Introduction

Hypotensive episodes, whether traumatic, peri-intubation-related, or resulting from septic shock, have been shown in both the emergency department (ED) and prehospital settings to increase both patient morbidity and mortality.Reference Almahmoud, Namas and Zaaqoq1-Reference Jones, Yiannibas, Johnson and Kline6 Prehospital hypotension is also quite common, occurring in almost five percent of critical ground-based transports and in over ten percent of Emergency Medical Services (EMS) transports involving mechanically ventilated patients.Reference Singh, MacDonald and Ahghari7,Reference Singh, Ferguson, MacDonald, Stewart and Schull8

Bolus dose vasopressors have been used successfully in the ED,Reference Panchal, Satyanarayan, Bahadir, Hays and Mosier9,Reference Swenson, Rankin, Daconti, Villarreal, Langsjoen and Braude10 as well as in the fields of anesthesia, pediatric critical care, and obstetrics, to quickly and effectively augment hypotension.Reference Hassani, Movaseghi, Safaeeyan, Masghati, Ghorbani Yekta and Farahmand Rad11-Reference Reiter, Roth, Wathen, LaVelle and Ridall13 Varying agents have been studied including phenylephrine, norepinephrine, epinephrine, and vasopressin. Due to the familiarity and ubiquity of epinephrine throughout EMS, this is an obvious potential pharmacologic solution. Epinephrine has the advantage of having both alpha-1 and beta-1 adrenergic receptor agonist effects yielding a combination of increased peripheral vasoconstriction, chronotropy, and inotropy.Reference Overgaard and DzavÌk14 Vasopressor use was long thought to require central venous access for administration, limiting prehospital usage. However, recent evidence demonstrates safety when administering vasopressors via peripheral access.Reference Cardenas-Garcia, Schaub, Belchikov, Narasimhan, Koenig and Mayo15

Within the prehospital literature, the evidence for bolus dose vasopressor use is limited to helicopter EMS (HEMS) and critical care transport servicesReference Nawrocki, Poremba and Lawner16,Reference Guyette, Martin-Gill, Galli, McQuaid and Elmer17 and has not been evaluated in a ground-based EMS environment. In this study, the efficacy of prehospital bolus dose epinephrine was assessed, and adverse events during transport were noted, in hypotensive (SBP<90mmHg), non-cardiac arrest patients by paramedics within a high-volume, ground-based EMS agency.

Methods

Study Design and Setting

This was a retrospective chart review of all EMS patient care records of subjects treated for acute hypotension with bolus dose intravenous (IV) epinephrine from September 12, 2018 through September 12, 2019 by a large, suburban, county-based EMS service in Texas (USA). The data review was a part of a quality improvement evaluation of a previously developed EMS protocol for the treatment of hypotension as defined by SBP <90mmHg. The EMS agency employs approximately 250 Advanced Life Support providers supported by over 1,000 Emergency Medical Technicians in 13 first responder organizations. The service area covers 1,100 square miles and responds to more than 70,000 annual calls for service. This study was approved by the Baylor College of Medicine (Houston, Texas USA) Institutional Review Board with a waiver of informed consent (Protocol H-46037).

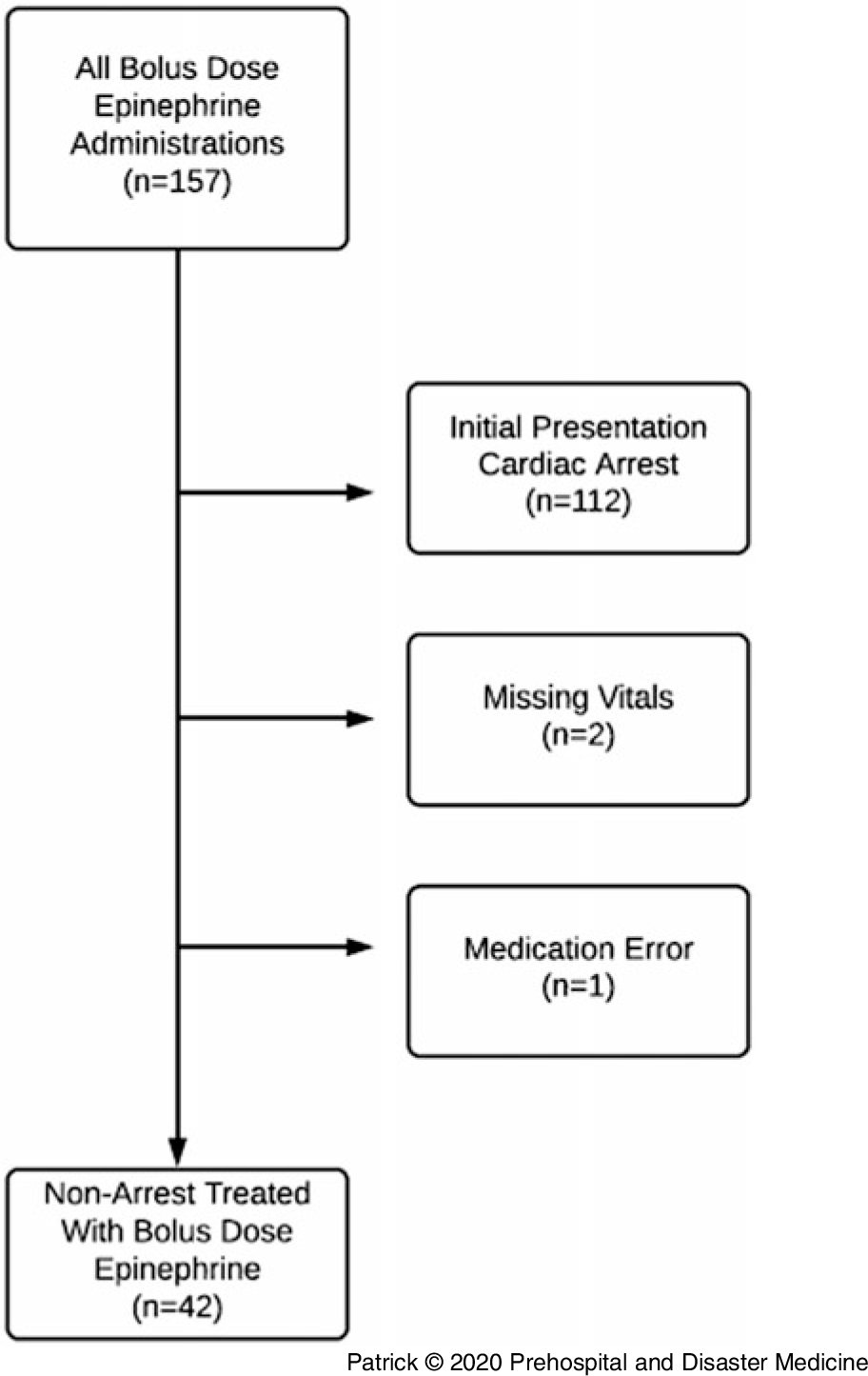

Patient inclusion criteria for initial EMS chart review included all patients who were given bolus dose epinephrine throughout the study period. Then, the patients who were given the treatment post-cardiac arrest were removed in order to assess strictly hypotensive patients not associated with an initial cardiac arrest event, consistent with the objective of the study.

The developed EMS protocol for bolus dose epinephrine used in this study is noted in Figure 1. Paramedics initially identified SBP<90mmHg and then administered 20mcg of epinephrine which could be repeated in two minutes if the SBP remained less than 90mmHg. Crystalloid fluid was also available and encouraged within this protocol. The paramedics were instructed to mix 1mL 1:10,000 epinephrine with 9mL of 0.9% normal saline for a final epinephrine administration concentration of 10mcg/mL.

Figure 1. Push Dose Epinephrine Protocol.

As part of the release of this protocol, 250 paramedics underwent an initial, mandatory two-hour training session that included a review of vasopressor pharmacology, focused didactic instruction on the pathophysiology, and clinical findings in the various types of acute decompensated shock, along with an introduction to specifics of the bolus dose epinephrine treatment protocol (Figure 1). The training sessions occurred approximately one month prior to protocol deployment. This knowledge was then reinforced by two podcasts, produced in-house, which were available and promoted for the duration of the study period. Providers demonstrated an understanding of acute decompensated shock and the vasopressor treatment protocol through both written and psychomotor examinations at the conclusion of the mandatory training session.

Measures

Data were abstracted from the EMS electronic patient care reports (ePCRs) by a two-person expert review panel (one physician and one paramedic) with a standardized data collection form. The study variables included demographic information and hemodynamic data throughout patient transport. Epinephrine routes of administration and dosages given by EMS were compiled from the ePCRs as well. Additional information collected included EMS fluid administration volume and EMS on-scene time and patient transport times. Hemodynamic data such as blood pressure measurements and heart rate during EMS transport were also collected. The vital sign data immediately before and five minutes after epinephrine administration were used in the analysis. Finally, the incidence and type of EMS advanced airway management (defined as endotracheal intubation or supraglottic airway placement), along with the rate of vasopressor continuous drip administration following bolus dose epinephrine, were collected as well.

Analysis

All analyses were completed using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation; Redmond, Washington USA) and Stata IC Version 15.1 (StataCorp LLC; College Station, Texas USA). Descriptive statistics were calculated with median (IQR) presented for continuous variables of frequency (%) presented for categorical variables.

Results

A total of 157 EMS patient charts were identified and reviewed that satisfied the inclusion criteria. From these charts, 112 patients were determined to not qualify for inclusion due to an initial presentation in cardiac arrest (Figure 2). Two patients were excluded due to missing vital sign values and a final patient was excluded due to a medication error. Five patients were hypotensive with SBP <90mmHg and satisfied inclusion criteria, however, these patient’s blood pressure readings just prior to administration of medication increased above SBP 90mmHg. These were included since the intention to treat by protocol was previously established. Forty-two patients were included in the final evaluation.

Figure 2. Patient Exclusion/Inclusion Flowchart.

Of the 42 patients included in the final chart review, these patients had a mean age of 68 years-old, most were white, and had a slight female predominance (Table 1). These were primarily medical patients with 41/42 (98%) receiving bolus dose epinephrine for a medical indication (Table 2). The most common primary patient complaints documented by paramedics were altered mental status in 23/42 (55%) and respiratory failure in 13/42 (31%). Also, the most common indications for bolus dose epinephrine were general hypotension in 17/42 (41%), pre-delayed sequence intubation in 16/42 (38%), and sepsis in 9/42 (21%).

Table 1. Demographics of Patients Receiving Prehospital Push Dose Epinephrine

Table 2. Clinical Characteristics of Patients Receiving Push Dose Epinephrine

Abbreviations: DSI, delayed sequence intubation; ETT, endotracheal tube; PDE, push dose epinephrine.

The median on-scene EMS time for these patients was 32 (21-46) minutes with a median transport time of 16 (10-20) minutes (Table 2). These scene times were slightly longer than the overall EMS median system scene times, which was expected considering the higher than average rate of advanced airway management in this cohort. The transport times, however, were similar to the overall EMS system transport times. Other treatments included a 0.9% normal saline bolus in 40/42 (95%) patients. The median volume of normal saline administered was 600mL (400-1000). This was a critically ill group of patients with 26/42 (62%) of the patients requiring advanced airway management during EMS care and 20/42 (48%) requiring continued vasopressor drip administration after bolus dose epinephrine use (Table 2).

Over three-quarters of patients required only one or two boluses of epinephrine (Table 3). Of the patients treated, 19/42 (45%) received a single 20mcg dose and 13/42 (31%) received a second 20mcg dose (Table 3). The patients primarily received bolus dose epinephrine via IV route as opposed to intraosseous (IO) administration: 34/42 (81%) patients received treatment via IV versus 8/42 (19%) through IO route (Table 3).

Table 3. Dose and Route Information for Push Dose Epinephrine Patients

Abbreviations: IO, intraosseous; IV, intravenous.

Patients treated with IV bolus epinephrine had a median initial EMS SBP of 78mmHg (65-86; Table 4). The median SBP five minutes post-EMS bolus dose epinephrine administration was 93mmHg (75-111). Bolus dose epinephrine patients also had a median initial EMS mean arterial pressure (MAP) of 58mmHg (50-66). The median MAP five minutes post-EMS bolus dose epinephrine administration was 69mmHg (59-83). The median pulse following bolus dose epinephrine was unchanged at 96 (80-116) beats per minute before and 95 (82-113) following treatment (Table 4). Of the patients treated, 36/42 (86%) had an improvement in SBP. One patient had a brief hypertensive episode, which resolved without treatment, during EMS transport following a 20mcg dose of epinephrine. The blood pressure in this specific patient increased from 68/44 pre-treatment to 193/131 following 20mcg of epinephrine. However, the blood pressure then decreased to 120/58 in eight minutes without any additional treatment. The patient was normotensive upon ED arrival and had no arrythmia, chest pain, or other complaints. There were no other reported adverse events during transport.

Table 4. Pre/Post and Change in Vital Signs of Patients Receiving Push Dose Epinephrine

Abbreviations: DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HR, heart rate; MAP, mean arterial pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Discussion

This study is the first ground-based EMS evaluation of the use of bolus dose epinephrine in non-cardiac arrest hypotensive patients. The increase in SBP and MAP demonstrated in this study with initial epinephrine bolus administration during EMS transport are consistent with prior ED and HEMS results.Reference Panchal, Satyanarayan, Bahadir, Hays and Mosier9,Reference Nawrocki, Poremba and Lawner16 This was an acutely unstable patient population with approximately one-half requiring both multiple doses of bolus dose epinephrine along with continuation of a vasopressor drip infusion. Patients also were aggressively fluid resuscitated receiving an average of nearly 750mL 0.9% normal saline during EMS transport. Two-thirds of the patients required advanced airway management as well. As expected, the adverse effect of hypertension after treatment with epinephrine was observed at a rate (2.4%) consistent with that seen in larger studies.Reference Nawrocki, Poremba and Lawner16 The single occurrence of hypertension seen in this study resolved without additional treatment or significant clinical consequences. The results suggest that prehospital administration of bolus dose IV epinephrine may be effective with minimal adverse events and are a first step in evaluating a possible role for bolus dose IV epinephrine in the prehospital setting of non-cardiac arrest associated hypotension.

One concern in this study was whether prehospital providers could correctly administer bolus dose epinephrine without medication errors. Others have brought similar concerns with ED physicians attempting to mix and administer bolus dose vasopressors in the hospital setting as well.Reference Cole18,Reference Holden, Ramich, Timm, Pauze and Lesar19 In this evaluation, a single medication error occurred that was not included in the final evaluation but warrants discussion. Due to epinephrine shortages, EMS medication stock was limited and changed from 1:10,000 to 1:1,000 epinephrine concentration, so the bolus dose concentration given to the patient was 100mcg/mL as opposed to 10mcg/mL. This particular patient had no hypertension, tachycardia, or arrhythmia during transport and arrived at the ED without event. In fact, prior prehospital studies safely used starting doses of 100mcg when utilizing bolus dose epinephrine.Reference Guyette, Martin-Gill, Galli, McQuaid and Elmer17 To prevent additional occurrences of dosing errors, further paramedic education was provided, and the protocol was amended to include instructions on mixing bolus dose epinephrine using the 1:1,000 epinephrine concentration as well. The use of pre-prepared standardized preparations may also improve the safety of prehospital bolus dose vasopressor administration.

The primary motivation for development of this protocol was the need for a rapid, simple, and available method to treat hypotension when managing hemodynamically unstable patients in the austere prehospital environment. Preparation and administration of a vasopressor drip is time consuming and often only possible when inside the ambulance; therefore, bolus dose vasopressors function as a bridge to definitive therapy while on scene. In ED, intensive care unit, and operating room settings, bolus dose IV epinephrine has been shown to be safe and effective in augmenting hypotension.Reference Panchal, Satyanarayan, Bahadir, Hays and Mosier9-Reference Reiter, Roth, Wathen, LaVelle and Ridall13,Reference Rotando, Picard, Delibert, Chase, Jones and Acquisto20-Reference Wang, Shen, Liu, Yang and Xu22 Bolus dose epinephrine has also been studied in the prehospital HEMS and critical care transport settings,Reference Nawrocki, Poremba and Lawner16,Reference Guyette, Martin-Gill, Galli, McQuaid and Elmer17 but this study is the first to evaluate prehospital bolus dose epinephrine for hypotensive patients in a ground-based EMS service. Even transient peri-intubation hypotension is known to increase mortality in the hospital setting,Reference Heffner, Swords, Kline and Jones5 and mortality benefit has been noted with earlier initiation of vasopressor therapy in septic shock patients as well.Reference Dellinger, Levy and Rhodes23,Reference Beck, Chateau and Bryson24 Considering two-thirds of the patients treated with bolus dose epinephrine in this study required advanced airway management and almost one-half were treated pre-delayed sequence intubation, it is possible that larger studies may demonstrate mortality benefits as a result of this aggressive hemodynamic management.

Limitations

This study was limited by its retrospective nature, small sample size, and due to the fact that patients were treated within a single ground-based EMS agency. Further, small sample size limited the ability to study the effects of bolus dose epinephrine on both safety and prehospital morbidity and mortality. Randomized studies with larger sample sizes are needed to further investigate the effects of prehospital bolus dose epinephrine on patient morbidity and mortality in EMS patients with hypotension.

Conclusion

This study is the first ground-based EMS prehospital evaluation of the use of bolus dose IV epinephrine for hypotension in non-cardiac arrest patients. Under this prehospital protocol, SBP was successfully augmented with minimal adverse events and no deaths or arrhythmia during transport. Future work must be directed at evaluating the safety and possible mortality benefits from prehospital bolus dose epinephrine administration.

Conflicts of interest

No conflicts of interest to report.