Introduction

Background

One of the most important issues in managing mass-casualty incidents (MCIs) is the distribution of casualties to appropriate health care facilities.Reference Bloch, Schwartz and Pinkert 1 In areas in which there are several hospitals, inappropriate distribution of casualties may result in patient overload in one institution, or admission of patients to facilities that lack appropriate resources to treat them.Reference Sockeel, De Saint Roman and Massoure 2 In an MCI that occurs in a remote area in which medical facilities are limited, defining the optimal destination for the casualties is of crucial importance.Reference Bloch, Schwartz and Pinkert 1 Studies have recommended that all immediate and moderate casualties be evacuated to the hospital closest to the site of event for advanced, hospital-based resuscitation, even though this may result in overtriage.Reference Bloch, Schwartz and Pinkert 1 , Reference De Cebballos, Fuentes and Diaz 3 , Reference Schwartz, Pinkert and Leiba 4

Improvement in air evacuation services have significantly upgraded the ability of Emergency Medical Services (EMS) to evacuate rapidly MCI casualties that occur in distant areas to tertiary care facilities.Reference Assa, Landau and Barenboim 5 Critical care air transport of casualties to distantly-located medical centers has been successfully utilized in disaster management in the United States, and in combat settings.Reference Beninati, Meyer and Carter 6

A study of severely-wounded military personnel in Afghanistan evacuated to distantly-located hospitals found that casualties experienced no adverse outcomes, even though arrival times ranged from one and a half to two hours.Reference Cordell, Cooney and Beijer 7 The current doctrine of the United States military in Iraq is to evacuate casualties to medical facilities remote from the conflict zone.Reference Mason, Eadie and Holder 8

Providing optimal medical care to casualties of MCIs that occur in remote areas should be based on identification of appropriate evacuation destinations.Reference Auf der Heide 9 There has been a long- standing debate about whether first responders should evacuate casualties to the nearest medical facility (provide basic life support (BLS) and rapid evacuation) or whether they should be capable of providing Advanced Life Support (ALS), such as intravenous line placement, endotracheal intubation, and cricothyrotomy on site.Reference Hoejenbos, McManus and Hodgetts 10 Evacuating casualties directly from the site of the event to distantly located Level I trauma centers may result in improved outcomes, if required treatment is rapidly provided, onsite or en route to the hospital.Reference Hoejenbos, McManus and Hodgetts 10 Increased attention should be given to improving prehospital trauma life support and evacuation of casualties to distantly located surgical facilities.Reference Gerhardt, De Lorenzo and Oliver 11

Management of remote MCIs raises an important question: should all casualties be transferred to the nearest hospital, regardless of its resources, as opposed to the evacuation of casualties to tertiary medical centers located at a distance from the site of the event?Reference Frykberg 12 A limited capacity peripheral hospital most likely will be overwhelmed if required to admit large numbers of casualties in a short period of time. Medical and manpower resources of the hospital might prove to be a bottleneck, negatively impacting patient care.Reference Sockeel, De Saint Roman and Massoure 2

In order to manage large-scale MCIs in peripheral hospitals in Israel, the policy of operating primary triage hospitals was introduced and implemented. Accordingly, in such MCIs, the admitting hospital provides only lifesaving procedures, stabilizes the casualties, and evacuates them to secondary or tertiary hospitals for definitive care.

The aim of this study was to review consequences of casualties’ evacuation from a remote MCI to a single medical facility, and to identify lessons relating to patient evacuation plans.

Description of the Event

A bus with 50 passengers overturned in a remote area, 14 kilometers from a 65-bed hospital. The distance to the next closest hospital was over 200 kilometers. Immediately following the bus accident, first responders, air evacuation teams, and the closest hospital to the site were alerted that an MCI had occurred. Civilian EMS in the area was limited; there were however, a number of military bases with EMS services. Local prehospital teams were reinforced by medical personnel from other regions. Twenty of the 50 bus passengers were pronounced dead on site; the driver and remaining 30 casualties were transferred to the 65-bed facility that operated as a “triage hospital.”Reference Peleg and Kellermann 13 This facility has eight emergency department (ED) beds, three operating rooms, four intensive care beds, and 30 physicians, two of whom were senior surgeons. Due to its isolated location, the hospital's staff was trained in Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS). Additional supplemental hospital staff in an MCI were community-based physicians and physicians who were vacationing in the town.

Casualties received initial lifesaving treatment at the triage hospital, including intubation, laparotomy, thoracotomy and needle thoracostomy, and subsequently were evacuated by air to four Level I and one Level II trauma centers. Helicopter arrival time from the closest airbase to the event site or the first admitting hospital was 64 minutes. Helicopters’ evacuation times from primary to secondary receiving hospitals ranged from 45 to 85 minutes. A fixed-winged aircraft also was utilized in the evacuation process. Arrival time for this mode of transport was three hours; flying time from the airport located in the region to the airport nearest the secondary hospitals was approximately 50 minutes, with an additional 15 minutes for ambulance evacuation of casualties to secondary hospitals.

Methods

Following the hospital's Institutional Review Board approval, as well as authorization from the Ministry of Health, the medical records of all casualties involved in the MCI were collected from both the primary and tertiary hospitals at which they were admitted and treated. All documents that were in the medical file were photocopied, including those documented in the ED, operating rooms, imaging, or laboratories. The medical records were reviewed by two experienced trauma surgeons. They reviewed times of primary and secondary evacuation, injury severity, triage decisions, diagnoses, surgical treatments, resources utilized, and final outcomes of patients at discharge from the tertiary care hospital. The hospital's triage system consisted of classifying each admitted casualty as urgent (injury that necessitates immediate care) or ambulatory (lightly injured), and treatment sites were deployed respectively.

All medical decisions were reviewed with regard to appropriateness for patients’ needs and availability of medical and surgical resources in the primary hospital. Triage decisions were reviewed in comparison to Injury Severity Score (ISS) calculated based on the description of injuries included in the patients’ charts. Undertriage was defined in cases where casualties with ISS > 9 were referred to the Ambulatory site. Overtriage was defined in cases where casualties with ISS < 8 were referred to the Urgent site. Following the independent review of the trauma surgeons, an additional review of the treatment was conducted by four senior trauma surgeons and their findings were compared to those of the two original surgeons. Reviewers gave special attention to actions taken during the initial treatment phase provided in the primary hospital, and their impact on patient outcomes.

Results

The reviews of the two trauma surgeons were compared to determine inter-rater reliability and were found to be in agreement. The additional review of the data was conducted jointly by the four senior trauma surgeons, thereby achieving full consensus.

Distribution of Casualties

Distribution of the 51 casualties is presented in Figure 1. Number and type of personnel utilized in the evacuation process is presented in Table 1. Thirty-one casualties were transferred by ambulances to the closest hospital; 20 passengers pronounced dead on site were transferred directly to the Forensic Medical Institute. Two casualties died en route to the local hospital; two died in the hospital within 30 minutes of arrival. Twenty-seven casualties were evacuated by air from the local hospital to Level I and II hospitals by helicopter or air carrier.

Figure 1 Severities of Casualties According to ISS (N = 51) Abbreviations: ISS, Injury Severity Score

Table 1 Personnel and Medical Resources Utilized On Site and for Secondary Aerial Evacuation

Abbreviations: ALS, Advanced Life Support; BLS, Basic Life Support; EMT-P, emergency medical technician-physician

aBLS military ambulances include physicians.

Times of Evacuation to Primary and Tertiary Facilities

Times of arrival at the primary and secondary hospitals are presented in Figure 2. All casualties arrived at the primary hospital within 60 minutes of occurrence of the accident. Within 40 minutes, 10 casualties arrived at the hospital; five were severely injured.

Figure 2 Times of Arrival to Primary and Secondary Hospitals (N = 27)

Arrival of casualties to tertiary care hospitals ranged from 2.26 to 6.15 hours. Of the 10 immediate casualties, four arrived at the tertiary hospital in under three hours; four within three to five hours; and two after more than five hours. In the case of the less-severely injured, one arrived in under three hours; two within three to five hours, and 14 were evacuated by the C-130 air carrier and arrived after five hours.

Triage of Casualties and Medical Services Utilization

Primary triage was performed on site by physicians and paramedics; secondary triage was performed at the entrance to the peripheral hospital by a physician (specialists in gynecology or anesthesiology). Appropriateness of triage decisions and extent to which medical services were utilized in the primary hospital are presented in Table 2. One patient died following surgery in the primary hospital. Two of the casualties who initially were triaged as mildly injured were subsequently reclassified and transferred to the immediate casualty site.

Table 2 Triage Decisions and Medical Services Utilization in the Primary Hospital for the 27 Surviving Casualties

Abbreviations: CT, Computerized Tomography; FASTs, focused assessment with sonography for trauma; ICU, intensive care unit; OR, operating room

aIncluding 10 FASTs, three CT scans, and 17 X-rays.

bICUs are usually not utilized when the facility is activated as a “triage hospital.”

None of the casualties were sent to the intensive care unit (ICU) in the primary hospital. Four of 27 casualties did not receive treatment that might have improved their conditions, due to nonidentification of a significant injury (eg, pneumothorax that was subsequently diagnosed), or due to failure to provide appropriate treatment for injuries identified (eg, shock, chest injuries or suspected pneumothorax.) Twenty-two imaging procedures were requested and in 17 (77%) cases, they were repeated at the tertiary hospital.

Medical Procedures in Primary Hospital

Lifesaving procedures performed at the primary hospital consisted of: six endotracheal intubations (one was a redo of field intubation); insertion of six chest tubes; two central lines; two traction splints for femur fractures; and one emergency laparotomy. Most of these procedures were performed by local staff; the reinforcing physicians who arrived at the hospital operated in collaboration with and under the supervision of the hospital's chief surgeon and head of the ED.

Discussion

The two approaches to providing prehospital care to trauma victims, BLS and rapid evacuation techniques (formerly referred to as “Scoop and Run”) and ALS technique (formerly referred to as “Stay and Play”), have been discussed extensively.Reference Hoejenbos, McManus and Hodgetts 10 Considering the different needs and available resources to deal with MCIs in urban and remote areas, it was concluded that medical systems should be flexible in order to respond to specific situations.Reference Hoejenbos, McManus and Hodgetts 10

Triage of Casualties in the Primary Hospital

Different triage mechanisms, such as the Simple Triage and Rapid Transport (START) or Sort, Assess, Lifesaving Interventions, Treatment/Transport (SALT) are susceptible to the problem of over and undertriage.Reference Lee 14 There is a need to reduce undertriage without increasing overtriage in order to avoid overutilization of vital resources.Reference Matsuzaki, Fernando and Marasinghe 15

Undertriage during MCI may have significant negative consequences for patients, while overtriage may result in investing vital resources for treating patients who do not require them.Reference Frykberg 12 It has been suggested that undertriage lower than five percent is acceptable in MCIsReference Sharma 16 and that an overtriage rate of 30%-50% is necessary to maintain an undertriage rate of less than 10%.Reference Davis, Dinh and Roncal 17

In this study, analysis of the triage carried out on arrival at the primary hospital showed that six (22%) of the casualties were triaged inappropriately; of these, four (15%) were undertriaged.

The problem with triage in the primary hospital may have resulted from limited trauma- related experience of the triage physicians. The senior surgeons were involved in providing care to the severely-injured patients and also functioned as managers (determined evacuation priorities and supervised medical care). A total of 24 physicians from the primary hospital were available at the time of the accident, but most of them lacked the experience required for managing trauma patients, even though many of them participated in ATLS. Hospital-based physicians were supplemented by 15 physicians from the community and seven who happened to be vacationing in the area. These visiting physicians, however, also lacked trauma management skills and were unfamiliar with the hospital structure.

Essential Medical Treatments Administered to Casualties

Ten of the casualties reviewed had an ISS >25. A number of the procedures provided in the primary hospital could have been carried out on site by first responders. Former reviews of care provided by surgeons in the primary hospital showed that they were competent in treating trauma patients. Review of the treatment provided to immediate casualties in this incident showed that in some cases essential care was not provided. This may be attributed to the fact that the hospital was overwhelmed by the arrival of 31 casualties. Had only the unstable casualties needing lifesaving treatment been transferred to the hospital, the available manpower could have focused only on these patients.

The significant number of imaging procedures carried out in the primary hospital had little impact on the medical decision making. Conducting medical procedures not immediately needed may have delayed transfer of casualties to secondary hospitals.

Issues Related to Transfer of Patients to Tertiary Hospitals

The site of the accident was 14 kilometers from the primary care hospital. In terms of flying times, the closest tertiary care hospital was 109 minutes and the furthest was 150 minutes.

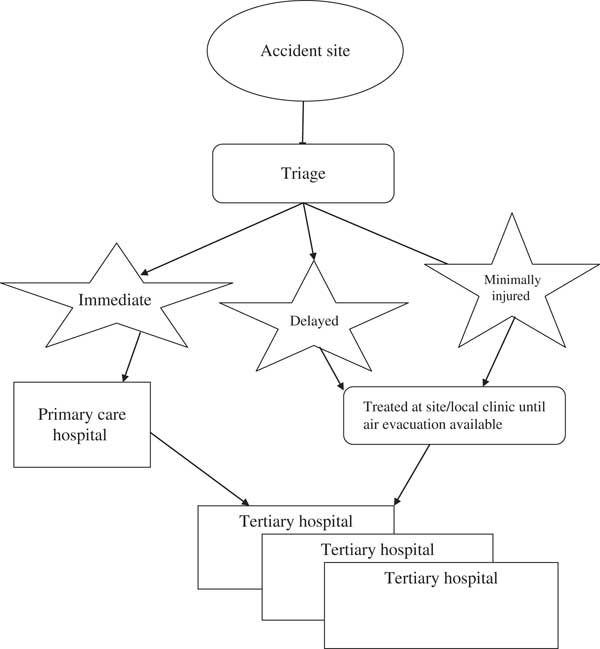

There are three main options to manage a mass casualty in a remote area: 1) evacuate all patients to the local hospital (may result in overwhelming of the hospital and thus critical/severe casualties may not receive optimal care); 2) evacuate only critically injured to the local hospital (may result in delay of care for light casualties); or 3) parcel out casualties to distant and nearby hospitals (may result in deterioration of critical casualties). Figure 3 outlines the recommended algorithm for managing casualty evacuation in an MCI occurring in an area which has limited medical facilities. Taking into account that transferring all casualties to the primary hospital resulted in essential medical treatment not being provided, due to overwhelming the facility, mild and delayed casualties should not be transferred to the closest hospital. They should rather be held on site and provided with BLS treatment until air evacuation resources are available to transfer them directly to more distant trauma facilities. Support for this approach may be found in the fact that medical procedures provided to mild and moderate casualties in the hospital may have been administered by medical personnel on site. More so, use of aerial evacuation to transport adult trauma casualties was found to be associated with reduced mortality.Reference Sullivent, Paul and Wald 18 Only immediate, unstable casualties should be evacuated to the closest hospital, and following stabilization and lifesaving treatments, should be transferred to tertiary hospitals for definitive care.

Figure 3 Proposed Casualty Evacuation Process in a Distant MCI

Abbreviations: MCI, mass-casualty incident

Ability to implement a policy of transporting only immediate patients to primary hospitals is dependent on whether the EMS teams have the necessary skills to provide BLS and ALS therapies on site. Emergency Medical Services personnel must be trained to perform procedures such as monitoring pulse oximetry, capnometry, intravenous fluid administration, and endotracheal intubation if this approach is to be implemented successfully.Reference Sharma 16 , Reference Davis, Dinh and Roncal 17 Even though EMS training provides for the performance of these skills, studies have reported that the number of opportunities that EMS technicians have to perform these procedures in the field is limited and may not allow for sufficient proficiencies to be maintained.Reference Davis, Dinh and Roncal 17 – Reference Gerbeaux 20 It is therefore essential to train EMS personnel and maintain proficiency in these skills.

Limitations

Detailed medical records are reported at the hospital level only; therefore, only limited clinical reports were accumulated from first responders that operated on site. It should be noted that all medical records were photocopied from the admitting hospitals; there were no missing data or lack of consistency regarding the medical procedures that were administered to the casualties.

Conclusions

Evacuation of casualties from an MCI to a hospital with a limited surge capacity may overwhelm the facility and affect its ability to provide appropriate medical care. Based on this study's findings, efforts should be made to improve prehospital trauma life support capacities. Policy makers should consider review of current evacuation plans in MCIs occurring in remote areas, examining the possibility of evacuating only immediate and unstable casualties to the closest primary care facility. Other casualties might be treated on site or evacuated to alternative holding points until they can be evacuated directly to distant hospitals. It should be stressed that implementing this policy requires availability of well-trained first responders in remote areas as well as competent and equipped air transport teams. Training EMS personnel should focus on triaging, providing BLS, and on-site monitoring of casualties until evacuation resources are available. In events in which there are limited numbers of casualties, the BLS and rapid evacuation approach may still be applicable. However, it is hypothesized that in case of MCIs in a remote underserviced area, it is more appropriate to adopt on-site ALS for those not severely injured, and BLS and rapid evacuation approach for the severely injured.

Author Contributions

Bruria Adini designed the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. Robert Cohen assisted in writing the manuscript. Elon Glassberg analyzed the patient charts and reviewed the manuscript. Bella Azaria designed the study and reviewed the manuscript. Daniel Simon analyzed the patient charts and reviewed the manuscript. Michael Stein reviewed the manuscript.

Yoram Klein reviewed the manuscript. Peleg Kobi supervised the conduct of the study, analyzed the data, and reviewed the manuscript.