Introduction

External aortic compression (EAC) for temporary control of exsanguinating sub-diaphragmatic hemorrhage has long been an option for in-hospital management of non-traumatic hemorrhage, particularly obstetric,Reference Riley and Burgess1–Reference Soltan, Faragullah, Mosabah and Al-Adawy3 but has only recently been reported as effective in penetrating trauma, and in the field, when DoumaReference Douma, Smith and Brindley4 described the successful use of road-side manual aortic compression, delivered with a fist in the epigastrium, to manage catastrophic bleeding from an aortic gunshot wound. Subsequent work has discussed the difficulty in applying sufficient force to occlude aortic flow,Reference Blaivas, Shiver, Lyon and Adhikari5,Reference Douma and Brindley6 optimal techniques for doing so,Reference Douma and Brindley6 and the problems experienced in providing effective EAC during transport to hospital.Reference Douma, O’Dochartaigh and Brindley7 This paper’s authors work for a physician-led Emergency Medical Retrieval Service in South Australia, and have four times used manual EAC to manage catastrophic sub-diaphragmatic bleeding in the prehospital and transport setting. These cases, reported below, confirm that EAC has much promise as a first aid measure for managing such hemorrhage in the field. Approval for publication was granted by the responsible Health Authority’s Human Research Ethics Committee.

Case Report One

An adult male collapsed after receiving a single stab wound to the epigastrium, perforating both aorta and vena cava. In addition to the usual paramedic responders, a Medical Retrieval Team (MRT), comprising a physician and registered nurse, was dispatched to the scene. The first arriving paramedics found the patient unresponsive and pulseless, and commenced resuscitation, including drug-free tracheal intubation, bilateral needle thoracostomies, external cardiac massage, and crystalloid infusion via bilateral upper humeral intraosseous (IO) needles.

En-route to the scene, the MRT requested that EAC be applied. Upon arrival, approximately 40 minutes after injury, the patient was lying supine on an ambulance stretcher in the street. He was ashen and unresponsive, and being hand ventilated via an endotracheal tube. The end tidal CO2 measured 14mmHg. Cardiac massage had been ceased, and the only sign of life was sinus rhythm at a rate of 90 on the electrocardiogram (EKG). Ineffective EAC was being applied, with one hand, by a security guard from the side of the stretcher. The MRT physician immediately took over EAC, pressing down hard in the epigastrium using the right elbow supported by the left fist, and the patient was loaded for immediate road transfer to the hospital, departing the scene after four minutes. The MRT physician maintained EAC during the 30-minute road transfer to the hospital while sitting, unrestrained, on the attendant seat adjacent the stretcher. Despite operator fatigue, the technique appeared effective, as the patient’s color improved noticeably, end tidal CO2 rose to 20mmHg, and he began coughing on the tube, requiring neuromuscular blockade. Paramedics gave 500mls of 0.9% saline on scene and the MRT gave two units of red blood cells and 1,000mls of 0.9% saline during transfer.

Upon arrival at the hospital, the MRT physician climbed onto the ambulance stretcher astride the patient and continued EAC with a knee in the epigastrium while the patient was taken into the emergency room (ER). Compression was briefly lost during transfer to the ER gurney, which resulted in noticeable loss of color, then reapplied via elbow and fist until hemostasis was achieved by clamping the aorta at ER thoracotomy. The patient was then taken to the operating room (OR) with a viable circulation, but the injury proved irreparable, and he died during surgery.

Case Report Two

An adult female with an undiagnosed ectopic pregnancy self-presented to a small metropolitan hospital in the early hours of the morning, then collapsed in the emergency department reception area. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) was commenced, and a diagnosis of ruptured ectopic pregnancy was rapidly made. As the hospital did not have a surgical service, urgent transfer was sought while resuscitation proceeded. A physician/nurse MRT was dispatched by road, and the ER staff was instructed to apply EAC in the interim. The MRT reached the patient approximately 60 minutes after the collapse, finding her ashen, pulseless, and unresponsive, with mask ventilation, external cardiac massage, and fluid resuscitation in progress. The only sign of life was sinus rhythm at a rate of 80 on the EKG. A nurse was applying EAC, ineffectively, with one hand, from the side of the gurney, hence the MRT physician instructed that cardiac compressions cease, and the nurse instead climb onto the gurney astride the patient and press down hard with a knee in the epigastrium. This produced a moan and arm flexion from the patient.

The MRT intubated the patient, noting an initial end tidal CO2 of 28mmHg, and inserted an upper humeral IO needle as the best existing intravenous (IV) access was in the foot, below the site of aortic compression. The patient was loaded into a road ambulance for transfer to the surgical center. During the 15-minute road transfer, EAC was maintained by the MRT physician kneeling unrestrained, adjacent the ambulance stretcher and pressing hard into the epigastrium with one elbow, supported by the other fist. This caused severe rescuer fatigue and transient ulnar nerve symptoms. The MRT nurse manually ventilated via the endotracheal tube, and administered two units of red blood cells via the humeral IO, in addition to the four units of red cells which had been given by the first hospital.

Upon arrival at the surgical center, the MRT physician climbed onto the ambulance stretcher astride the patient and continued EAC with a knee while the patient was taken directly to the OR, before reverting to an elbow on the operating table. This was maintained while the surgeon achieved hemostasis via a lower midline laparotomy, and for a short time thereafter, until the anesthesiologist reported adequate fluid resuscitation had been achieved.

The patient was extubated, neurologically intact, on Day 2, but exhibited transient liver and kidney injury, requiring short-term dialysis. She was discharged home well and with no deficits on Day 18.

Case Report Three

An adult male sustained multiple stab wounds to head, neck, and abdomen. Paramedics arrived first, approximately five minutes after injury, to find the patient conscious but without palpable pulses. He deteriorated rapidly, and a physician/paramedic MRT arriving 15 minutes after injury found him unresponsive in the back of the ambulance, pulseless, but in sinus rhythm with a rate of 67 via EKG, having been intubated without drugs by paramedics. Blood pressure and oxygen saturations were unrecordable, and the pupils were non-reactive. Initial end tidal CO2 was 32mmHg. Finger thoracostomies were performed bilaterally, and external cardiac compressions commenced. Point-of-care ultrasound revealed a contracting heart with no evidence of pericardial effusion, therefore cardiac compressions were ceased.

Bilateral tibial IO lines were established and two units of red cells were infused via a fluid warmer. The circulatory response was poor, with end tidal CO2 declining to 25mmHg, then EAC was established by a paramedic with a single fist in the epigastrium, and the blood product infusion was swapped to a third IO line established in the left humoral head so as to access the circulation above the point of EAC.

At this point, the heart rate rose to 122 on the EKG, end tidal CO2 to 40mmHg, and the patient began to move his arms spontaneously. He was loaded into the road ambulance and transported to the trauma center, which had been notified previously, arriving approximately 40 minutes after injury. During transport, an un-seatbelted paramedic maintained EAC with a knee in the patient’s epigastrium, then changed to a supported fist for unloading and movement into the resuscitation room, where a nurse standing on a step took over, using a supported fist. End tidal CO2 was 43mmHg on arrival. A massive transfusion protocol was commenced and the MRT handed the patient over to the ER staff and withdrew from the resuscitation. They returned a few minutes later to find EAC discontinued, the patient without cardiac output, and Advanced Cardiac Life Support protocol CPR in progress. It appeared the ER team lacked the knowledge to manage exsanguinating hemorrhage temporized by EAC, and the patient was subsequently declared deceased in the ER.

Case Report Four

An adult male sustained a catastrophic lower limb injury after the flat fronted van he was driving impacted a tree head-on at high speed. Paramedics arrived first, five minutes after impact, to find him sitting upright, heavily trapped, and accessible only from the chest up. The Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) was 15, heart rate 90, and systolic blood pressure 150mmHg. Through gaps in the wreckage, it was evident that there were multiple open fractures of the right thigh and leg, with on-going bleeding which could not be reached for management, including via EAC or limb tourniquet. Pelvic and abdominal injuries were also suspected, but the head and chest appeared uninjured. Paramedics commenced 1,000mls IV saline infusion while awaiting release from the wreckage. A physician/nurse MRT arrived 25 minutes after the crash to find the patient deteriorating, with impalpable pulses, falling GCS, and pallor. One unit of packed red blood cells was started, but the patient continued to decline during rescue, becoming unresponsive, pulseless, and apneic two to three minutes prior to release, some 50 minutes after the crash.

Immediately upon release, the patient was placed on the ambulance stretcher and EAC applied by a paramedic using one fist supported by the other hand. This produced an immediate response, with a groan, eye opening, and respirations. Over several minutes, a pelvic splint was applied and tourniquets were applied to both lower limbs. A further unit of red cells and 1,000mls of normal saline was commenced via peripheral IV and upper humeral IO needle.

The patient was loaded into the road ambulance for transport, departing the scene 60 minutes after injury, and arriving at the trauma center 70 minutes after injury. Aortic compression was continued by the MRT physician using a single knee while travelling un-seatbelted in the back of the ambulance. The patient continued to improve en-route, at times opening his eyes and complaining about the pressure on his abdomen, but still with impalpable pulses and unrecordable blood pressure. Compression was continued into the ER using a supported fist, and was sustained in the ER until fluid resuscitation was achieved. The patient then went to the OR pink, self-ventilating, with GCS 14, systolic blood pressure 105mmHg, and heart rate 96. Subsequent investigation revealed that all significant injuries involved one leg, requiring multiple surgeries, and ultimately, above knee amputation. He was discharged to the rehabilitation center, neurologically intact, after 30 days.

Discussion

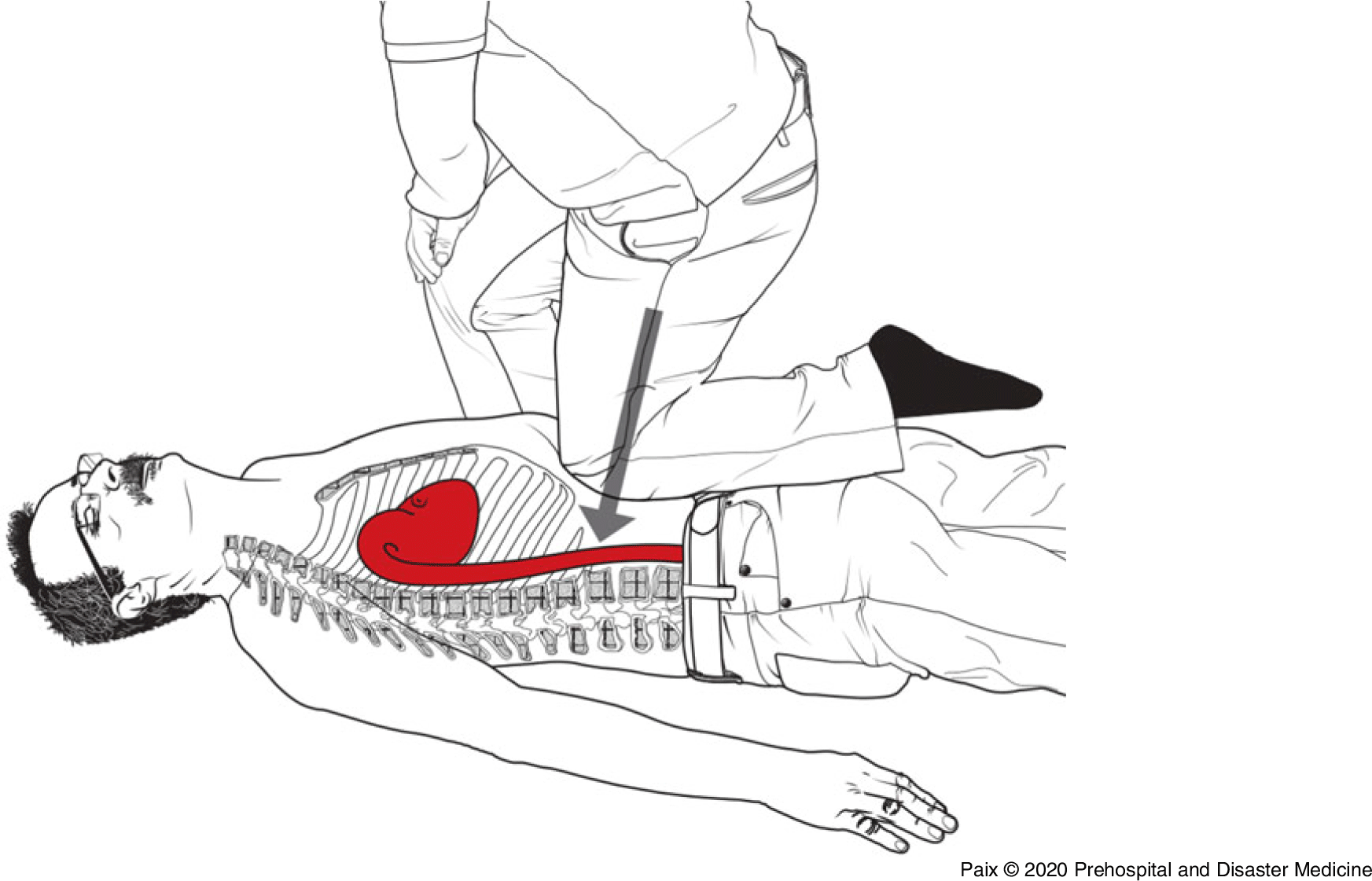

The presumed action of EAC is simply to occlude the aorta by direct compression against the vertebral column,Reference Douma, Smith and Brindley4,Reference Blaivas, Shiver, Lyon and Adhikari5,8 reducing on-going volume loss, but also to increase upper body blood flow and pressure.Reference Douma, Smith and Brindley4,8,Reference Kin, Hayashida and Chang9 Traditionally, EAC has been used to manage post-partum hemorrhage, and is applied by a single operator standing alongside the parturient and pressing down hard with a single fist over the lax upper abdomen.Reference Riley and Burgess1,8 Firm pressure is required, fatiguing for a single operator, and possibly requiring “rotation of compressors,” akin to CPR.Reference Riley and Burgess1 Successful occlusion of aortic flow in adult male volunteers with normal hemodynamics, however, appears more difficult, requiring 80–120lbs of downforce,Reference Blaivas, Shiver, Lyon and Adhikari5 which is only marginally feasible and very fatiguing, using single or two-handed methods.Reference Douma and Brindley6 Maximum and most sustainable downforce, at up to 80% of the compressor’s body weight, can be provided by placing the subject supine on a hard surface, at ground level, while kneeling astride the casualty and pressing down hard in the epigastrium with a single knee (Figure 1).Reference Douma and Brindley6,Reference Douma, O’Dochartaigh and Brindley7 All four cases presented here were grossly shocked at presentation, with impalpable pulses, hence it was not feasible to verify compression efficacy by confirming distal pulse loss. Of note, however, despite it being requested on two occasions that first responders “press down very hard in the epigastrium” while awaiting arrival of the MRT, none were doing so, but instead providing ineffectual EAC, one handed, from the side of the gurney. If EAC is to be introduced as a first aid measure for exsanguinating hemorrhage, education in the method is clearly required, both for health care workers and the general public. Popularization of EAC as a “knee ride,” or some other more self-explanatory phrase, might be beneficial, although the sometimes suggested “Knee-BOA” may lack popular recognition.

Figure 1. Manual External Aortic Compression May Best be Performed with a Knee.

The use of manually applied EAC during transport is problematic, with vehicle motion compromising compression efficacy, increasing operator risk, and fully occupying the rescuer to the exclusion of all other tasks.Reference Douma, Smith and Brindley4,Reference Douma, O’Dochartaigh and Brindley10 This paper demonstrated the feasibility of manual EAC during road ambulance transport on four occasions, with clear clinical improvement in three, but required a second rescuer to provide other care, un-seatbelted travel by the compressor, and produced severe fatigue and transient musculoskeletal and ulnar nerve symptoms in the compressor. If EAC is to be used during transport, a safe and effective “hands-free” method is required. The pneumatic Abdominal Aortic & Junctional Tourniquet (AAJT - Compression Works LLC; Birmingham, Alabama USA) appears promising in this setting,Reference Lyon, Shriver and Greenfield11,Reference Taylor, Coleman and Parker12 and it is currently being evaluated by the South Australian Ambulance Service. Such a device may also reduce the risk of circulatory dump during transfer from ambulance stretcher to resus or operating table, as seen in Case One, or when compressors change, but its bulk (much wider than a single fist) may limit subsequent hemostatic surgical options, and prevent very proximal aortic occlusion.

Vascular cannulation can be difficult in severely shocked patients, and lower body IV or IO access may be all that is initially available, but fluids so infused may be isolated from the upper body circulation if EAC also occludes the inferior vena cava. In two of the four cases reported, the best access was initially below the level of EAC, necessitating a change to the humeral IO route for resuscitation fluids and drugs.

While EAC may suffice to control bleeding from post-partum hemorrhage without the need for surgery,Reference Soltan, Faragullah, Mosabah and Al-Adawy3,8 for other causes, surgical hemostasis may be required. Approaches include laparotomy below the compressing fist,Reference Keogh and Tsokos2 laparotomy above the compressing fist,Reference Kin, Hayashida and Chang9 and resuscitative thoracotomy.Reference Douma, Smith and Brindley4 Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA) might be another option,Reference Biffl, Fox and Moore13 provided the catheter can be fed along the compressed aorta. In Case One, surgical hemostasis was achieved by ER thoracotomy; in Case Two, by laparotomy below the compressing fist; and it was not attempted in Case Three, with the patient instead declared dead in the ER, despite having signs of life on arrival, only minutes earlier. In Case Four, limb tourniquets ultimately proved sufficient to control the hemorrhage, but EAC appeared beneficial in restoring cardiac output before tourniquet application, and until vascular refilling was achieved.

Potential complications of EAC include re-animation of a combative casualty,Reference Douma, Smith and Brindley4 distal ischemic injury, mechanical visceral injury, and pain.Reference Soltan, Faragullah, Mosabah and Al-Adawy3,Reference Lyon, Shriver and Greenfield11 One porcine study suggested that up to 60 minutes of aortic occlusion by AAJT was tolerable.Reference Kheirabadi, Terrazas and Miranda14 One survivor did exhibit significant hepatic and renal dysfunction initially, but was discharged home well and neurologically intact; the other, with the shortest duration of EAC, also survived neurologically intact.

Conclusion

External aortic compression has apparent potential for temporizing exsanguinating sub-diaphragmatic hemorrhage in the field, and during transport to care. Maximizing efficacy requires an unbroken chain from point of injury to OR, beginning with the bystander’s knee, transitioning to a hands-free compression device for transport, and continuing until hemostasis and vascular refilling is achieved.

Conflicts of interest

none