Introduction

Anthrax, a gram-positive rod, is a Category A bioterrorism agent, which can be weaponized for aerosol dispersion.1 Anthrax is a complex infection, with within-host dynamics that may result in delayed germination of spores after an attack, as well as multifactorial environmental, weather, and attack factors that determine the spore density and impact of an attack. Anthrax may present as cutaneous, gastrointestinal, or inhalational disease, leading in many cases to fulminant disease associated with meningitis, coma, and death. Without treatment, the fatality rate for inhalational anthrax is 80%-100%.Reference Toth, Gundlapalli and Schell2 In addition to treatment of ill patients with antibiotics, mitigation of potential exposure requires post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) of a larger number of exposed, well subjects, usually in the face of uncertainty as to the attack size and radius of exposure. The size of the estimated area of contamination, and the people present within that area, determine the requirements for PEP. Secondary aerosolization of spores, for example on the clothes of people initially exposed, may also put individuals (who were not present at the attack site) at risk. The mainstay of PEP is antimicrobials, usually ciprofloxacin or doxycycline, given as soon as possible after exposure and continued for 60 days,Reference Inglesby, O’Toole and Henderson3 a duration selected due to historical data which suggest delayed spore germination for as long as six weeks post-exposure. Vaccines can also be used as PEP, but immunity is acquired after 21 days; hence, the main value of vaccination is protection against late germination of sequestered spores.Reference Friedlander, Grabenstein, Brachman, Plotkin, Orenstein, Offit and Edwards4

The approach of anthrax attack could directly inform the public health response to the attack. There are valuable lessons learned from past events. In 1979, an accidental release of anthrax spores from a Soviet military microbiology facility occurred in the city of Sverdlovsk, Russia resulting in at least 77 cases with 66 deaths.Reference Meselson, Guillemin and Hugh-Jones5 The distribution of cases was restricted to a long, narrow region up to 4km, including three high-risk zones, corresponding to a plume released from the facility and atmospheric dispersion in accordance with meteorological conditions documented at the time.Reference Meselson, Guillemin and Hugh-Jones5 During the Amerithrax mail attack in the United States (US) in 2001, resulting in 22 cases, 32,000 persons required antimicrobial prophylaxis in New Jersey alone.Reference Jernigan, Raghunathan and Bell6 The primary attack in this case, however, was through the mail, not airborne.Reference Bresnitz and DiFerdinando7 The spores (ranging from three to five microns) were dispersed widely in postal facilities through the action of mail sorting machines, from the edges of sealed envelopes.Reference Bresnitz and DiFerdinando7 This resulted in wide-spread contamination and the need for a large-scale response.

Release of even a small amount of aerosolized anthrax in an urban, populated area could expose tens of thousands of people, and overload the public health system. Since conducting anthrax attack experiments is not feasible or ethical, modelling studies are an important tool for decision support and response planning. In the case of anthrax, it is important to avoid over-estimating or under-estimating the extent of contamination, and to consider all factors which could affect the area of contamination. These include wind and weather conditions, the height of a release, whether spores are weaponized with the use of silica, topography, and population density. Dispersion modelling is generally done using three modelling approaches: Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD), Gaussian Plume, or a Lagrangian approach. Each modelling method is useful for different scenarios: CFD models are generally used to model dispersion up to a distance of 1km; Gaussian Plume model can be used to model dispersion up to 100km; and the Lagrangian approach can be used to model dispersion up to 1,000km. Gaussian plume models are the most widely used models, as they require least computational resources; however, due to steady state and straight-line approximations, the results may not be as accurate as Lagrangian or CFD models. A compromise between accuracy and computational requirement is an integrated Lagrangian Gaussian Puff model, such as CALPUFF.

The aim of this study is to systematically review and evaluate the approaches to mathematical modelling of weaponized anthrax attack to support public health decision making and response.

Methods

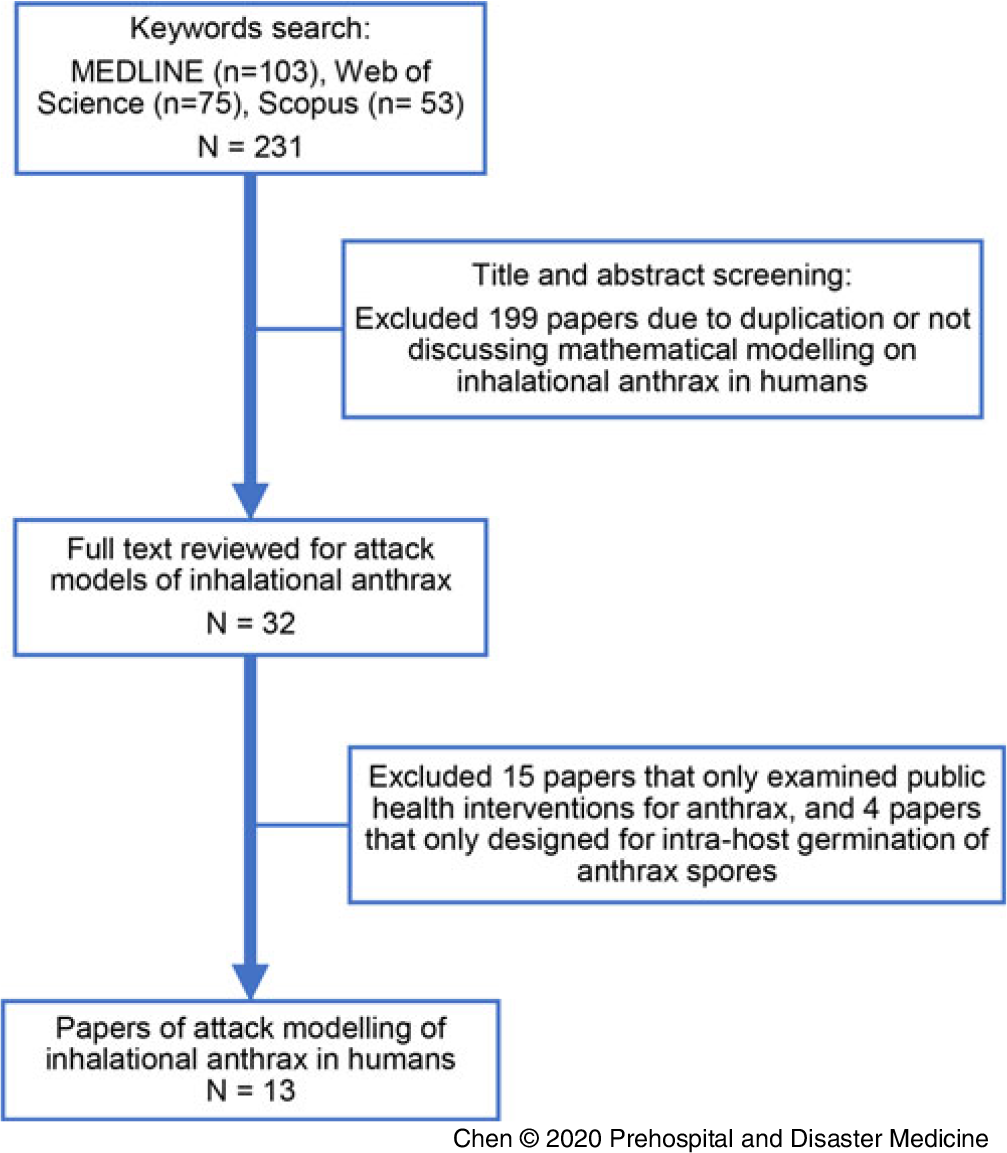

The systematic review of mathematical modeling studies concerning human aerosolized (weaponized) anthrax attacks was conducted using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) criteria.Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman8 Papers were searched from three databases: Medline (US National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health; Bethesda, Maryland USA; 1946 to present), Web of Science (Thomson Reuters; New York, New York USA; 1900 to present), and Scopus (Elsevier; Amsterdam, Netherlands; 1970-present). Search keywords used were: “anthrax,” “bacillus anthracis,” “model,” “modeling,” “modelling,” “strategy,” “inhalational,” “aerosolized,” “atmospheric,” “dispersion,” “plume,” “deliberate release,” “biological attack,” and “bioterrorism.” The search strategy is outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Search Strategy and Selection of Papers.

Inclusion Criteria

The systematic review was focused on studies of mathematical models of human inhalational anthrax attacks. Eligible studies had to fulfil the following criteria: (1) peer-reviewed journal articles, (2) published in English, (3) primary focus on inhalational anthrax in humans, (4) mathematical modelling, and (5) described the geographical dispersion of anthrax spores after an attack.

Exclusion Criteria

The following studies were excluded: (1) non-mathematical modelling studies, (2) laboratory experiments on anthrax, (3) non-human studies, (4) models not designed for inhalational anthrax, and (5) models that only examined public health interventions for anthrax or intra-host germination of anthrax spores.

Review

Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, paper review and selection were conducted by one researcher (XC), reviewed by one researcher (PB), and overseen by investigators (CRM, DH, CD, CdS, and SL). The results from the review are presented in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines.Reference Braithwaite, Fridsma and Roberts9 Each study was reviewed for the following criteria: (1) modelling approach and purpose of model, (2) inclusion of atmospheric dispersion, (3) simulated scenario, (4) model validation using Sverdlovsk (1979) or US (2001) datasets, (5) strengths and limitations, and (6) potential for real-time decision support.

Results

A total of 13 mathematical modelling studies of human inhalational anthrax attacksReference Braithwaite, Fridsma and Roberts9-Reference Wein, Craft and Kaplan21 were identified, and Table 1 shows the type of identified studies. All the selected studies were categorized into two main types: studies that took dispersion of anthrax spores into consideration and used dispersion modelling as part of their model (six papers);Reference Carley, Fridsma and Casman10,Reference Isukapalli, Lioy and Georgopoulos12-Reference Nicogossian, Schintler and Boybeyi14 and studies that did not consider dispersion of anthrax spores (seven papers).Reference Braithwaite, Fridsma and Roberts9,Reference Ho and Duncan11,Reference Nordin, Goodman and Kulldorff15,Reference Rainisch, Meltzer, Shadomy, Bower and Hupert16,Reference Walden and Kaplan18,Reference Wein and Craft20 Three models simulated the outbreak scenario in Sverdlovsk in 1979 or used the Sverdlovsk outbreak data,Reference Nordin, Goodman and Kulldorff15,Reference Rainisch, Meltzer, Shadomy, Bower and Hupert16,Reference Walden and Kaplan18 and four models simulated the US anthrax attack in 2001 or used the data for modelling.Reference Braithwaite, Fridsma and Roberts9,Reference Isukapalli, Lioy and Georgopoulos12,Reference Webb and Blaser19,Reference Wein, Craft and Kaplan21

Table 1. Results of Systematic Review of Attack Models on Human Inhalational Anthrax

There were 13 attack models, which are summarized in Table 2. Only six of them used some form of atmospheric dispersion modelling to estimate the concentration of anthrax spores. LawrenceReference Wein, Craft and Kaplan21 used simple Gaussian Plume to compute number of spores inhaled by a person in the vicinity of anthrax release point. However, their study did not consider change in wind conditions and the effect of terrain, which can influence the dispersion of spores. ReshetinReference Reshetin and Regens22 developed a model based on the NAUA Mod4 computer program, which is used to predict behavior of polydisperse aerosols in a closed vessel, but their model lacks validation. Another well-accepted modelling tool, BioWar,Reference Carley, Fridsma and Casman10 uses a simplistic Gaussian Puff model to estimate anthrax spore dispersion and concentrations. IsukapalliReference Legrand, Egan, Hall, Cauchemez, Leach and Ferguson13 developed the Modelling Environment for Total Risk Studies of Emergency Events (MENTOR-2E) system, which used CALPUFF, a non-steady state integrated Lagrangian Gaussian puff model, to calculate anthrax concentrations in the state of New Jersey. Similarly, LegrandReference Legrand, Egan, Hall, Cauchemez, Leach and Ferguson13 developed a probabilistic model using SCIPUFF, a Lagrangian puff dispersion model using Gaussian Puffs, to estimate anthrax concentration in atmosphere following a point source release. NicogossianReference Nicogossian, Schintler and Boybeyi14 used Operational Multiscale Environment Model with Grid Adaptivity (OMEGA), a CFD model, to estimate the concentration of weapon-grade anthrax spores released in a subway system.

Table 2. Summary of Mathematical Modelling on Human Inhalational Anthrax Attacks in Literature

Abbreviations: CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; ESR, emergency surveillance and response; PEP, post-exposure prophylaxis.

a Using Sverdlovsk-1979 or USA-2001 Datasets.

Of the seven attack models that did not consider atmospheric dispersion of anthrax spores, two models simulated mail-borne transmission of anthrax spores.Reference Ho and Duncan11,Reference Walden and Kaplan18 Webb, et alReference Webb and Blaser19 simulated cross-contaminated postal letters that contained anthrax spores, and described the infections in recipients and matrices of transition probabilities acting on state vectors. Ho, et alReference Ho and Duncan11 simulated the release of 1g or 100mg of anthrax spores from envelopes in a mail room equipped with a ventilation system. Using aerodynamic particle sizers and slit samplers, they showed that due to shuffling, there is an initial jump in aerosol concentration followed by a decay over time. The remaining five models were developed for different purposes: (1) to estimate size and time of bioterror attack using a Bayesian approach;Reference Walden and Kaplan18 (2) to estimate casualties using a combination of disease progression model with the distribution of antibiotics and vaccinations;Reference Wein and Craft20 (3) to evaluate the sensitivity and timeliness of bioterrorism surveillance system using Poisson-based prospective space-time scan statistics;Reference Nordin, Goodman and Kulldorff15 (4) to incorporate widely varying estimates of the probability of attack in an emergency surveillance and response system;Reference Braithwaite, Fridsma and Roberts9 and (5) to predict the epidemic curve and impact of PEP using data as short as three days after attack using a publicly available software Anthrax Assist. Reference Rainisch, Meltzer, Shadomy, Bower and Hupert16

Out of all the modelling studies, only two models appeared to be usable for real-time decision support,Reference Rainisch, Meltzer, Shadomy, Bower and Hupert16,Reference Walden and Kaplan18 but they did not consider the atmospheric dispersion of anthrax spores. The studies that had more detailed atmospheric dispersion as part of the model could not be used for real-time support due computational requirements, the complexities of utilizing the model to generate data, and the need for expert technical support. Crucially, most models lacked validation using data from previous attacks. Specifically, only one out of 13 models was comprehensively validated using historical data, while others had no validation or very limited validation.Reference Rainisch, Meltzer, Shadomy, Bower and Hupert16

Discussion

There are few models available for estimating the outcome of a weaponized anthrax attack, and even fewer that account for atmospheric spore dispersion. The available models were designed for inhalational anthrax attacks and used multiple approaches in terms of atmospheric dispersion, age-dependent dose response, disease progression, and spatial distribution. Some of this provides a series of parameters that would be useful to estimate the attack size and for decision making. For policy makers and responders, modelling can assist with estimating the affected area of contamination, and the resulting requirements for prophylaxis, vaccination, and decontamination. A model that uses some form of dispersion modelling would give the best estimate of this, especially if wind conditions, weather, and topography are considered. Models which do not use these parameters may under-estimate or over-estimate contamination, depending on the specific context. An important factor to consider is that most available anthrax attack modelling studies use very simplistic dispersion models, if at all, and lack thorough validation.

Validated atmospheric dispersion models are the most useful tools in determining anthrax concentration and extent of spread in case of such attacks. Although dispersion modelling requires complex meteorological data and is computationally intensive, it is useful in calculating the anthrax spore concentration at the location of interest, to best inform decision making and health response. Estimation of anthrax concentration using dispersion modelling is also useful in predicting individual exposure levels, allowing estimation of the point probability of infection over time.

The key parameters involved in the studies that include anthrax dispersion as part of their model are the number of spores released; release time; release location; volume of inhaled spores; population densities; and meteorological conditions such as the temperature, humidity, speed, and direction of wind. Dependence on these many parameters make it imperative to use comprehensively validated models to estimate spore concentrations, and to avoid over-estimating or under-estimating the dispersion.

Determining the extent of potential exposure in real-time during an airborne attack is challenging. The only model specially designed for this purpose employs a Bayesian approach for real-time and instant estimates of attack time and size based on incubation period and probability of infection.Reference Walden and Kaplan18 However, this model was developed for a simple point-source outbreak at a particular time. Consequently, while such simplistic models may be more usable for real-time decision support, their outputs may not be very informative or erroneous; conversely complex models may be informative and accurate, but difficult to use effectively during an event due to time constraints, and technical requirements of utilizing the model. This balance between utility, usability, and complexity has previously been reported.Reference Heslop, Chughtai, Bui and MacIntyre23 In addition to the atmosphere dispersion modelling which could be applied in a Sverdlovsk-like airborne outbreak, modeling of dispersion of anthrax in enclosed spaces (such as spore-laden envelopes in postal systems) is an important alternative approach to investigate the aerosol hazard in possible Amerithrax-like events. To date, the available models measured the aerosol dynamics of spores released from envelops in a mail room using Bacillus atrophaeus, a simulant for anthrax spores,Reference Ho and Duncan11 and analyzed the transmission of anthrax spores through the postal system by contaminated letters.Reference Webb and Blaser19 The key parameters included the volume of spores in each envelop, the number of letters with spores and cross-contaminated letters, postal nodes, and the number of inhalational anthrax cases among recipients. These models would provide a general framework to inform mitigation of a mail-borne anthrax attack, or similar methodology.

A major challenge in developing good models is the lack of validation data. Specifically, the only two well-studied sources of real anthrax data for validation of models are the Sverdlovsk accident, which more closely approximates an aerosol release, and the Amerithrax mail attack.Reference Meselson, Guillemin and Hugh-Jones5,Reference Jernigan, Raghunathan and Bell6 However, only seven models in this review used the Sverdlovsk and/or Amerithrax data. Proxies for an anthrax attack can also be used, including the New York subway experiment with Bacillus atrophaeus spore-loaded lightbulbs.Reference Army24 However, no atmospheric dispersion models utilized proxy data, and a number of models lacked validation entirely.

The public health impact of an attack, even if it causes few cases, can be substantial. In the anthrax attack in the US in 2001, despite only 22 cases and five deaths, over 32,000 people required antibiotic prophylaxis in New Jersey alone.Reference Bresnitz and Ziskin25 In an aerosolized attack, a much larger radius of exposure would be expected than a mail attack, and correspondingly, PEP may need to be far more wide-spread. A well-designed attack model of anthrax dispersion incorporated with intra-host germination of anthrax spores and intervention modelling would allow more confident estimation of affected populations, likely areas of contamination or exposure, and likely health outcomes, thus supporting real-time decision making. None of the reviewed models provided this combination in this study.

Limitations

Apart from limitations of the reviewed models, the main limitation of this study was that there may be some missing modelling approaches. The modelling from non-English sources, unpublished studies, and databases except for Medline, Web of Science, and Scopus may not be included in this systematic review.

Conclusion

There are a limited number of modelling studies available to inform public health decision making and response to an anthrax attack. The studies reviewed here use widely varying methods, assumptions, and data, which impact their relative strengths, limitations, and utility during an event. Models which include dispersion are more likely to provide an accurate estimate of the extent of contamination and exposure. However, current gaps include lack of validation of some models, lack of data for validation, lack of models incorporated with intra-host germination of anthrax spores and intervention modelling, and missed opportunities for the use of proxy data. A combination of modelling approaches is likely to provide the balance between accuracy, timeliness, and utility for real-time decision support for stakeholder needs. This, coupled with modelling of the likely health impact of an anthrax release, best informs a systematic public health response.

Conflicts of interest/funding

Thanks to the funding provided by the Australian National Health & Medical Research Council of Australia (NHMRC; Canberra, Australia), Centers of Research Excellence (CRE) grant (APP1107393). C Raina MacIntyre is also supported by a NHMRC Principal Research Fellowship, grant number 1137582. All authors declare that they have no competing interests and have no non-financial interests that may be relevant to the submitted work.