particular cultural connotations. Within Britain and Ireland villages are intimately linked to narratives concerning the origins and development of the modern nations, stories of immigration, conquest, population replacement, and land re-organisation.

Detailed discussions of the development of villages are most numerous amongst historical geographers and landscape archaeologists, and only occasional mentions of prehistoric villages are found in such texts (Rowley Reference Rowley1978, 60–3). These discussions principally focus on the origins of villages in the Late Saxon and early Norman period, and even then there is little agreement as to what are the essential characteristics of a village (Aston Reference Aston1985, 82; Taylor Reference Taylor1979, 84–90, 103; Rowley & Woods Reference Rowley and Wood2000, 6). This explicit linking of the origins of villages to the formation of England during the medieval period finds expression elsewhere, such as the marketing of the reconstructed Saxon settlement at West Stow in Suffolk, as the ‘first English village’, or the numerous volumes extolling the beauty and cultural importance of the ‘English’ Village. In her poetic tribute Cobb even dismisses villages from northern Britain for being ‘grim in the extreme’ and concentrates exclusively on southern and midland England as the home of the ‘correct’ sort of village (Cobb Reference Cobb1945). In light of the nationalistic flavour of this dialogue it is hardly surprising to find that villages are often considered to be scarce across Ireland as a whole. A less nucleated settlement pattern is often emphasised and villages are generally seen as a late introduction to the country by the Anglo-Normans (Barry Reference Barry1988, 345–6).

There should be serious concerns over the Anglo-centric nature of these discussions of the village and the geographical and chronological constraints they impose. Unfortunately it seems that this has led to the development of a circular argument where the prehistoric period is concerned, and serious enquiries regarding the existence of prehistoric villages have not taken place because they are so widely regarded as a medieval development. Given this absence, a particularly important study is Flatrés’ wide ranging investigation of rural settlement across western Europe in the mid-20th century (Flatrés Reference Flatrés1971). Despite getting entangled by problems of nomenclature, Flatré concludes there is a repeated occurrence of clustered rural settlements of over 20 houses or 50 inhabitants in most regions that, for general purposes, can be identified as villages. He also highlights the extreme degree of variation demonstrated across this large region, especially in regard to the patterns of dispersal and nucleation present within a settlement that was self identified as a single entity (ibid., 165–70). A similarly simple and inclusive concept of the village was used by Roberts in his examination of the myriad forms of settlement found in different parts of the world (Roberts Reference Roberts1996).

Size Matters!

The most important factor in determining if a settlement should be classified as a village must surely be the size of the settlement, as reflected by the number of contemporary households. Simple definitions of what constitutes a household can also be elusive. Sørensen's notion of the household as ‘a group of people who live together most of the time and who, between them, share the activities needed to sustain them as a group’ seems sufficient for the purposes of this study (Sørensen Reference Sørensen2010, 123). The relationship between the number of buildings in a settlement and the number of households is not necessarily straightforward, as in some instances a household may equate to a single building or to a small number of associated buildings, whilst in others a single large building may have been occupied by multiple separate households. Identifying such a group archaeologically can be challenging, but the discrete clustering of buildings within a larger group, or the presence of connected buildings within a larger group, are used as the key indicators.

The exact number of households that should be present within a settlement for it to be classified as a village is difficult to determine. The settlement size should be large enough that the term ‘hamlet’ can be seen to be inappropriate. It is suggested that Flatrés’ figure of 20 independent households seems large enough to justify the designation, but rather than a sharp boundary below this number, there is a hazy blurring with the upper size range of the hamlet. The difference between a large hamlet and a small village is probably rather meaningless in the real world; the word hamlet derives from the Old French hamel, meaning little village.

The need to establish the internal chronology of a settlement presents serious difficulties for archaeological fieldwork and small scale excavations and field survey may do little to illuminate this potentially complicated area. Even during large scale excavation, problems can arise. Dutch archaeologists refer to the ‘wandering house’, where small scale settlements periodically re-occupying the same location leave an archaeological imprint that is very difficult to distinguish from a larger settlement where multiple buildings were occupied simultaneously (Fokkens & Arnoldussen Reference Fokkens and Arnoldussen2008, 3–4). Similarly a small settlement occupying roughly the same location over a prolonged period may prove problematic in the absence of changes to the design of the buildings, the superimposition of later building footprints over earlier ones, or artefact assemblages that can be used to trace the development of the settlement over time. Such difficulties can only be conclusively overcome when a large number of structures have been closely dated by absolute dating, through artefacts with a very tight and well understood chronology, or by the presence of physical traits such as interconnecting paths or conjoining artefacts that clearly demonstrate simultaneous occupation.

Indelible Blots on the Landscape

The question of whether a settlement is permanently occupied or one where occupation is limited to a particular part of the year is also an important issue. The familiar concept of the village implies permanent year-round occupation. Seasonally occupied sites, such as transhumant settlements or the encampments of nomadic herders, are generally excluded from being considered as proper villages (Cribb Reference Cribb1991; Rathbone Reference Rathbone2010). Numerous authors have suggested that specific Neolithic and Bronze Age sites should not be considered to be villages because they were only seasonally occupied. This argument is principally applied either when sites are associated with religious complexes or because they are perceived as being located in inhospitable hilltop locations. Whilst it is accepted here that a village should be occupied by at least part of the population during the whole year, it is acknowledged that this is a rather tenuous proposition and one that could be usefully examined in more detail than space allows here. Caution must also be used when considering the duration of an occupation. There is no reason to exclude sites that were only occupied for a few years or which were abandoned and returned to sporadically; such ideas about the permanence of a village relate too directly to notions of the medieval and later villages and need not apply to prehistoric examples.

The association between seasonal occupation and settlements adjacent to religious sites is problematic, especially when considering Neolithic sites. In North Mayo and the Burren, Co. Clare, rather more complete examples of Neolithic landscapes have been recorded than is typically the case. In both of these areas it can be seen that an integrated landscape existed which contained settlements, field systems and religious sites, and there was no particularly marked spatial separation of the secular and profane (Caulfield et al. Reference Caulfield, Warren, Rathbone, McIlreavy and Walsh2009a; Jones Reference Jones2003). This association between settlements and religious sites is also repeated in the Late Neolithic of Orkney, for example at Barnhouse, Rinyo, and Wideford Hill (Garnham Reference Garnham2004, figs 4 & 40). These examples show that there is no reason to simply assume that settlements should be set at some remove from religious sites, and religious buildings and burial grounds are a frequent feature of villages from many periods and regions.

To the modern eye, upland locations generally appear bleak and inhospitable, even whilst their rugged charm is appreciated. When potential settlement sites are viewed in upland locations they are often claimed to be suitable for seasonal occupation as they are too exposed to be inhabited in the winter. Such claims seem to be largely based on modern preferences and need not apply to either the Neolithic or Bronze Ages, especially as the climate and vegetation may have been different than at present (Ashmore Reference Ashmore1996; Overland & O'Connell Reference Overland and O'Connell2009, 320–2; Quinnell Reference Quinnell1994). O'Brien has recently highlighted that the uplands of Ireland are not particularly high, and this comment is also applicable to most of Britain (O'Brien Reference O’Brien2009, 1). The highest village currently occupied is Wanlockhead in Dumfries & Galloway at 466 m, closely followed by Flash in Staffordshire at 460 m, both considerably higher than many prehistoric sites that have been claimed as being unsuitable for permanent occupation on grounds of altitude. Many prehistoric sites in upland locations were clearly suitable for large populations for at least some part of the year, and during what must have been lengthy periods of construction. Suggested problems, such as lack of water supply and exposure, must therefore have been surmountable for those periods so it is at least possible they were surmountable for the duration of the year.

Neolithic Villages: The Probable's and Probably Not's

For much of Britain there is a perceived absence of domestic buildings of Neolithic date. Where plans of structures have been identified the function of the buildings has been interpreted in a wide variety of ways, with numerous authors suggesting non-domestic uses for these structures (Cross Reference Cross2003, 195–202; Loveday Reference Loveday2006, 75–87). The number of known Neolithic buildings has increased slowly, but the situation regarding the nature of Neolithic settlement remains rather obscure for most regions. Where settlements have been identified the predominant pattern identified is one of isolated farmsteads and the smallest of hamlets (Darvill Reference Darvill1996; Barclay Reference Barclay1996). Detailed reviews of Neolithic settlement patterns indicate that no village-like settlements are presently known from midland and northern England, mid- and north Wales, lowland and highland Scotland, the Western Isles, or Shetland (Armit Reference Armit1996; Barclay Reference Barclay2003; Calder Reference Calder1956; Darvill Reference Darvill1996; Ray Reference Ray2007).

A reasonable number of substantial rectangular timber buildings have been excavated in Ireland, either found in isolation, as at Mullaghabuoy, Co. Antrim, or in very small groups, as at Coolfore, Co. Louth (McManus Reference McManus2004; Ó Drisceoil Reference Ó Drisceoil2003). Recent analysis suggests that these rectangular structures may date from a very restricted time frame in the Early Neolithic, and a far more amorphous style of small irregular oval and circular buildings seem to be present during the rest of the period (Caulfield et al. Reference Caulfield, Warren, Rathbone, McIlreavy and Walsh2009b, 17–19; McSparron Reference McSparron2008; Grogan Reference Grogan1996, 59). In Ireland it is commonly taken as self-evident that these rectangular buildings represent farmsteads, as opposed to the less mundane explanations often used to explain fundamentally similar buildings in Britain. The reasons behind these different interpretative stances have been well reviewed by Cooney (Reference Cooney1997, 23; Reference Cooney2003).

The only substantial Neolithic settlement known from central southern England is the recently discovered site inside Durrington Walls in Wiltshire. Initial reports described the presence of over 20 simultaneously occupied structures of Late Neolithic date found at the famous Wessex super-henge (Current Archaeology 2007, 17–21). Subsequent comments explain that only a small percentage of a much larger site has been examined and the total number of buildings at the site has been estimated to be several hundred (Parker Pearson et al. Reference Parker Pearson, Pollard, Richards, Thomas, Tilley and Welham2006; Reference Parker Pearson2007; Pitts Reference Pitts2008, 15–16). Whatever the actual situation is regarding the size of this settlement it is hard to imagine that it could ever be untangled from the intensely ritualised landscape in which it is sited, and it seems unlikely that it resulted from permanent village-like occupation. Of particular relevance is the excavator's interpretation that the site was only occupied during the winter because of the absence of carbonised grain or quern stones, the lack of bones from neonatal pigs and cattle, and the evidence for culling of pigs in the mid-winter period (Parker Pearson et al. Reference Parker Pearson, Pollard, Richards, Thomas, Tilley and Welham2006, 9).

A small number of Irish sites have a similar association between large numbers of buildings and large ritual complexes. Eighteen rather small buildings, possibly tent-like structures, of Late Neolithic date were discovered in the immediate vicinity of the passage tomb at Newgrange, Co. Meath, but similar discoveries outside the passage tomb at Knowth are considered to be open air settings used during ceremonies (Grogan Reference Grogan1996, 44–9; Jones Reference Jones2007, 190–1). At any rate the structures are so small they are unlikely to have been suitable for prolonged occupation. A row of approximately 20 somewhat larger huts are located around the south-west of Knocknarea, Co. Sligo, at some remove from the passage tomb cemetery towards the central summit. Seasonal occupation at the start of the Late Neolithic has been suggested for the Knocknarea huts, on the basis of large numbers of concave scrapers found during excavation, although it is not clear why such artefacts should directly indicate seasonality (Bergh 2002, 147–8). The buildings are associated with a series of very substantial banks and ditches that demarcate the eastern side of the hill's summit and the site as a whole is not well understood.

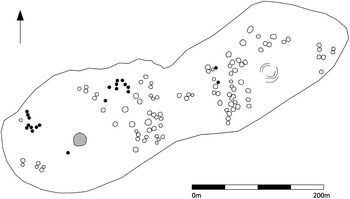

At Mullaghfarna, Co. Sligo (Fig. 1), up to 150 circular foundations ranging between 6 m and 18 m in diameter have been recorded, crowded together on a limestone promontory to the north-east of the Carrowkeel passage tomb cemetery (Grogan Reference Grogan1996, fig. 4.11; S. Bergh pers. comm.). Whilst a number of the foundations are clearly unroofed enclosures, a large percentage of the foundations do appear to represent circular buildings dating from the Middle Neolithic period. Large quantities of concave scrapers have been recovered from excavations at the site, an assemblage similar to that from the huts at Knocknarea, and again Bergh has suggested that this indicates seasonal occupation. A similar site is found on the summit of Turlough Hill, Co. Clare (Fig. 2), where a dense ring of over 100 circular buildings is located surrounding an impressively sized cairn and a newly discovered multiple banked enclosure (S. Bergh pers. comm.). Further to the east there is a large enclosure defined by a stone wall that might possibly be a variant on the causewayed enclosure site type (Grogan Reference Grogan2005a, 125–7). Unfortunately, the different elements on Turlough Hill are not yet dated and the various elements have alternatively been ascribed to the Neolithic or the Bronze Age. Neither of these large settlements has been put forward as a village type settlement, with investigators highlighting the exposed locations as being unsuitable for year round occupation and suggesting they may have only been occupied at certain parts of the year when the nearby ceremonial complexes were the focus of activities (Grogan Reference Grogan1996, 54; 2005a, 119; S. Bergh pers. comm.). However Mullaghfarna, at 220 m, and Turlough Hill, at 275 m, do not constitute high altitude sites in absolute terms and more direct evidence of seasonal occupation must be sought before these sites are discounted.

Fig. 1 Mullagfarna, Co. Sligo: (left) general plan of the building foundations and enclosures and (right) detailed plan of enclosures, Circle 1, and probable houses, Circles 2 & 3 (Grogan Reference Grogan1996, fig. 4.11)

Fig. 2 The western summit of Turlough Hill Co. Clare. The well defined buildings are shown as outlines and the poorly defined buildings as black circles. The cairn is shown in grey towards the south-west, and the multivallate enclosure in grey towards the north-east (after Bergh Reference Bergh2008; Hennessy Reference Hennessey2008)

A Late Neolithic settlement at Barnhouse on Orkney is also located amongst a dense complex of ceremonial sites. Unusually this site has been confidently identified as a village, the excavation report even containing a chapter entitled The Villagers of Barnhouse (Jones & Richards Reference Jones and Richards2005a). Thirteen structures were found within the excavated area, of which perhaps eleven could have been in use simultaneously (Fig. 3). The monumentally constructed House 2 is thought to have served a communal, probably religious purpose, whilst the even larger House 8 is thought to post-date the abandonment of the settlement and also to have been a religious building. It has been suggested that the settlement was organised around two concentric rings and that only half of it lies within the excavated area (Jones & Richards Reference Jones and Richards2005b, fig. 3.31). If this is correct then the total number of buildings would probably lie in the mid-20 s. How the interpretation of the Barnhouse village will be altered by the ongoing excavations of a ‘temple complex’ on the adjacent Ness of Brodgar remains to be seen (Card Reference Card2010).

Fig. 3 The extent of the excavated areas at Barnhouse, Orkney. The suggested organisation of the settlement into two concentric circles is shown (Richards Reference Richards2005)

As mentioned above, the Late Neolithic settlement at Skara Brae has long been identified as a village (Childe Reference Childe1931; Clarke Reference Clarke1976). The term has also been applied to several other large settlement sites on Orkney including those at Pool, Rhinyo, and Links of Notland. A settlement of ‘massive proportions’ is suspected at Bay of Stove on Sandy (Jones & Richards Reference Jones and Richards2005b, 30–4). The full extent of these settlements will only become clear when further fieldwork, in particular large scale excavation, has been undertaken (Barclay Reference Barclay1996, 66–70). Finds assemblages from the limited work already conducted at these sites are impressively large, with both Pool and Links of Notland having produced over 10,000 sherds of pottery to date (Cowie & MacSween Reference Cowie and MacSween1999, 49–50; Sheridan Reference Sheridan1999). Skara Brae itself has been extensively excavated, but it is thought that only eight buildings could have been used simultaneously and some of those may have had ancillary functions. It is quite possibly that the number of households living at Skara Brae was too small for it to be correctly identified as a village. It seems possible that additional buildings were lost to coastal erosion which may mean the original total was higher, a proposition that is rather important if the site is to retain its designation as a village (Garnham Reference Garnham2004, 48–9).

Returning to hilltop locations, there are a number of intriguing fortified hilltop settlements in the south-west of Britain which appear to belong to the mid-4th millennium bc. In Cornwall medium scale excavation has taken place at Carn Brea (Fig. 4), where approximately 10% of the interior was examined. A vast Early to Middle Neolithic artefact assemblage, representing at least 550 vessels and over 26,000 struck lithic pieces, including 2107 implements, was recovered (Mercer Reference Mercer2001, 43). A second Cornish site, Helman Tor, was subject to very small scale excavation and whilst no building plans were recovered, the density of artefacts was surprisingly high. A third Cornish example is suspected at Carn Galver where although small scale excavation in 2009 failed to provide any datable material it did establish the presence of the enclosure (Jones Reference Jones2009). Davies has listed 12 other sites in Cornwall that may fall into this group (2010, 217–30). The earliest activity at Crickley Hill in Gloucestershire is thought to represent a very similar settlement, and it has been suggested that Clegyr Boia in Pembrokeshire, which has been subject to small scale excavation, may also be part of this group of settlements (Vyner Reference Vyner2001, 84). Vyner also suggests that two promontory forts in Pembrokeshire, Clawdd y Milwyr and Castle Coch, may be a coastal equivalent of this style of hilltop enclosure (ibid., 85). The scale of occupation at these sites is as yet unclear but Darvill suggests that between five and ten buildings were located on the hilltops at Carn Brea and Crickley Hill (1996, 81). Mercer has stressed the lack of ‘carefully placed deposits of a ceremonial nature’ deposition at Carn Brea and that the site was ‘extensively used for settlement by a large social group, however intermittently’ (2001, 44).

Fig. 4 Plan of Carn Brea, Cornwall (Mercer Reference Mercer2001, fig. 3.1)

A different type of enclosed hilltop settlement was partially excavated at Thornhill, Co. Londonderry, where several sequentially replaced palisades encircled the summit of a prominent hill overlooking the River Foyle. Although only a small portion of the site was excavated, five possible houses were identified within the excavated area and, if a similar distribution continued across the rest of the enclosed area, quite a large settlement must be envisaged. The large finds assemblage seems to indicate a prolonged period of occupation from the Early to the Middle Neolithic (Logue Reference Logue2003).

Finally, a Beaker period settlement was found on Ross Island, Co. Kerry, adjacent to the well known early copper mine. Excavations revealed ten or 11 hut foundations, 13 concentrations of stake-holes belonging to arrangements of ‘unknown’ type, and plentiful evidence of contemporary metal working activities (O'Brien Reference O'Brien2004, 170–303). Occupation at the site began between 2400–2200 bc and perhaps lasted for several hundred years, but it is suspected these structures belong to a single phase within the overall site chronology. O'Brien is careful to call the settlement a work camp, and goes on to stress the transient nature of mining communities (ibid., 303, 475–7). However there was no direct evidence of seasonality and it remains a possibility that this site may be an early mining village.

Bronze Age Villages: The Definite and the Dubious

Our understanding of Bronze Age settlement in England, Scotland, and Ireland is considerably more developed than for the preceding periods, and there is a dramatic increase in the number of known settlements from most regions. The Early Bronze Age remains somewhat difficult, as the major expansion in settlement really begins during the Middle Bronze Age (Halsted Reference Halsted2007, 167–8). In England and Scotland this expansion continues through the Late Bronze Age and on into the Iron Age. In Ireland there is a different trajectory and the number of known settlements falls away once more in the Late Bronze Age. Settlement sites are exceedingly rare in the Iron Age. Throughout the Bronze Age the isolated farm and the very small hamlet remain the dominant types of settlement but larger sites are known from some regions. Useful summaries of the settlement patterns in different regions are readily available, including Cunliffe's review of southern England, Barnatt's account of settlement in the Peak District, and Feachem's summary of the situation in northern England and mainland Scotland (Cunliffe Reference Cunliffe2004, 33–64; Barnatt Reference Barnatt1987; Feachem Reference Feachem1973). Bronze Age settlement on the Scottish islands has been reviewed by Downes and Lamb and by Armit (Downes & Lamb Reference Downes and Lamb2000, 117–28; Armit Reference Armit1996, 87–108).

In southern and south-eastern England Middle Bronze Age sites such as Itford Hill and Black Patch in Sussex, and Thorny Down, Wiltshire, were originally considered to be small villages, but later analysis suggested that the chronological depth of the sites had been missed, and that in each case only a handful of the buildings were occupied simultaneously (Burstow & Holleyman Reference Burstow and Holleyman1957; Drewett Reference Drewett1982; Ellison Reference Ellison1987, 391; Russell Reference Russell1996, 35–7; Stone Reference Stone1941, 117). Brück's in-depth analysis of Middle Bronze Age settlements in southern England concluded that: ‘most were occupied by a single household, perhaps comprising a nuclear or small extended family group’ (Brück Reference Brück1999, 145–7). Similarly the early phase at Jarlshof, referred to as a ‘Late Bronze Age village’ by Hamilton, appears to have been a rather small Late Bronze Age settlement consisting of just a few houses and is hardly large enough to constitute an actual village (Hamilton Reference Hamilton1956, 202). The row of three ‘terraced’ houses at Cladh Hallan on South Uist, occupied continuously between 1100 and 400 bc, has also been referred to as a village (Parker Pearson et al. Reference Parker Pearson, Sharples and Symonds2004, 62–70). The settlement continues to the south of the excavated area, but there would have to be a very substantial extension waiting to be discovered under the sand dunes to warrant the use of the term village.

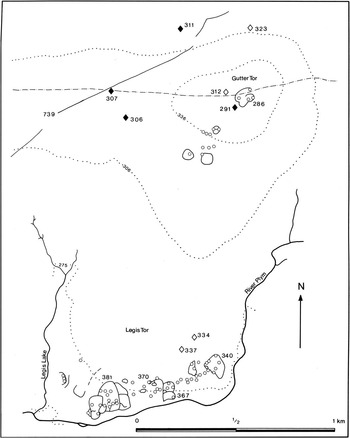

A different picture exists in south-west England where extensive survey work and limited excavation has taken place. Simmons divides Bronze Age settlements in Devon into three groups; enclosed hut settlements, huts with fields, and hut villages. Of the latter group, some sites are very compelling examples of possible villages, such as Rider's Rings and Stanton Down on Dartmoor, which consist of 23 and 68 circular buildings respectively, and Cunliffe has continued to refer to these sites as villages (2004, 53–6; Simmons Reference Simmons1970). As part of the Shaugh Moor project, the Plym Valley was extensively surveyed and a large number of settlements were recorded, believed to date from the Middle and Late Bronze Age (Balaam et al. Reference Balaam, Smith and Wainwright1982). The settlements occur in a variety of shapes and sizes but during that survey they were simply divided into two groups, enclosed and unenclosed. The presence of possible villages was not discussed directly, despite the very large number of buildings present at some of the sites. At Legis Tor (Fig. 5) and Whittenknowles Rocks for example, each site consists of around 50 buildings many of which are thought to have been occupied simultaneously (Balaam et al. Reference Balaam, Smith and Wainwright1982, fig. 17, 241–8). It was suggested that transhumant farming was practised in the area, with animals being brought both up to the high ground in the summer and down onto the valley floor in the winter, but that the majority of settlements, located on the middle slopes, were permanently occupied. Sadly a lack of large scale excavation at these sites means in most cases our knowledge of them has developed little since they were discussed by Worth (Reference Worth1943).

Fig. 5 Legis Tor, Dartmoor, Devon. (Balaam et al. Reference Balaam, Smith and Wainwright1982, fig. 20)

The situation in Wales is quite different as Bronze Age settlement is very scarce. A survey of over 750 Welsh round-houses, from 189 different sites belonging to all periods, found only a very small number could be identified as belonging to the Bronze Age. This study highlights the point that it is only in the Late Bronze Age–Iron Age transition that round-houses become a common feature in the archaeological record. None of the securely dated Bronze Age buildings occurs in a village-like settlement (Ghey et al. Reference Ghey, Edwards, Johnston and Pope2007, 1.3, 4.1).

In Ireland a total of 583 structures have been excavated, dating from the Beaker period to the Late Bronze Age, at 260 different locations. Taking into account chronological considerations, it appears that the vast majority of these sites consist of single buildings whilst a small number consist of groups of 2–6 contemporary buildings (Ó Néil Reference Ó'Néil2009, 35). Few Irish sites have ever been described as being villages and this perhaps reflects the perceived absence of villages from the modern landscape influencing archaeological terminology. Given this long standing avoidance of the term ‘village’ it is surprising that a small Early Bronze Age settlement excavated at Ballybrowney, Co. Cork has recently been described explicitly as a village (Cotter Reference Cotter2005, 42). The settlement consisted of three adjacent enclosures, only one of which definitely contained a structure, and three unenclosed round-houses in a tight cluster. Whilst elements of the settlement clearly extended beyond the excavated area in two directions, unless substantially more buildings were to be discovered it would be hard to accept the excavators’ preliminary conclusion that the settlement represents a village and it will be interesting to see if the term is retained when the site is fully published.

Between October 2002 and August 2003 an exceptionally large Middle Bronze Age settlement was excavated at Corrstown, Co. Londonderry (Conway et al. Reference Conway, Gahn and Rathbone2004; Ginn & Rathbone Reference Ginn and Rathbone2012). The settlement (Fig. 6) consisted of over 70 round-houses generally grouped into pairs or small rows that were linked by narrow cobbled paths running from doorway to doorway. Many of the individual buildings showed clear evidence of having been rebuilt on repeated occasions. A 10 m wide cobbled road surface ran through the settlement and the small paths were, in some instances, seen to connect the houses with the road surface. Most of the buildings were of a similar ‘segmented ditch’ style but a small number of buildings with a quite different ‘slot trench’ design were positioned around the perimeter, suggesting functional differences. A single house near the centre was enclosed by a substantial ditch, but the building itself was of the ‘segmented ditch’ type and otherwise unremarkable (Ginn & Rathbone Reference Ginn and Rathbone2012, 202–17, 234). A suite of radiocarbon dates from across the site were very tightly grouped and indicated that the settlement's main occupation phase was between 1370 and 1250 cal bc (McSparron Reference McSparron2012, 287). At the settlements fullest extent at least 60, perhaps even 70, of the buildings may have been occupied simultaneously. The finds assemblage from the site consisted of huge quantities of crude, bi-polar reduced flints and plain functional pottery and it could be legitimately described as being vast, mundane, and monotonous. High status or unusual artefacts, such as polished stone objects, were present only in very small quantities and no metal artefacts were recovered, although several stone moulds were. This assemblage provides an interesting comparison to the Neolithic assemblages from County Sligo described above which were also large and homogeneous. The size and complexity of the Corrstown settlement indicates that it can confidently be classified as a village, and the benefits of such large scale excavation are clear. Unfortunately the area around the Corrstown village was heavily developed during the 19th and 20th centuries and little is known about its contemporary surroundings (Ginn & Rathbone Reference Ginn and Rathbone2012, fig. 1.5).

Fig. 6 Corrstown, Co. Londonderry: simplified post-excavation site plan (Ginn & Rathbone 2012, illus. 1.4)

A second large Middle Bronze Age settlement that was subject to total excavation in advance of development was found at Area 3000/3100 Reading Business Park, Berkshire (Moore & Jennings Reference Moore and Jennings1992; Brossler et al. Reference Brossler, Early and Allen2004). This site consisted of a dense circular cluster of round-houses (Fig. 7) of which, the excavators argued, up to 14 may have stood simultaneously (Brossler et al. Reference Brossler, Early and Allen2004, 122). The houses appear to be grouped into pairs and a linear space devoid of archaeological features, around 10 m in width, was interpreted as being a road running through the settlement (ibid., fig. 3.7). The size of this site places it at that hazy boundary between the large hamlet and the small village. If the 14 paired round-houses represent just seven households, as the excavators suggested, then a designation as a hamlet rather than a village may be more valid.

Fig. 7 Reading Business Park, Areas 3100 and 3000B, Berkshire (Brossler et al. Reference Brossler, Early and Allen2004, fig. 3.7)

A third relevant site has recently come to light at Ronaldsway Airport on the Isle of Man. Taking into account re-interpreted evidence from the 1930s excavations, newly excavated buildings, and other structures identified through geophysics, the excavators have concluded that the settlement was a village continually occupied by 10–20 households from around 1500 to 800 cal bc (British Archaeology 2008, 7). Further details about this site are eagerly awaited.

The three large settlements described above are all from lowland contexts, although technically Corrsown and Ronaldsway lie within the traditional designation of the highland zone. Within the uplands of Britain, surveys have revealed large numbers of prehistoric settlements, often associated with impressively large field systems. Unfortunately only a small number of sites have been subjected to large scale excavation.

The linear arrangement of nine house platforms on Green Knowle, in the Scottish Borders, is possibly a little too small to be classed as a village, but the group of 18 house platforms on the other side of the valley at White Meldon appears to be a reasonable candidate (Feachem Reference Feachem1961; Jobey Reference Jobey1980). Excavation at Green Knowle indicated occupation in the mid-2nd millennium BC and that the occupation lasted for some time. Jobey speculated that Green Knowle had a population of between 40 and 50 people, which may be large enough to merit the site's consideration as a village or, certainly, a large hamlet; the implication would be that the population at White Meldon would have been perhaps twice this figure (Jobey Reference Jobey1980, 94).

At Lintshie Gutter, Perthshire, the total number of building platforms is impressively high at 32. Eight of the platforms have been excavated and dates were obtained spanning the very Early Bronze Age to the late Middle Bronze Age although, in most instances, there was evidence of successive buildings on each platform. Not all of the excavated platforms were found to contain houses; on Platform 5 the circular building contained an oven and was identified as a possible cook house, whilst the later structures on Platforms 1 and 7 do not appear to have been dwellings (Terry Reference Terry1995, 423–4). It was concluded that, whilst not all of the platforms were necessarily occupied simultaneously, the settlement would have had a sizeable population over a prolonged period (ibid., 423). The suggestion that the settlement began as a dense cluster of houses at the eastern edge and subsequently expanded in a more disperse linear arrangement westwards along the slope is certainly reminiscent of the manner in which some villages of recent periods are known to have developed (Roberts Reference Roberts1996, fig. 5.6).

Finally, Knock Dhu in Co. Antrim is an interesting site where recent investigations by Queens University Belfast have started to provide a much clearer idea of the range and date of activity (Macdonald Reference Macdonald2008). Knock Dhu is an inland promontory fort located on the east facing scarp of the Antrim plateau. Steep slopes and cliffs protect the north, south, and east, and the gentle western slope is blocked by a triple rampart, effectively providing an enclosed area of c. 8 ha. Radiocarbon dates taken from a variety of contexts from the ramparts and accompanying ditches indicate construction in the Late Bronze Age with alterations continuing well into the Iron Age. Within the enclosed area numerous house platforms are present, with a distinct concentration close to the ramparts. A minimum of nine circular buildings are present, but a total of 25–30 has been suggested. Five structures have been subject to partial excavation, and whilst artefacts were noticeably scarce, radiocarbon dates indicated that the buildings were occupied in the Late Bronze Age (Ó Néil Reference Ó'Néil2009, 61–3). Similar sites, including Haugheys Fort in Co. Armagh, Mooghaun in Co. Clare, and Rahally in Co. Galway, have been subject to large scale excavation but did not provide evidence for sizeable settled populations (Lynn Reference Lynn2003, 65–70; Grogan Reference Grogan2005b, 241–5; O’ Sullivan Reference O’Sullivan2007, 89). This suggests that, despite a generally similar appearance, these sites may have been used in a wide variety of ways and that the role of each will have to be established on an individual basis.

The Village as a Settlement Form

Reviewing the range of sites that have been previously identified as villages reveals an unconscious assumption on the part of some authors that prehistoric villages were significantly smaller than Saxon or medieval ones, but this notion does not stand up to detailed scrutiny. Perhaps the ultimate expression of this reduced standard can be seen in Schillibeer's (1829) plan of Grimspound in Devon, where the stone built enclosure containing 24 rather small huts is identified as a ‘Town’ of the Ancient Britons (Patterson & Fletcher Reference Patterson and Fletcher1996, fig. 3). The concept of the prehistoric ‘small village’ is here rejected as being identical to that of the hamlet. It is suggested that in future discussions no settlement be labelled as a village until it has been definitively shown to have been the residence of more than a small number of households. On the other hand, it would seem that there are instances where other authors have consciously avoided using the term ‘village’ to refer to large settlements when this is likely to be the most appropriate designation.

It appears that in both the Neolithic and Bronze Ages small villages are very rare and large villages are exceptionally rare. Large hamlets are considerably more common but small hamlets and isolated farmsteads remain the norm for most areas. Two sites from the Late Neolithic in Orkney, Skara Brae and Barnhouse, may well represent villages, assuming in both cases that the original extents of the settlement exceeded the remains recorded to date. Other Orcadian sites that have been less extensively examined may also represent villages, but new fieldwork is needed at those sites. It also seems that the fortified hilltop settlements in the south-west of Britain might represent large hamlets and small villages, and these sites urgently need to be investigated in more detail. The large settlement at Durrington Walls is clearly of a size that the term ‘village’ could happily be applied to it, but given its location and probable seasonal occupation it may not be appropriate to consider it as a village. The much larger settlement at Mullaghfarna, Co. Sligo, may represent a large Neolithic village, but until further excavations have taken place at this site many questions will remain about how it should be categorised. The same comments apply to Turlough Hill in Co. Clare, with the additional need for the site to be conclusively dated; in 2012 a team from Galway University commenced a programme of excavation at the site and the results they produce over the next few years will be of great interest. The palisaded enclosure at Thorn Hill, Co. Londonderry, seems another reasonable example of a village-like settlement, providing the distribution of houses continues into the unexcavated areas, whilst the status of the settlement on Knocknerea, Co. Sligo, is rather less clear.

From the Bronze Age there are many more potential villages and only a selection of them have been detailed here. The Corrstown village, Co. Londonderry, is the clearest example, because of its large size and the fact that it was subject to total excavation. The other satisfying examples of Bronze Age villages are Reading Business Park Area 3000/3100, Berkshire, Ronaldsway Airport, Isle of Man, and the larger settlements on Dartmoor and in the Scottish borders. Additionally it is clear that there are quite a number of sites in the uplands of Britain that consist of large numbers of circular house foundations that, to date, have only been subject to field survey or very limited excavation. Large scale investigation at these sites should establish the internal chronology of those settlements and might add considerably to the recognised number of village sized settlements.

The Variety of Life

A striking aspect of the sites reviewed above is the sheer amount of variability that is demonstrated. During the Early Neolithic small hilltop settlements in south-western Britain seem to take advantage of naturally defensible positions and enhance them with often substantial banks and ditches, whilst a palisaded hilltop enclosure at Thorn Hill, Co. Londonderry, contained numerous small buildings and was occupied for a long duration. In the Late Neolithic medium sized unenclosed settlements occupy low lying positions in Orkney, and a medium sized settlement is found in a dramatic upland location at Knocknerea in Co. Sligo, associated with an extensive system of banks. A potentially massive settlement has been identified within the heavily ritualised landscape at Durrington Walls, Wiltshire, and a similarly extensive settlement at Mullaghfarna in Sligo is also located within a highly monumentalised area. The forthcoming results of the excavations at Turlough Hill, Co. Clare, may add a third site to this group.

Similar diversity in size and form is seen in the Middle and Late Bronze Age. Numerous medium and large scale settlements seem to be present on Dartmoor, occurring in both enclosed and unenclosed forms. Medium sized unenclosed sites have been examined in upland locations in Scotland and in lowland locations at Reading Business Park in southern England and Ronaldsway on the Isle of Man. The settlement at Corrstown is exceptional both in terms of the scale of the settlement and the extent of the excavations, but it should be pointed out that there was no indication of its presence prior to the beginning of test excavations at this site in 2001, and it is therefore at least possible that other similarly sized sites await discovery (Ginn & Rathbone Reference Ginn and Rathbone2012, 3). The potential for more of the numerous upland settlements to eventually be identified as villages is high.

Tough on Villages, Tough on the Causes of Villages!

The development of villages is often seen as an important stage in a linear progression towards ever more complex social forms. Malone has described a progression in Britain and Ireland during the Neolithic in terms of an evolution from initial mobile family bands, through loose tribal groups, and into chiefdoms during the Late Neolithic, who were able to exert considerable political control. This is linked to the rise of larger and more complex forms of settlement and religious site and it is suggested such processes can be reversed under the influence of external factors such as climate change (Malone Reference Malone2001, 204–6). A major study of Bronze Age settlements in northern and central Europe regards settlements as far apart as southern Scandinavia and Sicily as being influenced by a large scale trend towards nucleation caused by the rise of chieftains, in some places simultaneously with the rise of a ‘ritual elite’. The rise of these new elites is seen to be supported by changes in agricultural management and increasing levels of control exerted over the flow of commodities along steadily expanding trade networks (Earle & Kristiansen Reference Earle and Kristiansen2010a, fig. 1.6; Reference Earle and Kristiansen2010b, 243–9). Cunliffe meanwhile sees the development of trade networks with an origin in the Aegean as the ultimate fuel behind the rise of elites across Atlantic Europe, and that these newly arisen elites attempted to control all aspects of society (Cuniffe 2001, 213–17). Fredengren has expressed concerns that narratives of these types are inherently based on modern capitalist principles and overlook other processes that may have been influential within a society (Reference Fredengren2002, 3–13). Whilst this ‘proto-capitalist’ model might be applicable for parts of mainland Europe it is far less convincing for Britain and Ireland. For the Neolithic and Bronze Ages in these regions settlement nucleation is perhaps better regarded as a result of local innovations, experiments that developed and concluded without either becoming permanent features of settlement pattern or spreading widely beyond their initial territories.

A Response to Intensification of Agriculture?

The motivating factors suggested to apply to much of Europe appear to have been present in Britain and Ireland without leading to the widespread development of villages. For example, large field systems can be seen to mark an intensification of agricultural practices, but where Neolithic examples occur in North Mayo and the Burren they are not associated with larger settlements (Caulfield et al. Reference Caulfield, Warren, Rathbone, McIlreavy and Walsh2009a; Jones Reference Jones2003, 188). Conversely where larger Neolithic settlements have been identified they have not yet been connected to large field systems. The large pig bone assemblage reported from Durrington Walls reflects some form of intensified agriculture but, with the exception of this site, settlement in the region is generally thought to have been highly mobile and small in scale (Pollard & Reynolds Reference Pollard and Reynolds2002, 122–4). It is hard to see why nucleation would only occur in one location if there was a general increase in the productivity of agriculture, if nucleation is seen to be directly linked to such developments in farming regimes.

During the Middle Bronze Age large field systems develop on Dartmoor where they are associated with settlements of different sizes, including the larger village sized examples. However such field systems develop simultaneously all along the upper and middle Thames Valley where Reading Business Park is the only known large settlement, and in Cambridgeshire, where no large settlements are currently known (Brossler et al. Reference Brossler, Early and Allen2004, fig. 3.1; Flemming Reference Flemming1996, fig. 1; Malim Reference Malim2001; Yates Reference Yates2001). The massive burnt stone mound found immediately north-east of the settlement at Reading Business Park may indicate communal food preparation on a very large scale, and the groups of four-post structures indicate well organised management of supplies. However both features seem to represent a simple up-scaling of contemporary practices occurring at smaller settlements in the area and are best seen as an effect of nucleation, rather than a cause.

A Response to the Development of Trade Networks?

There is convincing evidence of increasingly expansive trade routes developing in Britain and Ireland throughout the Neolithic and Bronze Ages but, again, it is difficult to see a direct link to the development of larger settlement forms. Few of the sites discussed here show any evidence of exotic imported artefacts and when they do occur they do so in the sorts of small quantities seen at more typically sized settlements. For example, long distance trade at Thorn Hill was only represented by a single fragment of a Langdale axe whilst more local trade was represented by several porcellanite axes and a large flint assemblage (Logue Reference Logue2003, 154–5). At Barnhouse the large assemblage of Grooved Ware (c. 6000 sherds) and lithic material (c. 1585 pieces) are directly linked to production occurring within and immediately outside the settlement (Jones & Richards Reference Jones and Richards2005b, 34–43). The only artefacts that were unquestionably an import from outside the immediate area were 23 pieces of Arran pitchstone, a source c. 480 km away, but detailed analysis suggests that this material was not accorded any special treatment. A similar local focus has been suggested for Skara Brae and the other Late Neolithic settlements on Orkney (Middleton Reference Middleton2005, 294–5). The far south-west of Ireland is known to have been involved in an international copper trade, but no exotic artefacts were found at the settlement at Ross Island and settlements in this area are not known to have moved towards nucleation during the Bronze Age (Cunliffe Reference Cunliffe2001, 225). The settlement at Corrstown, despite being located on the coast and in a region where metalwork was being traded with southern England, produced no artefacts that could not have been sourced from the local area (Ginn & Rathbone Reference Ginn and Rathbone2012, 156; Waddell Reference Waddell1998 figs 82, 94, & 132). Long distance trade was only conclusively demonstrated at Reading Business Park by a single fragment of a shale bracelet most likely derived from Dorset whilst, at Lintshie Gutter, it was only represented by three beads, one of amber and two of jet (Brossler et al. 2004, 98–9; Jobey Reference Jobey1980, 93).

An exception to this pattern of low levels of imported material is found in the Early Neolithic enclosures in Cornwall. Large amounts of pottery from the Lizard peninsula was brought 27 km to Carn Brea, whilst local sources of clay were ignored. It is estimated that 50% of the lithic assemblage was also imported, with East Devon being suggested as the likely source (Mercer Reference Mercer2003, 60). Similar pottery had been transported some 65 km to Helman Tor although, at that site, local pottery accounted for approximately 76% of the assemblage. In contrast, imported material made up 77% of the lithic assemblage (ibid., 64). It seems that both these sites were able to acquire material from a large area of the south-western peninsula. Davies has suggested that the Early Neolithic enclosure settlements in Cornwall were located in order to control route ways, and has sought to place the enclosures in the context of trade routes around the Irish Sea – but this idea is somewhat undermined by the lack of exotic material from the three excavated sites (Davies Reference Davies2010, 196–9, 210).

A Response to the Development of Hierarchical Societies?

Although there is some internal variability within some of the Neolithic sites, it would be difficult to argue for the presence of internal social stratification based on the available evidence from the settlements. Plans so far recovered from the hilltop enclosures in the south-west are not complete enough to allow the identification of such internal differences in status. The locations themselves may be more revealing as it has been claimed in other contexts that dramatic hilltops are chosen to emphasise the status of the occupants, and the creation of large banks around settlements is often seen as a statement regarding the power of the occupants (Brown Reference Brown2009, 193–5).

The two largely excavated Late Neolithic sites on Orkney each contain examples of noticeably larger buildings, but these do not seem to have been elite residences. House 2 at Barnhouse is a larger building than the others in the settlement but it is argued that it was a communally used religious building and there is little to indicate the presence of a professional ‘ritual elite’. A similarly differentiated building at Skara Brae, House 8, is thought to have been used for communal ‘industrial’ activities (Malone Reference Malone2001, 60). A small percentage of the buildings at Mullaghfarna are associated with large enclosures while the majority are not, but what these enclosures were used for is quite unclear. It is possible that these denote some difference in the status of the occupants of the adjacent buildings, but this cannot be assessed properly whilst their function remains unknown (Grogan Reference Grogan1996, 54).

The Bronze Age is often described as seeing the rise of chieftains and a more hierarchical society. Examples of this include the change to individual burial rites during the Early Bronze Age, and the deposition of metal hoards during the Late Bronze Age, both activities interpreted as reflecting the wealth and influence of particular individuals (Cunliffe Reference Cunliffe2001, 247–51; Cooney & Grogan Reference Cooney and Grogan1994, 164–7). These changes are not readily apparent in the settlement archaeology and the ‘chieftains house’ has remained quite elusive. Areas such as the Plym valley, which contain settlements of all size in close proximity to each other, provide a particular challenge for those attempting to link social hierarchies with settlement form. The development of hillforts in some regions during the Late Bronze Age is one area where social hierarchies may be more clearly reflected in settlement archaeology. The idea that the hillforts in North Munster were positioned to control route ways is very intriguing, as settlement form may be being influenced by both the rise of social hierarchies and by the development of trade routes (Grogan Reference Grogan2005a, 121–5).

Structure 19 at Corrstown was defined by a large horseshoe shaped ditch, but the building itself and the associated artefacts were not especially remarkable. It was argued that the handful of larger buildings within the settlement were the result of multiple rebuilding phases on the same location rather than reflecting the use of more inherently complex architecture (Ginn & Rathbone Reference Ginn and Rathbone2012, 220–2). The surfacing of the roadway is indicative of a large piece of civil engineering that may have involved most, if not all, of the population, but it seems to have been used by much of the settlement and, again, perhaps is better interpreted as a communal endeavour rather than something organised for the aggrandisement of an elite class. At Reading Business Park the buildings do not display any signs of differential status but there is evidence of collective organisation in the form of the massive burnt stone mound and areas set aside for four-post structures. At Lintshie Gutter the presence of buildings that housed ovens may hint at some level of craft specialisation, and no other site provides such clear evidence of buildings with such specific and particular purposes. However, there is no particular reason to suggest that this was not communally organised and the activity is hardly of a large enough scale to suggest occupational specialisation.

Finally it is worth noting that three Late Bronze Age sites found on the Thames Valley are particularly revealing when considering the factors which lead to settlement nucleation. Located next to the river, Runnymede Bridge, Marshall's Hill, and Wallingford, have all been identified as high status sites, that are connected directly with trade, and which are located in areas of particularly marked agricultural intensification (Yates Reference Yates1999, 160). However, despite the presence of the three suggested causes of nucleation at these sites, it seems that they have not taken the form of villages and that only at specific occasions would large congregations of people assemble at these sites.

A Parthian Shot

This paper has probably raised far more questions than it has answered, and many of the individual points addressed here could be usefully explored in much greater detail. It is hoped it has usefully highlighted several long standing issues in the terminology used to describe prehistoric settlements. More importantly it is hoped that a previously overlooked and very curious aspect of the settlement archaeology of both the Neolithic and Bronze Ages has been brought into sharper focus. The presence of sporadic outbreaks of settlement nucleation challenges widely held notions of the factors which led to the development of villages. It seems likely that regionally and chronologically specific explanations for these developments will need to be established through linking information about local environment and farming regimes to refined chronologies of different sizes of settlement within a specific area.

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the presence of these small villages has been deliberately overlooked in this paper. As work progresses on this subject it should be possible to examine how these villages affected the daily experiences of those who lived within them, and how their presence affected those who lived without. As Roberts has highlighted, permanently occupied villages create ‘tremendous opportunities for increased social interaction, choice of marriage partners, ceremonies and merrymaking’ and plenty more besides (1996, 36). For the occupants of these rare larger settlements our current models may be underestimating the complexities of their lives, and only through detailed examinations of their settlements can this shortcoming be redressed. In many areas new and large scale fieldwork is needed, but these settlement sites are surely some of the most interesting and challenging that any archaeologist could choose to work on.

Acknowledgments

Early drafts of this paper were read by Steven Linnane and by Vicky Ginn who both provided useful comments. A lengthy night in a bar on Achill Island with Stefan Bergh generated many useful ideas and lines of enquiry for which I am particularly indebted. Three anonymous reviewers provided detailed comments that have strongly influenced the final appearance of this paper, and their input was much appreciated. Christina Rathbone assisted greatly with the final edit. All faults, flaws, and failings remain the responsibility of the author alone.