Introduction

In a cold, wet, or windy environment, an injured or ill person often is exposed to considerable cold stress.Reference Danzl and Auerbach1–Reference Tisherman and Peitzman3 Heat loss, aggravated by clothing that is torn, wet or insufficient for ambient conditions, occurs primarily due to convection by warming of the surrounding air layer, and is greatly increased by wind or movement. If the injured or ill person is in direct contact with the ground or another cold surface, there may also be a significant conductive heat loss. In the case of wet clothing or skin due to immersion, precipitation or previous physical activity, body surface evaporative heat loss may be considerable. To a smaller extent, heat also is lost by radiation to cold objects in the surroundings or clear sky, and by evaporative heat loss from the airways.Reference Hassi, Mäkinen and Holmér4,Reference Holmér and Shishoo5

If total heat loss, W/m2 (W = Watts, m2 = body surface area), exceeds possible endogenous heat production (basal metabolism and shivering), there is a risk of whole body cooling and hypothermia. Cold-induced stress response may render great thermal discomfort,Reference Robinson and Benton6,Reference Lundgren and Henriksson7 and independent of injury severity, hypothermia at admission to the Emergency Department significantly increases the risk of death and comorbidity.Reference Gentilello, Jurkovich and Stark8–Reference Ireland, Endacott and Cameron14 Thus, in addition to immediate care for life threatening conditions, early application of adequate insulation to reduce heat loss and prevent body core cooling is an important part of prehospital trauma care.Reference Mills15,Reference Giesbrecht16

The heat retention capacity of an insulation ensemble depends on its thermal and evaporative resistance.Reference Holmér and Shishoo5 Thermal resistance (Rt), measured in m2°C/W (°C = degrees Celsius, W = Watts) or clo units (1 clo = 0.155 m2°C/W), is defined as the resistance to dry heat loss by convection, conduction, and radiation, and depends mostly on the thickness of the ensemble and its ability to retain air. Evaporative resistance (Re), measured in Pa m2/W (Pa = Pascal), is defined as the resistance to wet heat loss by evaporation of moisture through the material. Depending on the water vapor pressure gradient between skin and the surrounding air (defined by humidity and temperature), and on the moisture permeability of the insulation ensemble, the water vapor will either evaporate through the ensemble to the environment (real evaporation), or condense back to water within outer parts of the ensemble (the heat pipe effect).Reference Haventih, Richards and Wang17 In addition, wetting of the clothing and the surrounding insulation material will reduce its ability to retain air, thereby reducing thermal resistance and increasing heat loss due to wet conduction within the insulation ensemble.Reference Meinander18,Reference Meinander19

The thermal and evaporative resistance of an insulation ensemble, and thus dry and wet heat loss in a given ambient condition, can be determined using full-size thermal manikins in climatic chambers.20–23 Results from such manikin measurements have shown good reproducibility and agreement with human wear trials, and the values obtained can be used in physiological models for prediction of required insulation in different ambient conditions.Reference Anttonen, Niskanen and Meinander24–Reference Kuklane, Gao and Holmér27

If the patient is wet, most prehospital guidelines on protection against cold recommend the removal of wet clothing prior to insulation, and some also recommend the use of a waterproof vapor barrier between the patient and the insulation in order to reduce evaporative heat loss.2,Reference Durrer, Brugger, Syme and Elsensohn28–Reference Johnson, Anderson and Dallimore31 In the field, however, the ability to remove wet clothing might be impeded due to harsh environmental conditions or the patient’s condition and injuries. Also, encapsulation in a vapor barrier might restrict necessary access and monitoring of the patient during transport.

Previous studies on evaporative heat loss have focused on evaporative resistance in different clothing ensembles or sleeping bags in regards to the outer cover being permeable or impermeable.Reference Haventih, Richards and Wang17,Reference Lotens, Havenith and van de Linde32–Reference Wang, Kuklane and Gao34 However, no scientific studies have specifically evaluated the effectiveness of wet clothing removal or the addition of a vapor barrier as an inner layer under different levels of insulation.

Simulating a prehospital rescue scenario by using a thermal manikin in wet clothing, this study was conducted to determine the effect on thermal insulation and evaporative heat loss of wet clothing removal or the addition of a vapor barrier inside different amounts of insulation in both warm and cold ambient conditions.

Methods

Design and Settings

The study was carried out in September 2009 at the Thermal Environment Laboratory, Lund University, Lund, Sweden. A thermal manikin was used to evaluate the effect of wet clothing removal or the addition of a vapor barrier inside three different levels of insulation in cold and warm ambient temperatures.

The climatic chamber (2.4 × 2.4 × 2.4 m) and the thermal manikin TORE22,Reference Kuklane, Heidmets and Johansson35 were set up in accordance with the European Standard for assessing requirements of sleeping bags, modified for wet heat loss determination.20 A rigid wooden board (194 × 60 × 1.6 cm) was positioned in the middle of the climatic chamber supported approximately 85 cm above the ground on a metal framework placed on a large scale (KC240, 240 kg, ± 5g, Mettler-Toledo Inc., Greifensee, Switzerland). To simulate a prehospital rescue scenario, the thermal manikin was then placed in a supine position on an ordinary plastic spineboard (Baxstrap, 184 × 39 × 2.5 cm, Laerdal Medical AS, Stavanger, Norway) on top of the wooden board.

The thermal manikin is the size and shape of an average male, with a height of 171 cm and 1.8 m2 body surface area. The manikin is divided into 17 segments representing specific body parts, with independent internal electrical heating and surface temperature sensors enabling area-weighted heat flux recordings. Surface temperature was set and calibrated at 30.0±0.1 °C and 13 humidity sensors (SHT75 sensors with evaluation kit EKH3, ±2% relative humidity, Sensirion AG, Staefa, Switzerland) were placed over the legs, arms and trunk of the manikin.

The climatic chamber was set to -15 °C for cold environment measurements and +10 °C for warm environment measurements. Ambient air temperature sensors (PT 100±0.03 °C, Pico Technology Ltd, St. Neots, UK) were positioned level with the supine manikin, adjacent to the ankles, mid-trunk and head.

The manikin clothing consisted of light, two-piece thermal underwear, knee-length socks, and a balaclava. Pre-trial measurements were conducted with dry clothing and three different insulation ensembles; one, two or seven woollen blankets (Swedish Rescue Forces surplus), were chosen to provide low (2.81±0.08 clo), moderate (3.78±0.07 clo) or high (5.85±0.18 clo) insulation in still wind conditions at -15 °C.26,Reference Henriksson, Lundgren and Kuklane36 Each blanket measured approximately 190×135×0.5 cm and weighed 2,000 g. The vapor barrier was made up of two large plastic bags, taped together to form a large sack (250×85 cm, 250 g).

Protocol and Monitoring

Five different test conditions were evaluated for all three levels of insulation ensembles: (1) no underwear; (2) dry underwear; (3) dry underwear with a vapor barrier; (4) wet underwear; and (5) wet underwear with a vapor barrier. The trials with dry or no underwear (1–3) were conducted only in cold conditions, while the trials with wet underwear (4 and 5) were conducted in both cold and warm conditions. This is due to the fact that in dry conditions, thermal resistance will be the same regardless of ambient temperature. Thus, dry heat loss in different ambient temperatures can be calculated from the determined thermal resistance. In wet conditions, however, evaporative heat loss will differ due to different water vapor pressure and dew point location in clothing and insulation layers at different temperatures. Thus, wet heat loss needs to be determined for each specific ambient temperature. All test conditions were repeated and evaluated twice for each level of insulation in a randomized order, resulting in a total of 42 scheduled trials.

Prior to and between the trials, manikin clothing and insulation materials were kept dry and at room temperature. Each trial then began with the supine manikin being dressed in dry, wet or no clothing according to the protocol. The wet clothing was provided by a standardized rinsing program using an industrial washing machine. If assigned, the vapor barrier sack was then pulled over the manikin from the feet up and tightly folded around the neck. Finally, the assigned numbers of woolen blankets were applied on top of the manikin from the neck down, and separately folded tightly under and in between the manikin and the spine board.

Manikin surface temperature, heat loss, and ambient air temperature were then continuously recorded for approximately 60 minutes until steady state thermal transfer had been established and stable for 20 minutes. In wet conditions, evaporation was monitored by manikin surface and ambient air humidity together with continuous weighing (0.1 Hz) of the whole setup.

Data Analysis

Continuous monitoring of area-weighted heat flux recordings and the gradient between ambient air and manikin surface temperature (°C) during the last 10 minutes of steady state heat and mass transfer were used to determine total heat loss, Q tot (W/m2), and thermal resistance, Rt (m2°C/W), for the different conditions (calculated using the parallel method).22 In dry conditions, there is no wet heat loss and thus total heat loss equals dry heat loss, Q dry (W/m2). From the known thermal resistance in cold conditions, dry heat loss for the same level of insulation in warm conditions was calculated. Wet heat loss, Q wet (W/m2), was determined as the difference between total heat loss in wet and dry conditions. The proportion of wet heat loss due to real evaporation, Q evap (W/m2), was calculated from the mass loss rate (g/m2*s) at steady state and the enthalpy of evaporation (J/g), enabling the calculation of wet heat loss due to the heat pipe effect, Q heatpipe (W/m2); i.e., evaporation and condensation within the ensemble, where Q tot=Q dry+Q wet=Q dry+Q evap+Q heatpipe.Reference Haventih, Richards and Wang17

After each set of repeated trials, the thermal resistance variation coefficient (standard deviation/average thermal resistance) was analyzed and the trials repeated for values exceeding five percent.Reference Anttonen, Niskanen and Meinander24 Results are reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and thermal resistance is converted to clo units (1 clo = 0.155 m2°C/W).

Results

After initial trials and protocol adjustments, a total of 42 trials were scheduled. Of these, three trials were repeated due to exceeded thermal resistance variation coefficient limits, resulting in a total of 45 conducted trials. The average thermal resistance variation coefficient was 1.8±1.0% for the accepted set of repeated trials. Ambient air temperature was -15.4±0.4 °C in the cold conditions and +11.0±0.1 °C in the warm conditions. Average wind speed was 0.22±0.07 meters per second (m/s) for all conditions. Manikin clothing dry weight was 615 g. In wet conditions, the water content in the underwear at the beginning of each trial was 1,418±20 g.

Cold Environment

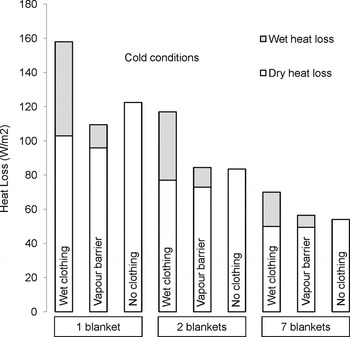

In the cold environment, depending on insulation thickness, wet heat loss accounted for 29–35% of total heat loss prior to wet clothing removal or the addition of the vapor barrier. Approximately half of this loss was due to real evaporation, and half was due to evaporation and condensation within the ensemble (Table 1, Figure 1).

Table 1 Thermal insulation and heat loss with or without wet clothing removal or the addition of a vapour barrier within different levels of insulation in cold (-15.4±0.4°C) and warm (+11.0±0.1°C) conditions (Values are mean ± SD, each based on two repeated measures on a thermal manikin.20)

a Ambient temperature (°C).

b Total resultant thermal insulation in clo-units (1 clo = 0.155 m2°C/W).

c Wet heat loss due to evaporation from the ensemble to the ambient environment.

d Wet heat loss due to evaporation and condensation (heatpipe) within the ensemble.

Figure 1 Heat loss (W/m2) in cold conditions (-15.4±0.4°C); wet clothing, wet clothing with a vapor barrier or wet clothing removed within one, two or seven woolen blankets

With the vapor barrier applied, dry heat loss decrease was 1–7%, the effect being more pronounced with less insulation. However, independent of insulation thickness, the addition of the vapor barrier significantly reduced wet heat loss, and thus rendered a total heat loss reduction of 19–31% compared to no intervention in wet conditions.

With the wet clothing removed, dry heat loss increased 8–19%, the effect being more pronounced with less insulation. However, independent of insulation thickness, wet clothing removal and thus wet heat loss elimination, still rendered a total heat loss reduction of 22–29% compared to no intervention in wet conditions.

Increasing the insulation from one to two or from two to seven woolen blankets, without wet clothing removal or the addition of a vapor barrier, rendered a total heat loss reduction of 26% and 40%, respectively.

Warm Environment

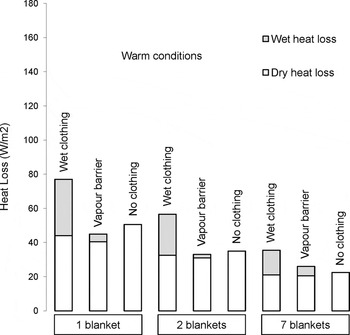

In the warm environment, depending on insulation thickness, wet heat loss accounted for 41–43% of total heat loss prior to wet clothing removal or the addition of the vapor barrier; the proportion of real evaporation increased from approximately one-third with high insulation to two thirds of wet heat loss with low insulation (Table 1, Figure 2).

Figure 2 Heat loss (W/m2) in warm conditions (+11.0±0.1°C); wet clothing, wet clothing with a vapour barrier or wet clothing removed within one, two or seven woolen blankets

With the vapor barrier applied, dry heat loss decrease was 2–8%, the effect being more pronounced with less insulation. However, independent of insulation thickness, the addition of the vapor barrier significantly reduced wet heat loss and rendered a total heat loss reduction of 27–42% compared to no intervention in wet conditions.

With the wet clothing removed, dry heat loss increased 7–15%, the effect being more pronounced with less insulation. However, independent of insulation thickness, wet clothing removal and thus wet heat loss elimination, still rendered a total heat loss reduction of 34–38% compared to no intervention in wet conditions.

Increasing the insulation from one to two or from two to seven woolen blankets, without wet clothing removal or the addition of a vapor barrier, rendered a total heat loss reduction of 26% and 37%, respectively.

Discussion

Overview

Independent of insulation thickness, wet heat loss accounted for about one-third of total heat loss in the cold environment, and almost half of total heat loss in the warm environment. Independent of insulation thickness, the removal of wet clothing or the addition of a vapor barrier rendered a reduction in total heat loss of about one fourth in the cold environment and about one third in the warm environment. A similar reduction in total heat loss was also achieved in both warm and cold conditions by increasing the insulation from one to two blankets or from two to seven blankets.

Possible Mechanisms for Results

At the same level of insulation, both dry and wet heat loss were greater in the cold environment than in the warm environment. Although heat loss from real evaporation through the insulation to the environment was about the same for a given amount of insulation regardless of ambient temperature, in the cold environment there was a substantial increase in wet heat loss due to evaporation and condensation within the ensemble, and increased conduction through layers. The proportion of wet heat loss to total heat loss was lower in the cold environment due to greater dry heat loss being present. This explains why wet clothing removal or the addition of a vapor barrier rendered relatively greater heat loss reductions in the warm environment. However, the absolute heat loss reduction was more pronounced with less insulation available, and greater in the cold environment.

Independent of insulation thickness or ambient temperature, the vapor barrier rendered only minimal increase in thermal resistance and thus dry heat loss reduction was small. However, by increasing the evaporative resistance and limiting evaporative heat loss, the addition of the vapor barrier resulted in a significant decrease in total heat loss.

Although wet, clothing still adds some thermal resistance to the ensemble. Thus, when the wet clothing was removed, dry heat loss was slightly increased, with the effect being more pronounced in the cold environment and with fewer blankets applied. However, independent of insulation thickness or ambient temperature, when the wet clothing was removed, wet heat loss was eliminated, rendering a significant decrease in total heat loss.

Independent of ambient temperature, increasing the insulation from one to two blankets or from two to seven blankets rendered a decrease in total heat loss comparable to wet clothing removal or addition of the vapor barrier by increasing both thermal and evaporative resistance, thus decreasing both dry and wet heat loss.

Practical Implications

In the prehospital care of a cold and wet person, early application of adequate insulation is of utmost importance to reduce cold stress, limit body core cooling and prevent deterioration of the patient’s condition.Reference Mills15,Reference Giesbrecht16 Most prehospital guidelines on protection against cold recommend the removal of wet clothing prior to insulation; some also recommend the use of a vapor barrier to reduce evaporative heat loss.2,Reference Durrer, Brugger, Syme and Elsensohn28–Reference Johnson, Anderson and Dallimore31 However, there is little scientific evidence of the effectiveness of these measures.

Using a thermal manikin, this study evaluates the effect of wet clothing removal or the addition of a vapor barrier in addition to different levels of insulation in warm and cold environments. The results indicate that, independent of ambient temperature or insulation thickness, wet clothing removal or the addition of a vapor barrier can reduce total heat loss by approximately one-fourth to one-third. The absolute reduction is greater, however, and thus clinically more important, in lower ambient temperatures when little insulation is available. The same effect also can be achieved by increasing the insulation applied. Depending on the ambient temperature, different levels of insulation thickness are required to maintain thermoneutrality.26 In a warm environment, this can be achieved using only a few blankets, whereas in a cold environment, several more blankets or thick rescue bags will be needed to limit heat loss and prevent body core cooling. Thus, if the patient can be transferred readily into a warm environment, such as a heated transportation unit, sufficient insulation is easy to achieve, and the need for wet clothing removal or the addition of a vapor barrier is limited. However, in a sustained cold environment with limited insulation available, such as in protracted evacuations or mass casualty situations in harsh conditions, the removal of wet clothing or the addition of a vapor barrier might be of great importance to reduce heat loss and improve both the thermal comfort and the medical condition of the patient upon admission to the Emergency Department.

Limitations and Future Research

This study provides thermo-physical data on how dry and wet heat losses are affected by wet clothing removal or the addition of a vapor barrier. The results may serve as an indicator of whether these measures should be considered in a prehospital rescue scenario. However, these results should be validated in human trials to correlate the effect of evaporative heat loss reduction to human thermoregulation and comfort.

Conclusions

Independent of ambient temperature or insulation applied, wet clothing removal or the addition of a vapor barrier substantially reduced total heat loss. The absolute reduction is greater, and thus clinically more important, in lower ambient temperatures when little insulation is available. However, the same effect was also achieved by increasing the insulation. Wet clothing removal or the addition of a vapor barrier might be of great importance in prehospital rescue scenarios in cold environments with limited insulation available, such as in mass-casualty situations or during protracted evacuations in harsh conditions.

Abbreviations:

°C = degrees Celsius

Pa = Pascal

RH = relative humidity

W = Watts